South Dakota I (Armored Cruiser No. 9)

1902-1930

North Dakota and South Dakota both attained their admittance to the Union on 2 November 1889. South Dakota yielded the state’s place to North Dakota because of its position in alphabetical order, and South Dakota entered the Union as the 40th state.

(Armored Cruiser No. 9: displacement 13,680; length 503'; beam 69'7"; draft 26'1"; speed 22 knots; complement 829; armament 4 8-inch, 14 6-inch, 18 3-inch, 12 3-pounders, 2 18-inch torpedo tubes (submerged); class Pennsylvania)

The first South Dakota (Armored Cruiser No. 9) was laid down on 30 September 1902 at the Union Iron Works, San Francisco, Calif.; sponsored by Grace Harreid, the daughter of Gov. Charles M. Herreid of South Dakota and the wife of Dean Lightner; was launched on 21 July 1904; and commissioned on 27 January 1908, Capt. James T. Smith in command.

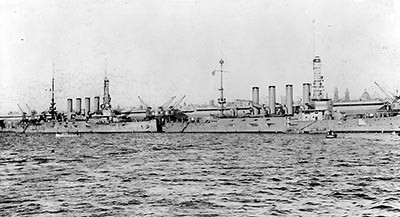

An act of Congress authorized South Dakota on 7 June 1900. The ship’s hull and machinery cost a contract total of $3,750,000. Her plant consisted of vertical triple expansion engines and 16 Babcock and Wilcox boilers, which powered two propellers. Four funnels, one cage mast, and one military mast provided a distinctive silhouette. One Type J submarine signal receiving set equipped the ship. Capt. Charles E. Fox reported on board as the ship’s General Inspector on 30 August 1907. The cruiser completed her preliminary acceptance on 19 November.

South Dakota began her shakedown on 3 March 1908. The ship sailed from San Francisco to Mexican waters, carrying out trials in Magdalena Bay from 8 to 10 March, and on 11 and 12 March off Isla Cedros, the ship reported her movements off the Anglicized spelling of Cerros Island, contributing to debate among international navigators concerning the designation of the island. She came about and visited San Diego, Calif. (13–24 March). South Dakota then made a brief voyage northward along the Californian coast and put into San Pedro through the end of the month, followed by a visit to Long Beach (1–5 April), returning to San Pedro on 5 and 6 April. On 8 and 9 April, the cruiser lay off the Mare Island Light, and then visited San Francisco. South Dakota attained a speed of 22.24 knots during her sea trials.

She then made for the Pacific Northwest to accomplish work associated with her shakedown, reaching Port Angeles, Wash., on 12 April 1908, and (13–23 April) entering drydock at Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Wash. South Dakota floated from the drydock and then anchored off Anacortes, Wash., from 23 to 25 April. Assigned to the Armored Cruiser Squadron, Pacific Fleet, South Dakota visited Seattle, Wash. (25–27 April). The ship returned to Puget Sound to participate in a reception for the Atlantic Fleet through 1 May. Following the reception, the cruiser completed her final acceptance trials off San Francisco through the end of May. South Dakota cruised off the west coast of the United States into August. She departed San Francisco in company with Tennessee (Armored Cruiser No. 10) on 24 August, arriving on 23 September at Pago Pago, Samoa.

South Dakota sailed easterly courses to operate in Central and South American waters in September. The ship came about to the westward to serve with the Armored Cruiser Squadron in the autumn of 1909. The ships of that squadron called at ports in the Admiralty Islands, Philippines, Japan, and China, before South Dakota returned to Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands, on 31 January 1910.

Nicaraguan Gen. Juan J. Estrada launched a rebellion against the country’s president, José S. Zelaya, in October 1909. Both men proclaimed liberal policies, but Zelaya repeatedly criticized the U.S. and openly embraced ties with the Germans and Japanese. The relations between Washington and Managua consequently deteriorated. Estrada rebelled in Bluefields, a gold mining and banana and rubber plantation town on the Mosquito Coast that contained large numbers of foreigners including Americans. Zelaya’s troops captured and executed a pair of American mercenaries who fought for the rebels. The murder of the two men, combined with the threat against Bluefields, compelled President William H. Taft to sever diplomatic relations with Zelaya. The Nicaraguan president resigned on 17 December 1909, and José Madriz, Zelaya’s protégé, assumed the post, but continued to fight the rebels.

The government employed an armed steamship to blockade the rebels at Bluefields. Estrada implored U.S. assistance, and Sailors and Marines landed from Dubuque (Gunboat No. 17) and Paducah (Gunboat No. 18) on 19 May 1910. The men established neutral zones to protect Americans trapped by the fighting and to restore order. The gunboats alternated between thwarting the steamer from shelling or blockading the rebels, and transporting Leathernecks from Panama to Bluefields. The Marines remained ashore until 4 September. A conservative mining executive named Adolfo Díaz replaced Zelaya and arranged favorable terms with the U.S.

South Dakota and Tennessee sailed with a Special Service Squadron off the Atlantic coast of South America in February 1910. South Dakota took part in the Argentine Centennial. The ship returned to the Pacific late in the year, and then steamed in Mexican waters.

Following South Dakota’s departure, Tacoma (Cruiser No. 18) prevented converted yacht Hornet from participating in a revolution in Honduras in January 1911. The fighting continued, and Tacoma landed Bluejackets and Marines to protect Americans at Puerto Cortez on 1 February. The intervention defused the crisis, and the Honduran opponents met on board the cruiser and signed a peace treaty establishing a provisional government later that month.

South Dakota carried out drills with the Pacific Torpedo Fleet. Capt. Frank M. Bennett assumed command during this period. The ship completed repairs at Mare Island Navy Yard at Vallejo, Calif. (1 July to 30 September 1911). She coaled off the Mare Island Light through 3 October, and then sailed for San Pedro, reaching that port on 5 October. Through 9 October, South Dakota hove to off Santa Monica, Calif., and then returned to the Bay Area (10–16 October), taking part in ceremonies marking a visit to San Francisco by President Taft. The ship returned to southern Californian waters through Thanksgiving, alternatively carrying out gunnery practice and drills off Coronado, San Diego, Long Beach, and San Pedro, and visiting those ports for brief periods of liberty. In addition, she took part in a review of the Pacific Fleet (1–4 November), and coaled on 14 and 15 November in preparation for a cruise to the Orient.

South Dakota sailed with the Armored Cruiser Squadron from San Francisco to the Hawaiian Islands on 28 November 1911. The ship hove to off Honolulu, Oahu (3 and 4 December), coaled on 4 and 5 December, and sailed off Honolulu with the Pacific Fleet through 12 December. A port call at Hilo, Hawaii, provided crewmen the unique opportunity to visit a volcano (13–17 December). South Dakota spent the remainder of the year anchored off Honolulu.

The ship coaled off Honolulu (13–29 January 1912), and held an admiral’s inspection (29 January–1 February). South Dakota maneuvered with the Pacific Fleet (5–8 February) and through 12 February coaled off Honolulu. South Dakota sailed in company with California (Armored Cruiser No. 6) and Colorado (Armored Cruiser No. 7) to Lahaina Roads off Maui, Territory of Hawaii, on 12 and 13 February, and on 13 and 14 February hove to off Kealakekua on the main island of Hawaii. The ships then rounded the island to Hilo, where shore parties again visited a volcano (15–18 February). South Dakota returned to Honolulu and coaled (20 February–4 March). Through 16 March, the ship maneuvered with the Pacific Fleet, and then coaled and took on stores in preparation for continuing her cruise to the Far East.

South Dakota steamed from Hawaiian waters to Apra, Guam in the Ladrone Islands (Marianas) from 18 March to 2 April 1912. The ship steered westerly courses and reached Olongapo at Subic Bay, Luzon, Philippines, on 8 and 9 April. Filipino insurrectos (insurgents) continued to resist U.S. attempts to crush their insurrection, the predominantly Moslem and fiercely independent Moros of the south proving especially truculent. Pampanga (Gunboat No. 39) hove to off the island of Semut near Basilan on 24 September 1911. A landing party captured Mundang, and five Sailors subsequently received the Medal of Honor for their bravery while fighting their way through the hotly contested village.

South Dakota thus arrived in the area at a turbulent time, and she patrolled Philippine waters with the Armored Cruiser Squadron. The ship coaled at Cavite Island in Manila Bay, Luzon, on 9 and 10 April, from 11 to 13 April carried out a torpedo defense drill in the bay, and entered drydock for repairs at Olongapo (13 April–2 May). She coaled at Cavite from 2 to 4 May, and during the following two weeks, alternatively conducted runs preliminary to target practice and liberty calls to Manila. South Dakota held battle, division, and torpedo defense practice at Olongapo (17–24 May), and on 24 and 25 May carried out night experimental practice at Cavite. The ship set liberty routine through the first week of June, broken only on 31 May by a preliminary speed trial. She conducted an endurance trial on 4 and 5 June, and through 21 June completed repairs at Olongapo. The cruiser then returned to Manila (21–23 June), and through 26 June operated as a target ship for submarine flotilla practice.

The Chinese Revolution threatened Americans living within China. Marines reinforced the legation guards at Peking (Beijing) in October 1911, and transport Rainbow landed additional Marines at Woosung near Shanghai on 31 October. Protected cruiser Albany and Rainbow deployed 24 Marines to guard the cable station at Shanghai (4–14 November). On 24 November, Saratoga (Armored Cruiser No. 2) sailed from Shanghai to Taku (Tagu), China, where she landed Marines to protect American missionaries. Ships disembarked further shore parties at a number of Chinese ports during the succeeding weeks.

South Dakota supported these operations during her voyage home to the United States, steaming an indirect route across the Pacific Rim for her return. The ship sailed from Manila Bay to Woosung (26–30 June 1912). On 6 July, she put to sea and sailed northerly courses to Tsingtao (Qingdao), reaching that port on 8 July. Six days later, the cruiser made for Japanese waters, arriving at Yokohama, Honshū, on 17 July. South Dakota sailed from Yokohama on 24 July, and on 4 August reached Honolulu. She set out two days later, reaching San Francisco on 15 August.

The following day through 21 December, she accomplished repairs at Mare Island Navy Yard. Capt. David V.H. Allen relieved Capt. Bennett as the commanding officer on 17 December. The ship departed the yard and coaled at California City on 21 and 22 December, and then through the end of the year called at San Francisco. Capt. Charles P. Plunkett relieved Capt. Allen as the commanding officer on 6 January 1913. The ship carried out target practice, a torpedo defense drill, night practice, and drills with submarines off Coronado and San Diego (10 January–10 February).

Revolution tore Mexico apart in 1910. Wealthy landowners exploited impoverished peons (peasants), and Francisco I. Madero, an opposition leader, returned from exile in the U.S. and led a revolt against the country’s president, Gen. Porfirio Diaz, on 20 November. Gen. Victoriano Huerta overthrew and subsequently assassinated Madero. Disparate groups including the Conventionalists, led by men like Emiliano Zapata and former cattle rustler Francisco Villa; and Constitutionalists such as Gen. Venustiano Carranza, fought across Mexico. The chaos endangered Americans caught in the midst of the war and pushed President Woodrow Wilson to call on warships to protect, and if necessary, to evacuate Americans.

South Dakota consequently made for Acapulco, Mexico, on 11 February 1913. The cruiser reached Acapulco on 15 February and coaled. The ship called on Mexican ports to demonstrate U.S. resolve, visiting Topolobampo (11–24 April), Mazatlán (25 and 26 April), and (27 April–2 May) returned to Topolobampo. During each of these visits, she maintained wireless communications to the north and to the south.

The ship returned to San Diego on 5 and 6 May 1913, and (8–19 May) called at San Francisco. South Dakota entered drydock for repairs and painting at Mare Island on 19 and 20 May, on 20 and 21 May coaled at Tiburon, Calif., and then visited San Francisco. She took part in Memorial Day commemorations at Santa Barbara, Calif. (28–31 May). Through 5 June the ship visited San Diego, and then participated in the dedication of a Memorial Day monument at San Pedro and a preliminary speed run from 5 to 7 June. Two days of standardization and endurance runs followed, and South Dakota completed target practice and bore sighting off Coronado and San Diego through the end of the month.

Capt. William M. Gilmer assumed command during this period. South Dakota took part in the Fourth of July celebrations at Ventura, Calif. (3–6 July). The ship returned to San Francisco but hove to off Sausalito on 9 July, and some of her crewmen landed and helped civilian firefighters battle a fire at Tamalpais, Calif. The cruiser coaled at Tiburon on 18 July, and from 20 to 23 July called at San Diego during a visit to that city by Secretary of the Navy (SecNav) Josephus Daniels. Crewmen practiced their small arms proficiency at a nearby range through 30 July, and the ship then returned to the Bay Area, coaling at Tiburon on 1 August.

The Mexican Revolution again drew South Dakota southward, and she relieved Pittsburgh (Armored Cruiser No. 4) at Guaymas, Mexico (10–21 August 1913). During the following weeks, the ship operated in Mexican waters, carrying out wireless tests at Puerto Refugio on 23 August, subcaliber gunnery practice in San Francisquito Bay on 24 August, and the next day firing torpedoes off San Juan Bentasta. South Dakota rendezvoused with California and operated off Guaymas (26 August to 2 October). Prior to her departure from Mexican waters, the ship coaled and then carried out subcaliber training. South Dakota sailed on 3 October, six days later reaching San Francisco.

She entered Mare Island Navy Yard for the installation of a new topmast (15–17 October). The ship participated in the Portolá celebrations, in honor of Spanish explorer Don Gaspar de Portolá Rovira’s (European) discovery of the bay in 1769, at San Francisco (17–27 October), and returned to Mare Island to replace her 8-inch gun sights (27–29 October). South Dakota coaled at California City on 29 October.

From 2 to 10 November, she visited San Pedro to take part in the "aqueduct celebrations," the public announcement of Federal approval of a program to bring water via an aqueduct from the Hetch Hetchy Valley of Yosemite National Park to the Bay Area. The cruiser then carried out periodic torpedo exercises and subcaliber and preliminary runs for target practice off San Pedro, San Diego, and Coronado through 22 November. South Dakota spent Thanksgiving and Christmas drydocked at Mare Island, and coaled at California City on 26 and 27 December. On 27 December South Dakota visited San Francisco, where she received a draft for the Fleet and then sailed for the Pacific Northwest. South Dakota joined the Reserve Force, Pacific Fleet, at Puget Sound Navy Yard on 30 December 1913.

Lt. Comdr. Ralph Earle anchored dispatch ship Dolphin in Tampico on 6 April 1914. Earle sent his paymaster and a boat ashore, but the Mexicans arrested the men because they landed in a “forbidden area,” parading them through the streets. The Mexicans incarcerated an orderly from Minnesota (Battleship No. 22) when he went ashore for the mail at Vera Cruz a few days later. Rear Adm. Henry T. Mayo, Commander Fourth Division, demanded a 21-gun salute in apology over the “Tampico Incident,” and President Wilson ordered the Atlantic Fleet to send an expedition on 14 April. Reinforcements to patrol along the Pacific coast included South Dakota, which detached from reserve on 17 April 1914.

The following day, President Wilson wired an ultimatum as the lead ships of the Atlantic Fleet arrived in Mexican waters. The Mexicans could salute the flag prior to 1800 the following day or suffer the consequences, they apologized and rendered the salute. Rumors circulated, however, that the Germans attempted to smuggle 250 machine guns, 20,000 rifles, and 15 million rounds of ammunition on board steamer Ypiranga into Vera Cruz. Wilson therefore directed Rear Adm. Charles J. Badger, Commander Atlantic Fleet, to seize the customhouse at Vera Cruz. On the morning of 19 April, U.S. Consul William W. Canada notified Gen. Gustavo Maas, who led the garrison at the port, of the planned landings to avoid bloodshed. Huerta ordered Maas to make a show of force to influence foreign opinion among the observers on board the ships in the outer harbor, which included British and French armored cruisers Essex and Condé, respectively, and Spanish gunboat Carlos V.

The Americans landed at Vera Cruz on 21 April 1914. Capt. William R. Rush, the skipper of Florida (Battleship No. 30), commanded the landing force. Maj. Smedley D. Butler led the Marines ashore, and Rear Adm. Frank F. Fletcher, Commander First Division, shifted his flag to transport Prairie to monitor the battle. Fletcher summarized the day’s fighting:

“Tuesday, in the face of an approaching norther [a cold gale] I landed Marines and Sailors from the battleships Utah and Florida and the transport Prairie and seized the Custom-house. The Mexican forces did not oppose our landing, but opened fire with rifle and artillery after our seizure of the Custom-house. The Prairie is shelling the Mexicans out of their positions. Desultory firing from housetops and in the streets continues. I hold the Custom-house and that section of the city in the vicinity of the wharves and the American Consulate. Casualties, four dead and twenty wounded.”

The Americans established blocking positions across the streets leading toward the Plaza de la Constitucion, the main square. The Mexicans turned several buildings into strongholds and snipers shot at the invaders from vantage points at the Benito Juarez lighthouse and Naval Academy, and from box cars and warehouses along the waterfront. Gunfire from the ships broke-up enemy troop concentrations, but the operations continued into the summer. The Americans also seized Ypiranga, temporarily cutting off Huerta from his supplies, but the arms on board eventually reached the general. The invaders also left behind valuable stores. Wilson shrewdly allowed the Constitutionalists to receive supplies, enabling them to snatch control from Heurta, who resigned on 17 July and fled into exile.

South Dakota meanwhile sailed southerly courses to California City, where she coaled on 21 April, and the following day loaded stores at San Francisco. The ship then made for Mexican waters, reaching Acapulco on 28 April. South Dakota patrolled off Mazatlan (16–23 May), and (24 May–5 June) off La Paz.

While the ship operated in Mexican waters, Secretary of the Navy Daniels issued General Order No. 99 on 1 June 1914. The order annulled article 826 of the Naval Instructions, effective on 1 July, by substituting it with the following instruction: “The use or introduction for drinking purposes of alcoholic liquors on board any naval vessel, or within any navy yard or station, is strictly prohibited, and commanding officers will be held responsible for the enforcement of this order.”

South Dakota returned to Mazatlan through the end of June. Following her cruise in Mexican waters, South Dakota steamed to the Hawaiian Islands in August 1914. She returned to Bremerton on 14 September and reverted to reserve status on 28 September. The armored cruiser became the flagship of the Reserve Force, Pacific Fleet, from 21 January 1915. Later in the year, she participated in the Panama-Pacific Exposition, and then steamed in Mexican waters. Milwaukee (Cruiser No. 21) relieved South Dakota in Mexican waters on 5 February 1916. South Dakota completed repairs and an overhaul at Puget Sound Navy Yard from November 1916 until 5 April 1917.

On 5 April 1917, South Dakota was again placed in full commission with the U.S. entry into World War I—President Wilson declared war on the German Empire the following day. On 11 April, Allied leaders conferred at the Navy’s General Board in Washington, D.C. Secretary of the Navy Daniels, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, CNO William S. Benson, Adm. Henry T. Mayo, Commander-in-Chief Atlantic Fleet, Adm. Henry B. Wilson, Commander Patrol Force, and members of their staffs and the General Board conferred with their Allied counterparts, including British (Acting) Vice Adm. Montague E. Browning, RN, Commander-in-Chief North America and West Indies Station, and his French counterpart, Rear Adm. R.A. Grasset, concerning the deployment of U.S. naval forces. The conferees agreed upon ten points, five of which subsequently impacted South Dakota’s operations.

1. They assigned the USN to patrol the Atlantic coast from Canadian to South American waters for three reasons:

A. To protect shipping for the Allied armies, including food for their civilians, and Mexican oil for their economic and military use.

B. To protect against the expected U-boat attacks—these planners feared that the Germans intended to establish (or already had established) secret submarine bases to facilitate their attacks against ships sailing in these waters.

C. Readiness to destroy German commerce raiders.

2. To prepare squadrons to operate against raiders in either the North or South Atlantic. The British and French conferees emphasized the plans concerning these squadrons (see C above) because enemy raiders had disrupted Allied shipping during the war to date.

5. The deployment of U.S. vessels to protect nitrite shipments from Chilean waters—vital for munitions manufacture.

6. To continue the deployment of the Asiatic Fleet.

10. To dispatch railway material via armed naval transports to French ports.

South Dakota shifted to the Atlantic to take part in these operations, departing Bremerton on 12 April and reaching San Francisco three days later. She underwent urgent repairs and loaded stores at Mare Island. During the ship’s two weeks at Mare Island, the yard workers installed a radio set. During this time frame, Capt. Lucius A. Bostwick assumed command.

South Dakota departed Mare Island for San Diego, Calif., and sailed from San Diego on 7 May 1917. She hove to off San José, Guatemala. Adm. William B. Caperton, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, and Capt. Bostwick called on the city of Guatemala. South Dakota reached Balboa, Canal Zone, on 21 May 1917. On 25 May, the ship passed through the Panama Canal, and coaled and took on supplies and provisions at Cristóbal, near Colón. She rendezvoused with Frederick (Armored Cruiser No. 8), Pittsburgh, and Pueblo (Armored Cruiser No. 7) at Colón. The trio of cruisers sailed from Colón on 29 May, holding drills, exercises, and sub-caliber practice while proceeding to the South Atlantic for patrol duty from Brazilian ports. They arrived off Bahia, Brazil, on 14 June. The squadron was to prevent German and Austro-Hungarian ships interned at Bahia from escaping into the Atlantic to operate as blockade runners or commerce raiders. South Dakota coaled from Nereus (Fuel Ship No. 10).

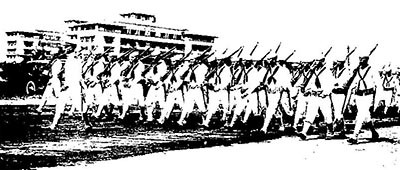

Pittsburgh, Pueblo, and South Dakota sailed from Bahia on 20 June 1917, reaching Rio de Janeiro two days later. While South Dakota visited Rio de Janeiro, she received coal from Nereus and ammunition and stores from Glacier (Store Ship No. 4). The ships called on the port to celebrate U.S. Independence Day, and held full dress on 4 July. Brazilian President Venceslau Brás [Pereira Gomes] visited Pittsburgh at 1300, and fifteen minutes later, South Dakota landed the ships battalion to parade as infantry through the streets of the city. British, French, and Brazilian forces also landed and took part in the festivities. South Dakota recorded that the large crowds of onlookers displayed “great enthusiasm” during the celebration.

Frederick, which had reached Rio de Janeiro in the interim, Pittsburgh, Pueblo, and South Dakota sailed on 6 July 1917, four days later arriving at Montevideo, Uruguay. The squadron sailed from Uruguayan waters on 23 July. The following day, a composite Argentinean division of three cruisers and four torpedo boats met the U.S. ships and escorted them into Buenos Aires. South Dakota recorded that the Argentineans provided a “very cordial” welcome during multiple excursions, dinners, and theater parties. The ships sailed from Buenos Aires on 1 August, called on Montevideo, and returned to Rio de Janeiro on 6 August. South Dakota loaded stores and fresh provisions from Glacier.

Frederick and South Dakota stood out of Rio de Janeiro and proceeded toward Bahia on 9 August 1917. The ships sailed in accordance with Campaign Order No. 1, designating them as the Northern Patrol Force. These orders directed the two armored cruisers to alternate their patrols to capture or sink enemy vessels north of Bahia as far as Ilha Fernando de Noronha and east to 20° W. One of the vessels was to steam at sea for a patrol of 14 days, cruising at ten knots during daylight and five knots at nighttime. The other cruiser was to remain at Todos os Santos, a bay at Bahia, overhauling during the first seven days, and then standing by for the second seven days. Pittsburgh and Pueblo patrolled from Rio de Janeiro eastward to cover the trade lanes between that city and Bahia.

The first 24 hours inaugurated the patrols with a dramatic confrontation. German commerce raider Seadler wreaked havoc with Allied shipping during this period. Formerly U.S. full-rigged ship Pass-of-Balmaha, she proved successful as a raider in large measure because of her sailing rig, which repeatedly enabled Seadler to surprise her victims. The raider prowled in South American waters prior to the arrival of South Dakota but then temporarily disappeared from Allied intelligence. While proceeding toward Bahia on 10 August 1917, South Dakota sighted a full rigged ship on the starboard bow. The vessel resembled descriptions of Seadler, and the cruiser intercepted the suspected raider. A boarding party inspected the ship but discovered Norwegian vessel Sandpigen, bound with a load of coal from Philadelphia, Pa., to Santos, Brazil. In April 1917, Seadler rounded Cape Horn and hunted her prey in the Pacific. She anchored at Mopeha in the Society Islands on 31 July. Seadler wrecked on a reef there on 2 August.

South Dakota returned to Bahia on 12 August 1917, and continued her patrols into the autumn. The armored cruiser stopped, boarded, and searched a number of suspicious vessels during these patrols, but without results. Adm. Caperton shifted his flag from Pittsburgh to South Dakota on 21 September, when Pittsburgh sailed for a cruise. Caperton returned to Pittsburgh on 1 October. On 14 October, Frederick, Pittsburgh, Pueblo, and South Dakota sailed from Rio de Janeiro. The ships carried out battle practice and maneuvers en route to Montevideo, arriving on 18 October.

South Dakota received orders detaching her from duty with the Pacific Fleet and directing her to rendezvous with Division Two, Cruiser Force Atlantic Fleet, at New York, on 2 November 1917. Prior to her departure, the ship received drafts of men from Frederick, Glacier, Pittsburgh, and Pueblo for transfer to the U.S. South Dakota reached Port Castries at St. Lucia, British West Indies, on 18 November. While the ship coaled, Raleigh (Protected Cruiser No. 8) arrived and coaled, following her voyage from Hampton Roads, Va., via NS Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, to Rio de Janeiro. South Dakota sailed from Port Castries the following day.

The ship received orders to proceed to Hampton Roads on 22 November 1917. Two days later, she stood into Hampton Roads and began coaling. South Dakota also loaded thousands of pieces of lumber for delivery to cruisers at New York. The ship sailed on 26 November, and the following day reached New York. South Dakota completed slight repairs and a short overhaul at New York Navy Yard from 5 to 15 December. She carried out painting and cleaned her bottom, and loaded stores and provisions. South Dakota received orders to remove her 6-inch guns from the gun deck on 12 December, and accomplished the work within two days.

She sailed from New York on 15 December 1917, and then conducted firing practice in the Southern Drill Grounds in Chesapeake Bay. The ship coaled at Hampton Roads, and reached the North River Anchorage at New York on Christmas Eve. Generally speaking, the larger and faster cruisers of Cruiser Squadron One escorted troop convoys, while the smaller vessels of Cruiser Squadron Two escorted cargo convoys. Frederick, Pueblo, San Diego (Armored Cruiser No. 6), and South Dakota initially comprised Division Two of Cruiser Squadron One.

South Dakota commenced operations supporting troop convoys to French waters during the New Year. The ship received orders to proceed to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to escort “fast liner convoys” on 2 January 1918, ocean liners pressed into service as transports comprised some of the ships that South Dakota escorted during World War I. She sailed the following day, and reached Halifax on 5 January. On 12 January, South Dakota escorted her first such convoy from Halifax, bound for Liverpool, England. German U-boats failed to attack the convoy, and South Dakota came about at the mid-Atlantic rendezvous point on 21 January, returning to Halifax on 29 January.

The armored cruiser then escorted a convoy consisting of predominantly British ships: Adriatic, Cassandra, Cherryleaf, Corsican, Glaucus, Messanobic, Ordina, Scandinavian, and Teutonic. The convoy sailed from Halifax on 5 February 1918, the following day rendezvousing with Grampian and Northland and French transport Canada. South Dakota came about in the mid-Atlantic on 13 February, while the other ships continued to Liverpool. Heavy seas plowed into South Dakota and at 1305 on 20 February, a large wave swept over the boat deck, knocking all the boats on the port boat deck from their cradles and damaging every boat. The cruiser returned to Halifax on 22 February.

Montana (Armored Cruiser No. 13) relieved South Dakota, which sailed from Halifax on 25 February 1918, two days later arriving at Portsmouth, N.H. The ship completed repairs and an overhaul at Portsmouth Navy Yard, from 28 February to 15 April. South Dakota sailed from Portsmouth on 15 April, and carried out target practice at Hampton Roads. She coaled and on 27 April anchored at New York.

South Dakota escorted Troop Convoy Group 32, consisting of U.S. ships Finland, Kroonland (Id. No. 1541), Manchuria (Id. No. 1633), Martha Washington (Id. No. 3019), and Powhatan (Id. No. 3013), from New York on 1 May 1918. Matsonia (Id. No. 1589) served as the flagship and rendezvoused with the convoy from Newport News, Va. South Dakota turned over the convoy to a screen of seven destroyers on 10 May and came about. The armored cruiser held target practice en route, and arrived at Hampton Roads on 18 May. The convoy continued to St. Nazaire, France. The cruiser refueled and sailed from Hampton Roads on 24 May, the following day arriving at New York.

The Western Escort, comprising South Dakota, Huntington (Armored Cruiser No. 5), and Fairfax (Destroyer No. 93) and Gregory (Destroyer No. 82), participated in the escort of Troop Convoy Group 45, consisting of: U.S. flagship President Grant (Id. No. 3014) and Nopatin (Id. No. 2195), French steamship Patria, and Italian steamship Re di Italia from New York; along with Pocahantas (Id. No. 3044) and Susquehanna (Id. No. 3016), and Italian steamships Caserta and Duca d’Aosta from Newport News. The ships gathered at New York and sailed on 23 June. President Grant dropped out of the convoy and returned to New York, renewing her voyage to French waters with another convoy on 30 June. Overnight on 2 July, a German U-boat torpedoed transport Covington in that convoy, which sank with a loss of six men. The destroyers of the Eastern Escort meanwhile joined the remaining ships of Troop Convoy Group 45 on 3 July, and South Dakota came about.

South Dakota’s lookouts sighted what the ship reported as “a suspicious disturbance” in the water ahead on the starboard bow, at 1920 on 4 July 1918. Watchstanders spotted “a dark object,” but could not confirm that an enemy submarine stalked the ship. Owing to a shortage of coal, South Dakota changed course for Newport, R.I., arriving at the Naval Coal Depot at Melville, R.I., on 11 July. The ship coaled and sailed on 12 July, the next day reaching Hampton Roads. She refueled and then made for New York on 14 July, arriving the following day.

The Western Escort, consisting of South Dakota, Hopkins (Destroyer No. 6), Mayrant (Destroyer No. 31), and Walke (Destroyer No. 34), shepherded Troop Convoy Group 51 from New York on 18 July 1918. American steamships George Washington (Id. No. 3018), Antigone (Id. No. 3007), De Kalb (Id. No. 3010), Lenape (Id. No. 2700), and Rijndam (Id. No. 2505), together with Italian steamship Regina di Italia and British cargo ship Ophir, sailed with the group. Huntington escorted Pastores, Princess Matoika (Id. No. 2290), and Wilhelmina (Id. No. 2168), British steamship Czaritza, and Italian steamship Dante Aligheri from Newport News, and they rendezvoused with the convoy. George Washington served as the flagship, she had formerly sailed as a German passenger liner of the same name, operated by the North Germany Lloyd Line but seized by the U.S. The following day, German submarine U-156 sank San Diego off Fire Island, Long Island. South Dakota and San Diego had often operated together.

South Dakota’s lookouts sighted a suspicious disturbance in the water on the starboard bow at 1025 on 21 July. The ship fired four rounds from her No. 1 6-inch gun at the apparent U-boat, but the target disappeared. South Dakota rendezvoused with eight destroyers of the Eastern Escort and came about on 28 July, returning to Hampton Roads on 6 August. George Washington and De Kalb subsequently detached and made for Brest, France, while the balance of the convoy continued to St. Nazaire.

The armored cruiser coaled and stood out the same day, taking charge of Troop Convoy Group 55. Hull (Destroyer No. 7) joined South Dakota escorting the convoy, consisting of Huron (Id. No. 1408), Madawaska (Id. No. 3011), and Zeelandia (Id. No. 2507), British steamship Kursk, and Italian steamship Duca D’Abruzzi. That evening, the Italians reported a dirigible in need of help, and South Dakota dispatched Hull to investigate. The destroyer in turn directed submarine chaser SC-201 to the assistance of the airship at 2345. South Dakota sighted and joined the New York section of the convoy, escorted by Pueblo, on 7 August. She turned over her charges and proceeded toward New York, arriving at 1014 on 8 August.

A heavy squall of wind and rain lashed New York on 14 August 1918. French armored cruiser Condé grounded on the east bank of the river abreast of Grant’s Tomb. South Dakota sent a boat to the assistance of the French, and three tugs hauled the ship off undamaged. South Dakota accomplished minor hull repairs, work on her anchor and engine, bottom cleaning, and painting at the nearby Navy Yard from 16 to 23 August. The yard coaled the ship and installed Burney gear for protection against mines, two otters designed to tow underwater at the end of steel cables sheared off mines, setting them adrift to be destroyed by gunfire. She then anchored off St. George, Staten Island.

South Dakota and Rathburne (Destroyer No. 113) escorted Mercantile Convoy H x 46 (fast) on 23 August 1918. British steamship Alsatian served as the flagship of the convoy, which comprised Zeelandia, British steamships Adriatic, Caronia, Cedric, Ceramic, Empress of Britain, Princess Juliana, and Pyrrhus, and French steamships Chicago and Lorraine. Preble (Destroyer No. 12), Bailey (Coast Torpedo Boat No. 8), two groups of submarine chasers, kite balloons, and planes escorted the ships from New York until they cleared the swept channel.

South Dakota opened fire on a suspicious looking disturbance about 1,500 yards on the starboard beam, at 1252 on 25 August. The ship fired 17 rounds before the disturbance vanished. The ship came about on 2 September, and returned to Hampton Roads on 10 September. Chicago and Lorraine later detached and sailed to Bordeaux, France, and the remaining ships made for Liverpool, England. The cruiser coaled and then carried out target practice at Tangier Sound, Chesapeake Bay, returning to New York on 15 September. Capt. John M. Luby relieved Capt. Bostwick as the commanding officer of South Dakota on 17 September.

At 1915 on 21 September 1918, South Dakota received instructions from Commander, Cruiser and Transport Force, to proceed to sea soon as possible to assist steamship Maine, which lost three blades of her propeller, dropping her maximum speed to three knots. The cruiser began unmooring at 0110 on 22 September, but a fouled hawse delayed her sortie until 0525. South Dakota reached Maine at 1235, and stood by her during the afternoon watch, turning over the stricken steamship to Lamberton (Destroyer No. 119) at 1800. South Dakota then returned to New York.

South Dakota formed the principal Ocean Escort, and Michigan (Battleship No. 27) and Bell (Destroyer No. 95) the Western Escort, for Troop Convoy Group 70, consisting of De Kalb (the flagship), George Washington, and British steamships Armagh, Coronia, and Ulysses. The convoy sailed from New York on 30 September 1918. Israel (Destroyer No. 98) sailed independently from Philadelphia and joined the convoy.

Lookouts on board South Dakota sighted a suspicious object broad on the starboard bow about 1,000 yards distant, at 1107 on 1 October 1918. The cruiser fired at the target, which resembled a mine with contact horns. The ship did not sink the target, which passed between Coronia and Ulysses, the report did not specify whether from the current or as the ships steamed passed. The convoy rendezvoused with Dante Alighieri, the flagship of the second group;Czaritza, Fairfax, and Hull from Newport News at 1318 on that busy day.

During this period, the worldwide influenza epidemic caused an estimated fifty million deaths. Navy medical facilities treated 121,225 USN and USMC victims including 4,158 fatalities during 1918. “The morgues were packed almost to the ceiling with bodies stacked one on top of another,” Navy Nurse Josie Brown of Naval Hospital, Great Lakes, Ill., recalled. Influenza swept through the troops and crewmen crowded on board the ships of Troop Convoy Group 70 during the voyage, killing 40 people: 18 of the 4,500 soldiers, 125 nurses, and 150 crewmen on board George Washington; one of the 1,593 Marines on board De Kalb; four of the 1,886 soldiers on Armagh; one crewman and one of the 2,274 soldiers on Dante Alighieri; and 15 of the 3,922 soldiers and 217 other passengers on Coronia. None of the 1,296 soldiers on board Czaritza or the 2,529 men on Ulysses perished. The disease struck a total of 1,094 people: 30 on board De Kalb; 530 on George Washington; 88 on Armagh; 268 on Coronia; 52 on Czaritza; 63 on Dante Alighieri; and 63 on Ulysses.

The crowded berthing spaces favored contagion. Crewmembers consequently kept the soldiers and Marines in the open air as much as possible, and held boxing bouts and band concerts to sustain morale. Doctors and nurses strictly enforced regulations in regard to spraying noses and throats twice daily, and wearing gauze coverings over mouths and noses, except when eating. Whenever possible, each of the transports fitted out their medical departments to duplicate the facilities available at hospitals, consisting of a surgeon’s examining room, dispensary, laboratory, dental office, dressing room, operating room, special treatment room, sick bay, and isolation ward. In addition, several dispensaries and dressing stations established throughout each ship tended minor cases.

Vice Adm. Albert Gleaves, Commander Cruiser and Transport Force, reported that the computation of the final tabulations from all ships indicated that 8.8 percent of the troops transported during the epidemic through the end of the war became ill, and of those who suffered from influenza or pneumonia, 5.9 percent died. This gave an average Army death rate for the individual voyages of 5.7 percent per 1,000. The Navy sick rate reached 8.9 percent, and the Navy death rate 1.7 percent.

South Dakota turned over the convoy to the Eastern Escort at 1937 on 11 October 1918. The Eastern Escort comprised Conner (Destroyer No. 72) the senior ship, Burrows (Destroyer No. 29), Drayton (Destroyer No. 23), Ericsson (Destroyer No. 56), Jarvis (Destroyer No. 38), McDougal (Destroyer No. 54), Nicolson (Destroyer No. 52), O’Brien (Destroyer No. 51), Roe (Destroyer No. 24), and Warrington (Destroyer No. 30). The cruiser came about and reached Hampton Roads on 18 October.

The ship next escorted the Newport News Division of Troop Convoy Group 76 on 21 October 1918. The group comprised Martha Washington (the division flagship), Aeolus, and Italian steamship Duca D’Aosta. New Hampshire (Battleship No. 25) and Charleston (Cruiser No. 22) guarded the New York Division of the convoy from that port, consisting of Pocahontas (the convoy flagship) Comfort (Hospital Ship No. 3), Ophir, and Brazilian steamship Sobral. South Dakota came about at the junction point where the two divisions formed the convoy on 22 October, and the following day reached New York. The convoy continued to Brest.

South Dakota, Philip (Destroyer No. 76), and British steamship City of London escorted the 13 British ships of Mercantile Convoy HX-54 (fast) from New York on 27 October. South Dakota came about on 6 November. The Armistice ended World War I on 11 November, and the cruiser returned to Hampton Roads on 15 November. Allied ships transported a total of 2,079,880 American troops to Europe before the Armistice: 952,581 in U.S. vessels; 911,047 in U.S. naval transports; 1,006,987 in British ships; 68,246 in British-leased Italian vessels; and 52,066 in French, Italian, and other foreign ships. American ships embarked 46.25 percent of the troops; U.S. naval transports 43.75; British vessels 48.25; British-leased Italian ships 3 percent; and the others 2.5 percent. July 1918 marked the month of the largest number of troops transported: 306,350. Some 1,720,360 troops sailed under U.S. escort; 297,903 under British escort; and 61,617 under French escort. American ships escorted 82.75 percent of these vessels; the British 14.125 percent; and the French 3.125 percent. The Cruiser and Transport Force expanded to a fleet of 142 ships by the Armistice. The Navy also counted 453 cargo ships, with another 106 ready for entry into naval service.

South Dakota carried out target practice at Tangier Sound (17–22 November). On 25 November, the ship entered New York Navy Yard and began fitting out to enable her to embark troops returning from Europe. South Dakota sailed from Hampton Roads on 21 December 1918, arriving at Brest on New Year’s Day 1919.

Early in the New Year the ship embarked 16 army officers and 1,372 soldiers of the 56th Coast Artillery Regiment, 144 men of the 474th Aero Construction Squadron, of which but 33 were privates, and four naval officers and 29 sailors — a total of 1,571 passengers — at Brest and set out for home (5–18 January 1919). Two days out a northwesterly gale slammed into South Dakota, and at 1130 that morning, “the biggest wave I ever saw,” Cmdr. P.F. Caldwell, her executive officer, recalled, tore into the ship. “It tumbled in over the forecastle head and the wall of water swept over the upper bridge, where Capt. J. [John] M. Luby, our commander, and others [one of them being Lt. Frederick T. Montgomery, the officer of the deck], including myself, were in the wooden pilot house. The next moment I was with the others in a tangle of broken glass and lumber. The pilot house was destroyed and there were six of us badly cut and bruised.”

The battered ship returned to the United States, but heavy fog that morning compelled her to anchor temporarily at Tompkinsville, on Staten Island, N.Y. Col. William E. Wood, the chief of staff and uniformed head of Connecticut’s Police Reserve, led a delegation from Danbury, Conn., who welcomed the returning Connecticut National Guardsmen. Their band alternated with the ship’s band in playing popular airs while the women police reservists threw packages of chocolate, candies, and cigars on board to the doughboys and sailors. When the fog cleared the warship moored at Hoboken, N.J. Montana meanwhile embarked 1,361 army veterans, most of whom belonged to the 3rd and 4th Trench Mortar Battalions, and set out from Brest an hour later than South Dakota and reached Hoboken an hour after the latter passed the Hook. President Grant, with 4,891 men on board, set out on the same dates but steered a more southerly course than the two cruisers, and escaped much of the foul weather en route to Hoboken. French liner La Rochambeau carried 883 men of the 337th and 339th Field Artillery of the 88th Infantry Division, and 50 “casual” (traveling individually) officers. The gale pummeled La Rochambeau, however, and the ship wired the army authorities at Hoboken that she could not continue against the heavy seas and changed course for Halifax.

The armored cruiser put to sea from New York for Brest on 23 January 1919, but on 1 February she broke her port propeller shaft. The ship returned for repairs to Portsmouth Navy Yard, reaching the yard on 22 February. South Dakota sailed on 15 June, the same day reaching Boston, Mass. She stood out of Boston on 18 June, and on 28 June reached Brest. The ship embarked 66 army officers and 1,826 soldiers, a total of 1,892 returnees. South Dakota sailed on 9 July, and on 19 July reached Hoboken, N.J. During these two voyages with the Cruiser and Transport Force, the ship brought a total of 3,463 troops home.

The Russian Civil War swept through Siberia during this period. The Bolsheviks, known as ‘Reds,’ and a disparate mix of people loyal to the Romanovs, or at least opposed to the Reds, and known as the ‘Whites,’ fought across fronts measuring thousands of miles. The Allies felt betrayed by the Russian withdrawal from the war, and sought to recover huge stores of munitions they had shipped to support the Russians. In addition, the Japanese sought to annex Russian territory. The Allies therefore intervened in the fighting, the Japanese landing troops at Vladivostok, Siberia, on 30 December 1917. Further Allied expeditions included American Sailors from Olympia (Cruiser No. 6), and soldiers of the 339th Infantry Regiment and 310th Engineers, who landed at Archangelsk and Murmansk on the White Sea.

Nearly 70,000 former Austro-Hungarian soldiers of Czechoslovakian origin complicated the tangled politics. The Czech Legionnaires desired to return to their newly independent homeland. The Bolsheviks planned to disarm the Legionnaires, however, the émigrés learned of the plan and mutinied, seizing a section of the Trans-Siberian Railway in June 1918. The counterrevolutionary Adm. Aleksandr Kolchak cooperated with the Czech Legionnaires, and they collectively defeated the principal Bolshevik forces east of the Volga River. This victory enabled the Siberians to form an autonomous nation with their capital at Omsk. An estimated 12,000 Czech Legionnaires captured Vladivostok on the morning of 29 June 1918, but desultory firing continued into the afternoon. Adm. Austin M. Knight, Commander-in-Chief Asiatic Fleet, who broke his flag in Brooklyn (Cruiser No. 3), thus ordered Sailors and Marines to land and guard the U.S. consulate, and to act as part of a patrol force consisting of Czech Legionnaires, British Royal Marines, and Japanese and Chinese sailors. These men protected the USN radio station and the Russian navy yard, and restored order and prevented further destruction within the city.

The retreating Reds murdered Czar Nicholas II and his family at Ekaterinburg in July 1918, but Leon Trotsky (Leib D. Bronstein), the Bolshevik Commissar of War, then rallied his troops at Kazan on the Volga River and drove the Whites across Siberia. Adm. William L. Rodgers relieved Knight in command of the Asiatic Fleet in late 1918. Kolchak renewed his march the following spring, and the Bolsheviks only narrowly repulsed him in the spring of 1919. The fighting seesawed through the summer and into the autumn.

South Dakota underwent fitting out as a flagship for the Asiatic Fleet, and then shifted from the Cruiser and Transport Force on 20 July 1919. On 1 September, Rear Adm. Casey B. Morgan relieved Adm. Gleaves, and Gleaves hoisted his flag as Commander-in-Chief Asiatic Fleet in South Dakota at New York. Most of the experienced crewmen discharged from the Navy or transferred from the ship prior to her departure, and the crew consisted almost entirely of recruits. In addition, she embarked a draft of 400 recruits for other ships on the Asiatic Station.

The cruiser sailed from New York on 5 September 1919, passed through the Panama Canal, and visited the Galapagos Islands, Marquesas, Tahiti, and Pago Pago during her voyage to Philippine waters. Gleaves observed that the journey could prove “of great value as an alternative route to the Philippines.” He also noted that the ship’s interception of messages from USN radio stations indicated “a matter of considerable importance in times of war.” South Dakota reached Manila on 27 October.

Gleaves reported his disappointment in the “old and obsolete vessels” of the Asiatic Fleet, adding that all of the ships operated “short of compliment.” Upon his arrival, Albany completed repairs at Olongapo, and colliers and yard craft operated in Philippine waters. Elcano (Gunboat No. 38), Monocacy (River Gunboat No. 2), Palos (River Gunboat No. 1), Quiros (Gunboat No. 40), Samar (Gunboat No. 41), Villalobos (Gunboat No. 42), and Wilmington (Gunboat No. 8) comprised the Yangtze Patrol along that vast river of the Chinese heartland. Helena (Gunboat No. 9) and Pampanga (Gunboat No. 39) sailed as the South China Patrol on the Canton (Guangzhou) River. Vice Adm. Rodgers, Commander Division One, broke his flag in Brooklyn at Vladivostok, supported by station ship New Orleans (Cruiser No. 22).

The Bolsheviks continued to drive Kolchak’s demoralized forces across Siberia, capturing Omsk on 14 November 1919. Two days later, Brooklyn and New Orleans landed Sailors and Marines to assist in policing Vladivostok, a stray bullet wounding a man from New Orleans. Nearly 8,000 U.S. troops of the 8th Division and 27th and 31th Infantry Regiments under Maj. Gen. William S. Graves, USA, an estimated 40,000 Japanese soldiers, and thousands of Czech Legionnaires and British, French, and Italian troops at times filled the ensuing power vacuum by holding key positions along the Amur Railway, and along the Trans-Siberian Railroad from Vladivostok westward toward Lake Baikal. Refugees flooded the ports, and a typhus epidemic raged virtually unchecked without adequate medicinal supplies, the Allies had decided to withdraw from the Russian Civil War and curtailed their shipments of supplies to the Whites.

South Dakota completed repairs, and on 8 December 1919, Rodgers sailed on board Brooklyn from Vladivostok. Gleaves sailed from Shanghai and on 12 January 1920 reached Vladivostok. American troops concentrated at the port preliminary to their evacuation, and the first contingent embarked on board U.S. Army transport Sheridan and sailed for Manila on 25 January. Kolchak’s troops continued to desert, however, and Soviet partisans entered the outskirts of Vladivostok on 31 January. Lt. Gen. Sergei Rozanoff, who commanded the White garrison, sought asylum at the Japanese headquarters. South Dakota and Albany landed Sailors and Marines to restore order, and the Americans reinstated the Zemstvo (a council). Gleaves tersely reported that the “city became tranquil.” The Czechs betrayed Kolchak to the Bolsheviks, who executed the admiral at Irkutsk on 7 February.

Gleaves sailed on board South Dakota from Vladivostok on 12 March 1920, leaving Albany to maintain the U.S. naval presence in the city. South Dakota reached Japanese waters, coaling at Nagasaki, Kyūshū, and then visiting Kōbe and Yokohama, Honshū. The admiral reported that cordial relations marked his visits, but added without elaboration that the hosts extended “unusual courtesies” to their visitors. Graves and his staff sailed with the last of the American troops from Vladivostok for Manila on 2 April. Two days later, the Japanese disarmed the majority of the White troops in the city and the Maritime Provinces, claiming the necessity of the action to protect themselves from attacks by Russian bandits. Red and White partisans then clashed with the Japanese. The fighting occurred mostly in the countryside, because the partisans, of both factions, lacked the strength to oust the Japanese from their positions. Gleaves meanwhile attended an Imperial Garden Party at Tōkyō on 18 April, but the ongoing crisis compelled his return on board South Dakota to Vladivostok on 25 April.

The deployment of the armored cruiser enabled Gleaves to release Albany to carry out target practice, and to establish a summer base for U.S. ships at Chefoo (Yāntái), China. New Orleans returned to Vladivostok on 21 May, and South Dakota made for Yāntái. Gleaves reported that the skippers of the other two ships, Capt. William C. Watts of Albany, and Capt. Edgar B. Larimer of New Orleans, performed their arduous and exacting tasks with the multi-national cabals with “conspicuous ability and tact.” South Dakota reached Yāntái on 25 May, and Gleaves shifted his flag to general cargo ship General Alava, she served as a transport. The admiral then landed and traveled to Beijing to confer with U.S. Minister to China Charles R. Crane.

South Dakota was renamed Huron in honor of that city in South Dakota on 7 June 1920. The construction of the second South Dakota (Battleship No. 49) drove the decision, in order to free the name for the battleship.

South Dakota, Albany, New Orleans, light minelayer Rizal, and Destroyer Division 13 assembled at Yāntái during the latter part of May and early June. All of the ships completed short range battle practice and director practice, with the exception of Elliot (Destroyer No. 146) and Upshur (Destroyer No. 144), which reinforced the Yangtze Patrol during turmoil triggered by unpaid Chinese warlord soldiers. The Americans brought Battle Target Raft No. 18 from Manila for these exercises, but the raft lost keel and ballast and capsized. Sailors erected masts on the side of the raft, spread nets, and the ships continued to use the vessel as a target.

Huron illustrated a microcosm of the ships operating in the Orient when she reported to the Asiatic Fleet that she logged nine desertions, 16 summary courts martial, one deck court, 26 petty punishments, and 24 sick men requiring hospitalization from 1 July 1919 to 1 July 1920.

The ship carried out what she reported as a “diplomatic mission” at Tagu from 10 to 13 July. She returned to Chinwangtao (Qinhuangdao), a tiny port located in proximity to Tientsin (Tianjin) that served as a refueling and communications station for the Asiatic Fleet. Huron was redesignated CA-9 on 17 July 1920. She served in the Asiatic Fleet for the next seven years, operating in Philippine waters during the winter and out of Shanghai and Yāntái during the summer. The ship intermittently carried out target practice at Yāntái, from 4 August to 15 September 1920.

Seaman 2nd Class John J. Morrill of Huron led a detail of mess cooks consisting of Seaman 2nd Class James V. Arrington, Anton Huhn, David Matheson, and William H. Moore, and Fireman 3rd Class Edwin Blair to the forward flour hold to break out flour required in the bake shop, at 1400 on 7 August 1921. Prior to this date, Sailors had noted foul air in the hold on several occasions, but had not submitted a report to address the issue up the chain of command.

Matheson entered the compartment but an unknown gas, subsequently analyzed as carbon dioxide, overcame him and he fell unconscious. Morrill and Huhn assisted their fallen shipmate, only to drop to the deck from the noxious fumes. One of the mess cooks called out to the chief petty officer’s quarters, located directly above the hold, that the vapors overcame the men. He then rushed to the dispensary for help. Another mess cook reported to the Officer of the Deck, who immediately sent reinforcements. Chief Electrician’s Mate Harry Kramer and Chief Machinist’s Mate William Wacker heard the Sailor call out and went down into the hold. The fumes overcame Wacker, but Kramer stumbled from the compartment to the platform above.

Several chiefs, hospital corpsmen, and other Sailors arrived. Chief Machinist’s Mate Merton H. Mangold descended to the flour hold and attempted to tie a line around Wacker to pull him to safety. The carbon dioxide almost overcame Mangold but he escaped. Kramer and Chief Electrician Clarence A. Howell rigged a windsail to a discharge from the ventilating system and lowered the contrivance to circulate fresh air in the hold. Mangold determinedly returned to the compartment, having a line about his own body and another for use in hoisting the victims. Mangold secured a line to Wacker and then clambered aloft. Sailors drew Wacker up to the platform.

Chief Watertender Walter T. Foley climbed down, attached a line to Matheson, and assisted in drawing him from the hold. The fumes drove Foley from the compartment before he could fasten a line to a second man. Shipwright Frank C. Heckard went down, attached a line to Huhn, and assisted in hoisting him from the storeroom. Heckard returned to the compartment, attached a line to Morrill, and assisted in raising him to the deck above. The other crewmen then hoisted Heckard out of the storeroom. Huhn and Morrill died, but Sailors used artificial respiration to revive the other men. SecNav Edwin Denby issued letters of commendation to Foley, Heckard, Howell, Seaman 2nd Class Wesley A. Iler (who took part in the rescue), Kramer, Mangold, and Wacker. Investigators concluded that fermentation of damp flour generated the gas.

Huron continued to show the flag across China, visiting Qinhuangdao from 16 to 28 September 1920, Port Arthur (Lüshun), Manchuria, on 29 and 30 September, and Darien (Lüda) from 1 to 4 October. The ship returned to Yāntái through 6 October, and put into Qingdao (7–11 October), Shanghai (12–26 October), and Foochow (Fuzhou) from 28 to 30 October. Huron made her first visit to Formosa (Taiwan) when she stopped at Keelung on Halloween. She then returned to the Chinese mainland and visited Amoy (2–4 November), the following day Swatow, and Hong Kong (6–18 November). The cruiser celebrated Thanksgiving in Philippine waters and loaded supplies at Manila (20–29 November), and fired practice torpedoes at the Torpedo Range on 29 and 30 November. She then completed an overhaul and repairs at Olongapo through 21 January 1921.

The ship held liberty for her crew at Manila (21 January–23 February 1921), and carried out rehearsal runs at Mariveles on 23 and 24 January, before returning to Manila through 28 January. Huron carried out additional rehearsal runs at Subic Bay (28 February and 1 March), and (1–4 March) at Lingayen Gulf, before returning to Manila to enable crewmen to venture ashore for liberty (4–7 March). Further gunnery target practice at Olongapo (7–10 March), a brief respite at Manila (10–14 March), additional gunfire exercises at Olongapo (14–21 March), and another interlude at Manila (21 March–18 April) prepared the ship for her participation in joint Army and Navy maneuvers at Corregidor (18–20 April). Huron lay at Manila through 10 May. The ship then made for Chinese waters and Adm. Joseph Strauss, Commander in Chief Asiatic Fleet, inspected the cruiser at Shanghai on 13 May. Strauss reported to SecNav that “Huron, considering her age, is in very good material condition but owing to the difficulty of obtaining boiler parts her boiler casings are burning out and will have to be renewed shortly.”

A cholera epidemic broke out in Shanghai while Huron visited the city in September 1921. Shanghai consisted of districts divided demographically by the ethnic composition of their inhabitants, and the ship placed the Chinese neighborhoods and the Japanese Quarter out of bounds for crewmen, restricting the men’s liberty to the International Settlement. These strict measures prevented the spread of the epidemic amongst Europeans and Americans, and Huron did not report any cases of cholera on board. The cruiser took similar precautions during problems with malaria and dengue fever, which also prevented the spread of these diseases among the crew.

The ongoing fighting between rival Chinese warlords in the Beijing area threatened Americans and other foreigners living within Beijing and Tianjin in April 1922. United States Minister Jacob G. Schurman appealed to Adm. Strauss for a cruiser and 150 Marines to reinforce the Marine Legation Guard. Strauss promptly dispatched Albany from Shanghai to Qinhuangdao. Albany landed 100 Sailors and Marines that marched overland to reinforce the U.S. garrison at Beijing. Strauss then sailed from Manila on board Huron with two companies of Marines embarked.

Schurman requested an additional 375 soldiers from the Philippines, to raise the Army’s northern China garrison from the 15th Infantry Regiment to its authorized strength. Secretary of State Charles E. Hughes recommended against the additional reinforcements, largely because of Congressional opposition to weakening the garrison in the Philippines. Schurman countered by recommending the temporary augmentation of the soldiers with the Marines from Huron into a composite battalion. Strauss agreed and sent the Marines from Huron by tug to Tagu and thence to Tianjin. The fighting between the Chinese troops moved past the area, and stragglers did not stop to loot Beijing or Tianjin. The State Department opposed the further expansion of the forces in North China, explaining that the presence of the garrisons denoted U.S. resolve, but also noting the vulnerability of a thousand soldiers and Marines against tens of thousands of warlord troops. The men from Albany and Huron returned to their ships by the end of May. Huron reached Hankow (Wuhan) at one point in 1923.

An earthquake devastated the central Honshū area of Japan at 1158 on 1 September 1923. The earth split along the Sagami Trough fault, in the Kantō plain about 50 miles south of Tōkyō, sending shock waves that toppled buildings across Tōkyō and Yokohama. A tsunami reaching an estimated height of 33 feet at places smashed into the coast. A vast cloud of choking dust covered the area as thousands of buildings collapsed. Stoves and braziers overturned, igniting rice-paper screens and straw mats that spread fires among wooden and paper buildings. People fled the ensuing inferno toward the Sumida River, but the flames set wooden bridges ablaze. Other people fled into Tōkyō Bay, but nearly 100,000 tons of burning Imperial Japanese Navy fuel poured from burst storage tanks at the naval station at Yokosuka into the water. Rumors circulated of looting by Chinese and Korean residents and by leftists seeking anarchy. The government proclaimed martial law, and mobs armed with clubs and spears and supported by soldiers murdered impoverished Japanese (suspected of leftist sympathies) and foreigners and people who spoke Japanese with accents. Earthquake aftershocks added to the disaster, known as the "Great Kantō Earthquake," which killed an estimated 142,800 people and rendered another 1.9 million homeless.

International aid agencies assisted victims of the Kantō Earthquake. Jack Morgan, son of U.S. financier J. Pierpont Morgan, sponsored a $150 million loan program to support reconstruction efforts. The House of Morgan dispatched the firm’s partner Thomas Lamont to assess the damage. Additional foreign aid included a £25 million loan from the British firm of Morgan Grenfell. The distribution of this aid required tremendous resources, and included the American Relief Expedition.

Adm. Edwin A. Anderson, Jr., commanded the expedition and broke his flag in Huron. The flagship sailed from Yāntái on 3 September, and on 7 September arrived at Yokohama. The admiral held a conference on board Huron with all of the commanding officers of the naval and merchant ships in the harbor. Capt. Clark D. Stearns commanded the Advance Base, which assumed general charge of all of the relief work connected with Americans residing or traveling in Japan overtaken by the disaster. Stearns and his men controlled the initial distribution of supplies furnished by the Asiatic Fleet. Lt. Col. Ellis B. Miller, USMC, served as Stearns’ Chief of Staff, and Lt. Comdr. Earl W. Spencer, Jr., worked with the American nationals trapped in Japan. The expedition issued Order No. 1, directing that “Initiative is desired on part of all officers,” and dispatched a group to each of the two principally stricken cities.

Capt. Gatewood S. Lincoln commanded the Tōkyō Group. Lincoln and his staff contacted organizations and groups conducting relief of Americans ashore, and established first aid stations, hospitals, refugee camps, and soup kitchens. Lt. Comdr. Joel W. Bunkley commanded the Yokohama Group that carried out similar operations. Huron landed 12 officers and 264 enlisted men that formed the primary shore party that initially worked in the Yokohama Group.

The shore parties turned over the bulk of the available medical supplies to Japanese officials. They also furnished some to international humanitarian relief workers, to the U.S. Embassy in Tōkyō, and to the Relief Committee at Kōbe. The Sailors and Marines also organized and deployed to a Kōbe field hospital consisting of five medical officers, a dental officer, and seven hospital corpsmen, together with tents and equipment.

The expedition promulgated strict uniform standards to avoid incidents with the Japanese or with other countries that landed people to aid the victims. Officers wore uniforms identifying them as “American Naval or Marine officers.” Navy enlisted orderlies wore white with belts, and Marine orderlies served in khaki with belts. Beach Guards wore white with leggings and belts and carried night sticks. All other men wore whites or khakis as required, but enlisted men wore dungarees during working parties, but with U.S. Navy or U.S. Marine Corps stenciled for identification.

Huron usually signaled the Tōkyō Group via destroyer Stewart (DD-224), which relayed the flagship’s communications, and via other destroyers as available to the Yokohama Group. Lincoln and Bunkley controlled their respective groups’ signal lines from shore to city. Pekin (Beijing) Radio rendered excellent service to the expedition, and received the flagship’s arc over a distance of approximately 1,200 miles, despite atmospheric problems caused by the typhoon season. The volume of traffic proved burdensome and for several days the ship received messages totaling 8,000 to 10,000 words daily. The Washington Naval Conference further restricted communications, and the Beijing station could not forward press dispatches. In addition, the Los Baños distant control station in the Philippines could not read the flagship’s signals. The difficulties of maintaining local communications amidst the devastated infrastructure led to extensive use of visual signals when practicable.

United States Ambassador in Japan Cyrus E. Woods subsequently cabled: “I have been informed by the Foreign Office that food emergency has been met. Only problem remaining is question of distribution. This the Japanese with their organizing ability and their ability to recover from shock desire to handle themselves. It will gratify the American people to know that the prompt action of Admiral Anderson has had much to do with this. American Navy’s assistance thoroughly appreciated by the men in the street as well as the Japanese government. I wish to emphasize that in this critical emergency the first assistance from the outside world since the catastrophe was brought by our Asiatic Fleet.” Japanese Ambassador to the U.S. Hanihara Masanao later expressed his gratitude for Anderson’s “unflagging zeal and efficiency” that led to the “prompt and gallant assistance” that enabled the situation to be brought “well under control in a short time.”

Additional ships that participated in the relief efforts included the 38th, less Borie (DD-215), and 45th Destroyer Divisions, destroyer tender Black Hawk (AD-9), General Alava, oiler Pecos (AO-6), and Army transports Meigs and Merritt. Japanese Prime Minister Adm. Yamamoto Gonnohyōe received Adm. Anderson on 20 September. Huron sailed from Japanese waters on 21 September, and on 25 September reached Shanghai.

As the New Year of 1925 began, the Asiatic Fleet reported upon the inadequate communications facilities on board Huron, which rendered her unsatisfactory as a fleet flagship. Light cruiser Memphis (CL-13) relieved Pittsburgh (CA-4) on the European Station, enabling the latter to complete an overhaul at the New York Navy Yard. Pittsburgh subsequently relieved Huron. Pittsburgh proved a propitious relief because of her (relatively) spacious flag accommodations. In addition, the ship normally embarked up to 75 Marines.

Ordered home, Huron departed Manila on the last day of 1926 and arrived at the Puget Sound Navy Yard on 3 March 1927. She was decommissioned on 17 June 1927, and remained in reserve until struck from the Navy list on 15 November 1929. On 5 February 1930, the Navy awarded $69,110.60 for the sale of Huron, in accordance with the provisions of the London Treaty for the limitation and reduction of naval armament, for scrapping to Abe Goldberg and Co., Seattle, Wash.

Rewritten and expanded by Mark L. Evans

26 March 2015