Maine II (Battleship No. 10)

1902–1920

Maine was admitted to the Union as the 23rd State on 15 March 1820. A mysterious explosion ripped apart the second class battleship Maine, Capt. Charles D. Sigsbee in command, on the night of 20 February 1898, wrecking the ship and killing 260 men. A court of inquiry convened the following month and proved unable to obtain evidence associating the destruction of the battleship with any person or persons, but the disaster so inflamed U.S. public opinion that the loss of the ship became one of the causes of the Spanish-American War.

In barely three months following the loss of the first Maine, on 2 May 1898, Congress passed an authorization act “for the purpose of further increasing the naval establishment,” which included the authorization for a contract for the construction of “three seagoing coast-line battle ships carrying the heaviest armor and most powerful ordnance upon a displacement of about eleven thousand tons, to have the highest practicable speed for vessels of their class, and to cost, exclusive of armor and armament, not exceeding three million dollars each, one of said battle ships to be named the Maine…”

II

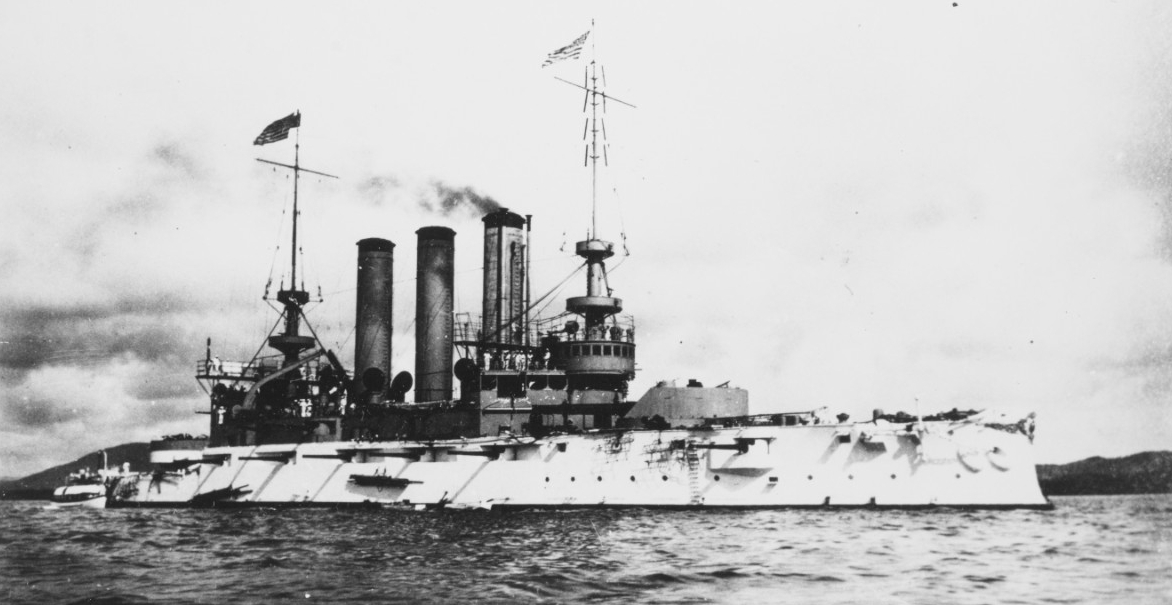

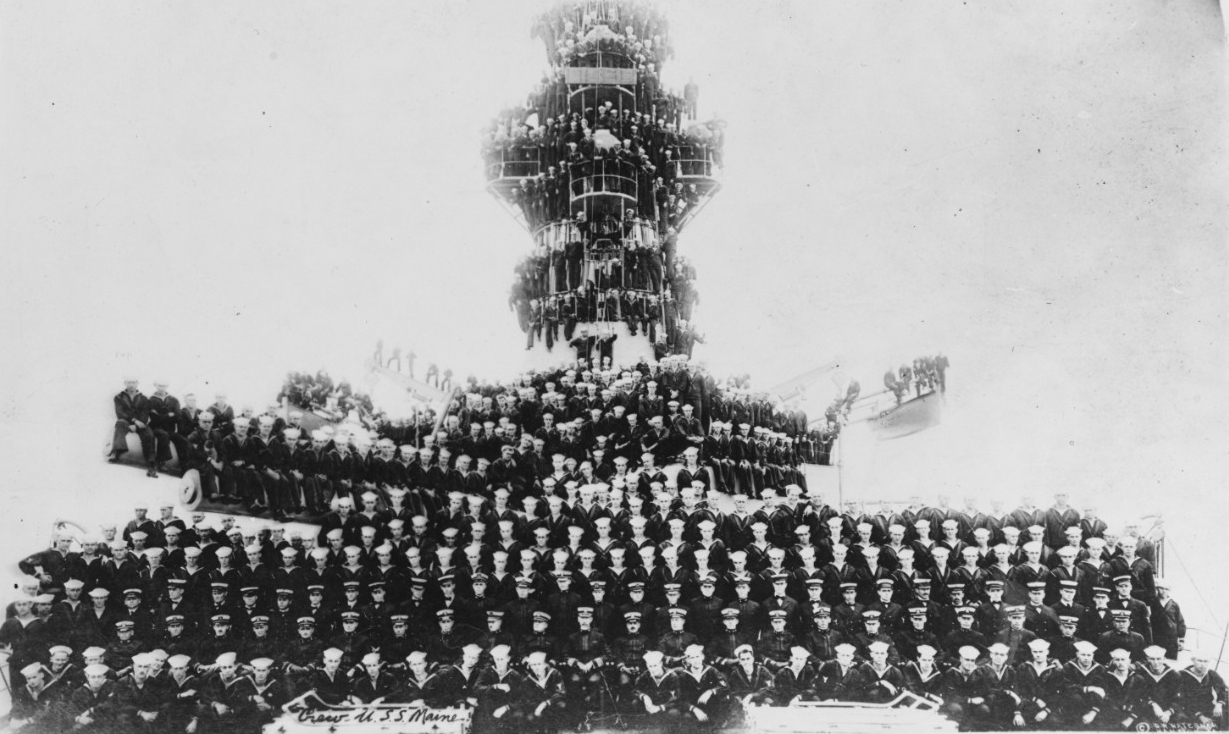

(Battleship No. 10: displacement 12,846; length 393'11"; beam 72'3"; draft 24'4"; speed 18 knots; complement 648; armament 4 12-inch, 16 6-inch, 6 3-inch, 8 Hotchkiss 3‑pounder rapid-fire guns, 2 Hotchkiss 1-pounder rapid-fire, 4 Maxim-Nordenfelt 1 pounder semi-automatic, 2 M1895 Colt-Browning machine guns [landing force], 2 18-inch torpedo tubes; class Maine)

The second Maine (Battleship No. 10) was laid down by William Cramp & Sons, Philadelphia, Pa., 15 February 1899, a year to the day after the destruction of the first Maine; launched on 27 July 1901; sponsored by Miss Mary P. Anderson (née Preble), daughter of William and Alice P. Anderson of Portland, Maine, and great granddaughter of Commodore Edward Preble; and commissioned on 29 December 1902, Capt. Eugene H.C. Leutze in command.

The ship’s main battery of 12-inch guns fired their rounds at a velocity which gave them greater penetration than the heavier 13-inch shells of the previous Illinois (Battleship No. 7) class vessels. Maine performed well during her acceptance trials, and the inspectors noted a turning circle of 325 yards while she made 18.2 knots. “The estimated diameter of the turning circles at full speed ahead,” her trial board reported, “with full starboard or port helms, was remarkably small and showed maneuvering qualities of the highest order.”

The ship handled poorly in foul weather, however, and often shipped water in heavy seas. Whenever Maine steamed before a quartering sea of any size, water washed over her after weather deck. The gun crewmen gamely manned Turret II -- the after twin 12-inch gun turret -- despite battling the sea but flying spray often prevented them from using the turret sights, a telling tactical problem in the days before director-controlled firing. Secretary of the Navy William H. Moody observed in his annual report for 1903 that some of the ship’s 6-inch guns emplacements presented problems “due to the very great energy of their new high-power guns,” but added that the “matters have been or are being rectified, and no further difficulty is anticipated.”

In addition, Maine’s ventilation proved inadequate, as it did in her sister ships, Missouri (Battleship No. 11) and Ohio (Battleship No. 12). Some compartments became so overheated as to preclude safe operations, and Missouri’s preliminary trial board recorded that the temperature rose to 147°F in some of her coal bunkers, observing that “it would appear doubtful whether coal can be safely carried in these bunkers.” Maine furthermore burned coal at an excessive rate, a problem that often frustrated naval planners when they attempted to deploy the ship (see 16 December 1907).

Following her commissioning, Maine anchored off Reedy Island, Del. (16–17 February 1903), and then (18–24 February) set out to join the battleship squadron at Hampton Roads, Va. Maine joined her consorts and turned southward to carry out a series of problems (training exercises) that included firing at a target off Culebra Island, P.R. (24 February–10 April). The ship completed repairs at San Juan on the 5th and returned to Hampton Roads. Maine accomplished some repairs at League Island, Pa. (19 April–5 May), and next more extensive work at Cramp’s shipyard.

The ship then turned south and plunged into a burgeoning crisis in Panama. The United States sought the exclusive right to build and control an interoceanic canal across the Panamanian Isthmus -- under Colombian rule -- and during the autumn of 1903, rising tensions threatened to engulf the region in conflict. The U.S. dispatched ships to the area and at 5:30 p.m. on 2 November Nashville (Gunboat No. 7), Cmdr. John Hubbard in command, anchored at Colón to protect Americans there. Just before midnight Colombian troopship Cartagena entered the roadstead and anchored near the U.S. gunboat, and began disembarking 474 Colombian soldiers during the forenoon watch. Rumors circulated that the troops intended to march on Panama City to ensure order, but at 6:00 p.m. on 3 November, Panamanians seeking independence rose against the Colombians. Hubbard landed a detachment of marines, Lt. Cmdr. Horace M. Witzel in command, shortly after noon the following day, and they established positions at the railroad office, blocking the Colombian soldiers from taking a train into the city. The marines returned to the ship overnight, but some landed again the following morning and reoccupied their positions.

More U.S. ships reached the area and often landed bluejackets and marines during the succeeding days, including Maine, protected cruiser Atlanta, Olympia (Cruiser No. 6), torpedo vessel tender Dixie, transport Prairie, and armed yacht Mayflower, which operated off Panama’s Atlantic coast, and protected cruiser Boston, Marblehead (Cruiser No. 11), Wyoming (Monitor No. 10), and Concord (Gunboat No. 3), which steamed off the embattled country’s Pacific coast. Maine eventually came about and returned home. The United States meanwhile recognized Panama’s independence on 6 November 1903, and on the 18th, Secretary of State John M. Hay and Philippe-Jean-Bunau-Varilla, the Panamanian ambassador to the U.S., concluded a treaty for the construction of the canal. The Americans gained sovereign rights to a ten-mile-wide canal zone across the country, for which they paid a lump sum of $10 million and an annuity of $250,000, and agreed to maintain Panama’s independence. They paid an additional $25 million to the Colombians upon approval of the Treaty of Bogotá in February 1921.

President Theodore Roosevelt intended to project U.S. naval power into European waters, especially within the Mediterranean Sea, and directed the Navy to deploy several squadrons across the Atlantic during the winter of 1903 and 1904. The ships gathered and trained in the Caribbean, and on 9 May 1904 began coaling at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. The vessels mostly operated with fouled bottoms and required work in shipyards, but the Navy directed Rear Adm. Albert S. Barker, Commander-in-Chief, North Atlantic Fleet, to deploy the North Atlantic Battleship Squadron, consisting of Kearsarge (Battleship No. 5) -- his flagship -- Alabama (Battleship No. 8), Illinois, Iowa (Battleship No. 4), Maine, and Missouri, across the Atlantic to Lisbon, Portugal. Illinois, Maine, and Missouri suffered accidents, however, that delayed their arrival, halving Barker’s strength.

Missouri’s steering gear broke down while the fleet carried out target practice on 11 March 1904, and Illinois and Missouri collided. Ill fortune hounded Missouri and while she conducted target practice on 13 April, an explosion in the port 12-inch gun in her after turret killed 36 men. Some of the survivors swiftly prevented the fire from spreading to her magazines and saved the ship, and three men received the Medal of Honor for braving the flames to extinguish the blaze — Chief Gunner Robert E. Cox, GMC Mons Monssen, and GM1c Charles S. Schepke. Missouri completed repairs at Newport News, Va. Naval investigators worked tirelessly at the Washington Navy Yard, D.C., and devised a method to inject a jet of compressed air into a gun’s bore as its breech lock began to unscrew.

Moroccan Sharif Mulai A. er Raisuni, known as “The Raisuli” to most Americans, kidnapped a man and a boy he erroneously believed to be U.S. citizens, Ion H. Perdicaris and Cromwell O. Varley, from Perdicaris’ villa in Tangier, Morocco, on 18 May 1904. The British, French, Germans, and Spanish all vied for control of Morocco, alternatively presenting extravagant gifts to Sultan Abdelaziz, in the hope of gaining coaling concessions for their ships. Raisuni resented the foreigners’ influence and apparently sought to embarrass the sultan, demanding a ransom for the safe return on his hostages. “Situation serious,” U.S. Consul Gen. Samuel R. Gummeré telegraphed to the State Department the following day, “Request man-of-war to enforce demands.”

The U.S. initially sent the South Atlantic Squadron, Rear Adm. French E. Chadwick in command, to Tangier to compel the release of the hostages. Chadwick broke his flag in Brooklyn and the squadron also consisted of Castine (Gunboat No. 6), Machias (Gunboat No. 5), and Marietta (Gunboat No. 15). Rear Adm. Theodore F. Jewell in the meantime relieved Rear Adm. Charles S. Cotton in command of the European Squadron, and received orders to reinforce Chadwick. Jewell directed the squadron to set course for Tangier, and Olympia (Cruiser No. 6), Baltimore (Cruiser No. 3), and Cleveland (Cruiser No. 19) reached that port on the first of the month, raising the number of U.S. warships there to seven.

Kearsarge led Maine and the other battleships of the squadron to Lisbon, where they entertained King and Queen Carlos I and Amélie and members of the court on 11 June. The presence of Barker’s battleships anchored in the Tagus roused Portuguese fears of U.S. expansionism, and the Navy instructed the admiral to lay off Lisbon until 16 June, but extended his stay for two days. Their time at that port proved less arduous than feared as the admiral and his officers made the rounds of repeated soirees, Barker diplomatically observing that the queen so “charmed” him that he did not notice whether or not she wore jewels. The admiral added that he and his men “were pretty well tired out when all was over” before they set out for Gibraltar. Following a flurry of negotiations Raisuni received the ransom and returned Perdicaris and Varley on 21 June, and on 27 June the ships came about. The motion picture The Wind and the Lion, released in 1975, dramatizes the incident.

The Navy originally planned to send the South Atlantic Squadron into the Mediterranean but instead dispatched the squadron down the west coast of Africa. The European Squadron spent Independence Day and some days afterward coaling and taking on stores at Gibraltar, where Illinois and Mayflower joined them, and Jewell then took them into the Mediterranean to Trieste in Austria-Hungary. Barker meanwhile deployed his ships into the Mediterranean, Missouri having been delayed by repairs after the collision with Illinois and following the squadron.

Beginning in September 1902, the U.S. Legation at Constantinople [Istanbul] had addressed a note to Ottoman Turkish Sultan Abdul Hamid II requesting that the Sublime Porte grant the same rights and privileges to American educational, charitable, and religious institutions that the Turks granted to a number of the European powers, basing the demand upon the favored-nation clause of the treaty between the U.S. and the Ottoman Empire. The sultan and his representatives repeatedly avoided the issue, however, and in April 1904, the U.S. Minister to Turkey, John G.A. Leishman, reported that the Turks finally refused the request on the grounds that “in regard to the schools and religious institutions, no difficulty being raised on their behalf, there is no reason for their confirmation.” Both governments alternatively postured, and in May Secretary Hay wrote to Leishman that “an imposing naval force will move in the direction of Turkey. You ought to be able to make some judicious use of this fleet in your negotiations within committing the Government to any action”.

The Americans selected Athens, Greece, as a strategic port that brought their ships within a day’s passage of the Dardanelles or Smyrna [Izmir] without making their actions too obvious — and avoiding insulting the sultan. Kearsarge, Alabama, Iowa, and Maine consequently anchored in Phaleron Bay at Piraeus, near Athens (30 June–6 July 1904). Missouri joined them on 3 July, and the American officers made the rounds of their Greek counterparts, and received King George I, Prince Andrew, and Princess Alice on board the flagship on the 4th of July. A number of European diplomats and journalists expressed their concern about the possibility of the crisis escalating. The Russians, in particular, considered the Turks to fall within their sphere of influence and their Ambassador to the U.S., Count Arthur P.N. Cassini, protested the battleships’ arrival. Barker nonetheless followed the visit by exercising the ships in the Aegean Sea, but their departure from port backfired when the sultan cancelled an audience with Leishman on 8 July. Overnight (8–9 July) the battleships stopped briefly at Corfu in the Ionian Islands and the following day entered the Adriatic Sea, where they made port at Trieste (12–24 July). Baltimore, Cleveland, Olympia, and Mayflower joined them from Gibraltar. While there typhoid fever broke out among Kearsarge’s crew, which apparently began during her short-lived sojourn at Athens, and a number of men of the ship’s company convalesced at a hospital ashore.

The European Squadron rendezvoused with Illinois, which had steamed from Gibraltar, and thus reached Trieste a day behind Barker. The fleet then separated again, and the cruisers sailed to Corfu, while Barker signaled “Good Bye” to them and the battleships rounded the Istrian Peninsula and visited Fiume (25–30 July 1904). The absence of the fleet apparently emboldened the Turks and they twice more refused to grant Leishman an audience, both times scarcely hiding their disdain. The Americans grew exasperated, and on 16 July the State Department instructed Leishman to inform Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs Ahmet T. Pasha that it “failed to understand the delay in according him [Leishman] the treatment due to the friendly relations of the two countries”, and to demand an appointment at a fixed time and date. The acrimonious tone of these communiqués carried an implicit threat and on 29 July Leishman conferred with the sultan, who told him he would reply on the school question within four days. The State Department decided to play a strong hand, however, and informed the minister that Barker, who took his battleships through the Strait of Messina on 2 August and six days later back to Gibraltar, would be directed to hold his squadron “in readiness subject to orders.” Jewell brought his cruisers to Villefranche, France, where he received similar messages (3–7 August).

Roosevelt meanwhile on 5 August 1904 impatiently gathered the cabinet in a special session and ordered Jewell to deploy the European Squadron to Smyrna, and directed Barker to continue to maintain his battleships at Gibraltar. Leishman cabled Hay from Pera [Beyoğlu — a district in Constantinople] on 8 August, noting that the Turks had not replied or apologized, and recommending that “unless strong measures are adopted, matters may continue to drag along indefinitely.” Hay responded that Jewell and his ships steamed en route and would reach Smyrna “in a few days,” instructed him to obtain a satisfactory answer from the Turks before the fleet arrived, but added that if the Ottomans failed to “grant the moderate and reasonable requests of this Government”, then Leishman was to take an indefinite leave and depart on board one of Barker’s ships. These types of actions typically presaged fighting, and tensions correspondingly rose, and Leishman pointedly observed that the Turks preferred to negotiate the issue without confronting the fleet. When Hay returned from a meeting with Roosevelt that day, he found Turkish Minister to the United States Chekib Bey filled with “great perturbation about the fleet.” Hay attempted to calm Bey but added that the crisis arose largely because of Turkish intransigence. Olympia, Baltimore, and Cleveland visited Smyrna (12–15 August) and the Turks finally capitulated to the Americans’ demands. Barker in the meantime (8–13 August) waited at Gibraltar and then came about for U.S. waters, refueling and victualing at Horta at Fayal in the Azores (18–20 August) and returning to Menemsha Bight on 29 August. Jewell subsequently followed, concluding the momentous naval deployment to European waters.

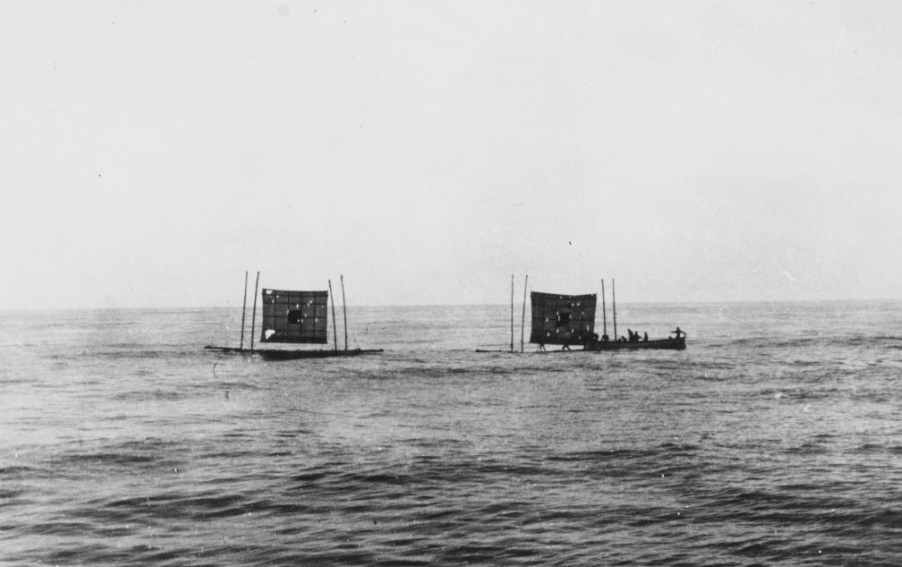

Alabama, Kearsarge, Maine, and Missouri trained at times (29 August–17 September) off Newport, R.I., and Maine shot at targets off Menemsha Bight and Nomans Land, a tiny island located several miles to the southwest of Martha’s Vineyard, carried out torpedo practice, and ran full boiler trials. Maine then waited at Tompkinsville until the 22nd, when a berth became vacant at Boston Navy Yard so that she could complete an overhaul (23 September 1904–27 January 1905).

Maine left the yard and called at Portland (28–29 January 1905), where the Maine Chapters of the Daughters of the American Revolution presented a banner to the battlewagon. The women embroidered the banner by hand on heavy, white corded silk, and it bore the arms of the state in colors. A graceful scroll beneath the insignia of the society, which was done in colors under the central design, bore the words, “Presented by D.A.R. of Maine.”

The battleship accomplished additional repairs at New York Navy Yard (31 January–26 February 1905) and then (4 March–2 May) repeated her winter sojourn southward and charted southerly courses to the Caribbean. Maine took part in fleet maneuvers off Guantánamo Bay (4–22 March), lay to at Pensacola, Fla. (27 March–8 April) while awaiting orders, and on 31 March Rear Adm. Robley D. Evans, Commander in Chief, North Atlantic Fleet, wore his flag in Maine when she relieved Kearsarge as the flagship. The ship fired at the target range off Pensacola (18–22 April), before she returned to Hampton Roads. The man-of-war carried out a series of turning trials and tactical evolutions and maneuvers that included her tactical diameter off the Southern Drill Grounds (15–19 and 23–26 May, and 31 May–3 June), breaking her schedule between each cycle to return to Hampton Roads. Following those maneuvers she lay to at Tompkinsville (8–10 June) before (10–28 June) completing repairs and upkeep in dry dock at New York Navy Yard.

Maine spent the rest of the summer engaged in various evolutions during passage between New England ports: Provincetown, Mass. (29 June–12 July, 15–16 August, 29 August–11 September, and 29–30 September 1905); Newport (13–19 July and 19–25 August); North River, N.Y. (27 July–1 August and 1–2 October); Bar Harbor, Maine (3–11 August); Portland (11–15 August); Narragansett Pier, R.I. (18–19 August); Watch Hill, R.I. (25–28 August); and the target range off Cape Cod (11–29 September).

The ship returned to Hampton Roads to prepare (13–30 October 1905) for the arrival of British Adm. Prince Louis Alexander of Battenberg, who broke his flag in armored cruiser Drake, as he led five other armored cruisers of the Royal Navy’s Atlantic Fleet, Second Cruiser Squadron -- Bedford, Berwick, Cornwall, Cumberland, and Essex -- on a goodwill voyage along the east coast. Maine sailed as one of the ships that welcomed the Prince during his visit to the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md. (30 October–7 November), and then (20 November 1905–4 January 1906) completed repairs in dry dock at New York Navy Yard.

The New Year opened inauspiciously for Maine when Rear Adm. Evans took five battleships from New York to sea, bound for Hampton Roads, at 11:15 a.m. on 7 January 1906. Evans led the column in his flagship Maine, displaying the signal “Follow the flag,” and followed (in order) by Kentucky (Battleship No. 6), Kearsarge, Alabama (Battleship No. 8), and Illinois (Battleship No. 7). Rear Adm. Charles H. Davis, the divisional commander, flew his flag in Alabama. The fleet proceeded at a speed of seven to eight knots but battled strong wind and high tide eddies that swung Kentucky nearly a half mile off the main channel, and Kearsarge, which followed at a 400 yard interval, to the westward. Kentucky lowered her speed and struggled for a few minutes, but at about noon went aground in nearly ten feet of mud off the northwest point of the East Bank, approximately a mile and a half south of Norton’s Island and two miles east of West Bank Light.

Kearsarge attempted to veer to the eastward to avoid her sister but vainly fought the heavy wind and tide and ran aground in order to avoid colliding with Kentucky. Alabama steamed about 800 yards from Kentucky but had way on and slammed into Kentucky on her starboard quarter, seriously damaging Kentucky and tearing a large hole in her own bow. The impact tore away Kentucky’s starboard quarter rail and heavy steel davits, and sliced the captain’s gig in two. Alabama’s collision buckled a number of Kentucky’s plates from the waterline to the superstructure, and most likely damaged her steering gear. The shock ripped open a 15-foot gash in Alabama’s port bow above the waterline, dented plates, and tore off most of the port rail and some davits. The ships miraculously did not report serious casualties.

Illinois overcame the tide, turned into the main channel, and avoided her companions. Alabama continued to the Southwest Split, where she came about and drew alongside Kentucky to render assistance. The distressed ships sent a plea for help by wireless telegraph to Rear Adm. Joseph B. Coghlan, the commandant of the nearby navy yard, who dispatched tugs Apache, Powhatan, and Uncas. The trio reached the scene by about 2 p.m., but Kearsarge and Kentucky freed themselves without the tugs’ help and rendezvoused with Maine, which had reached the area off Sandy Hook. Evans ordered Kentucky detached to return to the navy yard for repairs, Alabama made temporary repairs, and at 5:25 p.m. Alabama, Illinois, Kearsarge, and Maine resumed their voyage.

“These conditions explain the whole situation,” Rear Adm. Davis explained concerning the weather to journalists on board Alabama shortly after the accident, “There is hardly any comment to be made. Such accidents always are likely under conditions such as we had today in a narrow channel.”

Kentucky returned first to Tompkinsville, where a diver examined her hull and ascertained the extent of the damage, and then (8–21 January 1906) completed repairs at New York Navy Yard. Maine continued on and trained with the fleet in the Caribbean (8 January–28 April). The ship operated off Culebra Island until 6 February, and then (8–14 February) visited Port of Spain, Trinidad. Following that port call, Maine resumed training off Guantánamo Bay (19 February–3 March), next (1–15 April) fired at the target range off Cape Cruz, Cuba, and carried out full power trials in company with Kearsarge, Kentucky, and Missouri off Guantánamo Bay (16–28 April). The four battleships returned to Tompkinsville, and Maine and Missouri then (4 May–4 June) detached and visited 79th Street on the North River. Maine set out for her usual summer training off Provincetown (5–6 June) and Rockport, Mass. (6–9 June), and then came about for Tompkinsville and repairs at New York Navy Yard through 14 July.

The ship rejoined the fleet and resumed training off Rockport (16–30 July and 9–18 August 1906), gave her crewmen a welcome liberty call at New York (19–26 August), and then (29–30 August) participated in ceremonies in connection with the unveiling of a monument to Quartermaster William Conway at Camden, Maine. The memorial honored Conway’s “sturdy loyalty” for refusing to haul down the Stars and Stripes when the Confederates seized Pensacola Navy Yard on 12 January 1861.

Maine hove to off Smithtown Bay on Long Island Sound, N.Y., while she prepared (1–2 September 1906) for President Roosevelt to review the fleet off Oyster Bay on the sound (2–4 September — the chief executive did so on the 3rd). “LOW CLOUDS AND FOG MAR BEAUTY OF SPECTACLE” The Washington Times headlined that day. The newspaper nonetheless observed that the fleet presented an “imposing array” of 94 ships — 46 battleships and cruisers, 12 torpedo boats, three submarines, and 33 “picket boats,” manned by 16,036 men (811 officers and 15,225 seamen and marines).

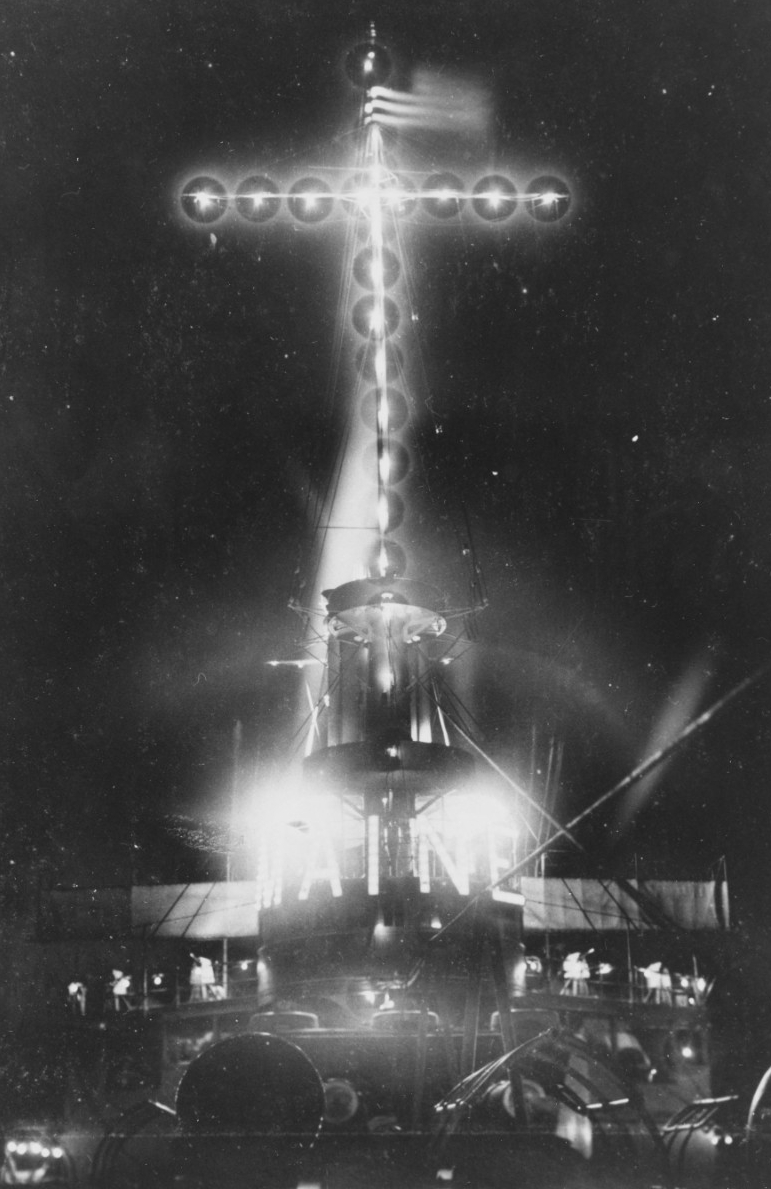

At 8:00 a.m. the fleet “dressed ship” as every vessel broke out clouds and billows of multi-colored bunting from stem to stern. Excursion vessels set out with thousands of visitors from New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island ports to take part in the celebration, but security measures prohibited them from entering the “lines,” and from a distance the fog blanketed the area and prevented most of them from clearly viewing the proceedings. Presidential yacht Mayflower ran up the pennant of the President of the United States at 10:45 a.m., and shortly thereafter, the chief executive and an entourage that included Secretary of the Navy Charles J. Bonaparte set out on board the vessel to review the ships. As they rounded the lighthouse at the point, Rear Adm. Evans, who led the fleet from on board Maine, directed her to begin firing. Upon Maine’s booming signal, dozens of guns suddenly lit up the fog as they cracked out their 21-gun salutes. “The rending din,” the newspaper elaborated, “outrivaled the thunder that accompanied the storm of the early morning before daybreak.”

Following the chief executive’s review, Maine turned northward and operated off Bar Harbor and Provincetown (6–23 and 24–27 September 1906, respectively). Competitive festivities marked both port calls, and on the 18th the ship took part in boat races during Bar Harbor’s Water Festival, and some of her swifter men ran in a track meet at Provincetown. Maine set out for battle practice and tactics in the North Atlantic and shot at targets on the range in Cape Cod Bay (27 September–3 October), and lay to off Provincetown (3–15 October).

A crisis meanwhile loomed to the south. Cuban liberals led a revolt against that country’s President T. Estrada Palma in August 1906. Both sides requested U.S. support, and President Roosevelt directed the War Department and the Navy Department to dispatch ships and troops to protect Americans caught in the conflict, actions that gave rise to the second U.S. occupation of Cuba. Three marine battalions sailed on board Minneapolis (Cruiser No. 13), Newark (Cruiser No. 1), and Tacoma (Cruiser No. 18) on 18, 17, and 16 September, respectively. Kentucky lay off Provincetown on 25 September while the ship prepared for target practice when she received orders to embark marine guards from Kearsarge, Maine, and Missouri, join Indiana (Battleship No. 1), and make speed for Cuban waters. Indiana and Kentucky brought a total of 804 marines on board, steamed southward, and reached Havana on 1 October.

The crisis continued and two additional marine battalions set out for Cuba on board battleship Texas, Brooklyn (Cruiser No. 3), and transport Prairie on 1, 2, and 1 October 1906, respectively. Their arrival raised the number of marines available for the landing force to 2,892 men (97 officers and 2,795 enlisted marines), which formed the First Provisional Brigade, Col. Littleton W.T. Waller, USMC, in command. The marines served under naval jurisdiction, but the confrontation gradually lessened and some of them returned to their various ships and stations. The Navy disbanded the brigade on 1 November, and formed the First Provisional Regiment to continue operations as part of the Army of Cuban Pacification, which the regiment did until it returned to the United States on 23 January 1909.

“It was owing in large part to the General Board,” President Roosevelt wrote in a message to Congress on 3 December 1906, “that the Navy was able at the outset to meet the Cuban crisis with such instant efficiency; ship after ship appearing on the shortest notice at any threatened point, while the Marine Corps in particular performed indispensable service.”

Maine detached many of her marines but otherwise missed deploying to the crisis because she completed repairs at New York Navy Yard (18 October–28 December 1906). The ship wrapped-up the yard work and rejoined her consorts at Hampton Roads just before the New Year, and soon (2 January–15 April 1907) set her bow southward for fleet maneuvers in the Caribbean. The ship worked in the waters off Guantánamo Bay through 10 February, called at Ponce, P.R. (12–15 February), and shot at targets off Guantánamo Bay before returning to Hampton Roads. There she participated (15 April–14 May) in a portion of the Jamestown Exposition, commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown Colony, held at Sewell’s Point, Hampton Roads. The battleship broke her stay to tackle some repairs while at New York Navy Yard (15–23 May) and then (24 May–5 June) at League Island, and returned to Hampton Roads in time for a Presidential Naval Review from Fort Monroe, Va., on 10 June. Maine intermittingly trained off the Southern Drill Grounds (19–22 and 26–28 June) and returned to Hampton Roads, and then (4–24 August) visited New York City and trained in New England waters off Rockport (7–13 September), shot at targets off Barnstable, Mass. (13 September–2 October), and called at Provincetown (2–5 October).

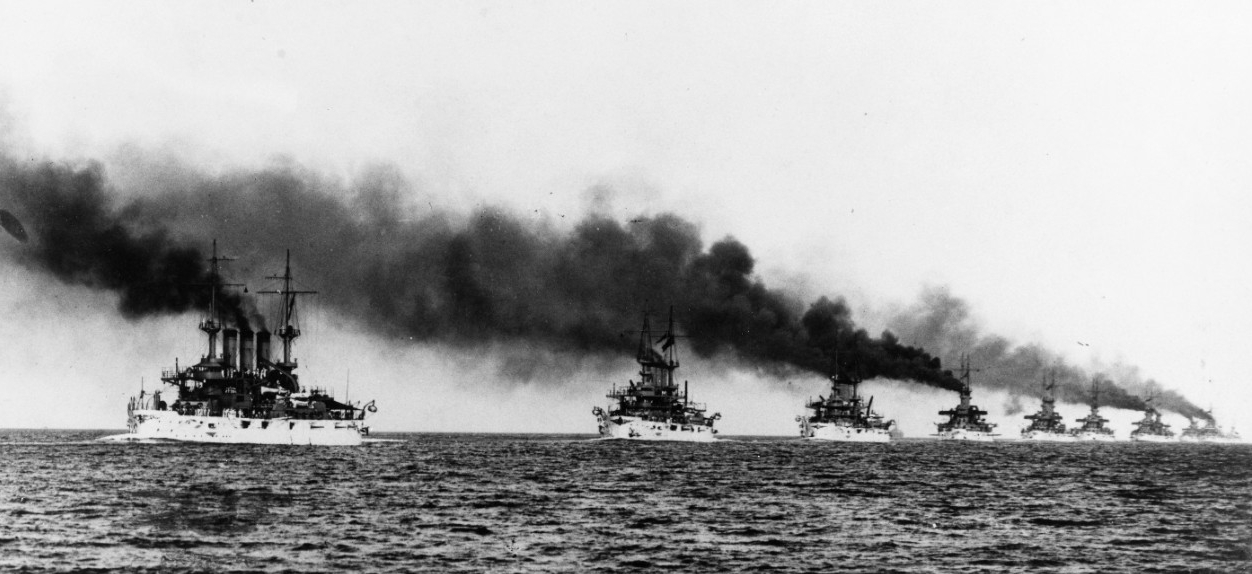

The ship came about from those maneuvers and accomplished repairs at League Island (7 October–8 December 1907) to prepare for a voyage that would carry her around the world as one of the 16 battleships of the “Great White Fleet.” President Roosevelt dispatched the fleet on a global circumnavigation to serve as a deterrent to possible war in the Pacific; to raise U.S. prestige as a global naval power; and, most importantly, to impress upon Congress the need for a strong navy and a thriving merchant fleet to keep pace with the United States’ expanding international interests and far flung possessions. In addition, the President wanted to discover what condition the fleet would be in after such a transit, noting before the fleet sailed: “I want all failures, blunders and shortcomings to be made apparent in time of peace and not in time of war.” Rear Adm. Evans stated earlier that his ships put to sea “ready at the drop of a hat for a feast, a frolic or a fight.”

President Roosevelt reviewed the fleet on 16 December 1907, as Kentucky and Alabama, Connecticut (Battleship No. 18), Georgia (Battleship No. 15), Illinois, Kansas (Battleship No. 21), Kearsarge, Louisiana (Battleship No. 19), Maine, Minnesota (Battleship No. 22), Missouri, New Jersey (Battleship No. 16), Ohio, Rhode Island (Battleship No. 17), Vermont (Battleship No. 20), and Virginia (Battleship No. 13) steamed past Mayflower off Hampton Roads. Hopkins (Destroyer No. 6), Hull (Destroyer No. 7), Lawrence (Destroyer No. 8), Stewart (Destroyer No. 13), Truxtun (Destroyer No. 14), and Whipple (Destroyer No. 15) screened the battleships during the first leg of their journey to the west coast. The train vessels included gunboat Yankton -- a converted yacht -- repair ship Panther, supply vessel Culgoa, and refrigerator ship Glacier.

Maine carried additional bags of coal on her deck to augment her bunkers in order to maintain her station in the voyage, but nonetheless experienced problems burning coal excessively. The ships charted southerly courses and visited Port of Spain (23–29 December 1907), crossed the equator on 6 January 1908, and anchored at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where a brawl between sailors from Louisiana and longshoremen marred the visit (12–22 January). Maine battled heavy wind and navigated through dense fog while passing through the Strait of Magellan, and visited Possession Bay (30 January–1 February) and Punta Arenas, Chile (1–7 February), and Callao, Peru (20–29 February). The Great White Fleet then carried out gunnery practice at Magdalena Bay, Baja California, Mexico (13 March–11 April).

Maine steamed with the fleet along the west coast and visited Californian ports: San Diego (14–18 April 1908); San Pedro (18–19 April); Santa Monica (19–25 April); Santa Barbara (25–30 April); Monterey (1–4 May); Santa Cruz (4–5 May); and San Francisco (6–18 May). Secretary of the Navy Victor H. Metcalf embarked in Yorktown (Gunboat No. 1) and reviewed the fleet while the ships put into San Francisco, and Rear Adm. Charles M. Thomas relieved Evans — whom Rear Adm. Charles S. Sperry subsequently relieved.

The voyage to the Pacific illustrated Alabama and Maine’s tendency to consume large quantities of coal. Rear Adm. Evans informed Secretary of the Navy Metcalf that Maine lacked “economical speed” and noted caustically that she burned nearly 30 tons of coal per day even when in port. Maine completed voyage repairs at Mare Island Navy Yard (10–23 May 1908), next (23–25 May) in dry dock at Hunters Point, and then further work pierside at San Francisco. The two battleships’ high coal consumption compelled planners to alter their timetable, so Nebraska (Battleship No. 14) relieved Alabama and Wisconsin (Battleship No. 9) relieved Maine.

Alabama and Maine consequently sailed from San Francisco on 8 June 1908 to complete their own, more direct, circumnavigation of the globe. The pair visited Honolulu in the Hawaiian Islands (16–22 July), and (6–14 July) just missed celebrating Independence Day while at Guam in the Ladrone Islands [Marianas]. They continued plotting westerly courses and visited Manila and Cavite Island in the Philippines (20–23 July and 23 July–1 August, respectively). The two battleships continued their voyage across the Pacific and toward the Indian Ocean, stopping first at Singapore (7–10 August), and then passing through the Strait of Malacca and heading westward, calling at Colombo, Ceylon [Sri Lanka] (16–20 August). Alabama and Maine visited Aden, strategically situated at the tip of the Arabian Peninsula (30–31 August), and turned northward into the Red Sea and made for the Suez Canal. The pair of warships passed through the international artery of commerce (6–11 September), and crossed the eastern Mediterranean and visited Naples, Italy (16–26 September). Alabama and Maine steamed westerly courses across the western Mediterranean and called at Gibraltar (30 September–4 October). The ships set out across the Atlantic from Gibraltar, stopped at San Miguel in the Azores (8–10 October), and returned to the United States at Portsmouth Navy Yard, N.H., on 19 October.

Maine accomplished voyage repairs at the yard, where she was also fitted out as a flagship (19 October–2 December 1908). Rear Adm. Conway H. Arnold, Commander, 3rd Squadron, Atlantic Fleet, broke his flag in Maine as she resumed operations along the Atlantic coast and into the warmer Caribbean waters during the next several months. The ship visited Fort Monroe (14–21 December), and turned her prow southward and celebrated the New Year (27 December 1908–17 January1909) at La Guaira, Venezuela. The warship visited Willemstad, Curacao (17–18 January), loaded stores at Guantánamo Bay (20–22 January), and rendezvoused with Mississippi (Battleship No. 23) at Key West, Fla. (24–25 January).

Sailing on 25 January 1909, the two battleships arrived at Habana [Havana] the same day, and represented the United States at the inauguration of José M. Gómez as President of Cuba, an event that had showed, as President Roosevelt declared upon Gomez’s election the previous November, “in impressive fashion the seriousness with which the Cuban people have now prepared themselves once more to assume the duties of a free and independent Republic.” Following the inauguration the two battleships parted ways, and while Mississippi made for Guantánamo Bay, Maine conveyed former U.S. Provisional Governor of Cuba Charles E. Magoon, whose tenure ended when Gómez became the Cuban chief executive, from Havana to Knights Key, Fla. (28–29 January).

Rear Adm. Arnold assembled the Atlantic Fleet’s Third Squadron at Guantánamo Bay, so Maine disembarked Magoon and swung around and rendezvoused with Idaho (Battleship No. 24), Maine, Mississippi, and New Hampshire (Battleship No. 25) at that anchorage. The four battlewagons turned northward from Cuban waters and greeted the returning Great White Fleet at 35º N, 55ºW, on 17 February. The ships then proceeded in company to Hampton Roads, where President Roosevelt reviewed the fleet on President George Washington’s Birthday — 22 February 1909.

Maine set out again for the Caribbean (1–8 March 1909) and fired at targets off Guantánamo Bay, and then (10–17 April) visited St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies [Virgin Islands]. The ship transferred and received men at Culebra on 17 April, called at Guantánamo Bay (20 April–7 May), and headed northward and completed repairs at Portsmouth Navy Yard (14 May–16 June). She then joined the Atlantic Fleet off Gloucester, Mass.

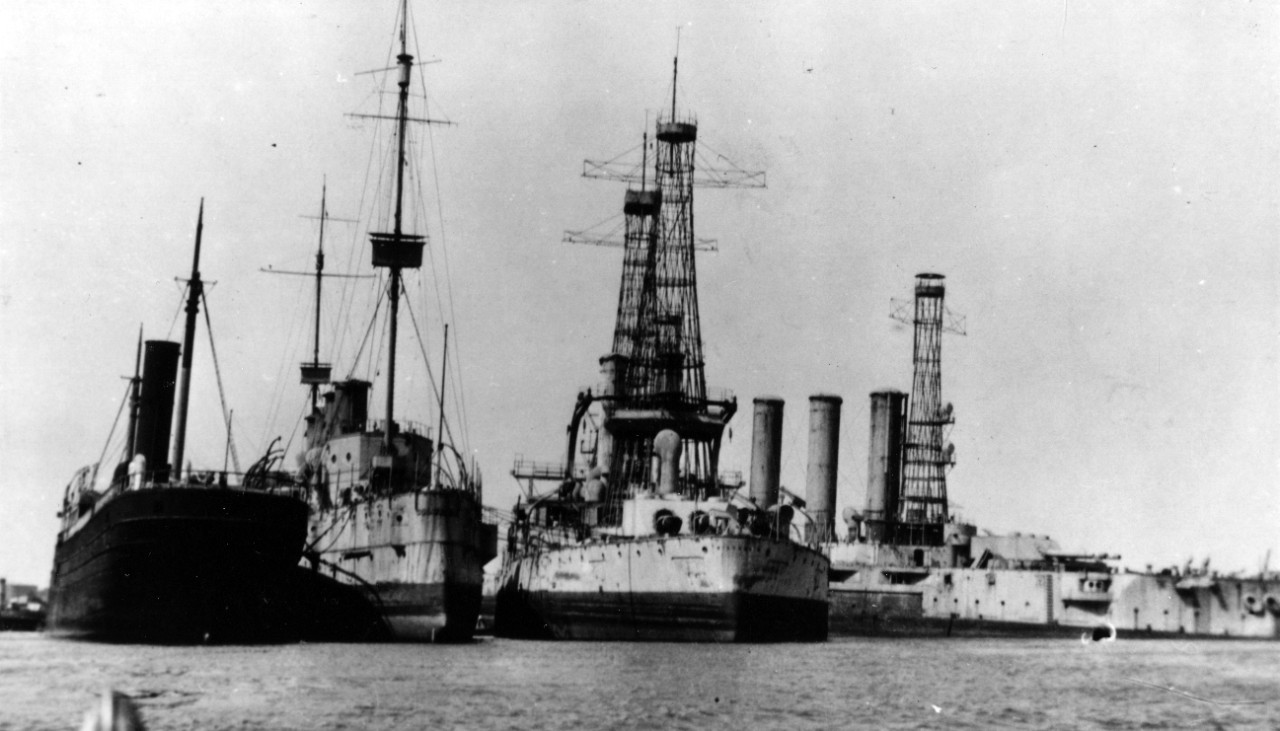

The ship was decommissioned at Portsmouth on 31 August 1909, where she was partially modernized. Maine was fitted with a pair of distinguishing cage masts, which supported multiple searchlights. Yard workers removed her forward and after bridges, as well as the light guns, and fitted forward and after keels to improve stability and sea keeping. In addition, they replaced the ship’s original Niclausse boilers with a new Babcock & Wilcox plant. The Bureau of Steam Engineering reviewed a proposal to reduce her stacks from three to two, but the Bureau of Construction and Repair and the Board of Construction vetoed the plan. The battleship emerged from the yard painted grey in lieu of her previous white-and-buff scheme, and in combination with the other work presented a dramatically altered silhouette.

Recommissioned briefly (15 June–6 December 1911), Maine operated along the east coast, training in particular on the Southern Drill Grounds. She was placed in first reserve at Philadelphia. The two M1895 Colt-Browning machine guns were removed in 1913. Placed in full commission for a cruise with midshipmen to European waters (4 July–18 September 1914), the ship lay with the Atlantic Reserve Fleet.

As the United States prepared to enter World War I, Maine was placed in commission in the Atlantic Reserve Fleet on 2 April 1917, and three days later in full commission. During the war she trained engineers, armed guard crews, and midshipmen, primarily while serving in the Battleship Force Home Guard at Philadelphia, steaming along the east coast from New York to Yorktown, Va. By May, Maine still mounted her four 12-inch guns but only ten 6-inch and six 3-inch guns, along with her two torpedo tubes. Workmen removed one of the 8-inch guns in August 1918, and a second such weapon in November, so that she carried her four 12-inch guns but just eight 6-inch and six 3-inch guns when the war ended. The guns were installed on board other vessels.

Maine, in full dress, held quarters to render honors as she joined 114 other ships in New York harbor while Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels reviewed them from Mayflower’s deck, and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt reviewed them from the armed yacht Aztec (S. P. 590), the day after Christmas of 1918. After the Armistice -- in 1919 -- Maine and Missouri each received a pair of 3-inch antiaircraft guns. Maine operated with ships of the Atlantic Fleet, though on 4 September 1919, was ordered to serve in reduced commission.

Maine was decommissioned at Philadelphia Navy Yard on 15 May 1920. Classified as BB‑10 on 17 July 1920, she was stricken and placed on the sale list on 1 July 1921; and on 22 August of that year appraised at a value of $120,000. The Navy sold her for $44,556, however, to J.G. Hitner & W.F. Cutler of 4501 Richmond Street, Philadelphia, on 26 January 1922. The service delivered the battleship to the company on 19 April 1922; which, on 17 December 1923, reported that it had rendered her incapable of further warlike service; and subsequently broke up Maine and scrapped her in accordance with the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty limiting naval armaments.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Capt. Eugene H.C. Leutze | 29 December 1902 |

| Capt. Charles T. Hutchins | 14 November 1904 |

| Capt. Nathan E. Miles | 15 July 1905 |

| Capt. Giles B. Harbor | 10 July 1907 |

| Capt. William B. Caperton | 31 July 1908 |

| Cmdr. Joseph W. Oman | 15 May 1911 |

| Cmdr. Robert K. Crank | 14 January 1913 |

| Cmdr. Milton E. Reed | 1914 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Pope Washington | 1916 |

| Cmdr. Montgomery M. Taylor | 27 June 1916 |

| Cmdr. Joseph M. Reeves | 1 December 1917 |

| Capt. Roscoe C. Moody | 5 September 1918 |

Mark L. Evans

22 February 2018