Camp Robert Smalls

1942–1948

On 7 April 1942, the U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Navigation announced the implementation of a plan to integrate Black sailors into general naval service starting on the first of June 1942.[1] This represented a significant compromise between President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox remained opposed to the initiative, an attitude that was reflected in the early days of its implementation.[2] Black sailors would train in an isolated section within the perimeter of Naval Training Station Great Lakes near Chicago, Illinois. Like other camps at Great Lakes, this camp was designed to accommodate 4,500 recruits, with 18 barracks, a drill hall, a recreation building, a dispensary, and other necessary utilities.[3] Secluded from other training facilties, the location also offered multiple opportunities for expansion.[4]

William Baldwin, the first World War II–era Black recruit in the U.S. Navy, poses for a photo with the Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox (left) and Rear Admiral Randall Jacobs (right), chief of Bureau of Naval Personnel. (National Archives and Records Administration [NARA], 535852)

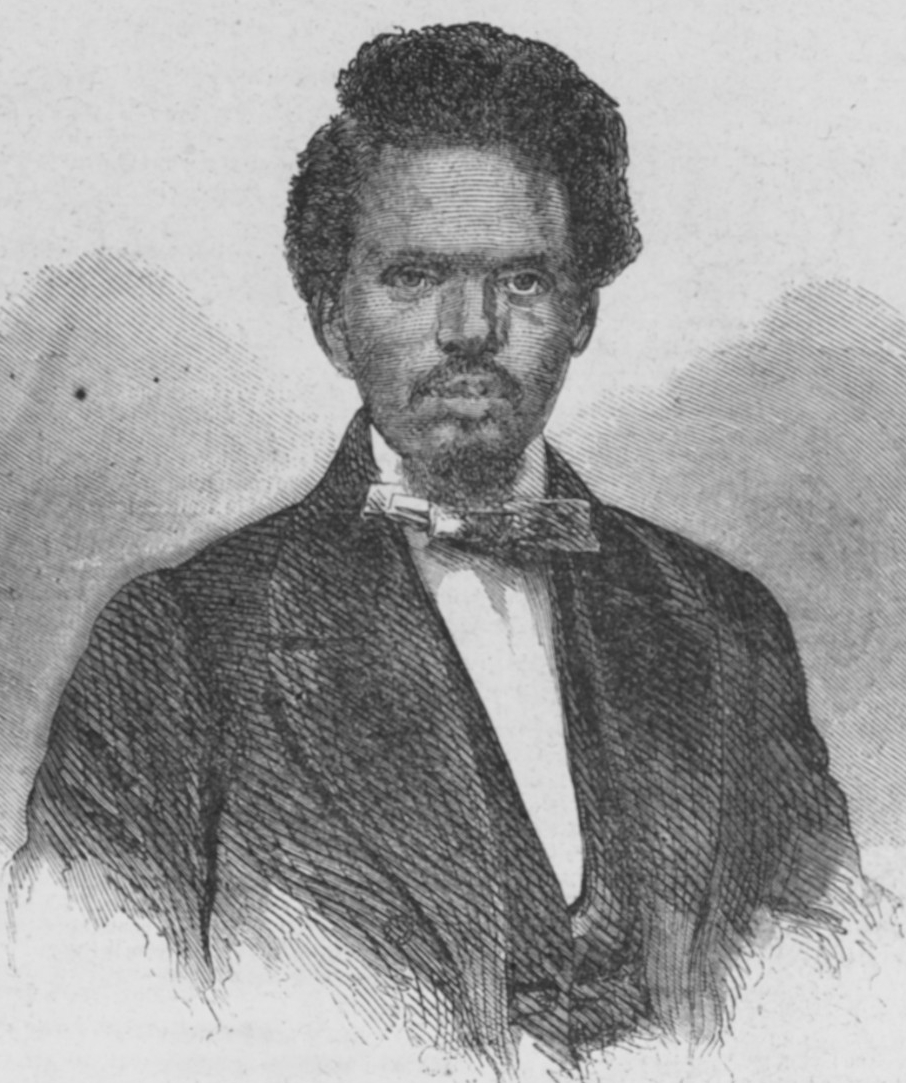

Robert Smalls, c. 1862, engraving from Harper’s Weekly. (Naval History and Heritage Command [NHHC], NH 58870)

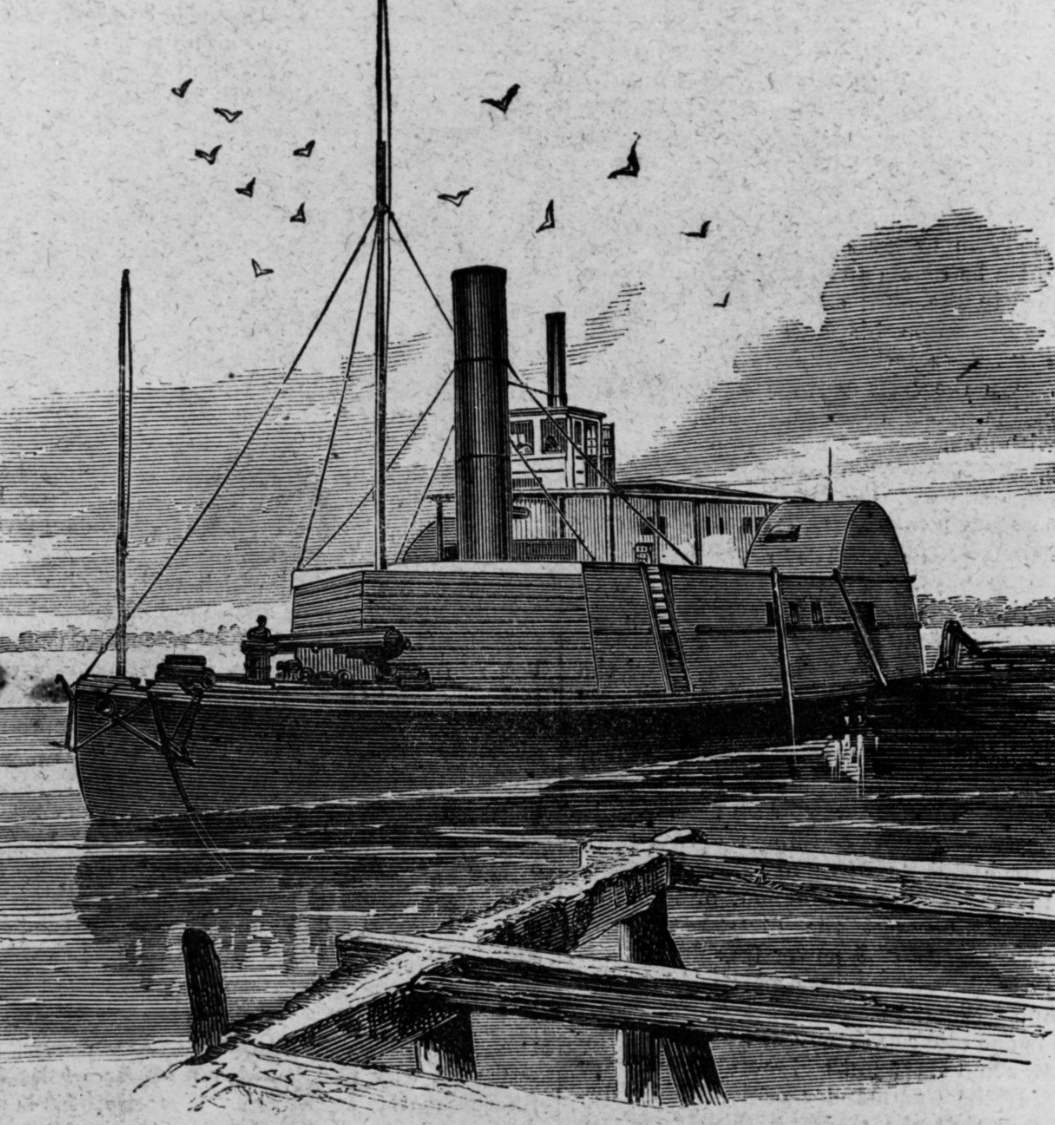

Confederate Army armed transport Planter, c. 1861–62. (NHHC, NH 63568)

The former Camp Barry at Great Lakes was renamed after Robert Smalls, a former slave who had become a Black naval hero during the Civil War. In March 1862, he first commandeered and then piloted a Confederate military transport, CSS Planter, out of Charleston harbor and turned it over to Union forces.[5] Smalls later became a prominent elected representative in South Carolina at the state and federal levels during the postwar Reconstruction era.

Lieutenant Commander Daniel Armstrong, a recalled Naval Reserve officer, was selected command the camp because of his family history. His father had founded Hampton Institute (later renamed Hampton University) in Virginia after the Civil War as a vocational school for the freed slave population. A 1915 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, Armstrong had served in the Navy during World War I and then reverted to reserve status. He had grown up integrally involved with Hampton Institute, but that was not his only qualification. He had written to the Secretary of the Navy in March 1942 with his ideas for the training of Black sailors.[6] He was confident in his approach. He believed in the training program, saying later to the press that “what we're doing here . . . is bending every effort to make these boys as good as any fighting men the U.S. Navy has. The country doesn't yet know what a fine new source of fighting men the Navy has.” [7]

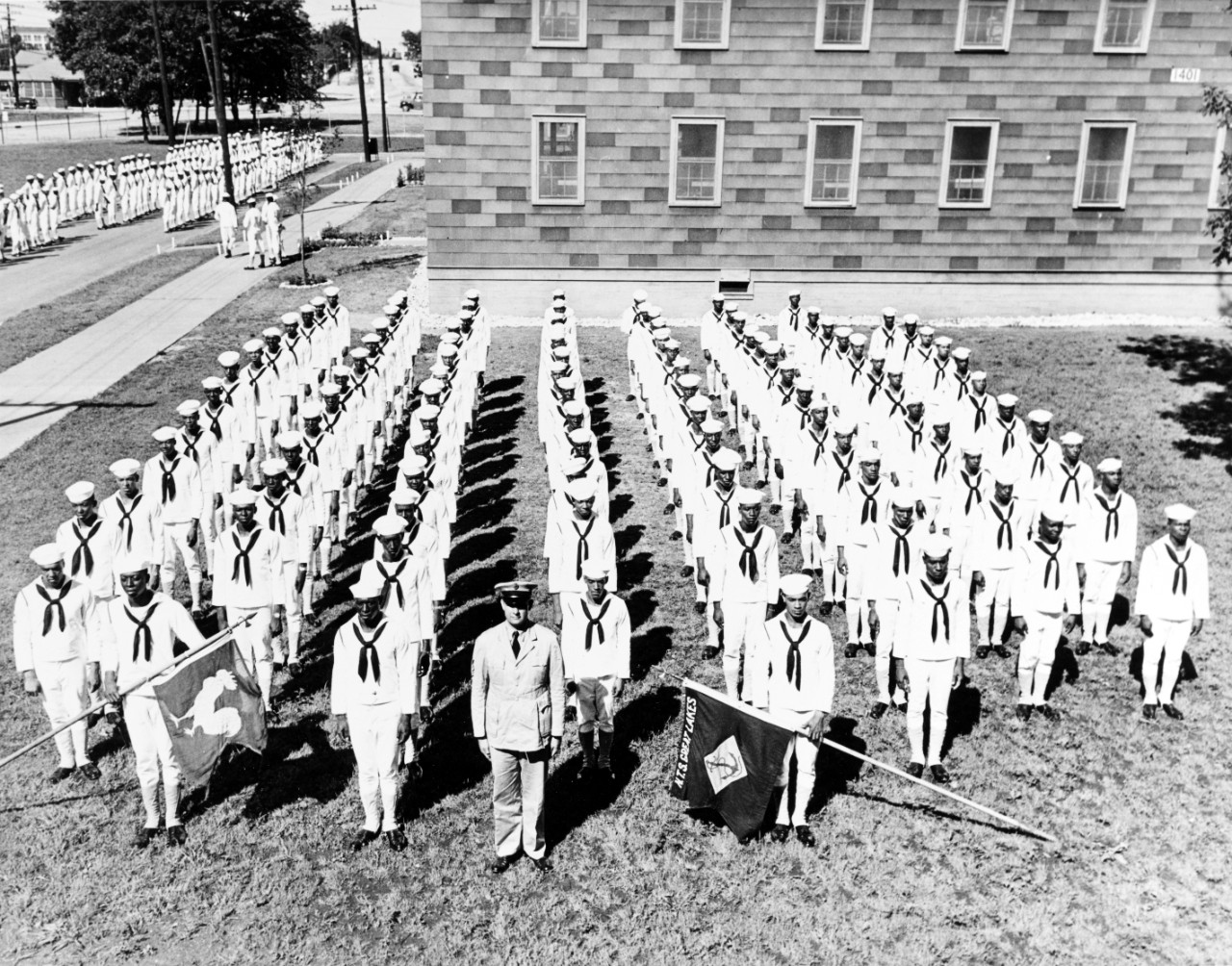

Black recruits line up for inspection at Camp Robert Smalls, Naval Training Station Great Lakes, Illinois, 2 April 1943. (Naval History and Heritage Command [NHHC], 80-G-294731)

The first class of recruits, approximately 277 men, arrived at Camp Robert Smalls in August 1942. When they first arrived, the barracks were still under construction.[8] They graduated eight weeks later as apprentice seamen. Among those first graduates was Edward Estes Davidson, a descendant of Robert Smalls.[9]

Lieutenant Armstrong ran his program at Great Lakes based on the paternalistic philosophy that he had learned from the system that his father built at Hampton. Opinions on Armstrong’s leadership tended to vary based on where the recruits came from—North or South—and their level of education.[10] Some of the educated Black recruits, including Dennis Nelson—who later became one of the Golden Thirteen—resented his philosophy that the training of Black recruits could only be handled on a segregated basis.[11] From experience, recruits believed that “the facilities open to him under segregation are in fact usually inferior as to location or quality to those available others.”[12]

Upon arrival at Camp Robert Smalls, Owen Dodson, who later became a well-known Black playwright, felt fearful of the high fences with barbed wire along the top.[13] Another recruit, Merwin Peters, later recounted: “Everything that went on in Camp Robert Smalls had to do with Camp Robert Smalls. We were ostracized from the rest of Great Lakes.”[14] Yet another contemporary, Sammie Boykin, recalled being reminded daily that black recruits could not be sailors.[15] These frustrations continued to escalate through the course of the war. Armstrong’s policy followed a pattern that the Blacks had learned from experience did not lead to equality.

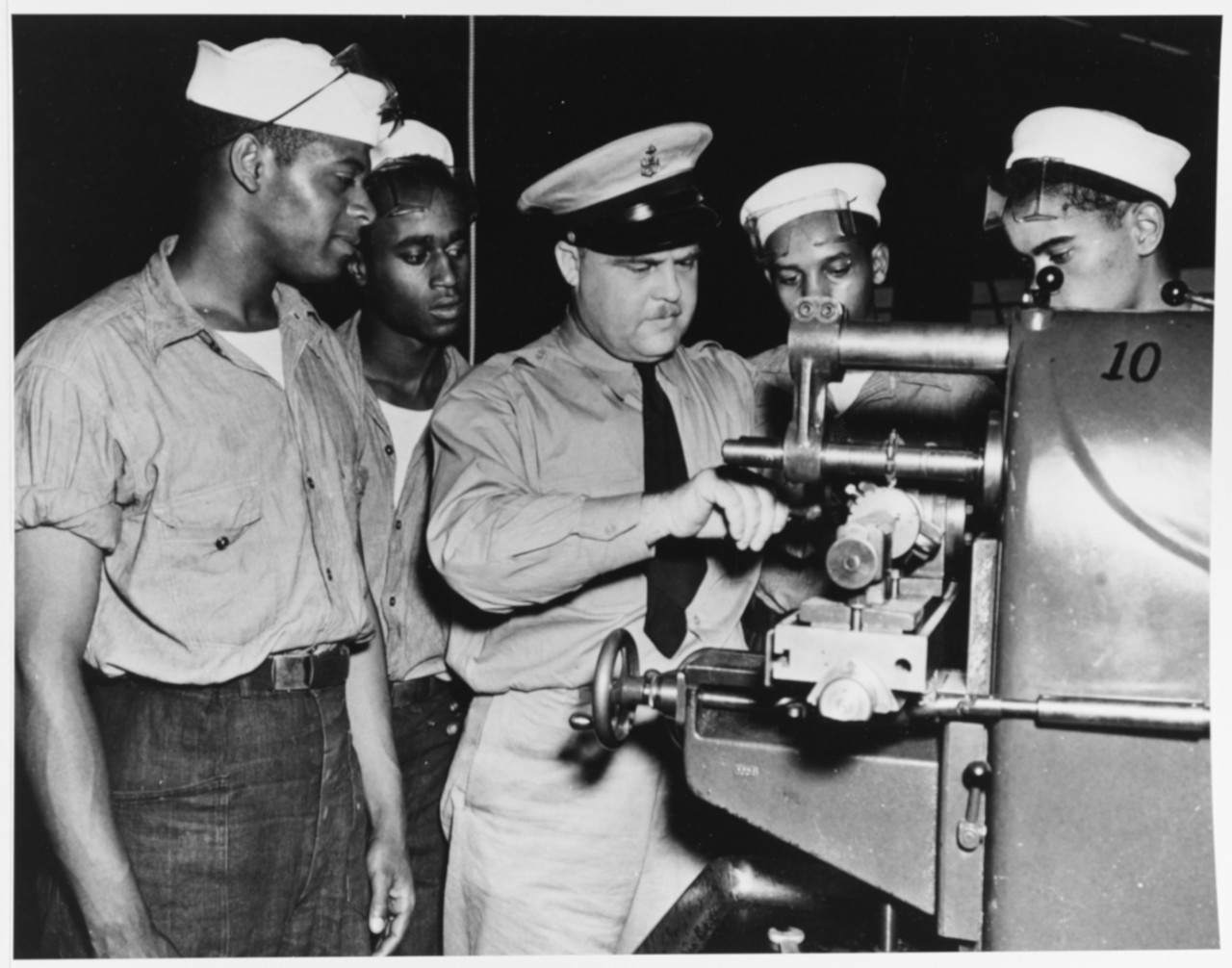

The first class of Black apprentice seamen at a segregated service school for machinist’s mates receives instruction from a White chief petty officer. The photo is dated 30 July 1943. (NHHC, 80-G-294865)

Although the U.S. Navy allowed Black sailors to be considered for ratings other than mess attendants as of 1 June 1942, the selection for advanced training was competitive. In the first class of 277, only 102 were selected for advanced training.[16] In addition to the limitations placed on the number of Black recruits selected for advanced training, Black mess attendants were not permitted to transfer to other ratings.[17] As of 1 February 1943, more than two thirds of Black sailors serving in the U.S. Navy were mess attendants.[18] That same month, the messman branch was changed to the steward branch. The change in the name did not change the stigma of servitude attached to this rating among Black recruits. The Navy could not afford to deplete the steward’s branch by allowing too many transfers or allowing too many recruits to be selected for training in other ratings.

Aware of the high percentage of illiteracy within their ranks and its potential effect on selection to advanced training schools, those recruits at Camp Robert Smalls who were educated sought to establish a school, termed the “remedial school,” within the training camp.[19] They stood up the unofficial program beginning in the fall of 1942.[20] Those who had an education before enlisting in the Navy volunteered to teach others the basics: reading, writing, and arithmetic.[21]

In December 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9279, forcing all services to utilize the Selective Service system for recruitment. The Navy was therefore required to take its share of the Black draftees into its service. Segregation within the Navy established a policy that denied opportunities based on skin color. Therefore, segregation bred resentment within the ranks of Black sailors. This tension culminated in incidents such as a riot at Naval Ammunition Depot at St. Julien’s Creek, Virginia, in June 1943, and a protest on a Naval Construction Battalion transport in the Caribbean in July 1943.[22] The influx of Black draftees forced the Navy to reassess its training programs and its policies toward segregation.

Company 833, made up of all Black recruits, in formation on 20 August 1943 at Naval Training Station Great Lakes, Illinois. (NARA, 520605)

The Navy established a special programs unit to assess solutions to racial tensions resulting from the policy of segregation. In August 1943, the Navy made the “remedial school” into an official program at Camp Robert Smalls and other naval training facilities.[23] The Navy also expanded its curriculum to include refresher courses for those entering service schools.[24] Incoming recruits who were classified as illiterate were enrolled in a course to provide the students with the equivalent of a fifth-grade education.[25] This program continued to expand, increasing the number of students and teachers, to a point at which nearly 23 percent of incoming recruits were required to attend the school as of August 1944.[26] The Navy acknowledged this school as “an asset to the service.”[27]

Adlai Stevenson, the special assistant to the Secretary of the Navy, was among those who encouraged Knox to create a class of Black sailors to commission as naval officers in 1943. The first 16 Black officer candidates arrived at Camp Robert Smalls in January 1944. In March 1944, the first 12 of these men were commissioned as ensigns. Another one became a warrant officer. The group later chose the nickname “Golden Thirteen” at a reunion. At the time of their commissioning, these officers did not receive a graduation ceremony or fanfare. They were assigned to command shore logistics operations, small vessels, and training units for Black recruits. For example, Ensign Dennis D. Nelson, II, a graduate of Fisk and Howard Universities, was put in charge of the new remedial learning program at Great Lakes.[28]

Following the death of Frank Knox in April 1944, James Forrestal was selected as the new Secretary of the Navy. He accelerated the conversion from segregation to integration in the Navy, encouraging further integration of Black sailors into seagoing operations. He guided the Navy through the final stages of integration and the end of the war.

In June 1945, the Bureau of Naval Personnel ordered the integration of the training of new recruits. Camp Robert Smalls remained open, but trainees were assigned regardless of race to the same companies, barracks, and mess halls. The inefficiency of segregated service schools quickly resulted in their subsequent integration. Camp Robert Smalls closed with the official desegregation of the armed forces on 26 July 1948 by Executive Order 9981.[29] After the closing of the segregated training facilities, the camp's name reverted to Camp Barry.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

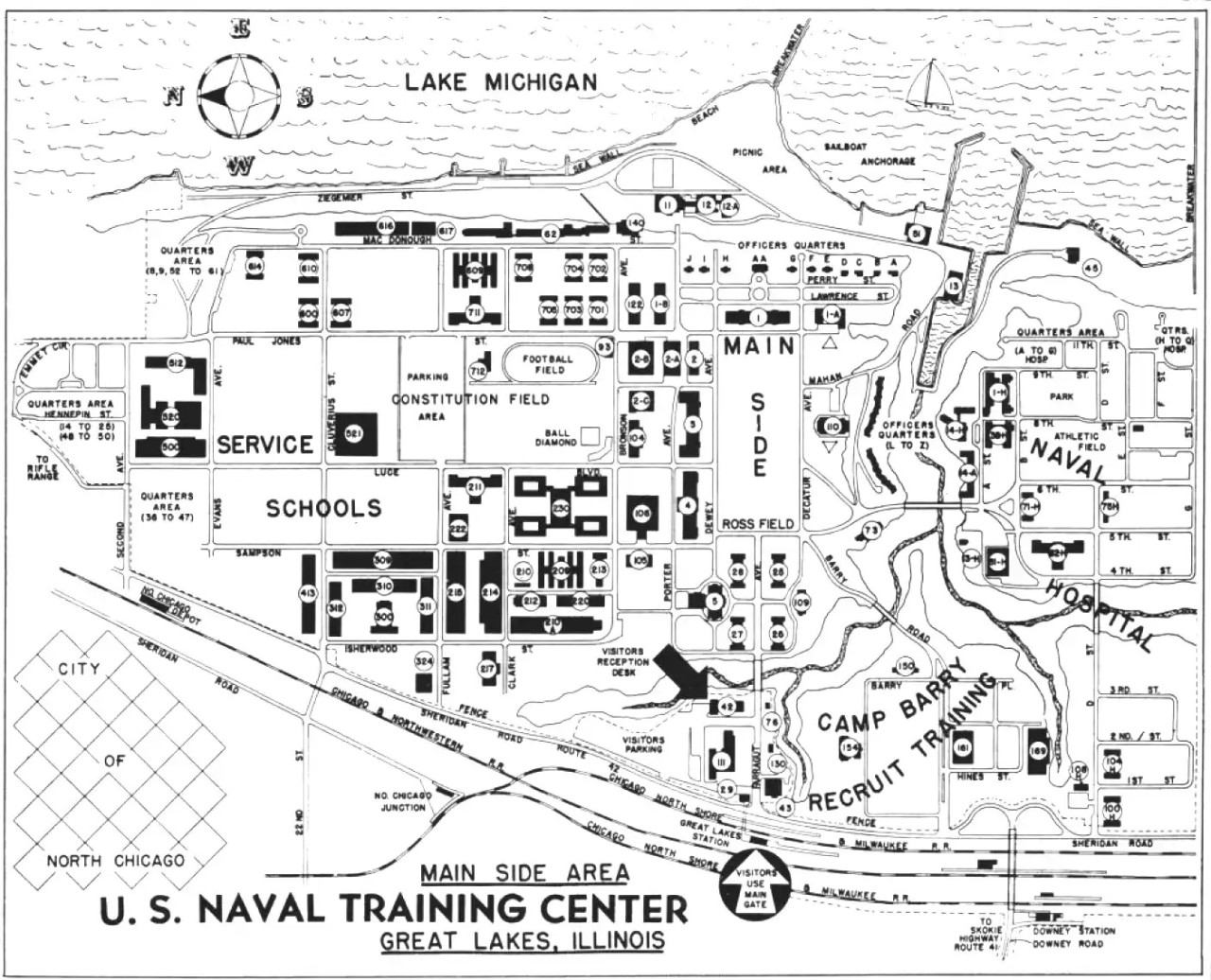

Map of the main side area of Naval Training Center Great Lakes, c. 1959. (All Hands, September 1959, pg. 19)

NHHC Resources:

African Americans in the Navy after World War II Through the Korean War

African Americans and the Navy: World War II Activities at Great Lakes Naval Training Station

An Equal Chance in the Battle of Life: The Navy’s Camp Robert Smalls, National Museum of the American Sailor

Hampton Institute and the Navy during the Second World War, Part II: The Compromise, Hampton Roads Naval Museum

H-Gram 78/H-0078-2: Ship Renaming, by NHHC Director Samuel Cox

Further Reading:

Bureau of Naval Personnel. The Negro in the Navy, vol. 84 of Administrative History of World War II. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1947.

Bureau of Naval Personnel, "Guide to Command of Negro Naval Personnel," NAVPERS-15092, 12 February 1945.

Dixon, Chris. African Americans and the Pacific War, 1941–1945: Race, Nationality, and the Fight for Freedom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Kelly, Mary Pat. Proudly We Served: The Men of the USS Mason. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1995.

Nalty, Bernard C. Long Passage to Korea: Black Sailors and the Integration of the U.S. Navy. Washington DC: Naval Historical Center, 2003.

***

NOTES

[1] To read more about the timeline of events leading to this decision, see Regina T. Akers, “African Americans in General Service, 1942,” Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), 23 March 2017. Note that the Bureau of Navigation was renamed the Bureau of Naval Personnel in May 1942.

[2] “The Navy: Where Do We Stand?” Pittsburgh Courier, 18 April 1942.

[3] Bureau of Yards and Docks, Building the Navy’s Bases in World War II: History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps, 1940–1946 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1947), 266.

[4] MacGregor, Integration of the Armed Forces, 67.

[5] “Plans for Escape,” Hagley Museum, accessed 29 January 2024.

[6] Morris J. MacGregor, Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940–1965 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army, Center of Military History, 1981), 67.

[7] “Army & Navy: Black Sailors,” Time, 17 August 1942.

[8] Morris J. Soublet, interview by Tracey E. Panek, Port Chicago Naval Magazine Oral History Project, National Park Service, 10 April 1999, p. 2, in Robert L. Allen Papers, University of California–Berkeley, Berkeley, CA.

[9] Samantha Belles, "An Equal Chance in the Battle of Life: The Navy’s Camp Robert Smalls," Sailor’s Attic (blog), National Museum of the American Sailor, NHHC, 17 February 2022.

[10] Dan C. Goldberg, The Golden Thirteen: How Black Men Won the Right to Wear Navy Gold (Boston, MA: Beacon Press), 98–99.

[11] Dennis D. Nelson, The Integration of the Negro into the United States Navy, 1776–1947 (New York: Farrar and Strauss, 1951), 96–98; also see MacGregor, Integration of the Armed Forces, 67.

[12] Bureau of Naval Personnel, "Guide to Command of Negro Naval Personnel," NAVPERS-15092, 12 February 1945.

[13] James V. Hatch, Sorrow Is the Only Faithful One: The Life of Owen Dodson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995), 95.

[14] Quoted in Mary Pat Kelly, Proudly We Serve: The Men of the USS Mason (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2015), 24.

[15] Sammie L. Boykin, interview by Tracey E. Panek, Port Chicago Naval Magazine Oral History Project, National Park Service, 14 August 1999, p. 3, in Robert L. Allen Papers, University of California–Berkeley, Berkeley, CA.

[16] Opportunity 23, no. 1 (Winter 1945): 36.

[17] This policy remained until June 1950 regardless of qualifications.

[18] Bureau of Naval Personnel, The Negro in the Navy, vol. 84 of Administrative History of World War II (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1947), 5.

[19] “‘Boots’ Can Get General Education,” Michigan Chronicle, 25 September 1942, 13.

[20] The Negro in the Navy, 60.

[21] Lyman Johnson, interview by John Egerton, 12 July 1990, Southern Oral History Program Collection, 12; Susan Hutton, “An Integrated Life,” University of Michigan, 26 February 2018.

[22] MacGregor, Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940–1965 (1981), 75.

[23] Joseph E. Hines and Samuel C. Howard, “College Resources and the Performance of Black Naval Officers,” master’s thesis (Naval Postgraduate School, 1991), 13

[24] “Remedial School Established at Camp Robert Smalls for Illiterate,” New York Age, 16 October 1943; “Great Lakes Remedial Unit Comes of Age,” 5 August 1944, Michigan Chronicle, 13.

[25] MacGregor, Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940–1965 (1981), 77.

[26] “Remedial School at Great Lakes Increases Enrollment from 200 to 1400,” New York Age, 12 August 1944.

[27] Bureau of Naval Personnel, "Guide to Command of Negro Naval Personnel."

[28] New York Age, 12 August 1944.

[29] Executive Order 9981, NHHC, 20 July 2023.