Lieutenant Stephen Decatur's Destruction of Philadelphia, Tripoli, Libya

16 February 1804

A 20-minute clash on 16 February 1804 conferred a lifetime of glory on Lieutenant Stephen Decatur, Jr. On that day, he led 75 sailors to snatch victory from defeat in a bold raid in the harbor of Tripoli on the coast of North Africa. The Tripolitans had captured the American frigate USS Philadelphia, which the previous October had grounded on an underwater shoal about three miles from the port. The honor of the nation and the Navy demanded redress. The Navy needed bold leaders in the early 19th century to defend America’s national interests in foreign seas. Decatur epitomized that type of officer.

Born in 1779, Decatur grew up in the bustling seaport of Philadelphia. Tales of his father’s privateering exploits during the American Revolution attracted the son to a seafaring life. He got his chance when corsairs commissioned by the Barbary States on the North African coast preyed on American merchant ships in the Mediterranean. These attacks, as well as British and French neutrality violations, prompted the U.S. Congress on 27 March 1794 to authorize construction of a navy. On 30 April 1798—the same day Congress established the Department of the Navy—Decatur became a midshipman in the U.S. Navy. The young officer’s sterling performance during a short, undeclared naval war with France assured him a position in the much-reduced, postwar Navy.

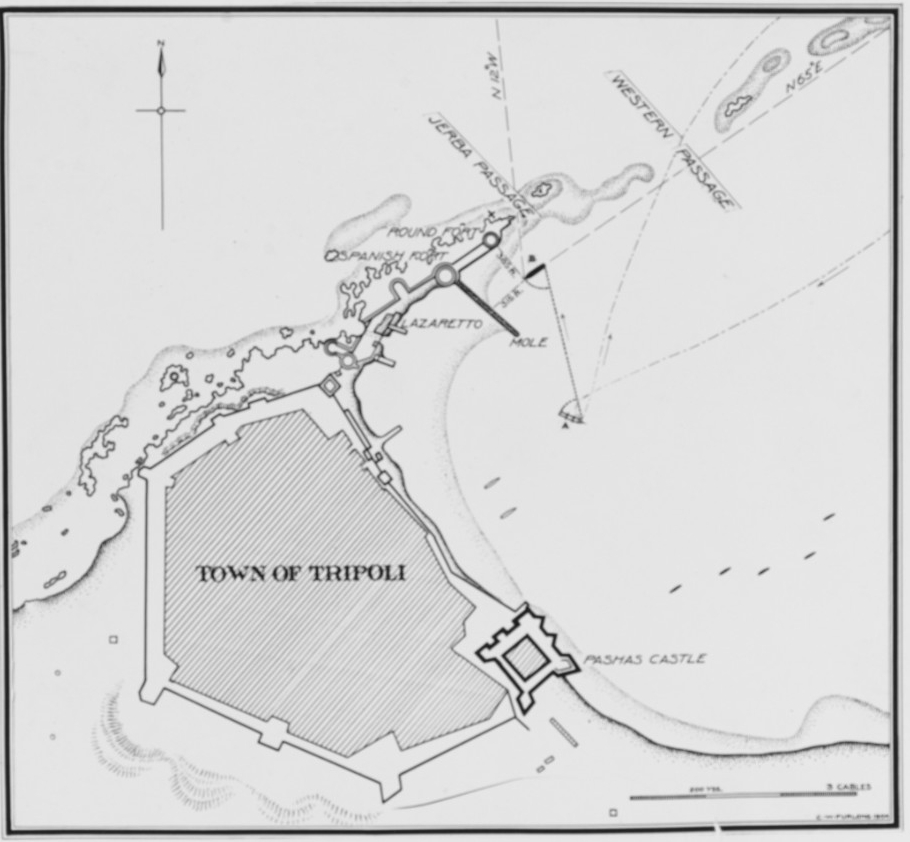

When the Barbary powers increased attacks on American trade early in the first decade of the nineteenth century, President Thomas Jefferson dispatched U.S. naval forces to the Mediterranean to counter this threat. The first two naval squadrons sent by Jefferson failed to settle the issue. When Commodore Edward Preble assumed operational command in 1803, he accelerated the war’s tempo with a more vigorous prosecution. American forces suffered a setback, however, when, on 31 October, the Tripolitans captured Philadelphia, which constituted half of Preble’s frigate strength. The Tripolitans had added a formidable asset to their arsenal.

Preble selected Decatur to command a secret expedition to board and burn the former American frigate, now anchored and protected by shore batteries and gunboats in Tripoli’s harbor, because he recognized the young lieutenant as a leader who planned operations meticulously, but also carried them out with boldness and flexibility. In addition, Preble saw that Decatur was an inspirational motivator who could rouse his men to follow him on the most dangerous missions. All of the men chosen for the operation were volunteers, thus confirming their great respect for him.

In early February 1804, Decatur and his crew of 75 crammed into a captured Tripolitan ketch, renamed Intrepid by Preble, which had been designed to accommodate only 20 or 30 men. The filthy vessel’s other passengers were rats and lice. The sailors endured the vermin and crowding longer than they expected because foul weather delayed the operation. Decatur’s constant encouragement bolstered the men’s flagging spirits while they battled gale-force winds to remain on course. On the evening of 15 February, Intrepid and its consort Siren entered Tripoli harbor, but Decatur postponed ordering the attack because he needed to verify their position. He was not dissuaded by grumbling from his sleep-deprived, malnourished crewmen, who feared discovery by the Tripolitans at any moment.

When Decatur decided on 16 February to attack, he moved with dispatch. He did not wait to augment his force with men from Siren, whose boats had not yet rendezvoused, because he feared the lack of wind might hinder his ketch from reaching Philadelphia under the cover of darkness. Trusting in his judgment, Decatur’s shipmates accepted the lieutenant’s reasoning that “the fewer the men, the greater share of honor.” Decatur’s theatricality was resplendent here in this quote from Shakespeare’s Henry V.

Decatur slowly steered Intrepid, disguised as a Maltese trader, toward the moored Philadelphia, whose small Tripolitan crew slept on deck. As the ketch approached the captured ship, Decatur’s harbor pilot, a native of Palermo, Sicily, spoke in Arabic to one of the enemy’s guards. The Italian told the Tripolitan that his ship had lost an anchor and needed to tie up to Philadelphia for the night. Just before Intrepid reached the frigate, however, the Tripolitan realized it was a ruse and exclaimed, “They are Americans!” The pilot panicked and voiced an order to board Philadelphia, but Decatur instantly countermanded him. Only when the two vessels touched did Decatur shout, “Board!” After subduing the enemy, Decatur calmed his animated men and ordered them to prepare the ship for destruction by fire. Methodically, his men placed combustible materials at each hatch from stem to stern, and, when satisfied all was ready, shouted, “Fire!” Surgeon’s Mate Lewis Heermann later recalled the scene:

Enveloped in a dense cloud of suffocating smoke, the officers and men jumped on board the ketch, and Captain D., bringing up the rear, was literally followed by the flames, which issued out of the hatchways in volumes as large as their diameters would allow.... But, notwithstanding the most imminent danger of being consumed by the devouring element they had kindled, the crew were so delighted by the “bonfire” that, perfectly careless of danger, they indulged in looking and laughing and casting their jokes. But Captain D., seeing the utmost peril of the situation, leapt upon the companion [way] and, flourishing his sword, threatened to cut down the first man that was noisy after that.

After Decatur and every one of his daring compatriots safely withdrew from the scene, word of the exploit reached Europe and the United States. This raid electrified the young American nation. Britain’s Horatio Lord Nelson pronounced it “the most bold and daring act of the age.” Preble immediately recommended his young lieutenant for a captaincy, which the Secretary of the Navy granted, making Decatur the youngest captain in the U.S. Navy at 25 years of age. That accomplishment has never been equaled.

For the remaining 16 years of his naval career, Decatur continued to embody the seamanship qualities he espoused in 1801 as a young lieutenant when addressing his ship’s company. Personal courage was primary, followed by “obedience to orders,” “fortitude under sufferings,” and a “love of country.” His inspirational rather than confrontational style led many of his men to follow him from one ship to the next. Whether in peace or war, Decatur always saw to the welfare of his crew, earning him their trust, respect, and loyalty. During the War of 1812, Decatur demonstrated exceptional courage and leadership, not only in his victory over HMS Macedonian, but also in his loss of USS President. Mortally wounded at the age of 41 in a duel with a brother officer, Stephen Decatur had already earned the reputation as the most heroic naval personage of his day and an icon in U.S. naval history.

—Christine Hughes, Histories and Archives Division, January 2019

Further Reading

Allison, Robert. Stephen Decatur: American Naval Hero, 1779–1820. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005.

De Kay, James Tertius. A Rage for Glory: The Life of Commodore Stephen Decatur, USN. New York: Free Press, 2004.

Leiner, Frederick C. “‘The Greater the Honor’: Decatur and Naval Leadership.” Naval History. 15 (October 2001): 30–34.

Tucker, Spencer. Stephen Decatur: A Life Most Bold and Daring. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2004.

Additional NHHC Resources