Seapower in Great Power Competition: Britain Wins the First Global War

Francis (Frank) Hoffman, Ph.D.

This essay is the third prize winner from the CNO Naval History Essay Contest in the Professional Historian category. The content of the original essay has been copyedited prior to publication.

In an era of dangerous great power competition, the stakes were high. The nation was extracting itself from a less than decisive war, and was deeply in debt. Its future economic prosperity was challenged. Its main rival was a continental power with the world’s largest economy, vast resources, and three times its population. Its adversary sponsored proxy forces and terrorists that attacked along the periphery of its partner’s frontier. The country’s political leadership was divided on which threat was the most important and how to respond. It could not do it all, but it had no coherent grand strategy for building up and using its armed forces to face its competitor.

This may sound like today’s situation, but it is actually drawn from one of history’s greatest strategic rivalries, Great Britain versus France, in the middle of the eighteenth century. Ironically, this case is not addressed by recent scholarship in strategic rivalries.[footnote:footnote0]

While historical analogies are never perfect, this one contains numerous continuities that are worth studying for their strategic application today. Like our “cousins” in England in the 1750s, we are engaged in combat in several theaters. Our economy is growing, but is not sustainable due to rising debt. Our executive branch and Congress remain divided and at loggerheads, just as they were in Great Britain. Over 15 years of counterinsurgency and six years of budget sequestration have left the armed forces short on readiness and modernization. Not surprisingly, military leaders and the U.S. defense strategy cite an eroding competitive edge.[footnote:footnote1]

Meanwhile, China has emerged as a major driving force in both economic and political clout, and has embarked on building up its naval force for blue-water operations, with an array of capital ships, long-range missile systems, and more sophisticated technology. Our Navy is too small to fulfill all its missions and train appropriately for its assigned tasks.

Competitive Strategy

Great Britain’s strategy in the Seven Years’ War is quite appropriate for detailed study.[footnote:footnote2] Strategy is a hard thing to get right, and many factors constrain the attainment of ambitious goals. As Freedman stated, “It’s about getting more out of a situation than the starting balance of power would suggest. It’s the art of creating power.”[footnote:footnote3] No one proportioned aspirations to the constraints of his day better than William Pitt when he was prime minister. The ability to constantly balance one’s aims and resources is the key to strategy.[footnote:footnote4] Pitt was the rarest of combinations — a brilliant strategist, with an eye for talent, and an aggressive politician.[footnote:footnote5]

There were five elements of Pitt’s strategy, or what he called a “system”:

1. North America was the selected main theater of effort with a strategic offensive aimed at eliminating French influence in New Canada.

2. Large subsidies were granted to Prussia to sustain its army and protect Hanover and keep the French occupied on the continent.

3. French Atlantic ports were blockaded by the Royal Navy as a strategic defensive to keep the French fleet from having freedom of action.

4. Amphibious raids were used to keep the French army tied down, to pull resources away that would potentially be used against London’s ally, Prussia.

5. Other colonial possessions in the Caribbean and West Indies were targeted for seizure to weaken French economic interests.[footnote:footnote6]

Like the defense strategy issued by Secretary of Defense James Mattis in January, Pitt outlined critical lines of effort: military, organizational, and diplomacy, with an expanded constellation of allies. Prioritizing these elements, stressing Great Britain’s strengths, and applying them against the identified vulnerabilities of his adversary was the central guiding logic of London’s strategy.

Applied Strategy

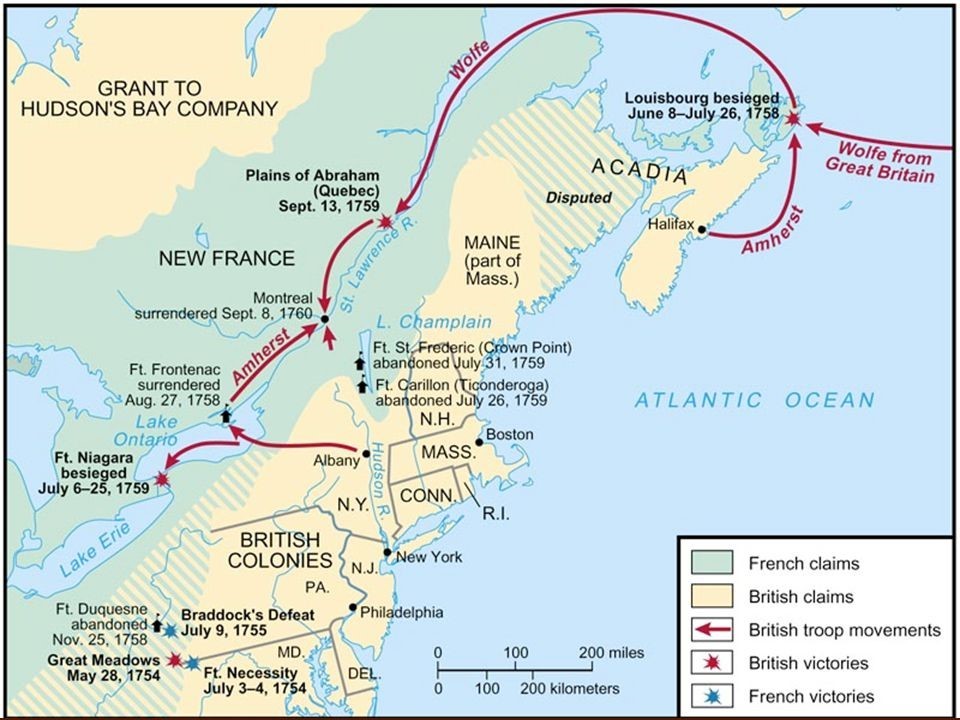

Pitt’s approach was not immediately effective. In 1757, London continued to face losses in both North America and elsewhere. The most embarrassing example was the Royal Navy’s failure to prevent the French navy from reinforcing Louisbourg in Nova Scotia. Poor communications and weather wasted an entire campaign season.

In 1759, with Pitt’s clear instructions and more aggressive commanders, the tide turned in Britain’s favor. France hoped to hold the port and citadel of Louisbourg by means of naval reinforcements. But the British blockaded the French fleet sailing from Toulon, and at the naval battle of Lagos in August, Vice Admiral Edward Boscawen defeated a French fleet led by the Marquis de la Clue. The French lost five ships in an otherwise indecisive battle.[footnote:footnote7]

Strategically, Lagos was important, since it left the French with a fleet of only 11 ships in Louisbourg to oppose the British. There, the French commander, Augustin de Drucour, had 3,500 regulars and approximately 3,500 marines and sailors to defend against a force twice their size. Meanwhile, British forces were assembled at Halifax, where army and navy units spent a month training. The fleet, under the command of Admiral Edward Boscawen, consisted of 150 transport ships and 40 men-of-war. The amphibious force included almost 14,000 soldiers, mostly regulars, led by Major General Jeffrey Amherst and Brigadier General James Wolfe.

On June 2, the British force anchored some three miles away. Bad weather prevented an immediate landing and siege. At daybreak on 8 June, Wolfe led a landing force ashore at Freshwater Cove. French defenses were initially successful, and after heavy losses, Wolfe planned to retreat. However, at the last minute, his light infantry found a protected inlet and Wolfe secured a beach head. Outflanked, the French withdrew into the fortress city. The British slowly built up an artillery battery of 70 cannon and mortars ashore, including naval guns, to support the reduction of the city’s fortifications. On 19 June, the British batteries were in position and opened fire. The long siege had begun. Chance plays a role in all wars, and this campaign was no different. A lucky round from a British mortar hit the 64-gun French Le Célèbre on July 21, starting a raging fire that carried over to two other ships, L’Entreprenant and Le Capricieux. The loss of powerful, 74-gun L’Entreprenant was a huge loss. Two days later, a British “hot shot” hit and destroyed the fortress’s headquarters, known as the King’s Bastion. Then Admiral Boscawen sent in a cutting- out party to attack the remaining French ships. Under the cover of fog, Bienfaisant was captured and Prudent burnt, eliminating resistance in the harbor. The French formally surrendered the next day, depriving New France of any major naval base and opening the Saint Lawrence River to penetrating attack.

Quebec. British operations in North America picked up their momentum as well. Army forces seized Niagara, Ticonderoga, and Crown Point in 1759, which gave the British control over the Great Lakes. These were designed to create an opening into the St. Lawrence River area and France’s major outposts at Quebec and Montreal. Under the command of Vice Admiral Charles Saunders, some 22 ships of the line, 13 frigates and 55 support vessels carefully navigated the treacherous waters of the St. Lawrence to bring Wolfe’s force into position below the Plains of Abraham to attack Québec.[footnote:footnote8] Wolfe got seven battalions of infantry up a small path in the night, as well as a pair of six-pounders hauled up by sailors. Saunders’s improvised gunboats provided mobility, fire support, and essential supplies for Wolfe’s daring assault.[footnote:footnote9]

- [footnote:footnote0]Three otherwise astute histories of strategic cases overlook it, including Williamson Murray, McGregor Knox, and Alvin Bernstein, eds., The Making of Strategy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001); James C. Lacey, ed., Great Strategic Rivalries: From the Classical World to the Cold War (New York, Oxford University Press, 2016); and Williamson Murray and Richard Hart Sinnreich, eds., Successful Strategies: Triumphing in War and Peace from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2014). Only Harvard’s Graham Allison includes an extended Anglo-French case from the seventeenth to mid-eighteenth century in his Destined for War, Can American and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap? (New York: Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt, 2017).

- [footnote:footnote1]James N. Mattis, Sharpening the U.S. Military’s Competitive Edge: A Summary of the National Defense Strategy of the United States (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, Jan. 2019).

- [footnote:footnote2]Richard Neustadt and Ernest May, Thinking in Time: The Uses of History for Decision-Makers (New York: Free Press, 1988).

- [footnote:footnote3]Lawrence Freedman, Strategy: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), xii.

- [footnote:footnote4]John Lewis Gaddis, On Grand Strategy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 98–99.

- [footnote:footnote5]Williamson Murray, “Grand strategy, alliances and the Anglo-American way of war,” in Grand Strategy and Military Alliances, eds. Peter R. Mansoor and Williamson Murray (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 28–29. For more historical insights on his life and times, see Jeremy Black, Pitt the Elder (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

- [footnote:footnote6]Adapted from Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783 (New York: Dover, 1987), 296.

- [footnote:footnote7]Sam Willis, “The Battle of Lagos, 1759,” The Journal of Military History, Vol. 73, No. 3 (July 2009): 745–765.

- [footnote:footnote8]Romanticized by Francis Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe (New York: Modern Library, 1999). See also Anderson, Crucible of War, 344–388.

- [footnote:footnote9]On improvised fire support, see John B. Hattendorf, “The Struggle with France, 1689–1815,” in The Oxford Illustrated History of the Royal Navy, ed. J. R. Hill (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 99.

Figure 1. Major British Campaigns in North America in Seven Years’ War

In the morning, Wolfe arrayed his forces in a linear line, in a poor position to receive an attack. Montcalm could have calmly awaited the British behind entrenchments, but elected to give battle. Somewhat ironically, an irregular war in North America was won in the most traditional method, with two lines standing across from each other firing muskets.[footnote:footnote10]Yet, it was a classic combined operation, as one historian stressed, “It would be impossible to exaggerate the importance of the part played by the British navy in that operation.”[footnote:footnote11]

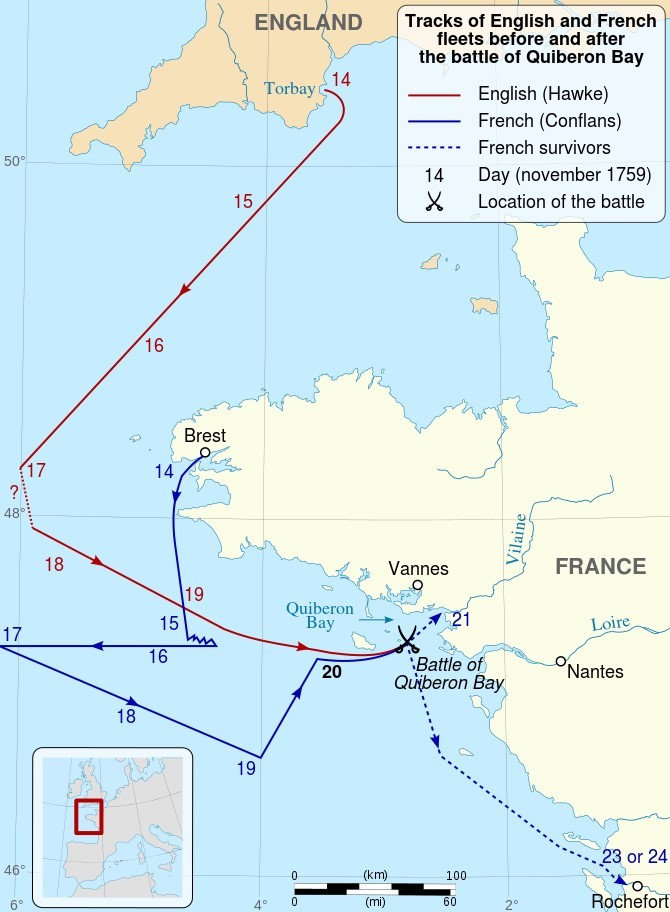

Quiberon Bay. France realized it was losing the conflict, and it decided to strike directly at Great Britain. It began amassing troops and transports in coastal ports for the invasion force. Spies kept the Admiralty informed, and the Royal Navy kept the French fleet under close blockade. Paris ordered the Marquis de Conflans to sail from Brest and escort the amphibious force to Scotland. At the English port of Torbay, after months of an arduous blockade, Sir Edward Hawke was ordered to intercept Conflans. He caught the French fleet on November 20 outside of Quiberon Bay.

Like Nelson over 45 years later, Hawke had supreme confidence in his captains and their well-trained crews. He elected to follow the French into the dangerous shoals inside the bay to get at Conflans’s force. Instead of slavish obedience to the rigid Royal Navy’s Fighting Instructions, Hawke unleashed his subordinates.[footnote:footnote12] The resulting melee destroyed and scattered the French. Conflans lost seven ships and the rest were bottled up.[footnote:footnote13] More importantly, the French navy was eliminated as an effective fighting force and its ability to threaten England was dashed. With the cream of French naval power beached or burning, the British were able to expand their missions globally against France. Mahan called it “the Trafalgar of this war.”[footnote:footnote14] In some respects, it was more strategically important than Nelson’s iconic victory since it negated an invasion.[footnote:footnote15]

- [footnote:footnote10]Walter R. Borneman, The French and Indian War: Deciding the Fate of North America (New York: Harper Collins, 2006), 221.

- [footnote:footnote10]Walter R. Borneman, The French and Indian War: Deciding the Fate of North America (New York: Harper Collins, 2006), 221.

- [footnote:footnote11]Guy Fregault, quoted in Daniel Baugh, The Global Seven Years War, 1754–1763 (Harlow, UK: Pearson, 2011), 420.

- [footnote:footnote12]Fred Anderson, Crucible of War, The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766 (New York: Vintage, 2001), 381.

- [footnote:footnote13]Andrew J. Graff, “Chaos Under Control: Lessons from Quiberon Bay,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 2 (February 2018): 40; Anderson, Crucible of War, 377–383.

- [footnote:footnote14]Mahan, Sea Power, 304.

- [footnote:footnote15]Brian James, “The Battle that Gave Birth to an Empire,” History Today (December 2009): 26–32.

Figure 2: English and French Fleet Tracks at Quiberon Bay

Montreal. The British army continued its campaign in Canada the next year with the navy holding Louisbourg and the St. Lawrence, blocking French reinforcements or supplies. Over 18,000 men maneuvered into Canada to take Montreal along three waterways: Brigadier James Murray’s small army of 3,800 men moved down along the St. Lawrence from Québec; another 3,400 soldiers under the command of Brigadier William Haviland arrived via the Richelieu River, and the final contingent moved on the St. Lawrence from Lake Ontario with Major General Jeffrey Amherst at the head of 11,000 men. This three-way pincer made Montreal indefensible; on September 8, 1760, it was surrendered. Amherst’s victory removed the French presence in North America.

Great Britain gained its strategic objectives with a combination of means that expanded the character of the competition. The British out-partnered, out-innovated, out-maneuvered, and when necessary, out-fought the French. If the essence of strategy is creating more power out of a situation than the initial conditions suggest, then Pitt was a master.[footnote:footnote16] The year 1759 was the year that historians date as the time Great Britain became the globe’s powerful nation.[footnote:footnote17]

However, the war went on for several years with British victories in the West Indies and India setting up Great Britain’s status as a global power for the next century.

Why was Great Britain Successful?

At the end of the period of Pitt’s tenure, Great Britain was the established great power. True, the seeds for American independence were set, and London was in debt. But Britain’s imperial reach and power were set for the next century. It is instructive to understand why this strategy was effective, and this section underscores some key elements.

Diagnosis of the Environment. In crafting his strategy, Pitt understood the need to conduct a thorough diagnosis of the strategic environment per Rumelt’s guidance on good strategy.[footnote:footnote18] Much about North America and its politics, geography, and economic potential was new to him, and Pitt ensured he mastered the subject. His years as the treasurer for the armed services permitted that he was intimately familiar with the size, structure, locations, and costs of military operations. His intelligence network helped him stay apprised of France’s capabilities too. This intellectual capital and “net assessment” are the cognitive foundation of any sound strategy.

Synergistic Competitive Strategy. The British government’s strategic approach was a classical competitive strategy.[footnote:footnote19] Most competitive strategies operate over long periods of time, usually in peacetime, using approaches that pit national security enterprises (including intelligence, information operations, acquisition, research laboratories, etc.) against each other at the institutional level. The most important matter is to discern domains (sea, air, or land) or functions in which one can gain and sustain a comparative advantage. The cardinal rule is to pit strength against weakness over time to gain and hold that advantage.

There was a symbiotic relationship between Britain’s government, her finances, her foreign policy, and the sustainment of its navy.[footnote:footnote20] The goal of this competitive strategy was to apply sustainable strengths against identified enduring weaknesses in the opponent. Thus, the British exploited their vast maritime power, and sought to avoid contesting France in conventional ground combat in Europe.

Pitt sought to generate dilemmas. France could project its army to expand or defend its borders, or defend her coastal towns and significant commerce overseas, or she could defend her colonial possessions in the New World or India with their potentially valuable income revenues. It could not do all of these, however. As the National Defense Strategy explicitly seeks to generate dynamic and unpredictable employment options and create dilemmas for future foes, we would do well to examine Pitt’s expanded and competitive conception of strategy.

Competitive Diplomacy. Pitt also understood the need to compete in the political dimension of strategy. He consciously sought to bolster the strength and number of allies he could count upon to help advance England’s interests in Europe. For maritime powers, alliances have historically proven to be an essential aspect of grand strategy.[footnote:footnote21] This is little reason to think that the future will not reinforce that strategic reality.

The payment of quite substantial subsidies to Prussia ensured that France could not devote extra attention to its maritime capabilities. To weaken France even more, Pitt tried to peel off partners from France, particularly Spain. Finally, the dramatic shift in how London treated the colonies was significant. Pitt promised the colonial state assemblies that Great Britain would pay for the raising and equipping of levies of troops. This ensured that New France faced a substantial force that didn’t overly tax England’s small army. They also made colonial officers equal to their equivalent grades in the British army. As a result, the colonies managed to substantially increase their troop contributions. If, as the National Defense Strategy contends, we seek a stronger constellation of allies and partners, Great Britain’s example offers insights into the need to listen to coalition partners.

Prioritization. Grand strategy—strategic historians advise—is all about balancing risk and keeping aims, resources, and interests aligned.[footnote:footnote22] Prioritizing strategic effort is the essential task of the strategic leader.[footnote:footnote23] Pitt was maniacal about priorities and strategic alignment, despite the uncertainties he faced. He was clear on his priorities about theaters, in terms of seeking decisive results first in North America, containing France on the continent, and then the West Indies. [footnote:footnote24]While Europe was not the priority, it was not ignored in terms of naval or army forces, yet it was the defensive theater. Pitt sought to weaken France in the other theaters with a strategic offensive of Britain’s time and choosing.

His selection of which domain to focus on was equally clear. Pitt was a member of the blue-water school in British circles. He deliberately exploited the strong “wooden walls” of the Royal Navy to block France’s ability to operate in the Atlantic and the English Channel. This leveraged Britain’s substantial maritime assets. In terms of total ships of the line, merchant fleet, shipyards and naval stores, Britain operated from a clear measure of superiority.[footnote:footnote25] Great Britain started with 130 ships of the line, while the French could claim less than half that number, only 63 hulls were in commission and many lacked adequate armament.[footnote:footnote26] At the end of the war, the Royal Navy had expanded by 30 ships, while France’s fleet was a dozen ships of war smaller.

Multi-Domain or Combined Operations. In addition to classic blockading, the British exploited their naval prowess with amphibious descents. Frederick requested that the British execute these operations to keep the French distracted and dispersed.[footnote:footnote27] Mahan felt “these operations, which had but little visible effect upon the general course of the war.”[footnote:footnote28] Yet, they served a strategic effect of tying up thousands of French forces. It has been estimated that British raids on coastal towns along the French coast tied up 134 infantry battalions and more than 50 cavalry squadrons—forces that might have been applied against Prussia. Of course, amphibious landings were not unknown to the Royal Navy.[footnote:footnote29] However, naval and army cooperation were sometimes lacking, until pushed for by London.[footnote:footnote30] These operations had more than a symbolic purpose, they expanded the competitive space that France had to worry about.[footnote:footnote31] They were a form of dynamic force employment that would not be decisive by themselves but which generated dilemmas for France.

Modernization and Reform. Another line of effort was military reform. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Admiral George Anson, built up the naval yards, drove out corrupt contractors, enhanced medical care, expanded the navy from 55,000 to 85,000 sailors, and streamlined fleet and ship designs. He also organized at-sea replenishment to support the blockade system while also improving quality of life and food (and beer) aboard the fleets.[footnote:footnote32] He added 30 marine companies to support amphibious operations. By 1762 it is evident that Anson, the great organizer in the Admiralty, should get the lion’s share of the credit for the Royal Navy’s sustained efforts over four oceans. Pitt recognized this and praised the admiral to the House of Lords upon his death, “To his wisdom, to his experience and care the nation owes it glorious successes of the last war.”[footnote:footnote33]

History and Seapower

This all too brief history should generate serious thinking among American strategists. Recent scholarship overlooks this significant period despite its status as the first global war.[footnote:footnote34] Yet, it did not escape the attention of classical historians like Mahan or Corbett. If the nation needs to understand, in compelling terms, the merits of a maritime systemic strategic approach, this case study is useful.[footnote:footnote35] As Mahan noted, “At the end of seven years, the kingdom of Great Britain had become the British Empire.”[footnote:footnote36] We do not seek an imperium today but the strategic approach used in this major global competition warrants study.

Seapower was central to Britain’s strategic position, and London understood clearly that the country’s success required a calibrated admixture of strategy, finance, naval power, and commerce. More than any other factor, fiscal credibility and economic prowess gave Great Britain the capacity to execute and sustain its strategy.[footnote:footnote37] This was a comprehensive strategy that played to Great Britain’s strengths and targeted gaps in its competitor.

Britain’s sea-based economy, global reach, and maritime empire were firmly established during the Seven Years’ War.[footnote:footnote38] The Royal Navy was crucial to the political, economic, and military elements of Pitt’s strategy. Britain’s success was predicated upon the utility, mobility, and firepower of a lethal and well-supported fleet. France’s strategic dilemmas were the natural byproduct of London’s strategy and Britain’s Wooden Walls.

Mahan once observed that “Seapower does not appear directly in its effects upon the struggle.”[footnote:footnote39] While seapower may work best indirectly, in the Seven Years’ War, there were direct effects that were strategically decisive as they reduced France’s options and directly reduced her sources of economic and military power.

The importance of seapower will rise in salience in this century.[footnote:footnote40] It will be highly germane to the Indo-Pacific region. One does not have to embrace the Thucydides’ Trap argument to understand that the extant regional order is undergoing a severe test as China’s power grows.[footnote:footnote41] Robust forward-deployed maritime forces will be central to preventing that flashpoint from occurring, and responding promptly if called upon.[footnote:footnote42] This will require a fleet design with a sharper degree of prioritization rather than simply a large fleet.[footnote:footnote43] It will also require the supporting infrastructure which Anson leveraged to sustain his fleets far from home.

Conclusion

Anyone serious about geopolitics in the twenty-first century cannot escape the role of oceans. Anyone sincerely interested in geoeconomics cannot ignore the influence that seapower has on our lives and our welfare in a globalized world. Mahan must be blended with Mackinder, with a dash of Corbett too.[footnote:footnote44]

The exercise of sea control will change much from the eighteenth century, but the enduring value of seapower remains. Seapower’s strategic effect—in terms of controlling time, space, and economic activity on the oceans—remains invaluable, whether executed by a 74-gun, three-masted ship of the line, or a stealthy, nuclear-powered Virginia-class submarine.

Like Great Britain 160 years ago, our future will be determined by the “one sea.” As Admiral James Stavridis concluded, “we are an island nation, bounded by oceans and nurtured on the global commerce and strategic waterways of the world’s oceans. Without the oceans and our ability to sail them, we would be enormously diminished as a nation.”[footnote:footnote45] Great Britain’s leaders recognized this reality and acted upon it. To sharpen the U.S. military’s competitive edge, we must also act upon it. If not, we will find ourselves in a costly global war that will also enormously diminish our prosperity and security.

*****

Francis (Frank) Hoffman, Ph.D., is a distinguished research fellow at the National Defense University. He retired from the United States Marine Corps Reserve in the summer of 2001 at the grade of lieutenant colonel. He directed the NDU Press, which includes the journals Joint Force Quarterly and PRISM. From August of 2009 to June 2011, he served in the Department of the Navy as a senior executive as the Senior Director, Naval Capabilities and Readiness Department. Dr. Hoffman graduated from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania (B.S., Econ., 1978), and holds graduate degrees from George Mason University (M.Ed., 1992) and the Naval War College, (M.A., Security Studies, 1994). He earned his Ph.D. from the War Studies Department at King’s College, London.

Dr. Hoffman is the recipient of the OSD Award for Civilian Excellence (1995), the Department of the Navy Medal for Sustained Superior Civilian Service (1998), the Department of the Navy Superior Service Medal (2010), the Navy Commendation Medal w/ gold star, and the Navy Achievement Medal. His numerous writing awards include Author of the Year from the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings for 2016.

- [footnote:footnote16]For more on Sir Lawrence Freedman’s influential views on strategy, see Benedict Williamson and James Gow, eds., The Art of Creating Power: Freedman on Strategy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017).

- [footnote:footnote17]Frank McLynn, 1759: The Year Britain Became Master of the World (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2004).

- [footnote:footnote18]Richard Rumelt, Good Strategy, Bad Strategy, The Difference and Why It Matters (New York: Currency, 2011). See also F. G. Hoffman, “Crafting a ‘Good’ Strategy,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 138, no. 4 (April 2012).

- [footnote:footnote19]Thomas Mahnken, ed., Competitive Strategies for the 21st Century: Theory, History, and Practice (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012).

- [footnote:footnote20]N.A.M. Rodgers, The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649–1815 (New York: Norton, 2005).

- [footnote:footnote21]Williamson Murray, “Grand Strategy, Alliances and the Anglo-American Way of War,” in Grand Strategy and Military Alliances, eds., Mansoor and Murray. This point is reinforced by Lacey, Great Strategic Rivalries, 40–41.

- [footnote:footnote22]Williamson Murray, “Thoughts on Grand Strategy,” in The Shaping of Grand Strategy: Policy, Diplomacy, and War, eds. Williamson Murray, Richard Hart Sinnreich, and James Lacey (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 6–9.

- [footnote:footnote23]Richard H. Sinnreich, “Patterns of Grand Strategy,” in The Shaping of Grand Strategy: Policy, Diplomacy, and War, eds. Williamson Murray, Richard Hart Sinnreich, and James Lacey, (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011) 263.,

- [footnote:footnote24]Lewis Libby and Thomas Kellan, “Daring to Win, Crafting Strategy to Defeat a Continental Behemoth” (Washington, DC: Hudson Institute February 2018).

- [footnote:footnote25]Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (London: Ashfield, 1983), 99.

- [footnote:footnote26]Mahan, Sea Power, 291.

- [footnote:footnote27]Julian S. Corbett, England in the Seven Years’ War: A Study in Combined Strategy, Vol. 1 (London: Longmans, Green and Company, 1918), 148.

- [footnote:footnote28]Mahan, Sea Power, 296.

- [footnote:footnote29]See Jamel Ostwald, “Creating the British Way of War: English Strategy in the War of the Spanish Succession” in Successful Strategies: Triumphing in War and Peace from Antiquity to the Present, eds. Williamson Murray and Richard Hart Sinnreich.

- [footnote:footnote30]David Syrett, “The Methodology of British Amphibious Operations During the Seven Years and American Wars,” The Mariner's Mirror 58, no. 3, (2013): 269–280.

- [footnote:footnote31]Rogers, Command of the Ocean, 271.

- [footnote:footnote32]Rogers, Command of the Ocean, 281.

- [footnote:footnote33]Quoted in Arthur Herman, To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the World (New York: Harper, 2004), 292.

- [footnote:footnote34]William R. Nester, The First Global War, Britain, France, and the Fate of North America, 1756–1775 (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2000).

- [footnote:footnote35]Peter Haynes Toward a New Maritime Strategy, American Naval Thinking in the Post-Cold War Era (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2015), 251–252.

- [footnote:footnote36]Mahan, Sea Power, 291.

- [footnote:footnote37]See Williamson Murray and Mark Grimsley’s “Introduction,” in The Making of Strategy, eds. Murray, Knox, and Bernstein.

- [footnote:footnote38]Andrew Lambert, “The Pax Britannica and the Advent of Globalization,” in Maritime Strategy and Global Order: Markets, Resources and Security, eds. Daniel Moran and James A. Russell (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2016).

- [footnote:footnote39]Mahan, Sea Power, 295.

- [footnote:footnote40]Geoffrey Till, Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-first Century (Oxon, UK: Routledge, 3rd ed., 2013), 339.

- [footnote:footnote41]Made famous by Graham Allison in Destined for War, Op Cit.

- [footnote:footnote42]Seth Cropsey and Byran McGrath, Maritime Strategy in a New Era of Great Power Competition (Washington, DC: Hudson Institute, 2018).

- [footnote:footnote43]For a strategic design, see Bryan Clark, Peter Haynes, Jesse Sloman, Timothy Walton, Restoring American Seapower: A New Fleet Architecture for the United States Navy (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, February, 2017

- [footnote:footnote44]Robert D. Kaplan, The Return of Marco Polo’s World (New York: Random House, 2018), 40.

- [footnote:footnote45]James Stavridis, Sea Power: The History and Geopolitics of the World’s Oceans (New York: Penguin, 2017), 342.