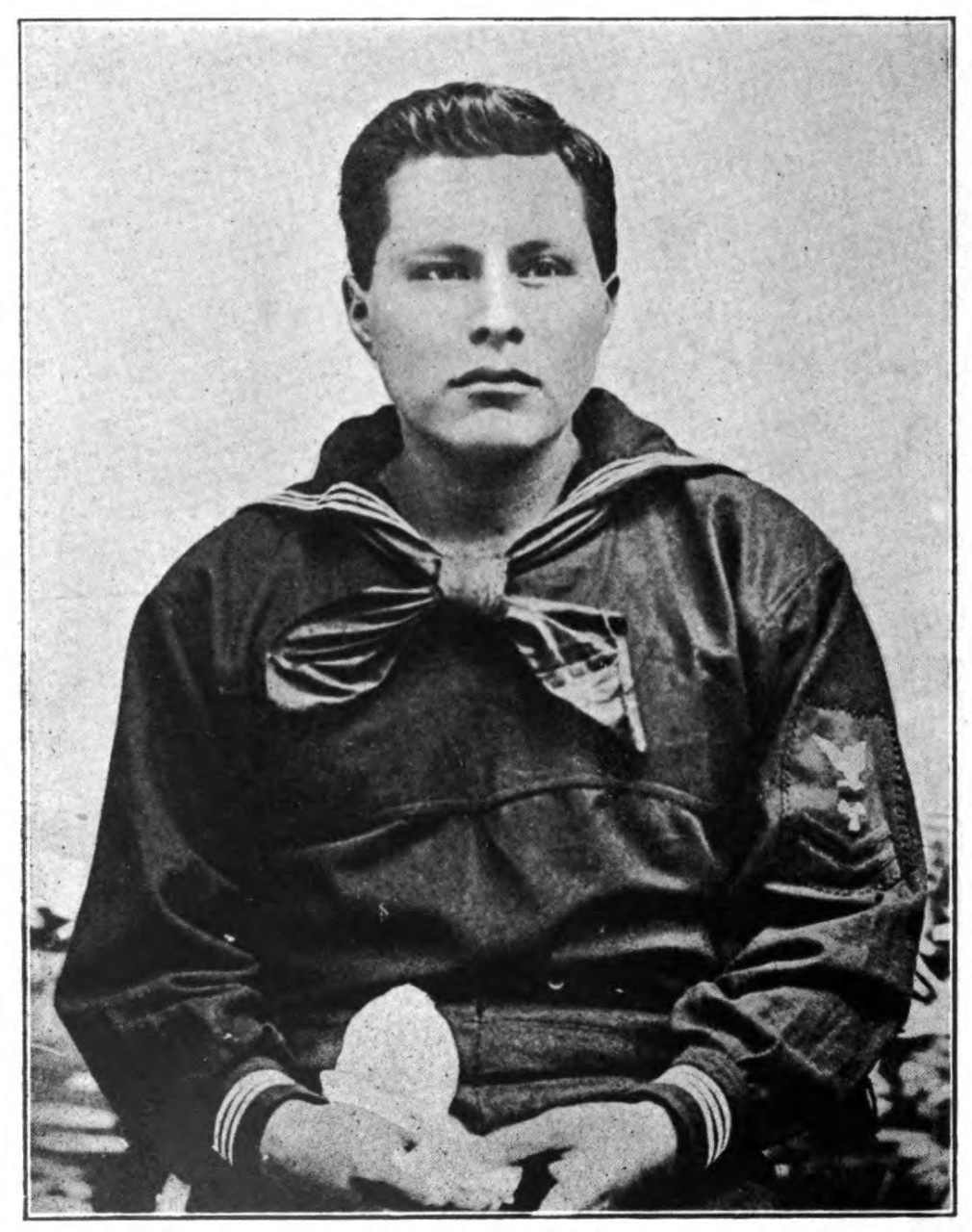

Chief Machinist's Mate Chapman Scanandoah

Har-Chico-Qui, “He Moves the Fire”

In 1870, Chapman Scanandoah was born in the Windfall community of Oneidas near the town of Lenox, New York. His name in his native language was Har-Chico-Qui, translated as “He Moves the Fire." The Oneida are one of the five founding tribes of the Hodinöhsö:ni' (Iroquois) confederacy.[1]

Scanandoah was a descendent of warriors. His ancestors were allies to the United States during the American Revolution and the War of 1812. Following this tradition of service, Scanandoah enlisted in the U.S. Navy as a machinist in 1897.[2]

He was one of the many Native Americans who has served in the United States in the Navy. His life story illustrates the Navy values of Honor, Courage, and Commitment—not only to the Navy, but to his people, through his 15 years of service.

When Scanandoah was growing up in New York, the pressure on the Hodinöhsö:ni' to give up their land and to move westward had already caused many Oneidas, including his own relatives, to leave New York for larger land grants in Wisconsin. Scanandoah and his family were among the few who remained. As their numbers dwindled, those who remained felt the need to assimilate and to seek out education for their children as a means of survival in the white society that threatened to engulf them. Starting at the age of eight, Scanandoah learned English at the local district school.[3] Inspired by the changes they saw all around them, he and his brother Albert both experimented in mechanics from a young age.[4] It was a piecemeal education, but it gave him an advantage at a time when the abilities of Native Americans were often underestimated by white outsiders.

Unfortunately, the standard of education for Native Americans during this period was far too low. The government did not subsidize the education of the children of Hodinöhsö:ni'. Opportunities for further education beyond the local district school were limited. When representatives from the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute visited nearby Syracuse, they offered an opportunity for a better education. At age 18, Scanandoah traveled with other Hodinöhsö:ni' children to enroll at the school in Hampton, Virginia. Because of the lack of a government subsidy for his education, he enrolled as a work study student, working all day and attending night school. He was forced to drop out after two years to earn money toward completing his education. Luckily, he found work with his older brother as a factory worker at Edison Illuminating, in Schenectady, New York. Speaking to the Lake Mohonk Conference in 1892, he spoke of the importance of education and his intent to return to complete his studies at Hampton. Four years later, he graduated with a certificate in mechanics.[5]

In search of steady employment with good pay during an economic depression, Scanandoah decided to enlist in the U.S. Navy. On 5 August 1897, he enlisted for a term of three years at the naval recruiting station in Chicago, Illinois.[6] He reported for duty aboard Vermont, a receiving ship stationed at Brooklyn Navy Yard.[7] The Navy soon transferred him to California where he was stationed aboard Independence, a receiving ship based at Mare Island Navy Yard.[8] Although he was initially trained as a fireman, his abilities as a mechanic were soon recognized. His first assignment to a seagoing vessel, Marietta, was as a machinist's mate second class.[9]

In March 1898, Marietta departed San Francisco with Scanandoah on board. From March to June 1898, Marietta traveled the coast of South America, from Peru to Chile to Brazil. After a short rotation as part of the blockade of Havana Harbor, Marietta was reassigned to the Philippines, but Scanandoah did not travel through the Suez Canal with his ship as he had been reassigned. In November 1898, he was part of the crew that helped to bring a salvaged Spanish prize, Sandoval, limping into Washington Navy Yard for repairs.[10] Throughout the war, Scanandoah was consistently assigned away from the actions that might have earned him accolades. Nevertheless, he proved himself to be a good Sailor and a good machinist. After the war, he received a promotion to machinist, first class. In 1899, he was assigned to the battleship New York. At the anniversary of the battle of Santiago in 1899, he was photographed with a gun crew of New York.[11]

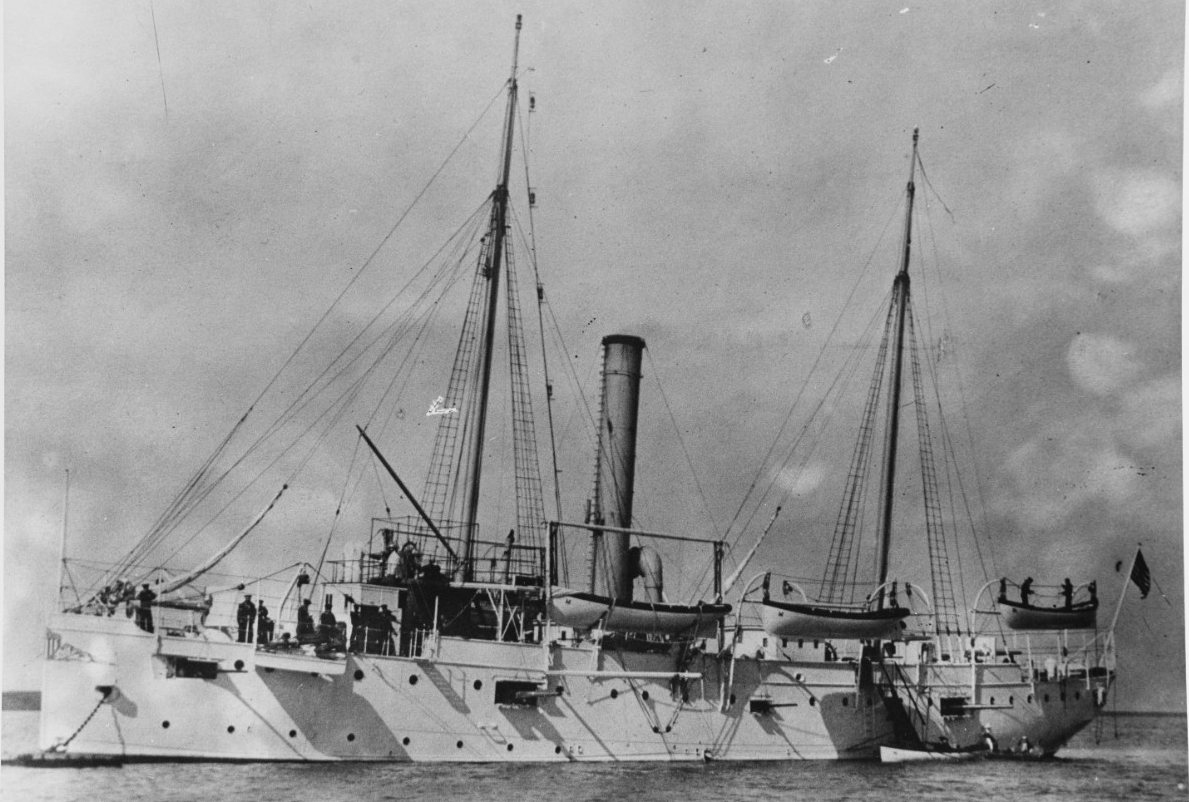

Scanandoah was officially discharged from service in August 1900, but he soon reenlisted at the end of October. He was assigned to Atlanta, which was due to leave for South America.[12] While he returned to sea for the income it provided, Scanandoah continued to be plagued by messages from home that threatened his family’s land holdings.[13] After he was denied a request for leave while on patrol, he decided that he had no choice but desertion. Scanandoah left Atlanta in port at Buenos Aires, Argentina, in the summer of 1902. He bought passage on an ocean liner from South America to New York. Soon after his arrival in New York City, he turned himself in to officials in Washington.[14] He was court-martialed and tried on 12 December 1902. Although charged with desertion, Scanandoah was granted a lesser charge of “absence without leave.”[15] Upon his return to duty, he was promoted to chief petty officer and served as chief machinist aboard the recently recommissioned cruiser Raleigh.[16] In 1903, he circumnavigated the globe aboard this ship, traveling from New York City to South America before heading east through the Strait of Gibraltar and the Suez Canal en route to join the Asiatic Fleet.[17] Over the next four years, the crew of Raleigh cruised the Pacific with few opportunities to travel back home.

On one of his rare visits back to the states, Scanandoah married Bertha Crouse, an Onondaga, in New York City, while on leave in 1905. Even after his first son was born, he reenlisted for another tour. After Raleigh was decommissioned in 1907, he received orders to Dubuque for two years. Although he was based at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, he was frequently away on patrol in the Caribbean and further south to Central America.[18] During this tour of duty, his remaining family at Windfall, including his mother, were forcibly removed from their 32-parcel following a lengthy and illegal foreclosure process.[19] His mother moved to the Onondaga reservation thirty miles west near Syracuse where Scanandoah’s wife already lived.

In 1910, Scanandoah was transferred to the Norfolk Navy Yard. He finally had the time to put the first of his inventions to paper. In December 1911, he submitted his first application to the U.S. Patent Office for a modified megaphone, which he invented specifically for shipboard use.[20] The following year, he received his second honorable discharge in August 1912 after finishing his third tour of duty. Shortly after, he received his first patent while settling back into life at home. Finally able to give his full attention to problems at home, Scanandoah renewed his fight in court for the return of his family’s land at Windfall, but it was no easy fix. The litigation over this thirty-two acres dragged on for another 10 years. Meanwhile, Scanandoah went back to work for General Electric (GE), formerly Edison Illuminating, at Schenectady, as he adjusted to life back on land.

In December 1913, Scanandoah, now a chief among the Oneidas of the Onondaga reservation, was among those who signed the “Indian Declaration of Allegiance to the United States.”[21] This controversial document was the first voluntary acknowledgement of the sovereignty of the United States government over the indigenous tribes. It was the beginning a of a movement to grant full citizenship to the Native Americans, which was ultimately granted on 15 June 1924 by an act of Congress.

For two years, both he and his brother Albert worked for GE. Unfortunately, neither his education at Hampton Institute nor his experience in the Navy prepared him to compete with college-educated engineers.[22] While employed at Schenectady, he continued to work on his own inventions. In April 1914, he applied a patent for a new invention, a new less dangerous type of explosive, which he later called “schanadite.”[23] His basic premise was that none of the components in this new composition were combustible by themselves, except when mixed together. Like his megaphone, this idea was again based on his experiences in Navy.

His time in the Navy never seemed to be far from his mind, and he did attempt to return to service during World War I. In 1915, Scanandoah left General Electric for a job at the New York Navy Yard in Brooklyn. With the looming prospect of war against Germany, he applied to reenlist in the Navy. Rejected due to his age and his need for corrective lenses, he sought any opportunity to serve the war effort. After the United States entered the war in April 1917, he went to work at the Frankford Naval Arsenal in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[24] This installation was known for its production of small-arms munitions and ordnance, which suited his interest in explosives. After the war, he returned again to the reservation to take up farming while he continued to work on his inventions. His last patent was submitted in 1926 for a new method for condensing metal.[25] Each patent application from Scanandoah was an attempt to improve upon the way things work. None of his patents were taken up by corporate America, but each patent revealed the ingenuity of a mind that never stopped working.

Chapman Scanandoah died at the age of 82 on the Onondaga reservation in Syracuse, New York, on 22 February 1953. He is remembered among his people as a “renaissance man.”[26] His 15 years with the U.S. Navy was only the beginning of his life of service to his people.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

Other NHHC Resources

Spanish-American War: War Plans and Impact on U.S. Navy

Additional Resources

“Chapman Schanandoah (Oneida),” in Emery, Jacqueline. Recovering Native American Writings in the Boarding School Press University of Nebraska Press, 2017.

Hauptman, Laurence M. An Oneida in Foreign Waters: The Life of Chief Chapman Scanandoah, 1870–1953. Syracuse University Press, 2016.

“An Oneida Renaissance Man: Chapman Schanandoah.” Oneida, Issue 7, Vol. 10 (March/April 2008).

____________

Acknowledgments

Thank you so much to Dr. Laurence Hauptman for his guidance. I am grateful to be able to share the story of this member of the Oneidas and his commitment to service. K.E.

Notes

[1] Hodinöhsö:ni' is the Seneca word for the Iroquois Confederacy, also referred to as the Six Nations or Haudenosaunee.

[2] Standard Union (Brooklyn, NY), August 12, 1897, 5.

[3] Laurence M. Hauptman, An Oneida in Foreign Waters: The Life of Chief Chapman Scanandoah, 1870–1953 (Syracuse University Press, 2016), 14.

[4] Hauptman, An Oneida in Foreign Waters, 26.

[5] Hauptman, An Oneida in Foreign Waters, 26–28; Martha D. Adams, ed., Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Meeting of the Lake Mohonk Conference of Friends of the Indian (New York, NY: Lake Mohonk Conference, 1892), 41–42.

[6] Standard Union, August 12, 1897, 5.

[7] New York State Archives, “Abstracts of Spanish American War Military and Naval Service Records, 1898–1902.

[8] Mark L. Evans, “Independence II (Ship-of-the-Line), 1814-1913,” Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships (DANFS), last modified 15 April 2015.

[9] “Only Indian in the U.S. Navy,” Boston Globe, March 4, 1901, 6.

[10] Semi-Weekly Messenger (Wilmington, NC), December 16, 1898; Southern Workman and Hampton School Record (Hampton, VA: Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute), Vol. 28, No.3, March 1899, 109

[11] Edward H. Hart, U.S.S. New York, a gun crew, anniversary of Santiago, 1899, Photograph (Detroit, MI: Detroit Publishing Company, 1899), Library of Congress, accessed October 12, 2021.

[12] “White Man’s Navy Good to Lo, Oneida Indian Shenandoah May Serve Again,” Sun (New York, NY), January 4, 1903, 8.

[13] Hauptman, An Oneida in Foreign Waters, 43–44.

[14] Hauptman, An Oneida in Foreign Waters, 44.

[15] Hauptman, An Oneida in Foreign Waters, 44.

[16] Honolulu Advertiser, December 23, 1903, 2.

[17] “Raleigh II (Cruiser No. 8,” Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships (DANFS), last modified September 16, 2005.

[18] “Dubuque I (Gunboat No. 17),”DANFS, last modified July 7, 2015.

[19] Chapman Schanandoah to Joseph Keppler, December 4, 1909, Folder S3, No. 34, Joseph Keppler Jr. Iroquois papers, #9184. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

[20]Chapman Schanandoah, Megaphone, US Patent 1040775, filed December 19, 1911, and issued October 8, 1912. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

[21] Declaration of Allegiance to the Government of the United States by the North American Indian, #9095. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

[22] Chapman Schanandoah, Explosive, US Patent 1141009A, filed April 18, 1914, and issued May 25, 1915. Google Patents.

[23] Hauptman, An Oneida in Foreign Waters, 82–5; Encyclopedia of the American Indian in the Twentieth Century (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 2015), 398.

[24] Hauptman, An Oneida in Foreign Waters, 85.

[25] Chapman Schanandoah, Explosive, US Patent 1571737A, filed April 1, 1925, and issued February 2, 1926. Google Patents.

[26] “An Oneida Renaissance Man: Chapman Schanandoah,” Oneida 10, no. 7 (March/April 2008).