Omaha I (Screw Sloop-of-War)

1872–1914

The first Omaha was named for the river in Nebraska. Subsequent ships of this name honored the city in Nebraska.

I

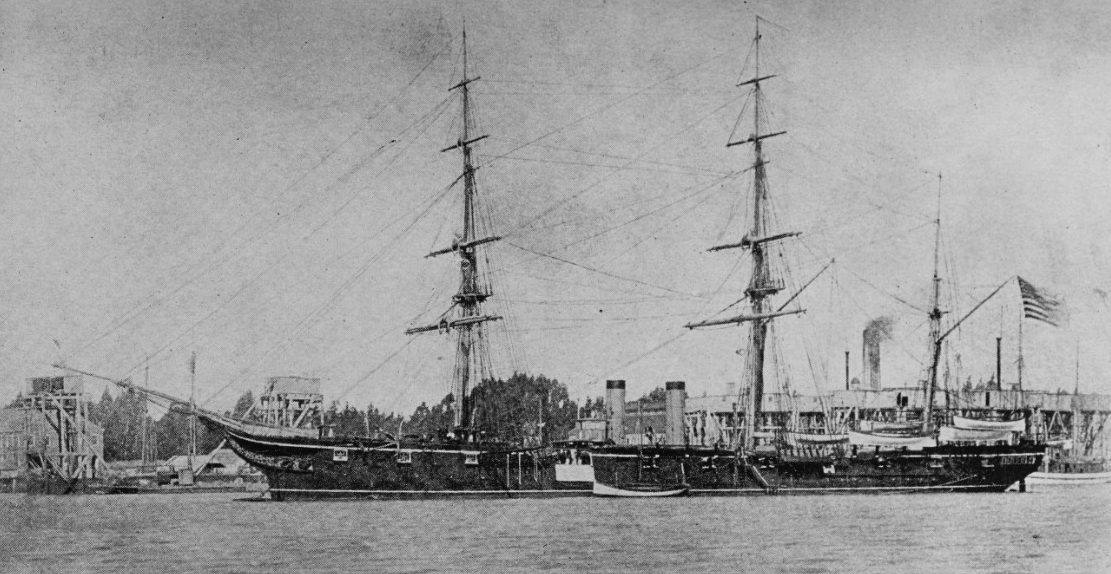

(Screw Sloop-of-War: displacement 2,394; length 250'6"; beam 38'; draft 17'6"; speed 11.3 knots; armament 1 XI-inch smoothbore, 10 IX-inch smoothbore, 1 60-pounder, 2 20-pounders; class Serapis)

The first Omaha was laid down in 1867 by the Philadelphia [Pa.] Navy Yard, as Astoria; launched on 10 June 1869; sponsored by Miss. Kitty Marchand, daughter of Commodore John B. Marchand; renamed Omaha on 10 August 1869; and commissioned on 12 September 1872, Capt. John C. Febiger in command.

Omaha served initially with the South Atlantic Station and then the South Pacific Squadron (8 October 1872–19 April 1878). The ship’s historian noted that she protected “American interests during political disturbances” and, in addition, surveyed the Juan Fernández Islands off Chile in March 1876. Rear Adm. George H. Preble, Commander, South Pacific Squadron, broke his flag in Omaha while she lay at Panama on 1 March 1877.

On 23 June 1876, steamer Georgia, which belonged to the Panama Transit Company, a U.S. concern, while on her way from New York to Panama in order to take her place on the route between that port and San Francisco, Calif., went ashore near Punta Arenas, Chile. The ship’s master employed a diver named Lasky from Montevideo, Uruguay, who examined the steamer and reported that the steamer could not be refloated. The master next applied to the local governor for an order for her sale, and Lasky’s partner -- a man named Jones and an Argentinean citizen -- purchased the ship for $950 Chilean.

The company meanwhile dispatched another steamer, Wilmington, Capt. Holmes in command, with wrecking apparatus, for the purposes of raising Georgia and with the authority to take charge of both ships. When Wilmington reached the area Holmes discovered that wreckers had taken possession of Georgia, but as the master inspected the ship, he believed that they could salve her. Holmes acted on his own initiative and paid Jones $14,500 for Georgia — $1,500 in cash and the balance of $13,000 in a draft from a firm in Valparaiso, Chile. The determined captain refloated the ship but she leaked and before he could get her ready to sail, the draft reached Valparaiso and the company declined to pay, on the grounds that the sale to Jones was collusive and in other respects invalid. Jones then brought a suit against Holmes and obtained from Valparaiso’s tribunal of commerce an order to embargo Georgia until the company paid the draft and the damages. The Chilean Army sent a lieutenant to board Georgia, but Holmes disregarded the order and stood down the channel with both ships, carrying the officer.

The pair of merchantmen ran short of coal and put in to Lota, Chile, but the local authorities attempted to detain them and dispatched another officer. Holmes, undaunted, coaled and turned the two ships to sea with both officers on board Georgia and made for Mejillones, Bolivia, where he placed both men on board a British packet and paid their passage to Valparaiso. The two vessels continued their cruise but heavy seas pounded them and Georgia leaked so badly that she turned for urgent repairs in dry dock at Callao, Peru. The ships made for that port during a time of turmoil when a Peruvian revolution led to the inconclusive Battle of Pacocha near Callao on 29 May 1877, in which Peruvian monitor Huáscar, Capt. Germán Astete in command, fought British frigate Shah and corvette Amethyst, led by Rear Adm. Algernon F.R. de Horsey, RN, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Station.

Georgia and Wilmington reached Callao on 11 May 1877, and four days later, U.S. Vice-Consul S.T. Kissam at that port called on Richard Gibbs, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of the United States, at the U.S. legation at the capital of Lima, and informed Gibbs that the Chilean consul invoked his authority to prevent Georgia from returning to sea. Holmes prepared a statement for Gibbs and the minister then advised Kissam to respond that the Chileans were not authorized to hold the steamer. The Chilean minister, meanwhile, requested that the Peruvians detain Georgia because the ship had set out while theoretically under arrest. The Peruvians did so on the 16th and ordered her to anchor under the guns of their screw frigate Apurímac. Recriminations flew back-and-forth and a crisis loomed as the Chileans formed an “extradition treaty” Joaquín Godoy, Minister of Chile in Peru, wrote to Gibbs that day, “which has been approved and ratified on the part of Peru, and in which is expressly mentioned the crime of piracy, of which Captain Holmes is guilty.” The captain craftily eluded capture, however, and sailed on board Wilmington on the 28th, leaving Georgia behind.

The Panama Transit Company petitioned the State Department for aid, and Secretary of State William M. Evarts telegraphed Gibbs on 4 June 1877 and instructed him to demand Georgia’s “immediate release,” noting that she was “forcibly detained.” Gibbs so demanded to the Peruvians on the 7th, and two days later they relented and released the steamer, but then the tribunal of commerce detained her again — on judicial process. The U.S. Navy in the interim dispatched Omaha to the crisis and she arrived at Callao on 14 June. Rear Adm. Preble and Capt. Edward Simpson, the ship’s commanding officer, went ashore and conferred with Gibbs, and the trio concurred that, as the Peruvians held Georgia in the midst of the judicial proceedings, they could not release her. Secretary Evarts nonetheless cabled Gibbs four days later and told him to complain about the ship’s original “unlawful detention,” as the “sole cause of involving her in judicial coercion,” and to make the ship ready for sea.

The Peruvians raised the judicial embargo on 28 June 1877, and Georgia stood out to sea that day. The company offered to settle the suit with Jones and pay him $16,220 Chilean, and to work out the damages via private arbitration. Georgia and Wilmington rendezvoused and resumed their voyage, and reached San Francisco by 22 August. “This Department is not aware,” Assistant Secretary of State Frederick W. Seward observed in response to Gibbs on 28 June, “that any definition of piracy under the law of any country would make Captain Holmes chargeable with that crime for his acts in Chile in respect to the steamer Georgia.” Omaha’s deployment to Callao lent weight to the Americans’ negotiations by acting as a symbol of U.S. resolve, and by transporting the admiral, and the ship remained there for some time. Ordered home on 22 October, Omaha completed repairs and prepared for her voyage, and then (4 December 1877–19 April 1878) rounded South America via the treacherous waters of Cape Horn and returned to the United States at Hampton Roads, Va., where Preble hauled down his flag.

Omaha there received orders to continue on to Portsmouth Navy Yard, N.H., where, on 9 May 1878, she was placed out of commission. The ship remained laid up in ordinary through 1881, and then (1882–1884) completed a refit. Following that work she was placed in commission on 16 April 1885, Capt. Thomas O. Selfridge Jr., in command.

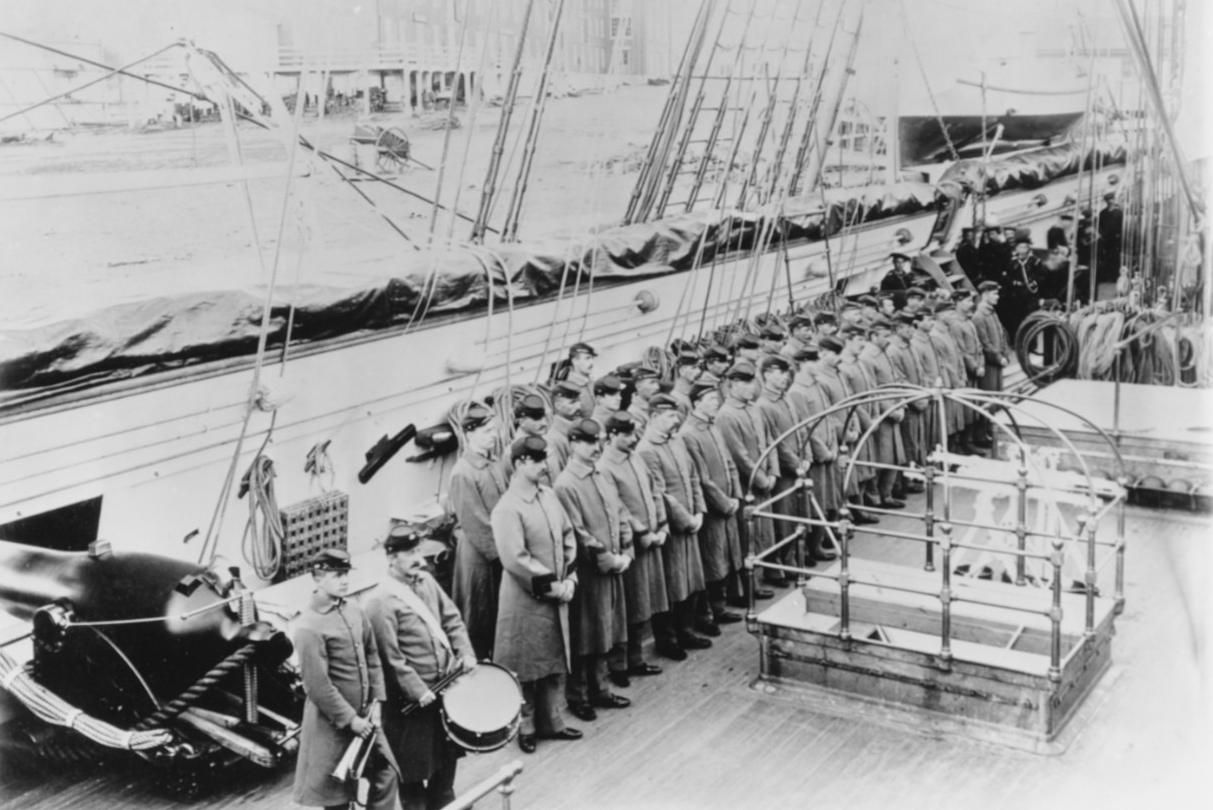

Selfridge initiated a number of unique practices on board the ship, one of which was to separate the apprentices as much as possible from the older men, subsequently reflecting upon many of the latter as “rough characters.” The captain detailed the apprentices to man “almost exclusively” the top-gallant and royal yards, and to form the crew of the captain’s gig, and later his barge. Selfridge often allowed the boat crews (with the exception of the boatkeeper) to land whenever he went ashore, and noted that few of them jumped ship, and “became quite proud” of their special privileges.

Omaha went to New York and on 12 August turned her prow toward the Far East to serve on the Asiatic Station, Rear Adm. John L. Davis in command, who was relieved by Rear Adm. Ralph Chandler on 22 November 1886. Omaha reached the region at a tense time because the Americans and Koreans had clashed in a series of incidents that escalated until (1 June–3 July 1871) U.S. naval ships attacked Korean positions ashore. The fighting strained relations between the Koreans and Americans for some time afterward, and the U.S. Navy deployed at least one ship whenever possible in those waters to protect Americans in the region. In addition, Omaha protected U.S. ships that sailed in Japanese and Chinese waters.

The warship therefore visited Chemulpo [Inchon], Korea, in October 1886. She then set out for Chefoo [Yantai], China, on 11 October, and on the 29th returned to Chemulpo. Omaha sailed on Halloween for Japanese waters and put in to Nagasaki on Kyūshū until just before Christmas on 20 December, when she turned her prow northward and chartered a course along the coast of Honshū for Yokohama, which she reached the day after Christmas. The ship completed repairs and upkeep into the New Year, and next (19 February–16 March 1887) set out for Kobe and Nagasaki, but returned to Yokohama following a tragic accident.

Naval regulations required the ship to exercise at gunnery every quarter, and while heading toward Nagasaki on the morning of 4 March 1887, Omaha fired at a target off Ikeshima, a small Japanese island that rises several miles to the west of Kyūshū. Numerous junks and fishing boats sailed in the area and Capt. Selfridge despaired of finding an area free from the danger of hitting them with the ship’s gunfire but finally choose a cliff, several hundred feet high, that rose near the end of the island, and the area near the cliff did not appear to be inhabited. The Americans anchored a target within about 50 yards of the island, where the cliff served as a backstop for “overs” and ricochets. In addition, they stationed a man aloft, and another in a boat abreast the target, to observe and report on the fall of shot. Selfridge did not apply to the local authorities for permission to carry out the gunnery drill, however, and failed to scout the isle for possible inhabitants. Omaha blasted the target with six 60-pounder rifled shells, six IX-inch rifled rounds with percussion fuses, and 30 round shells with five-second time fuses. The sloop-of-war ceased fire, the observers did not spot any unexploded rounds, and the ship came about.

Some Japanese lived on the other side of the island, however, and a crowd gathered and examined the fragments scattered near the area. The people discovered as many as six undetonated rounds and one of the men, who had worked in the arsenal near Nagasaki, attempted to explain a shell to the onlookers when it exploded, apparently when he accidentally struck a fuse or endeavored to extract it. The explosion killed him and three other Japanese islanders and wounded seven more people. When Selfridge learned of the calamity, he brought Omaha back to the island. The captain afterward recalled that he attempted to make “such amends as were possible,” and the ship’s company raised $600 from their own pockets, which they distributed to the islanders as partial compensation for their loss.

The islanders grieved their losses though accepted the Americans’ conciliatory efforts, however, Rear Adm. Chandler detached Selfridge from Omaha and ordered him to face charges of negligence during a hearing at Washington, D.C. Secretary of the Navy William C. Whitney disagreed with Chandler’s decision and directed Selfridge to return to Japan, and instructed the admiral to hold an inquiry in that country. The members of the court interviewed crewmen, examined the ship’s log and charts of the area, and, accompanied by witnesses, visited the island and viewed firsthand the scene of the tragedy. In addition, the court recorded several prior “instances of target practice with great guns under circumstances which, if not identical with, were, in some respects, similar to” Omaha’s shooting. The court of inquiry considered the captain negligent because he did not “thoroughly inform himself of the nature and character of the island towards which he was firing,” but did not hold him responsible for the accidental explosion. “No culpability,” Selfridge recalled the court’s principal findings, “was attached to my actions, yet I was not specifically relieved of blame.”

Despite the inclusive results of the inquiry, the captain wished to be exonerated and requested a court martial. He waited several months for an answer and then petitioned friends to discuss the matter with Secretary Whitney, who, in turn, ordered a court martial to investigate the incident. Rear Adm. James E. Jouett sat as president of the court and its ten other members, which convened at the Navy Department in Washington on 4 June and tried Selfridge for his alleged carelessness and “Neglect of Duty.” In addition to Selfridge, some officers of Omaha’s company also travelled to Washington and testified as witnesses, and after weighing the evidence and testimonies the court acquitted Selfridge on 12 June.

“When the unfortunate occurrence which gave rise to these proceedings was first reported to the Department,” Secretary Whitney observed, “the gravity of the case, the melancholy consequences which had followed so closely the target practice of the Omaha on the 4th day of March, 1887, the importance of the questions involved in any determination of responsibility, and the high standing of the commanding officer of the Omaha, all combined to make the investigation, thus imperatively demanded, one of unusual importance.”

“The additional evidence introduced on the trial of Captain Selfridge before the Court martial,” the secretary elaborated, “including his testimony on his own behalf, presents no new features which materially affect the conclusions reached by the Court of Inquiry. Such evidence was intended mainly, to show that Capt. Selfridge fully believed that, in reflecting the position he did, viz., off the island of Ike-Sima [Ikeshima], and within a marine league of the coast of Japan, without asking permission, and without more than a cursory observation of the island, he was simply following other precedents, or the example of other officers of high standing in the Navy clothed with responsibilities similar to his own; that, so far from neglecting suitable precautions, he took unusual measures to ascertain, while the fire was in progress, whether all the shell exploded, and had, as he supposed, sufficient reason to believe that they did; that it was therefore unnecessary for him to send a boat shore after the practice was over; that there was no sufficient indications of the island being inhabited to require him, in his judgment, to make, either before or after the firing, any special examination; that, from such observations as were made, he was warranted in believing, that the island was not inhabited; that the position selected, viz., in front of a high, precipitous bluff, was such as naturally led him to suppose, and warranted him in believing, that the practice could be had with absolute safety, and that there was not, in any step that he took or omitted to take, any culpable neglect of duty or any want or intentional disregard of possible danger to life, limb, or property.”

Jouett and the members of the court martial concurred with the court of inquiry’s determination, however, concerning Selfridge’s decision to carry out the gunnery training without first discovering if the island was inhabited and ascertaining to the particulars of the shooting locale.

“The Department cannot assent to the view that a naval officer may,” Whitney noted, “without blame, hold his target practice upon the soil of a friendly power without consulting such power, and, where he actually imperils life by the flight of the projectiles, without the previous examinations which would have disclosed such peril, and that he may sail away, with his full duty discharged, leaving unexploded projectiles to endanger innocent lives.”

Following further deliberations, Secretary of State James G. Blaine informed Mutsu, Munemitsu, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of the Japanese emperor, that on 26 February 1889, the Congress nonetheless approved a payment of $15,000 to the “Japanese Government on account of injuries caused to Japanese subjects by the explosion of shells from the U.S.S. Omaha.” Mutsu accepted the payment at Washington, D.C., the following month on 28 March.

“In acknowledging the receipt of this sum,” Mutsu replied to Secretary Blaine, “Count Okuma [Minister for Foreign Affairs Count Ōkuma Shigenobu] instructs me to express the gratification with which this action is regarded by his Imperial Majesty’s Government, and to say that they value it as another evidence of the spirit of justice and good will which the United States have so often displayed towards Japan.”

Omaha meanwhile resumed her patrols and shaped a course for Chemulpo, stopping for a day at Nagasaki en route (23–30 March 1887). The ship remained at that Korean port until 4 April, and then proceeded to Nagasaki, where she arrived two days later. Omaha headed northward again on the 1st of May, touched at Kobe, and reached Yokohama on 10 May. The sloop-of-war stood out of that growing port on 27 June, and three days later reached Nagasaki. She spent much of August (8th–29th) on a voyage to Chefoo and Chemulpo, and came about for Nagasaki. The ship steamed back to Chemulpo the following month (23–26 September), and on 16 November made for Fusan [Busan], which she reached on the 18th. The same day she stood down that channel for Japanese waters and visited Nagasaki (19 November 1887–6 January 1888). Omaha remained there until she left for Yokohama, where she arrived on 11 January, having touched at Kobe en route.

The ship set out eastward and crossed the Pacific to Panama (23 January–23 March 1888) and, in company with sloop-of-war Marion, received new officers and men at that Central American port. Omaha returned to sea on 5 May and called at: Punta Arenas [Puntarenas], Costa Rica; Corinto, Nicaragua; Amapala, Honduras; La Libertad, El Salvador; and San José, Guatemala. The ship wrapped-up her sojourn with a visit to Acapulco, Mexico (5–15 June), and then turned westward, called at Honolulu in the Sandwich Islands [Hawaiian Islands] (14 July–18 August), and returned to Yokohama on 15 September. On the 25th of that month she set out again for Chinese waters, touched at Kobe and Nagasaki en route, and called at Shanghai on 3 October. Rear Adm. Chandler died while in Hong Kong on 11 February 1889, and on 14 April Rear Adm. George E. Belknap reached the British Crown Colony and broke his flag in command of the Asiatic Station on board Omaha.

Belknap paid a visit to Yokohama in the latter part of 1889 and into the New Year, and during his stay at the port on the night of 8 February 1890, a fire broke out in the town of Hodogaya-ku, a ward of Yokohama. The conflagration spread rapidly and U.S. Consul General Clarence R. Greathouse requested that the admiral land a force from Omaha to assist the Japanese in fighting the flames. Belknap did so forthwith and the ship landed a large party, the marines led by 1st Lt. William C. Turner, USMC. The governor of Kanagawa Prefecture, in which the ward lay, cordially acknowledged the exceptional service that the sailors and marines rendered in helping the Japanese battle the blaze.

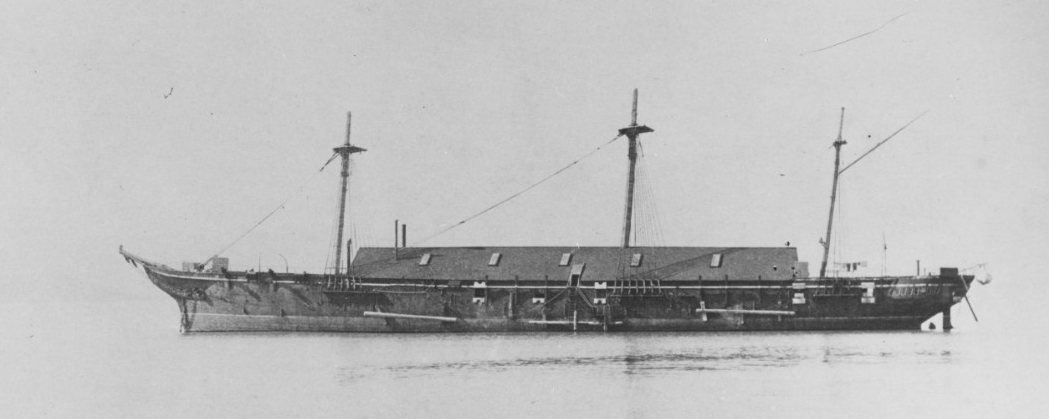

In 1891, the Navy directed Omaha to return to the United States. Rear Adm. Belknap transferred his flag from Omaha to screw gunboat Alliance on 9 March, and on 16 May Omaha arrived at Mare Island Navy Yard, Vallejo, Calif., where, on 16 June, she was decommissioned and placed in ordinary. She was never recommissioned, but was turned over to the Marine Hospital Service, an establishment of marine hospitals that primarily cared for sick and disabled seamen from the Revenue Cutter Service and Life-Saving Service, merchant mariners, and some federal employees.

Omaha subsequently anchored at San Francisco Quarantine Station, which was located on Angel Island in San Francisco Bay. The service used her there as a quarantine ship for infectious diseases, and the vessel also provided superheated steam from her boilers to disinfect ships and buildings. The station also included at times quarters for the steward and medical officer, attendant’s quarters (the staff normally comprised eight attendants), a boathouse, warehouse, disinfecting house, three barracks for steerage passengers, a hospital for people diagnosed with noncontagious diseases, a lazaretto (quarantine station for maritime travelers), pump house, and laundry.

The ship served in this capacity during her remaining years, and continued to do so when, in order for the Marine Hospital Service to reflect the organization’s growing responsibilities, it expanded into the Public Health and Marine Hospital Service in 1902, and ten years later when it was renamed the Public Health Service. Congressional legislation broadened the service’s powers and authorized its inspectors to investigate human diseases, sanitation, water supplies, and sewage disposal.

The march of time gradually caught up with Omaha, however, and Ships’ Data U.S. Naval Vessels, 1 January 1914, lists her as “Unserviceable for War Purposes.” The ship was consequently approved for sale on 25 June 1914, and stricken from the Naval Register on 10 July of that year. Omaha was sold for $14,140 to Smith & Bondrow on 17 April 1915.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Capt. John C. Febiger | 12 September 1872 |

| Capt. William K. Mayo | 24 June 1874 |

| Capt. Philip C. Johnson | 13 February 1875 |

| Capt. Edward Simpson | 25 October 1875 |

| Capt. Thomas O. Selfridge Jr. | 16 April 1885 |

| Capt. Frederick V. McNair | 6 January 1888 |

| Capt. Bartlett J. Cromwell | 21 September 1889 |

Mark L. Evans

23 January 2018