Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

From Beijing to Annapolis: The Journey of the International Gun

In the summer of 1900, 56 U.S. Sailors and Marines were besieged in Beijing by thousands of Chinese soldiers and countless members of a violent secret group that detested foreign influence known as “Boxers.” The small contingent of American service members were at the Legation Quarter—a three-quarter square mile complex in Beijing reserved for foreign diplomats—as part of a multi-national force, protecting the home to the attachés from 11 foreign nations. Seven other nations also had a protective contingent in place, which brought the total international force defending the Legation Quarter to more than 400. As the siege continued, allied artillery dwindled. The Italians had a 1-pounder, but they were out of shells, and the Americans had a Colt gun that required too much of their limited ammunition. As the legation began to realize it could be overrun by the Chinese army and the insurgent Boxers, something desperately had to be devised to return fire.

U.S. Navy Gunner’s Mate First Class Joseph A. Mitchell and Herbert Squiers, the U.S. legation’s secretary, came up with an idea: build a piece of artillery that used the cylinder of a pump as a cannon barrel. As they began to experiment with the crude device, a stroke of luck changed their original plans. Chinese Christian refugees, who were sheltering in the Legation Quarter, discovered a cannon barrel lying in a pile of junk. When it was recovered, it was initially reported to be made of bronze or steel, but was what Mitchell later described as just a “mass of rust and dirt.” Nonetheless, Mitchell went to work, cleaning and scraping the cannon barrel to ensure it would fire properly. Once the barrel was cleaned up to Mitchell’s satisfaction, it was secured to a heavy pole. However, it didn’t work. In another attempt, the gun carriage from the Italians 1-pounder was taken, and the refurbished barrel was secured to the carriage with a rope. With the makeshift cannon seemingly in place, ammunition was the next big obstacle. Earlier, when the Russian contingent arrived at the Legation Quarter, they brought a chest of 3-inch shells; however, they apparently had a lieutenant in charge who forgot the cannon to fire the shells. When the siege commenced, the Russians, abruptly, threw the shells down a well to prevent them from falling into Chinese hands. The shells were ultimately recovered but were too large for the refurbished, narrow barrel. Mitchell’s solution was to first remove the shells from their casing, then ram them into the barrel. Thus, the “International Gun” was born. It was made of material from Russia and Italy and manned primarily by American gunner Mitchell, who later received the Medal of Honor for his actions during the siege.

On July 8, the International Gun fired its first shot at a Chinese battery about 240 yards north of its position with the projectile soaring over the enemy battery and landing in the Imperial City of Beijing. Its second shot was woefully short, but the third smashed into the battery, prompting the Chinese to reply with a barrage of gunfire. Over the course of the 55-day siege, Mitchell continually fired his makeshift gun from multiple positions in the Legation Quarter to make the Chinese believe the legation possessed an ample amount of artillery. In addition, moving the gun was out of necessity because it produced a lot of smoke which drew Chinese fire. Although the gun lacked either sight or accuracy and could not fire effectively at long range, it caused enough damage to prevent the legation from falling to the Chinese. On the night of Aug. 13, as an estimated 20,000 foreign troops were set to converge on Beijing to relieve the international contingent, the Chinese mounted their strongest attack. During the battle, Mitchell continually fired his gun at multiple positions to hold the Chinese at bay. Ultimately, a bullet shattered his right arm during the fight, but his actions were enough to fend off the final Chinese push. The next day, the recently arrived 20,000 foreign troops relieved the battle weary multi-national force at Legation Quarter.

After the Legation Quarter was secured, the Americans had hoped to take the International Gun home. In the end, through diplomacy, they agreed to leave it in Beijing on the condition that it be placed at the base of the monument to Baron Clemens von Ketteler, a German diplomat that was killed during the siege. However, over time, the International Gun was stripped, and only the cannon barrel was left in the Legation Quarter. In July 1901, Army Capt. John H. Reeves asked Secretary Squiers if the Navy had laid claim to the cannon barrel. He replied that it had not, and with Squiers’s permission, the International Gun was transported to Nagasaki, Japan. From there, it was transported to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York.

When he heard about the location of the International Gun at West Point, Cmdr. Bowman H. McCalla, who had commanded Sailors previously during the Seymour Expedition in China, wrote a letter to the Secretary of the Navy: “I can hardly believe that this naval gun, preserved and used by a detachment from the Navy, before the arrival of our Army at Peking [Beijing], is to be added to the museum at West Point, merely because it fell into the temporary possession of a detachment of the Army.” The Navy Department forwarded the letter to the Secretary of War, prompting an investigation. Ultimately, the War Department conceded that the International Gun barrel belonged to the Navy, and on May 23, 1902, it was shipped to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. More than a century later, the barrel still resides at the Naval Academy. For more on how Sailors and Marines survived the siege, see NHHC’s recent publication The Boxer Rebellion: Bluejackets and Marines in China, 1900–1901. It was authored by COD’s Emily Abdow, and its digital version is available for free at NHHC’s website.

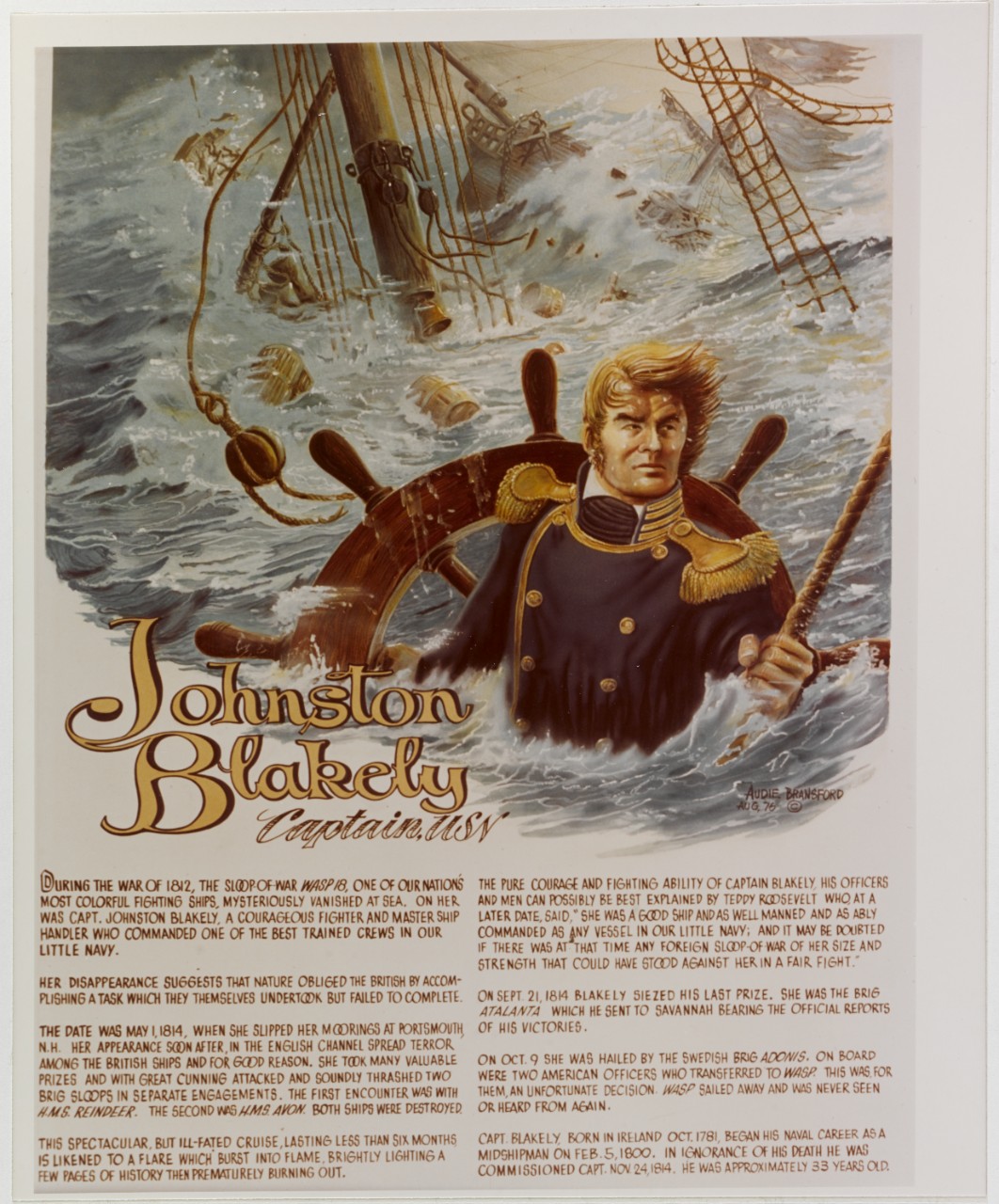

Wasp, Reindeer: War of 1812 Battle

In the late afternoon of June 28, 1814, sloop-of-war Wasp, with Master Commandant Johnston Blakeley in command, encountered 21-gun HMS Reindeer, 225 miles west of Plymouth, England. Reindeer was under orders to engage the deadly American ship that had destroyed multiple British ships—five up to that point during the War of 1812. The battle lasted only 19 minutes, but during that brief span of time both sides traded a barrage of broadsides before the ships came into direct, physical contact. Several times, Reindeer’s crew tried to board Wasp, but the American crew repulsed them on each occasion. In the end, it was Wasp’s crew that boarded the British ship. After they boarded, Reindeer’s commander, William Manners, continued to urge his crew to fight back, but he was ultimately killed by a musket shot from Wasp’s rigging. Once onboard, the Americans swarmed the British crew and drove them below deck. The British commander’s clerk, who was one of the last remaining living officer’s onboard Reindeer, eventually surrendered to the American crew. The crew of Wasp took the surviving British sailors as prisoners, and after deciding the ship was too damaged to take as a prize, burned it.

Wasp suffered 26 casualties with 11 killed in action. Reindeer had 25 killed and 42 wounded. Wasp suffered six hits to its hull and some of its rigging was shot away, but the ship was still operational. After taking prisoners onboard and watching Reindeer explode, Wasp hoisted its sails for L’Orient, France. While en route, the damaged Wasp managed to take two more prizes—112-ton brig Regulator on Independence Day 1814 and 151-ton schooner Jenny two days later. Not long thereafter, Wasp entered L’Orient for repairs, provisions, and to care for its wounded.

Wasp remained in L’Orient until it was put to sea again on Aug. 17, 1814. On its third day underway, Wasp captured the brig Lettice and the following day took another enemy ship, Bon Accord. Early in the morning of Sept. 1, the American ship spotted a convoy of 10 ships escorted by the 74-gun, ship-of-the-line Armada. Wasp made way toward the convoy and singled out brig Mary, which was quickly taken. The crew took its crew as prisoners and burned the ship. Wasp then attempted to take another ship in the convoy, but Armada drove it off. That evening, Wasp’s crew spied another sail on the horizon and gave chase. By early evening, it had 18-gun, 477-ton brig Avon within range and opened fire. The British ship returned fire for about a half an hour, after which its guns went silent. When Wasp did the same and called for the ship’s surrender, the British answered with another cannonade. Wasp once again opened fire on the ship. Some broadsides later, Avon's guns fell silent once more, and Wasp repeated the call for surrender. Avon, at this point, was a badly battered hulk and had no choice but to comply. However, just as Wasp began to lower a boat for the prize crew, a lookout sighted another enemy brig. Wasp's crew manned their battle stations immediately in hope of taking the newcomer as well. Just then, two more British ships appeared on the horizon, and Wasp was forced to give up the destruction of Avon to save itself. The lead British ship hauled in close to Wasp’s stern and fired a broadside into Wasp’s rigging that considerably damaged its sails and running rigging. Then, the British ship halted the engagement and rendezvoused with the other two ships following it and the sinking Avon. Wasp subsequently departed the area.

The American warship continued to wreak havoc on the British merchant marine. On Sept. 12, it encountered another enemy brig and scuttled it, and two days later, it sank the brig Bacchus. On Sept. 21, 8-gun brig Atlanta came into contact with Wasp, and it, too, suffered the humiliation of capture. Deemed too valuable to destroy, Atlanta was taken as a prize and sent to Savannah, Georgia. From the time Wasp and Atlanta parted company, nothing more was heard from the gallant American ship. Wasp was last seen by Swedish brig Adonis about three weeks after the capture of Atlanta and was said to be headed for the Caribbean. It is believed that Wasp sank in a storm with the loss of all hands.

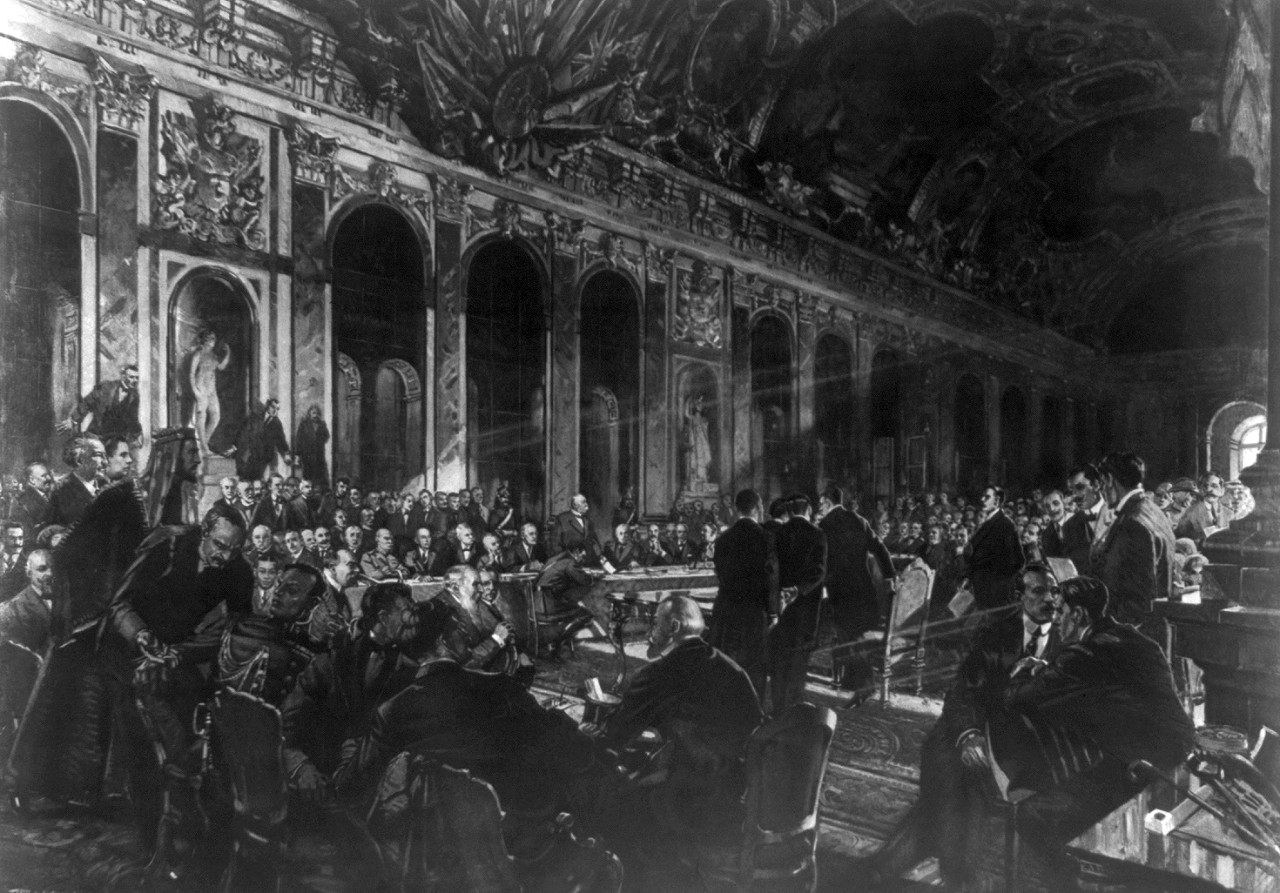

Treaty of Versailles

On June 28, 1919, the Treaty of Versailles was signed, ending World War I. The signing was five years to the day that Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated at Sarajevo, Bosnia, starting the war. Ten days after the treaty, the German High Seas Fleet steamed into the Firth of Forth between parallel lines of the Allied Grand Fleet Ships. The German ships were to be interned at a neutral port, but were instead interned at Scapa Flow, Scotland, the Grand Fleet’s anchorage during the war, upsetting the German navy. All naval aircraft were collected and immobilized in German bases. The German navy was limited to six battleships, six cruisers, 12 destroyers, and 12 torpedo boats. Submarines were outlawed under the treaty.

Negotiations for the treaty were complicated. Although there were 30 nations that participated, the representatives from the UK, United States, France, and Italy dominated the proceedings that led to the formulation of the Treaty of Versailles. The UK, France, and Italy fought together as the Allied Powers during the “Great War.” The U.S. entered the war in April 1917 as an Associated Power. While it fought alongside the Allies, the U.S. was not bound to honor preexisting agreements among the Allied Powers focused on postwar redistribution of territories. President Woodrow Wilson strongly opposed many of these arrangements, including Italian demands on the Adriatic.

Treaty negotiations were also weakened by the absence of other important nations. Russia had fought as one of the Allies until December 1917, when its new Bolshevik government withdrew from the war. The Bolsheviks’ decision to renounce Russia’s outstanding financial debts to the Allies and to publish the texts of secret agreements between the Allies concerning the postwar period angered the Allies. The Allied Powers refused to recognize the new Bolshevik government and thus did not invite its representatives to the Paris Peace Conference in January 1919. The Allies also excluded the defeated Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey, and Bulgaria).

According to French and British wishes, the Treaty of Versailles subjected Germany to strict punitive measures. The treaty required the new German government to surrender approximately 10 percent of its prewar territory in Europe and all of its overseas possessions. It placed the harbor city of Danzig (now Gdansk) and the coal-rich Saarland under the administration of the League of Nations, and allowed France to exploit the economic resources of the Saarland until 1935. It limited the German army and navy in size and allowed for the trial of Kaiser Wilhelm and a number of other high-ranking German officials as war criminals. Under the terms of the treaty, the Germans accepted responsibility for the war and the liability to pay financial reparations to the Allies. The Inter-Allied Commission determined the amount and presented its findings in 1921. The amount they determined was 132 billion gold Reichmarks, or 32 billion U.S. dollars, on top of the initial $5 billion payment demanded by the treaty. The Germans grew to resent the harsh conditions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles, which many speculate was a major catalyst for World War II.

Today in Naval History

On June 27, 1950, President Harry S. Truman authorized U.S. naval and air operations south of 38th parallel in support of the United Nation’s call to assist South Korea. Two days earlier, in four main avenues of approach, an armored brigade and six divisions with approximately 89,000 North Korean soldiers poured across the South Korean border. Spearheaded by about 200 Soviet T-34 tanks and 120 fighter and ground-attack aircraft, along with heavy artillery and with the advantage of tactical surprise, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s military quickly overwhelmed the 38,000 Republic of Korea troops in the northern part of South Korea, who had no tanks, no anti-tank weapons, no air support, not much training, and zero warning. The armored brigade and two North Korean divisions (3rd and 4th Infantry Divisions) marched directly toward the capital city of Seoul, only 30 miles south of the 38th parallel. Meanwhile, two other divisions (1st and 6th Infantry Divisions) attacked farther west before syphoning into Seoul, while the 7th Infantry Division attacked through the central mountains and the 5th Infantry Division attacked southward along the South Korean east coast. Initially, elements of the North Korean army entered Seoul but did not meet their goal of a quick surrender and disintegration of the South Korean army. Instead, remnants of the Seoul-based army formed a defensive line south of the Han River and on the east coast. However, after a brutal fight, Seoul fell to the North Korean army the following day. It was the first of four times the city would change hands during the Korean War.

After evacuating about 1,600 U.S. citizens and friendly foreign nationals from Seoul on June 29, USS Juneau (CLAA-119) and USS De Haven (DD-727) fired the first naval shore bombardment of the Korean War in the vicinity of Samchock, South Korea, destroying multiple enemy shore installations. A few days later, USS Valley Forge (CV-45) and HMS Triumph participated in the first carrier action of the war. Outnumbered and outgunned, South Korean troops battled desperately against tides of invading North Korean soldiers. Waves of Douglas AD Skyraiders and Vought F4U Corsairs struck the North Korean airfield at Pyongyang while Grumman F9F-2 Panthers flew top cover. Tons of bombs from the attacking American planes pounded hangars, fuel storage areas, parked Russian-built aircraft, and railroad marshalling yards. Meanwhile, the escorting Panthers downed multiple Soviet-built Yak-9 aircraft. However, despite attempts to interdict the steady flow of enemy troops, the North Koreans steadily pushed the South Koreans back into a defense perimeter around Pusan (Busan today).

The first several months of the war were characterized by armies advancing and retreating up and down the Korean Peninsula. After the front stabilized at the Pusan perimeter, Gen. Douglas MacArthur surprised the North Koreans in September 1950 with an amphibious landing at Inchon behind North Korean lines, forcing the North Koreans to retreat behind the 38th parallel. The following month, the United Nations—urged by the United States—approved the movement of UN forces across the 38th parallel into North Korea in an effort to unify the Korean Peninsula under a non-communist government. In spite of threats issued by the Chinese government, UN forces moved toward the Yalu River, marking the North Korean border with Manchuria, China. Discounting the significance of initial Chinese attacks in late October, MacArthur ordered his forces to launch an offensive to the Yalu. In late November, the Chinese counterattacked in full strength, pushing UN forces back south of the 38th parallel and ultimately seizing Seoul again.

By early 1951, the Chinese offensive lost most of its momentum and UN troops retook Seoul, advancing back to the 38th parallel. The Korean War at this point was a “back and forth” fight with battle lines continually changing. By June, the Chinese/North Korean armies had grown to 1.2 million soldiers despite suffering about 500,000 casualties. UN casualties had amassed to more than 100,000, and its troop strength was around 750,000. From July 1951 until the end of hostilities, the Cold War conflict was essentially a stalemate. President Harry S. Truman’s administration subsequently abandoned plans to reunite North and South Korea and instead decided to pursue limited goals in order to avoid the possible escalation of the conflict turning into a third world war involving China and the Soviet Union.

On Dec. 2, 1952, newly elected President Dwight D. Eisenhower went to Korea, and after visiting troops, their commanders, and South Korean leadership, sought an end to hostilities through diplomacy. Although peace negotiations had been ongoing since 1951 without much results, on July 27, 1953, an armistice was signed at Panmunjom (a tiny village located on the North and South Korean border) by officials from the UN, North Korea, and China. The armistice ended organized combat operations, left Korea divided, and is still in place today.

From the U.S. Navy’s perspective, due to neither North nor South Korea having a formidable navy, the war featured few naval battles, and vessels from the UN had undisputed control of the sea surrounding Korea. Gunships were used for shore bombardments, and aircraft carriers provided aerial support for boots on the ground. For most of the war, UN navies patrolled the west and east coasts of North Korea, sinking supply and ammunition ships and denying the North Koreans the ability to resupply from the sea. Aside from the occasional gunfire from North Korean shore batteries, the biggest danger to Navy ships were magnetic mines. During the war, the U.S. Navy lost five ships to mines.

During the so-called “Forgotten War,” the United States suffered more than 36,000 fatalities. Approximately 2 to 3 million civilians were also killed, and in wake of the war, South Korea was reduced to rubble. After the armistice was signed, more than 1 million North Koreans fled to South Korea. Many families were forever torn apart by the war. Seven U.S. Navy Sailors and 42 Marines were awarded the Medal of Honor for their gallant actions.