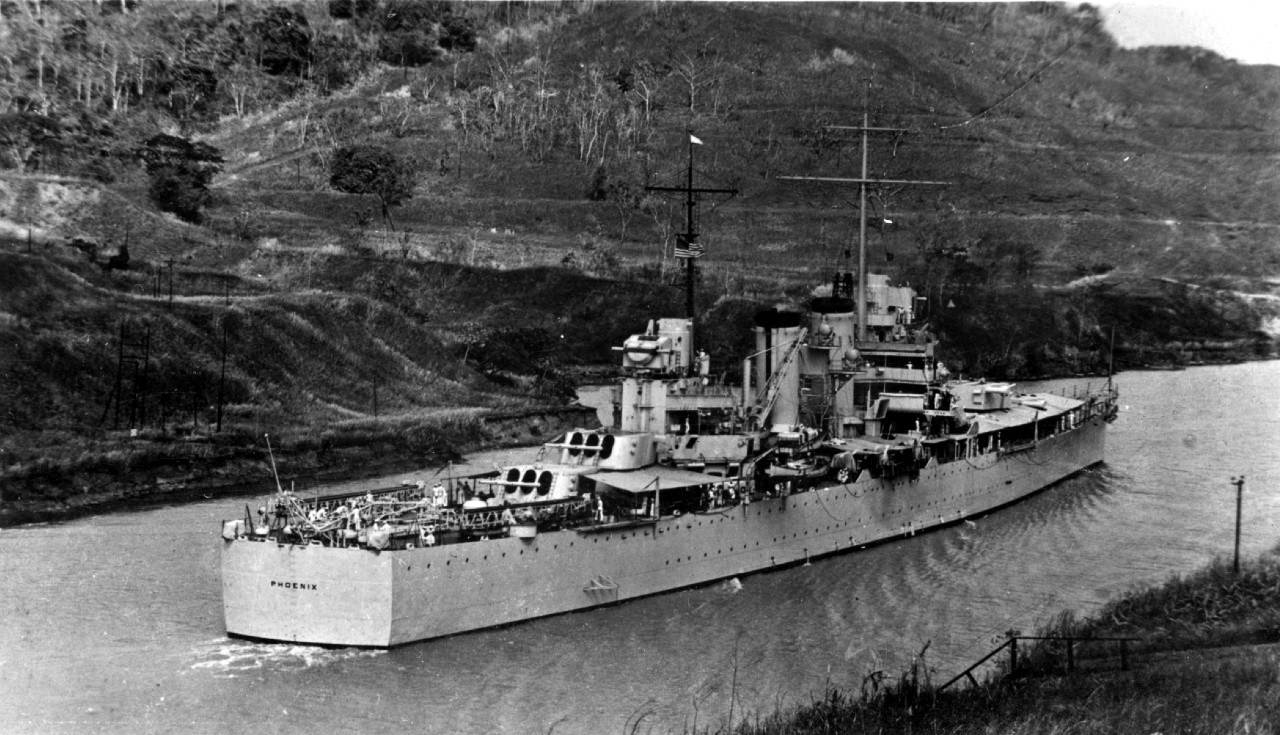

Phoenix III (CL-46)

1938–1946

The first and second U.S. Navy ships named Phoenix were named for a mythical bird of ancient Egypt which, after living some 500 years, consumes itself in fire, only to rise again rejuvenated from its ashes. The third, fourth, and fifth Phoenixes were named for the capital of Arizona located on the Salt River.

III

(CL-46: displacement 10,000; length 608'4"; beam 61'9"; draft 19'5" (mean); speed 33.6 knots; complement 868; armament 15 6-inch, 8 5-inch, 8 .50 cal. machine guns; aircraft 4 Curtiss SOC-1 Seagulls; class Brooklyn)

An Act of Congress authorized CL-46 on 13 February 1929; the Navy awarded the contract for CL-46 to the New York Shipbuilding Co., on 3 October 1934; and the following day Secretary of the Navy Claude A. Swanson selected the name Phoenix for her. The third Phoenix was laid down on 15 April 1935, at Camden, N.J.; launched on 12 March 1938; sponsored by Mrs. Dorothea K. Moonan (née Kays), daughter of Cmdr. Harlow T. Kays (Ret.) of Arizona; and commissioned at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pa., on 3 October 1938, Capt. John W. Rankin in command.

The nine original Brooklyn (CL-40) class light cruisers also comprised Boise (CL-47), Helena (CL-50), Honolulu (CL-48), Philadelphia (CL-41), Nashville (CL-43), St. Louis (CL-49), and Savannah (CL-42). Helena and St. Louis underwent modifications while they were being built and are often considered the separate St. Louis class. The to them changes included twin 5-inch guns and new higher pressure boilers arranged differently than their predecessors, so that the ships could survive a single hit to their engineering spaces that might otherwise render them dead in the water.

Designed and built under the terms of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, the Brooklyn class cruisers displaced less than 10,000 tons and were armed with 6-inch guns as their main battery. The ships were designed largely as a response to heavily-armed Japanese cruisers, however, and as a result, mounted their 6-inch guns in five triple turrets, three forward and two aft, with Turrets II and IV in super-firing (mounted above Turrets I and III) position. The class was also designed with a flush-deck hull, with a high transom and a built-in aircraft hangar aft.

Phoenix initially embarked four Curtiss SOC-1 Seagulls of Cruiser Scouting Squadron (VCS) 8 as her Aviation Unit. The new cruiser set out on her shakedown cruise to Port of Spain, Trinidad; Santos, Brazil; Buenos Aires, Argentina; Montevideo, Uruguay; and San Juan, P.R. Phoenix returned to Philadelphia in January 1939. By June of that year, Phoenix routinely embarked four Naval Aircraft Factory SON-1 Seagulls of VCS-9, the squadron led by Lt. Cmdr. Horace B. Butterfield.

Phoenix developed an aircraft cross-catapult launch in 1940. The system enabled her to launch up to four planes in about six minutes without requiring the ship to change direction. The bottom of the Seagulls’ floats cleared the top of the other catapult by about a foot.

Brooklyn held the Light Cruiser 5ʺ/25 Caliber Armament Broadside Gunnery School (17–21 June and 29 June–3 August 1940). At times, the ship hosted gun crews from Boise, Honolulu, Nashville, Philadelphia, Phoenix, and Savannah, as well as from aircraft carriers Enterprise (CV-6), Lexington (CV-2), Saratoga (CV-3), and Yorktown (CV-5).

“It is considered that this school was well planned and efficiently conducted,” Rear Adm. Husband E. Kimmel, Commander, Cruisers, Battle Force, United States Fleet, reported to Adm. Stark on 19 August 1940. “The results of this school are very gratifying.” Kimmel elaborated that the surface firings scored about 22% hits, and during the last two firing weeks the 5-inch guns consistently struck the target sleeves in all forms of practices, except ominously in Antiaircraft Battle Practice G, “against which form of attack (glide bombing) the 5-inch/25 battery was relatively ineffective.” The machine guns shot well, however, and splashed a radio controlled target drone in flames, apparently with a punctured gas tank, on its first run. The event also marked the first time that those guns shot down a drone flying at an altitude above 10,000 feet. The students tracked the drone at a mean altitude of 12,300 feet and a true speed of 122 knots, and their shooting hit the target at a position angle of 50°, and it caught fire and crashed.

In addition, Phoenix took part in the Light Cruiser 6-inch/47 Caliber Main Battery Gunnery School (28 May–29 June and 4–26 August 1940). The school’s curriculum was written to instruct gun crews in Brooklyn and St. Louis class cruisers in the “fundamental principles of main battery gunnery” and “to develop the maximum effectiveness of main battery fire”. The school furthermore aimed to determine the desirability of employing a “rate officer” similar to the tradition in the British Royal Navy.

Starting with four Local Control Battle Practices, the firing program included (in order): Day Battle Practice (fired by Phoenix); Night Battle Practices (flank illumination) (St. Louis); Day Battle Practice (St. Louis); Advanced Day Battle Practices (Phoenix); and Night Battle Practices (Phoenix). The instructors explained the acceptable control methods to the students and then permitted them to develop their own procedures for Local Control Battle Practice, noting that their decision raised a “high degree of interest” throughout the exercises.

The evaluators determined a number of conclusions including: stereo spotting was possible at ranges under 12,000 yards; a rate officer equipped with 7x50 binoculars in an aloft observing station did not prove as effective as the spotters in observing target course and speed changes; flank illumination seemed more successful than own ship’s searchlight illumination and they recommended to pursue that tactic whenever possible; and the plot needed to follow the spotter’s estimate of target angles more closely.

Nonetheless, the gun crews made some errors including: under-spotting by failing to cross the target; developing the incorrect rate for range keeping though failing to consider both range and bearing components of the solution; and illumination and control of fire at night by waiting for the rangefinder range before opening fire, after the illuminating ship had opened its searchlights on the target. Phoenix wrapped up the first phase of her gunnery practice in preparation for a voyage and lay to at Lāhainā Roads, a roadstead between Maui, Lāna‘i, Moloka‘I, and Kaho‘olawe, T.H., that the Navy often used as an anchorage. The school temporarily shifted to St. Louis in her absence.

From there she set out on the first leg of a goodwill cruise to the Pacific coast of South America (20 June–7 August 1940). In addition to the normal preparations for such a lengthy cruise, Capt. Herman E. Fischer, the commanding officer, requested $500 “for entertainment purposes under Contingent Navy” from Adm. James O. Richardson, Commander-in-Chief, United States Fleet, and Richardson granted the request. Fischer also foresightedly sent a dispatch to Adm. Harold R. Stark, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), requesting the latest Foreign Service List, Who’s Who, and “other appropriate information”, and that Stark arrange for the information to be sent via airmail to Balboa in the Panama Canal Zone, where the ship intended to stop on her voyage.

Fischer sent a dispatch to Cmdr. Walter W. Webb, the U.S. Naval Attaché to Chile, on 24 June 1940, in order to give him as much time as possible prior to the ship’s scheduled arrival, suggesting times for exchanging calls, tentative arrangements for the commanding officer’s luncheon and ship’s reception on board, docking arrangements, and the maximum number of officers available for any one occasion. The captain amplified the dispatch by a second letter he ordered sent via airmail through Balboa. In the meanwhile, on the 26th, Stark informed Fischer that “diplomatic arrangements had been completed for informal visits to the aforementioned ports”.

Phoenix turned her prow southward at 0900 on 20 June 1940. During her passage the ship’s company organized committees to address the expected activities that could arise during their port visits. The light cruiser celebrated Independence Day and refueled and provisioned while at Balboa (2–5 July), and then resumed her voyage. The cruiser put in to Valparaiso, Chile, for a six-day visit (12–18 July) to “cultivate friendly relations”. Phoenix fired the national salute to Chile when she reached a point about one and one half miles from Point Angeles light at 0853 on the 12th. A few minutes later 0908, she followed with a 17-gun salute to Vice Adm. Julio P. Allard, Commander-in-Chief of the Armada de Chile [Chilean Navy]. Allard also held the temporary title of the Intendente [governor] of the province during the ship’s stay. Chilean guns at the Naval School Barracks and in the vicinity of Fort Buras returned both salutes. Cmdr. Webb and the port’s pilot boarded the ship about a half mile from the breakwater, and she then continued inbound and moored stern to the mooring jetty.

Fischer and Webb called on Allard, as well as Col. Frederico Japke, Commander-in-Chief of the Garrison, Cristóbal Sáenz C., Minister of Foreign Relations, and Alfredo Duhalde V., Minister of National Defense, and to Claude G. Bowers, U.S. Ambassador to Chile, and Renwick S. McNeice, the American Consul at Valparaiso. Rear Adm. Louis A. Muñoz V, who commanded the local naval station, fell ill just before the ship’s visit and was not available while he recovered. Allard welcomed the ship’s officers at a cocktail party held at that country’s Naval Club, and Phoenix returned the hospitality with a reception on board. The guests who attended the commanding officer’s luncheon in honor of Allard given on board the vessel included Lt. Col. Ralph H. Wooten, USA, the U.S. Military Attaché.

The ship reached Chile during the winter in the southern hemisphere and foul weather plagued the visit. A storm had damaged shipping in Valparaiso harbor in May 1940, blown loose battleship Almirante Latorre from her anchorage, and overturned a 4,000-ton merchantman in a dry dock. The visitors and their hosts accordingly made a number of precautions, which included placing a pilot at the disposal of the cruiser. The action proved prudent when a storm swept through the port on the night of 12 and 13 July 1940. The winds increased until they reached an average velocity of 24 knots, with gusts at frequent intervals from 35 to 45 knots. The sea broke over the landing and rendered boating dangerous, and all small craft took shelter in the small inlet by the landing area, which thus became congested. The pilot stayed on board Phoenix overnight, and the ship kept steam up in the throttles with the intention of being able to sortie within 15 minutes if necessary, but otherwise rode out the storm undamaged. Another tempest struck the area on the 17th with high winds of 18–22 knots and heavy swells.

The warship held her reception from 1530–1730 on the 17th. Phoenix, Bowers, McNeice, and the Chilean Navy sent 500 invitations for the soirée, only about half of whom attended because of communist demonstrations ashore and the worsening weather conditions. Phoenix moored away from the dock and the boats shuffled the guests back and forth. The ship’s company rigged awnings and side curtains on the forecastle, and served sandwiches, salad, ice cream, and punch. The orchestra played during the reception and guests danced on the forward part of the ship. In addition, the crew opened the second deck for inspection and provided coffee in the wardroom, which “was very much in demand by the Chileans”.

In addition to the communist demonstrators, tensions ran high as a result of Axis influence in the country. Thousands of Germans and Italians lived in Chile, and numbers of native Chileans traced their descent from German or Italian immigrants. German and Italian schools and newspapers served some of these communities, and a German Chilean youth organization existed. In some instances, members of these communities espoused Nazi or Fascist Italian ideologies, and the Allies feared that enemy agents and spies infiltrated these communities and operated among them. Allied fears proved justified as the war continued and they uncovered evidence of Operation Bolívar—German espionage in Latin America.

By 1944, the Department of State believed that German and Japanese agents in neutral countries were intensifying their efforts to obtain Allied information. The department instructed posts to review their security measures, and to investigate the associations of all post staff “down to the lowliest members.” Shortly thereafter, the U.S. Vice Consul in Arica, Chile, discovered that his 17-year-old janitor had been selling the Consulate’s trash to the local chief of Investigaciones (Chile’s counterpart to the FBI), a man known to have contacts with Axis agents. One document in the trash identified U.S. Navy codes but did not contain enough information to permit decoding of messages. The Consulate promptly fired the janitor, and later learned that the chief probably gave the documents to his superiors in order to improve his chances for promotion, rather than passing them to Axis agents. The ship’s visit helped to emphasize U.S. support for a democratically elected Chilean government and opposition to the Axis.

Fischer, Webb, a lieutenant commander and a lieutenant from Phoenix meanwhile (14–15 July 1940) accompanied a Chilean naval aide on a train from Valparaiso to Santiago. The party stayed at the Hotel Crillon, and on several occasions and in different locations including the U.S. Embassy dined with diplomatic officials, high ranking Chilean officers, and Americans of prominence. Pisco, a local brandy favored by the American community, also became a popular choice with the ship’s company.

Upon the party’s return to the ship they continued their round of state functions. On the 16th, Fischer laid a wreath at the Heroes of Iquique Monument for Capt. Agustín A. Prat Chacón (3 April 1848–21 May 1878), a Chilean naval hero who was killed at the Battle of Iquique in the War of the Pacific. Phoenix landed a platoon of bluejackets and a platoon of marines for the ceremony, which drew a crowd of nearly 3,000 people. The ship’s orchestra and a Chilean naval band played their respective country’s national anthems, and the sailors and marines then passed in review. “This ceremony was very impressive,” Fischer reported, “and gratefully received by the Chilean Naval officials and the general public.” The ship’s basketball team also played the Chilean Naval Academy’s team on an outside clay court, a game the Chileans won 44 to 20.

The cruiser’s four Seagulls flew ashore to their host’s naval air station at Quintero on 17 July 1940. The naval aviators observed that their counterparts seemed “well acquainted with aviation matters,” though seemed understandably reticent to show their guests too much of the station, which consisted of a large operating hangar, a repair hangar, a storehouse, and a machine shop. The Americans noted limited repair and maintenance facilities, which they described as in “very poor condition,” though adding that “the hangars were large and in fair shape”. The visitors examined a Dornier Do J Wal undergoing repairs after the flying boat made a forced landing in a field short of the station, a trio of Arado Ar 95 reconnaissance and patrol biplanes, one on floats and the other pair on wheels, another couple of Dorniers, and a few light aero club sport planes that Chilean naval officers flew. The foul weather later that day precluded additional inspections, and the wash would have prevented any planes beaching on the small sandy beach north of the air station.

“The Phoenix,” Fischer signaled Allard upon the ship’s departure, “sends sincere expressions of deepest appreciation for the hearty welcome reception and many kindnesses accorded us.”

Allard and the officers of the Armada de Chile responded by extending “their affectionate Godspeed” and “a good voyage” to their “true comrades”.

From there the ship steamed northward and visited to Callao, Peru (22–26 July 1940). On the 25th, the snatch block on a mooring line carried away and the flaying line struck S1c Vernon Le Roy Harrington and threw him against a turret. Harrington died from his injuries, which included a simple fracture to his skull (the left parietal) and a traumatic rupture to a lung. The tragedy marred the ship’s visit but she concluded her goodwill cruise to Peruvian and Chilean waters and charted a course for home. Phoenix refueled at Balboa on 30 July, and rejoined the fleet at San Pedro, Calif. From there she returned to the gunnery school, which shifted back from St. Louis, and completed the second phase of exercises. By November of that year, she embarked an operational average of four SOC-3s of VCS-9, Lt. Cmdr. Clarence E. Ekstrom.

The Allies in the meantime reinforced their Pacific bastions as war clouds loomed in the face of increasing Japanese aggression. The Americans dispatched one such convoy of soldiers on board Army transport Hugh L. Scott to the Philippines (28 August–16 September 1941), and planners debated the security of routing the ship through the Gilbert Islands [Kiribati], Torres Strait, and then northward through the Netherlands East Indies [Indonesia]. The vessel’s passage would thus likely have taken her beyond the range of Japanese air strikes in the event of war, and the planners considered sending the transport without escorts. As the Americans weighted their options, however, they considered deploying escorts from the Asiatic Fleet, and finally shelved those plans altogether and decided instead to direct Hugh L. Scott to chart a direct course across the Central Pacific through the Mariana Islands. German auxiliary cruiser Komet, Kapitän zur See Robert Eyssen in command, had just raided Allied ships and bastions in the Pacific, and in the unlikely prospect that she or another German raider attacked Hugh L. Scott, the Navy decided to assign a close escort to her from Hawaiian waters.

Hugh L. Scott set out from San Francisco but many of the soldiers she embarked struggled with seasickness before she reached Honolulu, Oahu, T.H., on 2 September 1941. The transport disembarked some of her passengers and brought others on board, and the ship, carrying a mix of about 1,100 men from the mainland and the islands including elements of the 1st Battalion, 200th Coast Artillery, 14th Bomb Squadron (ground echelon), and replacements, resumed her westward journey that evening. On the 4th, Phoenix joined her and took station 1,000 yards of Hugh L. Scott’s starboard quarter, and the pair continued their voyage as Task Force (TF) 14. Phoenix and her charge passed through San Bernardino Strait and concluded their journey when they moored to Pier 7 at Manila.

Heavy cruiser Astoria (CA-34) operated as TF 17 as she escorted a second convoy, consisting of oiler Guadalupe (AO-32) and Army transport President Coolidge, from San Francisco via Oahu and the Marianas to the Philippines (8–26 September 1941). The two ships carried approximately 2,000 men including some of the 1st Battalion, 200th Coast Artillery, 54 M-3 light tanks of the 194th Light Tank Battalion, and the 17th Ordnance Company. In addition, Guadalupe carried six motor torpedo (PT) boats of Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron (MTBRon) 3, Lt. (j.g.) John D. Bulkeley, as deck cargo. Guadalupe spent several days unloading fuel and then set out for her return voyage. Phoenix rendezvoused with Guadalupe in San Bernardino Strait and screened the ship back to Pearl Harbor.

Upon her return to Hawaiian waters, Phoenix operated administratively under Rear Adm. H. Fairfax Leary, Commander, CruDiv 9, who served double-hatted as Commander Cruisers, Battle Force. Boise, Helena, Honolulu, and St. Louis comprised the other ships of the division, and VCS-9, Lt. Cmdr. Benjamin B.C. Lovett, provided their aircraft. Four of the squadron’s SOC-3s usually operated from Phoenix.

As the sun rose on 7 December 1941, Phoenix lay in berth C-6 northeast of Ford Island, not far from hospital ship Solace (AH-5), which lay astern of the cruiser. Phoenix’s men were moving unhurriedly in their peacetime Sunday morning routine, and some prepared for quarters and colors, while others finished eating or writing letters. The ship’s Turret III was out of commission due to a swollen 6-inch gun barrel. Unbeknownst to the ship’s company, however, Japanese Dai-ichi Kidō Butai (the 1st Mobile Striking Force), Vice Adm. Nagumo Chūichi in command, sailed from Japanese waters and attacked Oahu.

Observers on board Phoenix’s signal bridge sighted strange planes coming in low from north of Ford Island at about 0755. Men observed that one of the aircraft, bearing the rising sun of Japan, swooped over the stern of Raleigh (CL-7), moored off Ford Island to Phoenix’s port quarter, fired all its guns, and flew toward the Ford Island Central Tower and dropped a bomb. Additional Japanese planes thrust toward the battleships moored at Battleship Row, along the south side of Ford Island.

At 0806 Phoenix signaled the other ships in Sector Four to “prepare to get underway”. Gunfire splashed an attacker at the end of the pipe line astern of berth F-8 at 0807, and the plane burned in the water. Phoenix’s men rushed to man their battle stations and her machine gun battery began shooting at the Japanese aircraft three minutes later, followed five minutes after that by the antiaircraft battery. A group of three planes, which observers believed to be Aichi D3A1 Type 99 carrier bombers, approached from the northeast and attacked Phoenix, a nest of destroyers at berth X-11, and destroyer tender Whitney (AD-4) and some of the ships nested with her—Case (DD-370), Conyngham (DD-371), Reid (DD-369), Selfridge (DD-357), and Tucker (DD-374). Phoenix escaped damage and continued the fray. Shortly after the attack began, Ens. Warren H. Sears, USNR, a turret officer on board West Virginia (BB-48), boarded a boat at the navy yard that took him over to Phoenix instead of Battleship Row at Ford Island, and Sears joined the ship’s company in fighting the ship.

The ship’s engineering sailors worked furiously to get Phoenix ready for sea and at 0845 they reported that she could get underway to escape the carnage. A formation of 11 enemy planes crossed over the fleet at high altitude, which the ship’s spotters estimated at 10,000 feet, on a heading of 070°, 15 minutes later. Phoenix fired 50 5-inch rounds at the aircraft but missed. A second wave of planes roared in at about 0900. Some of the Japanese aircraft dived at about a 30° angle on the ships berthed along the northern side of Ford Island, and Phoenix blasted both her antiaircraft and machine gun batteries at them, firing about 20 5-inch shells. A destroyer’s guns disintegrated one of the enemy planes.

Additional planes attacked the battleships at 0910 and Phoenix swung her guns around to help the battlewagons. The ship shot approximately 60 more 5-inch rounds at the attackers, apparently without effect. After some of the planes pulled out of their dives they turned toward berth C-6 and the ship’s machine guns fired at them. Phoenix also shot periodically at planes that attacked the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard and the vessels there.

Phoenix began to stand down the North Channel at 1010, but received orders not to sortie and returned to her moorings. The ship undauntedly made again for the open sea and again received orders, this time via Tennessee (BB-43)—“From Cincpac [Kimmel] do not sortie”. Phoenix obediently turned around in the channel and started back to berth C-6. Rear Adm. Leary ordered the ship to sortie and she finally did so at 1115, steaming down the South Channel toward the sea. Capt. Fischer did not require an additional turret officer, so as Phoenix passed West Virginia, Ens. Sears dived overboard and swam to the burning battleship.

Fischer reported to Kimmel that although Phoenix joined other ships in firing at three planes, he could not accurately determine if the cruiser damaged any of the attackers. Phoenix fired 353 5-inch, 35 3-inch, and 4,500 .50 cal. rounds during the battle.

Phoenix escaped the disaster unharmed and cleared the channel and began zig zagging at high speed. At half past noon Phoenix joined some other ships that sortied from Pearl Harbor including Detroit (CL-8), St. Louis, and several destroyers and fast minesweepers and they operated as TF 1. Earlier that morning TF 3, Rear Adm. Milo F. Draemel, Commander Destroyers, Battle Force, and Destroyer Flotilla 2, comprising Minneapolis (CA-36), Capt. Frank J. Lowry, and four destroyer minesweepers of Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 4, had begun routine maneuvering southwest of Oahu. During the afternoon watch Kimmel ordered TF 1 to rendezvous with TF 3, and they combined under Draemel in an impromptu task force. Minneapolis initially launched some of her four SOC-1s of VCS-6 that searched about 150 miles out from the ship, along an arc of 150° to 180°.

TF 8, Vice Adm. William F. Halsey Jr., in command and formed around Enterprise, had just delivered 12 Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats of Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 211, Maj. Paul A. Putnam, USMC, to Wake Island. On that fateful day Enterprise was returning to Pearl Harbor and reached a position about 200 miles to the westward of Oahu as the Japanese attack unfolded.

A report claimed to sight some of the enemy ships south of the island, and toward dusk -- just before 1700 -- Enterprise launched a strike consisting of her 18 operational Douglas TBD-1 Devastators of Torpedo Squadron 6, a half dozen Douglas SBD Dauntlesses fitted with smoke generators to screen the torpedo bombers with smoke, and six escorting Wildcats. The planes searched out to about 100 miles southeast of Enterprise but failed to sight any enemy ships, and then the bombers returned to the carrier and the Wildcats ashore. Halsey directed Draemel to search to the southward of Oahu, until another report claimed to sight them to the northward, and Phoenix and other ships searched for the enemy carriers in an area about 100 miles north of Oahu. The Japanese eluded discovery, however, as Nagumo brought his ships about and sailed from Hawaiian waters.

The following day on 8 December 1941, TF 1 worked with TF 8 but Enterprise ran low on fuel and she detached from the formation that afternoon. Six Wildcats flew protectively overhead as she entered Pearl Harbor as the sun set, and after refueling and taking on provisions, the carrier stood back to sea during the morning watch on 9 December. The two task forces rendezvoused at 1235 and until 1705 patrolled the area, when Minneapolis, Detroit, Phoenix, and St. Louis detached and returned to Pearl Harbor. The ships slid back into the harbor through water covered by oil from the sunken ships, and while sailors attempted to rescue men trapped in vessels that capsized during the attack. The air reeked of death and oil, and fires still burned from the stricken ships and ashore, casting an eerie glow over the men. Following her ordeal, Phoenix returned to the west coast and lay briefly at Mare Island Navy Yard, Calif.

The enemy attack caught the Americans in the midst of building up their forces in the Hawaiian Islands, and the Japanese onslaught lent a degree of urgency to their endeavors. In particular, the garrison required additional planes to replace the ones destroyed or damaged by the Japanese, and fighters topped the list. One such contingent consisted of 2,191 men, primarily soldiers but with a handful of sailors, the soldiers from part of the Army’s 161st Infantry Regiment and the 2nd Battalion of the 57th Coast Artillery Regiment. The cargo included 54 Curtiss P-40E Warhawks, two Douglas C-53 Skytroopers, 33 10 5-millimeter howitzers, 28 155-millimeter guns, nine 37-millimeter antitank guns, machine guns, bombs, artillery shells, small arms ammunition, naval supplies, fuel oil, and gasoline.

The reinforcements set out in store ship Aldebaran (AF-10), transport Harris (AP-8), and Army transports President Garfield and Tasker H. Bliss. Phoenix, Cushing (DD-376), and Perkins (DD-377) comprised their escort as Task Group (TG) 15.7 as the ships formed up as Convoy No. 2004. Phoenix fueled and provisioned while moored at Mare Island on 16 December 1941, and installed a new 5-inch gun barrel in her No. 3 gun. She shifted berths and anchored at C-3 in San Francisco at 1757, and at 0630 the following day proceeded out of San Francisco Bay with the convoy. Humphreys (DD-236) acted as a coastal escort, and Harris, Crane (DD-109), Crosby (DD-164), and Kilty (DD-137), along with Platte (AO-24) and Sabine (AO-25), joined the convoy during the morning watch on the 18th. Humphreys, Crane, Crosby, and Kilty steamed with the convoy only briefly (0830–1145) but then all four detached. The cruiser launched her planes daily, weather permitting, for search and antisubmarine patrols, but the convoy continued without incident. Five utility aircraft flew out from Oahu and covered the ships to the off-shore patrol area as they reached Pearl Harbor on Christmas Eve 1941.

Phoenix did not enjoy the holidays for long, however, because she helped escort the return convoy as they evacuated people from the Hawaiian Islands to San Francisco (30 December 1941–6 January 1942). Again acting as the flagship of TG 15.7, the cruiser set out in company with Aylwin (DD-355) and Perkins to shepherd Harris, President Garfield, Tasker H. Bliss, and cargo ship Procyon (AK-19). Light minelayers Gamble (DM-15) and Montgomery (DM-17) screened the ships as they moved through Hawaiian coastal waters.

The Americans continued to reinforce their forces across the Pacific Rim, and after a month of convoy duty between the United States and the Hawaiian Islands, Phoenix departed San Francisco as the Escort Commander for Convoy No. 2013 bound for Brisbane, Australia (12 January–2 February 1942). The large convoy carried nearly 7,000 men: 51 P-40Es; 19 Bell P-39D Airacobras; 200 tons of aircraft parts; 20 tons of Prestone ethylene glycol; the Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron of the 35th Pursuit Group; elements of the 7th, 8th, and 9th Pursuit Squadrons of the 39th Pursuit Group; 16th and 25th Pursuit Squadrons of the 51st Pursuit Group; 808th Engineer Battalion (Aviation); 4th Air Depot Group; 45th and 51st Airbase Group Headquarters; 686th, 688th, and 693rd Ordnance Companies (Pursuit); 711th and 729th Ordnance Companies (Airbase); 43rd, 54th, and 59th Matérial Squadrons; and the “Remember Pearl Harbor” detachment.

Army transports President Coolidge (21,936 tons) and Mariposa (18,017 tons) carried most of the soldiers and their equipment, and President Monroe, a C3-P&C [passenger and cargo] vessel built for American President Lines but acquired by the War Shipping Administration on a bareboat charter for outfitting for war service, joined the convoy for part of the voyage. President Coolidge required work on a vibration problem in one of her shafts in a dry dock before she sailed. As no regular naval officer was attached to the convoy, the master of President Coolidge served as the Convoy Commander. Navy Armed Guard crews manned President Monroe’s guns, but President Coolidge and Mariposa disembarked their naval gunners prior to the voyage and replaced them with Army gun crews.

Phoenix, Aylwin, and Perkins formed TG 15.9 and escorted Convoy No. 2013 as the ships turned their prows from the Bay Area to seaward at 1608 on 12 January 1942. The convoy steamed in a diamond formation, with President Coolidge as the guide, Mariposa 1,000 yards of President Coolidge’s starboard quarter, Phoenix astern, and President Monroe 1,000 yards on President Coolidge’s port quarter. The following morning Fischer observed that the convoy was proceeding at a speed of about 17 ½ knots and spread out over the ocean. In answer to his inquiries, President Monroe informed him that she could only make 17 knots and a result, threw the convoy out of position. Phoenix repeatedly signaled President Coolidge but she failed to respond, so during the forenoon watch an exasperated Fischer took over the duties of the Convoy Commander and they switched stations.

Upon investigation he discovered that F.T.P. 189 (which contained instructions to U.S. flag convoys) had not been issued to President Coolidge and Mariposa, and C.S.P. 950 Auxiliary Signal Book had never been issued to all three of the vessels in the convoy, although they did have copies of the zig-zag diagrams. Since Aylwin and Perkins were scheduled to come about at midnight, that afternoon Fischer ordered them to deliver their copies of F.T.P. 189 to Mariposa and President Coolidge. The destroyers raced in at 16.5 knots and Fischer observed that they “expeditiously” transferred their copies. The opening of the formation would have rendered the convoy temporarily vulnerable if a Japanese submarine had attempted to slip past the screen.

At midnight Fischer released their coastal escort and the ships continued their journey. President Monroe developed engine trouble on the night of the 17th and the convoy temporarily slowed to 12 knots while she struggled to troubleshoot the problem and regain her station. The ship broke down again the following day, and dangerously delayed the vessels for a second time as she accomplished repairs. On the 19th it was Mariposa’s turn when the ship experienced a faulty telemeter system, and after she regained station for the second time, Fischer directed President Coolidge and Mariposa to switch stations, placing the latter in the stern of the formation in an apparently safer position. About half way through the voyage on the 24th, the Allies shifted most of the convoy’s destination to Melbourne. Three mornings later, New Zealand light cruiser Achilles (70) rendezvoused with the convoy, and accompanied President Monroe as she detached and steamed to the Fiji Islands. As the pair sailed off Achilles signaled Phoenix:

“Congratulations on news from Macassar to-day”—a reference to the Battle of Makassar Strait, where the Allies counterattacked Japanese forces invading the Netherlands East Indies.

The three remaining ships of the convoy changed their formation into open order, with Phoenix in the van, followed by President Coolidge and Mariposa. President Monroe meanwhile reached the Fiji Islands on the 29th and unloaded her troops -- 660 men of the 51st Pursuit Group -- at Suva to augment the Allied garrison there. That day an Allied squadron led by Rear Adm. John G. Crace, RN, and comprising Australian heavy cruiser Australia (D.84), Australian light cruisers Perth (D.29) and Adelaide, and New Zealand light cruiser Leander (75), rendezvoused with the convoy. “Am delighted to welcome you to this area,” Crace signaled Fischer. The ships maneuvered with the convoy for a while, and then the admiral came about but detached Adelaide and she operated under Fischer’s orders. Adelaide knew her home waters well and took station ahead of Phoenix at sunset on the last day of the month. The following morning she led them into Melbourne and at 1745 on 1 February Phoenix moored port side to Nelson Pier at Williamstown in the Port of Melbourne. The ship shifted her berth to Princess Pier two days later. After they unloaded their troops and cargoes, Mariposa steamed to Brisbane and President Coolidge to Wellington, New Zealand.

In the interim Allied planners debated how to shore up the rapidly fragmenting defenses of the Malay Barrier and the Netherlands East Indies. Early in 1942 they had established the American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Command, led by British Gen. Sir Archibald P. Wavell, to defend the region. Hitherto they had used Australia in a limited capacity as a staging point for reinforcements, especially of aircraft, to the ABDA area and India. The Japanese swept through the ABDA area, however, and the Allied troops fighting for that region desperately needed air support. The Allies thus planned Convoy MS-5 to carry fighter planes to Java or to expand the burgeoning U.S. Tenth Air Force in India.

The convoy comprised 2,953 troops from No. 2013 and additional transits: 69 P-40Es; equipment, jeeps, and stores; the Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron of the 7th Bomb Group; 9th Bomb Squadron; Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, 35th Intercept Control Squadron; 51st Pursuit Group; 88th Reconnaissance Squadron; 45th and 41st Airbase Groups; and the 36th Signal Platoon.

Seaplane tender Langley (AV-3), the Navy’s first aircraft carrier (ex-CV-1); cargo ship Sea Witch (6,021 tons) and Army transport Willard A. Holbrook (14,812 tons) were to primarily carry the men and cargoes. The Allies originally intended that Mariposa should also accompany the convoy, but they shifted her to other duties and a pair of Australian troop ships, Duntroon (10,346 tons) and Katoomba (9,424 tons), took her place. Langley ferried 32 of the Warhawks, while Sea Witch carried 27 more crated, and Willard A. Holbrook another ten planes. The Army asked the Navy to allow Phoenix to continue her escort services and shepherd the convoy around Australia, and the Navy initially rejected the request but then acquiesced. Throughout the burst of activity, the Allies also notified Dutch Adm. Conrad E.L. Helfrich, RNN, Commander, ABDA Naval Forces, that Phoenix might reinforce the admiral to help defend Java.

Convoy MS-5, Cmdr. Frederick L. Cavaye, RN, who broke his flag in Willard A. Holbrook, set out from Melbourne on 13 February 1942. After clearing Lonsdale Light the convoy intended to form column, but the flagship did not join them until the following morning. Katoomba burned coal and smoked continually, and Fischer also observed that “she was a poor station keeper.” Five days out some Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Lockheed Hudson Is patrolled over the convoy whenever the ships steamed within range. The vessels rounded the southern end of the continent, and put in to Fremantle, Western Australia, where Phoenix moored to a dock at Shed H at 1203. Langley stood in shortly thereafter and at 1402 moored to that dock astern of Phoenix. 1st Lt. Boyd D. Wagner, USAAF, led the 13th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional) as the men assembled their Warhawks and flew them across Australia to meet Langley, which loaded them.

The convoy captains and masters attended a sailing conference at Fremantle on 21 February 1942. The men discussed their orders to steam to Bombay [Mumbai], India, however, time was of the essence and Helfrich requested immediate reinforcements. During the conference they thus learned that the admiral cancelled the convoy’s sailing orders, and ordered Langley and Sea Witch to detach and proceed independently at best speed for Tjilatjap [Cilacap] on southern Java in the Netherlands East Indies. Japanese bombing and their rapid advance left Tjilatjap as the only viable option for unloading aircraft, though the port lacked the facilities to properly handle the planes.

The convoy returned to sea on 22 February 1942, and charted a course for Colombo, Ceylon [Sri Lanka], from where they were to continue to Bombay. During the evening twilight lookouts sighted British refrigerated cargo liner Empire Star (12,656 tons). The ship maneuvered suspiciously and failed to answer any challenges or calls, so Phoenix prepared to open fire. Only then did Empire Star comply with the cruiser’s directive to turn 090° to starboard, and watchstanders used photographs to identify her just as the merchantman belatedly flashed her call. At 2124 Phoenix received a signal directing Langley to detach and make for Tjilatjap “with all dispatch.” Langley thus left the convoy and turned for Java. Phoenix received a “garbled” message three days later directing Sea Witch to also break away and steer toward Java “with all dispatch,” and the freighter detached and proceeded independently.

Planners arranged for a British cruiser of the Eastern Fleet to relieve Phoenix in the vicinity of Cocos Island, and for the American cruiser then to come about or to escort additional ships. On the 26th Phoenix received word that British light cruiser Enterprise (D.52) would be the ship to relieve the U.S. cruiser of her charges.

Edsall (DD-219) and Whipple (DD-217) meanwhile rendezvoused with Langley and Sea Witch but an enemy reconnaissance plane spotted them on 27 February 1942. Nine Japanese two-engine naval land attack planes and six fighters irreparably damaged Langley 74 miles from Tjilatjap. Edsall and Whipple shelled and torpedoed the tender but the possibility of renewed attacks compelled the survivors to retreat and they did not record her sinking. Some of the crewmen were transferred to Pecos (AO-6) and on 1 March endured the demise of another ship when Japanese Aichi D3A1 Type 99 carrier bombers from carriers Akagi, Kaga, Hiryū, and Sōryū sank Pecos south of Christmas Island. Sixteen men from Langley died altogether. Sea Witch delivered the 27 crated Warhawks to Tjilatjap on 28 February.

While this tragedy played itself out, other Allied ships attempted to escape the debacle or reinforce their far flung bastions. The leading convoys of the “Stepsister” movement carrying Australian troops back from the Middle East to defend their mother country steamed south-eastward for Australia. Such ships of the Eastern Fleet, and other British vessels available in the Indian Ocean, had their hands full escorting the vulnerable troopships.

Enterprise relieved Phoenix at 1621 on 28 February 1942, about 300 miles west of Cocos Island. “Katoomba passed out of sight still smoking and still behind,” Fischer recorded. “What a relief!” The convoy continued on toward Indian waters, while Phoenix, which Allied leaders conceded could not affect the outcome of the ABDA’s collapse, swung around and made for Fremantle. Helfrich ordered Phoenix to proceed to an area at 15°S and 115°E on the 1st, to help gather various small vessels escaping from the enemy and lead them to Exmouth Gulf, Australia.

Japanese ships hunted for these survivors and that morning Phoenix received a chilling message that two enemy cruisers and a pair of “large vessels” had been sighted near 10°20S, 108°32E. The following morning an unidentified plane appeared astern of Phoenix and shadowed her for about an hour before winging off. Phoenix had no choice but to continue and hope that she could elude the enemy net, and on the morning of 3 March the warship encountered patrol vessel Isabel (PY-10) and Sea Witch. Isabel scarcely eluded the hunters, and heavy seas furthermore pounded the converted yacht, and she steamed with some of her plates sprung and deck fittings broken. The previous day, the Dutch had dumped the crated Warhawks that Sea Witch delivered into the harbor to prevent their capture, and the freighter embarked 40 fleeing soldiers and just barely slipped out of Tjilatjap ahead of the enemy.

The Americans met Australian minesweeper Bendigo (J.187) at 1700, which also narrowly skirted death at Tjilatjap. A twin engine plane had also flown over the Australian ship, sometimes referred to as a corvette, earlier that morning, though the American and Australian crewmen were unclear as to whether they sighted the same shadower. All of the vessels nonetheless continued to steam independently at different speeds, and Phoenix reached Freemantle on 5 March. Two days later Isabel slid into the port with barely two hours of fuel remaining, and Bendigo followed suit the following day, carrying her last day of rations.

Convoy MS-5 meanwhile continued uncertain about the movements of Japanese ships and aircraft and consequently charted a course many miles to the south of Christmas Island, in order to avoid detection. Enterprise, Willard A. Holbrook, Duntroon, and Katoomba reached Colombo, also on 5 March, and some of them continued on to Karachi, India [Pakistan], where they arrived on the 13th. Phoenix helped escort a convoy from the Middle East to Australian waters, and lay to at Freemantle on 17 May 1942.

The Japanese continued their tide of conquest as they thrust into the Solomon Islands, and the Allies counterattacked them in Operation Watchtower—landings by the 1st Marine Division on Japanese-held Guadalcanal, Florida, Gavutu, Tanambogo, and Tulagi on 7 August 1942. The fighting for possession of the islands seesawed back and forth, and the Pacific Fleet deployed additional forces to the region. TF 17, Rear Adm. George D. Murray, steamed into those contested seas and as the ships crossed the equator, Vice Adm. Robert L. Ghormley, Commander, South Pacific Force (ComSoPac), ordered Murray to “proceed to a prospective rendezvous” with TF-61, Rear Adm. Frank J. Fletcher, in the waters to the eastward of the southern Solomon Islands on 27 August 1942, “prepared for offensive operations to the westward.”

Murray led Hornet (CV-8), Northampton (CA-24), Pensacola (CA-24), San Diego (CL-53), Hughes (DD-410), Morris (DD-417), Mustin (DD-413) O’Brien (DD-415), Russell (DD-414), and Guadalupe to that area at a speed of advance of 16 knots. Two days later Hornet sighted TF-61 approaching, which consisted of two task forces. TF-11, commanded by Vice Adm. Fletcher in Saratoga, also comprised North Carolina (BB-55), Minneapolis, Australia, Australian light cruiser Hobart (D.63), and several destroyers. In addition, TF 18 consisted of Wasp (CV-7), wearing Rear Adm. Leigh Noyes’ flag, Portland (CA-33) and Salt Lake City (CA-25), and several destroyers. Hornet and her attendants thus became TG 61.2, with Salt Lake City being assigned to their number.

Phoenix steered for the combined task forces and at sunset on 30 August 1942, she relieved Salt Lake City in TG 61.2. Salt Lake City, Bagley (DD-386), and Patterson (DD-392) escorted Wasp while she detached to fuel and take on provisions at Nouméa, New Caledonia.

The following morning at 0746, Japanese submarine I-26 (Cmdr. Yokota Minoru, commanding) torpedoed Saratoga’s starboard side, Hornet’s war diarist noting “the column of water rising to a height slightly higher than the height of her mast.” Saratoga came about for repairs, and with Enterprise requiring repairs after having been damaged in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, only Hornet and Wasp remained fully operational in the South Pacific.

Shortly before sunset, Fletcher ordered Murray to proceed independently with TG 61.2, remain in the area, and fuel on 2 September. Phoenix, Bagley, and Patterson were to split off and report to TF 44, then chart a course for Brisbane in company with Australia and Hobart. Monssen (DD-436) kept the enemy submarine down until sunset, but, as Hornet’s chronicler noted, “no indication received by this ship that the submarine had received any damage from our forces.” The day continued to its end, with no further contact with the enemy and the radar picking up occasional unidentified aircraft that turned out to be, upon investigation, “friendly…with ineffective identification equipment…”

Phoenix called at Brisbane and then joined the fighting to clear the Japanese from southeastern New Guinea. In the Battle of Milne Bay, the Allies repelled Operation Re, a Japanese counterattack against the Allied airfields there (24 August–7 September 1942). Early in the battle on the 24th, seven Japanese barges landed approximately 350 men of the Kaigun Rikusentai (Special Naval Landing Forces—SNLF) on Goodenough Island in the D'Entrecasteaux Islands to rest. The Allies discovered the convoy and a dozen RAAF Kittyhawks (Curtiss P-40s) pounced on the barges and sank all seven of them, stranding the enemy ashore. The Japanese operated aggressively, however, and as they evacuated their surviving SNLF from the aborted landings, light cruiser Tatsuta and destroyer Arashi swung around and bombarded the Gili Gili and Waga Waga areas on the night of 7 September 1942. The Japanese sank British armed motor vessel Anshun (3,188-tons), killing two of her gunners and wounding two more, and then came about and retired.

British Rear Adm. Victor A.C. Crutchley, RN, led a strike force from the Southwest Pacific Force, comprising Australia (the flagship), Phoenix, Hobart, Bagley, Helm (DD-388), Henley (DD-391), and Selfridge, from Brisbane on the 7th to deter the thrust and to catch Tatsuta and Arashi. The Allies meanwhile learned that Japanese destroyers Isokaze and Yayoi attempted to slip past the Allied net and rescue their beached men on Goodenough Island, and so Crutchley turned to intercept them. USAAF North American B-25 Mitchells and Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses attacked the pair, however, and sank Yayoi about eight miles northwest of Vakuta Island on 11 September. Following additional fighting, the enemy later evacuated the survivors from the island. In the meanwhile, Crutchley charted a new course to an area about 300 miles south of Milne Bay that he believed to be out of range of enemy land-based planes, and the ships patrolled ready to meet any Japanese thrust into those waters. While Phoenix served with the force in November she operated a trio of SOC-3s of VCS-9.

Phoenix, Hobart, Helm, Mugford (DD-389), and Patterson next sailed together as TF 44 and took part in Operation Lilliput, escorting convoys that transported troops and cargoes back-and-forth between Milne Bay and Oro Bay, in southeastern New Guinea. The movements largely supported the 32nd Infantry Division and the 7th Australian Division as they fought a bloody campaign to oust the Japanese from their positions around Buna, Gona, and Sanananda. The many reefs and shoals along the coasts often prevented larger ships from closing the shore, and the task force protected their charges from a distance while the mostly Australian or Dutch vessels, which included a variety of barges, landing craft, and similar lighter draft auxiliaries, plied the coastal waters.

The ship visited Brisbane in April 1943, and then turned eastward from Australian waters for an overhaul at Philadelphia Navy Yard. At that time, she carried a mix of planes from VCS-9: one SOC-1, a single SOC-3, and an SON-1. Helm and Australian destroyer Arunta (I.30) rendezvoused with the cruiser in China Strait at 0640 on the day before Independence Day 1943, and they proceeded together into Milne Bay, where Phoenix moored starboard side to British tanker Bishopdale (A.128) at 1745. Phoenix subsequently headed for home and then (12 May–29 August) accomplished the overhaul at Philadelphia.

The ship completed her post yard work-ups, and then embarked Secretary of State Cordell Hull and carried her important passenger to Casablanca, Morocco (7–15 October 1943). Hull flew on to the Moscow Conference, a series of meetings between key Allied leaders to discuss the war effort against the Axis, held in the Soviet Union. Phoenix was then assigned to the Seventh Fleet and sailed again for the South Pacific via the Panama Canal.

Phoenix moored starboard side to Monongahela (AO-42) and refueled while at Espíritu Santo on 1 December 1943. The ship also loaded 2,000 rounds of 5-inch projectiles for transfer to the Service Force and set out again that evening. Phoenix shifted to berth H-1 on the morning of the 4th and transferred the ammunition. She then (6–7 December) trained with TF 74 in the Coral Sea. The task force also included Australian heavy cruisers Australia and Shropshire (83), Nashville, Helm, Ralph Talbot (DD-390), and Australian destroyers Arunta and Warramunga (I.44). Phoenix returned to Milne Bay and anchored in the now familiar H-1. The ship joined Shropshire in practice shooting at Shortland Island on the 10th, and upon her return shifted to berth K-3. On the 14th she received an air raid warning and manned her air defense stations, though the raiders did not materialize. Nashville and Phoenix carried out antiaircraft practice on 20 December, and during the succeeding days the latter fueled again from Bishopdale and loaded ammunition to prepare for her next endeavor. Rear Adm. Russell S. Berkey, Commander, CruDiv 15, broke his flag in Phoenix on the 23rd.

The day after Christmas 1943, Phoenix resumed operating with TF 74, which Crutchley divided into two task groups. TG 74.1 consisted of Australia -- his flagship -- Shropshire, Helm, Ralph Talbot, Arunta, and Warramunga. TG 74.2 comprised Nashville, Phoenix, Ammen (DD-527), Bache (DD-470), Bush (DD-529), and Mullany (DD-528). The Seventh Amphibious Force, led by Rear Adm. Daniel E. Barbey, meanwhile hammered the Japanese on Cape Gloucester, New Britain. The sea was smooth and the wind calm on the morning of 26 December, as the 1st Marine Division, Maj. Gen. William H. Rupertus, USMC, landed at the cape during Operation Backhandler.

Phoenix steamed with Fire Support Group Baker, which formed a column (in order) of Bush, Nashville (the officer in tactical command—OTC), Phoenix, and Bache, passed through the Vitiaz Strait at an average speed of 10–12 knots, around Rooke Island to the eastward, to the north of Sakar Island, and entered their firing area before sunrise. Ammen and Mullany broke away from the column and screened the vessels from submarines to the northeast. The ships and landing craft of the Eastern Assault Force passed close aboard on their way to the transport area in Borgen Bay on western New Britain.

Phoenix fired at the Japanese troops defending Yellow Beach Area No. 1, along the northwest perimeter of Borgen Bay (0627–0725 on 26 December 1943). The ship shot mostly as planned, though five Mk 29-1 fuse tips broke off a result of overzealousness on the part of the shellmen, causing three jams. The gunners cleared the jams and continued firing. Phoenix used her SG radar in conjunction with charts of the target area prepared to the same scale as the remote planned position indicators. With the SG designation as a basis, the crew used the Mk VIII radar to furnish an accurate reference point for the actual firing.

The plans called for the warship to continue shooting until 0727, but at 0725 she ceased firing so that USAAF B-25s could bomb and strafe Target Hill on low altitude runs. The Mitchells dropped eight tons of white phosphorous bombs which, combined with the shellfire and other bombing, mostly obscured the enemy’s vision. Planners allotted Phoenix 1,000 6-inch rounds for the bombardment, but the bombers and strafing by other aircraft compelled her to cease fire early and she shot 897 6-inch shells.

Stationing Phoenix so closely to the column of assault vessels (immediately ahead), Capt. Albert G. Noble, her commanding officer, concluded, “did not permit the Task Force to develop fully its potential strength as an advance screen, and further that this close stationing deprived this Task Force of the opportunity for free maneuvering in event of contact with enemy surface forces.” Noble vented his frustration that the cruisers fought for nearly four hours confined within a very small area while travelling at low speed. “It is considered that this employment entails a serious risk to ships of this type, which should be avoided whenever possible.” The captain ended his report on a positive note by adding that Cape Gloucester marked Phoenix’s first battle since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor two years before, “and the conduct of the bombardment reflected accurately the careful preparation and training which had been conducted in all departments for this action”.

The cruiser had no sooner ceased shooting when the threat of an air raid compelled her to man air defense stations and increase speed to 25 knots, but the enemy did not attack the ship. The marines quickly established a beachhead, though encountered stiffening resistance as they pushed inland. The task force thus came about at 0811 and as the ships steamed through Vitiaz Strait during the afternoon watch, Bache sighted enemy planes to the eastward. During one such raid the Japanese tragically sank her former consort Brownson (DD-518) off the cape near 05°20'S, 148°25'E. Enemy aircraft, some of them tentatively identified as Kawasaki Ki-61 Tonys, attacked the column, and one of the planes dropped a 500-pound bomb that splashed in the water near the cruisers. The enemy also inflicted casualties on Mugford and Shaw (DD-373), and some of the ships fired at the attackers without result. Phoenix anchored in Buna Roads, New Guinea, at 2210 that night.

Australia, Shropshire, and Phoenix anchored in Dyke Ackland Bay, approximately 14 miles northeast of Port Harven, New Guinea, over the New Year (31 December 1943–1 January 1944). On New Year’s Day, operations in other areas temporarily denuded them of escorts as all of their destroyers served with TF 76. Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid, Commander Seventh Fleet, expressed his concern that the cruisers should be thus exposed and suggested that they shift to a more protected anchorage, and TU 74.1.1 accordingly steamed to Milne Bay, and intermittently operated from there and Porlock Bay. Phoenix sometimes deployed her Seagulls ashore and on 11 January, she transferred one of the two SON-1s there to Nashville. The latter ship picked up the plane while she steamed to Sydney, Australia, for leave and liberty (11–30 January), and Shropshire relieved Nashville within TU 74.2.1. Phoenix operated three Seagulls and Nashville two as a result of the switch. Phoenix’s third aircraft operated ashore until the afternoon of the 16th, when the ship hoisted it on board.

On the night of 25–26 January 1944, the ship took part in a night raid on Madang and Alexishafen, New Guinea. Commodore Homer W. Graf, Kinkaid’s chief of staff, embarked on board Phoenix for the battle. The ship launched her Seagulls ashore to a seaplane base at Samarai Island in the Louisiade Archipelago on the 23rd, and the following day set out in company with Boise and Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 48, which operated as TU 74.2.2. En route the cruiser held antiaircraft target practice against sleeves towed by Grumman J2F Ducks and her own planes. “Marksmanship of [PHOENIX] automatic weapons,” Capt. Noble proudly recorded, “shows splendid improvement as result of daily tracking drills.”

Boise and Mullany sheered off to starboard and raided Alexishafen and then rejoined the column (0100–0330 on 26 January 1944). Ammen, Bush, and Phoenix in the meantime formed a column ahead, and the destroyers steamed in the van and were directed to maneuver with enough freedom from the formation so that all of their guns could bear as the trio blasted the enemy positions (0130–0206). The Japanese did not resist heavily, though they fired tracers from an (estimated) 25-millimeter gun that fell about 2,000 yards short of Phoenix. The left recoil cylinder in a gasket in the cruiser’s No. 3 5-inch gun split during the bombardment and subsequently required repairs that temporarily (30–31 January) put the gun out of commission. Following their shelling, the ships watched Boise and Mullany bombard the enemy. Unidentified aircraft reports repeatedly punctuated the night, and at 0320 Phoenix watchstanders sighted flashes to starboard, which they presumed to be PT boats firing at Japanese planes.

As the ships retired, 16 USAAF Republic P-47s flew a combat air patrol (CAP) protectively overhead, and then 16 Lockheed P-38 Lightnings relieved the Thunderbolts. Many of the sailors considered the extensive fighter cover the strongest they had yet seen over ships in the area. On the morning of the 26th, Boise, Phoenix, Ammen, Bush, and Mullany passed Bache, Beale (DD-471), and Daly (DD-519) at high speed in Vitiaz Strait as they returned from shelling the Japanese on Alexishafen and Madang on the north coast of New Guinea.

Two of the cruiser’s planes returned to her on the 26th and were hoisted on board, followed on the 27th by the third Seagull. Phoenix periodically stood air defense alerts while anchored in Milne Bay, and one such took place (1000–1125) on 2 February 1944, when she intercepted a transmission from Radio Milne that the radio station at the seaplane base at Samarai was shutting down due to an air raid. The ship manned her battle stations and prepared to get underway, but enemy aircraft did not attack the warship and she resumed her normal routine when the “All Clear” sounded.

The crew contended with the Japanese but also with the balmy weather, mosquitoes and a wide variety of tropical insects, and shortages of provisions. “While our lack of provisions has never become acute,” Noble reported, “this is due largely to the fact that we have been able to wheedle some amounts from transports and merchant ships.” Phoenix drew provisions from newly arrived Calamares (AF-18) on 5 February, and the captain elaborated that adding Calamares and Octans (AF-26) to “assist the hard-worked [MIZUR] [Mizar (AP-12] and [MERKUR] [Mercury (AK-42)] should greatly improve what has been an unsatisfactory situation. The [CALAMARES] does not carry a large stock, but it is well-rounded and of good quality.”

Rear Adm. Berkey shifted his flag to Boise on the 10th and the next day Phoenix set out for a well-deserved ten-day period of rest and recreation at Sydney. The admiral and his staff flew to the city to meet the cruiser, which experienced problems with her steering engine en route. An RAAF Bristol Beaufort provided intermittent air cover as Phoenix slid past South Head and the Degaussing Range, and moored port side to berth No. 2 at Sydney’s Circular Quay at 0929 on 13 February. On the morning of the 24th the cruiser turned her prow to sea in company with Beale and Mullany, and made for Brisbane. The destroyers came about and returned to Milne Bay as the cruiser reached the entrance to the city the following day, and she then proceeded up the swept channel of the Brisbane River and at 1220 moored port side to No. 3 Newstead Wharf.

Rear Adm. Berkey and Capt. Noble left the ship soon after she moored to confer with Vice Adm. Kinkaid, who informed them that Phoenix was to take part in Operation Brewer—landings by the 1st Cavalry Division, Maj. Gen. Innis P. Swift, USA, in the Admiralty Islands. The invasion primarily continued the Allied strategic encirclement of the Japanese garrison at Rabaul on New Britain. Kinkaid and Gen. MacArthur, Commander, Southwest Pacific Area, decided to accompany the force for the initial landings on board a warship, and Phoenix was large enough to accommodate the two men and most of their staffs. Phoenix was to set out as soon as possible in order to reach Milne Bay by noon on 27 February.

The cruiser still lay at Brisbane, however, and more than 300 of her men were ashore. At 1505 Phoenix cancelled all liberty, as well as planned target practice for the following afternoon off Cape Morton, and made ready to recall the crew. Shore patrols hurriedly scoured the port, and the ship contacted the naval officer in charge at Brisbane and requested that he pass the code-word for the recall. Trucks with bull horns roamed through the city and broadcast the recall, and Phoenix requested a tug and pilot. The ship cast off her mooring lines and edged away from the pier at 1709 with 22 absentees. Eight men clambered on board from small boats during her progress down the river so that, when the ship held quarters for muster at half past the hour, she counted only 14 absentees. The authorities continued to hunt for the men, and subsequently rounded them up and arranged for a USAAF Douglas C-47 Skytrain to fly them to Milne Bay on the afternoon of the 26th. Phoenix cleared the swept channel at 2111, rang up 27.8 knots, and surged toward her destination. Before the ship entered China Strait she launched a plane carrying flag operations officers to a conference with TF 76 regarding Brewer. The ship slid into Milne Bay and moored port side to Bishopdale at 1209, just nine minutes past her scheduled arrival. Thirteen absentees returned to the ship after she tied up, and the aircraft returned the flag operations officers.

Kinkaid and MacArthur and their aides boarded Phoenix at 1618 on 27 February 1944, and at 1635 the ship cast off her lines and joined Nashville, Bache, Beale, Daly, and Hutchins (DD-476). Phoenix served as the flagship of TG 74.2, Nashville as TU 74.2.1, and the destroyers as TU 74.2.2, with Daly as their flagship. The ships steamed 18 knots through the Raven Channel and anchored in Buna Roads, New Guinea, at 0524 on the 28th. At 0954 Phoenix swung her prow around to seaward again as the ships of the task force set out for the landings. Phoenix moved to the Admiralty Islands via Cape Ward Hunt, Cape Cretin, and Vitiaz Strait to operate with the Seventh Amphibious Force as it landed the reinforced 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, and supporting elements, including men of the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit, in a reconnaissance in force on Los Negros Island on 29 February.

At 2114 on the night before the landings, 28 February 1944, Phoenix experienced some tense moments as an unidentified vessel appeared out of the darkness. Beale illuminated her with a searchlight and the mysterious vessel turned out to be submarine chaser PC-1123. The ships reached a point about ten miles south of Los Negros Island at 0600 on 29 February 1944. At 0552 they divided to support the landings and Phoenix, Daly, and Hutchins, in column ahead in the order named, tackled Los Negros, while Nashville, Bache, and Beale bombarded the Lorengau area. Phoenix, Daly, and Hutchins steamed at 15 knots (0624–0643) to a point about 5,000 yards south of Southeast Point, Los Negros.

Phoenix reversed course to enable her to reach the first firing point at 0740. At 0711 the ship launched Plane Nos 2 and 4 to spot for both of the cruiser groups. When H-hour arrived at 0740, Phoenix charted a course of 050° at 12 knots as she opened fire to port on Japanese positions southwest of an airstrip at Momote. A Japanese shore battery of two guns, estimated to be 3-inch pieces, returned fire. The cruiser’s 5-inch guns hurled 131 rounds at the enemy and silenced the battery. The ship’s diarist observed that her fire “was rapid and accurate; only one salvo from the beach being observed after opening counter fire.” Kinkaid and MacArthur watched from Phoenix’s flag bridge as the vessels bombarded the enemy, and while the troopers landed.

The ship checked her shooting 15 minutes later while USAAF Consolidated B-24 Liberators bombed and strafed the target area and the beaches. Phoenix swung around again at 0800 to 230° and 12 minutes later (0812–0814) unleashed her 6-inch and 5-inch guns against the Japanese to starboard. Enemy 40 or 25-millimeter rounds splashed close aboard and she immediately replied with counterbattery fire against a 500 yard sector of the beach, and effectively silenced those guns as well after shooting 104 5-inch shells. Berkey abruptly ordered the warship to cease fire to avoid endangering the assault waves.

One of the cruiser’s Seagulls, flown by Lt. Richard W. Molten, USNR, and ACRM Edward G. Berkery, completed its bombardment observation mission and then noticed that heavy Japanese machine gun fire held up several waves of assault boats approaching the landing in Hyane Harbor. No other Allied planes flew nearby, but Molton and Berkery nevertheless disregarded the lack of fighter cover or support, boldly dropped to low altitude, and bombed and strafed the machine guns. The Seagull’s attack destroyed one 25-millimeter emplacement, and drew the fire of the others skyward upon itself, enabling the landing boats to get through. The antiaircraft fire damaged the plane but the Seagull kept shooting until it exhausted its ammunition. Berkery handled his free guns with such consummate skill and energy that the aircraft dealt “damaging punishment with each pull out”. Capt. Noble recommended Molten for the Navy Cross for his “courage and initiative above and beyond the call of duty”, and Berkery the Silver Star for his “extraordinary courage, skill and perseverance”. The Navy instead awarded Molten the Distinguished Flying Cross and Berkery the Air Medal. Their recommendations also noted that they flew the mission in “an obsolete observation seaplane”.

Phoenix came about again at 0934. Hutchins reported a possible Japanese submarine while the attack ships steamed back and forth off the entrance to Hyane Harbor at 1307, and Daly investigated but considered the results negative. Following the landings, the ships retired at 22 knots toward Cape Sudest, New Guinea. During the morning watch on 1 March 1944, Phoenix left the formation and at 0759 rendezvoused with a motor torpedo boat off Nussing Island, in the vicinity of Cape Cretin, where the PT boat eased alongside so that MacArthur, Kinkaid, and their aides could climb into her. “This is an excellent ship,” the general observed as he disembarked. “In my opinion, I have never seen a more efficient ship.” Kinkaid added, “You have a remarkably fine, clean, and efficient ship. I marvel at the quietness with which everything is done.” Phoenix returned to Buna Roads.

Sporadic squalls and heavy clouds provided cover from air attack during the first few days of the month, and the crew thus grew increasingly grateful for the foul weather. The Allies intended to capture the entire eastern end of Manus Island and destroyer minesweepers attempted to sweep the channel into Seeadler [Sea Eagle] Harbor, but enemy 4-inch shore batteries on Hauwei Island twice drove them off. Allied intelligence analysts believed that the Japanese emplaced as many as five guns (of up to 5-inch) on the island, and thus decided to knock out the artillery positions so that they could continue the campaign. On 4 and 7 March 1944, Rear Adm. Crutchley took TF 74, comprising Shropshire, Nashville, Phoenix, Bache, Beale, Daly, and Hutchins, to bombard Hauwei and Norilo Islands of the Admiralty Group. Shropshire, Nashville, and Phoenix used air spots from the ship’s pair of SON-1s to lash the targets to starboard from a range of 4,000 yards during the first battle (1609–1651 on the 4th).

The enemy batteries shot heavily against the ships but ceased firing when shells from the cruisers burst in their vicinity. The vessels then came about and steamed what Capt. Noble described as a “deceptive southward course” to open the area, before reversing course and then steadying up due west. The ship’s watchstanders surmised that their shelling destroyed most of the Japanese batteries because only a single gun resumed fire during the following days. Planners failed to allocate even a single platoon to land and secure the beaches, however, or to direct the destroyer minesweepers to return and complete their sweeps covered by the cruisers, errors that Noble lamented in his report on the actions. Berkey went one better and Noble reported that the admiral “did not consider yesterday’s bombardment of fullest value unless arrangements were made for occupation forces to take advantage of the positions we had neutralized”.

Their estimate of the situation proved overly optimistic, however, when Japanese guns on the island opened fire on Allied ships again on 7 March 1944. Intelligence analysts postulated that the enemy ferried the pieces over from the mainland under cover of darkness. Phoenix and her consorts were zigzagging on patrol north of the Admiralties, and beginning to retire to Buna in time to pass through Vitiaz Strait at daylight the following morning, when they received word of the attacks. Berkey recommended against a second bombardment until the occupation forces were ready to take advantage of the shelling, but stated that a “co-operative consultation” with his Army counterparts seemed indicated. The ships thus swung around and Berkey and his chief of staff transferred to Beale and ashore for the meeting (0956–1500). The Army officers revealed that they lacked the troops and equipment to occupy the neutralized positions before the 10th.

Nashville, Phoenix, and Hutchins therefore used aerial spotting to pound the four “most urgent” targets along the east tip of Hauwei Island, about 50–100 yards along the north coast, and a single gun each on Karuniat, Ndrilo, and Pityilu Islands, and on Mokerang Point, as well as a light antiaircraft gun on Ndrilo, during the 1st dog watch (1635–1712 on 7 March 1944). Nashville fired first from a range of about 5,000 yards, followed by Phoenix with all of her batteries that would bear from 3,550 yards. Both ships shot at Target Nos 1 and 2, and because of their positions in the formation, Phoenix arranged to fire at Target No. 2 while Nashville engaged the first one. The Japanese did not return fire.

Following the assigned barrage, observers peering through optical rangefinders and directors sighted a gun mount through the smoke near Target No. 1, and Nashville resumed firing against the area. Her first 6-inch salvo detonated a large explosion, most likely the battery’s ammunition dump, which blew away its protective camouflage and tilted the gun over on an angle, leading the observers to consider it knocked out. Phoenix’s gunners set two thirds (122) of the 183 6-inch rounds she fired to base detonate after penetration, and the remaining third (61) with steel nose plugs to penetrate any concrete encountered. In addition, one of the ship’s Seagulls spotted a 4-inch gun emplacement and dropped two 100-pound bombs that missed and landed about 40 feet from the gun, and fired 500 rounds of .30 cal. ammunition. The aircrew did not spot any enemy troops manning the gun, though it is likely the gunners sought shelter during the shelling. Following the barrage, Phoenix took station behind Shropshire and opened the range, though an unidentified aircraft triggered an air defense alert (1757–1803) until it passed without attacking.

The ship’s company continued to appreciate the foul weather that helped them to avoid enemy planes but they required accurate meteorological forecasts. The Australians broadcast for the region but Japanese action prevented them from including adequate data on the area northwest of New Guinea. On the 11th, therefore, Phoenix sent her aerologist to the seaplane base at Samarai to gather information on weather broadcasts.

The Japanese repeatedly displayed operational expertise against Allied ships during night fighting, and Phoenix alternatively took part in a series of exercises, broken by periods of upkeep while anchored in Milne Bay. During one such battle problem on the night of 7 April, a Red Force (Phoenix and Nashville’s) plane discovered the opposing Blue Force ships and attempted to drop flares to illuminate them but the flares failed to ignite. Their opponents shot star shells, considerably aided by the light of the full moon, but Phoenix, Nashville, and their destroyer screen laid smoke screens, abetted by a favorable wind. Phoenix evaluated the training and noted that “the result demonstrated to our satisfaction that stack smoke can be a very effective countermeasure to night illumination”.

TF 58, Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher, supported the assault of the Army’s I Corps at Aitape and Tanahmerah Bay (Operation Persecution) and at Humboldt Bay on Hollandia (Operation Reckless) on the north coast of New Guinea. Phoenix prepared for the battle as she shifted her berth from Milne Bay to Buna Roads on 15 April 1944. On the 18th, the cruiser stood down the channel as part of TG 75.3, Covering Force Baker (Fire Support Group Charlie) of the Central Attack Group, which also comprised Boise, Nashville, Abner Read (DD-526), Bache, Beale, Daly, and Hutchins. Berkey broke his flag in Phoenix in command of the group. The ships rendezvoused with the balance of the attack force northwest of Manus Island early on the 20th.

They encountered excellent visibility with a clear sky and no moon on 21 April 1944 until about 0300, when a squall overtook the formation from directly astern and reduced visibility to several hundred yards. The squall dogged them until just before 0436, at which time the group detached for their assigned fire support area. Five heavy and seven light carriers launched preliminary strikes on Japanese airfields around Hollandia, Sawar, and Wakde. Phoenix hove to at her station and stopped all engines, and at 0800 opened fire with both her main and secondary batteries to starboard, and 15 minutes later the ship swung around and brought her port guns to bear. In between the salvoes she opened up with 40-millimeter guns against enemy positions ashore. Japanese light machine gun and small arms fire arched out toward the assault troops in Phoenix’s sector, but the warship did not observe heavy enemy resistance. The cruiser shot 363 6-inch, 366 5-inch, and 582 40-millimeter rounds.

The following day the carriers covered landings at Aitape, Tanahmerah Bay, and Humboldt Bay. A possible submarine sound contact compelled the ships to urgently maneuver at various courses and speeds until the sonar teams evaluated the echoes as false. Phoenix logged the weather on 22 April as “intermittently squally’, but added triumphantly that “while sill as much as 40 miles from our objective, the glare of a fire was visible against the sky, apparently a momento [sic – memento] of our recent bombing attacks.” The ship fought as part of the Central Attack Group, TG 77.2, as she shelled the coastline in the Humboldt Bay-Hollandia area that morning when the troops went ashore. Into the following day the light cruiser supported the soldiers as they consolidated their gains and prepared for further attacks along the northwest coast of the larger island.

Boise, Phoenix, Beale, Daly, and Hutchins retired overnight and during the afternoon watch on 23 April entered Seeadler Harbor. Phoenix marked the ship’s first return to the anchorage since she bombarded the enemy, “and the crew was interested in seeing the results of their handiwork still manifest in the broken trees and barren appearance” of Hauwei Island. Several tankers, ammunition ships, and merchantmen also lay anchored in the harbor, but the fledging anchorage’s development left “much to be desired.” Nashville, Abner Read, and Bache returned to Seeadler on the 25th.

The Allies sought to neutralize the danger of air attacks on their newly-won positions on New Guinea and carried out additional operations. Phoenix stood out to sea on 26 April 1944, and at 0710 sighted Indiana (BB-58), screened by Cassin Young (DD-793) and Prichett (DD-561), at a distance of 18,000 yards. The heartening sighting marked the cruiser’s first glimpse of a battleship in that area, and Indiana and her consorts made for Seeadler, where they rendezvoused with other ships of TF 58, and then charted a course to raid Truk Lagoon in the Carolines.