Kalinin Bay (CVE-68)

1943–1946

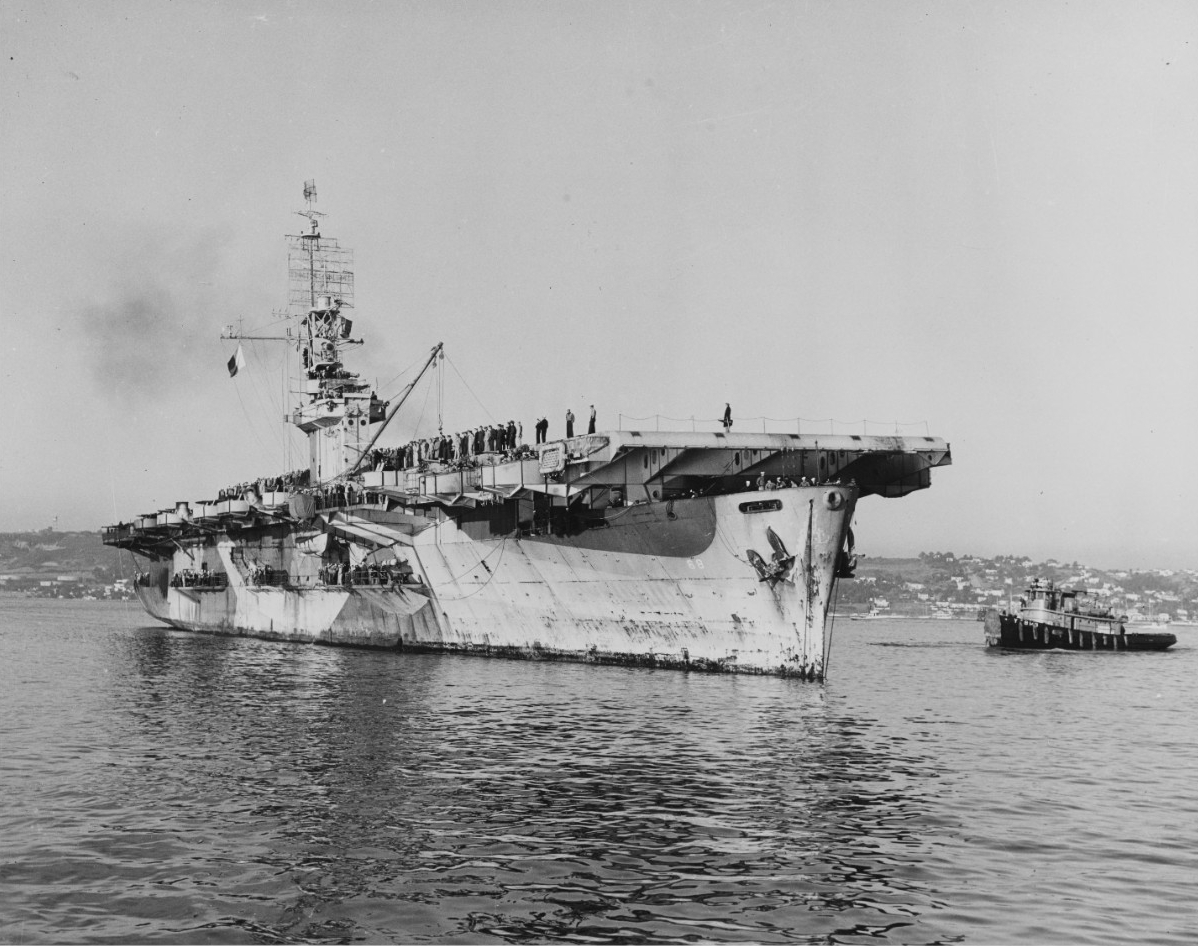

Kalinin Bay (CVE-68) arriving at San Diego, California on 25 November 1944 for repair of damages received in the Battle off Samar a month earlier. Photographed by Naval Air Station San Diego personnel. The ship is painted in Camouflage Measure 33, Design 10A. Official U.S. Navy photograph from the collections of the Naval History and Heritage Command. Catalog#: NH 106571.

A bay on the northern shore of Kruzof Island in the Alexander Archipelago of southeastern Alaska.

(CVE-68: displacement 7,800; length 512'3"; beam 65'; extreme width 101'1"; draft 22'6"; speed 19 knots; complement 860; armament 1 5-inch, 16 40-millimeter, 20 20-millimeter, 28 aircraft; class Casablanca; type S4-S2-BB3)

Aircraft escort vessel (AVG-68) was authorized under a Maritime Commission contract (M.C. Hull 1105); reclassified to an auxiliary aircraft carrier (ACV-68) on 20 August 1942; and laid down on 26 April 1943, at Vancouver, Wash., by Kaiser Shipbuilding Co. Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox approved the name Kalinin Bay for ACV-68 on 4 June 1943; she was reclassified to an escort aircraft carrier (CVE-68) on 15 July 1943; launched on 15 October 1943; sponsored by Mrs. Anna M. Updegraff, mother of Capt. William M. Updegraff; moved down the Columbia River; and commissioned on 27 November 1943, at Naval Air Station (NAS) Astoria, Ore., Capt. Charles R. Brown in command.

Shipyard workers routinely stayed on board the first few hours of an escort aircraft carrier’s commissioning in order to help familiarize the crew with their new systems. The day the ship was commissioned, however, the engineering department manned their stations within scant moments after Lt. Cmdr. James A. Whetton, USNR, the engineering officer, ordered the watch set in the engine room.

Kalinin Bay set out on her shakedown cruise along the Pacific Coast by making a brief voyage to Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Wash. (18–20 December 1943). While there the ship received her allotment of bombs, depth charges, and torpedoes, and she ran the degaussing range, radio direction finder range, and the measured mile. New men continued to arrive to fill out her complement, and two days before Christmas, Vice Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher, Commander, Northwest Sea Frontier, designated the ship Task Unit (TU) 14.5.6.

The exigencies of the war compelled Kalinin Bay and her ship’s company to spend the holidays at sea, and on Christmas Eve the ship thus cleared the harbor, rounded the Olympic Peninsula, and turned southward. The carrier followed the coast until she slipped beneath the Golden Gate Bridge into San Francisco Bay and moored at NAS Alameda, Calif. (23–27 December 1943). More crewmen arrived on board, and the carrier replenished her stock of supplies. The admiral then directed the newly commissioned ship to continue on to San Diego, Calif., which she did (27–30 December). Upon her arrival there, Fletcher dissolved the task unit.

The warship fulfilled what her historian described as “replacement duty” when she embarked 14 officers, 219 enlisted men, and gear and equipment for Marine Air Warning Squadron (AWS) 2. In addition, the ship brought on board 15 North American PBJ-1 Mitchells, 39 officers, and 99 enlisted men of the Air Echelon of Marine Photographic Squadron (VMD) 13. Kalinin Bay turned her prow westward and steamed to Pearl Harbor, T.H. (3–9 January 1944), where the vessel unloaded the marines and their planes and equipment from both squadrons, as well as her own ordnance of aerial bombs, torpedoes, and depth charges.

Kalinin Bay carried out voyage repairs and upkeep, refueled and provisioned, and embarked a mix of USN and USMC aircraft: 31 Grumman F6F Hellcats, 24 Vought F4U-1 Corsairs (with 27 pilots and three enlisted marines), five Curtiss SB2C Helldivers, a dozen Grumman TBF-1 Avengers, and a single Stinson OY-1 Sentinel. The men of Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 422 ferried their Corsairs from Marine Corps Air Station Ewa to Ford Island on 16 January. Escort ship Fair (DE-35) joined the carrier and the two ships formed Task Group (TG) 57.15 and shaped a course for Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands [Kiribati] (18–24 January).

Planners intended for the carrier to approach within 50 miles of Tarawa, the scene of bitter fighting the previous November. The marines would then launch their planes to Hawkins Field on Betio, named in honor of 1st Lt. William D. Hawkins, USMC, who fell storming the island and received the Medal of Honor posthumously. From there the ship was to continue on to a newly won airstrip in the Marshalls. The orders were changed, however, and Kalinin Bay closed Tarawa until she was almost in sight of the atoll on the 24th, and the marines took off in their Corsairs and landed on Hawkins Field on the devastated atoll.

For nearly two weeks, Kalinin Bay provided logistic support from Tarawa to Majuro Atoll in the Marshalls. Fair and Fleming (DE-32) escorted the ship as she rendezvoused with TG 16.10.5, a refueling group that comprised Brackett (DE-41), Stadtfeld (DE-29), and Tisdale (DE-33), along with oiler Lackawanna (AO-40), and refueled (31 January–3 February 1944). During the evolution, Kalinin Bay became the fleet guide, and Capt. Brown acted as the officer in tactical command (OTC). The ship also launched a pair of Hellcats, two Helldivers, and a trio of Avengers, which flew to the flight decks of TG 58.3 as replacements for planes lost in battle and by accidents—aircraft carrier Bunker Hill (CV-17) and small aircraft carriers Cowpens (CVL-25) and Monterey (CVL-26). Those ships, in turn, sent two other Hellcats to Kalinin Bay in the brief flurry of exchanges.

Lackawanna and her screen returned to Majuro, while Kalinin Bay and her escorts rendezvoused with TG 58.1, consisting of battleship Massachusetts (BB-59), Enterprise (CV-6), Yorktown (CV-10), Belleau Wood (CVL-24), light cruiser Oakland (CL-95), and nine destroyers on the 4th. Kalinin Bay sent 16 Hellcats, a single Helldiver, and four Avengers over to those carriers. The busy day was not over as the ship then met TG 58.2, comprising Alabama (BB-60), North Carolina (BB-55), South Dakota (BB-57), Essex (CV-9), Intrepid (CV-11), Cabot (CVL-28), San Diego (CL-53), and ten destroyers. Kalinin Bay launched ten Hellcats and two Avengers as replacements for those carriers, and slipped back into Majuro later that day. Kalinin Bay’s crew increasingly and affectionately referred to their ship as “K.B.”

Kalinin Bay then (6–7 February 1944) steamed to Tarawa, ably escorted by Fair. Upon arrival there, she received 12 F6F-3s of Fighting Squadron (VF) 1, along with 21 officers, two marine officers, and 32 enlisted marines. In addition, the ship loaded 21 USAAF Bell P-39 Airacobras and eight enlisted Army maintainers and swung around for Hawaiian waters. Kalinin Bay touched at Makin Atoll en route on the 10th, and a civilian, two officers, 204 enlisted sailors, 32 enlisted marines, nine Army officers, and 263 enlisted soldiers boarded for the remainder of the passage, and the passengers disembarked when she returned to Pearl Harbor on 17 February. Designated TU 19.9.8, the carrier welcomed another 13 officers, 152 enlisted sailors, and 22 enlisted marines as passengers, and loaded five Consolidated PBY-1 Catalinas, one PBY-5A, seven Lockheed PV-1 Venturas, six Curtiss SO3C Seamews, two Grumman J2F Ducks, and one Curtiss SOC Seagull, and steamed to NAS Alameda (19–24 February).

Composite Squadron (VC) 3, Lt. Cmdr. William E. Keighley, USNR, in command, reported on board on 25 February 1944. The squadron counted 31 officers, 188 enlisted men, eight Eastern FM-2 Wildcats, six Eastern TBM-1 Avengers, and four TBM-1c’s. The Pacific Fleet meanwhile dissolved TU 19.9.8 and the ship became a part of Carrier Division (CarDiv) 24.

Kalinin Bay and hew newly embarked squadron steamed to San Diego and then carried out a series of training exercises in southern Californian waters (26 February–9 March 1944). On the 2nd, StM2c Ernest Johnson, USNR, fell overboard, but despite an extensive search, the ship failed to locate him. Kalinin Bay then (10 March–6 April) completed alterations and repairs at Naval Dry Docks on Terminal Island, near San Pedro, Calif.

The carrier then (7–8 April 1944) returned to San Diego, where she embarked 30 officers, 96 enlisted sailors, 25 marine officers, and 237 enlisted marines, as well as all of the men, a dozen FM-2s, and nine TBM-1c’s of VC-3. Kalinin Bay furthermore loaded on board nine Hellcats and 40 Helldivers for transportation into the war, and the heavily laden ship then (9–15 April) set out for Pearl Harbor, where she disembarked the passengers and unloaded the ferried planes.

The increasingly seasoned ship turned her prow westward on the 17th and became a part of TG 16.6, which also comprised Copahee (CVE-12), together with destroyers Bailey (DD-492) and Capps (DD-550). Capt. Brown once again served as the OTC in Kalinin Bay.

Tragedy struck the ship on 18 April 1944 when she lost two TBM-1c Avengers while they flew an antisubmarine patrol. The wind was 34 knots, the sea moderate, and the planes had 366 feet of allowed flight deck space. The Navy was in the process of introducing the Mk. IV rocket launcher, and maintainers installed the equipment onto some of the torpedo bombers on board. Lt. Walter D. Crockett, USNR, AMM1c Albert E. Aimone, USNR, and AMM2c Asa L. Crew, USNR, of VC-3 flew the first one (BuNo 16811). The plane carried a load of four 5.5-inch rockets installed with the new system, along with two 350-pound depth bombs and a full load of fuel. Another Avenger lifted off without the added weight and drag of the system, but Crockett’s plane failed to take-off from a loss of power and went into the water. Investigators reported that the crash “demolished” the Avenger, and surmised that the extra equipment may have caused the accident. All three men survived with minor injuries and were retrieved from the water.

Ens. Robert E. Edwards, USNR, AMM2c Nicholas Van Dyken, USNR, and ARM2c Kenneth C. Carlson, USNR, flew the second torpedo bomber (BuNo 45456) and saw Crockett’s crew go into the sea. Edwards and his men grew concerned and made a tight turn at low altitude to circle while endeavoring to spot the scene of the first plane’s crash. The investigators conjectured that Edwards may not have realized the stall limitations of the Mk. IV and he also crashed into the swells, and the plane sank immediately. A plane guard destroyer rescued the pilot, who broke both his ankles and his nose, and suffered cuts about his face, along with Van Dyken, who sustained a broken ankle, but Carlson perished in the mishap. Kalinin Bay reached Majuro on 23 April, and the task group was dissolved and she reported to Task Force (TF) 57 for further orders.

The warship did not have to wait long as she and her two faithful escorts, Bailey and Capps, almost immediately formed TG 57.14 and unsuccessfully hunted for enemy submarines off Mili Atoll (25 April–1 May 1944). On that date, they rendezvoused with TG 11.1, comprising Fanshaw Bay (CVE-70), Cabana (DE-260), Elden (DE-264), Harold C. Thomas (DE-21), and Wileman (DE-22), and set course for Hawaiian waters. Rear Adm. Gerald F. Bogan, Commander, CarDiv 25, broke his flag in Fanshaw Bay as the OTC as the ships proceeded on their journey and stood into Pearl Harbor (1–6 May).

Kalinin Bay trained and prepared for her next endeavor, Operation Forager—landings in the Marianas Islands. The ship served as part of TU 52.14.2, which joined TG 52.15, also comprising Fanshaw Bay, Midway (CVE-63), White Plains (CVE-66), Callaghan (DD-792), Cassin Young (DD-793), Irwin (DD-794), Longshaw (DD-559), Porterfield (DD-682), and Ross (DD-563). Rear Adm. Bogan broke his flag in command of the task group in Fanshaw Bay. Kalinin Bay and her embarked aircraft trained rigorously (15–19 May) and on the 18th, Lt. (j.g.) Lawrence E. Johnson, USNR, crashed in an FM-2 Wildcat (BuNo 16140) he flew from the carrier. A destroyer rushed to the area and retrieved Johnson, and later returned the pilot to the ship. The group concluded the regimen of exercises and then returned to Pearl Harbor to refuel and provision.

Planners briefly shuffled the ships and restructured some of their organization into TU 52.14.2, consisting of Fanshaw Bay, Kalinin Bay, White Plains, Callaghan, Longshaw, and Porterfield. The six ships escorted the other three destroyers and 19 vessels of TG 52.16, Rear Adm. Harry W. Hill, who hoisted his flag in attack transport Cambria (APA-36), as they set out for the battle (30 May–9 June 1944). On the 1st a Japanese submarine attacked Kalinin Bay as she steamed in the formation. Lookouts sighted two torpedoes on an apparent course of 250° (all bearings are true), the first off the ship’s port bow at a distance of 75 yards, and the second off her starboard bow at 50 yards. Both of the deadly weapons rushed toward the ship perilously close and, in all likelihood, had already approached too close to avoid them. Men braced for what seemed to be the inevitable impact, but the torpedoes narrowly missed as they passed on each side of the ship and continued on and disappeared off the starboard bow. “The ‘K.B.’ had seen death,” her historian observed, “but her number was not yet up.” None of the destroyers acquired a positive sonar contact, and the enemy boat eluded detection and escaped.

Less than a week later, on 7 June 1944, during recovery operations, Ens. George H. Aldred, USNR, brought in his Avenger (BuNo 16848) but entered the groove in a low attitude and skidding slightly to starboard. He did not answer the landing signal officer’s (LSO’s) frantic low signal, and added little or no throttle, although he did raise his nose to some extent. The LSO had no alternative but to give him a “cut” signal, but the Avenger hit the deck hard, the hook caught the No. 1 wire, and it skidded from starboard to port and continued into the port gun gallery. The plane ended up in a position that prevented the crash crew from salvaging the damaged torpedo bomber, and they jettisoned it over the side. Aldred and his crew, PhoM2c Edwin F. Abbott, USNR, and AMM3c Joseph M. Westholder Jr., USNR, escaped with minor injuries.

Kalinin Bay touched at Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshalls on 9 June 1944, and at 0648 on the 11th sortied with the other ships of TG 52.14 and sailed for Saipan in the Marianas. Fanshaw Bay (the group’s flagship), Midway, Cassin Young, Irwin, and Ross sailed as Escort Carrier Unit 1, TU 52.14.1, Rear Adm. Bogan. Kalinin Bay, White Plains, Callaghan, Longshaw, and Porterfield steamed as Escort Carrier Unit 2, TU 52.14.2. These two task units operated to support Attack Groups 1 and 2, respectively. Ens. Samuel B. Francovich, USNR, crashed over Kalinin Bay’s port bow in a Wildcat (BuNo 16492) on 11 June. A plane guard destroyer rescued Francovich, who suffered from a minor head injury, and returned him to the ship.

A Japanese Mitsubishi G4M1 Type 1 land attack plane tangled with Kalinin Bay during the afternoon watch on 14 June 1944. Low scattered clouds dotted the sky at 2,000 feet with 2/10th cover, and the visibility was unlimited. The ship launched Lt. Patsy Capano, USNR, and ARM2c Malcom J. Gordon in a TBM-1c of VC-3 on a sector patrol, escorted by Lt. (j.g.) Johnson in an FM-2. The Avenger carried four 3.5-inch rockets and three depth charges, though in this case, the crew’s two .50 caliber and one .30 caliber machine guns proved more useful. The planes spotted the olive green Betty and fired machine gun bursts that splashed the bomber in flames. Kalinin Bay reached the eastern coast of Saipan on 15 June and commenced air operations in support of the invasion, maneuvering in an area from five to 35 miles east of the island.

Forager penetrated the inner defensive perimeter of the Japanese Empire and triggered A-Go—a Japanese counterattack that led to the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The enemy intended for their shore-based planes to cripple U.S. air power in order to facilitate their carrier strikes strikes—the ships were to refuel and rearm on Guam. Japanese fuel shortages and inadequate training bedeviled A-Go, however, and U.S. signal decryption breakthroughs enabled attacks on their submarines that deprived the enemy of intelligence. Raids on the Bonin and Volcano Islands furthermore disrupted the enemy’s aerial staging en route to the Marianas, and their main attacks passed through U.S. antiaircraft fire to reach the carriers.

The Japanese struck back vigorously and at 1715 on 15 June 1944, Fanshaw Bay received a report of five of their planes heading toward her at high speed, 71 miles to the southeast. White Plains launched four FM-2s of VC-4 as combat air patrol (CAP), and controllers vectored them to intercept the attackers. The Wildcats intercepted the bombers at a range of 36 miles from Fanshaw Bay and splashed three of them, and turned and pursued the fourth one, which they caught and shot down within sight of the warship. In the meanwhile, at 1809, Fanshaw Bay catapulted her own Wildcats into the fray; however, the fifth attacker eluded all of the interceptors and dropped a torpedo at Fanshaw Bay at 1812. Capt. Douglass P. Johnson, the commanding officer, ordered “full right rudder” and the ship heeled over sharply as the torpedo churned by. Lt. Crissie C. Sanders flew one of the ship’s Wildcats and splashed the determined bomber three minutes later.

Japanese planes attacked the formation in several groups on the evening of 17 June 1944. At 1725, Kalinin Bay’s radar operators detected what they reported as “a large enemy raid” on their screen at 210°, distance 116 miles. The radarmen estimated the flight to be 20 to 30 planes, and the attackers continued to close, so when they reached a positon at 150° and 64 miles the ship sounded general quarters, and launched eight Wildcats as CAP. Fanshaw Bay’s combat information center (CIC) meanwhile reported as many as 70 unidentified aircraft approaching from the southeast at a range of 40 miles. The ship also manned her battle stations as pilots and crews scrambled to man their planes. In a few minutes, Fanshaw Bay launched 14 aircraft into the ether to join 32 planes from other carriers.

Enemy planes nonetheless fought their way through the CAP and attacked the carriers from all sides in a desperate onslaught. Wildcats tangled with the attackers, and shipboard 20- and 40-millimeter guns added their firing to the cacophony. Fanshaw Bay’s fighters claimed one of the enemy planes, and her guns splashed as many as three more, and claimed a fourth and a fifth damaged. The gathering darkness and the confusion as ships in the screen fired their guns prevented witnesses from accurately determining which ships claimed which attackers. American antiaircraft fire damaged several U.S. planes during the mêlée, though apparently did not shoot any down.

Kalinin Bay lost two VC-3 fighters (BuNos 16123 and 16224) during the fierce fighting. The Japanese shot down Ens. James T. Cuzzort, USNR, one of her youngest pilots, in an FM-2 (BuNo 16785), and he was declared missing. Initially unbeknownst to his grieving shipmates, however, Cuzzort ditched his plane in the “drink” in the very midst of the battle and hastily clambered out of the sinking Wildcat and into his small life raft. The man lacked a light with which to signal nearby ships and entered the raft wet and shivered from the cold. He splashed into the water on the windward side of Saipan, still mostly held by the Japanese, and used his parachute as a sea anchor to prevent him from drifting into the beach and likely capture—or execution. Cuzzort floated for nearly 17 hours into the next day until he finally saw Pocomoke (AV-9), and used his mirror to attract the seaplane tender’s attention. A lookout sighted the pilot and dutifully reported his sighting, but the officers standing watch at first surmised that the glint from Cuzzort’s mirror originated from the sun’s rays on a drifting tin can and nearly decided to pass him up. Nonetheless, they fortuitously agreed to lay to and spotted and picked the man up, and placed him ashore in the U.S.-held portion of the blood-soaked island. The VC-3 commander flew over and retrieved the pilot and returned him to the ship on the 29th.

Lt. Joseph W. Murphy, USNR, splashed into the swells but Cassin Young rescued the pilot. Lt. (j.g.) Leona R. Porterfield, USNR, also hit the water but White Plains lowered a boat that retrieved him, and Murphy and Porterfield returned to the ship on the 25th. Kalinin Bay also recovered nine aircraft from other carriers. In addition, an enemy plane dropped a bomb that damaged Fanshaw Bay, and she came about for repairs at Pearl Harbor Navy Yard.

The battle cost the carriers a number of planes and they desperately needed replacements. Kalinin Bay consequently carried out transfers and temporarily sent an Avenger to Midway, and a pair of Sentinels carrying four marine officers completed their duty on board and flew the planes to Saipan. Seventeen fighter pilots from other ships reported on board to assist the 17 from VC-3, one from VC-65, and four from VC-68 already on board, in ferrying aircraft to and from Eniwetok. These men helped transfer all of the “flyable” Wildcats off the ship to other carriers, which left only three FM-2s in Kalinin Bay, two of which originated from other ships.

Ross then escorted Kalinin Bay as she departed the fighting and steamed to the waters to the west of Eniwetok (19–22 June). Upon reaching that area she launched 11 Avengers carrying 39 fighter pilots as passengers, which landed at Stickell Field on Eniwetok. These pilots manned what the ship’s historian reported as “the maximum number of FM-2 type aircraft assembled there for transportation to TG 52.14 in the Saipan area,” and then flew 42 FM-2s, along with an additional five TBM-1Cs, to the ship from Naval Air Base Eniwetok. The ship packed the aircraft on board, and made some room by sending six Avengers that required work to Carrier Aircraft Service Unit (CASU) 35 at Stickell Field. Time was of the essence and so Kalinin Bay swung around, rang up flank speed, and, in company with Ross, the two ships crashed through the swells as they raced back to the Marianas.

Returning to the Battle of Saipan on 24 June 1944, Kalinin Bay delivered five Wildcats to other carriers and resumed effective air strikes against enemy positions on the embattled island. Additional men from other squadrons sailed on board Kalinin Bay during the bustle of transfers, and the five VC-4 pilots and five from VC-65 returned to their respective carriers—White Plains and Midway. Another VC-68 pilot reported on board, making a total of 18 pilots from that squadron embarked.

Bogan directed the ship to become a “Fighter Carrier” on the 25th. The men of VC-3, along with three additional pilots from VC-68, who had survived the Japanese attack against their ship, Fanshaw Bay, and transferred over to Kalinin Bay, briefly augmented their two squadrons into a single unit, jointly flying FM-2s and TBM-1c’s. Lt. Cmdr. Richard S. Rogers, VC-68’s commanding officer, led the combined squadron. Kalinin Bay launched fighters that flew CAP over the task group from sunrise to sunset on the 26th, and at 2300 that night, the ship sounded general quarters when radar tracked an estimated two to three unidentified low flying planes approaching from 270° at ten miles. The culprits turned out to be a pair of enemy bombers and just before midnight they made a low altitude run over the formation and attacked with torpedoes. Porterfield splashed one of the attackers at 2351, and the torpedoes missed.

Kalinin Bay continued to launch patrols of four or eight Wildcats that protected the ships and on 28 June 1944, did so from sunrise minus 30 minutes to sundown. A lookout sighted a torpedo wake churning toward the formation and the OTC ordered all of the ships to make an emergency turn and increase speed to 17 knots. The torpedo passed without striking any of the vessels, but although destroyers searched for the submarine with their sonar, they failed to acquire contact. Gambier Bay (CVE-73), Kitkun Bay (CVE-71), and their screen joined the formation later that evening on the 28th. The carrier task organization of TG 52.14 was then dissolved and reformed. Kalinin Bay, Midway, and White Plains, plus their screen, formed TU 52.14.1, led by Bogan. Rear Adm. Harold B. Sallada commanded TU 52.14.2 from his flagship, Kitkun Bay, which also comprised Gambier Bay, Nehenta Bay (CVE-74), and their escorts.

The fighting continued unabated ashore and Lt. Roy Anderson went down in a Wildcat (BuNo 16767) he piloted from Kalinin Bay over Saipan on 29 June, but a destroyer rescued Anderson and eventually returned him to the carrier. On 2 July, a Mitsubishi G4M1 Type 1 land attack plane dropped a torpedo at the ship but the weapon overtook the carrier, missed and exploded, and the Betty flew off and disappeared into the distance. The ship celebrated Independence Day in true fashion but just the next day lost a Wildcat (BuNo 46953) over Saipan. The sobering trend of losses continued and on 7 July, Kalinin Bay lost two VC-3 Wildcats. Lt. Richard T. Brown, USNR, was shot down and killed in an FM-2 (BuNo 46988) over Tinian. Ens. Edward P. Van Hise Jr., USNR, also went down in a fighter he was flying over Tinian, though he survived the harrowing experience.

Bogan ordered Kalinin Bay, White Plains, Cassin Young, Irwin, and Ross to come about on 9 July 1944 and make for Eniwetok. Ens. Vincent Yarashes, USNR, crashed in a Wildcat (BuNo 47324) off Kalinin Bay’s bow during a routine take-off on the 10th. Yarashes and his plane disappeared into the swells and searchers failed to locate the pilot or his fighter. Kalinin Bay shifted to CarDiv 24 on the 12th, and on that date, S1c Arlen A. Walter fell overboard and despite a thorough search, disappeared. The following day, the ship ceased to be a “Fighter Carrier” when she transferred off the fighter pilots from VC-68, and the VC-3 torpedo bomber crews returned.

Kalinin Bay next took part in Operation Stevedore—the liberation of Guam from the Japanese. TF 53, Rear Adm. Richard L. Conolly, landed the Third Marine Division, First Provisional Marine Brigade, and the Army’s 77th Infantry Division on the island. The ship joined TU 53.7.2, Rear Adm. Felix B, Stump, ComCarDiv 24, alongside Coral Sea (CVE-57), Corregidor (CVE-58), Bullard (DD-660), Chauncey (DD-667), and Hale (DD-642). Chenango (CVE-28), Sangamon (CVE-26), and Suwanee (CVE-27) also sailed under Rear Adm. Van H. Ragsdale, ComCarDiv 22, as TU 53.7.1, the two task units forming TG 53.7. Rear Adm. Lawrence F. Reifsnider embarked in George Clymer (APA-27) as the OTC.

Rear Adm. Stump operated his ships to the east of Guam (17–21 July 1944) and on the 22nd, Reifsnider’s other ships joined them—Reifsnider shifted his flag to Sangamon. Kalinin Bay launched direct support sorties and submarine patrols until 2 August, and three days later returned to Eniwetok with TG 53.7 to prepare for operations in the Palau Islands. Upon her arrival at Eniwetok, the task group was dissolved, and the ship refueled and provisioned.

Kalinin Bay cleared Eniwetok on 18 August and proceeded to Purvis Bay in the Florida Islands [Nggela] of the Solomons. Rear Adm. Walden L. Ainsworth served as the OTC in Honolulu (CL-48) as he led the carriers and their screens, reinforced by the vessels of Cruiser Divisions 9 and 12 and Destroyer Squadron 56, eastward toward those islands, which the Allies and Japanese had hotly contested in 1942–43. Kalinin Bay participated in fleet tactical maneuvers in support of amphibious landings in an area to the southward of Guadalcanal (29–30 August and 31 August–1 September). Rear Adm. William D. Sample sailed in Marcus Island (CVE-77) as the OTC.

Heading westward on 4 September 1944, the ships of TU 32.7.2, Rear Adm. George R. Henderson, ComCarDiv 28, built around Kalinin Bay, Petrof Bay (CVE-80), and Saginaw Bay (CVE-82), escorted an assault force of transports and dock landing ships for Operation Stalemate II—the landings of the First Marine Division on Peleliu and Angaur Islands in the Palaus. Henderson broke his flag in Saginaw Bay as he carried out the task unit’s mission of furnishing air coverage for Peleliu Movement Group 2 and Angaur Movement Group 2 while en route to those islands. The carriers launched daily CAP and antisubmarine patrols to protect the marines during the passage until they reached their operating area southeast of Peleliu on the 15th.

The Japanese had prepared their main line of resistance on Peleliu inland from the beaches to escape naval bombardment, and three days of preliminary carrier air attacks in combination with intense naval gunfire failed to suppress the tenacious defenders. The ship hurled her planes against the enemy each day of her deployment to the battle (15–25 September 1944) as they flew almost 400 sorties—photographic reconnaissance flights, bombing and strafing runs, CAP, and antisubmarine barrier patrols to protect the ships operating offshore.

Lt. (j.g.) John J. Perrell Jr., USNR, went down in the Avenger (BuNo 46049) he was flying from Kalinin Bay on 15 September, but a destroyer rescued the pilot. Kalinin Bay concluded her support of the hard-pressed marines and swung around and anchored in Kossol Roads in the Palaus on the 25th, and replenished the ammunition magazines. Lt. William E. Simpson, USNR, of VC-3 crashed in a Wildcat (BuNo 16427) on 27 September but survived the mishap. The Army’s 81st Infantry Division later reinforced the marines and the final Japanese on Peleliu only surrendered on 1 February 1945.

Meanwhile, on 30 September 1944, Savo Island (CVE-78) and Thorn (DD-647) joined TU 32.7.2, which was dissolved and the combined ships formed TU 32.17.16, and steamed to Seeadler Harbor, Manus Island, in the Admiralties (30 September–3 October). Kalinin Bay prepared for her next endeavor, Operation King Two—landings in Leyte Gulf. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, USA, intended to develop Leyte in the Philippines as an air and logistics base to support the liberation of the islands. Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid, Commander Seventh Fleet, was to land the Sixth Army’s 1st Cavalry and 7th, 24th, and 96th Infantry Divisions, of the X and XXIX Corps. Gen. Walter Krueger, USA, led the Sixth Army.

Fanshaw Bay, Kalinin Bay, St. Lo (CVE-63), and White Plains formed TU 77.4.31 and cleared Manus on 12 October 1944. Rear Adm. Clifton A.F. Sprague, ComCarDiv 25 hoisted his flag in Fanshaw Bay in command of the task unit, which provided air coverage for the Bombardment and Fire Support Group, TG 77.2, Rear Adm. Jesse B. Oldendorf. As the soldiers landed, the carriers were to furthermore “provide close support for the bombardment beach reconnaissance and landing operation in the Leyte Gulf area.”

Sprague broke away from Oldendorf on the 16th and set course for an assigned operating area eastward of Leyte Gulf and Samar. Planes from the escort carriers flew CAP, air support, and strike missions for the Army’s Sixth Ranger Battalion as they landed on Dinagat and Suluan Islands, at the eastern approaches to Leyte Gulf, to destroy Japanese installations capable of providing early warning of a U.S. attack, on 17 October. The garrison on Suluan transmitted an alert that prompted Japanese Commander in Chief Combined Fleet Adm. Toyoda Soemu to order Shō-Gō 1—an operation to defend the Philippines. The raid thus helped to bring about the Battle of Leyte Gulf, a succession of distinct fleet engagements. The following day, Kalinin Bay and her consorts shaped a course to rendezvous with other ships, and two days later on the 20th, they joined up and their task organization changed.

Adm. William F. Halsey Jr., Commander, Third Fleet, led nine fleet and eight small carriers into those troubled waters. Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid, Commander, Seventh Fleet, led a force that included TG 77.4, Rear Adm. Thomas L. Sprague—consisting of 18 escort carriers organized in TUs 77.4.1, 77.4.2, and 77.4.3, and known by their voice radio calls as Taffys 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Chenango, Petrof Bay, Saginaw Bay, Sangamon, Santee (CVE-29), and Suwanee and their screens formed Taffy 1, Rear Adm. Thomas L. Sprague, and fought off northern Mindanao. Chenango and Saginaw Bay swung around on the 24th to carry planes to Morotai in the Netherlands East Indies [Indonesia] for repairs and overhaul. Kadashan Bay (CVE-76), Manila Bay (CVE-61), Marcus Island, Natoma Bay (CVE-62), Ommaney Bay (CVE-79), and Savo Island of Taffy 2, Rear Adm. Stump, operated off the entrance to Leyte Gulf.

Kalinin Bay steamed with the two CarDivs of Taffy 3, Rear Adm. Clifton Sprague, off Samar. Fanshaw Bay, Gambier Bay, St. Lo, and White Plains formed CarDiv 25, Rear Adm. Sprague, who broke his flag in Fanshaw Bay, while Gambier Bay and Kitkun Bay comprised CarDiv 26, Rear Adm. Ralph A. Ofstie. Heermann (DD-523), Hoel (DD-533), Johnston (DD-557), Dennis (DE-405), John C. Butler (DE-339), Raymond (DE-341), and Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413), screened Taffy 3. Their mission was principally to operate “in support of the landings in the Tacloban area, northeast coast of Leyte Island, P.I. [Philippine Islands].”

Kalinin Bay’s aircraft flew 244 sorties against enemy installations and airfields on Cebu, Leyte, Negros, Panay, and Samar in the opening phases of the battle (18–24 October 1944). On the 20th, the ship marked her 1,000th catapult shot as Ens. James R. Zeitvogel, ARM3c H.A. Henderson, USNR, and ARM3c C.P. Iwuc, USNR, launched, and the Avenger crew and their maintainers celebrated the event with cake.

The fighting continued unabated, however, and a flight of 21 Japanese bombers attacked some of the transports anchored in Leyte Gulf on 24 October 1944. The enemy artfully flew another plane, a Kawasaki Ki.48, toward the anchorage as a decoy. Radar operators directed the U.S. fighters to intercept the enemy aircraft, and Lt. Kenneth C. Hippe, USNR, led a four-plane division of Wildcats at 10,000 feet that splashed the Lily. Hippe and his men discovered the Japanese attack group winging in a vee formation from the west at a higher altitude, however, and straight toward the vulnerable troopships. Hippe fired all of his 1,720-rounds as he “led his flight in repeated attacks…and, by personally shooting down five Japanese bombers” assisted in saving the transports, a feat for which he subsequently received the Navy Cross.

“Realizing the urgent necessity for destroying this formation before it could attack,” Ens. John Buchanan, USNR, persistently attacked the enemy and splashed three of the bombers. Buchanan’s actions also “contributed materially to the destruction of this force,” and he afterward received the Distinguished Flying Cross. In all, U.S. fighters from the carriers claimed to splash 19 of the attackers in a swirling battle in the Philippine skies.

Kalinin Bay lost two VC-3 Wildcats during the battle. Lt. Simpson collided with an enemy aircraft he engaged in a fighter (BuNo 46994) he flew from the carrier against the Japanese in the aerial mêlée, but this time he did not survive the crash. Ens. William D. McDaniel, USNR, went down in the plane (BuNo 47346) he piloted, but escaped and was returned to the ship.

In the meantime, the Japanese launched Shō-Gō 1 to disrupt the U.S. landings in Leyte Gulf. Acute fuel shortages drove them to disperse their fleet into the Northern (decoy), Center, and Southern Forces and converge separately on Leyte Gulf. Attrition had reduced the Northern Force’s 1st Mobile Force, their principal naval aviation command and led by Vice Adm. Ozawa Jisaburō, to carrier Zuikaku and light carriers Chitose, Chiyōda, and Zuihō. The Center Force, Vice Adm. Kurita Takeo in command, comprised two commands. Force A initially sailed with battleships Musashi, Yamato, and Nagato, heavy cruisers Atago, Chōkai, Haguro, Maya, Myoko, and Takao, light cruiser Noshiro, and destroyers Akishimo, Asashimo, Fujinami, Hamanami, Hayashimo, Kishinami, Kiyoshimo, Naganami, Okinami, and Shimakaze. Force B comprised battleships Haruna and Kongō, heavy cruisers Chikuma, Kumano, Suzuya, and Tone, light cruiser Yahagi, and destroyers Hamakaze, Isokaze, Urakaze, and Yukikaze.

Submarines Darter and Dace (SS-247) attacked what turned out to be the Japanese Center Force. Dace sank heavy cruiser Maya, and Darter sank Atago and damaged her sistership Takao, which came about for Brunei. The planes of TG 38.2, TG 38.3, and TG 38.4 attacked Kurita as he led the ships across the Sibuyan Sea. Aircraft from Enterprise, Intrepid (CV-11), Franklin (CV-13), and Cabot sank Musashi south of Luzon. Planes from the three groups furthermore damaged Yamato, Nagato, Tone, Fujinami, Kiyoshimo, and (separately) Uranami. Ozawa in the meanwhile decoyed Halsey’s Third Fleet northward, and aircraft eventually sank all four Japanese carriers, Chitose with the assistance of cruiser gunfire, off Cape Engaño. Halsey’s aggressive pursuit, however, took his force beyond the range at which it could protect Taffy 3.

Intermittent rain squalls passed through the area as the day dawned at 0614 on Wednesday, 25 October 1944. The visibility gradually increased to about 40,000 yards with a low overcast (three tenths cumulous clouds), the sea was calm, and the wind was from a north-northeasterly direction. Kalinin Bay and the other ships of Taffy 3 greeted the day preparing to launch strikes to support the troops attempting to move inland. They thus armed their planes with light bombs and rockets to attack Japanese soldiers and positions, or depth charges to fly antisubmarine patrols. The escort carriers launched a dozen Wildcats as Target CAP for their strikes beginning at 0530, and at 0607 the first of four Avengers as an antisubmarine patrol—and to augment the local CAP.

Unbeknownst to Kalinin Bay and the other ships of Taffy 3, however, Kurita’s surviving vessels, which included Yamato, Haruna, Kongō, and Nagato, Chikuma, Chōkai, Haguro, Kumano, Suzuya, Tone, Noshiro, Yahagi, and 11 Kagerō, Shimikaze, and Yūgumo class destroyers, slipped through San Bernardino Strait into the Philippine Sea.

Ens. William C. Brooks, Jr., USNR, of Pasadena, Calif., flew a TBM-1C of VC-65 from St. Lo and sighted some of the Japanese ships at 0637 on 25 October 1944. Brooks initially believed them to be Allied reinforcements, but he followed established procedure and radioed a sighting report. His superiors demanded confirmation and when he closed the range, he saw pagoda masts and positively identified some of the enemy vessels. Undaunted by the Japanese firepower, Brooks and his Avenger crewmen twice attacked a Japanese heavy cruiser, and dropped depth charges that bounced off the ship, and then joined a pair of Avengers that dived on a battleship, feats of extraordinary heroism for which Brooks later received the Navy Cross.

Lookouts on board the ships of Taffy 3 saw the Japanese antiaircraft fire explode on the northern horizon at 0645, and within minutes, radar operators began to detect the approaching Japanese vessels, while other sailors intercepted enemy message traffic. The Japanese surprised the Americans and caught Taffy 3 unprepared to face such a seemingly overwhelming assault, and the battle quickly became a precipitate flight in the face of the powerful enemy force. Sprague ordered his ships to come about to 090° at 0650, and flee to the eastward, hoping that a rain squall would mask their escape. The carriers scrambled to launch their planes, and the escorts steamed to what quickly became the rear of the formation to lay smoke screens.

A report of the sudden appearance of four enemy battleships, six heavy cruisers, and a number of destroyers, bearing 270° at 20 miles reached Capt. Williamson at 0654 on 25 October 1944. Three minutes later, Williamson ordered “All engines ahead at flank speed. Sound general quarters! Change course to 090° and all prisoners released from the brig.” Men also passed the word over the Inter-fighter Director Net (37.6 mcs), and then heard “excited” Japanese voices on the same frequency. The net’s operators tested the frequency and found that the enemy indeed talked directly on the same cycle. Kalinin Bay’s crew raced to man their battle stations, and the ship likewise sounded flight quarters as she accelerated to flank speed.

Despite the gunfire from three enemy cruisers, bearing 270° at 34,500 yards, she launched all of the available planes, and ordered the pilots “to attack the Japanese task force, then proceed to Tacloban airfield [at the northwest end of Leyte Gulf on Leyte] to re-arm and re-gas.” Kalinin Bay’s available planes comprised two TBM-1c’s each armed with eight 5-inch rockets and two 500-pound general-purpose bombs, another half dozen Avengers loaded with eight rockets and six 100-pound bombs, and 13 Wildcats with their full load of .50 caliber ammunition.

The rain squalls and smoke screens imposed multiple delays and some of the aircraft launched in different groups. Lt. Cmdr. William H. Keighley, USNR, VC-3’s commanding officer, Ens. Richard G. Altmann, USNR, Lt. Capano, Lt. (j.g.) Edward J. Green, USNR, Lt. (j.g.) James E. Merchant, USNR, and Lt. (j.g.) Perrell hurried aloft in six Avengers armed with a mix of 5-inch rockets and bombs in the first group. Lt. Crockett led a second flight that included Lt. E.L. Archer Jr., USNR, Ens. George N. Smith, USNR, and Ens. Zeitvogel.

Taffy 3 called for help as Fanshaw Bay broadcast an urgent contact report on 2096 kilocycles, in plain language, voice, giving the task unit’s position, bearing, and distance from the enemy, and requesting immediate assistance, at 0701. The Japanese “volume and accuracy of fire was increasing,” Sprague later reported to Adm. Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, on 29 October 1944, as salvo after salvo fell “with disconcerting rapidity.”

“At this point,” the admiral added ominously, “it did not appear that any of our ships could survive another five minutes of the heavy caliber fire being received, and counter-action was urgently and immediately required. The Task Unit was surrounded by the ultimate of desperate circumstances. All escorts were ordered to attack the enemy with torpedoes. At this time direct view of the enemy was obscured by smoke and results of our escorts attack could not be ascertained, but it is believed that, regardless of hits, they succeeded in turning the battleships away at least momentarily, and created a diversion of immense value.”

Kalinin Bay led the formation while the carriers turned to the eastward, but as the formation changed course to 180° to the south to keep the enemy astern and escape at 0723 on 25 October 1944, she became the trailing ship in the escort carrier van. Some crewmen grimly referred to her as “Tail-end-Charlie.” White Plains switched from the rear to the van of the formation, flanked (in order) by Kitkun Bay and Gambier Bay to port, and Fanshaw Bay and St. Lo to starboard. This change in the ships’ dispositions meant that Kalinin Bay weathered an intense storm of enemy fire.

Throughout the morning, Kalinin Bay’s Wildcats and Avengers joined other planes that repeatedly bombed and strafed the Japanese warships. Some aircraft launched lightly armed, and, along with those that quickly dropped or fired off their ordnance, flew dummy runs against the enemy vessels, in some instances to divert their antiaircraft fire from the other planes.

Keighley and his men flew their planes through a hole in the clouds at 8,000 feet and sighted a Kongō class battleship (Haruna or Kongō), Nagato, Chikuma, Tone, two Nachi class heavy cruisers (likely Haguro and one of the other cruisers), and a number of destroyers at 0740. Keighley ordered his pilots to attack and he pushed over and fired six rockets at a Tone class heavy cruiser (either Chikuma or Tone), straddling the enemy warship from her starboard quarter to just aft of amidships on the port side, and scoring hits with three of the bombs he dropped.

Crockett joined up and turned toward a Kongō class battleship, the only vessel he could see through the overcast, until he reached 1,000 feet and a number of other ships emerged into view. The other Kongō steamed ahead of the first one he glimpsed (the second in the column), and a trio of heavy cruisers plowed along on the battleships’ port sides. Crockett flew up their stern on the same course, dropped his bombs, and pulled up through heavy antiaircraft fire. The Japanese guns fired accurately and shot down the following Avenger, which crashed into the sea.

Smith joined up with Crockett and dived on Chikuma or Tone. The pilot apparently surprised the enemy gunners because they failed to open fire until he started firing his eight rockets, five of which hurtled into the superstructure. Smith furthermore dropped two 500-pound bombs from an altitude of 4,000 feet, one of which burst about 15 feet from the heavy cruiser’s stern, and the second about 30 feet off her bow. Smith pulled up to 1,500 feet from his dive but the enemy gunfire compelled him to climb to 2,000 feet.

Archer met Smith in the midst of these runs and spotted eight Japanese destroyers in column. The pilot dived from 6,000 to 500 feet and strafed the last two ships, and pulled up steeply into a rain squall. Archer climbed to 8,500 feet and joined seven Avengers and ten Wildcats flying to attack the heavier warships. As the group entered a cloud some of the men sighted a battleship and two cruisers in column, the latter beginning to turn to port. Archer flew as the third plane in the formation and released his bombs from a height of 4,500 to 3,000 feet against the second cruiser. Continuing his dive at about 30° toward the leading cruiser, he walked eight rockets up her deck, two of which exploded against the bridge, knocking part of it off.

Capano led his flight and attacked the leading Japanese cruiser with 5-inch rockets, and then joined up with Keighley and strafed Chikuma or Tone. Capano pulled up to the left and Keighley to the right, but no one ever saw Capano again as the enemy gunners shot down another plane. Merchant fired his rockets and they straddled a Nachi class cruiser, and he claimed to also hit her with three of his bombs. Altmann dropped to 5,000 feet directly over Nagato, and then dived, shot his 5-inch rockets and dropped two 500-pound bombs. The rockets hit amidships and the ensuing explosion generated black smoke. The first bomb struck Nagato’s port bow, and the second fell within 25 feet of her port bow. Perrell launched without ammunition and flew southward to look for the carriers of Taffy 2 so that he could land on board one of them and load. The Japanese shot down Lt. Porterfield in the Wildcat (BuNo 16347) he was flying, but Porterfield survived and later returned to the ship.

Smoke screens, a timely rain squall, and the valiant counterattacks of the screening destroyers and escorts partially protected Kalinin Bay, but she took the first of 15 direct hits at 0750 on 25 October 1944. The Japanese battleships fired blood red, pink or greenish-yellow dye-loaded projectiles in order to mark their fire, and Sprague referred to their huge splashes as “very distinctive.” Haruna fired a salvo of 14-inch rounds from a range of 16,998 yards that straddled the carrier, and one of the shells struck the starboard side of the hangar deck just abaft the forward elevator on the hangar deck. Sailors recovered fragments of the large caliber shell on the hangar deck.

Chikuma, Tone, and a Nachi class cruiser closed on Kalinin Bay’s port quarter to within 18,000 yards by 0800, and Kalinin Bay gamely responded to their straddling salvos with rapid fire from her single 5-inch gun. The radarmen in the CIC continuously tracked the enemy vessels on their radar repeaters and the Dead Reckoning Tracer, and passed their ranges, courses, and speeds to gunnery control on the bridge (0720–0904). The men there, in turn, relayed the information to the gunners, which proved invaluable as they engaged the Japanese in the unequal duel until they were knocked out (see below).

The Japanese cruisers fired repeated salvoes at Kalinin Bay and three 8-inch, armor-piercing projectiles struck her within minutes of each other. The first of the shells burst under the counter of the carrier’s fantail on the port side, showering fragments into the hull at frame 203.5 The explosion beneath the bottom plating twisted and warped the deck and beams in the pyrotechnic locker C-308-M, and water poured in and flooded the compartment up to a depth of six feet. A second round in a following salvo detonated just off the fantail, sending fragments into the stern on the port side into the mess attendants’ compartment C-204-16L and continued on and tore into bulkhead 199.

The ship’s 5-inch gunners scored what they believed was a direct hit on a Nachi class heavy cruiser’s No. 2 turret at 0825. The gunners redoubled their efforts and apparently struck the turret a second time, just below the first hit, as flames leapt up and enveloped the area. What likely happened, however, is that one of the carrier planes dropped a 100-pound bomb that knocked out Haguro’s No. 2 turret, killing 30 men and injuring 12. Flooding the turret’s magazine prevented an explosion, but the turret jammed over 30° to port with the guns at a 20° elevation. Haguro turned hard to port and temporarily fell out of formation.

Chikuma and Tone changed course to south-southeast to pursue the carriers and closed upon their port quarter. A number of U.S. officers surmised that the pair intended to encircle Taffy 3’s disposition and cut off their retreat. The enemy ships advanced almost abeam of the carriers and closed the range, hurling salvo after salvo that repeatedly straddled and hit their targets. The admiral diverted all of the available aircraft onto the warships and four Avengers from Taffy 2 swarmed the pair, one of which dropped a torpedo that punched into Chikuma and disabled her port screw and rudder. The cruiser briefly went dead in the water, and then resumed slower speed but steered erratically.

The situation nevertheless continued to deteriorate at 0830 on 25 October 1944, when Yahagi and four enemy destroyers steamed in column over the horizon off Kalinin Bay’s starboard quarter. The ship’s company debated their identity and some of the men hoped they were U.S. ships arriving to help, until the warships closed to about 14,500 yards and opened fire. Kalinin Bay turned hard to starboard and astern of St. Lo and then swung back into the formation but on the starboard quarter instead of the port quarter. As the screening vessels valiantly engaged the cruisers and laid down concealing smoke, Kalinin Bay shifted her fire and for the next hour traded shots with the Japanese destroyers.

The Japanese flanked Kalinin Bay and Haguro, which resumed her position in the formation, and Tone, continued to attack from the port quarter. Due to the fact that the destroyers also assailed the carrier from her starboard quarter, she thus did not steer evasive maneuvers. The destroyers appeared to close the range and the ship’s single 5-inch gun shot rapid fire at them instead of the more powerful cruisers. Multiple salvoes splashed into the water close aboard and other shells ripped through the air as they passed overhead.

The enemy destroyers launched a torpedo attack and lookouts on board Kalinin Bay sighted at least 12 torpedo wakes on parallel courses on either side of the carrier as the deadly weapons churned through the water but they all passed the warship.

Tone led Haguro as they closed to 10,100 yards just after 0853 and fired salvo after salvo (Tone 28 rounds) at Kalinin Bay on their starboard beam that continued to explode close aboard the carrier or pass directly overhead. None of the destroyers hit Kalinin Bay directly but she took ten more 8-inch hits. Two 8-inch shells penetrated the port side of A-301-L at frame 18 about five feet above deck level and cut through the starboard side of the hull at frame 19, the first at deck level and the second one about three feet above deck level, at around 0845. Neither round detonated, but the sea roared into the compartment to a depth of five feet and also flooded A-401-A up to four feet.

Shortly thereafter a nearly fatal attack on Kalinin Bay occurred when one of the Japanese heavy cruisers fired an 8-inch round that punched into the port side on officers’ stateroom No. 316 about a foot about deck level. The projectile continued on through the platform deck approximately four feet inboard from the port side, through storeroom A-407-A, and on into the forward section of the port aviation lube oil tank and exploded, almost passing through the bottom of the ship.

The detonation ruptured a number of fuel lines for tanks including A-909-F, A-910-F, A-911-F, A-912-F, A-915-F, and B-903-F. The blast buckled the forward bulkhead in ten places in the forward engine room along the platform deck. The Pacific poured in and men scrambled to plug the breeches with wooden plugs, standing in water that rose dangerously until it reached a depth of four feet. Fragments also scythed into the bulkheads of compartment 318 and the passageway amidships to A-407-A, which also flooded up to four feet before a damage control team plugged the holes and stopped the in-rushing sea.

Another 8-inch shell, the seventh enemy round to strike Kalinin Bay, pierced the port side of frame 51.5 at deck level of A-0102-AL and the overhead of the carpenter’s shop, hurtled across the elevator pit and into passageway A-204-1T, and clear out the starboard side of the ship at frame 53.5 a foot above the second deck.

An 8-inch round cut through the port side at the aviation armory A-301-4L between frames 103–104 about four feet above deck level, tore through the after bulkhead and into the ship’s armory B-301-6L and out the inboard bulkhead. The seemingly unstoppable projectile continued on into the first platform deck, passageway B-301-2T at frame 107, the machine shop, through B-404-F, the athwartships passage, and detonated in 3-405-W. The resulting blast ruptured fuel oil tanks B-402-F and B-904-F, as well as bulkhead 118, the forward one to the aft engine room. The shell furthermore ripped up the first platform deck at frames 106–108, and water flooded B-301-6L to a depth of ten feet. Men battled the flames in the aviation armory, ship’s armory, and machine shop for nearly an hour and a half.

One of the heavy cruisers’ main battery shells punched through Kalinin Bay’s port side at A-201-A between frames 8–9 about three feet above the deck level, and flew through the starboard side at frames 9–10 without exploding.

Another 8-inch round, the tenth to strike the ship, hit the flight deck at frame 55.5 just starboard of the forward elevator and plunged through A-0207-2T and into the forward elevator pit. The projectile broke into three pieces, each of which passed through A-0102-T and into officers’ stateroom 0117. One of the fragments emerged through frames 58–59, cutting a 2.5 foot by 5 foot hole in the starboard skin of the ship. The other two pieces flew through the ship and out the side near frames 54 and 55.5.

White Plains also fired her single 5-inch gun at one of the enemy heavy cruisers, most likely Chokai. Samuel B. Roberts fought Chokai as well, and at 0859 a secondary explosion erupted from the enemy vessel, possibly as some of her torpedoes cooked off. The blast knocked out her engines and rudder, and she sheered out of line. The other enemy cruisers continued firing and a salvo splashed barely 200 yards astern of Kitkun Bay. Haguro, which took Chikuma’s place in position, and Tone appeared to outdistance the rest of the Japanese ships and drew up toward Kitkun Bay. The enemy ships dropped the range until they closed on Kitkun Bay’s port beam at 12,000 yards, and their next salvo straddled the carrier as their shells splashed on both sides.

The Japanese continued to pound the ship and knocked out the forward elevator when they sent an 8-inch round into the flight deck at frame 59.5 outboard of the forward elevator. The projectile passed through A-0207-2T into the elevator pit, and then down to the base of the elevator and exploded, tearing holes in the elevator pit and flight deck between frames 59–61.

The enemy poured it on and another shell passed through the ship’s flight deck at frame 67 between the elevator and the island at 0904 that morning of 25 October 1944, and through the starboard radar transmitter room, radio direction finder room, and radar generator room, and burst in the radar control room, destroying all of the radar and radio equipment in its ruinous path. The damage seriously impaired Kalinin Bay’s ability to defend herself, and the ship from that moment forward experienced difficulty both in accurately tracking her tormentors and in returning fire.

An 8-inch round struck the forward starboard smoke stack, and another shell slammed into the flight deck at frame 87 amidships, penetrated the forward uptakes, and continued on through flight crew lockers and out the starboard side at frame 90.5 without exploding.

The 15th and final round to strike Kalinin Bay was an 8-inch shell that hit the flight deck at frame 119 amidships and penetrated the after uptakes, passed through the gallery deck, and out the starboard side at frame 124. Altogether, these 15 hits caused the ship to list 7° to port, and the damage control teams shifted ballast to compartments C-907-F and C-908-F, which swung her over 8° to starboard. Investigation revealed a hole in compartment A-301-L, and so they began pumping the water out of C-903-F and C-904-F, and pumping fuel into C-907-F and C-909-F, and the ship’s bow slowly rose and she righted herself.

While these rounds struck the ship the enemy destroyers launched torpedoes from a range of approximately 10,500 yards at 0915. As the lethal weapons hurtled toward the escort carriers and U.S. flak spattered the sky, Lt. Leonard E. Waldrop, USNR, flying an Avenger from St. Lo, his port wing having a two-foot diameter hole from a direct hit from Japanese AA, strafed and exploded at least one torpedo in Kalinin Bay’s wake about 100 yards astern. The carrier’s 5-inch gun fired at a depression elevation of 2° another torpedo that appeared to broach and one of its rounds splashed about ten feet ahead of the torpedo and deflected the weapon from its collision course with her stern as it turned to port.

Under heavy attack from the air and harassed by the U.S. escorts, the enemy cruisers broke off the action and turned northward at 0920. The valiant rearguard efforts threw Kurita’s ships into disarray and compelled his retirement despite the Japanese superiority in weight and firepower, and their vessels swung around and disengaged.

“At 0925 my mind was occupied with dodging torpedoes,” Sprague afterward reflected, “when near the bridge I heard one of the signalmen yell ‘They're getting away!’ I could hardly believe my eyes, but it looked as if the whole Japanese fleet was indeed retiring. However, it took a whole series of reports from circling planes to convince me. And still I could not get the fact to soak into my battle-numbed brain. At best, I had expected to be swimming by this time.”

As the Japanese fired their Parthian shots and reversed course northward at about 0930, Kalinin Bay scored a direct hit amidships on a retreating destroyer. The enemy ship heeled sharply out of line, though continued to fire at the American vessels. Five minutes later, one of the U.S. escorts steamed past Kalinin Bay’s line of sight and she ceased fire, and because the smoke screen hampered visibility. The ship then attempted to retire southward with the surviving vessels of Taffy 3. Four ships, valiantly fighting to the end, went down: Gambier Bay, Hoel, Johnston; and Samuel B. Roberts. In addition, Japanese gunfire damaged Kalinin Bay, Heermann, and Dennis, and straddled Kitkun Bay, St. Lo, and White Plains but scored no direct hits.

In the Battle off Samar and the Japanese retirement, the U.S. ships and planes damaged Yamato, Kongō, Chikuma, Chōkai, Haguro, Kumano, Suzuya, and Tone. Chikuma, Chōkai, and Suzuya suffered repeated explosions and fires and destroyers Nowaki, Fujinami, and Okinami, respectively, scuttled the cruisers with torpedoes—though Nowaki may have reached the area after U.S. aircraft delivered the coup de grâce to Chikuma. About 60 planes from TGs 38.2 and 38.4 tore into the retiring Japanese and sank Noshiro on the 26th. That day, U.S. cruisers also crippled Nowaki with gunfire, and Owen (DD-536) sank her about 65 miles south-southeast of Legaspi, Luzon. The casualties the Japanese surface fleet sustained and its virtual withdrawal to anchorages because of a lack of fuel finished it as an effective fighting force.

“The high degree of skill,” Sprague reported to Adm. King, “the unflinching courage, the inspired determination to go down fighting, of the officers and men under my command cannot be too highly praised.”

“The Japanese gunnery was good as to mean range,” Sprague added, “poor as to advance range, and with excellent patterns. It is believed they had an airborne spotter overhead. The fact that a large number of shells were AP [armor-piercing], non-explosive, resulted in much less damage from hits received. In summation, the failure of the enemy main body and encircling light forces to completely wipe out all vessels of this Task Unit can be attributed to our successful smoke screen, our torpedo counter-attack, continuous harassment of enemy by bomb, torpedo, and strafing air attacks, timely maneuvers, and the definite partiality of Almighty God.”

Capt. Williamson later received the Navy Cross for his “extraordinary heroism and distinguished service” in the day’s action. Williamson “maneuvered his ship to avoid crippling blows from the constant, three hour bombardment, and successfully brought his ship through this history-making battle, thereby contributing essentially to the eventual rout of this powerful Japanese force.”

Following Taffy 3’s ordeal off Samar on 25 October 1944, however, Japanese kamikaze suicide planes plunged into the carriers and sank St. Lo and damaged Kalinin Bay and Kitkun Bay. At least eight enemy planes swooped in beginning at 1050 and launched a concentrated air attack against the ships of the task unit. The aircraft approached from low altitudes, climbed very rapidly inside the SK radar range, and began their dives from 5,000 to 6,000 feet. Ships careened hard over as they maneuvered to avoid the determined enemy aviators, and guns blazed furiously during the 40-minute battle with the suicide planes, but the Japanese struck all of the escort carriers save Fanshaw Bay. One plane crashed through St. Lo’s flight deck and exploded her torpedo and bomb magazine, mortally wounding the gallant carrier.

Escort ships on Kalinin Bay’s starboard bow and beam fired at four diving Mitsubishi A6M Type 0 carrier fighters that attacked the carrier. The ship’s lookouts sighted the leading Zeke as it began a twisting spiral toward the ship’s starboard bow in a 60° dive. The antiaircraft guns opened fire and hit the plane, but the kamikaze crossed the starboard quarter and crashed into the port side of the flight deck at frames 120–132, damaging it badly. Eyewitnesses conjectured that the pilot pulled out just before hitting, and the plane therefore did not penetrate as deeply as might otherwise have occurred. The impact rent a hole in the flight deck and caused numerous fires that inflicted flash burns on many of the gunners manning Nos 4 and 14 20-millimeter mounts. Most of the suicide plane skidded forward along the flight deck and dropped over the port bow at frame 10. Sailors rushed to the scene of the conflagration and extinguished the flames within about ten minutes.

Lookouts sighted the second Zeke diving on the starboard quarter from an altitude of 6,000–8,000 feet at an angle of about 70°. Gunfire repeatedly hit the plane and it began smoking but defiantly crashed the ship on the port side. The impact shook the ship and destroyed the after port stack, catwalk, and 20-millimeter mount in the vicinity of frames 110–120. The Zeke splashed into the water near the port side, throwing up a large column of water. Intense fire from the escorts and Kalinin Bay’s automatic weapons splashed the other two Zekes that attempted to crash dive the ship, and the third one went into the sea close aboard about 50 yards on the port quarter. A small explosion erupted from its impact, most likely from the plane’s bomb. The attackers ceased their assault at about 1130.

The ship’s historian succinctly summarized the crew’s damage control efforts as “superb.” The men used wooden plugs to stop up waterline holes that likely saved her from sinking. Fire-fighting teams quickly doused the fires that sprang up from both the shellfire and the kamikazes, and all of the equipment, including submersible pumps, functioned as designed.

The battle altogether cost Kalinin Bay 60 casualties including nine dead: Lt. Capano, Ens. Paul Hopfner, USNR, ARM1c Gordon, RT1c Charles A. Wilson, S1c Aur Demetrescu, AMM2c Gordon E. Galloway, RdM2c Robert E. Choin, RM2c Borchard K. Gunter, and RM2c Charles R. Moran.

Kalinin Bay suffered extensive structural damage during the morning’s furious action. Two suicide planes, one 14-inch shell, and 14 8 and 6-inch rounds tore into the ship during her ordeal off Samar. The attacks wrecked the forward elevator, ruptured watertight bulkheads 82 and 118 at the deck plate level in the engine rooms, ripped one large hole and five medium holes in the flight deck, cracked nine longitudinal flight deck beams, damaged two arresting gear units, and ruptured the deck in A-308L over a gasoline void, making it impossible to maintain inner gas pressure. The enemy knocked out the SG radar, damaged the SK radar, and destroyed much radio equipment. Oil contaminated the entire fresh water system, and the risk of infections to the wounded and thirst further agonized the men, and multiple aviation lube oil tanks leaked. Kalinin Bay fired 170 5-inch, 1,750 40-millimeter, and 4,800 20-millimeter rounds that day.

Despite the battle damage, Taffy 3 cleared the air of attacking planes by noon, and the escort carriers retired southeastward on course 120° while their escorts searched for survivors from St. Lo. Kalinin Bay’s historian noted that the ship cancelled air support operations “due to battle casualties to this vessel,” and she came about with “the remnants” of the task unit.

Japanese submarine I-26 (Lt. Cmdr. Nishiuchi Shoichi, commanding) prowled in the area, a boat that had attained multiple successes against the Allies. The submarine sank unarmed U.S. Army-chartered steam schooner Cynthia Olson about 1,000 miles northwest of Diamond Head, Honolulu, T.H., on 7 December 1941. The attack marked the first U.S. merchantman to be sunk by a Japanese submarine in World War II, and none of Cynthia Olson’s 33-man crew or the two Army passengers survived. I-26 shelled the radio direction finding station and lighthouse at Estevan Point on Vancouver Island, British Columbia on 20 June 1942, an action that disrupted shipping for some time as the Allies temporarily extinguished many of the lighthouses along the coast. The Japanese submarine continued to patrol aggressively and torpedoed and damaged Saratoga (CV-3) southeast of Guadalcanal on 31 August 1942, and on 13 November of that year torpedoed and sank light cruiser Juneau (CL-52) with a huge loss of life including the five Sullivan brothers. The Japanese submarine attempted to maneuver into position to attack Petrof Bay on the night of 25–26 October 1944. At 2000 radar operators on board some of the vessels detected an unknown surface contact and began tracking the intruder, and when three of the escorts investigated the contact they discovered and attacked the enemy submarine at 2233. Either Coolbaugh (DE-217) or Richard M. Rowell (DE-403) (most likely the latter) finally put an end to I-26 (and all 105 souls on board) or the submarine sank as a result of operational issues—Japanese records do not confirm the circumstances of her loss only that the last message received from Lt. Cmdr. Nishiuchi was dated 25 October and messages to the boat on 27 October and 7 November were never answered. In addition, from six to eight enemy planes flew in the area but did not attack the ships.

The following day at 1000 on the 26th, Kalinin Bay’s ship’s company consigned to the deep the five men who died on board the ship during the battle: Wilson, Demetrescu, Choin, Gunter, and Moran. Capano, Hopfner, Gordon, and Galloway perished while flying their aircraft against the enemy ships.

As men inspected Kalinin Bay’s damage, however, they determined that the ship’s ruptured tanks were draining her fuel supply. Consequently, the OTC advised that the task unit should change course on the 27th, and the vessels made for Mios Woendi in the Schouten Islands, southeast of Biak in the Netherlands East Indies. Kalinin Bay anchored there and many of the pilots that had landed on board other ships returned, and the wounded who required further care were transferred ashore. The warship refueled and resumed the journey (30 October–1 November) to Manus, where she made emergency repairs.

Turning her prow homeward, the escort carrier steamed to Pearl Harbor en route to the West Coast (7–18 November 1944). On the 9th, Capt. Williamson commended the crew for their valor during the Battle off Samar. Fanshaw Bay, Kalinin Bay, and Heerman refueled and provisioned, and then set out as TG 19.13 across the eastern Pacific (20–27 November 1944). Upon reaching San Diego, VC-3 detached to NAS San Diego, while Kalinin Bay turned northward the following day and the same day arrived at Naval Dry Docks near San Pedro, where she accomplished repairs and alterations through the holidays.

Early in the New Year on 5 January 1945, Kalinin Bay became a part of Carrier Transport Squadron Pacific, Rear Adm. Samuel P. Ginder in command. Repairs completed on 18 January 1945, that day the veteran escort carrier returned to San Diego, which she reached late that afternoon. Kalinin Bay stood round North Island, carrying one officer and 28 enlisted sailors as passengers, and ferrying six F6Fs, 24 FM-2s, a single USMC Goodyear FG-1 Corsair, 30 TBMs, and five SB2Cs, and shaped a course for Pearl Harbor (20–27 January 1945). Designated TU 19.9.1, the ship there embarked additional passengers for a total of seven officers and 207 sailors, and loaded 3,400 cubic feet of miscellaneous cargo but retained her load of aircraft, and steamed to Guam (28 January–8 February).

Kalinin Bay disembarked her passengers and unloaded the cargo at Guam, but another 177 enlisted men boarded the ship, and she furthermore transported seven damaged aircraft (a pair of Hellcats and five Helldivers) along with 121.7 cubic feet of captured Japanese ordnance, and returned to Pearl Harbor (8–17 February). Fifty-one officers and 248 enlisted men boarded the warship, and she loaded 37 Hellcats, 16 USAAF Republic P-47 Thunderbolts, one Ventura, and a single Martin JM-1 [B-26] Marauder, and steamed to NAS Alameda (19–25 February). The ship’s new duties brought with them fresh recruits, and Capt. Williamson welcomed the new men in The Big K, the ship’s newspaper, on 15 February 1945:

“We hope that you will learn to love this ship and that you will share with us our pride in her accomplishments…”

“We who fought the ship against the best the [Japanese] had to offer on 25 October 1944, know that cooperation and teamwork backed by training and devotion to duty can bring triumph in the face of tremendous odds.”

The ship’s company did not have a moment to savor their liberty as another 81 officers and 87 enlisted men walked up the gangway, and she brought on board 79 USAAF North American P-51 Mustangs and 7,166 cubic feet of aircraft spare parts, slipped back under the Golden Gate Bridge and returned to Pearl Harbor (28 February–6 March 1945). Designated TU 19.9.12, the carrier then (7–17 March) transported her men and cargo to Guam. Kalinin Bay broke the monotony of the ferry voyages by a brief (18–20 March) interlude of flight operations for Carrier Air Group 99 to the west of Guam, but heavy seas slammed into the ship under what her historian laconically described as “exciting circumstances” while she tallied 202 deck landings before returning to harbor.

She next (22–31 March 1945) embarked two officers, 25 enlisted men, and three Army civilian employees, and loaded two 16 Hellcats, four FM-2s, USMC Vought F4U Corsairs, five TBMs, six Helldivers, and 87 aircraft engines and made for Hawaiian waters. At Pearl Harbor, Kalinin Bay followed an increasingly familiar pattern by embarking 35 officers and 253 sailors, and loading 19 Hellcats, one Ventura, a single Duck, and 433 cubic feet of miscellaneous cargo, and pushing on as TU 19.9.13 to Pier 2 at NAS Alameda (1–7 April). The carrier then accomplished a routine overhaul and voyage repairs at United Engineering Co., Ltd., of Oakland, Calif., (9–19 April) following which she returned to Alameda.

Kalinin Bay next (21–27 April 1945) transported 50 officers, 30 enlisted men, 48 USAAF Thunderbolts, 1,135 cubic feet of general Army cargo, and 720 cubic feet of U.S. mail from Alameda to Pearl Harbor. Designated TU 19.9.7, the ship sailed with three officers, 36 enlisted men, the 48 Thunderbolts, and 1,173 cubic feet of general Army cargo to Eniwetok (28 April–5 May). The next day the ship swung around and, carrying one officer, seven enlisted men, and 600 cubic feet of U.S. mail, cleared the atoll and sailed back to Pearl Harbor (6–12 May). While Kalinin Bay lay at Oahu, 27 officers and 155 enlisted men boarded the ship as passengers, and she loaded three 16 FM-2s, USMC FG-1s, 15 TBMs, and 25,710 cubic feet of aircraft engines, and, once again as TU 19.1.13, turned eastward for San Diego (14–20 May).

Ninety-five commissioned and 72 enlisted passengers then boarded the carrier, and she loaded 20 USMC FG-1Ds and 36 F4Us, and 1,636 cubic feet of aviation spare parts, and steamed to Pearl Harbor (24–30 May). Designated TU 19.9.17, Kalinin Bay bought on board 71 officers, 219 enlisted men, six F6Fs, 14 FM-2s, 17 TBMs, 75 aircraft engines, and 1,202 cubic feet of miscellaneous cargo, turned around and plowed through the eastern Pacific back to San Diego (1–8 June).

The ship and her battled-tested crew enjoyed no respite from the grueling pace as another 32 officers boarded, and she loaded on board 20 FM-2s, 20 USMC FGs, five SB2Cs, five North American SNJ Texans, ten Culver TD2C-1 drones, and 1,231 cubic feet of miscellaneous cargo, and chartered a course for Pearl Harbor (12–18 June). Transporting 83 officers, 44 enlisted men, six personnel boats, 20 USMC FGs, 20 FM-2s, five SB2Cs, ten TBMs, five SNJs, and 3,316 cubic feet of miscellaneous gear as TU 19.9.19, Kalinin Bay then (19–29 June) turned her prow toward Guam. The vessel disembarked the passengers and unloaded the cargo at that island.

She cleared Guam carrying 166 officers, 108 enlisted men, 45 F6Fs, five USMC F4Us, and 462 bags of U.S. mail, and celebrated Independence Day at sea on the return voyage to Pearl Harbor (1–11 July). Some 165 commissioned and 112 enlisted passengers boarded Kalinin Bay for the swift trip to San Diego (12–19 July), who shared their cruise with a load of 19 marine F4Us, five FM-2s, four SB2Cs, a single TBM, and one Lockheed R50-5 Lodestar. The ship took a needed break from the ferrying to undergo an overhaul and voyage repairs at Naval Repair Base San Diego (20 July–5 August). The carrier made her trial runs and returned to NAS San Diego.

Kalinin Bay resumed her arduous but necessary ferry voyages to support the war effort and cleared San Diego carrying 49 officers, 250 enlisted men, nine F6Fs, seven SB2Cs, and 40 TBMs, and steamed to Pearl Harbor (9–15 August 1945). The ship in the meanwhile heard the exhilarating announcement of the Japanese agreement to surrender. Designated TU 19.9.18, she embarked 57 officer and 442 enlisted passengers and sailed back to San Diego (21–28 August). There, 44 officer and 222 enlisted passengers boarded the carrier, and she loaded 15 Grumman F7F Tigercats and 20,228 cubic feet of cargo, and chartered westerly courses to Pearl Harbor (2–8 September).

The following day on 9 September 1945, Kalinin Bay learned that she was to participate in what became Operation Magic Carpet—the return of veterans from the war zones by ships and aircraft. The ship shifted to TG 16.12, Rear Adm. Henry S. Kendall, ComCarDiv 24, to bring the men home from what she termed “the forward area.” Alterations to the ship to enable her to complete the task included installing 704 bunks on the hangar deck. Designated TU 16.12.3, Kalinin Bay moved to clear Pearl Harbor and steer for Philippine waters on 12 September, but tank landing craft LCT-1456 collided with her in the channel. Neither vessel reported casualties, but the collision caused some damage to Kalinin Bay’s Nos 1 and 5 sponsons about ten feet above the water line, and the ship returned to port and completed repairs.

Newly repaired, Kalinin Bay resumed her journey transporting 108 commissioned and enlisted passengers westbound and reached Guiuan Roadstead, Samar (15–28 September). The following day, the ship proceeded to Tacloban and pumped 130,197 gallons of fuel on board to ensure that she could complete the return voyage in one segment—a telling revelation of the amount of fuel she consumed in normal steaming. The escort carrier swung around and returned to Guiuan Roadstead on the 30th. Ninety-seven officers and 957 enlisted men boarded Kalinin Bay there for their voyage home, and the ship brought her embarked veterans first to Pearl Harbor, where an additional 24 officers and 25 enlisted men boarded, and from there on to NAS Alameda (1–19 October). Signs of “Well Done” and “Welcome Home” on the surrounding hills greeted the ship as she slid beneath the Golden Gate Bridge into the bay and disembarked her passengers at the naval air station, and then moved on to Naval Supply Depot Oakland.