Hawaiian Islands

Their present work completed, Porpoise and Flying Fish joined the other ships at Mathauata and related the sad news. Wilkes then dispatched the squadron on various final tasks, after the completion of which they all rejoined at the same place. Wilkes then made assignments for the next leg of the voyage, which would end with a rendezvous at Honolulu in the Sandwich Islands. The squadron departed the Fiji Islands on 11 August.

The stop in the Hawaiian, or Sandwich, Islands was a welcome one. The islands had a far more advanced civilization, in western terms, than the other Pacific islands, and had more experience in welcoming foreign ships, though foreign customs, habits, and diseases were taking their toll on the morals and health of the local population. They had been united under a monarch for twenty years, and within days of the squadron's arrival, the king's government completed instituting a constitution. A colony of British, French, and American settlers centered on Honolulu, but there were missionary outposts throughout the archipelago.

King Kamehamea III had left instructions with his officials that he should be sent for at Maui as soon as the expedition arrived. He arrived at Oahu on 29 September and made a formal welcome. Three days later the king informally sent for Wilkes and the two spent three hours discussing the history and political affairs of the islands, of which both Great Britain and France were seeking domination. The king also assisted the expedition's scientific mission by allowing the use of his palace at Honolulu as the site for the temporary observatory, instrument repair shops, and workrooms for the calculation and drawing of charts. He also sent word to his officials on the other islands to provide assistance to the explorers.

The ships underwent repairs immediately upon arrival, and Wilkes allowed the officers and scientifics to take quarters ashore in order to give them better access to their assigned tasks. The officers assisted with the preparing the charts while the scientifics assembled many of their findings and collections to that date and sent them back to the United States. They also began exploring Oahu. Flying Fish was soon ready, so Wilkes sent it off with the scientifics on board to survey the other islands. Alfred Agate accompanied a two week excursion to Kauai where he teamed with James Dana to observe geology, land formations, and "scenery." Sites visited included Waimea and Hanapepe. Agate then remained at Honolulu while some of the scientists visited the island of Hawaii.

On Flying Fish's return from island of Hawaii, Wilkes issued orders for it and Peacock to survey islands in the western end of the Pacific whaling grounds. Additional orders sent them back to Samoa to correct some of the surveys made by Porpoise, which Wilkes considered incomplete. He also gave Captain Hudson a list of hostile acts and "rascals" that he wanted him to investigate and, if necessary, punish. First among these was an order to make another attempt to capture Chief Opotuno at Savaii Island, Samoa. Again, Wilkes assigned more tasks than could possibly accomplished in the allotted time. Hudson was to bring the ships to meet the others at the Columbia River no later than 1 May 1840. As members of the ship's complement, the scientifics assigned to these ships, which included Alfred Agate, also accompanied the excursion. They left Hawaii on 2 December.

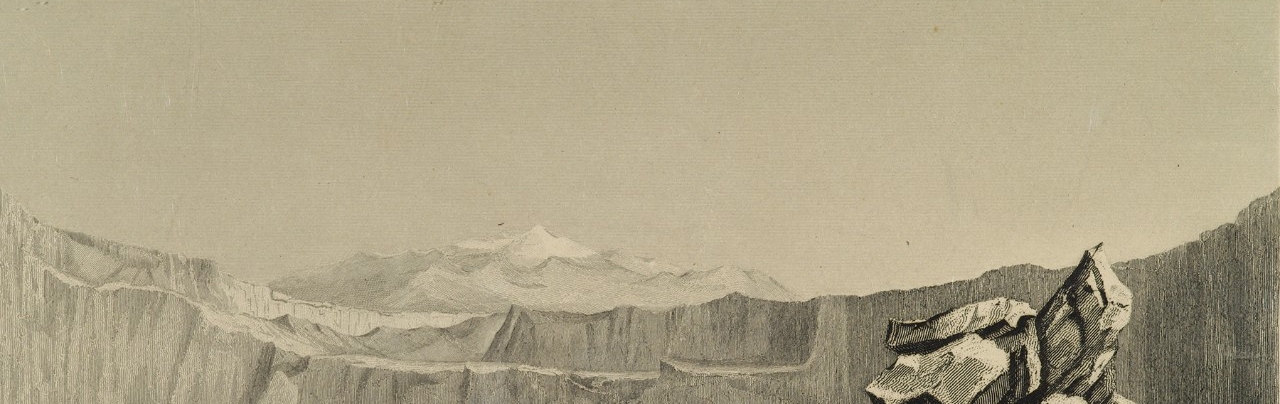

Vincennes departed the next day for the island of Hawaii and an expedition to the top of Mauna Loa. Along the way to the summit, they encountered one of Mauna Loa's lower volcanic craters, Kilauea. Purser R. R. Waldron and Joseph Drayton ventured inside the crater and walked on the dome's hot surface until lava oozed through cracks that formed within fifteen feet of them. Wilkes' dog Sydney accompanied them down and scorched his paws on the surface. The train then continued on for the summit. The party swelled to over three hundred with more than two hundred hired porters and the family members who insisted on accompanying them, and food and water supplies soon ran critically low. The guides they brought were not as familiar with the territory as they purported and did not know where water supplies lay. Soon a supply party Wilkes sent back returned with two other guides who knew the area well, one of whom was Keaweehu. He told Wilkes that the path his original guides had chosen was not near regular water supplies and that the nearest regular source was ten miles distant. Wilkes had hoped to encounter snow at a higher elevation to solve the problem, but Keaweehu told him that sufficient snow on the mountain was not to be depended upon. Because of the shortage, and because many of the porters were lightly dressed and the temperature was falling as they ascended, and some were beginning to suffer from altitude sickness, Wilkes established a base camp at about 9000 feet and took forward only enough men and provisions to reach the summit. As he neared it, they were caught in high winds and snow, though the snow never supplied ample water. Wilkes spent three weeks, including Christmas, at the summit surveying its volcanic crater, Moku-a-Weo-Weo, and making geologic and meteorologic observations. Finally, on 13 January 1841 they broke camp at the summit and returned to the sea, stopping to study the Kilauea crater and others as they descended.