Native Americans Sailors in World War I

Wartime Graduates of Carlisle Indian Industrial School

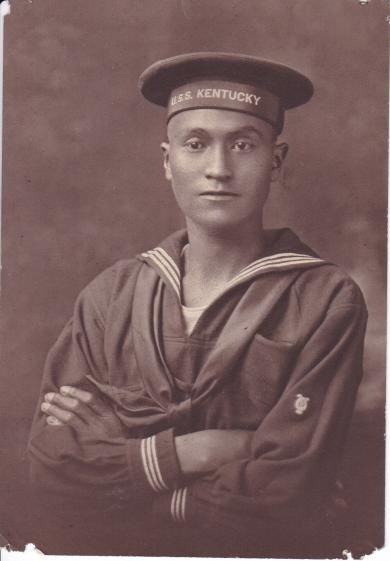

Isaac Willis, of the Ottawa Nation, Musician, Kentucky (BB-6), and a graduate of Carlisle Indian Industrial School, 1917 (Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center).

Native Americans have served with the Navy since the American Revolution. With the Continental Navy, they served as river pilots and as scouts. During the American Civil War, some enlisted in the ranks of the Union Navy. What defined their participation in World War I was their high enlistment rate for the size of their population. These recruits were the children of the age of assimilation.

Starting in the late 19th century, the agents of the Bureau of Indian Affairs removed many Native American children from their families and sent them to government-run boarding schools for their compulsory education. Carlisle Indian Industrial School was one example of these government-run boarding schools. The school opened in 1879 in Pennsylvania under the leadership of Richard Henry Pratt, an army veteran. Pratt firmly believed, “To civilize the Indian, get him into civilization. To keep him civilized, let him stay.”[1] The goal of this school and others modeled after it was the full assimilation of students as independent citizens of the United States.[2] Between 1879 and its closing in 1918, over 10,000 children attended this school. The legacy of the government-run boarding schools is sad and dark. The pictures of the children entering these schools in their tribal dress and long braids contrast sharply with images of them in their military-style school uniforms. There is no doubt that these schools indoctrinated their youth with complex feelings about their Native American heritage and the white culture that sought to eradicate theirs.

The United States entered World War I on 6 April 1917. All Native American men between ages of 21 and 30 were considered eligible for the draft under the Selective Service Act regardless of their citizenship status. The Army took the majority of those who were drafted. According to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), over 2,000 Native Americans enlisted in the Navy out of the estimated 10,000 serving in the armed forces. [3] Among those who enlisted in the Navy from the boarding schools were students from Carlisle Indian School. More than 60 students from Carlisle joined the armed forces between 1917 and 1918, and at least 14 of them joined the Navy.[4] Some dropped out prior to their graduation to join the service, with the permission of the superintendent. John Francis, Jr., was appointed as superintendent at Carlisle on 1 April 1917, only days before the U.S. declaration of war was formalized. He supported the students, both current and former, and he served at the school until its closing in 1918. Those who wrote to him at the school had their letters filed in their student files as a record of their enduring connection to the school and their service to their country.

For some of the students who enlisted in 1917, this was a chance to escape the boarding schools. For others, their decision was the natural outgrowth of patriotism forged in the classroom and a desire to prove their worth to the U.S. government. William Leon Wolfe, a student at Carlisle, was among those who joined the Navy in 1917. He later wrote, “The Indian is not a slacker, and I didn’t mean to be one.”[5] According to one reporter, most of the boarding schools were “almost emptied by enlistments when war was declared.”[6] The commissioner of Indian Affairs, Cato Sells, was excited as the rate of enlistment among the students at the boarding schools increased at the onset of this war.[7] The high number of students under the age of 21 who enlisted voluntarily seemed to be a victory for forced assimilation.

__________________________________________________________________________

“My people were proud of my determination to fight.”

—William Leon Wolfe, Chippewa.[8]

William Leon Wolfe (Little Wolf), Chippewa Nation, c. 1917 (Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center).

William Leon Wolfe (Little Wolf) was born a full-blood member of the Chippewa Nation (also known as the Ojibwe). He spent his early years at White Earth reservation in Minnesota. He arrived at Carlisle at the age of 14 in 1913. Initially, he ran from the school, only to be returned a month later. Following his enlistment in the Navy, he first served as a baker aboard Texas (BB-35).[9] In 1917, he was transferred to Utah (BB-31), where he was trained as a gunner. The battleship was assigned to patrol the waters off Ireland as the flagship of the Battleship Division 6. During his service, he gained the recognition of his captain, H. H. Hough, for his “stalwart service and ability.” Representing his ship’s division, he also won the fleet championship in lightweight boxing, which earned him the recognition of his fellow crewmembers.[10] Wolfe wrote frequently to John Francis. In letter dated 4 May 1918, he enclosed a copy of the Big U, the ship newspaper, featuring the story of his victory in the boxing championship.[11] He returned to White Earth reservation. Joseph K. Dixon, an early advocate for Native American citizenship, used Dixon’s own photograph of Wolfe in Navy uniform during congressional hearings on Native American citizenship.[12]

Thomas Montoya, of the Pueblo Nation, first arrived at Carlisle in 1911. He had been at the school for four of his five-year term in April 1914. Before Congress had made a decision to declare war, Montoya reached out to a Navy recruiting officer. [13] With his vocational training as a baker at Carlisle, Montoya was prepared to serve the Navy in that rating. Montoya’s interest in enlisting presented a potential problem for John Francis. Francis wrote to Cato Sells, the commissioner of Indian Affairs, asking for guidance on whether to allow Montoya’s enlistment prior to graduation. In response, Sells agreed with Francis that the superintendent could not oppose those over the age of 18 who wished to enlist in the armed forces. [14] Montoya told a reporter, “It’s been six years since I was home, and I expected to go this year, but now the navy needs me I’ve decided to wait.”[15] In his letters to John Francis, he expressed gratitude for his experience at Carlisle. Montoya trained at Norfolk with his classmate Luke Conley before they were both sent to Guantanamo Bay Naval Station, Cuba, for the duration of the war. Both of them were often bored in Cuba, but they felt “as proud as anyone else because we are doing our bit for Uncle Sam.”[16] Montoya was discharged from service in 1921.

Luke Conley, of the Cherokee Nation and an agricultural student at Carlisle, enlisted alongside Montoya.[17] They were part of a group of 10 students from the school recognized by the local newspapers for their enlistment in the Navy.[18] After training at Norfolk, Conley and Montoya were stationed in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.[19] Conley wrote regularly to John Francis during his service in Cuba. Francis expressed his support of his former pupil’s service to his country, including a commitment to hold money for Conley in a student savings account.[20] After the war, Conley worked as an “Indian assistant” for the Indian School Service upon his return to the Cherokee community at Big Cove, North Carolina.[21]

Edward Thorpe was born into the Oklahoma-based Sac and Fox Nation. He was one of seven children. His mother died in 1901, and his father died three years later. After their parents’ deaths, their new guardian sent Edward’s older brother Jim to Carlisle. Jim Thorpe became an athletic legend and a competitor in the 1912 Olympics. In 1913, Edward followed his brother’s path to Carlisle. That is where their paths diverged. When war broke out, Edward joined the Navy while his brother’s athletic career continued through the war. Edward served as a bugler aboard the battleship Nevada (BB-36).[22] After the armistice, Thorpe began writing letters to ensure his release from the Navy to allow his return to school. Without citizenship papers or an affidavit from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, he had no way of securing his release.[23] He was discharged in August 1919.[24] He never did go back to school. He worked as a guard for the Southern Pacific Railroad and spent the remaining years of his life in California, where he married and had two children.[25]

_____________________________________________________________________________________

In November 1917, Superintendent Francis wrote again to the commissioner of Indian Affairs. He worried that if the enlistment rate among his students continued to escalate, “the patriotic action of students” might threaten his funding from the government if he failed to meet his attendance quotas.[26] Francis received reassurance from the commissioner that enlistments would not affect funding.[27] The Senate had already conducted an investigation of the school prior to the war for mismanagement. Although the investigation seemed more concerned with the lack of discipline than the welfare of the students, Superintendent Francis could not save the school. Ultimately, the school closed its doors in 1918. Officially, its closure was a consequence of the need for the campus as a rehabilitation hospital for soldiers returning from Europe.

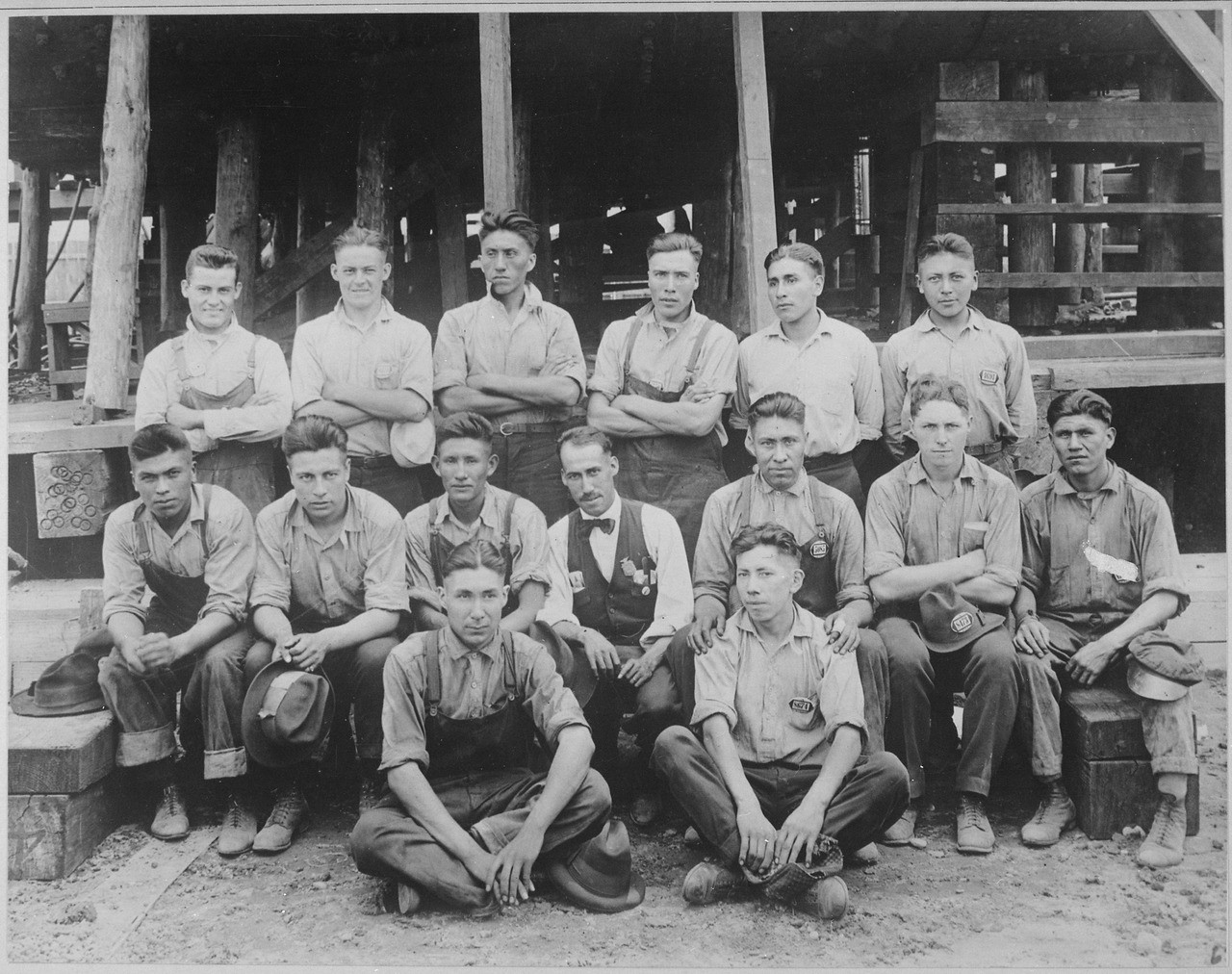

Twenty-five students from Carlisle Indian Industrial School, in Pennsylvania, worked at Hog Island shipyard during the war

(NARA 533744).

Not all of those who served the Navy during World War I were in uniform. As part of a summer outing program, Francis assigned students to work at the new shipyard at Hog Island in the Delaware River just south of Philadelphia in July 1918.[28] Guy Metoxen, an Oneida, was among those who remained at the Hog Island Shipyard after Carlisle closed in August.[29] He was not the only one. The program was part of the assimilationist agenda, but it also offered its students jobs with a need and a mission. The new shipyard, then the largest in the world, launched its first vessel in August 1918. Approximately 50 Native Americans, including 25 graduates from Carlisle, worked there during the war.[30]

Fighting the stereotype that Native Americans were best suited for farming was not easy. George W. Cushing, an Alaskan native (Aleut), was a recent graduate of Carlisle with a keen interest in automobile mechanics. His dream was to work for the Ford Motor company. After his graduation in June 1918, Cushing’s financial need and the demand for shipyard workers forced him to wait to apply to Ford until after graduation.[31] Cushing wrote to the commissioner of Indian Affairs asking for a recommendation to take the students’ course at the Ford factory in Detroit. However, the commissioner told him that his work at Hog Island was more important to the war effort. [32] Whether Cushing was asking for a recommendation or permission from the comissioner, he did not receive either one. Cushing and other former Carlisle students continued to work at the shipyard for the remainder of the war.

Overall, there were those who resisted the draft but there were others who were willing to serve. The number of Native Americans who participated in the armed forces during World War I varied greatly by tribal nation. Approximately 90 percent of male students from the government-run boarding schools enlisted voluntarily, divided between the different services.[33] The Navy did not assign Native American sailors to segregated units as the Army did. They were integrated into the service regardless of their ethnicity. Their service in World War I inspired a movement to ensure citizenship for all Native Americans.

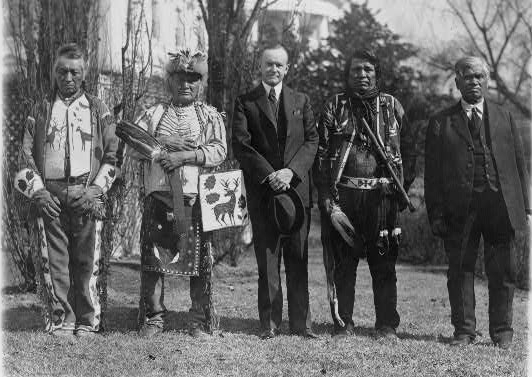

President Calvin Coolidge poses with Native American representatives on the lawn of the White House, 1924 (Library of Congress LC-USZ62-111409).

In 1919, the United States government decided to allow Native American veterans who had received an honorable discharge in World War I to apply for citizenship. This act did not result in automatic citizenship, but gave these veterans the right to apply to become citizens. Their choice to serve this government as its allies and its warriors carried the fight forward for citizenship for all Native Americans. On June 2, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge signed the act that granted citizenship to all Native Americans born in the United States. He signed this act in honor of those Native Americans who served in World War I.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

Additional Resources

“American Indians' service in World War I, 1920,” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

“Boarding Schools,” World War I Centennial (worldwar1centennial.org).

Native Americans and the Call to Serve, American Battlefield Trust (battlefields.org)

“Native Americans in the First World War and the Fight for Citizenship,” Teaching with the Library of Congress.

"Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces," Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian publication from 2021.

Further Reading

Barsh, Russel Lawrence. “American Indians in the Great War.” Ethnohistory 38, no. 3 (1991): 276–303.

Ekbladh, David, Benjamin C. Montoya, and Thomas W. Zeiler. Beyond 1917: the United States and the Global Legacies of the Great War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Harris, Alexandra and Mark Hirsch, ed. Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces. Washington, DC: National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, 2020.

Grillot, Thomas. First Americans: U.S. Patriotism in Indian Country after World War I. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018

Sabol, Steven. “In Search of Citizenship: The Society of American Indians and the First World War.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 118, no. 2 (2017): 268–71.

***

Notes

[1] Jacqueline Fear-Segal and Susan D. Rose, ed., Carlisle Indian Industrial School: Indigenous Histories, Memories, and Reclamations (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2016), 6.

[2] Richard Henry Pratt, “Why Most of our Indians are Dependent and Non-citizen,” an address delivered at the Lake Mohonk Conference, New York, Oct. 16, 1914 [PDF].

[3] United Business Service, “Information About Indians’ Military Service Invited,” United States Bulletin 1, May 19, 1919, 9. Google Books.

[4]Index by Reservation: Carlisle, Card Files Relating to Indians in World War I, Record Group 75 (Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs), box 1, National Archives Building, Washington, DC (NAB).

[5] Thomas W. Zeiler, David K. Ekbladh, and Benjamin C. Montoya, Beyond 1917: The United States and the Global Legacies of the Great War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017),116.

[6] New York Evening Sun, December 20, 1918, quoted in Russel Lawrence Barsh, “American Indians in the Great War,” Ethnohistory 38, no. 3 (1991): 279.

[7] “Information About Indians’ Military Service Invited,” United States Bulletin, Vol. 1, 1919, 9.

[8] Susan Applegate Krouse, North American Indians in the Great War (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press), 119.

[9] Student File: William Little Wolf, RG 75, Series 1327, box 118, folder 4813, National Archives Building, Washington, DC (NAB), available as digitized record through Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center (dickinson.edu); Carlisle Arrow and Red Man, Jan. 25, 1918, 3.

[10] “Thrilling Tales of Our Indians’ Gallantry in Great War,” New York Herald, September 4, 1921, 64; Krouse, North American Indians in the Great War, 127.

[11] Student File: William Little Wolf, RG 75, Series 1327, box 118, folder 4813, NAB, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

[12] House Committee on Military Affairs, Army Reorganization, vol. II (Washington, DC: GPO, 1920), 2191.

[13] Student File: Thomas Montoya, RG 75, Series 1327, box 114, folder 4700, NAB, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

[14] Correspondence between John Francis, Jr and Cato Sells, April 1917, Record Group 75: Bureau of Indian Affairs, Central Classified Files (CCF), Entry 121, 34399-1917-Carlisle-820, NAB, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

[15] Evening News (Harrisburg, PA), April 16, 1917, 7; Montoya had been at the school in Carlisle for four years, but he had attended another off-reservation school for two years prior.

[16] Student File: Thomas Montoya, RG 75, Series 1327, box 114, folder 4700, NAB, available as digitized record through Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

[17] Student Information Card: Luke Conley, RG 75, Series 1329, box 11, NAB, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center; Evening News, April 16, 1917, 1.

[18] “Indians Doing their Bit: Carlisle Students, Including Several Notable Athletes Rally to Colors,” News Journal, (Wilmington, DE), June 26, 1917, 11; “Carlisle Indian Boys in the Army and Navy,” Sentinel (Carlisle, PA), June 21, 1917, 4.

[19] “General News Notes,” Carlisle Arrow and Red Man, February 1, 1918, 4.

[20] Student File: Luke Conley, RG 75, Series 1327, box 114, folder 4701, NAB, available as digitized record through Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

[21] North Carolina State Board of Health, “North Carolina Death Certificates,” digital image, s.v. Luke Conley, 6 Feb 1942, Swain County, Ancestry.com; To learn more about this job description, see Wilbert H. Ahern, “An Experiment Aborted: Returned Indian Students in the Indian School Service, 1881–1908,” Ethnohistory 44, no. 2 (1997): 263–304.

[22] Student File: Edward Thorpe, RG 75, Series 1327, box 117, folder 4772, NAB, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

[23] Edward P. Thorpe to Assistant Commissioner of Indian Affairs, E.B. Merrit, February 1, 1919, RG 75, CCF Entry 121, #10076-1919-Carlisle-125, “Discharge of Edward Thorpe From the Navy,” NAB, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

[24] State of Pennsylvania, World War I Veterans Service and Compensation File, 1934–1948, RG 19, Series 19.91, digital image s.v. “Edward P. Thorpe,” Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, Harrisburg PA, Ancestry.com.

[25] San Bernardino County Sun, October 20, 1968, 28.

[26] John Francis Jr. to Commissioner of Indian Affairs, November 22, 1917, RG 75, CCF Entry 121, #108226-1917-Carlisle-125, NAB, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

[27] Assistant Commissioner of Indian Affairs, E.B Merritt to John Francis Jr., December 11, 1917, RG 75, CCF Entry 121, #108226-1917-Carlisle-125, NAB, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

[28] For more details about outing programs, see Robert Trennert, “From Carlisle to Phoenix: The Rise and Fall of the Indian Outing System, 1878-1930,”Pacific Historical Review 52, no. 3 (1983): 267–91.

[29] Student File: William Little Wolf, RG 75, Series 1327, box 131, folder 5180, NAB, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

[30] Thomas A. Britten, American Indians in World War I: At Home and at War (University of New Mexico Press, 1997), 147.

[31] Student File: George W. Cushing, RG 75, Series 1327, box 146, folder 5685, NAB, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center

[32] “Request of George Cushing to Attend Ford Course,” RG 75, CCF Entry 121, #82356-1918-Carlisle-920, NAB, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center.

[33] Barsh, “American Indians in the Great War,” 278.

***

This essay is currently limited to digitized historical record during the COVID-19 Pandemic. It will later be expanded to include more records and a broader historical context for the story of Native American sailors serving in World War I.