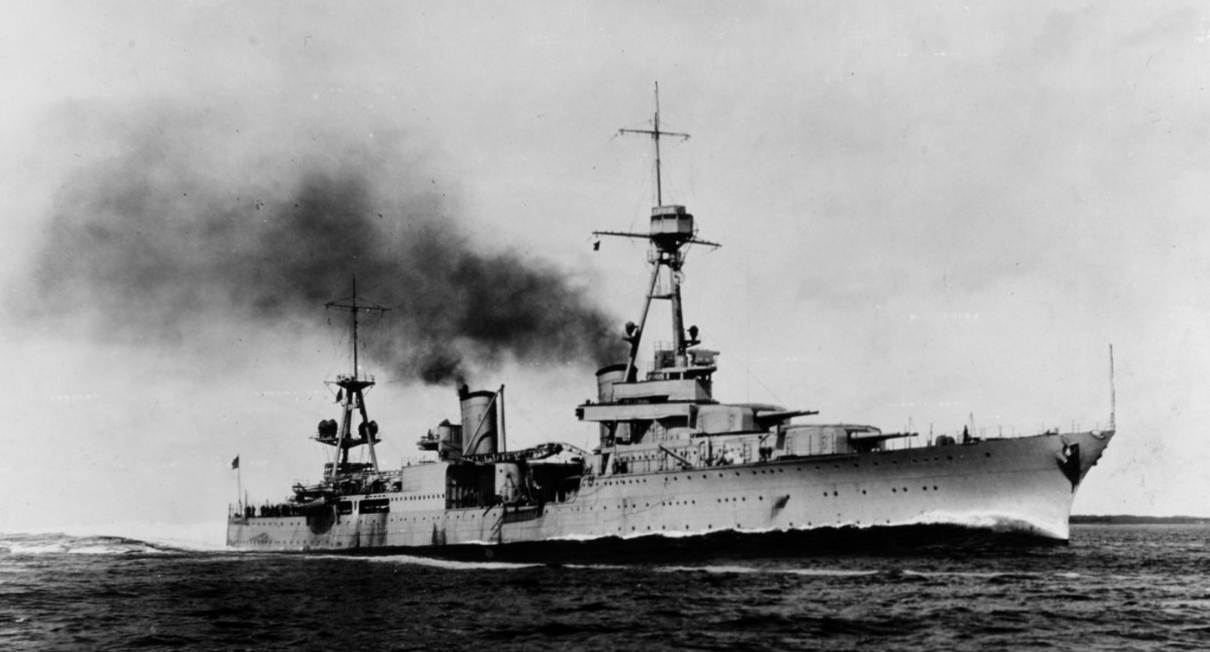

Chester II (CL-27)

1930–1959

The second ship named for a city in Pennsylvania.

II

(CL-27: displacement 9,200; length 600'3"; beam 66'1"; draft 16'4"; speed 32.7 knots; complement 574; armament 9 8-inch, 4 5-inch, 2 3-pounders (saluting); class Northampton)

The second Chester (CL-27) was laid down on 6 March 1928 at Camden, N.J. by the New York Shipbuilding Co.; launched on 3 July 1929; sponsored by Miss. Jane T. Blain, niece of Mayor Samuel E. Turner of Chester, Pa.; and commissioned on 24 June 1930, Capt. Arthur P. Fairfield in command.

Chester steamed to New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y. (25 July–7 August 1930), where she received her first aircraft, Vought O2U-3 Corsairs, as well as ammunition and stores. While underway in Massachusetts Bay on 8 August 1930, Lt. James R. Tague and AMM2c Alvin Brinkley became the first aircrew launched from Chester. On 13 August, she set out for Barcelona, Spain. Several days later, Chester received an urgent radio call for assistance from the freighter Koranton. One of the merchantman’s sailors had fallen ill and Koranton lacked a medical staff. Using the radio, Lt. Cmdr. Orville R. Goss, Chester’s medical officer, diagnosed and prescribed the proper care of the patient. Chester passed through the Strait of Gibraltar and arrived at Barcelona on 25 August.

After making a port call to Naples, Italy (2–11 September 1930), Chester set out for Istanbul [Constantinople], Turkey on 11 September. Shortly after leaving port, she intercepted a radio message announcing that the Mount Stromboli, a volcano on the Italian island of that name, had erupted. Chester’s course passed near Stromboli so Capt. Fairfield sent a message to the Italian government asking if his ship could be of any assistance. When the cruiser arrived at Stromboli, Fairfield received a message that assistance was not required. Chester resumed steaming for Turkey. Before she arrived at her destination, Fairfield received a personal message from Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini thanking him for the captain’s offer. Chester arrived at Istanbul on 15 September and remained in port until 22 September 1930. After spending five days at Athens (22–27 September) she steamed for a short visit to Gibraltar, British Crown Colony (1–2 October) before she put out for the U.S. on 3 October 1930.

Chester stood into Chester, Pa., on 13 October 1930 and opened her gangway to the public. Over the next several days, she welcomed an estimated 60,000 visitors (13-16 October). She arrived at Naval Operating Base (NOB), Hampton Roads, Va. on 17 October whence she engaged in training exercises before she put into the Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Va. (20-29 November) Chester began her final acceptance trials in the Hampton Roads on 29 November and successfully completed on 2 December 1930. She reentered the yard where she remained undergoing post-shakedown repairs and alterations until 4 March 1931. After coming out of overhaul, Chester became the flagship for the Scout Fleet’s Light Cruiser Division. With Secretary of the Navy Charles F. Adams embarked, Chester set course for Cristobal, Panama, for the annual fleet problem. She transited the Isthmus of Panama on 13 March after which Secretary Adams transferred to the battleship Texas (BB-35) to observe the fleet maneuvers in Panama Bay. Adams returned to Chester at the conclusion of the evolution and she departed for Miami on 19 March 1931. After delivering the secretary to his destination, Chester steamed to Guantànamo, Cuba. She participated in multiple exercises in the Caribbean (12 March – 28 April) before returning to Hampton Roads on 7 May. Chester stood into the New York Navy Yard on 9 May for another overhaul that lasted until 13 June 1931. After a few weeks of gunnery and training exercises (1–30 June), she was reclassified as a heavy cruiser, CA-27, on 1 July 1931.

For the next several months, Chester was busily engaged in tactical and gunnery exercises in Narragansett Bay, Hampton Roads, and the Southern Drill Grounds (1 July – 30 October 1931). On 14 October, Chester rendezvoused with French heavy cruisers Duquesne and Suffren to escort them to Yorktown, Va. (20 October). After returning to sea for more exercises, Chester returned to New York to embark Gen. John J. Pershing and his staff for transport to Newport, R.I. (24–26 October). Pershing disembarked on 27 October and Chester got underway for Hampton Roads for more exercises on the Southern Drill Grounds. She put into the New York Navy Yard (18 November 1931 – 4 January 1932) for overhaul.

After her overhaul, Chester put to sea on 4 January 1932 for winter exercises (14 January – 18 February) in the Caribbean. After operating in the Hampton Roads (5–9 January), Chester arrived at Guantànamo on 14 February. At the conclusion of the exercises on 18 February, Chester departed Cuba for San Diego, Calif., via the Panama Canal (21 February) to participate in Fleet Problem XIII (9–20 March). She stood into San Diego on 7 March. Chester took part in multiple training exercises as well as serving as the referee ship during Battle Force Practice (4–11 April). She returned to Hampton Roads on 11 May then steamed to the New York Navy Yard (13 May) where she remained until 29 July. After loading ammunition and embarking aircraft (30–31 July), Chester proceeded to San Pedro, Calif., on 1 August to rejoin the Scouting Fleet. She spent the remainder of 1932 operating in the waters off Southern California.

The cruiser stood out of San Pedro on 23 January 1933 for her first port call at Honolulu, T.H. After spending a few days in port at Honolulu (1–6 February), she steamed for San Francisco to participate in Fleet Problem XIV (17-27 February) before returning to San Pedro on 28 February. Chester operated out of San Pedro conducting training and tactical exercises before departing for the Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Wash., on 17 May via San Francisco (23–29 May). After a period of upkeep and repair at Bremerton, Chester conducted training in Puget Sound (16-30 June) before mooring at Everett, Wash. (1–10 July) She returned to her routine operations at San Pedro (21 July–23 October). She put into Mare Island Navy Yard, Vallejo, Calif. (1–2 December) then returned to San Pedro to close out the year 1933.

For the next several months, Chester operated out of San Pedro along the entire western seaboard leaving the area only once in late April for Fleet Problem XV (19 April – 12 May 1934) in Hawaiian waters. During the exercise, Chester and Houston (CA-30) squared off in a 35-minute gun battle. Capt. Martin K. Metcalf, Chester’s commanding officer, called the duel to a halt to allow recovery of her observer aircraft. Referees determined that both ships had received only minor damage in the fray. Chester returned to the Atlantic seaboard after making port calls at Gonaives, Republic of Haiti (14–15 May) and Havana, Cuba (15-26 May). She visited New York to take part in a Presidential Naval Review (31 May) before mooring at Philadelphia on 1 July 1934. After visits to Newport (11 July), and Provincetown, Mass. (12–19 July), Chester returned to the New York Navy Yard for overhaul (20 July – 13 October). Chester made her way back to San Pedro on 9 November after stopping at Guantañamo (19–20 October), Gonaives (21–22 October), Cristobal (23–24 October), and Balboa (25–29 October 1934).

Chester spent the winter of 1935 operating close to home until putting in to Pearl Harbor for Fleet Problem XVI (29 April – 31 May 1935). During exercises on 19 May, Black Fleet submarines sank Chester in a simulated attack. The attack also damaged five other cruisers. On 25 September 1935, Chester embarked Secretary of War Patrick J. Hurley to tour the western Pacific and to attend the inauguration of the first President of the Republic of the Philippines, Manuel J. Quezon. The Bureau of Insular Affairs chief, Brig. Gen. Creed F. Cox and Colonel Campbell B. Hodges also embarked to accompany the secretary on the voyage. Prior to putting into Manila, P.I., on 2 November 1935, Chester carried the secretary to Honolulu (1-4 October), Yokohama, Japan (14-17 October), Shanghai, China (21-24 October), and Hong Kong, British Crown Colony (28-30 October). While at Manila, Chester hosted U.S. Vice President John N. Garner, Rep. Joseph W. Byrns, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, and, U.S. High Commissioner to the Commonwealth of the Philippines William F. Murphy. (15 November 1935). Following the inauguration on 15 November, Secretary Hurley, in Chester, departed to tour the Philippine Islands stopping at Iloilo (17 November), Cebu (18 November), Zamboanga (19 November), and Davao (20 November). At each location, the U.S. chief diplomat received local officials and dignitaries in Chester. Chester departed the Philippines for Honolulu on 20 November touching on Guam, Marshall Islands (24 November), Wake (28 November) and Midway (30 November) islands. The secretary and his party disembarked at Honolulu on 3 December and Chester proceeded to Mare Island via Hilo, T.H. (6 December) and San Francisco (11–15 December) for overhaul. (15 December 1935 – 20 March 1936)

After returning to her homeport at San Pedro (21 March 1936), Chester steamed down the coast of the Americas with the fleet to make a good will visit to Valparaiso, Chile (29 March – 2 June). While underway, she held her first Shellback initiation to welcome her Pollywogs into the Kingdom of Neptune once the cruiser crossed the Equator (20 March). Until late 1936, Chester continued to participate in training operations and exercises as she steamed along the west coast. On 20 October, she sailed from San Francisco for Charleston, S.C. to serve as an escort for Indianapolis (CA-35) carrying President Franklin D. Roosevelt on a good will tour throughout the Caribbean and South America.

During the tour, Roosevelt visited Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (22–27 November) and Montevideo, Uruguay (30 November – 3 December 1936). Although the United States was at peace at the time, serving in the Navy still had its hazards. While dining in Rio de Janeiro a chandelier fell on Sea2c Kenneth Richardson and MM1c Robert L. Muzzy. The sailors returned to the ship by ambulance. Richardson received an 8-inch gash on his scalp and Muzzy’s right hand was slightly injured. In his report, Chester’s medical officer determined the accident was not the result of any misconduct or intoxication. Once the president disembarked from Indianapolis at Charleston (15 December 1936), Chester was detached to return to San Pedro. Her return home was encumbered by heavy rain squalls in the Caribbean (17 December) and the Pacific (19 December) in addition to a fire breaking out in her motion picture room. Finally, the determined cruiser safely anchored at Los Angeles Harbor, Calif. in time for Christmas (24 December 1936). During the arduous journey home, tragedy visited the ship when BM1c William A. Holland died. His body was transferred to the Naval Dispensary at Long Beach on 26 December, the day after Christmas.

The next several years proved comparatively uneventful. She remained mostly in the waters off California making occasional return voyages to Hawaii to train or to participate in fleet problems. In 1938, she steamed to the Aleutian Islands, Territory of Alaska (T.A.) for the first time, making port calls at Valdez (7–9 July), and Yakutat Bay (10–12 July) before returning to San Pedro on 12 August. Chester returned to the Aleutians the next summer (1939) stopping at Dutch Harbor (2–5, 10–11 July), Kanaga (7–8 July), Adak (13-15 July), and Sitka (17-18 July).

As Chester sat at San Pedro (2 August 1939 – 2 April 1940) for overhaul, the world inched toward global conflagration. On 1 September 1939, Germany forces invaded Poland expanding Hitler's quest for lebensraum, territory to expand the Third Reich. Two days later, France and the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. After returning from Pearl Harbor, Chester steamed Mare Island Navy Yard on 11 May for repairs and alterations , that included the installation of ballistics shielding, additional 5-inch guns and radar, that lasted until 9 September 1940.

After putting out of San Francisco Bay, Chester once again returned to the Caribbean for training and exercises (4 October – 9 December 1940) then underwent upkeep at New York Navy Yard (19 December 1940 – 5 January 1941). After returning to Long Beach (21–27 January), Chester moved to her new homeport at Pearl Harbor (3 February 1941). On 14 May, Chester departed with the Scouting Fleet to cruise along the western U.S. (14 May – 8 June) Nearing the end of the voyage, tragedy struck Chester’s aviation detachment, Cruiser Scouting Squadron (VCS) 5 during maneuvers. On 5 June 1941, two of the squadron’s Curtiss SOC-1 Seagulls (BuNo 9959 and BuNo 9960) collided in flight over San Clemente Island, Calif.. Ens. Thomas H. Tepuni, USNR, piloting Bu.No.9959, and his passenger, RM3c Paul J. Burroughs, bailed out when their aircraft collided with Bu No 9960, flown by Ens. Jack R. Egan, USNR. Egan also jumped from his plane but his passenger, RM1c Otto H. Wilkening, was unable to exit the biplane and died on impact. Tepuni and Burroughs died in the fall. Only Egan survived the accident.

After returning to Pearl Harbor on 18 June 1941, Chester operated in Hawaiian waters until she escorted two U.S. Army Transports (USAT), Willard Holbrook and Tasker H. Bliss, to the Philippine Islands (10 October – 13 November 1941).

On 7 December 1941, Chester was steaming toward Pearl Harbor with Task Force (TF) 8, under the command of Vice Adm. William F. Halsey, Jr. after delivering Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighters from Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 211 to Wake Island when she received the news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The task force was scheduled to arrive on 6 December, but heavy seas had impeded refueling. Scouting aircraft from Enterprise (CV-6) arrived ahead of the task force while the attack was still in progress, and entered the fray defending Pearl Harbor. Halsey ordered his remaining aircraft into the air and changed course to search for the Japanese attack force. As Chester approached Oahu, her crew could see columns of smoke rising from the carnage. Surrounded by the destruction, Chester entered Pearl Harbor on 8 December 1941 and fueled from the oiler Neosho (AO-23).

After the Battle of Pearl Harbor, Chester began conducting anti-submarine patrols in the waters of the Hawaiian Islands. On 12 December 1941, Ens. George A. Whiteside struck Chester’s first blow in the war. Flying a Curtiss SOC-1 Seagull from VCS-5 attached to Chester, Whiteside spotted a submarine about 40 feet below the surface and dropped his bombs. Chester marked the location of the attack and guided the destroyer Balch (DD-363) to zero in with her depth charges. Balch eventually lost the sound contact.

The Japanese had also simultaneously attacked multiple targets throughout the western Pacific on 8 December 1941. Among these were the U.S. installations at Wake Island. The initial attack by 36 land based Mitsubishi G3M Type 96 land attack planes [Rikko] (later called Nell by allied forces) bombers caused a great deal of damage and seriously weakened Wake’s defense. Isolated, in dire need of reinforcement and resupply, the soldiers, sailors, marines, and civilians contractors readied themselves for additional attacks. On 11 December, the men successfully repelled the first assault on the island. On 19 December, Chester got underway with TF 8 for the Johnston Island area to rendezvous with TF 14 (Rear Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher in Saratoga (CV-3)) and TF 11(Vice Adm. Wilson Brown, Jr., in Lexington (CV-2)). The three task forces were moving to relieve the troops at Wake. Halsey’s assignment was to cover the approaches to Oahu while Fletcher was to stage a diversional attack to pin down the Japanese at Jaluit Atoll, Marshall Islands. Brown’s force would then protect the seaplane tender Tangier (AV-8) while she approached Wake with vital supplies and marines of the Fourth Defense Battalion. An unfortunate series of events, and command decisions, gravely delayed the relief mission. Around midnight of 22 December, a Japanese force, under the command of Rear Adm. Kajioka Sadamichi, began attacking the island. The following day [23 December], faced with no other choice, Cmdr. Winfield S. Cunningham surrendered to the Japanese. In the aftermath of their failed mission, the task forces were diverted. Chester then operated near Midway Island (23–30 December) before returning to Pearl Harbor on 31 December 1941.

After spending ten days in Hawaiian waters, Chester charted a course for American Samoa with TF 8 to support the reinforcement of American forces on the island (18–24 January 1942). She was detached from the task force and set a course for Taroa, Marshall Islands [Republic of the Marshall Islands] with Balch and Maury (DD-401) as part of Task Group (TG) 8.3 on 31 January. As the group approached Taroa, Chester launched her Seagulls to provide spotting for her guns as she prepared for her first bombardment of Japanese installations (1 February). When her aircraft drew near, the enemy opened up their anti-aircraft guns on the biplanes. Shortly afterward, Chester began her bombardment of the island. Roughly twenty minutes later, at 0737, she came under heavy attack from enemy Mitsubishi A5M4 Type 96 carrier fighters of the Chitose Kōkūtai (Air Group). Several bombs fell close to her as she retired from the area, but at 0820, she took a direct hit on the well deck inboard of the port catapult. Chester then became the focus of eight Japanese heavy bombers but she escaped further harm. Safely out of the action, and with her planes back on board, the cruiser looked after her damage and the crew. Ens. Alvin L. Ekberg, A-V(N), ACMM(PA) Israel L. Nation, Sea2c Loyd F. Cox, GM2c James D. Kirby, Y2c Robert T. Apgar, StM2c Ramon R. Taitano, AMO3c Kenneth C. Friesen, and Pvt. Robert A. Huval, USMC, were killed in the attack.

On 3 February 1942, Chester rendezvoused with TF 8 while steaming toward Pearl Harbor. While back at her home port (3–28 February), she underwent repairs and held memorial services for her fallen shipmates. During this period, she received fire control radar and her CXAM-1 (VHF) radar moved from the aft location to a forward position. Workers also installed 20-millimeter and 1.1-inch machine guns, the latter replacing her 3-inch guns, to bolster her anti-aircraft capabilities. After post-repair gunnery exercises (1–7 March), Chester stood down the channel for San Francisco, Calif., escorting the steamer President Monroe, arriving on 11 March. She stood out of San Francisco on 15 March as part of Task Unit (T.U.) 15.12 escorting the steamers President Coolidge, Mariposa, and Queen Elizabeth steaming for Nuku Hiva, Tonga Islands, French Polynesia. The convoy arrived at their destination on 27 March 1942. New Zealand light cruiser HMNZS Achilles (C.70) relieved Chester of her escort duties on 2 April. She then joined TF 17 underway for Tongatabu [Tongatapu] Island, Tonga, British Protectorate [Kingdom of Tonga]. The task force arrived at Tongatabu on 20 April 1942. Soon thereafter (20–26 April) TF 17, including Chester, departed Tonga for the Coral Sea to support raids on Tulagi in the Solomon Islands.

On the first day of the Battle of Coral Sea, 4 May 1942, Chester was maneuvering off San Cristobal, Solomon Island, in support of raids, carried out by planes from the Yorktown (CV-5) Air Group, against the Japanese forces near Tulagi. TF 11 then proceeded (5 May) to rendezvous with TF 17. On 6 May, TF 17 joined TF 11 to launch attacks the following day on enemy ships in the area of Misima Island, Louisiade Archipelago, Territory of Papua [Papua New Guinea]. On the final day of the, Chester was successful in helping repel aerial torpedo and dive-bomber attacks in the late morning of 8 May but the Japanese aircraft eventually broke through the antiaircraft barrages as well as the scout bombers employed as interceptors and fighter aircraft. At approximately 1120, torpedoes and bombs mortally wounded the carrier Lexington (CV-2). Secondary explosions ignited spilled fuel and she was soon ablaze. Lexington’s sailors abandoned ship that afternoon. Later, her fires unquenchable, she was scuttled by Phelps (DD-360). The battle inflicted heavy damages on the Navy, with the loss of the destroyer Sims (DD-409), oiler Neosho, and Lexington. Yorktown was also badly damaged when a bomb penetrated her flight deck. For the most part, Chester emerged relatively unscathed with five crewmembers injured and one seriously wounded, while 583 sailors and marines died in the Battle of the Coral Sea. Although the losses were heavy, the Allies halted the Japanese advance by sea and the enemy shifted their onslaught overland across the Owen Stanley Mountains.

On 10 May 1942, Chester embarked 478 Lexington survivors from the destroyer Hammann (DD-412). The process took over an hour using three lines transferring two men at a time. Chester then proceeded to Nuku'alofa, Tonga Islands, French Polynesia [Kingdom of Tonga] where she arrived on 15 May. She remained at Nuku'alofa until getting under way to San Diego on 19 May. In early June, Chester returned to Pearl Harbor (4–8 June) before proceeding to Mare Island where she underwent an overhaul (20 June–5 August 1942). She remained in the San Francisco area for nearly the entire month of August for post-overhaul sea trials and training exercises. On 2 September, Chester departed for Nouméa at the Free French territory of New Caledonia, escorting transports Noordan, Klipfontein, Torrens, and Tjisdane. At the end of the month (27 September), Chester sailed with Occupation Group 62.6 to screen Allied troops landing at Funafuti Atoll, Ellice Islands, British Western Pacific Territories [Tuvalu] (2–4 October).

While Chester was steaming with (TF) 64, in support of operations in the Solomon Islands, about 120 miles southeast of San Cristobal Island near 13°31'S, 163°17'E, Japanese submarine I-176 (Lt. Cmdr. Tanabe Yahachi commanding) fired two torpedoes toward the cruiser on 20 October 1942. One torpedo struck her starboard amidships and detonated while the second one crossed in front of her bow. The torpedo caused a 500 square foot rupture, caved in the entire amidship hull, and sheared the hull plating loose in several locations. Chester’s No.1 and No. 4 engines, machine shop, No.1 and No.2 generators were destroyed. Her forward engine room and No.3 fireroom was flooded. She was forced to jettison her Seagulls (BuNo 9861, BuNo 0399) due to damage while sitting on her catapults. Sea1c Leonard Gaither, USNR, MM2c Victor C. Willie, and F2c Otto K. Jackson were blown overboard. The bodies of Willie and Jackson were recovered but Gaither was never found. Sea2c William S. Morgan, USNR, CMM(AA) Kenneth E. Erwin, MM1c Otto F.E. Hopf, MM1c Arlo L. Chamberlain, MM2c Robert K. Duggins, F1c Wilbur F. Fisk, F1c Edgar M. Miller, and F1c Robert B. Horton were also killed in the attack. The hobbled cruiser remained afloat and steamed using only her No. 2 engine, because excessive vibration in the No. 3 engine compelled her crew to shut it down on 21 October, and two days later, Chester reached Espíritu Santo, New Hebrides [Vanuatu].

While Chester completed emergency repairs at Espíritu Santo, the troop transport President Coolidge struck a mine upon entering the harbor, on 26 October 1942. Chester deployed her fire and rescue teams to lend assistance to the doomed ship. After President Coolidge sank, Chester embarked 440 survivors from the fleet tug Navajo (AT-64) for transfer to Espiritu Santo. Two days later (29 October 1942), Chester got underway for Sydney, Australia, accompanied by Farragut (DD-348) and Lamson (DD-367). She put into Sydney on 8 November where she remained for repairs until returning to sea in company with Lansdowne (DD-486) for a complete overhaul at Norfolk, Va. (25 November). Her forward engine room was still out of commission and four of her boilers were operational. The damage from the torpedo knocked out Chester’s fire control radar and seriously reduced her batteries capabilities. Only capable of making 22 knots, Chester finally entered the Norfolk Navy Yard on 25 January 1943.

Once her overhaul was complete, Chester remained in the Atlantic until setting out for the Caribbean with destroyer Braine (DD-630) on 9 August 1943. The two ships set course for Port of Spain, Trinidad, British West Indies [Trinidad and Tobago] on 21 August, and then conducted training and gunnery exercises in the Gulf of Paria (23–31 August). On 1 September 1943, both vessels set a course to Mare Island via Balboa (4–6 September) and San Francisco (13 September), arriving at their destination on 15 September. After spending a few weeks at Mare Island, Chester departed independently for Pearl Harbor on 3 October 1943. She arrived on 7 October. Chester returned to San Francisco (13–16 October) and was back at Pearl Harbor on 20 October. The cruiser operated in Hawaiian water until departing for Tarawa Atoll, Gilbert Islands, British Overseas Colony [Kiribati] on 8 November 1943 with Salt Lake City (CL-25), Pensacola (CA-24) Oakland (CL-95), Hale, and Erben (DD-631). The group rendezvoused with TG 50.3 consisting of aircraft carriers Essex (CV-9) and Bunker Hill (CV-17), small aircraft carrier Independence (CVL-22), destroyers Chauncey (DD-667), Kidd (DD-661), Wintle (DE-25), Bullard (DD-660) and oiler Neshanic (AO-71) on 15 November.

Three days later, on the evening of 18 November 1943, Chester and her formation came under attack by Japanese torpedo planes 90 nautical miles southwest of Tarawa. Chester opened up her guns to protect the carriers. During the attack, Cpl. Marion V.B. Hoffman, USMC, received serious wounds to his abdomen and right arm when a shell exploded at his battle station on the forecastle. Hoffman’s injuries required surgery, but the leatherneck proved of stern stuff -- he recovered and continued to serve in Chester. In the early morning hours of 19 November 1943, Chester and her companions brought their force to bear on the enemy at Bititu Island, Tarawa Atoll, Gilbert Islands. Chester did not receive any damage in the day's action but Sea2c Emanuel V. Natalizia was struck in the right shoulder blade by a shell fragment while operating a 40-millimeter gun on the fantail. One of Chester’s Vought OS2U-3 Kingfishers, (BuNo 5439), flown by Lt. Manuel F. Blanco, USNR, of VCS-5, ran out of fuel and was unable to return to the ship. Erben recovered Blanco and his observer, ARM3c Harry G. Riley, then sank the aircraft with her guns. While supporting the landings at Tarawa on 20 November 1943, shortly before sunset, an estimated 15 Mitsubishi G4M Type 1 land attack plane [Betty] bore down on the task force. Three Bettys honed in on Essex. The cruiser and her fellow vessels providing anti-aircraft screening opened their guns on the approaching enemy. Two of the attackers crossed Essex's bow and were quickly shot down by Chester and her compatriots. A third Betty crossed Chester's fantail, through the anti-aircraft fire, then was shot down by an American fighter.

On 26 November 1943, Chester was detached from TG 50.3 to rendezvous with the battleship Maryland (BB-46) and attack transport Harris (APA-2) south of Abemama Island, Gilbert Islands [Kiribati]. After supporting the landing at Abemama (1–7 December), Chester steamed to Funafuti (9 December) where she remained in port through the New Year, with the exception of putting out for gunnery exercises that were cancelled to bad weather. For nearly the entire month of January 1944, Chester was moored at Funafuti. While in port on 5 January one of her Kingfishers (BuNo 5693), flown by Lt. Dudley W. Hillman, USNR, crashed into the port yardarm of the rescue tug ATR-44 and began to sink. The airplane was towed back to Chester and hoisted back on board, a total wreck. To make matters worse, Lt. Dwight C. Sliger, USNR, in another of her Kingfishers (BuNo 5807), bled off airspeed to avoid a collision which caused the plane to crash into the water with enough force to knock loose the port pontoon. Sliger was able to taxi back to Chester and her aircraft shop was able to make repairs. Hillman’s aircraft was transferred off the ship for transport to Pearl Harbor. Finally underway with TG 58.2 on 23 January 23 1944, Chester returned to Funafuti the following day to repair her no.2 main air pump.

With her repairs quickly completed, Chester stood out of that port on 26 January 1943 to join up with the light minelayers Ramsay (DM-16) and Preble (DM-20) near Makin Island. The three ships then proceeded together to Tarawa. From 30 January to 18 February 1944, Chester participated in multiple bombardments of Taroa and Wotje Islands in the Marshall Islands with Salt Lake City, Preble, Ramsay, Abbott (DD-629), and Hale (DD-642). On 6 February, Chester lost another two Kingfishers (BuNo 5934), flown by Lt. (j.g.) Dario M. Raschio, and (BuNo 5807), flown Lt. Hillman, when they capsized on landing -- Hillman’s second crash in a month. Hale and Black (DD-666) sank the planes by gunfire.

After completing her bombardment missions, Chester moved to Majuro, Marshall Islands (19–26 February 1944) before steaming for Kwajalein Atoll. She remained at Kwajalein from 27 February until returning Majuro on 20 March to sortie with New Jersey (BB-62) and TG 50.15 (22 March–7 April 1944). On 25 April, Chester stood out of Majuro for the U.S. for a brief overhaul at San Francisco. While underway, on 28 April, she half-masted her colors upon receiving word that Secretary of the Navy William F. [Frank] Knox had died.

Chester arrived at San Francisco on 6 May 1944 and by 22 May she got underway for duty at Adak, T.A., making arrival there on 27 May and joining TF 94. The task force then proceeded to Kuluk Bay, T.A. (31 May) TF 94 operated in Aleutian waters until clearing Attu, T.A. on 10 June to bombard the Japanese held Matsuwa Island in the Kurile Islands [Matua, Sakhalin Oblast, Russia] on 13 June. TF 94 returned to Attu (15–23 June) before returning to the Kuriles on 26 June to bombard Paramushiru Island [Paramushir, Sakhalin Oblast, Russia]. Throughout the month of July, Chester operated with TF 94 and participated in training exercises. On 8 August, she steamed with Cruiser Division (CruDiv) 5 for Pearl Harbor where she remained until proceeding to Eniwetok at the end of the month with TF 12.5.

For the next several months, Chester participated in the bombardments of Wake Island (3 September 1944), Marcus Island [Minami-Tori-Shima, Japan] (9 October) and operations against Iwo Jima (11–12 November 1944). She also supported the carriers Hornet (CV-12) and Wasp (CV-18) during aerial assaults at Luzon (18–19 October) and Samar (20 October), Philippine Islands. While standing out of Ulithi Atoll with CruDiv 5, chaos broke out in the early morning hours of 20 November. Chester heard several ships over the radio indicating they had seen a periscope 2,000 yards outside the Mugai Channel inside the atoll. At 0530, Chester’s lookouts spotted a periscope. The cruiser took evasive action in attempt to ram the submarine or, at the very least, close distance to prevent any torpedo from arming. At the same time, the destroyer Case (DD-370), attempting to evade the enemy, turned toward Chester forcing her to come hard to port. Moments later, Case collided with a midget submarine. Within minutes, the oiler Mississinewa (AO-59) was struck by a torpedo and was soon engulfed in flames. At 0900, Mississinewa rolled over and sank taking 60 of her crew to the bottom. A post war analysis determined that she was sunk by a Japanese Kaiten suicide torpedo (launched by submarine I-47 or I-36).

Chester put into Saipan, Mariana Islands [Commonwealth of the United States] on 21 November 1944. As a member of TU 94.9, she participated in the continued campaign at Iwo Jima (8, 24, and 27 December). She finished the year in port at Saipan. On 1 January 1945, Chester proceeded with TG 94.9 to bombard Chichi Jima, Haha Jima, Bonin Island [Ogasawara Guntō] and Iwo Jima. When the task group arrived at their assigned target areas (5 January) under heavy squalls, the destroyers Fanning (DD-385) and Dunlap (DD-384) spotted Japanese tank landing ship (LST) T.107 and opened fire at 0220. The auxiliary proved to be a resilient vessel. After over an hour of the concerted efforts of Fanning and Dunlop, the ship refused to go down. After she finally succumbed, the destroyers began searching for survivors. When queried by the task group commander, Rear Adm. Allan E. Smith, as to how many Japanese were captured, Fanning radioed that she “attempted to pick up survivors but they declined our invitation.” Unable to launch spotter aircraft, the task forced bombarded Chichi Jima for two hours without the benefit of being able to determine their accuracy. The group then moved toward Haha Jima and briefly bombarded the Okimura harbor before setting a course for Iwo Jima. Several hours later, Chester was bombarding Motoyama Airfield No.2 at Iwo Jima with her 5-inch battery. As she retired from the area, planes could be seen burning and ammunition dumps exploding at the airfield.

Chester continued to operate between Ulithi and Iwo Jima. After a brief period of upkeep and replenishment of her ammunition at Ulithi (26 January–9 February 1945), Chester was again underway for Iwo Jima with TF 54. During three days (16–19 February 1945), Chester pounded Japanese emplacements with a high degree of success. Working with her spotter aircraft, Chester scored direct hits on two pillboxes, silenced multiple batteries, knocking one gun out of its revetment, and destroyed automatic weapons positions. After Pensacola (CA-24) was severely damaged and burning from enemy gunfire on 17 February, Chester shifted her focus on the offending battery. Using both her main and secondary batteries, Chester silenced the enemy guns within a few minutes. One of her Kingfishers overhead reported that Chester’s last salvo landed dead center of a two-gun emplacement. With no break in the action, Chester observed two landing craft, LCI(L)s, carrying Navy Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT), scouting the shoreline for target, were under heavy enemy fire. Chester shifted her 5-inch guns to give the frogmen cover thus making her the focus of the enemy guns. One of the LCI(L)s was hit and caught fire while the second, Chester observed, was fired upon by U.S. destroyers and capsized.

On 18 February 1945, after heavy action all morning, Chester became the target of ten full minutes of concentrated fire from Iwo Jima at 1335, fragments wounding Cpl. Frederich E. Kirsch and Pfc. John Fedick, two members of her marine detachment. At 1642, a shell passed over Chester and fell 300 yards from her. No flash was seen on shore. A few short minutes later (1648), three more shells passed over her and splashed close aboard. The commander of TU 54.1.4 (CTU 54.1.4) radioed TF 52 (CTF 52) and reported “large caliber splashes” in his area. At 1700, three more shells fell near the battleship Idaho (BB-42), Salt Lake City and Chester, also with no correlated flash on the island. CTF 52 radioed the battleship Arkansas (BB-33) and cruiser Tuscaloosa (CA-37), operating on the opposite side of the island, to check their fire because overshoots and ricochets were falling on TU 54.1.4. The incoming shells stopped.

On 19 February 1945, shortly before the amphibious assault began, Chester and the amphibious force flagship Estes (AGC-12) collided while en route to their respective D-Day positions. Chester took a glancing blow to the starboard quarter. Unable to stop to assess the damage, Chester proceeded with her mission. The ship’s performance indicated she had lost her starboard screw and, as examination revealed, Turret III had received structural damage. There was concern over what could happen when the gun was fired so the turret was placed out of commission. Despite the damage, Chester silenced two more batteries, one with a single salvo, scored direct hits on three smaller guns, and took out another automatic weapons position. Having completed her fire support assignment, Chester retired from Iwo Jima and put in to Saipan on 21 February.

Chester shaped a course for Pearl Harbor on 23 February 1945, with Dunlap escorting the battered cruiser. After a few days at sea, Chester and her companion received orders to search for survivors of a downed Consolidated C-87A Liberator Express on 27 February. The aircraft, an executive transport version of the B-24 Liberator bomber, was carrying Lt. Gen. Millard Harmon, Commander of U.S. Army Air Forces in the Pacific, from Guam to Washington, D.C. Chester searched independently for the general’s aircraft but found nothing. With her fuel depleted to a point at which she could not continue, Chester abandoned the search and resumed her voyage to Pearl Harbor.

Chester arrived at Pearl on 3 March 1945 and cleared Oahu the following day for Mare Island for her periodic overhaul. On 5 March she encountered heavy seas. Afterward, her men jettisoned 560 rounds of 20-millimeter ammunition due to contamination by sea water. She arrived at Mare Island on 4 March and remained there until the conclusion of her overhaul and sea trials in the San Francisco area. While undergoing her overhaul, the fighting still raged on Iwo Jima and the battle for Okinawa began on 1 April 1945. Once she fully repaired, Chester departed Mare Island on 16 May for San Diego. She arrived at her destination on 27 May, then departed the next day in company of Hopewell (DD-681) for Pearl Harbor. The two ships arrived at their destination on 3 June 1945.

After training with Hopewell (5–8 June 1945), Chester got underway for Ulithi (11 June) where she was joined by Hudson (DD-475) steaming for waters around the island of Okinawa (21 June). The same day she departed, Okinawa was declared secure but the Japanese continued to put up tough resistance. Beginning on 22 June, Chester conducted patrols, escort duty and covered minesweeping operations continuously with TF 32 until she put in the Buckner Bay, Okinawa [Nakagusuku-wan, Okinawa] on 15 July 1945. After TF 32 was reorganized to form TF 95.3, Chester joined the new task force to lay southeast off Shanghai, China to provide air cover for the Coastal Striking Group TG 95.2 operating outside the Yangtze [Yángzĭ Jiāng] Delta (26–28 July 1945). To avoid a typhoon that was approaching Okinawa on 1 August, while she was in port at Buckner Bay, TU 95.5.29 formed and put to sea for Saipan. While conducting anti-aircraft practice at sea, Salt Lake City inadvertently placed a shell over Chester’s foremast, wounding one on her sailors.

While Chester lay off Saipan (5–7 August 1945), the Boeing B-29 Superfortress “Enola Gay” flown by Col. Paul W. Tibbets, USAAF, dropped the first atomic bomb to be used against a military target, over Hiroshima, Japan, on 6 August 1945. On 8 August 1945, Chester steamed for Adak with TU 26.6.1. The day after the ships departed, another Superfortress, “Bockscar,” flown by Maj. Charles W. Sweeney, USAAF, dropped a second atomic bomb over Nagasaki, Japan (9 August 1945). In the wake of the atomic detonations, the Empire of Japan accepted terms for surrender on 15 August 1945 ending World War II while Chester moored to buoy No.3, Berth B-6, Kuluk Bay, and TU 26.6.1 in port at Adak.

Chester departed Adak for Attu on 20 August 1945 with CruDiv 5 and Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 56 to rendezvous with the Fourth Fleet en route to Ominato Ko, Mutsu Wan, Honshu, Japan [Mutsu-wan, Aomori Prefecture, Japan]. On the day after they rendezvoused, 2 September 1945, Japanese representatives signed the official instrument of surrender on the deck of the battleship Missouri (BB-63). The newly formed task force, TF 42, arrived at Ominato Ko on 8 September to accept the surrender of Ominato naval base in the amphibious force flagship Panamint (AGC-13) on 9 September 1945. For the next several weeks, Chester patrolled Japanese waters, making port calls at Hakodate (3-4 October) and Otaru, Hokkaido (5 October) before anchoring at Ominato Ko on 8 October 1945. On 29 October, Chester embarked passengers for transportation to Pearl Harbor and departed for Iwo Jima on 30 October. After heavy seas slowed the ship, she arrived at her destination on 1 November and departed the next day transporting 700 marines back to the U.S.

Once she arrived at Pearl Harbor (10 November 1945) her original orders were to proceed to the Atlantic via the Panama Canal. Chester was reassigned to take part in Operation Magic Carpet to bring American service men back home. While at Pearl Harbor, temporary berthing was installed in the cruiser to accommodate the homebound troops. She departed for San Francisco where nearly one third of her crew, having earned enough points for early discharge, said farewell to their wartime home on 18 November. On 24 November, Chester got underway with a skeleton crew for Guam to embark more Americans returning home. She put into San Francisco on 17 December in time to celebrate the first peacetime Christmas, and New Year’s, in four years.

Chester put to sea on 14 January 1946 for the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard with orders assigning her to the Fourth Reserve Fleet. She arrived on 24 January and placed on inactive status in the reserve fleet on 30 January 1946. Initially, Chester was scheduled for disposal in February but in March, those orders were delayed due to the fact she was being considered for sale to a foreign power. From March to June, the cruiser lay berthed with the reserve fleet and on 10 June 1946, Chester was decommissioned.

Although selected in January 1947 for dismantling in the Fourth Naval District, she received a reprieve from the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO). In February 1951, the CNO ordered regular maintenance to resume on Chester. She remained in the reserve fleet for eight more years. Stricken from the Naval Register on 1 March 1959, she was sold to Union Minerals & Alloys Corp., New York, N.Y. on 11 August 1959 and removed from naval custody on that date.

Chester earned eleven battle stars for her World War II service.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Capt. Arthur P. Fairfield | 24 June 1930 |

| Capt. Martin K. Metcalf | 14 June 1932 |

| Capt. Harry J. Abbet | 12 June 1935 |

| Capt. Ezra G. Allen | 6 July 1936 |

| Capt. Walter K. Kilpatrick | 1 July 1938 |

| Capt. Mahlon S. Tisdale | 10 April 1940 |

| Capt. Thomas M. Shock | 21 March 1941 |

| Cmd. Thomas B. Dugan | 3 December 1942 |

| Capt. William H. Hartt, Jr. | 15 December 1942 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Garry W. Jewett, Jr. | 20 May 1943 |

| Capt. Francis T. Spellman | 12 July 1943 |

| Capt. Henry Hartley | 16 July 1944 |

| Capt. Laurence A. Abercrombie | 7 August 1945 |

| Cmdr. Morton Sunderland | 1 January 1946 |

John W. Watts, Jr.

11 April 2017