Georgia Clark Sadler

(1941–2022)

Georgia Clark was born on 17 February 1941 in Los Angeles, California. In 1954, her family moved to Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, where her father worked for the Arabian American Oil Company. The following year, she started high school at the American Community School in Beirut, Lebanon. In 1958, she was preparing to graduate when her family was evacuated along with other American citizens ahead of the landing of U.S. Marines in response to an appeal from the Lebanese government.1 She received her diploma in the mail.2

Back in the United States, she struggled to apply for colleges while waiting for her transcripts from Lebanon. Clark attended Drury College in Springfield, Missouri, graduating with a bachelor of arts in education and physical education in May 1962.3

Later that summer, she made the decision to join the Navy. In September, she arrived at the Women’s Officer School in Newport, Rhode Island. Clark graduated first in her class of 30 in March 1963.4Lieutenant (j.g.) Clark was first assigned to serve as the assistant barracks officer at Naval Support Facility Anacostia, in Washington, DC. She was subsequently sent to Barbers Point, Hawaii, where she served as the personnel officer and administrative assistant to the fleet air commander. These assignments followed the traditional route for women serving in the Navy in this decade, but her assignment took Clark in a less traditional direction for female naval officers during this period.

From her experience living in Lebanon, Clark had a strong interest in international affairs, but she never expected to be able to pursue this interest during her Navy career. She was surprised when she was selected for the newly created Defense Intelligence School in Washington, DC. She was the only woman in the class. She was subsequently assigned to the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) to analyze the naval capabilities of South Asian countries.5

After receiving her promotion to lieutenant in July 1967,6 Clark realized that she required further education to ensure her continued promotion. While assigned to DIA, she started evening classes at American University. Before she had finished these, she was selected for a full-time, government-sponsored graduate program. Starting in September 1970, Clark studied public administration at University of Washington in Seattle, Washington.7

The same year that Clark started graduate school, Admiral Elmo Zumwalt became the Chief of Naval Operations. As a result of his initiatives to expand opportunities for women in the Navy, the Naval Academy sought out female instructors for the first time.

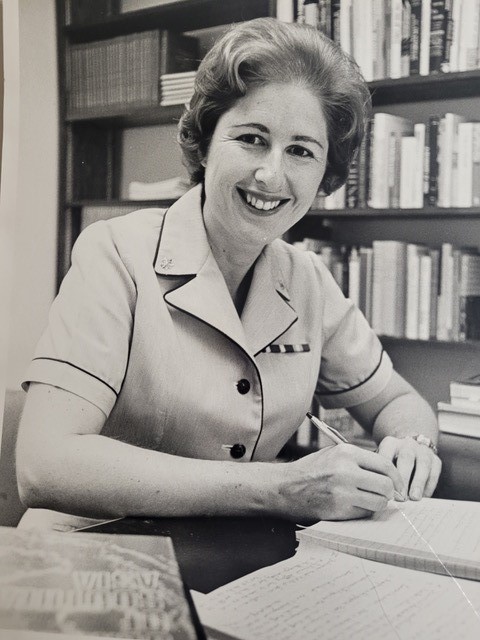

Lt. Cdr. Georgia Clark, while serving as an instructor at the Naval Academy, c. 1972–1975. Image courtesy of Capt. Dudley Sadler.

In 1972, Clark was selected as the first female officer to serve as an instructor at the academy. She taught political science and international relations from 1972 to 1975.8

Following her tour at the academy, Lieutenant Commander Georgia Clark married Captain Dudley Sadler. That same year, she received a new assignment to DIA that marked another first for women in the military. She became the first woman on the morning intelligence briefing team for the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Shortly after her promotion to commander in 1977, Sadler was appointed as a principal action officer in the strategy, plans, and policy directorate (J5) of the Joint Staff. Her knowledge of Southeast Asia made her an ideal candidate for assisting in the Philippine base negotiations, revising the leasing terms for the Clark and Subic Bay bases. She spent two years working on an amendment to the original 1947 agreement.

After an agreement was reached, she accompanied General David C. Jones, chairman of the Joint Staff to the Philippines in March 1979.9 She attended the ceremonies held in honor of the new agreement. Her participation in these negotiations lent her an understanding of this region that she would draw upon later in her career.

Sadler was a lifelong learner, always seeking new opportunities to expand her horizons. During her first tenure with the Joint Staff, she participated in the off-campus seminar program offered by the Naval War College. She graduated in June 1979. A year later, she started a 10-month program at the National War College, which included a trip to the Middle East. The students met with heads of state in Jordan, Israel, and Egypt. This education prepared her for a career focused on national security policy.

At this point, Sadler’s career deviated from international affairs for the first time in over a decade. In the fall of 1980, Sadler was granted her first leadership opportunity. She became the head of the women’s programs section (OP-136E) for the office of CNO.10 She was responsible for monitoring the progress of all programs specifically dealing with women serving in the Navy, including women serving on ships (which had begun in 1978). She was later quoted as saying, “‘Before that, you could never be as good as the men because you had never been to sea.’”11

At the end of her tour at the head of women’s programs, Sadler began writing on behalf of women in the Navy. In a 1983 article in Proceedings, Sadler laid out the issues facing women in the sea services in expressive detail. Although she remained confident that “pragmatism will overcome institutional reluctance,” to accept women in the military, she predicted that “the changes which will occur between 1982 and 1992 probably will not be as dramatic as those which took place between 1972 and 1983.”12 After her time as the head of women’s programs, she continued to advocate for herself and other women in the Navy throughout the rest of her career and into her retirement.

In July 1982, Sadler was assigned back to DIA. She was the first woman to serve as the duty director for intelligence for the Pentagon’s National Military Intelligence Center. She was reassigned 18 months later to the directorate for the Joint Chiefs of Staff support. She was the chief of the Soviet and Warsaw Pact division, in charge of providing senior leadership with current intelligence for this region. Clark was promoted to captain in April 1984.

In August 1985, her experience during the previous Philippine base negotiations prompted her assignment to the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet’s representative in the Philippines. She served overseas for 21 months as an adviser on political-military matters.

Following her overseas tour, Sadler was among ten naval officers selected as a Federal Executive Fellow. She was assigned to the Foreign Service Institute from August 1987 to June 1988, where she participated in the Senior Seminar, a nine-month professional development program for executive training in foreign affairs.

With her level of experience and education, Sadler was next assigned as the director of the East Asia and Pacific branch of the politico-military policy division of the office of the CNO. While in this position, she served on a working group responsible for final round of Philippine base negotiations.13 Within a few months of her appointment to this position, Sadler predicted the loss of the U.S. military bases in the Philippines in an article published in Proceedings.14

During her final tour, Sadler served as a senior officer of a watch section in the Navy’s command center during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. She retired with the rank of captain in August 1991 after 29 years of service.

Her military awards included the Legion of Merit; the Defense Meritorious Service Medal; three Meritorious Service Medals; the Joint Service Commendation Medal; the Joint Meritorious Unit Award; the Navy Unit Commendation; National Defense Service Medal (two awards); and the Navy and Marine Corps Overseas Service Ribbon.

During her retirement, Sadler continued to advocate for women serving in the military, writing numerous articles and book chapters. She served as the director of the Women in the Military Project for the Women's Research and Education Institute. She was a founding member of Alliance for National Defense, a non-profit organization. She also served on the board of directors for the Military Women’s Memorial Foundation. She was a powerful voice for women serving in the U.S. Navy and in the U.S. military, was proud of the progress that has been made, and hopeful for the future.15

Georgia Clark Sadler passed away on 30 November 2022.16

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

Selected List of Works Written by Captain Georgia Clark Sadler

“Women in the Sea Services: 1972–182.” Proceedings 109 (May 1983): 140–55.

“Two Languages in FitReps: . . .” Proceedings 110 (December 1984): 137–39.

“Philippine Bases: Going. Going, Gone?” Proceedings 114 (November 1988): 89–96.

—— and Patricia J. Thomas. “Rock the Cradle, Rock the Boat?” Proceedings 121 (February 1993): 53–54.

“The Polling Data.” Proceedings (February 1993): 52–53.

Women in the Military: Statistical Update. Washington, DC: Women’s Research and Education Institute, 1996.

“From Women’s Service to Servicewomen.” In Gender Camouflage: Women and the U.S. Military. Edited by Francine D’Amico and Laurie Weinstein. New York: New York University Press, 1999.

—— and Tenet, George. “Women’s Assignment to Submarines: An Update.” Alliance Advocate 1, no. 1 (September 1999): 3.

“GAO Study–Occupations: Change is Slow,” Alliance Advocate 1, no. 3 (November 1999): 3.

“Women Warriors: Pragmatism, Politics, and American Society.” In A Century of Service: 100 Years of the Australian Army. Edited by Peter Dennis and Jeffrey Grey. Canberra, A.C.T.: Chief of Army’s Military History Conference, 2001.

Further Reading

Skaine, Rosemarie. Women at War: Gender Issues of Americans in Combat. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1999.

Weinstein, Laurie, and Christie C. White, eds. Wives and Warriors: Women and the Military in the United States and Canada. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey, 1997.

***

Notes

[1] For more information about this operation, see Jack Shulimson, Marines in Lebanon; 1958 (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1966) [PDF].

[2] “Lady Teacher Called ‘Great,’” Springfield Leader and Press (Springfield, MO), 25 June 1972.

[3] Drury University Registrar, email to author, 7 December 2022.

[4] Georgia C. Sadler, “Georgia Sadler Oral History,” Pt. 1, by Robbie Fee, Military Women’s Memorial (also known as Women in Military Service For America Memorial [WIMSA]), 7 April 2011.

[5] “Georgia Sadler Oral History,” Pt. 1, WIMSA.

[6] “Georgia Sadler Oral History,” Pt. 1, WIMSA.

[7] University of Washington Office of Media Relations, e-mail to author, 7 December 2022; Maureen Tubert, “Naval Academy Has Women Instructors Aboard,” Pentagon News, WIMSA, Arlington, Virginia.

[8] H. Michael Gelfand, Sea Change at Annapolis: The United States Naval Academy, 1949–2000 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 117–18. Note that the first female students did not enter the academy until July 1976.

[9] “Georgia Sadler Oral History,” Pt. 1, WIMSA.

[10] Department of Defense Telephone Directory (April 1980), 0-55.

[11] Justin Brown, “A Crack Appears in the Navy’s Brass Ceiling,” Christian Science Monitor, 31 March 2000.

[12] Sadler, “Women in the Sea Services: 1972–82,” Proceedings 109 (May 1983): 140–55.

[13] This agreement was ultimately rejected by the Philippine Senate on 9 Sept 1991. The existing agreement expired on 21 September 1991.

[14] Sadler, “Philippine Bases: Going. Going, Gone?,” Proceedings 114 (Nov. 1988): 89–96.

[15] “Georgia Sadler Oral History,” Pt. 2, WIMSA.