Mason II (DE-529)

1944–1945

Newton Henry Mason was born on 24 December 1918, in New York City, N.Y., the son of David W. and Ida K. Mason. He enlisted as a seaman in the U.S. Navy Reserve on 7 November 1940, and then later received appointment as an aviation cadet, A-V (N), USNR, on 10 February 1941. After earning his wings, Ens. Mason went to the Pacific for his first operational assignment. A Grumman F4F Wildcat pilot, Mason initially reported to Fighting Squadron 3 (VF-3) on board the aircraft carrier Saratoga (CV-3). After being torpedoed in January 1942, Saratoga had to undergo extensive repairs and Mason was re-assigned to VF-2 on board Lexington (CV-2).

In May 1942, U.S. and Australian forces moved to repel a Japanese invasion fleet targeting Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, and Tulagi, Solomon Islands—ultimately culminating in the pivotal Battle of the Coral Sea (4–8 May 1942). During the initial stages of the Japanese offensive, on 3 and 4 May, Japanese forces successfully invaded Tulagi, but were harassed by planes from Yorktown (CV-5). American and Japanese carrier forces then made their way to the Coral Sea, where, from 7 to 8 May, they launched multiple devastating airstrikes against each other.

Lexington and her air group were among the U.S. aircraft carriers that participated in the battle. On 8 May 1942, Ens. Mason took off from Lexington for his first and last combat mission. Only a few hours into the action he was shot down while battling a group of Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters from the Japanese aircraft carrier Shōkaku.

For his valiant service during the battle Ens. Mason, was posthumously awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross and a Purple Heart. He is memorialized on the Tablets of the Missing located at Manila American Cemetery, Republic of the Philippines.

II

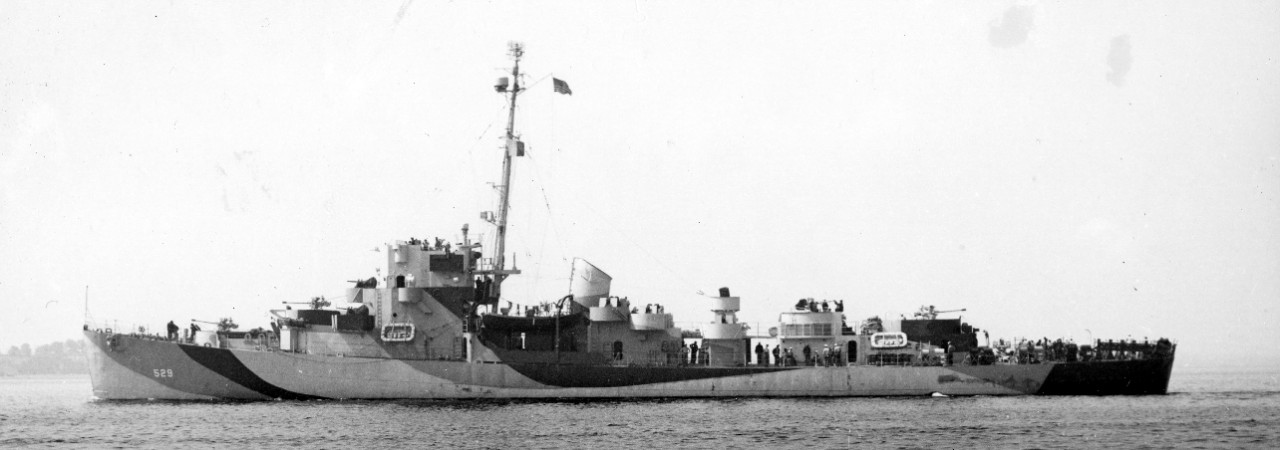

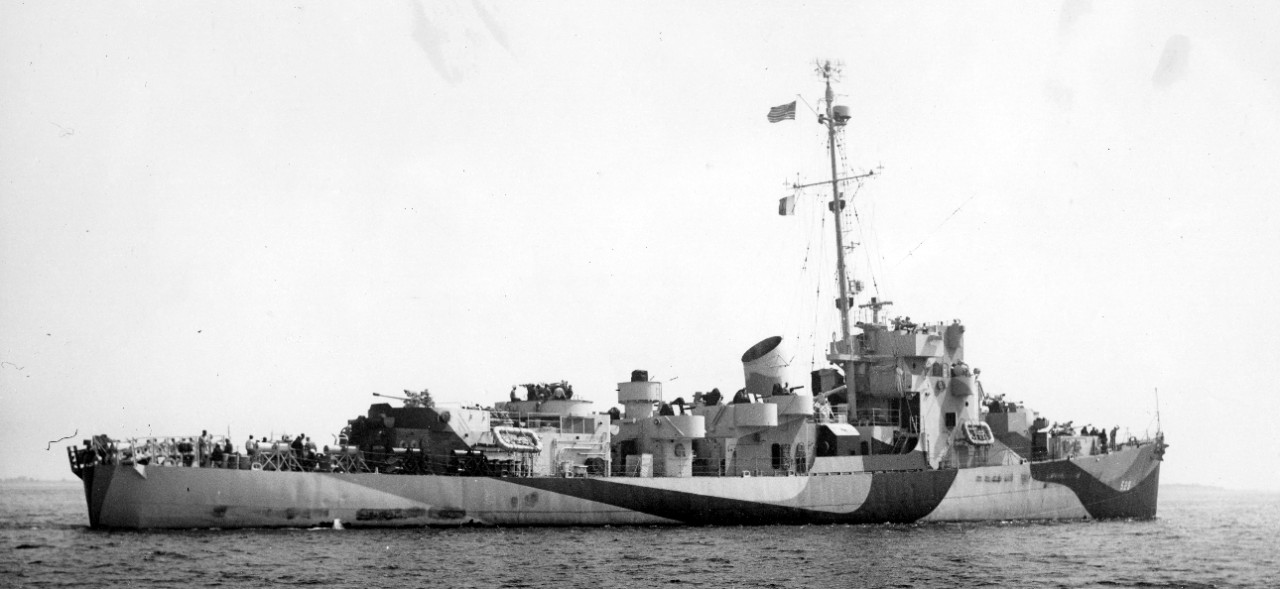

(DE‑529: displacement 1,140; length 289'5"; beam 35'1"; draft 8'3"; speed 21 knots; complement 156; armament 3 3-inch, 4 1.1-inch, 9 20 millimeter, 2 depth charge tracks, 8 depth charge projectors, 1 depth charge projector (hedgehog); class Evarts)

The second Mason (DE‑529) was laid down on 14 October 1943 at Boston, Mass., by the Boston Navy Yard; launched on 17 November 1943; sponsored by Mrs. Ida K. Mason, the mother of the late Ens. Newton H. Mason; and commissioned on 20 March 1944, Lt. Cmdr. William M. Blackford, USNR, in command.

Mason holds a unique distinction among the many American fighting ships that served during the course of the Second World War. Abetted by the passionate advocacy of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Mason became one of only two U.S. warships in the conflict (the other being the submarine chaser PC-1264) that were manned predominantly by African American crew members. Out of a crew of 204, 160 of her sailors were African American. This was a novel occurrence because for the first several years of the war African American sailors throughout the Navy were limited to positions as cooks, stewards and manual laborers. Prior to her commissioning Mason’s crew received their training in a segregated training facility at Camp Robert Smalls, Ill. Early on in their training there they were given poor accommodations and subjected to unequal treatment. However, after becoming fully aware of the situation, Mason’s officers stepped in to get their men better lodging, as well as to demand that they be treated like any other sailors on the base.

From beginning to end, Mason’s crew faced many added challenges. Yet, despite that fact the warship’s inclusion in the fleet also represented a singular opportunity for African American sailors during that era to serve in a broader capacity. This fact was not lost on those who volunteered to serve on Mason. In an oral history interview with Mason veteran SM1C Lorenzo Dufau, a native of New Orleans, La., the ship’s crew was reportedly highly motivated, and in spite of their experiences with racial discrimination they proved eager for an opportunity to actively serve and defend their country. Regarding his own decision to serve on board Mason, S1C Dufau recalled that “If you call yourself a man, you defend your home and country… I felt that if I can get in and make it possible to be helping to protect this place, I would also help open doors for my son.”

Following her commissioning Mason spent several days acquiring stores and spares and then got underway for her first trial run on 31 March 1944. Although the warship was declared “complete by the Navy Yard,” as of 31 March, on the 1st of April, following a brief structural test, Lt. Cmdr. Blackford indicated in the ship’s log that “many items were still incomplete.” Another week passed before Mason was fully ready for sea and on 9 April, she departed from the Peaked Hill Bar Buoy and shaped a course for Great Sound, Bermuda, British West Indies.

Following her arrival in the Bermuda area on 11 April 1944, Mason commenced a rigorous shakedown cruise lasting well into the following month. On 15 May 1944, the escort vessel detached from her shakedown group and headed to Boston at a speed of 18 knots. Arriving on 17 May Mason then began her post-shakedown availability.

On 26 May 1944, Mason got underway from Boston Harbor and set course for Casco Bay, Maine, arriving there early the following day. Shortly thereafter Mason joined Task Group (TG) 23.9 and participated in anti-submarine warfare exercises with Barber (DE-161) and the U.S. Coast Guard gunboat Northland (WPG-49), in the vicinity of Casco Bay. According to Lt. Cmdr. Blackford these exercises were “by far the most educational experienced by this ship since commissioning.”

Mason departed the Casco Bay area in preparation for her first convoy mission on 5 June 1944. Steaming with TG 27.5, which included Stern (DE-187) and O’Neill (DE-188), Mason and her cohorts made their way to Charleston, S.C. At 0802 on 8 June, Mason entered Charleston Harbor and then made her way to the Charleston Navy Yard, where she moored to received provisions and equipment.

After spending nearly, a full week at Charleston, Mason got underway with TG 27.5 escorting convoy CK-3 to Europe. John J. Powers (DE-528) and John M. Bermingham (DE-530) joined company with them prior to their departure from Charleston on 14 June 1944. The convoy anchored at Fort Royal Bay, Bermuda on 20 June, and then continued on their way on the 23rd. Just a few hours before midnight on 26 June, Mason intercepted an “enigma message on 560 kcs,” however, she was unable to get the bearings of the suspected U-Boat due to its short transmission time. Four days later on the 30th a subsequent report was received of a U-boat operating within 50 miles of the convoy and the ship’s company remained on edge.

The U-boat threat passed and on 6 July 1944, Mason sighted Mt. Pico, Horta Roads, Azores, and shortly thereafter the convoy began its approach to the harbor. After finally anchoring at about 2000, Mason commenced a listening and radar watch. She remained moored there for several days, and despite the fact that no one was permitted shore leave or liberty, a shore patrol had to be dispatched on 8 July to “round up some merchant seamen who had gotten ashore in bum boats.”

In the afternoon on 12 July 1944, Mason at last got back underway with “a 17-ship convoy bound for United Kingdom ports.” An unidentified plane “apparently a snooper,” passed over the convoy on 18 July displaying its navigation lights and maneuvering around the area. Mason’s crew manned their battle stations and tracked the aircraft until it eventually disappeared from radar, flying on a course for St. Nazaire, France.

During the early morning hours of 21 July 1944, Lt. Cmdr. Blackford and a number of the ship’s company observed “St. Elmo’s Fire” envelope the ship’s mast and rigging. The glowing ball of light, which has often struck sailors with immense awe is named for St. Erasmus of Formia, the patron saint of sailors. Although St. Elmo’s Fire has long inspired superstition among sailors, it is in actuality a weather phenomenon, in which luminous plasma is created by a corona discharge from a pointed object passing through a strong electric field in the atmosphere, such as during a thunderstorm. This particular episode resulted in Mason’s radios cutting out completely for several minutes. The following day, Mason arrived off the shores of Cornwall, England.

Proceeding through the Irish Sea, on 23 July 1944, Mason arrived off the Mall of Galloway and thence steamed to the Firth of Clyde. After “screening the Clyde section of the convoy,” Mason continued on with Stern to Belfast, Antrim, Northern Ireland, arriving there just a few hours later. After mooring at Pollock Dock in Belfast, Mason began a brief period of routine maintenance while one half the ship’s company was granted liberty. Several of Mason’s African American sailors recalled that their leave in Ireland proved to be one of the best experiences they had during the war, largely because it was one of the few places, they were treated just like regular U.S. sailors.

Rejoining TG 27.5 on 26 July 1944, Mason got underway at 0701 with “all ships proceeding on line of bearing at an interval of three thousand yards,” bound for the East Coast of the United States. On 2 August Mason arrived at the Navy Yard Annex, South Boston, and commenced a 12-day availability, which was later extended by one day in order to calibrate her newly installed radio direction-finding equipment or DAQ.

On 16 August 1944, Mason got underway for Casco Bay. Upon her arrival there she began “scheduled exercises as OCE for three DEs, two DDs and one AO.” These drills included fueling at sea by abeam and astern methods, as well as anti-aircraft firing and night illumination practice. Following a week of training in the area, Mason departed Casco Bay and steamed to Boston where she fueled and provisioned to capacity in anticipation of extended escort duty.

On 28 August 1944, Mason, in company with Jack W. Wilke (DE-800), Earl K. Olsen (DE-765) and Cates (DE-763), took up a position escorting a section of convoy CU-37. A few days later on 30 August, Mason embarked an officer from the destroyer Tillman (DD-641), via whaleboat, for transportation to Casco Bay. On 31 August Mason disembarked her passenger (Capt. Poole) at Portland, Maine, and then proceeded to the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y., where she arrived on 2 September and commenced an eight-day availability. From 10 to 18 September, she re-provisioned and made special preparations for an upcoming trans-Atlantic convoy.

Following some delay due to poor weather in the area, Mason eventually pushed off from the 33rd St. Pier in South Brooklyn, on 19 September 1944. She then joined convoy NY- 119, which consisted largely of a number of U.S. Army tugs, barges and other small craft. Her fellow escorts for the voyage (a part of TG 27.5) included: the oiler Maumee (AO-2), the fleet tug Abnaki (AT-96), O’Toole (DE-527), John J. Powers, John M. Bermingham, and Edgar G. Chase (DE-16). The nature of the convoy (consisting largely of small vessels in tow) made for slow progress, with a majority of ships averaging only 5 knots.

Several days of poor weather further impeded the progress of the convoy’s vulnerable tugs and other small craft. On 23 September 1944, Mason had to pass spare parts to a large tug that went out of operation. A few days later during the early morning hours of the 26th, Mason responded to a distress call from Army tug ST-179, which had capsized while in the tow of the larger tug LT-492. Mason screened subsequent salvage efforts and then continued on with the rest of the convoy.

On 6 October 1944, Mason arrived off Flores Island, Azores, and several ships maneuvered into port for repairs. On 14 October the convoy continued on its way to its primary destination at Falmouth, United Kingdom. Fears, induced by numerous reports German U-boats trailing the convoy were only allayed with the onset of yet another potential peril—bad weather. On 16 October Mason and her cohorts encountered a severe tempest which featured harsh cold winds and mountainous seas. As QM2c Charles Divers recalled, at one point “We went over 70 degrees and I watched the inclinometer and thought, this is it.” The violent pressure of the storm split the ship’s deck plate, which then had to be welded back together by two damage controlmen. As the convoy became hopelessly scattered amid the raging storm, Mason received orders to steam ahead with some of the other faster vessels and make for Falmouth.

“Escorting the advance section of the convoy,” Mason arrived off Falmouth on 18 October 1944. Just as the first of the convoy’s ships began to enter Swift Channel the “barometer began falling rapidly with winds and seas increasing.” As the weather worsened many of the ships began scattering and there became a real danger that some of them would be swept past the harbor entrance. Mason requested the aid of additional escorts, and working with the British boom defense vessel Pretext (Z-284) “it became necessary to lead the section from buoy to buoy,” and then to “run back to the end of the column about seven miles astern to guide in any possible stragglers.” Despite wind gusts reaching 80 knots “all vessels of the advanced section were successfully turned over to the local escort inside the bay by 1645.”

Early in the morning on 19 October 1944, Mason steamed out of Falmouth to search for wrecked barges off the Scilly Isles. She combed the waterways well into the night with negative results, and then the following morning at 0445, Mason abandoned the search after receiving orders to take shelter at Plymouth, U.K. From 21 to 23 October, Mason moored in the Tamar River, Plymouth, awaiting towboat facilities for salvage work. Amid calmer weather on 24 October Mason accompanied by John J. Powers and John M. Bermingham, got underway to “report and recover salvageable barges,” this time assisted by British aircraft. Mason continued the search for several days.

On 25 October 1944, Mason located BCF-3214 but the vessel’s proximity to a nearby minefield delayed salvage efforts. During the dark, early morning hours of 26 October, Mason made radar contact with an unidentified target prompting an immediate call to battle stations. Not indicated in any of the convoy movement reports, Mason closed on the unknown ship to about 4,000 yards and challenged it, without result. Two patterns of star shells however, “brought prompt identification of the ship as the British tanker Vin River,” bound for Barrow. Search efforts came to a close the following day and Mason proceeded in company with John M. Bermingham to Tamar River in order to commence storm repairs while the crew enjoyed some “long awaited liberty.”

Steaming out of Plymouth Gate at 0900 on 7 November 1944, Mason got underway with TG 27.5, escorting convoy NY-119, back to the East Coast via the Azores. On 19 November part of the convoy split off and headed for New York City, while Mason continued on with the others bound for Norfolk, Va. Arriving off the Chesapeake on 22 November Mason then steamed independently to New York, arriving there later that night. The escort vessel then commenced a 12-day availability during which she received a Bearing Indicator for her Sonar Equipment.

On 6 December 1944, Mason loaded ordnance at the Naval Ammunition Depot, Earle, N.J., and then the following morning got underway with Edgar G. Chase to conduct exercises at Casco Bay. Mason arrived at Casco Bay on the 8th and then on the 9th commenced a series of anti-submarine warfare exercises. On 12 December exercises were temporarily cancelled due to some “disagreeable weather,” but then resumed the following day.

“Ready for extended duty,” Mason quit the Casco Bay area on 15 December 1944, and shaped a course for Naval Operating Base (NOB) Norfolk. On the 17th the escort vessel arrived in the Chesapeake Bay and anchored at Norfolk later that same evening. On 18 December Mason steamed to Lynnhaven Roads and anchored to the seaward of the merchant ships of convoy UGS-64. Joined by fellow escorts of Task Force 64: Livermore (DD-429), O’Toole, Andres (DE-45), John M. Bermingham and Edgar G. Chase, Mason got underway with UGS 64 on 19 December bound for Oran, Algeria.

Mason’s journey across the Atlantic in late December 1944 was largely uneventful marked only by some heavy seas, and an occasional school of fish mistaken for a U-boat. However, as she approached Gibraltar on 2 January 1945, some extra precautions were taken after a German submarine was reported in the area. On the 4th the convoy cleared the straits without any issues and, relieved of escort duty, Mason steamed to Oran, mooring at Mers-El-Kébir on 5 January. With her arrival in Oran TF 64 was dissolved and Mason, the destroyer Balch (DD-363), O’Toole, John J. Powers and the patrol frigate Gulfport (PF-20), tasked with escorting GUS-64 back to the U.S., formed TG 60.11.

“Topped off with water and a small amount of provisions,” on 6 January 1945, Mason put back out to sea with her convoy and headed back to the United States. Almost a week into her return voyage, at 0010 on 11 January, Mason made sonar contact with an object, which was initially “evaluated as a non-sub due to mushy echoes, narrow target, lack of bearing and erratic recorder traces.” Five minutes later however, at 0015 another contact developed and “this pip bore such a remarkable resemblance to a periscope seen during training exercises that the decision was made to attack regardless of the previous evaluation.” With all hands at their battle stations, Mason moved at full speed to ram the object while dropping depth charges set at 50 feet.

At 0021 “a heavy shock was felt forward,” and shortly thereafter lookouts reported wreckage floating down both sides of the ship. “Illumination by searchlight revealed plainly that the target was wooden derelict,” probably a barge. The collision caused some severe damage to “the sound gear and pit log.” After providing a damage report Mason, per the order of the task group commander, departed the convoy and steamed independently for Bermuda. While still en route on 14 January 1945, Mason received orders to continue on to the New York Navy Yard for repairs. As of the 16th, however, it became clear that due to heavy fuel consumption and leaking, it would still be necessary to make port in Bermuda.

Just before midnight on 18 January 1945, Mason arrived at Fathom Hole, Bermuda, and then awaited an early morning entry into St. George’s Harbor. At 0840 on 19 January, the escort vessel entered the harbor and fueled to capacity. A local diver then inspected the sound dome and shafts of the vessel, consequently giving her captain “the ok” to continue on to New York. That same evening at 1745, Mason steamed out of St. George’s Harbor and continued on her way to the New York Navy Yard.

Arriving at her destination on 22 January 1945, Mason then underwent a ten-day availability. The escort vessel later weighed anchor on 2 February and headed for the Ammunition Depot to rearm. En route, Mason “experienced considerable difficulty in proceeding through the thick ice in lower New York Bay,” and at one point she lost all of her electrical power due to a “clogging of sea water in the intake strainers.” Upon remedying the issue Mason steamed via Sandy Hook and Gedney Channels for New London, Conn., arriving there the following day.

Upon her arrival at New London, Mason commenced a series of submarine exercises which she participated in a on a daily basis until the evening of 7 February 1945. In preparation for another trans-Atlantic convoy, Mason in company with Gulfport departed New London on 8 February and made her way to Norfolk. Arriving in Virginian waters late on the 9th, Lt. Cmdr. Blackford then “attended pre-sailing conferences for convoy UGS-74,” on the 11th. On 12 February Mason and the other escorts of TG 60.11 put out to sea with the convoy.

After more than a week of hard steaming, on 27 February 1944, Mason made radar landfall on the coast of Morocco. On 1 March she proceeded with the other escorts to Oran and moored at Mers-El-Kébir for a layover period. She briefly ventured out of port with some of the other escort vessels on 6 March in order to conduct anti-submarine and anti-aircraft exercises in local waters. Then on 8 March at 0645, Mason sortied out with GUS-76 bound for “state side ports.” The voyage back across the Atlantic was relatively calm and on 23 March, just off Ambrose Light, Lower New York Bay, Mason detached from the convoy and proceeded to the Earle Depot to offload her depth charges and other ammunition. On 24 March Mason arrived at the Navy Yard, Bayonne, N.J., and commenced a ten-day availability.

On 4 April 1945, several civilian experts from General Motors and Allis-Chalmers came on board Mason, and the warship then got underway for a training period near New London. Upon her arrival Mason began carrying out sonar exercises, fighter director training with naval planes and anti-submarine training. On 5 April she participated in exercises with the submarine S-20 (SS-125).

While conducting exercises during this period U.S. Navy photographers from the Bureau of Aeronautics came on board and took pictures and video footage of Mason’s crew and operations for a “forthcoming Navy motion picture titled ‘The Negro Sailor.’” According to Lt. Cmdr. Blackford the “ship’s officers and company gave them every possible assistance and cooperation.” The footage was subsequently used in a 1945 U.S. Navy documentary short film directed by Henry Levin and aired by All-American News.

With her exercises concluded, Mason steamed to NOB Norfolk, arriving there on 10 April 1945. On the 14th the escort vessel got underway for the convoy anchorage at Lynnhaven Roads, where shortly after her arrival she passed mail to a number of the other escort ships. Later that evening Mason took up patrol station 5 on the starboard flank of convoy UGS-86 and got underway for the Mediterranean Sea.

Mason reached the straits of Gibraltar on 28 April 1945, and then the following day moored at Mers-el-Kébir where half the crew was granted shore liberty. For several days in May, Mason, John J. Powers and O’Toole trained in local waters with a French submarine before finally getting back underway again for the United States on the 7th, to escort convoy GUS-88. Additional escorts included: destroyers Balch and McCook (DD-496), and the frigates El Paso (PF-41) and Eugene (PF-40).

Following a lengthy voyage, on 23 May 1945, Mason was relieved of escort duty at the Harbor Entrance Control Post at Cape Henry, Virginia. She then steamed directly to New York City where she moored at the 35th Street Pier in Brooklyn. Upon her arrival, Mason commenced a 15-day availability period and shortly thereafter on 12 June Lt. Cmdr. Blackford was relieved of command by Lt. Cmdr. Norman H. Meyer. As Lt. Cmdr. Blackford had been a steadfast advocate of his crew, he was widely regarded by them and his departure was keenly felt.

Well into July 1945, Mason conducted local operations along the East Coast. On 14 June she underwent an additional week of upkeep in New Jersey and then on 26 June moored overnight at Tompkinsville, Staten Island, N.Y., to weather a hurricane then bearing down on the area. Between 27 June and the 5 July, Mason remained in the vicinity of New York, but conducted several depth charges tests in nearby waters. On 6 July Mason steamed to Casco Bay and from the 8th to the 17th she participated in ship handling drills and tactical maneuvers.

Late in the afternoon on 17 July 1945, Mason received notification to cease her training operations and get underway with John J. Powers and O’Toole for Miami, Fla. Due to a slight adjustment in her orders while still en route, Mason altered course and proceeded independently to Port Everglades, Fla. Following her arrival there she spent the next week participating in anti-submarine counter measures as a part of TG 28.4.

Underway for Miami on 28 July 1945, Mason served as a school ship for the Naval Training Center, Miami, well into the next month. On 18 August Mason steamed north to New London, and then just a day after arriving there on the 26th she got back underway for Bermuda to be fitted for long range underwater signaling testing. Mason arrived at NOB Bermuda, on 30 August and remained there through the first week of September.

On 8 September 1945, Mason got underway for Charleston, S.C., and arrived there two days later. The escort vessel was then decommissioned the following month, on 12 October.

Mason was stricken from the Naval Vessel register on 1 November 1945.

The ex-Mason was sold and delivered at Charleston to Thomas Harris of Barber, N.J., on 18 March 1947, for scrapping.

When one contemplates the history of the U.S. Navy’s operations in World War II, Mason certainly has a unique legacy. Despite her crew’s heroic contributions to the war effort, particularly during their operations with convoy NY-119 during the fall of 1944, Mason’s brave sailors were initially largely ignored and later forgotten. Even Lt. Cmdr. Blackford’s official recommendation that commendations be given to the crew fell on deaf ears. It wasn’t until the 1990s that Secretary of the Navy John Dalton (1993–1998), recognizing that Mason’s story was “an important part of Navy history,” awarded the ship’s surviving veterans with some long overdue commendations. Yet, in spite of all the crew’s struggles during and after the war, the words of Mason veteran S1C Dufau shine through as an enduring testament of the character of the Mason sailors “I would do it all over again,” he said, and “I never did develop any bitterness or hatred or anger toward anyone… Hate is a sickness and it will destroy you.”

Mason has been the subject of a book and several movies including: the feature film Proud (2004) and the documentary and book Proudly We Served: The Men of the USS Mason by Mary Pat Kelly.

| Commanding Officers | Dates Assumed Command |

| Lt. Cmdr. William M. Blackford, USNR | 20 March 1944 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Norman H. Meyer | 12 June 1945 |

| Lt. John C. Phillips, USNR | 20 September 1945 |

Jeremiah D. Foster

29 June 2020