Princeton IV (CV-23)

1943–1944

A borough in west central New Jersey, scene of the Battle of Princeton (2–3 January 1777) during the American Revolution, in which Gen. George Washington led the Continental Army to a minor victory against a British force led by Lt. Gen. Charles Mawhood, part of an army under the command of Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis. Princeton also marks the birthplace of Como. Robert F. Stockton (20 August 1795–7 October 1866), who advocated for a steam-powered and propeller-driven navy.

IV

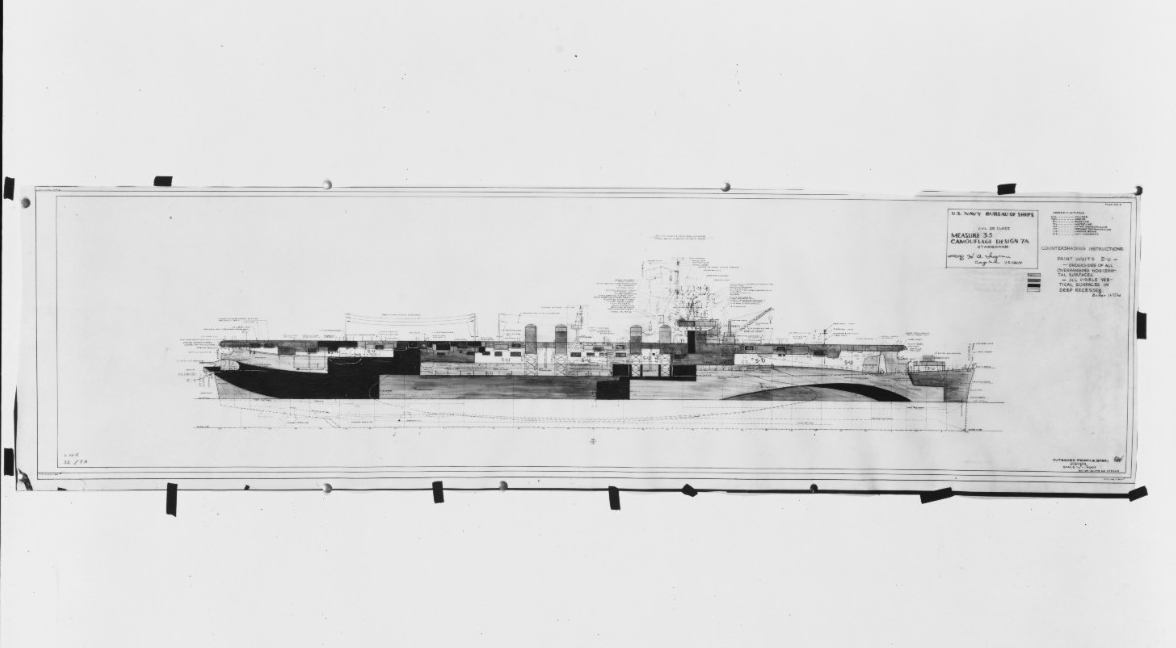

(CV-23: displacement 13,000; length 622'6"; beam 71'6"; extreme width 109'2"; draft 26'; speed 32 knots; complement 1,569; armament 22 40-millimeter, 16 20-millimeter; aircraft 45; class Independence)

Tallahassee (CL-61) was laid down on 2 June 1941 at Camden, N.J., by the New York Shipbuilding Corp.; with the fleet requiring additional aircraft carriers, however, the exigencies of the rapid expansion during World War II, and, in particular, the time required to build larger carriers, fueled the decision to convert some of the Cleveland-class ships as smaller carriers that could enter service sooner Tallahassee was therefore reclassified to an aircraft carrier (CV-23) on 16 February 1942; renamed Princeton on 31 March 1942; launched on 18 October 1942; sponsored by Mrs. Margaret S. Dodds (née Murray), wife of Princeton University’s President Harold W. Dodds; completed her preliminary acceptance trials on 22 February 1943; and was commissioned at Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pa., on 25 February 1943, Capt. George R. Henderson in command.

Leaks in Princeton’s gasoline tanks required additional alterations and complete retesting of the gasoline systems, and delayed her preliminary sea trials on 28 March 1943. Princeton trained during the succeeding weeks, and on 1 May, Fighting Squadron (VF) 23, Lt. Cmdr. Henry L. Miller of Fairbanks, Alaska, in command, accomplished carrier qualifications on board the ship. The squadron had been established at Naval Reserve Air Base (NRAB) Willow Grove, Pa., on 16 November 1942, and trained initially in North American SNJ Texans and Grumman F4F-4 Wildcats. One of the highlights of their training period occurred on 14 April 1943, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt inspected Carrier Air Group (CVG) 23, the squadron’s group and also led by Miller who served “double-hatted”, while they trained at Marine Corps Air Station Parris Island, S.C. Fighting Twenty-three boarded the carrier with a dozen Wildcats and a pair of Grumman F6F-3 Hellcats, the latter reinforcing the squadron so that all of the pilots could qualify in them. Composite Squadron (VC) 23, Lt. Cmdr. Martin T. Hatcher, comprised the group’s other squadron, which boarded the ship with nine Grumman TBF-1 Avengers and nine Douglas SBD-5 Dauntlesses.

Princeton wrapped-up the work and reported for duty on 18 May 1943. The ship then (28 May–3 July) set out for her shakedown cruise and carrier qualifications in the Gulf of Paria off Trinidad in the Caribbean. Each of VF-23’s pilots made a minimum of 30 landings in both types of fighters, including two night deck landings in Hellcats. One or more of the arresting wires broke as an F4F-4 Wildcat (BuNo 12039), flown by Lt. Cmdr. Miller, slammed into the barrier while landing on 20 May, damaging it beyond repair. The ship subsequently transferred the Wildcat to Carrier Aircraft Service Unit 21.

At one point three Wildcats, flown by Ensigns Jack M. Abell, William G. Buckelew of Beaufort, S.C, and Robert S. Tyner, all USNR, ran into heavy weather while flying an intercept problem and lost radio contact with the ship. The trio headed for the nearest land, and eventually made a forced landing on an emergency field in Venezuela. The men overcame severe linguistic handicaps and managed to wire details of their predicament to Port of Spain, Trinidad. The following day Princeton launched Avengers with full bomb bay fuel tanks that enabled the Wildcats to refuel and return to the ship.

A Wildcat (BuNo 03411) flown by Ens. Abell landed on Princeton with a slight bounce on 4 June 1943. The arresting hook also bounced several times and failed to engage any of the wires until the last, causing the Wildcat to slam into the barrier. Investigators discovered that the arresting hook also contained very little fluid and exerted no pressure on the hook. The barrier badly scarred the propeller, and the barrier wire damaged the lower section of the nose cowling and broke the propeller brush engine, causing the engine to suddenly stop. Abell had completed 20 carrier landings.

The voyage did not pass without loss because a Wildcat (BuNo 02008) flown by Ens. Oscar A. Cantrell, USNR, failed to return from a routine training flight on Sunday 6 June. The division flew into some light clouds while climbing, and upon emerging out of the top of the clouds noticed that he was missing. The searchers failed to locate the Wildcat or Cantrell.

On the 13th of that month as well, Ens. Buckelew continued to experience his share of ill fortune when a Wildcat (BuNo 12219) he was flying approached for a night landing slightly to the right of Princeton’s flight deck. The landing signal officer gave him a “cut” signal, but the Wildcat did not land on the center in time. The tail hook struck something solid (undetermined in the inky darkness) on the side of the deck and the impact tore it loose, along with about four feet of the after fuselage. Buckelew maintained control of the plane and rolled up the deck into the barrier. The accident damaged the propeller and engine.

Buckelew had completed 38 carrier landings, however, Princeton recorded that “when approaching for night landing, pilots have a tendency to veer to starboard to permit sight contact of the signal officer, thereby causing an off center landing to starboard. It is the opinion of this board that extending the signal officer’s platform at least three feet to port would permit better visibility for the pilots, thereby causing landings to be effected in the center of the deck. This condition is aggravated by extreme darkness of the flight deck.” The ship also lost an SBD-4 (BuNo 10641) of VC-23 on 22 June. The air group completed 1,242 carrier landings during the cruise, and upon their return flew ashore to NRAB Willow Grove for rest and leave.

Shortly thereafter, on 15 July 1943, Princeton was reclassified to a small aircraft carrier (CVL-23). The ship then (21 July–9 August) embarked CVG-23, with VF-23 replacing its Wildcats with 12 F6F-3 Hellcats, and stood out to sea in company with Belleau Wood (CVL-24), with CVG-24 embarked, to fight the Japanese in the Pacific. The two carriers steamed down the east coast, Princeton launching Hellcats for combat air patrols (CAP), and crossed the Caribbean. The vessels reached the Panama Canal on 26 July, where they rendezvoused with Lexington (CV-16), with CVG-16 embarked. The three carriers passed through the canal and two days later turned their prows westward toward Hawaiian waters.

The Pacific Fleet dispatched a plan to the three ships on 7 August 1943, directing them to stage a simulated attack against Oahu to determine the defenders’ alertness. The staffs carefully planned their raid and an hour before dawn on the 9th, the trio of carriers launched their planes from a position about 100 miles out. The attackers swept in on aircraft installations on the island, and only then did U.S. Army Air Force fighters rise to intercept them. Following the raid, the group temporarily flew ashore to Naval Air Station (NAS) Barbers Point, while the ships put in to Pearl Harbor, T.H., and refueled and provisioned. VF-23 served under the Army’s interceptor command, and at least one division was on alert call every morning and generally scrambled. Between the alerts both of CVG-23’s squadrons trained in group exercises, gunnery, and navigation hops.

Princeton arrived at a time when Vice Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, Commander, Fifth Fleet, ordered a number of operations as part of the Allied drive toward the Japanese home islands. Independence (CVL-22) and Princeton therefore transported naval construction battalion men (Seabees) and those of the Seventh Air Force that occupied Nakufetau and Nanomea in the Ellice Islands [Tuvalu] (18–28 August 1943). The sailors and soldiers immediately began building airfields on the islands to support further battles, and Princeton returned to Pearl Harbor. That day (the 28th) as the ship returned to Hawaiian waters, she lost a TBF-1 Avenger (BuNo 05919) of VC-23.

Princeton sortied with Task Force (TF) 11 on the 25th and headed for Baker Island east of the Gilbert Islands [Kiribati]. The ship left her nine Dauntlesses ashore and embarked a dozen F6F-3s of VF-6 in their place, which temporarily raised the ship’s fighter strength to 33 pilots and 24 Hellcats. The task force intended to land the Army’s 804th Aviation Battalion to occupy the island and construct an airfield there, and Rear Adm. Willis A. Lee Jr., led the vessels from his flagship Hercules (AK-41), a cargo ship converted for the purpose. Rear Adm. Arthur W. Radford hoisted his flag in Princeton in command of the force’s Task Group (TG) 11.2, which also included Belleau Wood, and provided daytime air cover. Lockheed PV-1 Venturas from Canton Island flew night patrols over the ships, and a fighter-director team sailed in destroyer Trathen (DD-530). Ashland (LSD-1) also took part in the operation and pioneered the use of the dock landing ship.

While the transports and Ashland disembarked soldiers and disgorged their cargoes shoreward on 1 September 1943, Trathen directed two VF-6 Hellcats, piloted by Lt. (j.g.) Richards L. Loesch Jr., USNR, and Ens. Albert W. Nyquist, USNR, to a radar contact 32 miles away. The fighters discovered a snooping Kawanishi H8K2 Type 2 flying boat and made a high side run and splashed the Emily, which dived into the water and exploded upon impact. The Americans dispatched the Japanese plane so quickly that the enemy did not have time to send a radio report of the landings. Two days later, Trathen again vectored a pair of Fighting Six Hellcats, Lt. (j.g.) Thad T. Coleman Jr., USNR, and Ens. Edward J. Phillipe, USNR, 20 miles to another Emily, which they also splashed into the sea.

Fighting Twenty-three experienced its baptism of fire at about 1300 on 8 September 1943, when the Japanese persistently sent a third Emily to reconnoiter the task force. Two of the squadron’s Hellcats, Lt. Harold N. Funk, and Lt. (j.g.) Leslie H. Kerr Jr., USNR, were patrolling some distance from Baker Island when Trathen vectored them to the enemy. The fighters sighted the Emily and attacked, bracketing the flying boat from a range of 400–500 yards. The Japanese returned fire but the F6F-3s swept past and flew another run, shooting the plane forward of its cockpit, starting fires in the forward section of the fuselage. The enemy ceased fire as the flames engulfed the entire plane, and plummeted to the water and disintegrated upon impact. The squadron marked the battle as its first combat victory. During these interceptions the Hellcats also photographed the flying boats so that intelligence analysts could examine the planes. The ship lost a VF-23 Hellcat (BuNo 25808), however, flown by Ens. W.A. Davis, on the 11th.

Completing the mission on 14 September 1943, Princeton rendezvoused with TF 15, Rear Adm. Charles A. Pownall, for a series of raids against Tarawa, Makin, and Abemama in the Gilberts (18–19 September). Planners orchestrated the strikes in order to decrease Japanese pressure on the occupation of the Ellice Islands and to provide operational training. Princeton carried out a long day of flight operations on the 18th (0338–1815), and VF-23 logged 170 pilot hours that day alone.

A flight of ten VF-23 Hellcats and five Avengers from Princeton joined another seven TBF-1s of Torpedo Squadron (VT) 16 and SBD-5s of VC-24 from Lexington and Belleau Wood, respectively, as the strike group lifted off before dawn and flew 92 miles to Tarawa. Arriving over the atoll 35 minutes before sunrise, they faced considerable Japanese antiaircraft fire as they bombed and strafed vessels, flak positions, and parked aircraft. The attack sank Japanese motor torpedo boats Gyoraitei and Gyoraitei No. 3, left eight bombers, most likely Mitsubishi G4M1 Type 1 attack plane (Bettys), burning, and started fires in the barracks area. The attackers spotted four Bettys flying in the distance on a retiring course but did not intercept them and the enemy winged off. Two Hellcats of VF-6, flown by Lt. Howard W. Crews and Ens. L.W. Gordon, escorted a pair of VC-23 Avengers as the bombers strafed and set afire three Emilys moored in the lagoon.

Hellcats also provided an umbrella of protection over the task force. That afternoon at 1413, a division of four fighters, flown by Lt. (j.g.)’s John P. Altemus (of VF-6), Leon W. Haynes, USNR, Jack D. Madison, USNR, of Moultrie, Ga., and James W. Syme, USNR, of Albuquerque, N. Mex., were vectored toward a Betty. The Hellcats flew seven runs against the bomber, and after the third pass a fire broke out around the Betty’s starboard engine and flames enveloped the cockpit. When the bomber dropped to only 50 feet above the water, it exploded and crashed into the sea. All of the division’s aircraft took part in the battle, but Madison and Syme were credited with the victory. Three of Princeton’s F6F-3 Hellcats (BuNo 25926 and two others) failed to return to the ship that day. In addition, the Japanese shot down two TBF-1s: (BuNo 05916), flown by Lt. (j.g.) Charles M. Branesfield, USNR, over Tarawa, and a second (BuNo 06193), over Makin.

“Congratulations to all hands,” Pownall signaled Princeton’s air group later that night. “Your alertness to meet the enemy in any way he chooses to fight was one of the many highlights of the day. It was well done.”

Aircraft flew a total of seven strikes over both days, and those from Lexington snapped a set of low oblique photographs of the lagoon side of Betio in the Tarawa Atoll, which helped planners prepare for the landings. The Americans lost four planes altogether. The ships then came about and headed back to Pearl Harbor. On their return cruise they crossed the equator on 22 September 1943, and King Neptune and his Royal Court arrived to enliven the event. The Polywogs, those men who had not yet crossed the line, outnumbered the Shellbacks, those who had, many times over, and VF-23’s historian wryly observed that “hence considerable punishment was meted out on both sides”. The evening before the ship crossed the “Polywogs were duly served with subpoenas, listing individual offenses which had been committed during our sojourn aboard and notification was given of costumes which would be worn the following day. After an adequate performance had been given on the flight deck, culminated by all Polywogs running the gauntlet through a long double line of eagerly awaiting Shellbacks, Neptunus Rex accepted all new hands into his Royal Domain”. The day did not pass without tragedy, however, as the ship lost a VC-23 TBF-1 (BuNo 47441) flown by Lt. (j.g.) John R. Marsh, USNR.

The task force returned to Pearl Harbor and Princeton’s group flew ashore to NAS Pearl Harbor on Ford Island, where the 12 pilots from VF-6 returned to their parent squadron. The ship lost a VC-23 Avenger (BuNo 47578) during a training flight on 27 September. Princeton subsequently switched out her air group and doubled-up on the number of fighters. VF-23 numbered 24 F6F-3 Hellcats, while VC-27 moved its nine SBD-5 Dauntlesses ashore and returned to the fighting with only nine TBF-1 Avengers.

In mid-October 1943, Princeton sailed for Espíritu Santo in the New Hebrides [Vanuatu], where she joined TF 38, Rear Adm. Frederick C. Sherman, on the 20th. Saratoga (CV-3), with CVG-12, embarked, and Princeton sailed together in the Relief Carrier Group, TG 50.4, and took part in Operation Cartwheel, the Allied plan to advance toward Rabaul, on New Britain in the Bismarcks. The Japanese had overrun the islands and heavily fortified and garrisoned them, in particula, turning Rabaul and its environs into a veritable fortress. Cartwheel consisted of a number of phases including Operation Cherryblossom—landings by the Third Marine Division, Maj. Gen. Allen H. Turnage, USMC, of the I Marine Amphibious Corps, Lt. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift, USMC, at Cape Torokina near Empress Augusta Bay, Bougainville, on 1 November 1943. Rear Adm. Theodore S. Wilkinson led the III Amphibious Force that landed and supported the marines. Aircraft, Solomons, including the Thirteenth Air Force, naval, marine, and Royal New Zealand Air Force squadrons, hurled planes against enemy airfields, vessels, and troops across the region in the days preceding the landings. Fifth Air Force planes also flew strikes from their fields in Australia, primarily against targets around Rabaul.

The SBD 4 and 5s and TBF-1s of VC-38, Marine Scout Bombing Squadron (VMSB) 144, and Marine Torpedo Bomber Squadrons (VMTBs) 143, 232, and 233, covered by Vought F4U-1 Corsairs of VF-17 and Marine Fighting Squadrons (VMFs) 215 and 221, bombed and strafed the Japanese defenders five minutes before the marines landed. A CAP averaging 38 fighters rotated over the beaches and disrupted major Japanese aerial counterattacks. The cruisers and destroyers of TF 39, Rear Adm. Aaron S. Merrill, also shelled targets in the area, and later bombarded Japanese airfields on Shortland Island in the Solomons. The enemy returned fire and damaged Dyson (DD-572).

Rear Adm. Sherman directed the carriers to launch their planes against Japanese airfields and installations in the Northern Solomons at Buka, which lies across the Buka Strait from Bougainville, and against Bonis on the peninsula of the same name on Bougainville, on 1 November 1943. The admiral and his planners intended for the raids to diminish Japanese aerial resistance against the landings at Cape Torokina. The attackers took off before dawn, which resulted in considerable confusion and delays in effecting their rendezvous. The engine failed on an F6F-3 (BuNo 25814), flown by Ens. Robert S. Tyner, USNR, and the Hellcat crashed into the water, though Tyner was rescued and returned to the ship. In addition, another VF-23 Hellcat (BuNo 25930), flown by Lt. (j.g.) David H. Olin, USNR, crashed but a destroyer also picked up the pilot.

Two TBF-1s (BuNos 24071 and 24176) of VC-23, manned by Lt. (j.g.) Charles C. Dyer, USNR, ARM2c James E. Nutt Jr., and AOM2c Richard G. Reinertson, and Ens. Gordon W. Spear, USNR, ARM2c Raymond G. Marshall, and ARM2c David C. Miller, respectively, collided in mid-air. Both Avengers crashed, killing Dyer, Nutt, Reinertson, and Miller, but Spear and Marshall survived and were rescued.

Planes flying from Princeton bombed and strafed the airfield, antiaircraft guns, and ground installations at Bonis, some of the Hellcats boldly dropping to tree-top level, and attacked an enemy merchantman southeast of Sohano Island. A pair of Hellcats, flown by Lt. Cmdr. Miller and Lt. (j.g.) Joe M. Webb, USNR, made two strafing runs on another cargo ship, and four hours later other planes observed that the Japanese beached her. A fighter flown by Lt. (j.g.) Walter J. Kirschke, USNR, strafed a 200–250-foot long cargo ship, towing two barges. The Hellcat made four runs and the strafing started huge fires, the smoke rising nearly 2,000 feet. Three hours later another plane reported that both the ship and her barges continued to burn furiously. Aircraft sank Japanese auxiliary submarine chaser Cha 13 west of Shortland Island.

The ship launched another coordinated strike that afternoon, and the planes attacked antiaircraft guns near the airfield at Bonis, and strafed two medium cargo ships near Buka passage. The Dauntlesses and Avengers catered the runway and damaged several Bettys in revetments with 100- and 200-pound general purpose bombs.

The following day on the 2nd, Saratoga and Princeton sent two coordinated strikes against the enemy airfields. Aircraft from Princeton bombed and strafed antiaircraft positions at Bonis, cut down a number of Japanese soldiers, and set fire to barrels of aviation gasoline stored along the edges of the runway. Hellcats furthermore strafed a couple of cargo ships. The enemy fought back fiercely and their antiaircraft fire, largely from 13.2- and 20-millimeter guns. The second attack that afternoon produced VF-23’s first combat loss when the defenders shot down one of Princeton’s F6F-3s (BuNo 66021), piloted by Ens. Leonard C. Keener, USNR, as the Hellcat flew a strafing run, killing Keener. The pilot hailed from Visalia, Calif., and was temporarily assigned to the squadron from VF-12. Ground fire also holed three fighters.

Rear Adm. Ōmori Sentarō led a Japanese force of two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and six destroyers that attempted to counterattack the transports off Bougainville. Merrill took four light cruisers and eight destroyers and intercepted and turned back Ōmori during the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay on the night of 1 and 2 November 1943. Japanese 8-inch gunfire damaged Denver (CL-58); a torpedo sliced into Foote (DD-511); and enemy gunfire and a collision damaged Spence (DD-512) and Thatcher (DD-514). Charles Ausburne (DD-570), Claxton (DD-571), Dyson, Spence, and Stanly (DD-478) sank Japanese destroyer Hatsukaze, which also collided with heavy cruiser Myōkō; and U.S. gunfire sank light cruiser Sendai and damaged heavy cruisers Haguro and Myōkō. In addition, destroyers Samidare and Shiratsuyu collided during the night surface action. Enemy planes attacked the U.S. ships as they retired and damaged Montpelier (CL-57). Sherman followed suit and launched planes for a second (planned) strike on Buka.

The Japanese sought to prevent the Allies from establishing their air power on Bougainville, and concentrated a number of cruisers and destroyers of the Second Fleet, Rear Adm. Takagi Takeo, in Simpson Harbor at Rabaul. On only 14 hours’ notice, Sherman led Saratoga, Princeton, and their screen northward to attack the fleet, at one point taking advantage of foul weather to mask their approach. On the morning of 5 November 1943, the carriers launched their aircraft from a position about 220 miles south-southeast of Rabaul against the vessels in Simpson Harbor.

“As our planes approached,” VF-23’s historian reflected, “the harbor was protected by an umbrella of terrific anti-aircraft fire, the likes of which our boys had never experienced before, and hope never to see again. Japanese fighter planes swarmed the sky, Zekes [Mitsubishi A6M Type 0 carrier fighters], Tonys [Kawasaki Ki-61 Hiens], Hamps [A6M3-32s]—everything the enemy could get airborne.”

The SBD-5s of Bombing Squadron (VB) 12, and TBF-1s and TBF-1Cs of VT-12, flying from Saratoga, and TBF-1s of VC-23 from Princeton, lashed the Japanese ships and shore emplacements. An hour later on 5 November 1943, 27 Consolidated B-24 Liberators of the Fifth Air Force’s 43rd Bomb Group, escorted by 58 Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, roared over the harbor and pounded the wharf area. The joint raid surprised the Japanese with many of their ships refueling and unprepared to sortie and escape, and with most of their planes initially on the ground.

The Americans damaged five Japanese heavy cruisers. Three 500-pound bombs narrowly missed but damaged Atago, killing her captain and 21 crewmen. Chikuma suffered injury from several near misses. A bomb sliced into Maya above one of her engine rooms, severely damaging the cruiser and killing 70 men. A 500-pound bomb tore into Mogami, setting her ablaze, and the ship lost 19 sailors. Two 500-pounders damaged Takao and killed 23 of her company. In addition, a bomb splashed close aboard light cruiser Agano, damaging an antiaircraft gun and killing a gunner, the attackers struck another light cruiser Noshiro, and finally, lightly damaged three destroyers—Amagiri, Fujinami (which lost one man), and Wakatsuki.

F6F-3s of VF-12 from Saratoga and VF-23 from Princeton flew through withering antiaircraft fire to tangle with the enemy on 5 November 1943, and Hellcats from Fighting Twenty-three claimed to splash ten enemy aircraft.

One of VF-23’s Hellcats, flown by Lt. (j.g.) Stanley K. Crockett, USNR, escorted Cmdr. Henry H. Caldwell, who led Saratoga’s CVG-12 in an Avenger containing photographic equipment. Caldwell’s crew comprised ARMC Robert W. Morey and AOM2c Kenneth Bratton. The Hellcat almost failed to accomplish the mission, however, because it suffered mechanical difficulties that made it impossible to lock the wings. Maintainers pushed it over to the side of Princeton’s flight deck while the other planes launched. Crockett determinedly urged them to make every attempt to put the plane in flying condition, and even though both air groups lifted off, rendezvoused, and turned onto their attack heading as planned, he insisted on launching as soon as the crewmen secured the wings. The fighter pilot raced to catch-up to the strike group and overtook them about 20 miles from the carriers, and maneuvered into position slightly above Caldwell’s torpedo plane and a second Hellcat from VF-12, Ens. Roberts. When the trio reached a point about five miles from Rabaul, they took a corresponding position on the other side of the group, and bore in over the mouth of Simpson Harbor at an altitude varying between 13,000–14,000 feet.

The Avenger began snapping photos while Japanese antiaircraft guns on board ships and emplaced around the harbor opened a thunderous barrage, and fighters began to rise to intercept the Americans. The Hellcats doggedly wove back-and-forth around the Avenger to protect the photographic plane while enemy fighters circled in the vicinity. Caldwell assigned targets to the group and ordered them to attack, and the three planes then turned north and skirted the northern shore of Crater [Gazelle] Peninsula. Together the Avenger and the pair of Hellcats reached Talili Bay, where they turned east to make a daring photographic run across the harbor down to 3,500 feet, flying directly into the flak thrown up by the warships and batteries ashore.

The planes emerged from the barrage over Ropopo Airfield and straight into a Japanese fighter, which attacked and damaged the VF-12 Hellcat, cutting the main battery cable and the plane’s electrical power to the cockpit, compelling the Hellcat to retire. Despite the Avenger’s comparatively slow speed and inferior maneuverability to the enemy aircraft, the remaining two planes turned to a defensive formation and came about to escape. Eight Japanese fighters suddenly dived on them with guns blazing, but Crockett undauntedly weaved back-and-forth to protect the group commander. Enemy fire broke his inner cooler and sprung the cowl flaps open.

The Japanese aircraft climbed and then dived for a second pass on 5 November 1943, and the Hellcat tangled with them, shooting down one of the enemy fighters and damaging one of the others. Japanese rounds lanced the Hellcat’s instrument panel, destroying almost everything except the magnetic compass, and shooting the throttle handle out of his hand. Glass from the hood splattered the deck of the cockpit. The damage to the panel forced Crockett to fly “blind”, and the severe injury to the port wing meant that he needed both hands on the stick. Blood flowed from a wound in Crockett’s head and rendered his goggles useless, hits in his arm covered his hands with blood, and wounds in his shoulder, knee, and leg oozed blood on the deck. The pilot could have flown into some nearby clouds for cover, but instead resolutely stayed with Caldwell until they returned to the carriers. Crockett, in his weakened condition, did not remember landing on Princeton, and he collapsed upon landing and crewmen carried him to sick bay. The Japanese fighters riddled the Hellcat with more than 268 bullets and shells, including 54 holes in the cockpit alone, and 180 in the port fuselage and wing.

“Group Commander sends to Fighter pilot Number Three X Your courage, determination and loyalty will be a lasting inspiration to me”, Caldwell messaged Crockett.

As the first planes began to return to Princeton shortly after noon, crewmen anxiously scanned the sky and counted the returnees. Rumors spread that an entire division went down, but as they made the final count, the ship learned that the battle cost her three Hellcats. One of the planes (BuNo 25946), flown by Lt. (j.g.) Madison, started after a couple of Zekes, but another enemy fighter attacked the Hellcat from behind and shot it down. The Japanese shot down two other Hellcats, (BuNo 25840), Lt. Richard E. O’Connell, USNR, of Minneapolis, Minn., and (BuNo 66011), Lt. James A. Smith III, of Richmond, Va., who also died in the fighting. In addition, the enemy downed three Avengers (BuNos 24219 and 24177), piloted by Lt. (j.g.) George F. Scott Jr., USNR, and Lt. (j.g.) William W. Fratus, USNR, respectively, and a third TBF-1 (BuNo 05920).

The ordeal exhausted the surviving aircrewmen, and Sherman ordered the ships to come about and make speed to the southward to be within range of Allied shore based fighter cover. The raid all but eliminated any major threat to the landings in Empress Augusta Bay, and helped to secure the Allied supply lines in the region.

TG 50.3, Rear Adm. Alfred E. Montgomery, built around Bunker Hill (CV-17), Essex (CV-9), and Independence, along with Sherman’s 50.4, launched a second strike on Rabaul at 0830 on 11 November 1943. Saratoga and Princeton reached a position not far from Green Island, northwest of Bougainville, and heavy weather again covered part of their approach that morning. Bunker Hill, Essex, and Independence maneuvered in an area in the Solomon Sea southeast of Rabaul as they flung their strike group against the fortress.

Planes sank destroyer Suzunami, and damaged light cruisers Agano (torpedoed) and Yūbari, and destroyers Naganami, Urakaze, and Wakatsuki. Curtiss SB2C-1s of VB-17 from Bunker Hill made the Helldivers’ first combat runs. Lt. (j.g.) Eugene A. Valencia, USNR, a Hispanic pilot of VF-9, flew an F6F-3 Hellcat from Essex and shot down a Japanese Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 0 carrier fighter over Rabaul. Valencia went on to score 23 confirmed victories during WWII and his decorations include the Distinguished Flying Cross. The attackers withdrew on southerly courses while the Japanese hurled more than 100 planes against them, but fighters intercepted and claimed to splash 35 enemy aircraft without a single loss. The Japanese withdrew their battered ships to Truk [Chuuk] Lagoon in the Caroline Islands.

Following the raids the group refueled at Espíritu Santo on 14 November 1943, and the next day stood out for Nauru. A Hellcat (BuNo 08991) launched from Princeton on the 15th but failed to return. Pownall led TF 50 in two days (18–19 November) of air attacks on the Japanese in the Gilbert Islands during Operation Galvanic—the occupation of the Gilberts. Bunker Hill, Enterprise (CV-6), Essex, Lexington, Saratoga, Yorktown (CV-10), Belleau Wood, Cowpens (CVL-25), Independence, Monterey (CVL-26), and Princeton comprised the main carriers. Eight escort carriers covered the approach of the assault shipping and the landings.

While Pownall struck those targets, Sherman’s TG 50.4 attacked Nauru in support. Princeton and her consorts refueled at a position not far from Nanomea and then steamed northeast, and covered the garrison groups while they steamed enroute to Makin and Tarawa. The carriers then (on the 19th) launched three strikes that blasted the islands and crated the runways, rendering them unserviceable. In the all-day attack, Princeton’s Hellcats splashed two Japanese fighters that attempted to interfere with the air coverage. The ship lost an Avenger (BuNo 23916), however, flown by Ens. R.S. Bates.

Princeton then supported the V Amphibious Corps against bitter resistance on Tarawa, and the landings on Abemama and Makin Atolls. On 20 November a Japanese aerial torpedo damaged Independence. Through 24 November aircraft flew 2,278 close support, CAP, and antisubmarine sorties. On the 24th Japanese submarine I-175 torpedoed and sank escort aircraft carrier Liscome Bay (CVE-56) 20 miles southwest of Butaritari Island, killing 645 men—272 men survived. The submarine escaped. The F6F-3 Hellcats of VF-1 from Barnes (CVE-20) and Nassau (CVE-16) landed on the airstrip at Tarawa as the first planes of the garrison air force on 25 November. A Hellcat (BuNo. 25822) lifted off from Princeton on the 26th but failed to return. Once the marines secured the islands a carrier group remained in the area for an additional week as a protective measure.

Galvanic included the first attempts at night interception from carriers. Lt. Cmdr. Edward H. O’Hare, Commander, CVG-6, and a Medal of Honor recipient, led two F6F-3s and one radar-equipped TBF-1 of VT-6 from Enterprise for that purpose on 26 November. The fighters flew wing on the Avenger, and the Enterprise fighter director vectored them to the vicinity of enemy land-based bombers that dropped flares and attacked TG 50.2. The fighters relied on the Avenger’s radar to close to visual range but failed to intercept the enemy, and in addition, a Japanese Betty shot down O’Hare. Two days later the Hellcats disrupted an enemy attack during the first air battle of its type, and the men involved nicknamed themselves the “Bat Team”. Princeton launched nine strikes in 19 days. The ship exchanged operational aircraft for damaged planes from other carriers, and on the 29th turned for Pearl Harbor and the west coast.

While Princeton charted courses for home on 5 December 1943, she lost a Hellcat (BuNo 40042), piloted by Ens. James B. Hill Jr. On the 11th the ship lost a trio of fighters (BuNos 04904, 08984, and 66013). Nine days later on the 20th, Princeton marked her final Hellcat (BuNo 40053), Ens. Virgil L. Nicklin, loss of the year when the plane crashed as the ship’s squadrons briefly flew ashore to NAS Puunene on Maui, T.H. The carrier meanwhile continued eastward and accomplished an availability at Puget Sound Navy Yard at Bremerton, Wash., primarily focusing on repairing some shaft vibration trouble.

On 3 January 1944, the increasingly seasoned warship steamed west, and at Pearl Harbor she rejoined the fast carriers of Rear Adm. Marc A. Mitscher’s TF 58 (formerly TF 50), including Bunker Hill, Enterprise, Essex, Intrepid (CV-11), Saratoga, Yorktown, Belleau Wood, Cabot (CVL-28), Cowpens, Langley (CVL-27), and Monterey. While Princeton trained on 11 January she lost an Avenger (BuNo 23980), piloted by Ens. Elwyn P. Eubank, USNR. On the 19th she sortied with TG 58.4, Rear Adm. Samuel P. Ginder, and also consisting of Saratoga and Langley, as part of the task force, to attack the Japanese garrisons of Kwajalein, Maloelap, and Wotje during Operation Flintlock—the occupation of the Marshall Islands. Land-based planes of TF 57, Rear Adm. John H. Hoover, also supported the landings. Princeton lost an Avenger (BuNo 24343), flown by Lt. (j.g.) J.M. Caldwell on 20 January, and a Hellcat (BuNo 08992) of VF-23 over Kwajalein on the 22nd.

Princeton launched her planes for strikes at Wotie and Taroa (29–31 January 1944) to support amphibious landings on Kwajalein and Majuro Atolls. The raids wiped-out the Japanese air strength on those islands. Light enemy antiaircraft fire hit a VF-23 Hellcat (BuNo 40166), flown by Lt. (j.g.) Buckelew, who made a water landing about ten miles east of the island but failed to get clear of his plane before it sank. Several Hellcats and Avengers circled anxiously and observed the landing, but sadly turned back for the carrier when they became convinced that the pilot failed to surface. Some of the Hellcats flew low and below their recommended speed over Wotje on the 31st in order to draw Japanese fire, which hit six of the planes. The squadron staff afterward surmised that the tactic would have been more effective if they had flown their usual tactics of steeper dives and greater speed.

Aircraft from eight escort carriers flew cover and antisubmarine patrols, and scout planes assisted naval bombardments. On 31 January marines and soldiers landed on islands at Kwajalein and Majuro. Into the first three days of February planes from TG 58.3, Rear Adm. Frederick C. Sherman, attacked Japanese aircraft and airfields at Engebi Island at Eniwetok Atoll, Marshalls. On 1 February additional landings occurred on Kwajalein, Namur, and Roi.

Rear Adm. Richmond K. Turner, Commander, Joint Expeditionary Force, TF 51, led the vessels from amphibious force command ship Rocky Mount (AGC 3). The increasing complexity of amphibious operations necessitated the use of command ships and the Marshalls marked their introduction to battle. Rocky Mount provided improved facilities for Capt. Harold B. Sallada, Commander Support Aircraft, who assumed control of Target Combat Air Patrol—a task previously vested in carriers. A Force Fighter Director on Sallada’s staff coordinated fighter direction.

Planes flying from Princeton photographed the next assault target, Eniwetok, on 2 February and on the 3rd returned and followed Sherman’s raids when they began three days of attacks against the airfield on Engebi. A Hellcat (BuNo 04938) flown by Ens. J.B. Boyd attempted to land on board Princeton’s pitching deck at 0945 on the 5th. The plane bounced over the barriers, the tail hook clearing them by about six inches, and although Boyd gave the Hellcat full gun the fighter barely cleared three other fighters parked at the forward end of the flight deck. One of the Hellcats had just taxied forward and its whirling propeller cut off the landing plane’s tail hook. The Hellcat rose and dropped its belly tank and fired all of its remaining ammunition, and then made a barrier crash landing on board Saratoga. The plane incurred minor damage but Boyd escaped unscathed. The ship also lost an Avenger to an accident. Through 7 February Rear Adm. Ginder’s task group supplemented Sherman. Princeton retired to Kwajalein on the 7th.

Capt. William H. Buracker relieved Capt. Henderson of command of Princeton on 7 February 1944. Originally from Virginia, Buracker had graduated from the Naval Academy in June 1919, and served successively in a number of ships and assignments during the interwar period. As the war clouds loomed, he served on board Enterprise, first as the carrier’s navigator (June 1939–June 1940), and then (until July 1941) as Vice Adm. William F. Halsey Jr.’s tactics officer, following which, he shifted to the admiral’s operations officer through July 1942. Buracker thus fought through the early carrier raids against the enemy-held mandated Pacific islands, the Halsey-Doolittle Raid on the Japanese home islands, and the Battle of Midway, and received the Silver Star for his “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity” during those battles. “While under constant threat of attack by air and submarine, the Task Force to which Captain Buracker was attached repeatedly steamed for protracted periods in enemy waters and in close proximity to enemy territory and bases. Largely due to his skill and determination under fire, only minor damage was suffered. In addition, he contributed materially to the marked success of the actions, through which the Task Force inflicted extremely heavy damage on Japanese installations and shipping.” Buracker had boarded the ship at Pearl Harbor and sailed as an understudy to Henderson. “I was to be a make-you-learn for a short operation prior to relieving” Henderson he later reflected.

Princeton returned to the waters off Eniwetok (10–13 February 1944), where her planes struck the beaches for the invasion force. Aircraft flew 118 sorties from Princeton’s flight deck, dropped 23 tons of bombs, and shot 13,000 rounds of machine gun ammunition in strafing attacks.

Two fast carrier groups operated to the west of Eniwetok to neutralize Japanese air and naval forces capable of defending the atoll. These operations permitted the second phase of the Marshall Islands Campaign earlier than the planned date of 10 May during Operation Catchpole—the seizure of Eniwetok. Princeton set out from her anchorage at Roi on 15 February 1944, her embarked group’s two squadrons counting 25 Hellcat pilots and 12 Avenger pilots. On the 16th and 17th, planes from TGs 58.4 including Saratoga, Langley, and Princeton, and 53.6 including Chenango (CVE-28), Sangamon (CVE-26), and Suwannee (CVE-27) supported landings on Engebi Island, and on 18 and 22 February landings on Eniwetok and Parry Islands, respectively.

Some 24 Hellcats from the carriers strafed Japanese trenches on Engebi on the 16th, along with piers and trenches on Eniwetok, and tanks and positions on Parry Island, and set fire to huts on Japtan Island. A total of 16 Avengers (out of 17 launched) flew five strikes and dropped 134 100-pound bombs on trenches and foxholes on Engebi and 36 100-pound bombs in similar targets on Eniwetok. On Strike 1A a VF-23 Hellcat, piloted by Ens. R.F. Cox, USNR, pulled out from about 1,200 feet from a glide run over Engebi but got hit by a machine gun bullet in his lower jaw. Despite a considerable loss of blood, Cox brought his plane back to Princeton and landed safely. A bullet shattered the panel in an Avenger’s cockpit cover over Engebi that day, though the plane also returned to the carrier.

An Avenger (BuNo 25212), flown by Lt. (j.g.) Spear, USNR, took off at 1442 on the 20th to act as the air coordinator for that afternoon’s strike. The plane’s engine failed to give sufficient power to remain airborne long enough to return to the ship, and the runway on Engebi appeared still too rough to risk a landing there. Consequently, the Avenger landed in the water close aboard Hazelwood (DD-531), and the destroyer lowered a boat and rescued the entire crew, all three of whom survived without injuries. The airmen later transferred to Cummings (DD-365), which returned them to the carrier. The following day on the 21st, the ship lost a Hellcat (BuNo 40136) over Eniwetok.

The air group reported that they required at least 50 per cent spare pilots during these battles but consistently fell short of the mark. Fighting Twenty-three reported on board with 25 pilots, “only 23 of whom were effective”. On more than one occasion, the squadron flew 12-plane patrols followed, after a brief period, by another 12-plane patrol. This compelled the men to fly seven or more hours on a single day with very little rest between flights, and contributed greatly to their “incipient staleness” and fatigue.

Lt. Cmdr. Miller furthermore commented on the morale of his men in a separate report on the strikes against Eniwetok. The “older pilots, and those with experience,” the group’s commander reflected, “always had to substitute for the youth and inexperienced who cracked first when the going got tough. This refutes the theory which is advocated by a great many that all one needs in this fighting game is a youngster with spirit and enthusiasm. Combat flying requires the same amount of experience and common sense as a professional ball club. The pilot who is matured and has the will to win always holds up where youth and enthusiasm fail”.

Princeton marked the anniversary of her commissioning by recording that she had steamed 70,701 miles during the first year of service, and launched 44 air strikes that dropped 440,000-pounds of bombs and torpedoes on the enemy. The carrier continued in the battle until the 28th, and came about and retired to Majuro, where she anchored (1–16 March), and then moved to Espíritu Santo to replenish and hold carrier qualification landings. On 23 March, the ship turned her prow to sea and headed westward for strikes against enemy installation and shipping at the Palaus, and at Ulithi, Woleai, and Yap in the Western Carolines. CVG-23 set out on Princeton with 29 Hellcat and 16 Avenger pilots. The group flew in 11 Hellcats and eight Avengers from Luganville Field on Espíritu Santo, which raised the number of aircraft on board to 25 F6F-3s and nine torpedo bombers (two TBF-1s, three TBF-1Cs, and four TBM-1Cs).

Princeton lookouts sighted four to six Bettys circling the formation at low altitude at a range of about 12 miles near sunset on 29 March 1944. The ship tracked the bombers until they disappeared, but numerous radar reports flooded in. About an hour later, some aircraft attacked the group and another ship splashed one of the intruders, which fell burning into the sea about 3,500 yards of Princeton’s starboard quarter.

Immediately thereafter, a Japanese twin-engine plane attacked Princeton on her port quarter. Ships in company opened fire and set the attacker’s right engine ablaze but it plunged toward the carrier as if it intended to carry out a suicide dive. The after 40-millimeter and 20-millimeter guns splashed the attacker barely 400 yards away and it crashed in flames. The two enemy aircraft burned on the water and illuminated the ship, presenting her as a target. The director failed to detect a third plane when it therefore attacked the ship on her port quarter. As the plane passed along her port side and crossed the bow, one of the 40-millimeter mounts and seven of the 20-millimeter guns, the latter firing special night battle ammunition (not tracer), opened fire but apparently missed the attacker. The Japanese aircraft shot a burst of machine gun fire over the planes parked on the flight deck and then winged off.

Vice Adm. Mitscher led the 11 carriers of TF 58 in a series of attacks that kicked off on 30 March. Planners intended for these strikes to eliminate Japanese opposition to landings at Hollandia on northern New Guinea, and to gather photographic intelligence for future battles. Three of the carriers, Bunker Hill, Hornet (CV-12), and Lexington, launched TBF-1C and TBM-1Cs from VTs 2, 8, and 16 that sowed extensive minefields in the approaches to the Palaus in the first U.S. large scale daylight tactical use of mines by carrier aircraft.

Princeton sent Hellcats aloft in the pre-dawn darkness for a combined fighter sweep with Lexington’s planes over the airfield on Peleliu. The ship’s Hellcats failed to rendezvous with those from Yorktown, however, and proceeded independently to the target. The Hellcats observed five Zekes airborne and splashed two of them, and the remaining three disappeared in the clouds. The American fighters then strafed Japanese aircraft parked along the runways and in revetments, setting six planes afire and holing another ten. That night at 1750, a single-engine plane, possibly a Tony, flew over the task group on a westerly course at an altitude of 20,000 feet. The Tony most likely flew a reconnaissance mission and continued on its way.

The ships launched another strike in the grey, somber pre-dawn of 31 March 1944. A dozen Hellcats lifted off from Princeton for CAP and on one of the fighter sweeps over the airfield on Peleliu at 1130 on the 30th. The weather was three tenths cloud cover with unlimited visibility. Two of the planes suffered engine malfunctions and returned to the ship, but the rest headed toward Palau to join aircraft from the other carriers. Division 1, led by Lt. Cmdr. Miller with Ens. Lawrence F. McWilliams, USNR, as his wingman, reached the airfield at 1240 as the sun shone brightly over the battle and dived to the attack from 11,000 feet. Two of the Hellcats, piloted by Lt (j.g.) Syme, and Ens. Frederick James, USNR, claimed shared credit for splashing a Betty as they dropped from above and shot up the bomber’s engines and wing root.

Division 2, led by Lt. Claude C. Schmidt, USNR, sighted a flight of 15–20 Zekes flying at an altitude of 3,000 feet about five miles away. Schmidt warned Miller by radio, and the Hellcats of Division 1 broke off their strafing runs and climbed to give battle. As the opponents tangled, the Hellcat (BuNo 40653) flown by Syme maneuvered before a division of four Zekes flying above and to the side of the main formation, apparently because Syme failed to spot the additional enemy fighters. One of the enemy fighters lunged for the F6F-3’s tail, but Schmidt’s division dived in and downed the A6M. The Hellcats pulled up and splashed two of the remaining three Zekes.

The rival formations split up as the battle degenerated into a series of dogfights, during which the Japanese shot down Syme’s Hellcat over the southwest part of the lagoon and savagely shot and killed the pilot as he fell to earth in his parachute. The enemy also downed another Hellcat (BuNo 25952), Lt. (j.g.) Joe M. Webb, who also perished. A Hellcat’s engine failed while returning from Strike 3C and the pilot ditched in the water. Stanly rescued the man and returned him to Princeton on 2 April.

A Hellcat piloted by Ens. John R. Hill Jr., USNR, claimed to splash up to three enemy fighters in the dogfighting, and two flown by Lt. Abell and Ens. James each claimed to splash a Zeke in the air and destroy a second fighter on the ground. James also claimed another Zeke in the dogfighting, and shared in the victory against a Betty. Enemy light antiaircraft fire hit two Hellcats, and they, along with three others, experienced some anxious moments as they returned to the carriers low on fuel, and finally landed on board Bunker Hill. One plane touched down with only three gallons of fuel remaining, and another with barely eight. Fragments entered the cockpit of a Hellcat flown by Ens. George B. Muhlfeld, USNR, of Englewood, N.J., and struck him in his head and fractured his leg. Despite Muhlfeld’s loss of blood, he stoically landed on Princeton’s flight deck, slammed into the barrier, but survived. The Japanese fighters that Princeton’s planes splashed also included at least one Kawasaki Ki-45 (Toryu) Nick and a Hamp. CVG-23’s planes claimed to shoot down 17 Japanese aircraft (plus one probable) in the air.

A special flight of four Hellcats later escorted a pair of Vought OS2U-3 Kingfishers from Observation Squadron (VO) 6 flying from battleship Alabama (BB-60) that unsuccessfully searched for Syme in the hope that he survived his descent. “The promptness with which the OS2Us were dispatched on this search,” Miller reported, “and the fact that the search was conducted both within and outside Palau Lagoon, has had a most beneficial effect on pilot morale.”

Planes flying from Princeton dropped 11½ tons of bombs. The raids continued until 1 April 1944, and altogether claimed the destruction of 157 Japanese aircraft, sank destroyer Wakatake, repair ship Akashi, aircraft transport Goshu Maru, and 38 other vessels, damaged four ships, and denied the harbor to the enemy for an estimated six weeks. Despite Miller’s earlier admonishment concerning the younger men under his command, he reported that the “performance of Air Group 23 throughout this operation has been of an exceptionally high order, both in combat and in routine operations”. The force replenished at Majuro, though Princeton lost a Hellcat (BuNo 66094) en route to Majuro on the 3rd.

Mitscher’s TF 58 next supported the assault of the Army’s I Corps at Aitape and Tanahmerah Bay (Operation Persecution) and at Humboldt Bay on Hollandia (Operation Reckless) on the north coast of New Guinea. Princeton and her escorts sortied again on 13 April 1944, and on the 21st five heavy and seven light carriers launched preliminary strikes through foul weather on Japanese airfields around Hollandia, Sawar, and Wakde. Planes from Princeton attacked the Cyclops Airdrome, situated near other airfields at Hollandia and Sentani to the west of Humboldt Bay. The ship’s strike group dropped fragmentation clusters, incendiaries, and 100-pound bombs against the runway and dispersal area, and strafed the runways and dispersal points. The attackers started some fires but because of the smoke, and because several groups attacked the same area and damaged many of the aircraft, could not make accurate battle damage assessments. The following day, the carriers covered landings at Aitape, Tanahmerah Bay, and Humboldt Bay, and on the 23rd Hellcats flying from the ship strafed two Japanese barges and a 125-foot boat at Matterer Bay. Three Avengers dropped nine depth bombs on, and a pair of Hellcats strafed, a concentration of troops and vehicles on the Pim-Hollandia Road. Into the 24th, the ships supported troop movements ashore.

Hellcats flown by Lt. (j.g.) Gregory J. Darby, USNR, Ens. Inmon T. Bledsoe, USNR, of Fort Worth, Texas, Ens. Lawrence O. Brugger, USNR, Ens. Hill, shared in a victory when they claimed to splash a Betty during the aerial fighting on the 24th. That busy day Bledsoe and Hill also claimed a Nick.

Planes from Chenango, Coral Sea (CVE-57), Corregidor (CVE-58), Manila Bay (CVE-61), Natoma Bay, Sangamon, Santee (CVE-29), and Suwannee flew cover and antisubmarine patrols over ships of the Attack Group during the approach, and supported the amphibious assault at Aitape. Princeton and her group then crossed back over the International Date Line to raid Truk (29–30 April). The aircraft concentrated on the Japanese seaplane station on the south tip of Moen [Weno] Island, where they destroyed three floatplanes on the ramp and damaged some of the buildings. Shortly after making these runs, Hellcats splashed a Nakajima Ki-44 (Shōki) Tojo, and a Tony dived on two Avengers but the turret gunners shot down their assailant. Princeton lost a Hellcat (BuNo 04919) over Truk on the first day of the raids.

The carriers launched a further raid against Ponape [Pohnpei] on the 1st of the month. Carrier aircraft claimed to destroy 30 Japanese planes in the air and 103 on the ground altogether during these raids. Princeton launched 548 sorties that dropped 29 tons of bombs and ripped enemy installations with more than 22,000 machine gun bullets (14 April–3 May).

Princeton returned to Pearl Harbor for minor repairs on 11 May 1944, where CVG-23 culminated its successful association with the ship as the group went ashore. The men of the two squadrons then embarked on board Altamaha (CVE-18) and traveled to NAS Alameda, Calif. (13–18 May), where they took “rehabilitation leave” before moving on to various stations for further training.

Following fighting in the South Pacific during the Guadalcanal Campaign, VF-27 had reformed on 15 October 1943, at NAS Alameda, Cmdr. Jack Roudebush in command. The squadron moved to Naval Auxiliary Air Station (NAAS) Watsonville, Calif., for additional training, while VT-27 shifted to NAAS Hollister, Calif. Both squadrons received an influx of replacements, and the Hellcat pilots qualified on board Copahee (CVE-12) off San Francisco Bay (26–29 February 1944). The following month the two squadrons united at Hollister for further training, and then (23–31 March) boarded Barnes (CVE-20) for the voyage to Pearl Harbor. From there, they flew to NAS Kahului on Maui, from which station VF-27 carried out additional training on board Midway (CVE-63) off Oahu (4–7 May). The two squadrons formed CVG-27, Lt. Cmdr. Ernest W. Wood Jr. The air group reported on board Princeton on the 14th, and the ship began loading the group’s 24 F6F-3s of VF-27 and nine TBM-1Cs of VT-27.

Fighting Twenty-seven’s time on board Princeton began less than auspiciously, however, when the squadron lost a Hellcat (BuNo 42123), Ens. G.J. McCormick, the following day. The carrier then completed an availability at Pearl Harbor Navy Yard (18–28 May), and on the 29th shoved off for Majuro, which she reached on 4 June.

There she rejoined the fast carriers and on that date as part of TG 38.3 pointed her bow toward the Marianas to support Operation Forager—landings in those islands. Princeton joined the other carriers in TG 58.3 in strikes on 11 June 1944, when she sent Hellcats for a fighter sweep against the Japanese forces on Saipan. The following day the ship began a rolling series of raids against the enemy on Guam, Rota, Tinian, Pagan, and Saipan (12–18 June). Mitscher threw some of those strikes against the Japanese garrison on Saipan 13 June, when carrier planes sank aircraft transport Keiyo Maru, which had been damaged in the fighter sweep on 11 June, and annihilated a convoy of small cargo vessels and sank Myogawa Maru, No. 11 Shinriki Maru, Sekizen Maru, Shigei Maru, and Suwa Maru. Hellcats also attacked a Japanese convoy spotted the previous day and damaged fast transport T.1 southwest of the Marianas. Hellcats of VF-27 flying from Princeton splashed a Nick at 0914 at the 12th.

Princeton planes supported the marines and soldiers when they stormed Saipan on 15 June 1944. Aircraft from an initial force of 11 escort carriers covered the landings. Japanese planes operating from ashore attacked the ships that evening at about 1820, and F6F-3s of VF-51 from San Jacinto flying CAP splashed six of seven “dive bombers” -- likely Yokosuka D4Y1 Type 2 carrier bombers, known as Judys -- approaching the carriers at high altitude. At 1909 seven twin-engined bombers -- tentatively identified as Yokosuka P1Y Frances -- attacked from ahead. Some of the attackers dropped torpedoes, at least one of which passed Enterprise close aboard to port. Carrier fighters intercepted the attackers and splashed a number of them. “I recall,” Buracker said, “that there were at least six flaming [Japanese] planes in our immediate vicinity at one time.” In addition, other ships in the formation fired antiaircraft guns and 40 millimeter rounds struck Enterprise several times, killing one man and wounding 26 others, and causing superficial damage to the superstructure. The following day on the 16th planes from Princeton struck Guam, but the Japanese downed two Hellcats: (BuNo 41484), flown by Ens. F. Kleffner, USNR, and a second F6F-3 (BuNo 42066). A destroyer rescued Kleffner and on 15 July returned him to the ship. Five Martin PBM-3D Mariners of Patrol Squadron (VP) 16 began patrolling from seaplane tender Ballard (AVD-10) within range of guns on Saipan on 17 June.

Forager penetrated the inner defensive perimeter of the Japanese Empire and thus triggered A-Go—a Japanese counterattack that led to the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Their First Mobile Fleet, Vice Adm. Ozawa Jisaburō in command, included carriers Taihō, Shōkaku, Zuikaku, Chitose, Chiyōda, Hiyō, Junyō, Ryūhō, and Zuihō. The Japanese intended for their shore-based planes to cripple Mitscher’s air power in order to facilitate Ozawa’s strikes—which were to refuel and rearm on Guam. Japanese fuel shortages and inadequate training bedeviled A-Go, however, and U.S. signal decryption breakthroughs enabled attacks on Japanese submarines that deprived the enemy of intelligence, raids on the Bonin and Volcano Islands disrupted Japanese aerial staging en route to the Marianas, and their main attacks passed through U.S. antiaircraft fire to reach the carriers.

Vice Adm. Mitscher’s TF 58 included Bunker Hill, Enterprise, Essex, Hornet, Lexington, Wasp (CV-18), Yorktown, Bataan (CVL-29), Belleau Wood, Cabot, Cowpens, Langley, Monterey, Princeton, and San Jacinto. The ships steamed west to intercept the Japanese fleet.

Throughout the day on 19 June 1944, TF 58 repelled Japanese air attacks and slaughtered their planes in the ensuing Battle of the Philippine Sea, in what Navy pilots dubbed the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.” Cmdr. David S. McCampbell, Commander, CVG-15, flew an F6F-3 from Essex and splashed at least seven Japanese planes. Princeton’s planes claimed 30 kills and her guns another three, plus one assist, adding to the ruinous toll inflicted on Japanese aircraft. A Hellcat flown by Lt. Warren E. Lamb, VF-27’s operations officer, sighted a flight of enemy torpedo planes winging toward Princeton, flew on their tails while reporting their approach, and then tore in and splashed at least one of them during the ensuing battle. Another Hellcat, Ens. Gordon A. Stanley, USNR, tangled with the Japanese and claimed to splash four fighters.

The Americans did not attain the victory without cost, however, as the enemy shot down Lt. Cmdr. Wood in his F6F-3 Hellcat (BuNo 42056), west of Guam. The command of Princeton’s air group devolved upon Lt. Cmdr. Frederic A. Bardshar, the commanding officer of VF-27, who then led both the group and the squadron. The ship also lost a second Hellcat (BuNo 42121, Lt. (j.g.) Vanburen Carter, USNR, also west of Guam.

While the formation steered southeasterly courses at 1036, pickets reported Japanese aircraft approaching bearing 265°, distance 53 miles. Some of the planes broke through the CAP and two Nakajima B6N1 carrier attack planes made a torpedo attack on Princeton’s starboard beam, but the ship’s guns splashed both Jills. Shortly after noon, a third Jill roared in from starboard and dropped a torpedo at the carrier. Princeton turned hard right to reduce the target angle and her guns shot off part of the attacker’s wing, and the plane crashed into the water ahead. Albacore (SS-218) and Cavalla (SS-244) sank Taihō and Shōkaku in separate attacks, respectively, and Japanese suicide aircraft narrowly missed Bunker Hill and Wasp.

The following afternoon Mitscher launched an air attack at extreme range on the retreating Japanese ships. The strike sank Hiyō and two fleet oilers, and damaged Zuikaku, Chiyōda, and Junyō. Despite the risk of submarine attacks, Mitscher ordered his ships to show their lights in order to guide the returning aircraft, thus saving lives when the planes consumed fuel. The night degenerated into chaos as pilots desperately sought carriers or ditched in the water, and after the carriers recovered the last of the aircraft, the formation turned to westerly courses. The Japanese lost 395 carrier planes and an estimated 50 land-based aircraft from Guam. The Americans lost 130 aircraft and 76 pilots and aircrewmen.

While the Americans won the Battle of the Philippine Sea the fighting continued ashore. Manila Bay and Natoma Bay (CVE-62) ferried aircraft to operate from captured airfields. On 17 June Stinson OY-1 Sentinels of Marine Observation Squadron (VMO) 4 arrived ashore, followed on 22 and 24 June by USAAF Republic P-47 Thunderbolts and Northrop P-61 Black Widows. Princeton launched planes to support the soldiers and marines, but on the 24th the Japanese shot down a Hellcat (BuNo 42083), piloted by Ens. Anson W. Munson, USNR. An OS2U-3 of VO-6 from Washington (BB-56), however, rescued Munson and returned him to Princeton.

On 29 June 1944 the Navy standardized carrier air groups and CVG-27 became Small Carrier Air Group (CVLG) 27. On Independence Day Japanese antiaircraft fire shot down a Hellcat (BuNo 42107), flown by Ens. Edward W. Lynn, USNR, over Orote, Guam. The following day the ship lost another fighter (BuNo 42112), Lt. J. R. Rodgers, USNR, over the embattled island—Rodgers was rescued. Organized resistance ended on Saipan on 9 July, and Princeton in the interim refueled and replenished.

Returning to the Marianas, Princeton again struck Pagan, Rota, and Guam beginning on 12 July 1944, then replenished at Eniwetok (9–14 July). On 14 July she stood out to sea as the fast carriers returned their squadrons to the fighting for the Marianas to furnish air cover for the assault and occupation of Guam and Tinian. The ships sent their planes aloft for four days straight to crater the runways on Guam and Rota, in order to prevent the enemy from staging their aircraft through the fields. The raiders furthermore bombed antiaircraft gun positions, military buildings, and installations. Japanese flak proved heavy and accurate, and their guns shot down one of the Hellcats (BuNo 41375) of VF-27 flying from Princeton on the 19th, and the following day a second fighter (BuNo 42164). The Americans landed on Guam on the 21st, and three days later on Tinian. Princeton logged the loss of a Hellcat (BuNo 42090) on the 28th.

On 2 August 1944, the force returned to Eniwetok and Princeton replenished, carried out upkeep, and worked on her boilers while anchored there through the 29th. CVLG-27, Lt. Cmdr. Bardshar, counted 25 F6F-3s of VF-27, still also led by Bardshar, and nine TBM-1Cs of VT-27, led by Lt. Cmdr. Sebron M. Haley Jr., USNR. The ship completed her work and then conducted a short period of training exercises. Despite liberating the Marianas, Allied planners believed that a base in the western Carolines would support the advance toward the Philippines and chose the Palau Islands. The Allies therefore carried out a series of wide-flung raids to reduce enemy strength and to divert them from the forthcoming operations.

Princeton sailed with TG 38.3 as part of TF 38 for Philippine waters on 29 August 1944. On the final day of the month the ship lost a Hellcat (BuNo 42045). Princeton crossed the equator while holding a westerly course on 1 September 1944. The carriers then (6–8 September) launched strikes against Japanese airfields and installations on Palau while en route to Philippine waters. An unopposed fighter sweep disclosed extensive damage inflicted by earlier raids. The force steamed onward and then (9–10 September) struck airfields on northern Mindanao in the Philippines. While other carriers hurled their planes against Del Monte Airfield and its environs, Princeton maintained CAP and antisubmarine patrols for the task group. The ship nonetheless lost an Avenger (BuNo 16897) on the 9th, and the next day another (BuNo 45947), flown by Ens. W.J. Burgess. On the following day, 11 September, Enterprise, Lexington, and Princeton launched aircraft that pounded the Visayas. Airplanes from Princeton struck targets as far west as Iloilo on Panay Island, as well as airfields and miscellaneous targets on Negros, Cebu, and Mactan. The raiders destroyed planes on the ground, and set fires in barracks, repair facilities, and oil storage. A Hellcat, flown by Ens. Oliver L. Scott, USNR, was forced down on Japanese-held Masbate, but rescuers retrieved the pilot from his perilous predicament.

Aircraft of TG 38.4 and four escort carriers of Rear Adm. William D. Sample’s Carrier Unit One then (15–18 September 1944) supported Operation Stalemate II—the landings of the 1st Marine Division on Peleliu. The Japanese had prepared their main line of resistance inland from the beaches to escape naval bombardment, and three days of preliminary carrier air attacks in combination with intense naval gunfire failed to suppress the tenacious defenders. The Army’s 81st Infantry Division later reinforced the marines and the final Japanese only surrendered on 1 February 1945.

Princeton returned to the attack against the Japanese forces in the Philippines when she took part in a series of strikes against Luzon, concentrating on Clark and Nichols fields (21–22 September 1944). Bardshar led the initial sweep of 48 fighters from Belleau Wood, Cabot, Cowpens, Langley, Monterey, Princeton, and San Jacinto on the morning of the 21st. The Hellcats strafed grounded Japanese planes on Nichols Field, and some of the surviving enemy fighters rose and the opponents fought a series of swirling dogfights in the skies over the airfield that continued out over Manila harbor and Cavite Island and culminated over Laguna del Ray, to the southeast of Manila.

The fighters flying from Princeton claimed to shoot down 38 Japanese aircraft with the loss of a single fighter (BuNo 43996). Lt. Lamb, who had been promoted to VF-27’s executive officer, made a forced landing on Lake Taal, about 60 miles south of Manila. Hellcats circled defensively overhead to cover Lamb as some men in a small boat, who appeared friendly, approached and spirited Lamb away. The squadron returned to the ship mournfully unaware of Lamb’s fate until he showed up in Pearl Harbor on 18 November. The pilot explained that he spent nearly seven weeks in the bush with Filipino guerilla fighters, and returned with some important intelligence information. Five Hellcats also suffered damage.

Despite the (likely) exaggerated victory claims, a problem common to all pilots, enemy aerial opposition virtually disappeared by the following day, mute testimony to the effectiveness of the raids. The strike group returned to their respective carriers, and Princeton maintainers began repairing the five holed Hellcats. An approaching typhoon compelled the Americans to cancel their planned launches that afternoon, and the vessels came about to evade the tempest.

Pausing only long enough to refuel, the ships continued their raids into the Philippines on 24 September 1944. Aircraft flew from Princeton’s flight deck to join a strike group that bombed Coron on Masbate, and made a fighter sweep over Negros and Panay. The group flew more than 700 miles to Coron and back, and off Calamian Island in Coron Bay sank Japanese flying boat support ship Akitsushima, cargo ship Kyokusan Maru and army cargo ship Taiei Maru; and damaged ammunition ship Kogyo Maru, army cargo ship Olympia Maru, cargo ships Ekkai Maru and Kasagisan Maru, supply ship Irako, oiler Kamoi and small cargo ship No. 11 Shonan Maru. Off Masbate, the planes sank auxiliary submarine chaser Cha 39 and auxiliary minesweeper Wa 7, merchant cargo ship Shinyo Maru, cargo ships No. 2 Koshu Maru and No. 17 Fukuei Maru, and transport Siberia Maru. Altogether the raiders sank 39 Japanese vessels including destroyer Satsuki. An aviator from Princeton made a forced water landing about five miles west of Milagros, and an OS2U-3 of VO-8 from Massachusetts (BB-59) later rescued the man. Not to be outdone, the Kingfisher attacked a damaged Japanese vessel and a pier as it flew the pilot to safety.

Princeton swung around and anchored at Kossol Roads, just north of Babeldaob at Palau, on the 27th. “I might say that we considered it none too secure,” Buracker recalled. “We were only about five miles from the north tip of Babelthuap [Babeldaob] Island, the largest island of the atoll and still inhabited by thousands of [Japanese troops]. Also there were submarines in the vicinity, none inside the anchorage, but some were reported in the immediate vicinity of the entrance. For several days we would use the anchorage during the daytime for logistic purposes, proceeding to sea for the nights.” Princeton thus shifted anchorages and spent the latter part of September at Ulithi for “logistic purposes”, where she took on needed provisions, stores, and replacement aircraft, certain aircraft supplies, and bombs. The reinforcements and replacements that reached CVLG-27 raised the group’s strength to 36 pilots, 18 F6F-3s, and seven F6F-5s of VF-27, and 16 pilots and nine TBM-1Cs of VT-27. A typhoon swept through the area and the warship spent two rough days while she headed out to sea and rode out the storm.

Capt. John M. Hoskins reported on board as Princeton’s prospective commanding officer while she lay at the atoll. A native of Kentucky, Hoskins had attained extensive experience in naval aviation. He served on board Memphis (CL-13) when she carried Charles A. Lindbergh home from Cherbourg, France, following his famed Atlantic crossing in 1927, and a decade later took part in the search for aviatrix Amelia M. Earhart and her crewman, Frederick J. Noonan. Hoskins then served consecutively as the air officer and the executive officer on board Ranger (CV-4) during the early days of World War II. Buracker and Hoskins attended a conference with Rear Adm. Sherman, during which they decided that Hoskins would “ride” with the ship as a passenger for the forthcoming operation, in order to better familiarize himself with the carrier prior to taking command.

Vice Adm. Mitscher then (October 1944) took TF 38 and struck Japanese reinforcement staging areas in the opening blow of the campaign to liberate Leyte in the Philippines. Princeton set out with TG 38.3 on the 5th and rendezvoused with the other three carrier task groups, and proceeded northwest. A Hellcat, Ens. Lyle A. Erickson, USNR, crashed into the water while taking off from Princeton on 8 October, killing Erickson. Aircraft from 17 carriers bombed airfields on Okinawa and other islands of the Ryūkyūs and sank 29 vessels on 10 October. The following day, planes struck airfields on northern Luzon in preparation for raids on the Japanese bastion of Formosa [Taiwan].

From 12 to 14 October 1944 the force then attacked ships, aerodromes, and industrial plants on Formosa and the Pescadores [Penghu] Islands and sank 22 vessels. The ships operated at various distances from the islands, but at times closed until lookouts sighted land on the horizon. Princeton also launched aircraft that flew photographic reconnaissance missions and obtained valuable intelligence data on the enemy forces and positions. The Americans attempted to surprise the Japanese, and although enemy reconnaissance planes sometimes detected the fleet, the carriers launched their strikes unhindered on each of the raids. Princeton recorded the loss of a Hellcat (BuNo 41382) on the 12th.

The carriers sent their strikes aloft without interference but the raids even so drew heavy Japanese aerial counterattacks. Lexington steamed seven miles from South Dakota (BB-57) when she opened fire on the first enemy plane recorded by the battleship at 0545 on the 12th. A Betty dropped chaff, a cloud of tiny, thin strips of aluminum spread as radar countermeasures also known as window, bearing 140°, range 50 miles. The chaff showed only faintly on the SK air search radar and partly deceived the U.S. defenses. Hellcats of VF-27 flying from Princeton nonetheless splashed the Betty at 0825.

On 13 October a kamikaze suicide plane crashed Franklin (CV-13), and the next day bombs damaged Hancock (CV-19), but both ships determinedly battled their damage. Late on the afternoon of the 14th, enemy torpedo bombers launched a coordinated counterattack against the fleet. The planes approached from different directions and dropped a number of torpedoes close aboard Princeton, but the carrier combed the wakes and escaped damage. The ship sent additional fighters into the air just before dark to intercept a Japanese group comprising an estimated 16 Frances’, and they radioed “Tallyho!” as they claimed to splash 13 of the attackers and damaged the remaining three, without loss. The surviving Frances’ jettisoned their torpedoes and came about and escaped in heavy weather. Destroying Japanese air power on Formosa paved the way on 14 and 16 October for USAAF Boeing B-29 Superfortress raids on aircraft plant and airfield facilities on the island. Princeton and her group came about from the strikes on Formosa and steamed to a position about 300 miles to the eastward for fuel, where they operated in what Buracker termed the “firing line” to support the landings in the Philippines.

On 14 October 1944, the carriers launched a second raid on northern Luzon, and the following day a sweep over the Manila area. These strikes in total destroyed an estimated 438 Japanese aircraft in the air and 366 on the ground, and in combination with other battles effectively cleared the skies for landings on Leyte. The Army’s 6th Ranger Battalion landed on Dinagat and Suluan Islands at the entrance to Leyte Gulf to destroy Japanese installations capable of providing early warning of a U.S. attack, on 17 October. The garrison on Suluan transmitted an alert that prompted Japanese Commander in Chief Combined Fleet Adm. Toyoda Soemu to order SHO-1—an operation to defend the Philippines. The raid thus helped to bring about the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Adm. Halsey, Commander, Third Fleet, led nine fleet and eight light carriers. Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid, Commander, Seventh Fleet, led 18 escort carriers organized in Task Units 77.4.1, 77.4.2, and 77.4.3 and known as Taffys 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Japanese shortages of fuel compelled them to disperse their fleet into the Northern (decoy), Central, and Southern Forces that converged separately on Leyte Gulf. Attrition had reduced the Northern Force’s 1st Mobile Force, Vice Adm. Ozawa Jisaburō in command, to carrier Zuikaku and light carriers Chitose, Chiyōda, and Zuihō. In the Sibuyan Sea U.S. planes attacked the Central Force, Vice Adm. Kurita Takeo in command, and sank battleship Musashi south of Luzon. Aircraft also attacked the Southern Force as it proceeded through the Sulu Sea, and sank destroyer Wakaba and damaged battleships Fusō and Yamashiro.

Princeton and TG 38.3 cruised off Luzon, and the ship launched her planes against airfields there to prevent Japanese land based aircraft attacks on Allied vessels massed in Leyte Gulf. The task group comprised four carriers: Essex (in which Sherman broke his flag), Lexington (Mitscher’s flagship), Langley, and Princeton, with CVGs 15 and 19, and CVLGs 44 and 27, embarked, respectively. Princeton lost a Hellcat (BuNo 70412) when two of the planes collided in mid-air while flying CAP, killing one of the pilots, Ens. George E. Arnot, USNR, on the 22nd.

Submarines and planes meanwhile reported the movements of the Japanese vessels toward Philippine waters, and overnight on 23 and 24 October 1944, the task group steamed to a position about 150 miles east of Manila. From that point, the carriers fueled and armed their planes overnight, and prepared for their three-fold task: first, to send a fighter sweep over Manila; secondly, to dispatch air searches about 300 miles to the eastward of the Philippines line; and thirdly, to furnish CAP and antisubmarine patrols. Princeton sounded general quarters at 0520 and set Material Condition Able. Crewmen led out fire hoses in the hangar and on the flight deck, and the cooks prepared to feed the crew at their battle stations, as the ship’s company anticipated a long stretch at general quarters.

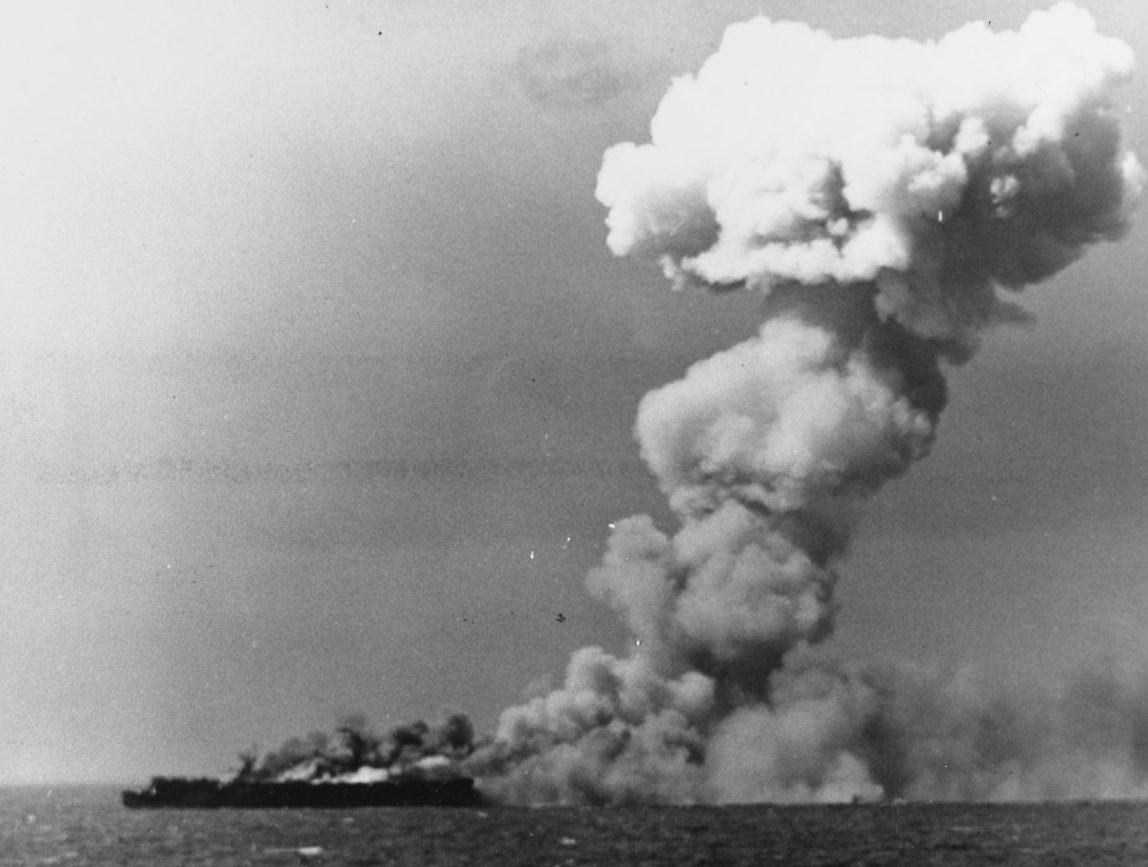

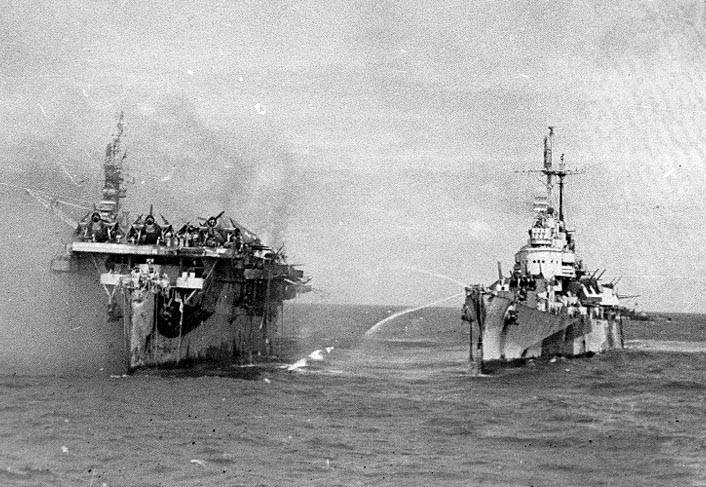

The ongoing strikes provoked a Japanese counterattack and enemy aircraft reconnoitered the formation prior to dawn on 24 October 1944, and vectored large attack groups from Clark and Nichols Fields toward the ships. Broken clouds and intermittent rain squalls that drenched the area and impeded operations punctuated the morning. Essex and Lexington launched their own search planes, and Essex sent a strike group of 20 aircraft against Japanese airfields in the Manila area. Langley and Princeton sent their aircraft aloft for patrols, beginning at 0600. Princeton launched eight Hellcats in two divisions for a CAP at 0610, and they intercepted and splashed two Japanese reconnaissance planes that attempted to reconnoiter the task group. Hellcats from Langley also claimed to splash a couple of Japanese reconnaissance planes.