Seaplanes: The Beginning

David Alman

The first true seaplanes, built by the Glenn Curtis company in 1911, started a revolution in aircraft performance. With their clean, sleek lines, and lack of landing gear weight, seaplanes held many of the early speed and range records. Additionally, the ability to land on water was a good insurance policy given the unreliable engines of the day. Two of the three aircraft the Navy first purchased in 1911 were floatplanes, and the third was later converted to one. In 1912, the Navy began experiments associated with seaplane performance, and by 1914 a project was underway to build a long-endurance seaplane for a flight across the Atlantic. World War I interrupted the endeavor.[1]

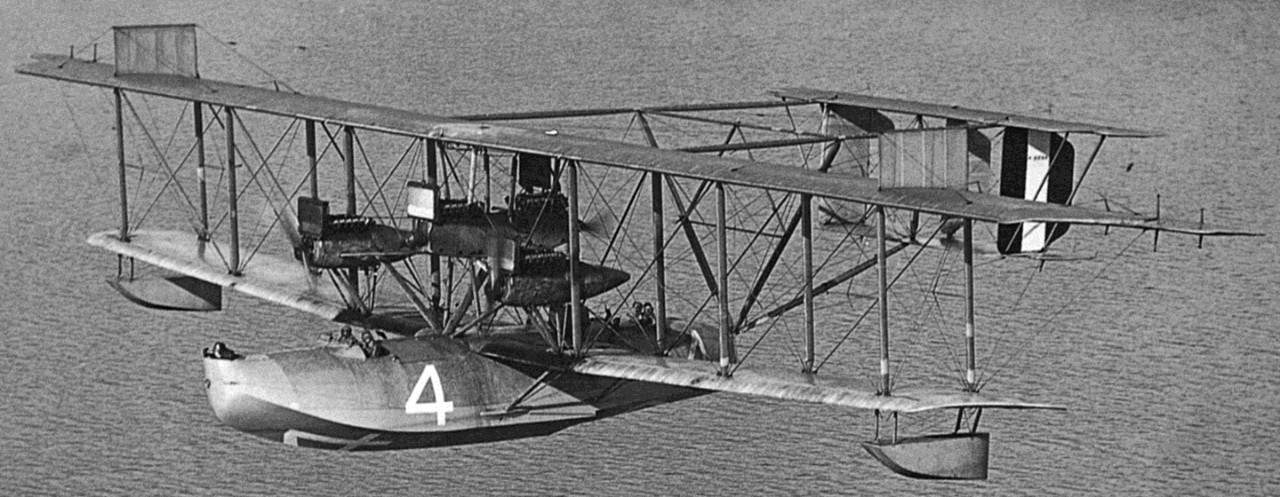

With America’s entry into the War in 1917 came the Navy’s seaplane combat debut. The long-endurance seaplanes were the platform of choice for conducting anti-submarine warfare patrols. The first Navy aircraft to arrive in Europe were Curtiss HS-1 seaplanes in October of 1917. Operational flights commenced from Le Croisic, near St. Nazaire, on November 3rd, 1917. These patrolling seaplanes were the first to greet the soldiers of the American Expeditionary Force as they approached France – many came to know the seaplanes as the sight of safety. Seaplanes also operated out of the British Isles and Italy, where Ensign Hammann was awarded the Medal of Honor. The last operational flight escorted President Wilson’s convoy to France for the Paris Peace Conference[2]

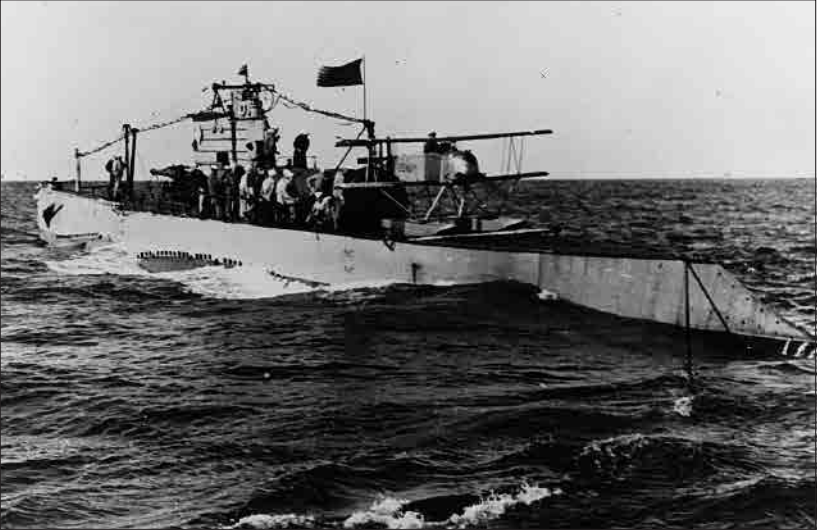

By the early 1920s Navy leaders shifted attention to smaller aircraft capable of operating with the fleet and conducting offensive actions against the enemy. Many of these aircraft were seaplanes, also. The 1920s saw numerous operational experiments that were to prove relevant during war. Eighteen PT seaplanes of Torpedo and Bombing Squadron 1 carried out the first mass torpedo practice against a warship in 1922. Later that year, a PT Seaplane piloted by Cmdr. Kenneth Whiting made the first catapult launch from the USS Langley. In 1926, the Navy marked another seaplane first when the submarine S-1 surfaced, launched a stowed seaplane, recovered it, and submerged.[3]

During the 1930s the first monoplanes developed for carrier operations came into service. Engineering advances allowed land or carrier based planes to achieve higher performance than ever before – it was the beginning of the seaplane’s end. Nevertheless, Navy planners, particularly those tasked with planning against Japan, believed the seaplanes to still be essential for any campaign. Much of the debate over War Plan Orange centered around the inability of the U.S. Fleet to effectively surveil vast expanses of ocean, especially given cruiser shortages.[5] Planners feared that the Fleet could be taken by surprise and destroyed by an inferior force without effective reconnaissance.

In 1933, the Navy awarded a contract to Consolidated that turn out the PBY Catalina. Promised with the coveted thousand-mile range, the Catalina solved the Navy’s scouting problems. With their long-range, large-payload, and water-landing capability, some officers saw other uses for the flying boats. Ernest King in particular pushed for a seaplane striking force.

As War approached, however, the seaplanes slowly lost their role as a striking force. Aircraft performance improvements and shipboard anti-air defenses meant the lumbering seaplanes would not survive in offensive attacks. Land-based bombers such as the B-17 were increasingly being viewed as the long-range strike weapon.

About the author:

David Alman is a graduate student in Aerospace Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech). His research focuses on electronic warfare, aircraft design, and the relationship between technology and strategy. He has previously worked as a consultant and engineer for a variety of defense organizations. David holds a B.S. in aerospace engineering with highest honors from Georgia Tech. He enjoys reading, swimming, flying, and all things aviation related.

[1] W. H. Sitz, A History of U.S. Naval Aviation, Bureau of Aeronautics. Note 18, 1930. (5-9 and 36-39)

[2] Sitz, (20-30)

[3] Evans and Grossnick, (65-100)

[4] Evans and Grossnick, (89)

[5] War plans for a conflict with Japan were known by their code color, Orange

(This essay, originally titled "Seamaster(y)," was published in three parts in the U.S. Naval Institute's Naval History Blog. This is part one.)