Barker (Destroyer No. 213)

1919–1945

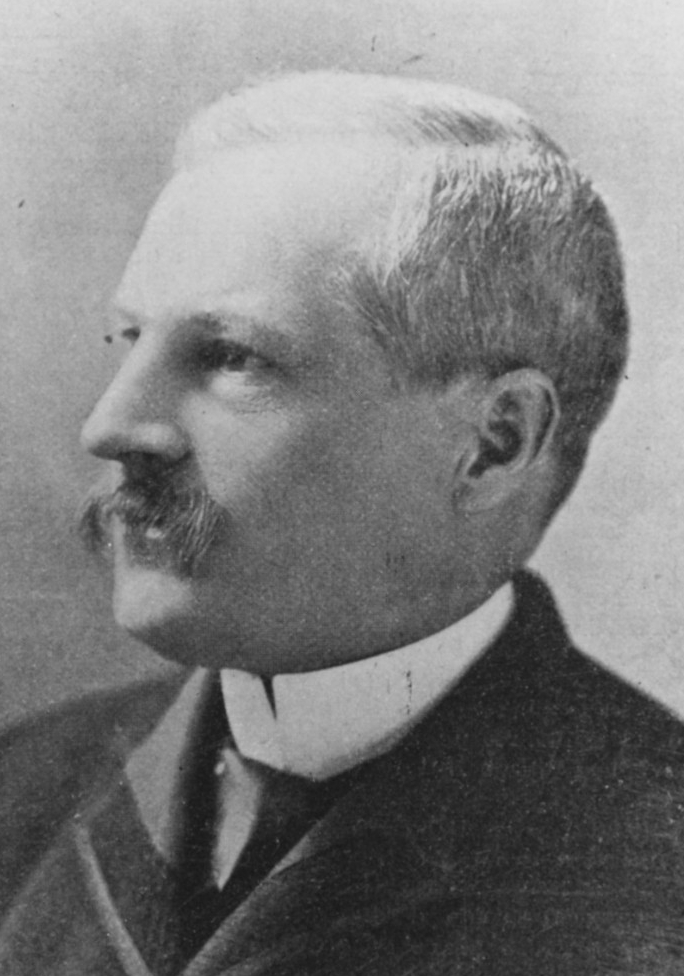

The first U.S. Navy ship named for Albert Smith Barker, born to Josiah B. Barker in Hanson, Mass., on 31 March 1845. He was appointed a midshipman at the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md., on 25 October 1859. One summer he served briefly in sloop-of-war Plymouth, which operated as a school ship for that class. While on board Plymouth, the midshipmen slept in hammocks swung on the gun deck so close that they touched, and generally shared the cramped space with enlisted men, though they maintained their own private lockers. Barker afterward recalled humorously that his fellows made his first night “uncomfortable” when they lashed him up in his hammock and let him down on the run, either feet first or head first, “as pleased the hazer”.

Barker somberly observed, however, that he and many of the other midshipmen “distinctly” felt the “unrest and talk of disunion” that led up to the outbreak of the American Civil War, but that he “welcomed the approach of the practice cruise and gladly saw the bulkheads of the study rooms on the Plymouth taken down and the vessel fitted for sea”. Barker sailed in Plymouth to Gosport Navy Yard at Norfolk, Va., in June 1860. While Plymouth underwent painting and repairs he served on board ship-of-the-line Pennsylvania, which operated as a receiving ship. When Plymouth completed her work, Barker sailed on board the sloop-of-war to: Fayal in the Azore Islands; the Madeiras; Cadiz, Spain; the Canary Islands; and then back to Chesapeake Bay. The still novice seaman afterward unabashedly recalled that he suffered from the bane of mariners and endured seasickness for a few days that summer. When he recovered he set to the food with relish, despite the limited fare of ‘hard tack’, ‘soft tack’, salt horse, ham, potatoes, dried apples, butter, and cheese. Barker described the soft tack as “hot biscuit” but added that what appeared to be an appetizing staple proved “heavy as lead”. The men developed the even more disturbing custom of rendering the hard tack, which he described as “hard square crackers”, fit for consumption by banging the crackers on the table cloth to knock the worms out before eating the repellent regimen. He good naturedly summarized their meager meals at sea by adding that in the event that the ship had fired off the last of her round shot, they could have loaded the guns with the cheese wheels. He hoped their meals would improve upon their return but lamented that their daily fare then consisted of a spoonful of potato soap, a potato, a cup of coffee, and all the hard tack they could stomach — while in agonizing view of the seaside resorts in Hampton Roads.

As the war clouds loomed on the horizon, the midshipmen’s drills took on a special urgency and earnestness. Frigate Constitution relieved Plymouth as the school ship, and they transferred the fieldpieces and ammunition to the famed man-of-war. They spiked the old Mexican guns that adorned the Naval Academy’s grounds, and began to arm themselves and formed companies to defend the institution. A company stood under arms night and day, because they sometimes sighted Confederate cavalry drilling across the Severn River and expected an attack hourly. Steamer Maryland, with two companies of the 8th Massachusetts Volunteer Militia embarked while en route to defend the nation’s capital, anchored alongside Constitution on the night of 20 April 1862. Two days later, the 7th New York Militia arrived to temporally reinforce the Naval Academy’s garrison. The Massachusetts soldiers disembarked three days later, and Barker provided a glimpse of his leadership capabilities when he empathetically noted that the New Englanders had lain on decks covered with coal dust but that “their spirit was excellent”. The Massachusetts militiamen seized the railroad station and rapidly repaired the locomotives that the Confederates had disabled. Some soldiers from Rhode Island also reinforced these commands. The midshipmen then embarked on board Constitution, Commodore George Rodgers in command, and during an emotional ceremony in which many broke down and openly wept, set out for New England waters. The frigate touched at New York, where some of the men heard Christian evangelist and abolitionist Henry W. Beecher preach in Plymouth Church, and then resumed her voyage to Newport, R.I.

Barker detached from the Naval Academy, and on 13 May 1861 reported on board Mississippi, Capt. Thomas O. Selfridge in command, at Charlestown Navy Yard, Mass. The side-wheel steamer was commissioned on 22 December 1841, had served during the Mexican American War, and Matthew C. Perry had broken his flag in her during the commodore’s expedition to Japan. Mississippi completed repairs in June and then turned her prow southward to join the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, Rear Adm. David G. Farragut in command. While setting out once more to sea from Key West, Fla., the ship ran aground on the Triangles, a shoal not marked by buoys. A number of the Union officers suspected the pilot of Southern sympathies because he had run another ship aground a short time before, but Mississippi took on coal and heavy stores, refloated, and two days later rendezvoused with steam frigate Niagara, bark Release, and side wheel steamer Water Witch off Fort Pickens at the entrance to Pensacola, Fla.

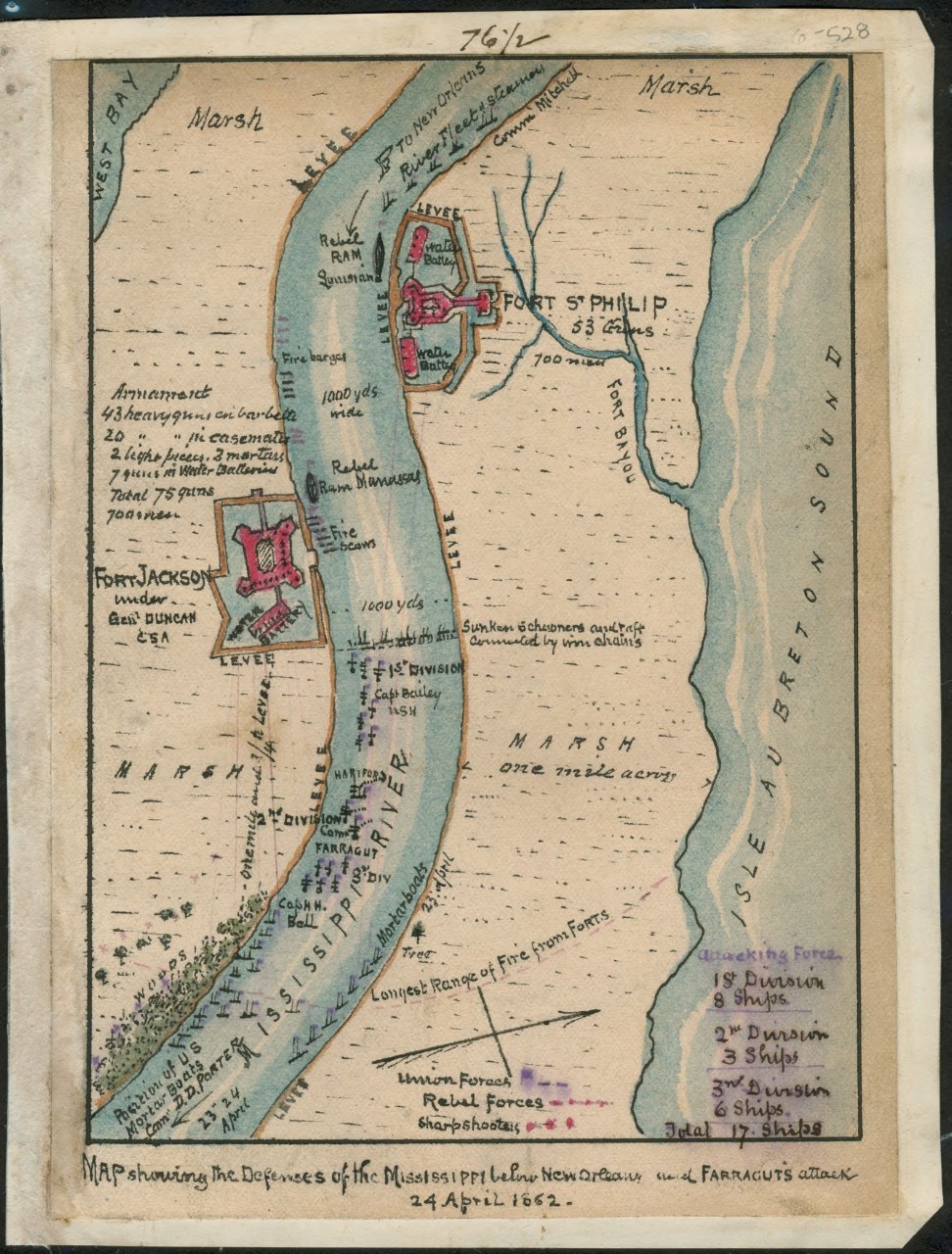

The young officer patrolled for blockade runners in the Gulf of Mexico, and then took part in the assault on the vital Confederate port of New Orleans, La. Brig. Gen. Johnson K. Duncan, CSA, commanded the Southern troops that manned two bastions to defend the approaches to the bustling city, Fort Jackson on the Mississippi River’s western shore, and Fort St. Philip on the eastern bank. Their ships served in three separate forces, however, compounding command and control issues. Armored ram Manassas, Lt. A.F. Warley, CSN, in command, and uncompleted ironclads Louisiana and Mississippi comprised a trio of potentially powerful men-of-war, supplemented by a pair of converted merchantmen, Jackson and McRae. The River Defense Fleet, Flag Officer John K. Mitchell, CSN, in command, included cottonclad rams Defiance, General Breckinridge, General Lovell, Resolute, Stonewall Jackson, and Warrior. Further vessels included transport Diana, steam tenders Landis and W. Burton, tender Phoenix, and steamers Belle Algerine and Mosher. Finally, the Louisiana Provisional Navy deployed steamers General Quitman and Governor Moore. In addition, the Confederates linked hulks together by a huge chain and stretched them across the river to block Union ships from advancing up the Mississippi, and their efforts collectively posed a formidable challenge to any attacking force. Farragut led a total of 17 ships mounting 154 guns, supported by a flotilla of 20 mortar boats, Cmdr. David D. Porter in command.

After several attempts, Mississippi, in company with screw steamer Pensacola, Capt. Henry W. Morris in command, successfully passed over the bar at Southwest Pass, one of the mighty river’s channels, on 7 April 1862. On 18 April, Porter’s mortar boats began bombarding Fort Jackson. Capt. Henry H. Bell led a pair of gunboats, Itasca and Pinola, and broke through the boom two days later. Duncan lamented the lack of coordination between the disparate Confederate commands, and complained that the River Defense Fleet failed to send fire rafts “to light up the river or distract the attention of the enemy at night”, adding that they also neglected to deploy ships to warn of a Union incursion. The Confederate garrison of Fort Jackson resisted stoutly, however, and Farragut resolved to boldly advance his squadron up river past the forts, counting on darkness and the smoke from gunfire to help obscure his ships. The flag officer deployed his squadron in three divisions, the First (eight ships), Center (three), and Third (six), led by Capt. Theodorus Bailey, Farragut, and Bell, respectively. Mississippi, Capt. Melancthon Smith in command, was to proceed as the third ship of the First Division.

Farragut broke his flag in screw sloop-of-war Hartford as he led the Union ships up the Mississippi during the mid watch on 24 April 1862, at 0200 signaling the three divisions to begin their perilous voyage. The ships of the three divisions concentrated in two columns and set out about an hour later, but as they approached the breach in the boom, enemy lookouts sighted their silhouettes and sounded the alarm. The Confederates opened a withering fire, and the Union ships blasted their way past with thunderous broadsides, though both sides failed to score many hits in the confusion of the night battle. Farragut’s daring move paid off as most of the Northern ships steamed through the torn boom, although a round incapacitated Itasca’s boilers and she drifted out of the fighting, while a pair of gunboats, Pinola and Winona, came about as the sun rose.

Some of the Confederate ships then attacked the Union squadron, but they did so piecemeal and a series of ship to ship duels ensued. Manassas churned toward the invaders and attempted to ram Pensacola but the steamer deftly turned and dodged her blow. The ram continued and in turn fired on and rammed Mississippi and sloop-of-war Brooklyn. Both Union ships survived and shot at the enemy ram, which also took fire from her own shore batteries in the fiery maelstrom. Mississippi then wrecked Manassas with two mighty broadsides, and Warley ordered his men to ground Manassas and set her alight to prevent the Northerners from capturing the ram. The Confederate sailors ignited their fires and abandoned ship, but Manassas defiantly floated free and drifted downstream past the Union mortar boats. Porter hoped to capture and examine the prize, but she eluded his grasp when she exploded and sank. Seaman Christopher Brennan of Mississippi’s ships company afterward received the Medal of Honor for his “skill and courage throughout the entire engagements”. Governor Moore and Stonewall Jackson rammed gunboat Varuna, Cmdr. Charles S. Boggs in command, which sank in the shallows, the only Northern ship lost in the battle. The Union ships sank General Breckinridge, General Lovell, Stonewall Jackson, Warrior, Phoenix, Belle Algerine, Mosher, and General Quitman. The Confederates scuttled Louisiana, Mississippi, Resolute, Defiance, and Governor Moore to prevent their capture. Landis and W. Burton struck their colors, and McRae was damaged but survived, only to sink at her moorings.

The high water in the river enabled the Union ships’ guns to range over the levee, and Farragut demanded the surrender of the doomed city the next day. On 26 April he issued a general order: “Eleven o’clock this morning is the hour appointed for all the officers and crews of the fleet to return thanks to Almighty God for His great goodness and mercy in permitting us to pass through the events of the last two days with so little loss of life and blood. At that hour the church pennant will be hoisted on every vessel of the fleet, and their crews assembled will, in humiliation and prayer, make their acknowledgments therefor to the great dispenser of all human events.”

New Orleans surrendered on 28 April, and on 1 May, Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler’s soldiers began landing to occupy the city. The capture of New Orleans deprived the Confederates of their largest city and a valuable port, and helped persuade the British and French to minimize their support of the Southerners. The victory also opened the lower Mississippi to further operations, and Farragut spent some days repairing his ships and then deployed them northward in additional attacks that netted Baton Rouge and Natchez. Mississippi’s heavy draft made her largely unsuitable for river operations, however, and she mostly remained off New Orleans into the next year.

The fighting for control of the Mississippi basin raged throughout the rest of the year and into 1863. During the winter the Union Army of the Tennessee, Maj. Gen. of Volunteers Ulysses S. Grant in command, invested Vicksburg, Miss. -- the garrison led by Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton, CSA -- the principal remaining Confederate bastion on that strategic river. The Northern operations included a plan to establish a blockade at the mouth of the Red River, from which enemy ships entered the Mississippi. Union ships had to pass Port Hudson, La., however, in order to reach the area. The Confederates there, led by Maj. Gen. Franklin Gardner, CSA, emplaced strong artillery batteries manned by a combination of soldiers and sailors along the river, making such an attempt a daunting prospect. In spite of Farragut’s success the previous year, centuries of naval experience indicated that emplacing guns ashore, which improved their steadiness (and thus accuracy), and protecting them by earthworks or stouter fortifications, often rendered the contest between ships and shore an unequal one.

Farragut nonetheless needed to pass Port Hudson, and he inspected the squadron of seven ships he selected for the arduous task on 13 March 1863. The admiral also conferred with Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks and they arranged for the Army to support the Navy by engaging the enemy batteries from ashore. Banks’ mortars began bombarding the Confederates on the night of 14 March, and at about 2200 the squadron got underway and began moving upriver. The Union vessels set out lashed in pairs, the heavier ships steaming to inboard to screen the lighter vessels from the enemy guns, which lay to starboard (along the east bank). Hartford and screw steamer Albatross led the column, followed in order by steam sloop Richmond and side wheel steamer Genesee, screw sloop-of-war Monongahela and ironclad gunboat Kineo, and then Mississippi singly, which brought up the rear. Farragut later explained his selection of Albatross as Hartford's partner: “Albatross being the most vulnerable of the gunboats, and her speed being about equal to that of this ship, was assigned to her…”

Hartford and Albatross weathered the hail of shot. “She returned our fire boldly,” Gardner summarized the screw steamer’s foray. While the flagship and her consort passed the lower batteries, the current nearly swung the pair around and grounded them; “but,” Farragut reported, “backing the Albatross, and going ahead strong on this ship, we at length headed her up the river.” Though able to bring only two guns to bear on the upper batteries, Farragut successfully passed those works.

The Confederate gunners fired furiously, however, and the following ships suffered frightfully. The enemy fire mortally wounded Cmdr. Andrew B. Cummings, Richmond’s executive officer, and a 42-pounder shell ruptured her steam lines, filling the engine room and berth deck with live steam. Genesee labored unavailingly against the current and could not tow Richmond through the fray. A 6-inch shot pierced her hull and detonated a 10-inch shell which, in turn, wreaked havoc below; and the murderous fire shredded her rigging. Both ships consequently dropped out of the action and drifted downriver.

Next in line, a shot disabled Monongahela's rudder causing her and Kineo to run hard aground under Port Hudson’s lower batteries, where she remained for nearly half an hour, taking severe punishment. At least eight rounds passed entirely through the ship. The bridge was shot from underneath Capt. James P. McKinstry, wounding him and killing three others. Kineo helped Monongahela refloat; and she gamely attempted to resume her course upriver. “We were nearly by the principal battery,” Lt. Nathaniel W. Thomas, the executive officer, wrote, “when the crank pin of the forward engine was reported heated, and the engine stopped…” The ship became unmanageable and drifted downstream, where she anchored out of range of the Confederate guns. Monongahela lost six men killed and 21 wounded, including the captain.

Meanwhile, on board Mississippi, Capt. Smith saw Richmond coming downstream but, the heavy smoke of the battle prevented him from sighting Monongahela. Thinking that she had steamed ahead to close the gap caused by Richmond's leaving the formation, he ordered his ship “go ahead fast”. In attempting to do so, Mississippi ran aground and, despite every effort by her crewmen, who included Barker and George Dewey, the future victor of the Battle of Manila Bay, could not be brought off. Smith decided to scuttle Mississippi to prevent the Confederates from seizing the side-wheel steamer. The ships company scrambled to destroy machinery and spike the guns, and then set her afire in four places. Barker joined the survivors as they abandoned ship, and at 0300 they watched the burning ship float slowly down river. Two and one-half hours later, the flames reached the magazines and Mississippi blew up, effectively ending the fierce battle. Three men of the ships company, Boatswain’s Mate Peter Howard, SN Andrew Brinn, and Sgt. Pinkerton R. Vaughn, USMC, subsequently received the Medal of Honor for their heroism and valor. Mississippi lost 64 killed, and the ships in company saved 223 of her crew, including Barker. Farragut continued upstream to Warrenton, Miss., just below Vicksburg, contacted Porter on 20 March, and began to blockade the Red River. Grant subsequently captured Vicksburg and the Union forces then took Port Hudson, the victories effectively cutting the South in two.

Following that terrifying trial, Barker was transferred to screw sloop-of-war Monogahela, and took part in blockading patrols of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron. He then (9 August 1863) shifted to steam frigate Niagara, while she was temporarily decommissioned and completed repairs at Boston Navy Yard, Mass. Niagara was recommissioned on 14 October 1863, and in February 1864 Barker shifted to screw sloop-of-war Lancaster, flagship of the Pacific Squadron. On 11 November 1864, a secret expedition of boats from Lancaster captured a party of Confederate officers in passenger steamer Salvador, outside the Bay of Panama. They had planned to seize Salvador for the Confederate Government and convert her into a raider to capture Union gold shipments from California. In the spring of 1866, Lancaster received extensive repairs at Mare Island Navy Yard and on 27 June sailed from San Francisco for the east coast, via Panama Bay, Callao, Valparaiso, Barbados, and Nassau. She arrived at Norfolk Navy Yard on 8 March 1867, and was decommissioned on 19 March. Barker then cruised in the various stations and served in prominent positions ashore.

He relieved Cmdr. Edwin M. Shepard in command of screw sloop Enterprise at Norfolk Navy Yard on 8 December 1882. On New Year’s Day 1883, Barker took Enterprise to sea for a hydrographic survey that carried her across the world during a global circumnavigation. The ship visited Porto Grande in the Cape Verde Islands (2–8 February), and from there she sailed down the West African coast and around the Cape of Good Hope, stopping: at Capetown (31 March–11 May) and the autonomous municipality of Port Elizabeth (14–26 May) in Cape Colony; and Durban, Natal (28 May–1 June). Enterprise then put in to: St. Augustine Bay (7–30 June) and Tamatave (Toamasina — 5–6 July) on Madagascar; and Johanna Island (Anjouan) in the Comoros (10–13 July). From there she visited Zanzibar (16–24 July), where Barker compiled information for Trade of Zanzibar, a report he later submitted concerning the island’s imports and exports during the years 1882–1883. The Americans, British, French, and Germans dominated the trade with the sultanate, and the British maintained their two decker London on that station as a store ship. Enterprise wrapped-up her sojourn in East African waters by visiting Mahé in the Seychelles Islands (16–24 July).

Barker then charted a course across the Indian Ocean and into the Asiatic Station and visited: Batavia (Jakarta), Java (4–19 September); Singapore (30 September–1 October); Hong Kong (9–12 October); and along the Chinese coast to the Yangtze and Whangpoo (Huangpu) Rivers, where the ship put in to Shanghai (17 October–17 November). Barker took the sloop across the Western Pacific and visited: Nagasaki, Japan (20–24 November); lay to at several islands; visited Rose Island off Chemulpo (Incheon), Korea (4–12 December); Nagasaki again (14–20 December); and then back to Rose Island (23 December 1883–4 February 1884). Enterprise turned her prow southward toward Chinese waters and visited Chefoo (Yantai), Shanghai, and Amoy (Xiamen), setting out from the latter on 16 May for visits to: Foochow (Fuzhou — 17–24 May); Ningpo (Ningbo — 26–28 May); Shanghai; Nagasaki; Kobe and Yokohama, Japan; Shanghai; and Foochow on 22 August 1884.

Enterprise returned to Foochow at a turbulent time because French and Chinese troops had just clashed and stood poised to fight the Sino-French War. Barker therefore landed two parties, one led by Lt. Hugo Osterhaus and 51 bluejackets, and the other commanded by 2nd Lt. T. Glover Fillette, USMC, and 19 marines, to protect Americans ashore. The following day, Enterprise lay at the Pagoda Anchorage and her crew observed the Battle of Foochow as the French Far East Squadron, Adm. Anatole-Amédée-Prosper Courbet in command, defeated the Chinese Fukien (Fujian) Fleet, Imperial Commissioner Zhang Peilun in command. The area seethed for some time and the landing parties only returned to the ship on 3 September. On 7 September she stood down the channel for months of visits to: Shanghai; Chefoo; Nagasaki; Shanghai; Amoy; Foochow; and Hong Kong, from which she set out on 28 July 1885. Enterprise visited Surabaya, Java (10–16 August); Albany (6–8 September) and Melbourne (16 September–15 October), Australia; Wellington, New Zealand (26 October–6 November); and then steamed across the South Pacific to Punta Arenas (Sandy Point), Chile, and through the Strait of Magellan on 19 December 1885. The ship wended her way up South America’s east coast and the Caribbean and visited: Montevideo, Uruguay (1–9 January 1886); Bridgetown, Barbados (26 February–2 March); St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands on 5 March; and reached New York on 17 March. Enterprise was decommissioned there and Barker relieved of her command on 21 March, after sailing around the world for three years, and the hydrographic findings on the voyage adding materially to the knowledge of the oceans, their currents, and their bottoms.

Following additional assignments, Barker then (28 July 1890–24 August 1894) commanded Philadelphia (Cruiser No. 4). The Americans helped orchestrate a coup d’état that overthrew Hawaiian Queen Lili’uokalani on 17 January 1893. The resulting crisis heightened tensions across the Pacific, and while Barker oversaw maintenance work on Philadelphia at New York Navy Yard he received orders to deploy her to that ocean “with dispatch”. On the night of 20 June he took Philadelphia, loaded with 40 tons of coal on the deck and a great store of coal in the firerooms, from Tompkinsville, N.Y., piloting the ship himself through the dredged channel and out to sea. Navy planners debated the steaming radius of the new types of cruisers, and Barker proudly reported that Philadelphia steamed without stopping her engines 4,834 nautical miles and reached Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on the morning of 11 July. The ship counted more than 200 tons of coal still remaining at that point, so that she could have continued the voyage without immediately having to carry out the laborious and gritty task of coaling.

The Americans arrived at an unsettling time, however, because rival Brazilian factions fought in some parts of the country. Barker observed that the Brazilian warships normally lay to without power because their government feared that the ships’ officers might join the rebels and fire on the city. The news of an incident of more immediate concern to mariners across the globe also caused consternation among the ships company. British battleship Victoria collided with Camperdown off Tripoli, Lebanon, on 22 June. Victoria sank quickly, taking Vice Adm. Sir George Tryon, RN, Commander Mediterranean Fleet, who broke his flag in the ship, and 357 other men to the bottom. Camperdown survived the collision, though required extensive repairs. Barker and the officers of the wardroom discussed the accident and debated procedures of the road and maneuvering in formation.

Philadelphia charted her further course into the cold southern waters on 17 July 1893, anchoring three times in the Strait of Magellan to avoid running the unlighted strait at nighttime. The ship did not stop at Punta Arenas, but plowed through heavy seas as she followed the west coast of South America and reached Callao, Peru, on 7 August. Philadelphia accomplished some voyage repairs and yard work on her plant while there, and then set out for Hawaiian waters, arriving at Honolulu to reinforce protected cruiser Boston and screw steamer Adams on 13 September. Thousands of Hawaiians lined the wharves as the ship entered the harbor, because rumors had spread that Barker was to restore Queen Lili’uokalani to power!

He made the usual round of receptions and events, and at one point attended a ball at the Executive House -- the newly renamed ‘Iolani (Royal) Palace -- amid fears that the Royalists might attempt to dynamite the building. Barker consequently recommended to Commodore Joseph S. Skerrett, Commander Asiatic Station, that they maintain men of the two warships as two landing forces ready to intervene in the event of an attack, and arranged that they could warn the ships during a disturbance by firing rockets and Very signals. Philadelphia subsequently relieved Boston, which had spent nearly 13 months in Hawaiian waters and then departed, but the situation required the sailors and marines to be ready at a moment’s notice to protect Americans ashore. Barker nonetheless portrayed the traditional Hawaiian hospitality as very enticing for his men, noting that they entertained them “constantly in a princely manner”. He feared the effects of this hospitality on his men and acted as a stern disciplinarian, establishing a rule that all of the ships company, from himself to the newest recruits, were to serve on board Mondays through Saturdays until after forenoon drills, and on Sundays until after inspections.

Tensions continued between the native Hawaiians and the settlers, primarily between the Royalists and the Provisional Government of Hawaii, and pushed Barker’s diplomatic skills and command responsibilities. People spoke of an outbreak of fighting, and additional ships in the harbor, including British corvette Champion, Capt. Rookes, RN, in command, and Japanese protected cruiser Naniwa, Capt. Tōgō Heihachirō, offered their services to Barker to protect Britons and Japanese trapped in the islands. Rookes, in particular, told Barker that he could deploy 100 men for “patrol duty”, and a detachment to guard the British Legation. The Americans and Japanese, however, failed to adequately coordinate their operations and Barker faced the crisis unaware of their intended positions ashore.

When revenue cutter Thomas Corwin, carrying dispatches for United States Minister to Hawaii Albert S. Willis, arrived on 14 December, she generated heated controversy because rumors circulated that her arrival portended that the U.S. intended to restore the queen. Barker acted diplomatically, however, and on 19 December instructed Philadelphia’s landing force “to remain neutral” and to “protect the lines and property of Americans citizens—and other foreigners who seek protection—who take no active part on the side of the Provisional Government or of the Queen”. The crisis during this time gave rise to the popular term “Black Week”, but the disparate parties largely avoided bloodshed and negotiated into the New Year, and the Americans overcame further Hawaiian resistance and proclaimed the Republic of Hawaii on 4 July 1894. Additional ships including British, French, and Japanese vessels all sailed in Hawaiian waters during the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, and kept Barker busy working with the various foreign powers.

Barker took a much needed break and embarked on board inter-island steamer Kinau at Honolulu and made landfall at Hilo on the island of Hawaii, where he ascended to the snow-covered volcanic summits of Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea (11–19 May). Just before Philadelphia set out from the islands, an entourage of about 120 international dignitaries, Christian missionaries, and Hawaiian officials held a luau for Barker and his officers beneath a tent. The hosts laid the sumptuous feast on cloth spread on the grass, and Barker and about 20 of the guests ate while seated at a table, and the rest of the people on the ground. Despite the hospitality, the captain complained about using his fingers instead of silverware, adding that “one of those feasts would do for a year”. The ship’s port engine failed at a critical moment as she sailed on 12 August and Barker took her through the channel without a pilot and then lay too while engineering crewmen cooled and adjusted the hot bearings, and the cruiser continued her journey, entering San Francisco Bay through a dense fog on 22 August. The following day Philadelphia moored at Mare Island Navy Yard, where she subsequently completed an overhaul in drydock. Capt. Charles S. Cotton relieved Barker on 24 August, and he accompanied Rear Adm. John G. Walker, who had been relieved by Rear Adm. John Irwin as Commander Pacific Station on 7 June 1893, as they left in a private railway car that one of Walker’s railroad friends placed at their disposal.

Barker married Ellen B. Maxwell in 1894. Born to John Simmons and Rebecca M. Blackmar at West Springfield, Pa., she worked as a writer and editor, and penned The Bishop’s Conversion, Three Old Maids in Hawaii, and The Way of Fire. She had wed Rev. Allen J. Maxwell in 1879, but in 1890 he died at Lucknow, India, then under British rule. Barker’s family also included his nephew, Albert C. Read, who subsequently gained fame as a lieutenant commander when he became the primary pilot of flying boat NC-4 (BuNo. A-2294), the first plane to fly across the Atlantic (8–21 May 1919).

As the Spanish-American War approached Barker served on the Board of Strategy, and then took command of Newark (Cruiser No. 1). Following an extensive overhaul, Newark was recommissioned on 23 May 1898, shortly after the U.S. declared war on the Spaniards. She sailed on 13 June for Key West, Fla., and the following day, the Army’s V Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. William R. Shafter, set out from Tampa, Fla., for Cuba. Rear Adm. William T. Sampson, Commander North Atlantic Squadron, and Shafter conferred about their divergent strategies on 20 June. Sampson hoped that the Army intended to capture the shore batteries around Santiago to enable the Navy to overwhelm the defenders, but Shafter preferred that the Navy support the advance on the city. Shafter landed his troops at Daiquirí (22–25 June) and then pushed toward Santiago, but disease savaged the men and they sustained alarming casualties during their advance toward El Caney and San Juan and Kettle Hills.

Newark meanwhile made for Cuban waters, where she joined the blockade of that island on 30 June. On that date Shafter also requested that Simpson, who broke his flag in New York (Armored Cruiser No. 2), take part in an attack against those heights the next day. The Navy was to deploy ships along the Army’s left flank and support Brig. Gen. Henry M. Duffield, while he directed an assault by the 33rd Michigan Regiment against Spanish positions near the Aguadores River in an effort to draw-off some of the defenders from El Caney and San Juan and Kettle Hills. Barker consequently steamed Newark to rendezvous with New York, converted yacht Gloucester, and armed vessel Suwanee, and they demonstrated against enemy troops deployed near the entrance of the harbor of Santiago de Cuba. The ships shelled the Spanish fort, rifle pits, and beach, but they fired ineffectively because of the lack of spotters. The Spaniards defiantly flew their colors throughout the bombardment and when Sampson signaled “cease firing”, Lt. Cmdr. Daniel Delehanty, Suwanee’s commanding officer, requested permission to attempt to knock down the flag. Sampson authorized Delehanty to fire no more than three rounds, and Suwannee resumed shooting a 4-inch gun from a range of 1,300 yards: the first shell rent the flag, the second struck near the base of the staff, inclining it about 20° from the vertical, and the final round shot away the flag and staff. The Americans’ failure to adjust their fire, however, enabled the Spaniards to otherwise escape the bombardment.

The following day Indiana (Battleship No. 1) and Oregon (Battleship No. 3) -- which had just accomplished an extraordinary voyage from the Pacific around South America -- bombarded the Spanish artillery emplacements at the entrance of the harbor, concentrating on the Punta Gorda battery. Sampson dispatched a report of this bombardment to Shafter, observing that he could not force an entrance to the harbor until they could clear the channel of mines. The admiral added that enemy shore fire precluded the likelihood of successful minesweeping, and the urgent necessity of the seizure of the forts at the entrance to the harbor by the V Corps. Shafter conferred with his staff and replied that he could not provide a definite answer concerning the seizure of the batteries at the harbor’s mouth, “to avoid future losses among my men” and urged that a naval assault force the entrance. Sampson countered by pointing out that the guns of the forts guarding the harbor fired to seaward and did not seriously threaten Shafter’s advance, but that the mines strewn across the harbor imperiled his ships. Sampson conceded that he would prepare such an operation if Shafter demanded it, but hoped that an attack by the Army on the shore batteries from the rear would leave the Navy at liberty to drag the channel for mines. Because of their impasse, Sampson agreed to meet Shafter at Siboney, east of Santiago, the following day on 3 July. Early that morning, the admiral sailed toward Siboney on board New York, escorted by torpedo boat Ericsson.

The American advance threatened to seize the heights overlooking the city, and artillery emplaced on those hills could sweep the harbor. Captain-General Ramón Blanco y Erenas therefore ordered Rear Adm. Pascual Cervera y Topete, who commanded the Flota de Ultramar (Caribbean Squadron), to attempt to escape, thus precipitating the Battle of Santiago de Cuba. Newark steamed as part of the blockade and missed the battle, but cruised off the Cuban coast throughout the summer. Capt. Caspar F. Goodrich relieved Barker as the commanding officer on 2 August, and Barker then took command of Oregon. Following the fighting Oregon completed an overhaul in New York and in October set a course for what the Navy announced as “special service” in the Pacific. Filipino insurgent leader Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy initially fought the Spaniards in those islands, but when U.S. soldiers, marines, and sailors began to occupy the Philippines he led an insurrection against the Americans. Barker brought Oregon into Manila on 18 March 1899, and he led the battleship as she patrolled against the insurrectos during the succeeding months. In addition, he temporarily relieved Commodore George Dewey in command of the Asiatic Squadron (20 May–20 June 1899) until Rear Adm. John C. Watson reached the region and relieved Dewey.

Barker served ashore first as Commandant of the Norfolk Navy Yard, Va. (October 1899–July 1900), and then as Commandant of the New York Navy Yard (and station) until Rear Adm. Frederick Rodgers relieved him (17 July 1900–1 April 1903). Barker received orders to proceed to Washington, D.C., and report to the President of the General Board on 25 April. Three days later he boarded armed yacht Mayflower and steamed down the Potomac River and out to the Southern Drill Grounds off the Virginia capes, where on 29 April he inspected ships of the fleet including: Alabama (Battleship No. 8), Illinois (Battleship No. 7), Iowa (Battleship No. 4), Kearsarge (Battleship No. 5), Massachusetts (Battleship No. 2), battleship Texas, Olympia (Cruiser No. 6), transport Prairie, several destroyers, a supply steamer, a collier, and some smaller craft. Barker relieved Rear Adm. Francis J. Higginson as Commander-in-Chief North Atlantic Fleet, and broke his flag in Kearsarge, on 30 April.

The admiral then attended the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration in New York, where he spoke briefly but eloquently. “The speech was a perfect one,” Dr. St. Clair McKelway, editor of the Brooklyn Eagle, observed, adding, “and I know what I am talking about.” Upon returning to the New York Navy Yard, Barker discovered orders to shift his flag to Mayflower while Kearsarge sailed to Kiel, Germany, and to England. He then transferred his flag to Illinois, and led Alabama, Massachusetts, Brooklyn (Cruiser No. 3), Mayflower, and colliers Caesar, Lebanon, and Sterling from Tompkinsville across the Atlantic to the Azores (25 June–23 July 1903). The admiral “distributed” the vessels about the islands because the ships companies comprised too many men to venture ashore on liberty in any one of the small ports.

While Illinois lay to at Horta at Fayal in those islands, a representative of the Commercial Pacific Cable Co., named Hughes told him that a global cable opened on (U.S.) Independence Day and President Theodore Roosevelt set a message from Oyster Bay, N.Y., to Clarence H. Mackay of that company in approximately 12 minutes. The message traveled westward via multiple stations including: San Francisco, Calif.; Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands; Midway Island; Guam; Manila, Philippines; Straits Settlements, Malaya; Horta; Nova Scotia, Canada; and so to Oyster Bay. The president stood alongside Mackay as he sent him the missive: “Congratulations and success to the Pacific cable, which the genius of your lamented father and your own enterprise made possible. Theodore Roosevelt.” Mackay replied to the chief executive, his response taking about nine and a half minutes to travel eastward. Barker marveled at the speed of transmitting these messages. The ships set out from Horta on 14 July, rendezvoused with Alabama as she stood out of Punta Delgada, and charted westerly courses. Brooklyn detached and made for European waters, and on 20 July Mayflower parted company bound for New York. The admiral took the rest of the ships to Frenchman’s Bay, Maine, noting that the weather during their return voyage turned “disagreeable”.

Barker led the ships of the fleet in a series of “problems” (maneuvers) in New England waters and then many of them anchored in Smithtown Bay, L.I., on 14 and 15 August, and then (15–17 August) took part in a Naval Review at Oyster Bay. The foreign naval attachés embarked on board Kearsarge, and Barker recalled the weather on 17 August as a “perfect day” as President and Mrs. Roosevelt and their daughter Alice, on board Mayflower, started on time and passed down between the columns of battleships and a division of destroyers. Each battlewagon in turn fired a 21-gun salute just before the presidential yacht passed, and their bluejackets manned their rails, bands played, and marine guards stood to attention. Mayflower came about following the review, and the flag officers and commanding officers of the participating ships and the foreign naval attachés then boarded the vessel and paid their respects to the chief executive.

President Roosevelt intended to project American naval power into European waters, especially within the Mediterranean Sea, and directed the Navy to deploy several squadrons across the Atlantic during the winter of 1903 and 1904. The ships gathered and trained in the Caribbean, and on 9 May 1904 reached Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, and began coaling. The ships mostly had fouled bottoms and required work in shipyards, but the Navy directed Barker to deploy the battleship squadron, consisting of Kearsarge -- again his flagship -- Alabama, Illinois, Iowa, Maine (Battleship No. 10), and Missouri (Battleship No. 11), across the Atlantic to Lisbon, Portugal. Illinois, Maine, and Missouri suffered accidents, however, that delayed their arrival, halving Barker’s strength. Missouri’s steering gear broke down with the fleet carried out target practice on 11 March 1904, and Illinois and Missouri collided. Missouri had only just been commissioned on 1 December 1903, and during the court of inquiry Barker surmised that her “comparative slowness in making the necessary signals” stemmed in large part from the inexperienced crew. Ill fortune hounded Missouri and while the ship conducted target practice on 13 April an explosion in the port 12-inch gun in her rear turret killed 36 men. Some of the survivors swiftly prevented the fire from spreading to her magazines and saved the ship, and Missouri completed repairs at Newport News, Va.

Meanwhile, Olympia shifted from the Caribbean Squadron on 20 April when Rear Adm. Theodore F. Jewell, Commander European Squadron, broke his flag in her at Pensacola, Fla. Jewell refueled the three ships of the squadron -- Olympia, Baltimore (Cruiser No. 3), and Cleveland (Cruiser No. 19) -- at St. Thomas because of insufficient coal stocks at Guantánamo Bay. The cruisers then set out for Horta, where they coaled on 28 May, and then prepared to resume their voyage to Lisbon, but they received word of a crisis looming across the Atlantic.

Moroccan Sharif Mulai A. er Raisuni, known as “The Raisuli” to most Americans, kidnapped a man and a boy he erroneously believed to be U.S. citizens, Ion H. Perdicaris and Cromwell O. Varley, from Perdicaris’ villa in Tangier, Morocco, on 18 May 1904. The British, French, Germans, and Spanish all vied for control of Morocco, alternatively presenting extravagant gifts to Sultan Abdelaziz, in the hope of gaining coaling concessions for their ships. Raisuni apparently resented the foreigners’ influence and sought to embarrass the sultan, demanding a ransom for the safe return on his hostages. “Situation serious,” U.S. Consul Gen. Samuel R. Gummeré telegraphed to the State Department the following day, “Request man-of-war to enforce demands.”

The U.S. initially sent the South Atlantic Squadron, Rear Adm. French E. Chadwick in command, to Tangier to compel the release of the hostages. Chadwick broke his flag in Brooklyn (Cruiser No. 3) and the squadron, also consisting of Castine (Gunboat No. 6), Machias (Gunboat No. 5), and Marietta (Gunboat No. 15), set sail on easterly courses, put in to Santa Cruz at Tenerife in the Canary Islands briefly on 28 May, and reached Tangier on 30 May. On that day, Brooklyn landed a detachment of a dozen marines equipped with side arms led by Capt. John T. Myers, USMC, who secured the U.S. Consulate and Ellen Perdicaris, the Greek expatriate’s wife. Chadwick regularly sent messages informing Barker of these tumultuous events. Meanwhile, Jewell received orders to reinforce Chadwick and directed the European Squadron to set course for Tangier. Olympia, Baltimore, and Cleveland reached that port on the first of the month, raising the number of U.S. warships there to seven.

The European powers also took a keen interest in the proceedings. The British initially did not consider intervening and the Foreign Office advised Sir Arthur Nicolson, their Minister at Tangiers, that as a “general rule such demonstrations tend rather to make negotiations for the release of the captives more difficult.” As the crisis unfolded, however, Nicolson requested that they should deploy some strength as a precautionary measure and Adm. Sir Compton E. Domville, RN, Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean Fleet, dispatched battleship Prince of Wales from Gibraltar, which arrived at Tangier on 7 June. The British directed additional ships originally scheduled to deploy to Rapallo, Italy, to “remain in port until further orders.” The French also monitored the incident and their foreign minister, Théophile Declassé, queried the French minister in Morocco concerning the possibility of involvement. C. Camille Pelletan, that country’s Minister of Marine, cabled Vice Adm. Camille A.L.F. Gigon, Maritime Prefect at Toulon, about sending one or two warships to Tangier, but the French opted not to interfere.

Rumors circulated among the Spaniards about American plans to seize Tangier as a coaling station, and delegates to the Cortes Generales (senate) debated dispatching men-of-war to Moroccan waters. Prime Minister Antonio M. y Montaner deftly skirted the issue by alluding to protecting Spaniards -- and Spanish colonial rights -- without committing to sending the ships. The presence of Barker’s battleships anchored in the Tagus increasingly roused Portuguese fears of U.S. expansionism, and the Navy instructed the admiral to lay to off Lisbon until 16 June, but extended his stay for two days. Their time at that port proved less arduous than feared as the admiral and his officers made the rounds of repeated soirees, including a dinner ashore for Portuguese King and Queen Carlos I and Amélie and members of the court on 2 June. Barker diplomatically observed that the queen so “charmed” him that he did not notice whether she wore jewels. The admiral added that he and his men “were pretty well tired out when all was over” before they set out for Gibraltar.

The audacity of the kidnapping and the affront to the U.S. incensed many Americans. “It should be clearly understood,” Hay cabled Gummeré on 9 June, “that if Mr. Perdicaris should be murdered, the life of the murderer will be demanded, and in no case will the United States be a party to any promise of immunity for his crime.” The Navy and the State Department considered plans to land men from the ships and deploy them inland to rescue the hostages. The landing force consisted of two brigades, one from the South Atlantic Squadron and the other from the European Squadron, numbering more than 1,200 bluejackets and marines, equipped with five 3-inch field guns and 14 Colt-Browning M1895 and Gatling machine guns. The ships were to bombard the coastal batteries at the Custom Pier and at the northwest battery, and the marines to storm the custom house and main pier. An advance inland away from the ships’ gunfire support appeared a grim prospect, however, considering the large number of tribesmen Raisuni could potentially summon and the immense logistic problems to be overcome.

President Roosevelt and Secretary of State John M. Hay responded sternly to the situation, the secretary cabling Gummeré on 22 June: “The United States Government wants Perdicaris alive or Raisuli dead. No marine should be landed, however, or custom-house seized without specific directions from the Department.” Joseph G. Cannon, Speaker of the House of Representatives, read the first sentence of the telegram to the delegates gathered at the Republican National Convention at the Chicago Coliseum. The news electrified the delegates and they broke into an uproar, demanding U.S. military action. Cannon (apparently) did not receive the second sentence of the ultimatum, however, and thus the public remained largely unaware of Hay’s cautionary admonition. Olympia hove to off Tangier during most of the incident (1–8 and 11–29 June), interrupting her vigil to coal at Gibraltar (8–11 June). Following a flurry of negotiations Raisuni received the ransom and returned Perdicaris and Varley on 21 June, and on 27 June the ships came about. “It was fortunate for all of us, including the Government and people of the United States” Barker afterward reflected on the participants’ peacefully resolving the crisis, adding that “…it would have cost a pretty penny to reach him [Perdicaris] with a force of sailors and marines.” The motion picture The Wind and the Lion, released in 1975, dramatizes the incident.

The Navy originally planned to send the South Atlantic Squadron into the Mediterranean but instead dispatched Chadwick down the west coast of Africa. The European Squadron spent Independence Day and some days afterward coaling and taking on stores at Gibraltar, where Illinois and Mayflower joined them, and Jewell then took them into the Mediterranean to Trieste in Austria-Hungary. Barker meanwhile deployed his ships into the Mediterranean, Missouri having been delayed by repairs after the collision with Illinois and following the squadron.

Beginning in September 1902, the U.S. Legation at Constantinople (Istanbul) had addressed a note to Ottoman Turkish Sultan Abdul Hamid II requesting that the Sublime Porte grant the same rights and privileges to American educational, charitable, and religious institutions that the Turks granted to a number of the European powers, basing the demand upon the favored-nation clause of the treaty between the U.S. and the Ottoman Empire. The sultan and his representatives repeatedly avoided the issue, however, and in April 1904, the U.S. Minister to Turkey, John G.A. Leishman, reported that the Turks finally refused the request on the grounds that “in regard to the schools and religious institutions, no difficulty being raised on their behalf, there is no reason for their confirmation.” Both governments alternatively postured, and in May Secretary Hay wrote to Leishman that “an imposing naval force will move in the direction of Turkey. You ought to be able to make some judicious use of this fleet in your negotiations within committing the Government to any action”.

The Americans selected Athens, Greece, as a strategic port that brought their ships within a day’s passage of the Dardanelles or Smyrna (Izmir) without making their actions too obvious — and avoiding insulting the sultan. Kearsarge, Alabama, Iowa, and Maine consequently anchored in Phaleron Bay at Piraeus, near Athens (30 June–6 July 1904). Missouri joined them on 3 July, and the American officers again made the rounds of their Greek counterparts, and received King George I on board the flagship on the 4th of July. A number of European diplomats and journalists expressed their concern about the possibility of the crisis escalating. The Russians, in particular, considered the Turks to fall within their sphere of influence and their Ambassador to the United States, Count Arthur P.N. Cassini, protested the battleships’ arrival. Barker nonetheless followed the visit by exercising the ships in the Aegean Sea, but their departure from port backfired when the sultan cancelled an audience with Leishman on 8 July. That day the battleships stopped briefly at Corfu in the Ionian Islands and then entered the Adriatic Sea, where they made port at Trieste (12–24 July). While there typhoid broke out among the men on board Kearsarge, which apparently began during her brief sojourn at Athens, and a number of the ships company convalesced at a hospital ashore.

Jewell sought to make up for the time lost while refueling his ships at Gibraltar and decided against deploying his ships into Greek waters, much to the displeasure of Navy planners and State Department diplomats, who preferred that he do so to reinforce Barker and present a stronger fleet. Jewell elected to make for the Adriatic, but while passing through the Strait of Otranto Baltimore suffered engine trouble and Olympia’s wireless broke down. The European Squadron rendezvoused with Illinois, which had steamed from Gibraltar, and thus reached Trieste a day behind Barker. The fleet then separated again, and the cruisers sailed to Corfu, while Barker signaled “Good Bye” to them and the battleships rounded the Istrian Peninsula and visited Fiume (25–30 July).

The absence of the fleet apparently emboldened the Turks and they twice more refused to grant Leishman an audience, both times scarcely hiding their disdain. The Americans grew increasingly exasperated, and on 16 July the State Department instructed Leishman to inform Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs Ahmet Tevfik Pasha that it “failed to understand the delay in according him [Leishman] the treatment due to the friendly relations of the two countries”, and to demand an appointment at a fixed time and date. The acrimonious tone of these communiqués carried an implicit threat and on 29 July Leishman conferred with the sultan, who told him he would reply on the school question within four days. The State Department decided to play a strong hand, however, and informed the minister that Barker, who took his battleships through the Strait of Messina on 2 August and six days later back to Gibraltar, would be directed to hold his squadron “in readiness subject to orders”. Jewell brought his cruisers to Villefranche, France, where he received similar messages (3–7 August).

Roosevelt meanwhile on 5 August impatiently gathered the cabinet in a special session and ordered Jewell to deploy the European Squadron to Smyrna, and directed Barker to continue to maintain his battleships at Gibraltar. Leishman cabled Hay from Pera (Beyoğlu — a district in Constantinople) on 8 August, noting that the Turks had not replied or apologized, and recommending that “unless strong measures are adopted, matters may continue to drag along indefinitely”. Hay responded that Jewell and his ships steamed en route and would reach Smyrna “in a few days”, instructed him to obtain a satisfactory answer from the Turks before the fleet arrived, but added that if the Ottomans failed to “grant the moderate and reasonable requests of this Government”, then Leishman was to take an indefinite leave and depart on board one of Barker’s ships. These types of actions typically presaged fighting and tensions correspondingly rose, and Leishman pointedly observed that the Turks preferred to negotiate the issue without confronting the fleet. When Hay returned from a meeting with Roosevelt that day, he found Turkish Minister to the United States, Chekib Bey, filled with “great perturbation about the fleet”. Hay attempted to calm Bey but added that the crisis arose largely because of Turkish intransigence. Olympia, Baltimore, and Cleveland visited Smyrna (12–15 August) and the Turks finally capitulated to the Americans’ demands. Barker then came about for U.S. waters, refueling and victualing at Horta (18–20 August) and returning to Menemsha Bight off Martha’s Vineyard, Mass., on 29 August. Jewell subsequently followed, concluding the momentous naval deployment to European waters.

The march of time caught up with Barker and he neared his retirement age, so Rear Adm. Robley D. Evans relieved Barker while the band played Auld Lang Syne during a ceremony on board Kearsarge, on 31 May 1905. “The hauling down” of the admiral’s flag, the Army and Navy Journal observed, “was the occasion for a display of the esteem and appreciation in which he is held by the officers and men of late under his command”. Barker reached the nation’s capital on the night of 1 April, where his wife Ellen had leased a house on Hillyer Street, and was reunited with his family. Rear Adm. Barker died on 30 January 1916 at Washington, D.C., and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

(Destroyer No. 213: displacement 1,215; length 314'4"; beam 31'8"; draft 9'10"; speed 35 knots; complement 132; armament 4 4-inch, 1 3-inch, 12 21-inch torpedo tubes; class Clemson)

Barker (Destroyer No. 213) was laid down on 30 April 1919 at Philadelphia, Pa., by William Cramp and Sons Ship and Engine Building Co.; launched on 11 September 1919; sponsored by Mrs. Barker, widow of the late Rear Adm. Barker; and commissioned on 27 December 1919, Lt. Cmdr. Charles C. Windsor in command.

Barker visited Newport, R.I., beginning on 11 February 1920, and then made her shakedown cruise to Bermuda, putting in to Hamilton at the British colony on 14 February. The ship came about and first visited Charleston, S.C., on 10 March, and three days later Georgetown in that state. Tumultuous events erupted during the fall of the Russian and Ottoman Empires and the ensuing Russian Civil War and Turkish War of Independence, and so Barker received notification of her deployment to Europe. The ship visited Berkley, Va., and Philadelphia on 17 and 19 March 1920, respectively, completing preparations at those ports for her deployment overseas, before sailing on the latter date to join Division 35, U.S. Naval Detachment, Turkish Waters. She crossed the Atlantic and reached Gibraltar on 26 May and on 31 May Messina, Sicily, and then served for several months with the American Relief of Armenia and visited some Turkish ports and places in the Middle East, beginning with Samsun in the Ottoman Empire (Turkey) on 21 June. Barker was reclassified to DD-213 on 17 July 1920.

The destroyer continued a round of voyages that included visiting diverse ports, often embroiled in wars. She crossed the Black Sea and visited Russia (the Soviet Union), rent by the fighting between the Bolsheviks and those who opposed them (often known as the “Reds” and “Whites”, respectively), and visited Sevastopol on 15 September. Barker came about and put in to Constantinople, Turkey, on 17 September, and then returned across the Black Sea and visited Yalta in the Soviet Union on 30 September. The ship then charted a southerly course through the Dardanelles and visited: Piraeus, Greece, on 6 November; followed by Alexandria and Port Said, Egypt, on 9 and 15 November, respectively; Jaffa, Palestine (Israel), on 16 November; Beirut, Lebanon, on 23 November; Smyrna (Izmir), Turkey, and on 27 November. The warship slipped back through the Dardanelles and celebrated Christmas at Constanta, Romania, and rounded out the year by visiting Varna, Bulgaria, on 30 December 1920.

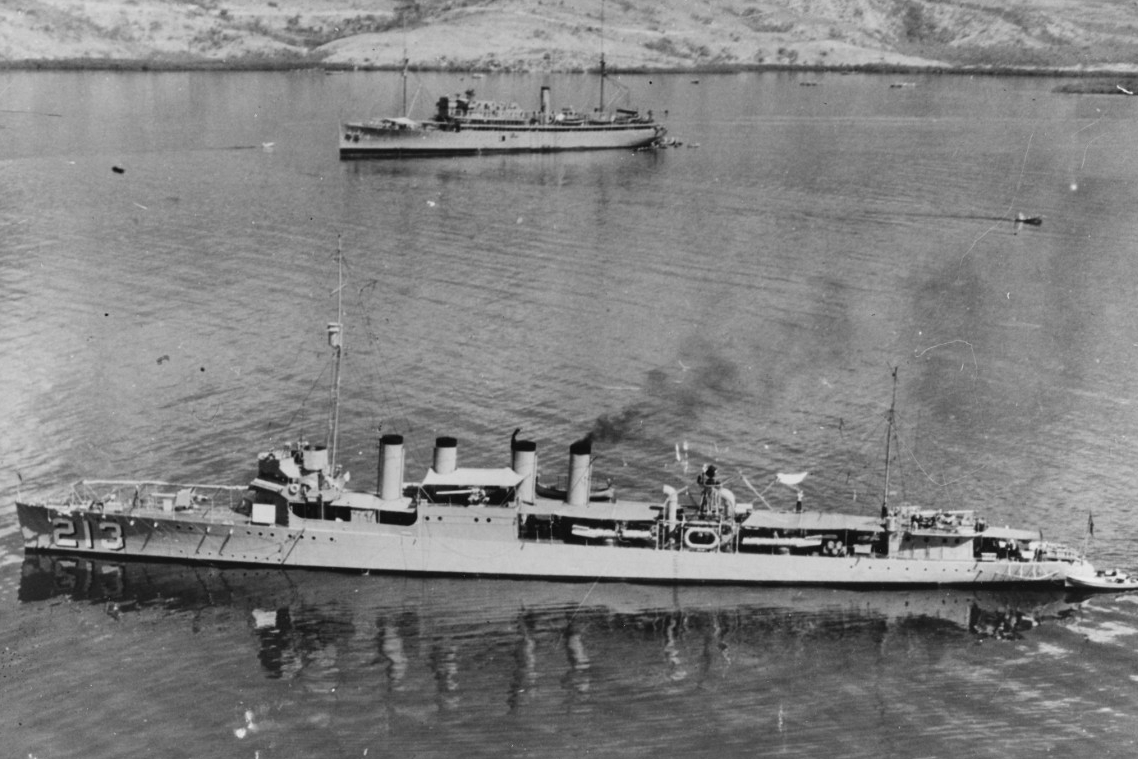

Early in the New Year Barker steamed easterly courses across the Black Sea and put in to Trebizond, Turkey, on 26 January 1921, following that visit two days later by reaching Bat’umi, Russia. The man-of-war then returned to the Mediterranean and visited: Valletta, Malta, on 1 March; Gabes Bay near Tunis, Tunisia, on 12 March; and back to Turkish waters and visited Constantinople and then lay to off some islands in the Sea of Marmara, on 20 March and 5 May, respectively. The ship then turned her prow eastward toward the Orient to commence a four-year tour of duty with the Asiatic Fleet. Barker passed southward through the Suez Canal into the Red Sea and visited: Aden (Yemen — then a separate British colony), on 9 May; Bombay (Mumbai), India, on 16 May; Colombo, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), on 27 May; Batavia (Jakarta), Java, Netherlands East Indies (NEI — Indonesia), on 6 June; Singapore on 16 June; Saigon, Indochina (Vietnam), on 23 June; and Cavite Island in Manila Bay in the Philippines, on 30 June. Barker commenced an annual deployment cycle in which she patrolled Philippine and Asiatic waters, and spent a portion of each year in the Manila Bay area.

Barker thus shaped a course for Chinese waters, operating areas that were to become very familiar to her crewmen and visited: Chefoo (Yantai) on 1 August; Tashik Tan on 9 August; Chefoo again on 12 August; Shanghai on 23 September; and back to Manila on 5 October 1921. After spending the winter in Philippine waters, the ship returned to Shanghai on 10 June 1922. From there Barker made for Chefoo, where she arrived on 11 July, before returning to Cavite on 10 October 1922. The following year Barker turned northward and visited Yokohama and Kobe on 15 and 27 April 1923, respectively. The destroyer returned to Chinese waters and put in to Tsingtao on 9 May; Chefoo on 20 May; Dalniy (Port Arthur — Dalian), Manchuria (China), on 28 August; Chingwangtao (Qinhuangdao) on 15 August; Dalniy again on 28 August; Yokohama on 15 September; Shanghai on 3 October; and so back to Manila on Halloween 1923. Following the usual winter upkeep in Philippine waters Barker resumed her routine across the western Pacific and visited: Hankow (Hankou), China, on 23 April 1924; Shanghai on 5 May; Amoy (Xiamen) on 10 June; the Woosung (Wusong) District in Northern Shanghai on 14 June; Chefoo on 2 July; Shanghai on 22 October; and back to Manila on 31 October 1924.

The ship modified her normal schedule by plotting southerly courses and visited two Dutch East Indian ports: Batavia on 7 March 1925, and Balikpapan on Borneo on 17 March. Barker then showed the flag at a number of seldom visited Philippine islands: Dumaguete on Negros on 19 March; Cebu on 23 March; Batangas on Luzon on 29 March; and then returned to Manila Bay on 1 April. The seasoned destroyer ended her long period of absence from her homeland when she came about from Asiatic waters and departed Manila in May 1925. Barker charted easterly courses and reached Midway Island on 1 June, Pearl Harbor on 9 June, San Diego, Calif., on 21 June, and Balboa at the Panama Canal Zone on 3 July. She then passed through the canal into the Caribbean, reached New York on 17 July, and on 23 July put in to Newport.

Barker served during the next two years with the Scouting Force on the east coast, at times cruising in the Caribbean. The ship therefore carried out training at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, beginning on 25 September 1925. Violence flared in Haiti during this period, and Barker consequently anchored at Gonaives in that troubled land on 20 November, before returning to Norfolk on 26 November. Barker returned to Guantánamo Bay on 4 March 1926; and back to Norfolk on 7 May and on 18 May to New York. The ship returned briefly to the balmy Caribbean waters, stopping at Hampton Roads while en route on 15 September, and then visiting Gonaives on 20 September and returning to winter at Norfolk on 23 November.

Fighting between rival Nicaraguan factions also broke out throughout the decade and the struggling government invited American assistance on more than one occasion. Revolutionary Augusto C. Sandino proved intractable and led guerilla warfare against U.S. marines and the Nicaraguan Guardia Nacional. The ship patrolled off that embattled country (10–31 January 1927) and visited: Blue Fields, Nicaragua, on 10 January; Colón at the Panama Canal on 12 January; and Corinto and the Gulf of Fonseca, Nicaragua, on 14 and 16 January, respectively. Barker wrapped-up her patrols off Nicaragua and put in to Guantánamo Bay on 6 February and three days later returned to Norfolk. Following a brief period of upkeep, the ship trained at Guantánamo Bay, beginning on 15 April, returned to New York on 1 May; and visited Norfolk on 21 May and Newport on the last day of the month.

Thereafter in the spring of 1927, she set out on a tour with U.S. Naval Forces, Europe, carrying out goodwill visits to many European ports. Vice Adm. Guy H. Burrage, who led those forces, noted that the comparatively small size of most of the ports they intended to visit imposed difficulty in sending the flagship, light cruiser Detroit (CL-8), and all of the ships of Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 38, into any given port simultaneously, because of interfering with local shipping. Barker consequently steamed largely in company with Whipple (DD-217), another ship of her Clemson class. The two destroyers crossed the Atlantic and reached Cobh (formerly Queenstown), Ireland, on 9 June 1927, nosed in to Cherbourg, France, on 20 June, and celebrated Independence Day at Gravesend, England (1–7 July). They then visited: Aberdeen, Scotland (9–17 July); Goteborg, Sweden (19–30 July); Memel Territory (Klaipėda), Lithuania (1–5 August); Riga, Latvia (6–12 August); Helsinki, Finland (13–19 August); Tallinn, Estonia (19–24 August); the Free City of Danzig (Gdańsk) (25–28 August); Gdynia, Poland (28–30 August); Kiel, Germany (31 August–6 September); Amsterdam, Netherlands (8–15 September); Brest and Bayonne, France (17–24 September and 26 September–5 October, respectively); before completing voyage repairs at Gibraltar (8 October–3 November). While there they also took part in short range gunnery exercises with Detroit and the other ships of the division. The British loaned their allies a target raft, upon the condition that the Americans were to pay for any alterations or damage to the raft, and following the shooting restore it to its original condition. The approach of a stormy season punctuated by “Laventer” winds compelled the Americans to end the exercises.

Vice Adm. Burrage again observed the comparatively small size of most of the ports along the Mediterranean, and therefore resolved to continue to dispatch the ships in pairs. Barker and Whipple detached and entered the Mediterranean to call at Almería and Barcelona, Spain (4–11 and 12–19 November, respectively). The ships completed work in drydock at Bizerte, Tunisia (21 November–5 December), where the French colonial authorities proved “most cordial” and charged competitively low prices — though the Americans provided the paint. The destroyers next visited Cannes and Villefranche, France (6–12 December and 12 December 1927–11 January 1928, respectively); and Genoa, Italy (11–20 January). They rendezvoused with some of the other ships of DesDiv 38 at Villefranche (20–21 January), and from there visited Gibraltar (24–29 January). Following their brief stay at the British crown colony, the ships crossed the Atlantic for home, stopping at Punta Delgada (1–2 February) and concluding their European cruise when they returned to Guantánamo Bay on 11 February 1928.

The following year Barker passed back through the Panama Canal into the Pacific, and worked briefly out of the west coast until 2 August 1929, when she set out to operate with the destroyer divisions of the Asiatic Fleet. Barker refueled at Pearl Harbor, T.H., on 9 August, and made for the western Pacific, where she steamed primarily in Japanese and Chinese waters, and protected American interests in the latter war-torn country (1929–1932). The unique conditions that existed in China during the internecine wars and confrontations between the rival warlords, who formed military cliques, the Soviets (especially when they fought the Chinese in 1929), and the Japanese, compelled the ships of the Asiatic Fleet to organize and drill landing forces, and to prepare evacuation plans for Americans who lived in China, which were distributed to the ships. The ship put in to: Yokohama, Japan, beginning on 27 August; Chefoo on 2 September; Tsingtao (Qingdao) on 17 September; Shanghai on 25 September; and Cavite Island on 9 October 1929. She returned to Chinese waters in the New Year and visited Swatow (Shantou), beginning on 6 May 1930; Amoy on 11 June; Foochow (Fuzhou) on 30 June; Chefoo on 19 July; Cavite on 15 October; Shanghai on 28 November 1930; and Cavite on 16 January 1931.

The ship won the Gunnery Trophy during the years 1929–1930, but many of the destroyers “have from necessity”, Adm. Montgomery M. Taylor, Commander Asiatic Fleet, reported on 11 July 1932, “been used to perform gunboat duty along the China coast. They were not built for nor are they suitable for the duty. Such duty also interferes with the tactical training and gunnery work and material upkeep of the vessels concerned.”

The Japanese continued to intervene in Chinese affairs and clashed with the Chinese at Shanghai (18–28 January 1932). The crisis escalated and the Japanese then launched what Western journalists dubbed “The Shanghai Incident”: their planes terror bombed Chinese civilians and a mix of soldiers, Kaigun Tokubetsu Rikusentai (Special Naval Landing Troops), armed reservists, and men whom reporters labeled as “Ronin” (agents in civilian garb) attacked Chinese troops, principally men of the 19th Route Army, at the vital port. The Chinese resisted stoutly and both sides poured reinforcements into the fighting. Multiple American and European forces landed to protect their nationals in the city, including soldiers of the Army’s 31st Infantry Regiment, a British infantry brigade, and an estimated three thousand French, and they reinforced men of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps and manned barricades and fighting positions. The 4th Marines took over the defense areas assigned to the U.S. forces in accordance with the approved defense plan on 28 January.

In addition, the Americans and Europeans rushed ships to Chinese waters, which wended their way up the Yangtze and Whangpoo (Huangpu) Rivers. Many sailors could view the fighting, in particular, as the Japanese bombarded a fort in Woosung. Houston landed the marines of her detachment to augment the regiment during what the Asiatic Fleet reported as “the more strenuous period of the State of Emergency in Shanghai” (8 February–29 April). The cruiser also landed some of her bluejackets (4 February–21 March) to relieve a detachment from Borie (DD-215 — 29 January–4 February) that guarded the Riverside Plant of the Shanghai Power Co. The sailors rotated through their shore details, which enabled them to secure some practical training ashore. Some of the men added a macabre aspect to their appearance when they donned gas masks during gas drills. The Asiatic Fleet consequently advised ships on that station to carry “their allowance of gas masks at all times”. Adm. Taylor shifted his flag during this crisis between Houston, Capt. Robert A Dawes in command, and Rochester (CA-2), Capt. William L. Calhoun.

Barker took part in these operations at times with some of the ships of Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 5: Bulmer (DD-222); John D. Edwards (DD-216); Parrott (DD-218); Paul Jones (DD-230); Smith Thompson (DD-212); Pope (DD-225); Pillsbury (DD-227); Truxton (DD-229); and Whipple. Japanese spies tampered with U.S. mail during the crisis, and someone working through the Chinese Post suspiciously opened a letter addressed to Barker and removed several pages. The Chinese and Japanese signed a cease fire on 5 May, by the terms of which most of their troops withdrew from the city. Barker continued to serve in the Far East and returned to Chinese waters during the opening fighting of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1938), protecting Americans trapped in the conflict.

At the beginning of 1941, Barker served with the 57th Division, 29th Squadron, and later operated as part of Task Force (TF) 5 in the Philippines. The ship lay at Tarakan, Borneo, NEI, when the Japanese struck on 8 December 1941, and upon receipt of the news of their onslaught, she began patrolling the surrounding area. During the remainder of December and throughout January 1942, she patrolled and escorted convoys in those waters. During February Barker took part in the abortive attempts to stem the Japanese advance into the Dutch East Indies.

The enemy overran many of the European colonial possessions in the East Indies, and then attempted to seize Banjarmasin, Borneo, and Makassar, Celebes (Sulawesi), which lie on the western and eastern ends of Makassar Strait, respectively, in order to control the strategic passage. They aggressively drove south and gathered an invasion armada at Balikpapan, Borneo, to thrust toward the two ports. An Allied reconnaissance plane sighted these ships as they wended their way southward on 1 February 1942, and alerted the Allies to their peril. In addition, Japanese naval land attack planes of the Takao Kōkūtai (Air Group) bombed the Allied operating base at Surabaya, Java (NEI), on 3 February 1942. Additional naval land attack planes of the 1st Kōkūtai attacked Malang, Java. These raids indicated for the first time that substantial Japanese air forces had deployed southward.

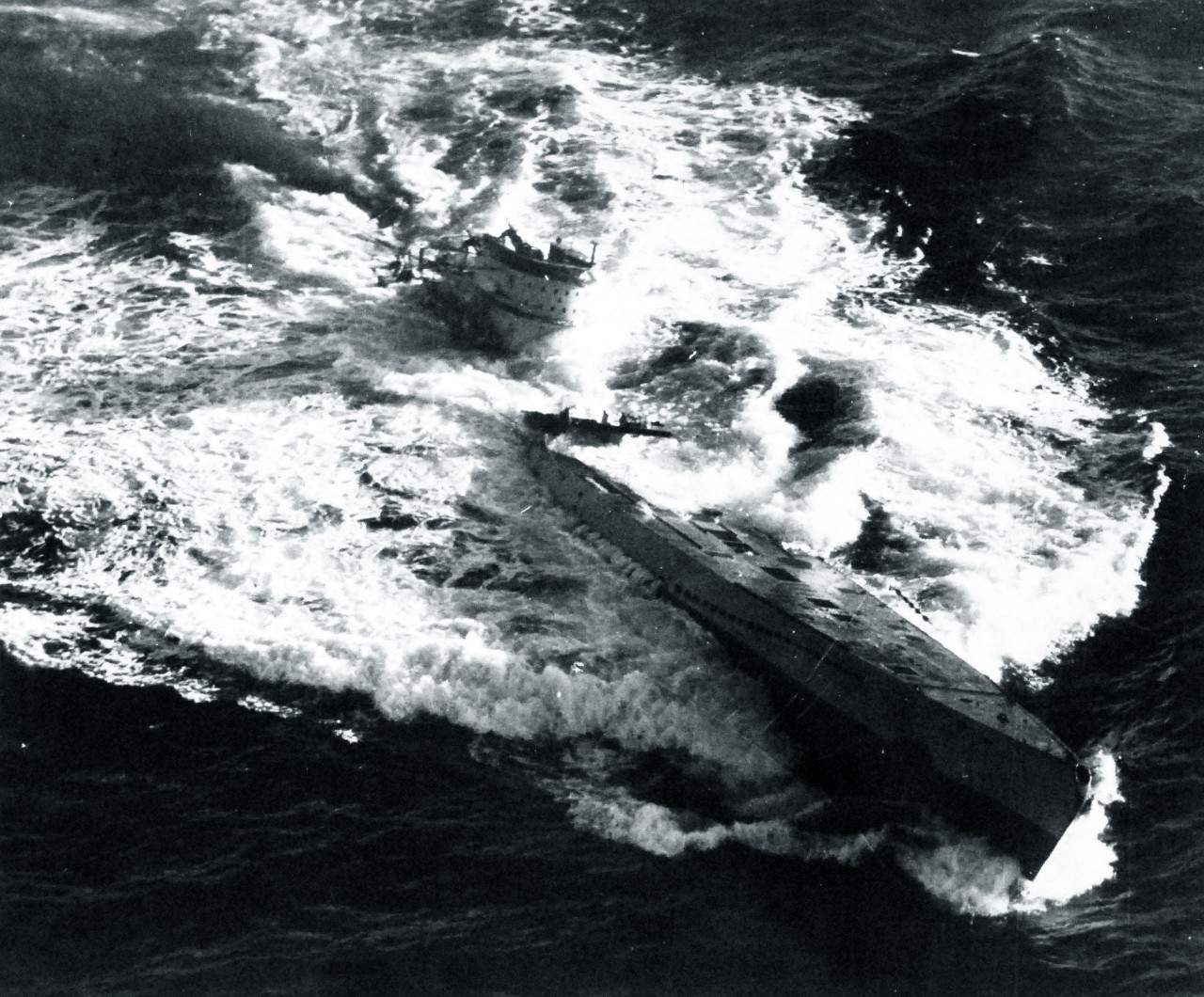

The Allies had meanwhile formed the American British Dutch Australian (ABDA) Command to fight the invaders, however, they paid dearly for years of peacetime neglect. They suffered from severe logistics issues, fought with antiquated equipment, repeatedly failed to obtain and disseminate actionable intelligence, and struggled to meld their disparate forces into cohesive strike forces. In particular, they lacked powerful air support, while their different signaling systems and codes exasperated command, control, communications, and intelligence issues, and they thus often failed to coordinate their actions. These forces included the ABDA Combined Striking Force, Dutch Rear Adm. Karel W.F.M. Doorman, RNN, in command. At midnight on 3 February, Doorman, who broke his flag in Dutch light cruiser De Ruyter, led the available ships of this force out of Bunda Roads at Madura Island, which rises off the northeastern coast of Java. They rendezvoused five miles north of Meyndertssdroogte Light and assumed a formation: De Ruyter led Houston, light cruiser Marblehead (CL-12), and Dutch light cruiser Tromp, steaming at 700 to 800 yard intervals; U.S. destroyers Barker, Bulmer, John D. Edwards, and Stewart (DD-224) took station to protect the flanks; and Dutch destroyers Banckert, Piet Hein, and Van Ghent followed at the rear.

The Allies’ lack of effective air support continued to cost them dearly and a Japanese plane of the 1st Kōkūtai returning from the air raid against Malang sighted and reported Doorman’s ships off Madura. Japanese reconnaissance flying boats of the Toko Kōkūtai then contacted and shadowed the ships as they attempted to pass up the Madura Strait to attack the Japanese Borneo invasion fleet. On the strength of that intelligence, as many as 36 Japanese Mitsubishi G4M1 Type 1 attack planes and 24 Mitsubishi G3M3 Type 96 land attack planes of the Kanoya, Takao, and 1st Kōkūtais took off to bomb the Allied vessels. Doorman received information concerning the impending aerial assault and relayed word to his ships of the approaching Japanese bombers, when the ships reached a position south of the Kangean Islands near 7°28ʹS, 115°37ʹE, at 0935. At 0949 sailors could see the higher peaks of the islands of Bali and Lombok emerge from the broken clouds as the first of four “V” formations of enemy bombers winged overhead from the east at an altitude of 16,404 feet and began attacking.

The Allied ships manned their battle stations, trained their guns skyward, increased speed, and opened their formation in the hope that they would have more room to maneuver and could avoid the expected rain of bombs. Opening their formation, however, split their fire and reduced their antiaircraft effectiveness, and without radar or fighter air cover they fought at a grave tactical disadvantage. A number of the Japanese planes peeled off from their formation and dropped in altitude to bomb more accurately, and despite the efforts of the American and Dutch gunners, and of bridge watchstanders observing the planes’ attacks and turning their rudders hard over to deftly maneuver away from the falling devices, the Japanese savaged the force. Their bombs damaged Houston and Marblehead, and slightly damaged De Ruyter and Tromp by near-misses. The ships risked further losses without fighter cover and at 1300 Doorman signaled them to come about and they turned to southerly courses through Alas Strait and Lombok Strait. Houston lost Turret III (a third of her 8-inch battery) but continued to carry on the fight and made for Tjilatjap. De Ruyter and the Allied destroyers defensively circled Marblehead as she departed from the fray. Masterful seamanship and heroic effort enabled Marblehead to reach Tjilatjap after the battle, where she offloaded her fallen and wounded. The cruiser’s extensive damage, however, required her to return to the United States for repairs during an epic voyage via Ceylon and South Africa.

The Japanese continued their conquest of the region and during the succeeding days isolated Sumatra and then invaded the oil-rich island during Operation L. The invasion armada, Rear Adm. Shintarō Hashimoto in command, principally comprised two convoys carrying the 229th Regiment of the 38th Division from Cam Ranh Bay in the Japanese-occupied Vichy French protectorate of Annam (Vietnam), Indochina, and set out for Sumatran waters during the second week of February 1942. On 9 February Rear Adm. Jisaburō Ozawa led the Western Covering Fleet, which included a mobile striking force built around aircraft carrier Ryūjō, Rear Adm. Kakaji Kauta in command, from Cam Ranh Bay to protect the invaders. Their planes bombed P1 Airfield near Palembang, Sumatra’s capital, and then paratroops attempted to seize the field and a nearby oil refinery on 14 February. The enemy ships meanwhile made for that area and landed troops that overran Bangka Island, and in the estuary of the Musi River, from which they moved inland.

The enemy attacks broadcast their intentions, and on 14 February Doorman took the ABDA Combined Striking Force from Oosthaven (Bandar Lampung) on southern Sumatra to sea to counterattack the Japanese. As Doorman’s ships -- British heavy cruiser Exeter (68), Australian light cruiser Hobart (D.63), Dutch light cruisers De Ruyter, Java, and Tromp, Dutch destroyers Banckert, Kortenaer, Piet Hein, and Van Ghent, and U.S. destroyers Barker, Bulmer, John D. Edwards, Parrott, Pillsbury, and Stewart -- steamed toward the enemy, Van Ghent ran aground on Bamidjo Reef in Stolze Strait, north of Bangka Island, at 0430. Dutch mariners considered the area notorious for navigational hazards, and Banckert and some of the American destroyer narrowly missed the reef. The grounding irreparably damaged Van Ghent and the Dutch scuttled the destroyer, and her sistership Banckert took off the crew. Doorman planned to move around Bangka and strike the enemy vessels anchored off the Musi River, and as the Allied ships emerged from the strait at about 0800, he ordered them to turn to westerly courses to intercept the Japanese invasion fleet.

A Japanese aircraft, however, mostly likely an Aichi E13A1 Type 0 reconnaissance floatplane or a Mitsubishi F1M2 Type 0 observation floatplane, flying from heavy cruiser Chōkai sighted the Allied ships as they proceeded through Gaspar Strait to the north of Bangka at 0923 on 15 February 1942. The spotter relayed the vital discovery to Ozawa, and he decided to send planes against the Allied ships, and then deploy his ships to deliver the coup de grâce with gunfire and torpedoes.