Sailors Rights!

Desertion was common in navies in the 19th century. Whether or not they originally volunteered for duty, sailors frequently slipped off ships in port seeking better conditions or higher pay. A common language made United States ships particularly attractive to British deserters. The British navy, which was at war with the French empire, short of sailors, and the dominant force on the high seas, aggressively tried to retake deserters. On meeting an American ship at sea, British naval officers frequently boarded it and inspected the crew on the pretext of seeking deserters. They often made their determination based on the man’s accent, as naturalization papers could be forged. Total estimates vary, but at least 6,000 men were forcibly removed from U.S. ships between 1803 and 1812.

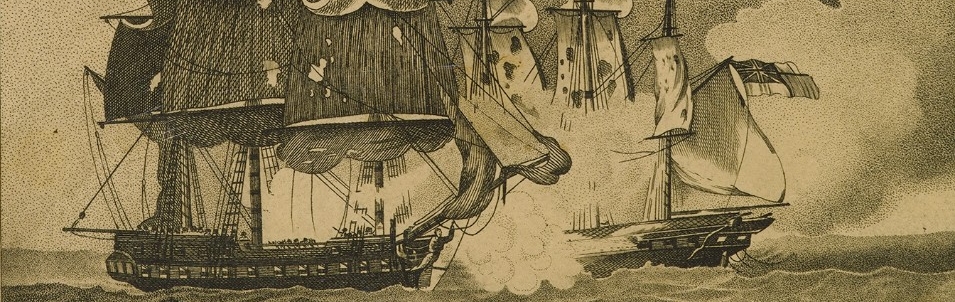

In June 1807, H.M.S. Leopard commanded by Captain Salusbury Humphreys stopped U.S.S. Chesapeake as it departed the Chesapeake Bay, demanding to search for deserters from H.M.S. Melampus, which had recently resupplied at Hampton Roads, Virginia. Chesapeake’s Captain James Barron refused and his ship was fired upon by Leopard. Unprepared for action, Chesapeake surrendered and a British party boarding party removed four alleged deserters before assisting the American ship in returning to Hampton Roads. News of the insult to a United States Navy warship caused public outrage and President Thomas Jefferson expelled British ships from American ports and waters.

In the spring of 1811, John Rodgers, the commander of the squadron protecting the northeast U.S. coast, received word that British and French ships were interrupting trade off New York. After putting to sea on 14 May, Rodgers in his flagship U.S.S. President encountered H.M.S. Little Belt in that area. Both captains denied firing the first shot, but that night the two exchanged fire for about fifteen minutes, killing 9 on board Little Belt. For the British public, it was an insult as great as the Leopard versus Chesapeake incident had been to the American public.