Setting the Record Straight: The Loss of USS Indianapolis and the Question of Clarence Donnor

By Richard Hulver, Ph.D., and Sara Vladic

This is an original paper written by Dr. Richard Hulver and Ms. Sara Vladic. U.S. Naval Institute published a later version in Proceedings Today.

________________________________

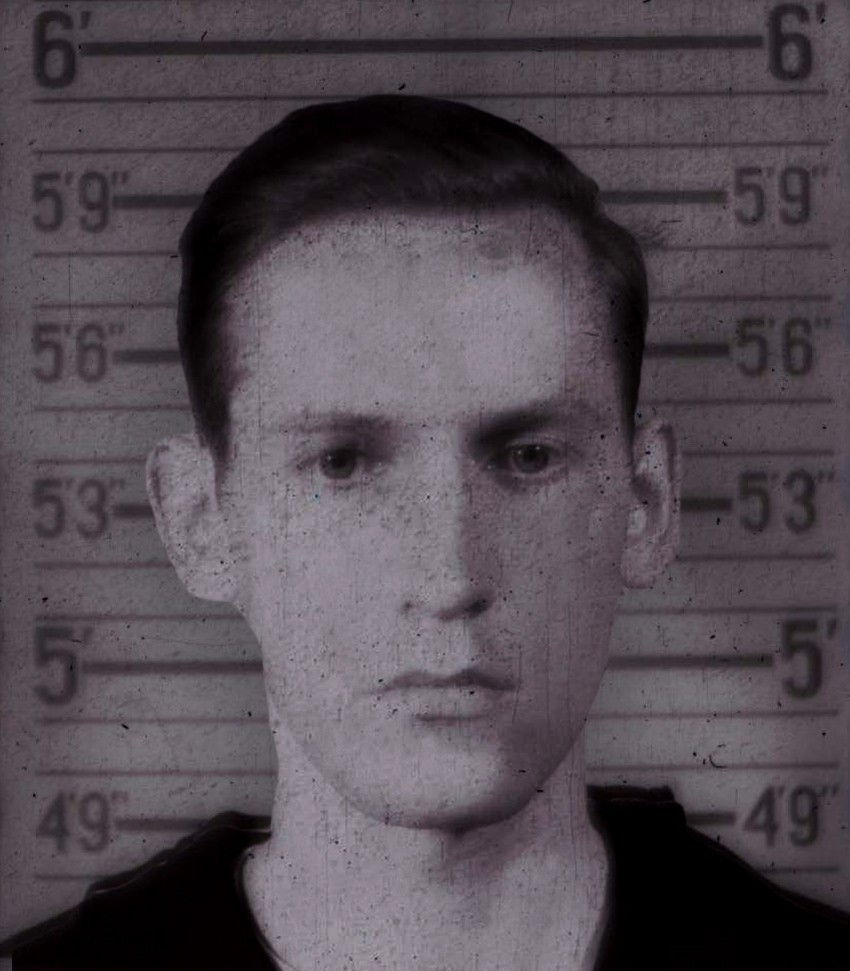

On 12 August 1945, Charles and Ruth Donnor received the worst news a parent can receive. A Navy telegram arrived at their home in Big Rapids, Michigan, informing them that their son, Clarence William Donnor, Radio Technician Second Class, USNR, had been missing in action since 30 July 1945.[1] No further information was given, but they were told that more would follow. As World War II was still ongoing, they were asked to not speak about this news due to the risk of divulging information to the enemy. The news became even more confounding over the following days when they learned that Clarence was feared lost on the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis (CA-35).

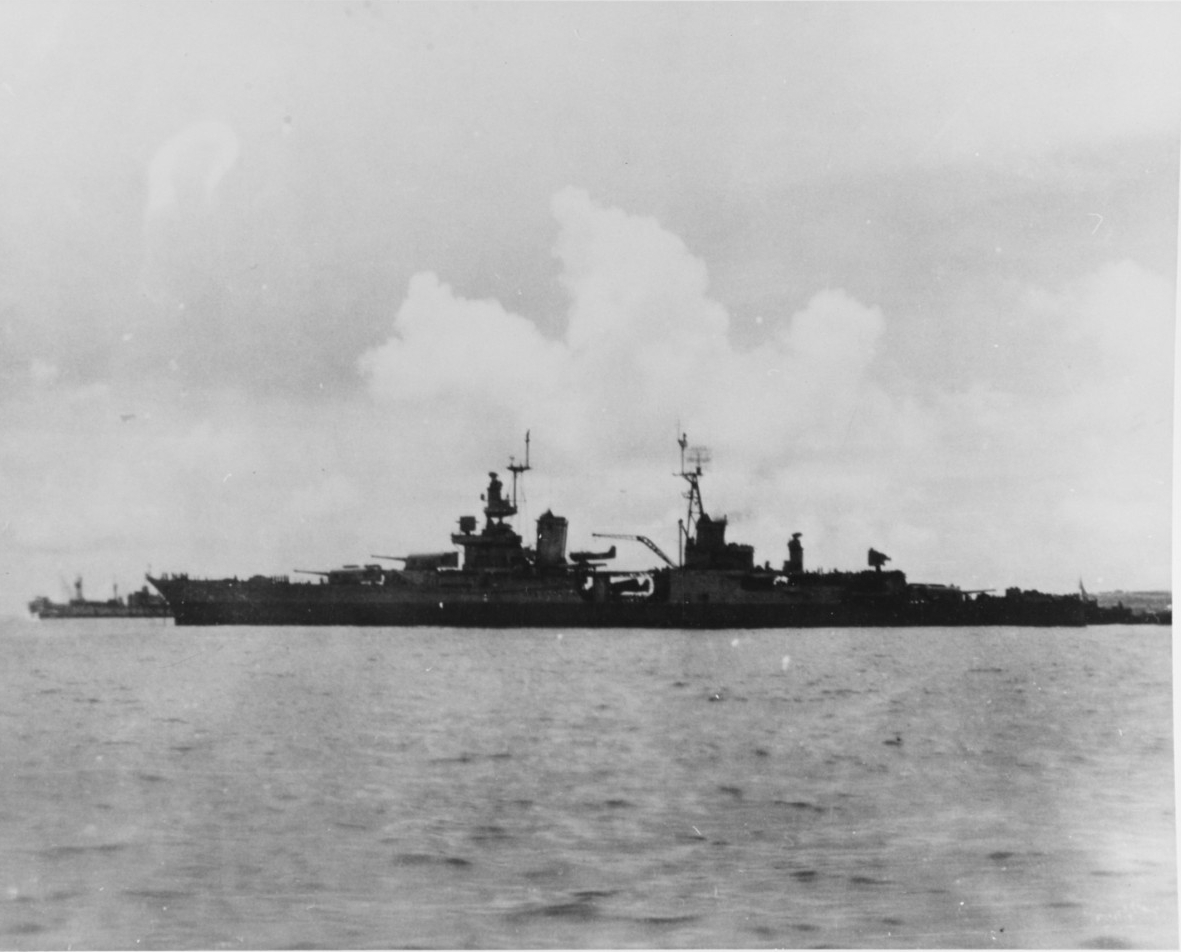

Indianapolis, frequent flagship of the U.S. Fifth Fleet, sank on 30 July 1945 in the middle of the Philippine Sea after being struck by a pair of Japanese torpedoes. Two long-standing mysteries surrounding the loss were the true number of men who sailed on the ship’s final voyage and how many of them survived her sinking. Competing sets of numbers arose: one set from the Navy’s original 1945 tabulations and another from the USS Indianapolis Survivors Organization. Between the fall of 2017 and the spring of 2018, Sara Vladic, an Indianapolis historian and filmmaker, and Dr. Richard Hulver, a historian at the Naval History and Heritage Command with subject matter expertise on the loss of Indianapolis, sorted through hundreds of documents and cross-checked nearly 1,200 names countless times in an effort to rectify the different totals. Their research unearthed a record-keeping error that, nearly three-quarters of a century later, explained what the Donnors had known when they received that Navy telegram in 1945. Their son Clarence was alive, well, and had never sailed with Indianapolis.

Clarence had been listed on Indianapolis’s final sailing list as a passenger, but as various other lists appeared over the years the passenger distinction vanished. On the final sailing list, now in the custody of the National Archives, he was shown as lost at sea. That same list also tallied the total number of survivors as 316. However, in several books, including a book published by the Indianapolis Survivors Organization, Only 317 Survived, he was listed as a survivor. After searching available public records to verify the 317 number, Vladic discovered that Donnor was not lost on Indianapolis. Instead, according to the muster roll of the ocean tug, USS Chimariko (ATF-154), Donner’s Navy career continued until the summer of 1946. While this new research clearly showed that Donnor had lived and not died, it raised two complementary questions: 1.) How had the Navy overlooked a survivor of one of the most publicized disasters in its history? 2.) If the Navy had not overlooked Clarence Donnor, was he actually on Indianapolis when she went down?[2]

To answer these questions, Curator of the Navy and Director of Naval History and Heritage Command, Rear Admiral Samuel Cox, USN (Ret.), asked Dr. Hulver to lead a deep dive into this long-standing question. The NHHC team obtained the complete personnel record for Clarence Donnor from the National Archives’ National Personnel Records Center and found the answer to the decades-long discrepancy.

When the Japanese submarine I-58 hit her with two torpedoes, Indianapolis sank within 12 to 15 minutes, and all paper records went down with the ship. Among the lost documents was the detailed crew roster, including documentation of any changes in the crew that took place between 16 July and 28 July 1945 during transits from San Francisco to Pearl Harbor, Pearl Harbor to Tinian, Tinian to Guam, and finally Guam to Leyte.[3] At the conclusion of rescue operations on 3 August, the Navy hurried to reconstruct the ship’s final sailing list and account for the missing. Seven different lists were compiled to verify crew and survivors. These lists differentiated between officers and enlisted, sailors and Marines, regular crew and special details, and included rosters of all survivors convalescing at two Navy hospitals. The final tabulation and collation of all these lists were included in a memorandum and signed off by Indianapolis skipper, Captain Charles B. McVay III, on 8 August 1945. That list showed 316 men as survivors of the 1,196 personnel on board at the time of the sinking.[4] These lists and the cover memo collectively show the genesis of the Donnor question, provide the final list of survivors, and ultimately establish the correct number of survivors—316 men. The same documents, however, incorrectly identify the total number on board and the total number killed in the tragedy.

Key among the historic lists were rosters from the two hospitals where Indianapolis survivors were taken, Fleet Hospital #114 at Samar and Base Hospital #20 at Peleliu.[5] There is no record of any survivor coming from the water and not requiring hospitalization. Dr. Hulver, therefore, determined that lists from the two Navy hospitals to which the survivors were taken represented a complete tally of survivors. After cross-checking these lists with rescue ship records and accounting for the four individuals who died shortly after rescue, the final accounting shows 149 patients receiving treatment at Hospital #114, and 167 survivors at Hospital #20, totaling 316 survivors. All discrepancies in the lists can be accounted for by cross-checking the hospital rosters, sailing list, deck logs for the rescue ship, USS Bassett (APD-73), and the Survivors Organization list—except for Donnor. Dr. Hulver’s conclusions, peer reviewed by several NHHC historians, were shared with Sara Vladic who did an additional review and reached the same conclusion.

A Navy casualty card with a category of “missing” from Indianapolis was filled out for passenger Clarence Donnor on 11 August when he failed to materialize among survivors at either hospital. The Navy telegram to his parents informing them of the horrible news was sent on 12 August. The very next day, Clarence’s mother, Ruth, typed a letter to Chief of Naval Personnel Vice Admiral Randall Jacobs: “We are pleased to inform you that we have talked with our son since that date [when he was declared missing on 30 July] and also had a postal card and letter. He is now en route to a naval school in New York.”[6] Mrs. Donnor went on to explain that she thought the mistake was made because of a change in Clarence’s plans at Shoemaker, California. RT2c Donnor was “taken to Treasure Island [California] and from there ferried to the Cruiser Indianapolis to be a passenger to some island base in the Pacific. He had been on the ship but a half hour when the call came through for him to take his gear and go back to Shoemaker.”[7] She was happy to report to VADM Jacobs that her son was “safe and well” and hoped her letter would “help to keep your records straight.”[8] It did so imperfectly. The Navy immediately launched an investigation to verify Mrs. Donnor’s claim and, on 23 August, the original casualty card for her son was amended from “missing” to “survivor,” the change coded with an infrequently used number indicating that it was made due to family correspondence.[9] Commander H.B. Atkinson, the officer in charge of the Bureau of Naval Personnel (BUPERS) Casualty Section was “pleased to confirm [with Mrs. Donnor] the information contained in your letter of 13 August 1945 concerning the welfare of your son.”[10] “Any anxiety you may have been caused by the telegram stating that your son was missing is deeply regretted,” he wrote.[11]

Donnor’s file indicates that within hours of arriving on Indianapolis, his notice of acceptance into an officer training program arrived with orders to report to Fort Schuyler, New York. His deployment to the Pacific was canceled. As Donnor began planning to make his way across the United States, the crew of Indianapolis finalized preparations for their fateful voyage back to war. [12] Within a day of his departure, components for the atomic bomb Little Boy were loaded onto Indianapolis, and she departed with her top-secret cargo the morning of 16 July. Amid the chaos of the ship’s hurried redeployment, Donnor’s arrival onboard was apparently recorded, but his hasty departure overlooked. Thus, when the paper records were reconstructed, he remained on the final crew list resulting in a complement of 1,196—one man too many.

While the Navy almost immediately knew that Donnor had lived, the initial clerical error remained in the historic Navy lists with no explanation, and what became the official numbers were partially flawed. Knowledge of Donnor’s survival crept into updated lists as early as 1963.[13] Sources that began including Donnor as a survivor of the ordeal indicated that he was rescued by Bassett.[14] If correct, this meant that he must have traveled to Hospital #114, which had no record of his admittance.

Sara Vladic’s research into the personal stories of the survivors buttresses the evidence from Donnor’s personnel file. Over the past 17 years, she has met with and interviewed more than 107 survivors, collecting the memories of nearly all crew still available for interview. She also interviewed members of the various rescue crews. When all the survivors were at last gathered in one place, at Base Hospital #18, Guam, they came to understand the scope of what they had endured. Desperate to know the fate of their friends, they sought out and created crew lists, compared notes with their buddies and division members, and tried to account for all the men on the ship. It stands to reason that had Clarence Donnor been aboard the ship, he would have made some connections among the crew, especially with radiomen and radio technicians, 11 of whom were among the survivors. Yet, in nearly two decades of discussions and 170 hours of taped conversations, Clarence Donnor was not mentioned in any of Vladic’s volumes of research—neither as a lost-at-sea crewmember, nor as a survivor. What does strongly come through from the collected memories of survivors, many who have since passed, is the overwhelming sentiment that their survival was nothing short of a miracle.

To an outside observer, this small casualty discrepancy might seem insignificant. To survivors, descendants, friends, and the Navy, it is not. As historians and friends of the USS Indianapolis family, we are committed to commemorating the sacrifices of those who served by accurately telling their story—the good and the bad. We do so by holding ourselves to the highest scholarly standards. This entire event shows the inherent difficulties in accounting for casualties in the fog of war and in verifying those figures years after the fact—particularly with an episode as chaotic as the loss of Indianapolis. We can now confirm, 73 years later, that the Navy’s number of survivors in 1945 was correct at 316, and that the final crew list for that tragic voyage has been corrected to show 1,195 men were on board and 879 lives lost.

Thank you, Mrs. Ruth Donnor, for helping to keep our records straight.

DR. RICHARD HULVER is a historian at the Naval History and Heritage Command. He has previously worked as a historian for United States Southern Command, the American Battle Monuments Commission, and the U.S. Army Chief of Staff’s Iraq War Study Group. He has written extensively on U.S. WWI and WWII military commemorations. He is the subject matter expert on USS Indianapolis at NHHC and is the author of the forthcoming documentary history covering the loss of the ship, A Grave Misfortune: The USS Indianapolis Tragedy (GPO, 2018).

SARA VLADIC is an award-winning documentary filmmaker and has appeared as a subject matter expert for National Geographic and the Smithsonian Channel. She is coauthor, with Lynn Vincent, of INDIANAPOLIS: The True Story of the Worst Sea Disaster in U.S. Naval History and the Fifty-Year Fight to Exonerate an Innocent Man (Simon and Schuster, July 2018).

[1] “Telegram from Chief of Naval Personnel to Mr. and Mrs. Donnor,” 12 August 1945, Navy Personnel File of Clarence William Donnor, NARA, St. Louis, Missouri.

[2] In the U.S. Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936–2007, Clarence Donnor’s death date is listed as February 1, 2002. His birthday and names of his parents also match the information for this social security number.

[3] Despite its top-secret delivery mission, Indianapolis carried a large number of passengers from the transit stateside to the Pacific Theater. Many passengers offloaded at Pearl Harbor and likely at the other stops on the voyage. Clarence Donnor’s listing as a “passenger” on an early list makes the information in these lost records all the more important.

[4] The original total for the number on board was 1,198. McVay scratched through this, wrote 1,196 and initialed it. It is not known on what date McVay’s edit to the 8 August document took place. McVay also changed the number of officers onboard from 84 to 82, the number of officers missing from 69 to 67, and the total number of missing from 878 to 876 [with 4 additional confirmed dead listed, bringing the total lost to 880]. He made no corrections to the survivor figures.

[5] The only ship to take survivors to Hospital #114 in Samar was Bassett (APD-73) All other men pulled from the water were taken to the closer hospital, #20 at Peleliu by Cecil J. Doyle (DE-368), Ringness (APD-100), and Register (APD-92). See Peter Wren, Those in Peril on the Sea: USS Bassett Rescues 152 Survivors of the USS Indianapolis (Richmond, Virginia, 1999).

[6] Mrs. Ruth Donnor to VADM Randall Jacobs, Chief of Naval Personnel,” 13 August 1945, Navy Personnel File of Clarence William Donnor, NARA, St. Louis, Missouri.

[9] See “Reports of Casualty,” 23 August 1945, in Navy Personnel File of Clarence William Donnor, NARA, St. Louis, Missouri. The coding of this change is important to note because in the final IBM WWII casualty tabulations, Clarence Donnor’s name is struck through with casualty explanatory code “6902,” which is not listed among the codes in the key for this list. There is an explanatory note on one of the pages in Donnor’s personnel file that 6902 means that a special letter was submitted by next-of-kin.

[10] H.B. Atkinson to Mrs. Charles Donnor,” 24 August 1945, Navy Personnel File of Clarence William Donnor, NARA, St. Louis, Missouri.

[12] “Orders from Commander U.S. Naval Training and Distribution Center Shoemaker, California, to Commanding Officer Receiving Station, Navy 128,” 29 July 1945/31 July 1945, Navy Personnel File of Clarence William Donnor, NARA, St. Louis, Missouri.

[13] Thomas Helm, Ordeal by Sea: The Tragedy of the U.S.S. Indianapolis (New York, New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1963) includes Donnor on the roster as “wounded” in his book. Donnor is not listed among the survivors in a book that precedes Helm’s, Richard Newcomb, Abandon Ship: The Saga of the U.S.S. Indianapolis, the Navy’s Greatest Disaster (New York, New York: Harper Collins, 1958).