Civil War Naval Operations and Engagements:

Port Royal

South Carolina

7 November 1861

Federal Leadership:

Flag Officer Samuel Francis “Frank” Du Pont, United States Navy (USN)

Brigadier General Thomas W. Sherman, United States Army (USA)

Confederate Leadership:

Captain Josiah Tattnall, Confederate States Navy (CSN)

General Thomas Drayton, Confederate States Army (CSA)

BACKGROUND

On 19 April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln called for a blockade of Confederate ports along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. In May 1861, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles convened a Commission of Conference, or Blockade Strategy Board. The purpose of the board was to take on the enormous task of devising a strategy for maintaining an effective blockade of 3,500 miles (5,600 km) of coastline. The board members included Captain Samuel Francis Du Pont, Captain Charles H. Davis, both of the U.S. Navy; Major John G. Barnard, of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; and Professor Alexander D. Bache, of the Coast Survey. These men authored a series of reports during their meetings at the Smithsonian Institution from July to September 1861. Among their recommendations, they proposed a series of attacks designed to create safe harbors further along the southern coastline. They also recommended the division of the Atlantic squadron at the border of the Carolinas. [1]

Secretary Welles subsequently selected the board’s chairman, Captain Du Pont, as the leader of the new South Atlantic Squadron. Promoted to Flag Officer, Du Pont led a great expedition to establish a base at the Port Royal Sound in South Carolina in the fall of 1861. Brigadier General Thomas W. Sherman, U.S. Army, accompanied Du Pont on his expedition in command of the 12,000 men assigned to the anticipated amphibious operation. Welles purposely left the final decision upon which of the suggested targets to occupy to him.

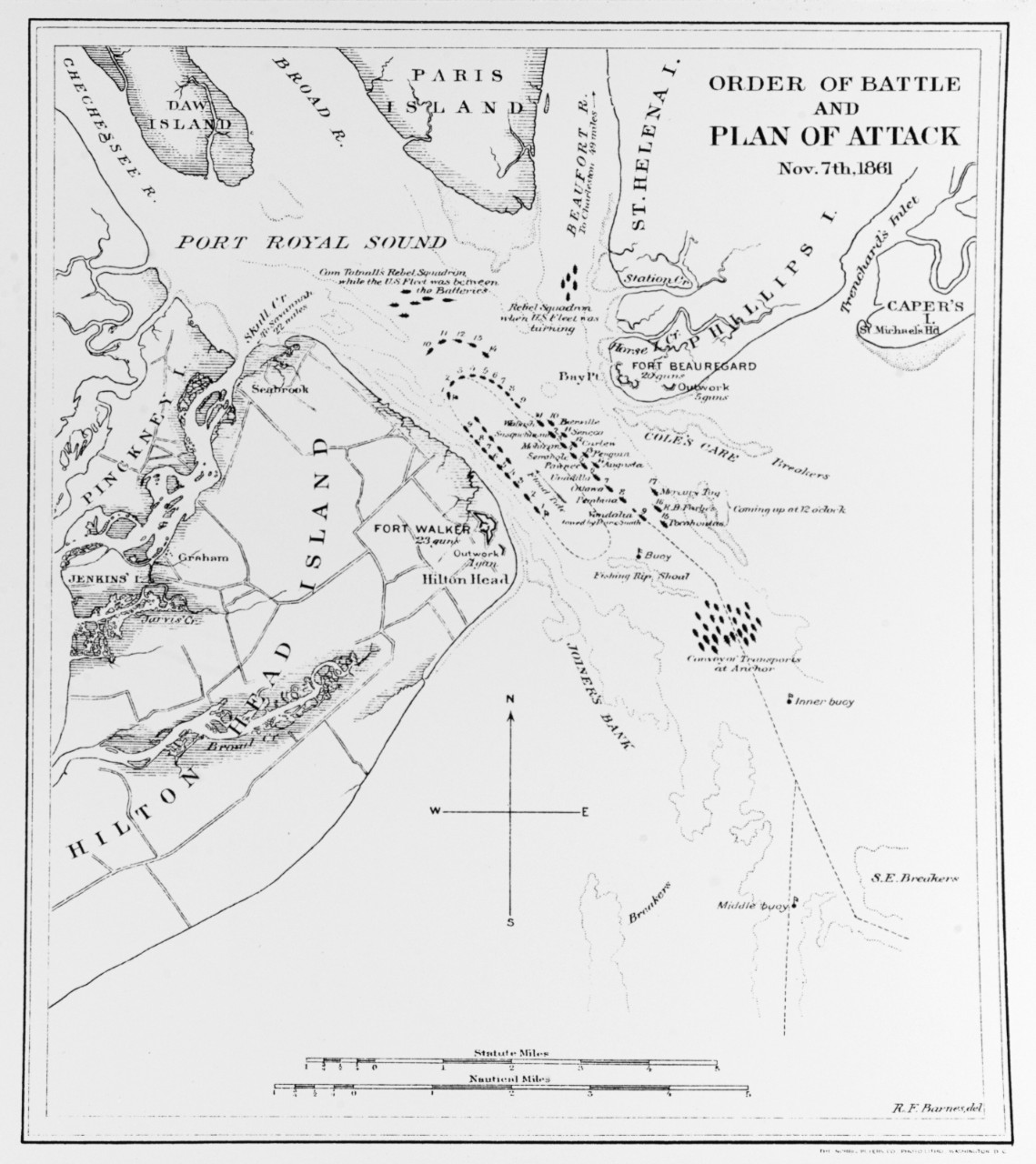

In July 1861, Confederate Major Francis D. Lee, of the South Carolina Army Engineers, began building the forts made of palmetto logs and dirt at the entrance to Port Royal Sound. They named the fort at Hilton Head in honor of the first Confederate Secretary of War, Leroy P. Walker, and the battery on Bay Point in honor of General P.G.T. Beauregard.[2] Fort Walker was garrisoned by 1,450 men of the 11th Regiment, South Carolina Volunteers, commanded by Colonel William C. Heyward. Colonel R. G. M. Dunovant commanded Fort Beauregard with 640 men under his command. Neither fort was complete when they received word that they were the intended target of Du Pont’s expedition in November.

PRELUDE

On 28 October 1861, Commander Francis S. Haggerty, of Vandalia, led a supply convoy of 25 vessels south from Hampton Roads. No captain except Haggerty had knowledge of their destination. Each held a sealed envelope to open only if the convoy separated during their journey. The fast ships followed the supply convoy a day later led by the flagship Wabash. The secrecy of the destination of this expedition extended to all the officers in command of vessels in the fleet. In spite of these measures, Confederate Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin learned of the destination of Du Pont’s expedition, and he quickly spread the word. [3]

A storm off the coast of Cape Hatteras threatened to disperse the fleet. Other than the gunboats and regular Navy vessels, most of the vessels in this convoy were not built for an ocean voyage, especially the ferryboats that were being used as transports for the Army. The next day, Du Pont had sight of only one gunboat from his flagship. The next day, the ships began to re-appear, having opened their secret orders. Two transports, Governor and Peerless, sank in the storm; other ships of the fleet were able to rescue those aboard the sinking ships with the exception of seven Marines who drowned. Isaac Smith had thrown all except one of her guns overboard to avoid sinking in the storm. The steamer Belvidere returned to Fortress Monroe. Union and Osceola were missing. [4] The storm caused the delay of another transport, Ocean Express. General Sherman felt frustrated by the loss of ammunition and landing boats, and therefore he was reluctant to engage his remaining forces in an amphibious landing as they originally planned for Port Royal. [5]

Passing the port of Charleston, Du Pont sent Lieutenant Daniel Ammen, in command of Seneca, to collect Susquehanna and other vessels in port. The Confederate batteries fired upon Seneca when entering the harbor although they knew their city was not the target for this expeditionary force. Brigadier General Thomas F. Drayton, Confederate States Army (C.S.A.), in command of the overall defense of Port Royal Sound, knew what was coming. [6] His reinforcements were in route to Fort Walker when the U.S. Navy ships passed Charleston. [7]

On the morning of 4 November, Wabash and twenty-five vessels of the U.S. Navy arrived near Port Royal. Flag Officer Du Pont sent Commander Davis and Mr. Charles Boutelle of the Coast Survey, aboard Vixen, to determine how to navigate the channels and put out buoys. A channel for the ships with a draft of less than 18 feet was determined before noon. It proved more difficult to find a channel deep enough for Wabash. Lieutenant Thomas H. Stevens aboard Ottawa led a division of light-draught gunboats forward while they waited for the flagship. Commodore Josiah Tattnall, formerly of the U.S. Navy, challenged them with his mosquito fleet of two or three converted tugboats led by his flagship, the Confederate steamer Savannah.[8] He hoped to delay their operations until reinforcements arrived at the forts.[9] Ottawa, Seneca, Curlew, Pawnee, and Isaac Smith proceeded to returned fire. Forced to retreat quickly, Tattnall repeated this exercise on the following day with the same purpose. The reinforcements arrived at Fort Walker on the same day.[10]

On the following morning, the flagship, Wabash, was able to cross the bar and anchor within five miles of the forts, accompanied by Susquehanna and the heavy army transports.[11] Unfortunately, in their hurry to get closer, the flagship ran aground on a shoal and it was too late to press their attack. The squadron laid anchor for the night out of range of the enemy batteries.[12] The weather on the following day forced Du Pont to wait another day. As they waited, Lieutenant Roswell Lamson, aboard Wabash, wrote, “if I fall I only hope it will be said, He did his duty and fell like an American Sailor.”[13] The next day, Lamson commanded the ship’s forward swivel gun during the attack on Fort Walker.

BATTLE

On the morning of the 7 November 1861, General Thomas F. Drayton, CSA, watched the enemy approach from his plantation on Hilton Head near Fort Walker. He later wrote, “not a ripple upon the broad expanse of water to disturb the accuracy of fire from the broad decks of that magnificent armada about advancing, in battle array, to vomit forth its iron hail, with all the spiteful enemy of long-suppressed rage and conscious strength.”[14] No more waiting, the battle began in earnest.

In preparing his attack, Du Pont focused his attention on Fort Walker after assessing the caliber and range of the enemy’s guns. Fort Walker had more guns and those mounted facing seaward were larger in caliber and greater range than Fort Beauregard. The two forts were a little over two miles apart. There was no advantage to engaging them simultaneously as the range of their guns did not allow them to reach the middle of the entrance to the sound.

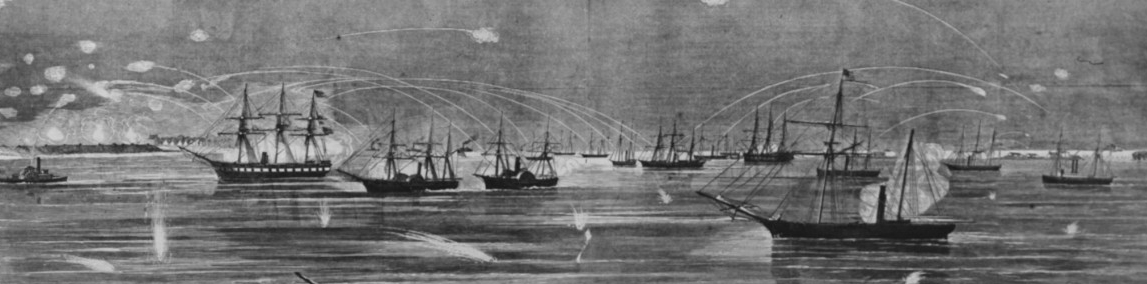

Du Pont’s squadron included 11 regular gunboats and six armed merchant vessels, altogether approximately 151 guns. Du Pont hoped to nullify the advantage of a fixed coastal fortification over attacking ships. He planned to build on this immense shipboard armament by taking advantage of steam power. During his attack, he instructed his captains to keep the ships moving rather the traditional approach to anchor and fire from a stationary position.

Du Pont planned a two column assault during which one column guarded the Beaufort river entrance on the northern end of the harbor against Confederate gunboats. The other column passed between the forts and circled around behind Fort Walker to bombard its weakest front. Their elliptical movement with each pass constantly changing their distance from the forts made the ships even more difficult targets.[15] Isaac M. Smith towed Vandalia, a wooden sailing vessel, to make use of its cannons. After the first turn, Mohican and several other ships dropped off their column and executed enfilading fire upon the fort.[16] Luckily, this deviation from the original plan did not hamper the effectiveness of the ships that continued to circle past the fort. [17] Delayed by the storm, Captain Percival Drayton, in command of Pocahontas, arrived late with Mercury and R.B. Forbes, but all three ships quickly joined the bombardment in progress.[18]

After four hours of engagement and three turns of Wabash, the garrison of Fort Walker abandoned their post.[19] With no visible damage returned upon the attacking fleet, General Drayton, CSA, believed it was more prudent to evacuate the fort before they had no escape. General Robert E. Lee, CSA, arrived further inland in time to witness the Confederate retreat from the batteries toward Bluffton via Ferry Point.[20] The Confederate troops quietly abandoned the island of Hilton Head while the Union gunboats continued to fire upon the empty fort. At 2:45 in the afternoon, Du Pont signaled the cease-fire. Commander C.R.P. Rodgers confirmed the garrison had abandoned Fort Walker.[21] Before sunset, Union soldiers had occupied both Fort Walker and Fort Beauregard. This victory enabled General Sherman's troops to occupy Port Royal and protect it as the base of operations for the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron.

AFTERMATH

“It is not my temper to rejoice over fallen foes, but this must be a gloomy night in Charleston. I shall soon stop all connection between it and Savannah by the inland sounds. This is a far better harbor than either and will enable us to command both in the blockade.”

Captain Samuel F. Du Pont, to his wife, Sophie, November 1861

With the occupation of Port Royal, Du Pont engaged in a campaign that strictly followed the plan established by himself and the rest of the blockade strategy board. He was able to quickly establish a base of operations to reinforce the Union blockade of the Confederate-held cities of Charleston, South Carolina, and Savannah, Georgia. The marshes around Port Royal offered protection against any attempt by the enemy to retake the island.

After the battle, General Sherman led his troops ashore to take command of both forts. Although the joint amphibious operation that had been part of the original battle plan never happened, Du Pont continued to seek out opportunities for joint operationn. However, Du Pont became increasingly frustrated with repeated failures of communication. In the coming months and year of this war, Du Pont often made the decision to go it alone, as he had at Port Royal.

The Confederate strategy for coastal defense changed drastically after the battle of Port Royal. On 5 November, Jefferson Davis had created a new military department that encompassed the coasts of South Carolina, Georgia, and East Florida. He assigned General Robert E. Lee to this new department only a day before the battle of Port Royal. Lee established his new headquarters at Coosawatchie, on the Charleston and Savannah Railroad following their retreat from Port Royal. He began removing from the less important coastal fortifications to avoid spreading their resources too thin due to the superiority of the U.S. Navy.[22] He elected to focus his resources on the defenses of Charleston and Savannah.

This change in strategy was beneficial to the fledging Confederate navy. Following their retreat at Port Royal, the citizens of the new Confederacy blamed their government for providing their navy with the resources that they needed to succeed.[23] One converted steamer and three tugboats should not have been expected to contend against a fleet of gunboats.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

Additional Resources:

Barratt, Peter. “’Hurrah for South Carolina’” Percival Drayton and The Battle of Port Royal.” Civil War Navy – The Magazine (Fall 2020): 4-14.

Browning, Robert M. "Defunct Strategy and Divergent Goals: The Role of the United States Navy along the Eastern Seaboard during the Civil War." Prologue, Vol. 33: 169-180.

Quarstein, John V. “Battle of Port Royal Sound,” 5 November 2020.

Symonds, Craig. “The Navy’s Evolutionary War.” Naval History 25, No. 2 (March 2011).

Further Reading:

Browning, Robert M., Jr. Success Is All That Was Expected: The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron During the Civil War. Dulles, VA: Brassey’s Inc., 2002.

Coker, Mike. The Battle of Port Royal. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2009.

Lamson, Roswell H. Lamson of the Gettysburg The Civil War Letters of Lieutenant Roswell H. Lamson, U. S. Navy. Edited by James M. McPherson and Patricia R. McPherson. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

***

Notes

[1] Robert M. Browning, Jr., “Defunct Strategy and Divergent Goals: The Role of the United States Navy along the Eastern Seaboard during the Civil War,” Prologue Magazine 33, No. 3 (Fall 2001).

[2] Rowland, Lawrence, Alexander Moore, and George C. Rogers, Jr., The History of Beaufort County, South Carolina: 1514-1861 (Charleston: University of South Carolina Press, 1996), 445.

[3] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (hereafter ORA), 128 vols. (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), Series 1, Vol. 6 (1882), 306.

[4] The steamer Osceola was later confirmed as wrecked and its crew taken prisoner by the Confederate forces at North Island, as cited in Richmond Dispatch (VA), 8 Nov 1861; the steamer Union was confirmed as wrecked, cited in Newbern Weekly Progress (NC), 5 Nov 1861.

[5] ORA 1, 6:4.

[6] ORA, 1, 6:306.

[7] ORA, 1, 53(1896):183.

[8] S. F. Du Pont, Flag Officer, to Hon. Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy, 6 Nov. 1961, quoted in Samuel Francis Du Pont, Official Dispatches and Letters of Rear Admiral Du Pont, U.S. Navy (Wilmington: Press of Ferris Bros., Printers, 1883), 51.

[9] Charles C. Jones, The Life and Services of Commodore Josiah Tattnall (Savannah: Morning News Steam Printing House, 1878), 134.

[10] ORA, 1, 53:184.

[11] James Russell Soley, Daniel Ammen, and A. T. Mahan, The Navy in the Civil War, Vol. 2 (Harrisburg, PA: Archive Society, 1992), 19–20.

[12] ORA, 1, 6:8; Ammen, The Navy in the Civil War 2:20.

[13] Roswell Hawks Lamson, Patricia R. McPherson, and James M. McPherson, Lamson of the Gettysburg: the Civil War Letters of Lieutenant Roswell H. Lamson, U.S. Navy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 41.

[14] Ammen, The Navy in the Civil War 2:21.

[15] Craig Symonds, “The Navy’s Evolutionary War,” Naval History 25, no. 2 (Apr 2011): 26–34.

[16] Daniel Ammen, “Du Pont and the Port Royal Expedition” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. 1, Peter Cozzens, ed. (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007), 683.

[17] Kevin J. Weddle, Lincoln’s Tragic Admiral: The Life of Samuel Francis Du Pont (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005), 138.

[18] Ammen, The Navy in the Civil War 2, 26–27.

[19] Du Pont to Welles, 8 Nov 1861, in Du Pont, Official Dispatches and Letters of Rear Admiral Du Pont, 52.

[20] ORA, 1, 6:312.

[21]Ammen, The Navy in the Civil War 2:27.

[22] ORA, 1, 6:327.

[23] Times-Picayune (New Orleans, LA), 19 Nov 1861; Savannah Republican (GA), 18 Nov 1861; U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 30 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894–1922), Series 1, Vol. 12(1901), 295.