Iowa II (Battleship No. 4)

1897–1923

Iowa was admitted to the Union as the 29th state on 28 December 1846, and derives its name from its original habitation by the Iowa (Ioway) people of the Sioux nation.

II

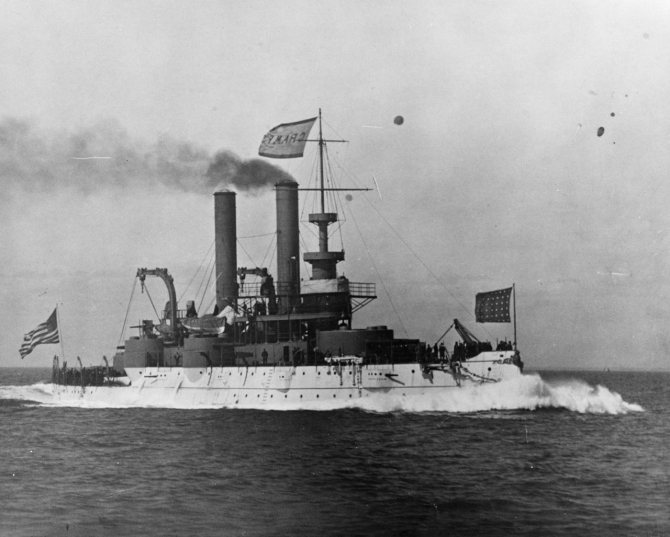

(Battleship No. 4: displacement 11,346; length 360'; beam 72'2"; draft 24'; speed 17.09 knots (trial); complement 505; armament 4 12-inch, 8 8-inch, 6 4-inch, 20 6-pounders, 4 1-pounder Hotchkiss, 4 Gatlings, 2 14.2-inch torpedo tubes)

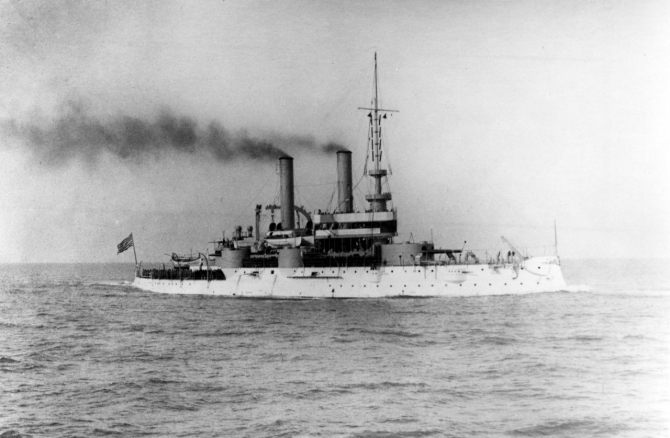

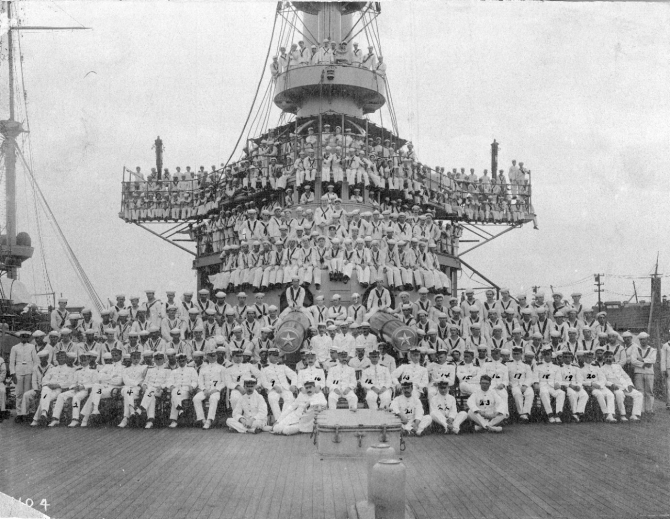

The second Iowa (Battleship No. 4) was laid down on 5 August 1893 at Philadelphia, Pa., by William Cramp & Sons Ship & Engine Building Co.; launched on 28 March 1896; sponsored by Miss M. L. Drake, daughter of Governor Francis M. Drake of Iowa; and commissioned on 16 June 1897, Capt. William T. Sampson in command.

Iowa sailed from League Island, Pa., for her shakedown off the Atlantic Coast on 13 July 1897. The ship visited Newport, R.I. (16 July–11 August); Provincetown, Mass. (12–14 August); Portland, Maine (16–23 August); and Bar Harbor, Maine (24–31 August). She then came about and put into three Virginia ports: Hampton Roads (12–16 and 19–27 September); Newport News (16–19 September); and Yorktown (27 September–4 October).

The battleship returned to New England waters and visited Provincetown (12–14 October) and Boston, Mass. (15–22 October). She then stopped at Tompkinsville, N.Y. (24–29 October), and rounded out the year by completing repairs at the New York Navy Yard (29 October 1897–5 January 1898). Iowa returned to Hampton Roads (5–12 and 14–16 January 1898) and Newport News (12–14 January). She then made for warmer waters and visited Key West, Fla. (23–24 January and 19 February–10 March), and the Dry Tortugas, Fla. (24 January–19 February and 10–12 March).

While Iowa had been in the process of joining the fleet, tensions elsewhere -- an insurrection had broken out in Cuba against the Spanish in 1895 – would have an impact upon her opertations. At 2140 on 15 February 1898, an explosion in the forward third of battleship Maine, anchored in Havana harbor, destroyed the ship, killing 266 men. The incident outraged Americans, who used the slogan “Remember the Maine!” to press for war against Spain, who many Americans suspected of planting a mine.

Capt. Sampson received an appointment to serve as President of the Board of Inquiry to investigate the loss of Maine, on 17 February 1898, and then to command the North Atlantic Squadron. Consequently, Capt. Robley D. Evans relieved Sampson as Iowa’s commanding officer on 24 March, while the ship lay at Key West (13–27 March). Two days later, Sampson relieved Rear Adm. Montgomery B. Sicard in command of the North Atlantic Squadron -- as acting rear admiral. Iowa visited the Dry Tortugas (27–29 March) and Key West (29 March–22 April) while she made ready to fight the Spanish.

President William McKinley, Jr., asked Congress for the authority to intervene in Cuba, on 11 April 1898, and eight days later, Congress authorized him to use force to expel the Spanish from the island. The President proclaimed a blockade of the Cuban coast from Havana to Cienfuegos on 22 April. Amidst preparations for war, the Navy formed a Flying Squadron, under the command of Acting Commodore Winfield S. Schley, to defend the East Coast from a Spanish attack. Sampson concentrated his ships at Key West, and upon receipt of the news of the blockade, headed for Cuban waters. The following day, his warships began blockading Cárdenas, Cienfuegos, Havana, Mariel, and Mátanzas. Iowa blockaded her sector through the end of the month (22 April–1 May), and then returned to Key West (2–3 May). On 25 April, Congress declared that a state of war had existed since 21 April.

Intelligence information reached the U.S. on 1 May 1898 that, on the previous day, a Spanish squadron under Rear Adm. Pascual Cervera y Topete, consisting of four cruisers and three torpedo boats, had sailed from São Vicente, Cape Verde Islands. Sampson surmised that Cervera was heading for Cuban waters to break the blockade and would put into Puerto Rico.

Sampson, meanwhile, sailed with New York (Armored Cruiser No. 2) from Key West to intercept the enemy, on 4 May. He rendezvoused with Indiana (Battleship No. 1), Iowa, and Detroit (Cruiser No. 10) off Havana, and subsequently with Amphitrite (Monitor No. 2) and Terror (Monitor No. 4), Montgomery (Cruiser No. 9), Porter (Torpedo boat No. 6), tug Wompatuck, and collier Niagara, and proceeded on easterly courses. Indiana experienced problems with her boilers, and in combination with the frequent breakdowns of the monitors, the ships proceeded slowly.

Dispatches reached Sampson when he reached a position off Cap Haitien on 7 May 1898, informing him that Cervera had put in to St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. The messages also cautioned Sampson on risking his ships during shore bombardment while the Spanish squadron remained operational.

Just before dawn on 12 May 1898, the U.S. ships arrived off San Juan, P.R., but discovered an empty harbor. A light breeze touched the air, and a long groundswell set to the southward. Iowa entered the firing line at 0515, and Evans sent the crewmen of the port secondary battery below, in the casemate. Two minutes later, she fired two shots from the 6-pounder on the starboard forward bridge and one round from the starboard 8-inch turret, at Castillo San Felipe del Morro (identified by the Americans simply as El Morro). After these ranging shots, the entire starboard battery opened fire. The ship passed over the firing line at a speed of between four and five knots until 0525, engaging the Spaniards from ranges varying from 2,300 to 1,100 yards. Sampson ordered Iowa to cease using her secondary guns and the gunners of the starboard battery lay below, within the casemate, at 0530. Iowa hauled offshore and stood slowly to the northwest. She turned again to the eastward, reentered the firing line, and led the column during two more runs, concentrating her fire at El Morro—though also firing “some shots” at the eastern battery during the third run. The smoke hanging about the battleship obscured her batteries and slowed their rate of fire.

The Spanish guns opened up in return and while Iowa steered northwest on the return course following her second run, an enemy 6- or 8-inch shell (estimated from the base plug and fragments found), apparently fired by the eastern battery, exploded at the after port skid frames, beneath the boats and abreast the after 8-inch turret. The fragments seriously wounded Private G. Merkle, USMC, causing a compound comminuted fracture of his right elbow, and Seaman J. Mitchell in his back, sixth intercostal space, and Apprentice Second Class R. C. Hill, inflicting a contused wound in his back. The blast damaged the ship’s first whaleboat, and the shell passed through the sailing launch, and made several holes in the stanchions, ventilators, galley funnels, and other deck fittings. A fragment struck the 6-pounder cage mount on the starboard after side of the forward bridge and jammed the training securing bolt and the gun pivot, though the gunners later repaired the damage. Other fragments damaged the joiner work on the bridge. Another round (or fragments) struck above the boat skids on the starboard side and slightly damaged the escape pipes and smokestacks.

While Iowa fired her final round from the after 12-inch turret, at about 15° on the starboard quarter, the unconsumed powder prisms from the blast of the discharge badly pitted the deck planking on the starboard quarter (indicating that the gun did not properly consume its powder charge). The blast tore the hatch plate from its bolts and threw it back toward the gun, clear of the hatch. Two of the holding-down bolts broke, and several of the lugs on the plate cracked. The plate emerged from the smoke slightly twisted. The deck beams, frames 82 and 83, abreast the cabin skylight hatch, starboard side, sprang out of line in the transverse sense. The bulkhead about the cabin doors between frames 79 and 83, starboard side, was torn from its hangers on the beams, and the rivets were sheared. In addition, the blast of the forward 12-inch gun, when trained forward, made sufficient play to the deck to damage the training-trolley circle of the starboard torpedo tube, the second time, Evans reported, that that had occurred. The blast effect of the forward 12-inch guns also smashed the partition forming the captain’s sea cabin in the pilot house.

Iowa completed her third run at 0725, having fired a total of 19 12-inch semi-armor-piercing rounds, and 18 8-inch, 46 4-inch, 48 6-pounder, and seven 1-pounder common shells. The Americans ineffectually bombarded the harbor fortifications for two hours, losing altogether Chief Yeoman George H. Ellis of Brooklyn (Armored Cruiser No. 3) killed and six men wounded.

The ships came about for Havana, where Sampson surmised that Cervera would make a course, but he received dispatches en route that revealed that Cervera had coaled at Curaçao, Netherlands West Indies (14–15 May 1898). Sampson was thus ordered to proceed “with all possible dispatch to Key West.” The Americans reached their destination on 18 May, and the following day the Spanish reached Santiago de Cuba unhindered.

The Navy, meanwhile, had dispatched Schley’s Flying Squadron to Key West as well. When Sampson returned to the station, he directed Schley to blockade Cienfuegos. Schley sailed initially with Massachusetts (Battleship No. 2), armored vessel [battleship] Texas, Brooklyn, and converted yacht Scorpion, breaking his flag in Brooklyn. Sampson pledged to send Iowa to reinforce the Flying Squadron once she finished coaling from the collier Saturn, and signaled her to “Stop coaling in time to reach Havana before dark.” Iowa thus sailed from Sand Key anchorage at Key West at 1115 on 20 May 1898, rendezvoused with the blockading force off Havana at 1840, then turned westward and started for Cienfuegos.

Iowa rendezvoused with the Flying Squadron off Cienfuegos and joined the column astern of New York during the afternoon watch on 22 May 1898. At 1807, New York signaled Iowa to “Increase distance at dark to 600 yards. Keep bright lookout, several gun vessels reported inside; the Dupont [Du Pont (Torpedo boat No. 7)] will patrol inside the squadron.” The following day, Castine (Gunboat No.6), converted yacht Hawk, and collier Merrimac joined the squadron, and Iowa coaled from Merrimac. During the afternoon watch on 23 May, Evans signaled Sampson: “News from Jamaica reports the Spanish fleet [sic] arrived at Santiago Thursday [19 May] and left Friday; think they are at Cienfuegos now, as I heard heavy guns firing on Saturday about 4.30 o’clock, 30 miles west from here. I interpreted it as a welcome to the fleet.”

Marblehead (Cruiser No. 11) reached the Flying Squadron during the forenoon watch on 24 May 1898, and Iowa coaled Du Pont. A long sea from the east-southeast, which Capt. Evans reported as “Squally and rainy,” lashed the ships as they steamed southward and eastward along the Cuban coast from Cienfuegos to Santiago (25–27 May). The battleship blockaded Santiago de Cuba, repeatedly sighting and investigating unknown vessels (28 May–18 June).

Marblehead discovered Spanish armored cruiser Cristóbal Colón anchored near the mouth of the channel into Santiago, followed by sightings of several of the other enemy ships anchored within, on 29 May 1898. Iowa sighted the Spanish cruiser at 0740. At 1000 Schley cabled the discovery of the enemy, and the U.S. ships vigilantly observed the Spanish ships during the succeeding days. Iowa coaled from Merrimac on 30 May, and the Americans then engaged the Spaniards.

Commodore Schley transferred his pennant to Massachusetts at 1030 on 31 May 1898, and Iowa cleared for action at 1315. Massachusetts led cruiser New Orleans (ex-Amazonas) and Iowa in column at double distance, about east by north at ten knots. Schley signaled the ships to “Fire steadily with greatest practicable precision.” The Americans sighted Cristóbal Colón at 1350 and Massachusetts opened fire, followed by New Orleans a minute later and Iowa at 1356. The ships set their gun sight’s range at 8,500 yards but the shots fell short, and they raised their settings to 9,000 yards. Massachusetts ceased fire and turned with a port helm and headed about west. Iowa ceased fire and followed the flagship at 1401.

Massachusetts reopened fire at 1405, again followed by New Orleans a minute later and Iowa at 1408. The ships decreased their speed and set their sights at 9,500 yards, but gradually increased their sights to a range of 11,000 yards. Nearly all of the shots fell slightly short, but Evans observed that they appeared to “burst or graze” the Spanish vessels, and surmised that at least some of the fragments damaged the enemy. The ships ceased fire and came about, Iowa at 1416. Cristóbal Colón and some of the forts returned fire throughout the run but their rounds all missed—though several shells splashed close aboard Iowa as she retired. Iowa secured her battery at 1450, and Schley transferred his flag to converted yacht Vixen and then to Brooklyn. The Spanish ceased fire at 1510.

Sampson broke his flag in New York in command of the ships gathered in the waters off Santiago on 1 June 1898. A stalemate ensued. The narrow channel into Santiago, flanked by Spanish shore batteries and possibly blocked by mines, prevented the Americans from entering the harbor, but the enemy could not elude the blockaders. An attempt on 3 June to obstruct the narrowest part of the channel, by sinking the collier Merrimac in the waterway, had failed when she had sunk “somewhat farther in than had been intended…”

The Army’s V Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. William R. Shafter, sailed from Tampa, Fla., for Cuba on 14 June 1898. Iowa put in to Guantánamo Bay (18 and 28 June). Sampson and Shafter conferred about their divergent strategies on 20 June. Sampson hoped that the Army intended to capture the shore batteries around Santiago to enable the Navy to overwhelm the defenders, but Shafter preferred that the Navy support the advance on the city. Shafter landed his troops at Daiquirí (22–25 June), and then pushed toward Santiago. Disease savaged the men, and they sustained alarming casualties during the fighting at El Caney and San Juan and Kettle Hills on 1 July.

Some of the U.S. ships shelled the Spanish forts at Aguadores on 1 July 1898, and Indiana and Oregon (Battleship No. 3) bombarded the Spanish batteries at the entrance of the harbor, concentrating on the Punta Gorda battery, on 2 July. Sampson dispatched a report of this bombardment to Shafter, observing that he could not force an entrance to the harbor until they could clear the channel of mines. The admiral added that enemy shore fire would interfere with minesweeping, and urged the general to seize the forts at the entrance to the harbor. Shafter and Sampson decided to meet at Siboney, east of Santiago, the following day, 3 July. Early that morning, the admiral sailed toward Siboney in New York, escorted by Ericsson (Torpedo boat No.2).

The American advance threatened to seize the heights overlooking the city, and artillery emplaced on those hills could sweep the harbor. Captain-General Ramón Blanco y Erenas therefore ordered Cervera to attempt to escape with the Flota de Ultramar (Caribbean Squadron), thus precipitating the Battle of Santiago de Cuba. Cervera ordered his ships to raise steam in their boilers overnight. The admiral entertained few illusions concerning the outcome, however, because his ships were largely in poor repair and under-armed in comparison to the U.S. ships. Fouled bottoms and poor quality coal reduced their speed. In addition, while some of the men from Cristóbal Colón served ashore with a naval brigade—they returned to their ship on 2 July—most of the crews lacked training. The small Spanish gunboat Alvarado surreptitiously lifted some of the mines that blocked the channel entrance to enable the ships to pass into the open sea.

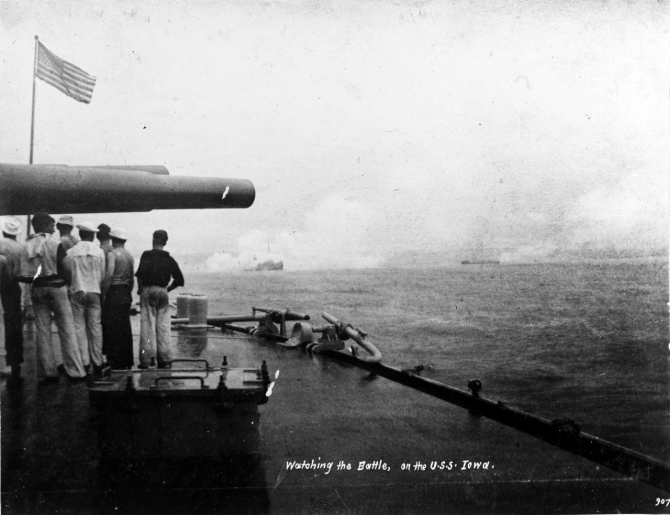

Cervera, his flag in armored cruiser Infanta Maria Theresa, gallantly led his squadron out at 0845 on 3 July 1898, followed by armored cruisers Vizcaya, Cristóbal Colón, and Almirante Oquendo, and torpedo boats Furor and Plutón. The Spaniards emerged from the harbor at 0935. They chose a propitious moment, because New York steamed about seven miles to the eastward and four miles from her usual blockading station in order to facilitate the meeting between Sampson and Shafter, while Massachusetts lay at Guantánamo Bay, coaling. The remaining U.S. ships blockaded the harbor in a rough semi-circle from east-to-west: Indiana, Oregon (Battleship No. 3), Iowa, Texas, and Brooklyn, with Schley wearing his flag in Brooklyn. Two armed yachts patrolled immediately outside the harbor mouth --Vixen to the westward and Gloucester to the eastward.

Iowa held her blockading position off the entrance to the harbor, bearing about south, three to four miles from El Morro, the steam in her boilers proving sufficient to enable her to steam at five knots. The bugle sounded quarters and the crew stood for Sunday inspection at 0915. “The men were not in a very amiable mood,” Seaman W.J. Murphy of the ships company recalled, “for quarters is not a very cherishing period on board a man of war and is cursed softly and stiffly below and aloft forward and aft.” As Lt. Cmdr. Raymond P. Rodgers, Iowa’s executive officer began to inspect the last line of crewmen, Brooklyn sighted a plume of smoke from one of the Spanish ships, fired a gun, and hoisted the signal: “The Enemy is coming out!”

The American ships sounded general quarters and got up steam to their boilers. The enemy vessels steamed at eight to ten knots until they cleared the channel, and then increased speed. “The [Spanish] squadron,” Evans later reported, “moved with precision and stations were well kept.” They swept past Vixen, and moved west along the Cuban coast in a desperate bid to escape. Cervera valiantly thrust Infanta Maria Theresa at Brooklyn to grant his squadron the time to build speed.

Ten minutes after the Spanish emerged from the harbor, Brooklyn, Iowa, and Texas opened fire—Iowa at 0940 from a range of 6,000 yards. Iowa laid a course that enabled her to speedily drop the range to 4,000 yards, then 2,500, 2,000, and 1,200. The Americans resolutely pursued the enemy, Secretary of the Navy John D. Long later reporting that they “at once engaged [them] with the utmost spirit and vigor.” Gloucester, Lt. Cmdr. Richard Wainwright in command, tenaciously chased the Spanish torpedo boats, narrowly avoiding Indiana’s and Iowa’s shells splashing around her.

Evans determined that Infanta Maria Theresa would pass ahead of Iowa and had the helm put to starboard, and the ship fired a broadside at the armored cruiser at a range of 2,500 yards. Iowa then put her helm to port and headed across the bow of Vizcaya, the second ship in the column. Vizcaya briefly drew ahead, and Iowa put the helm to starboard and fired a full broadside at a range of 1,800. Iowa was headed off with port helm for Cristóbal Colón, the third ship, and she put her helm to starboard and matched her course with the Spanish cruiser. Iowa opened fire with her entire battery, including the rapid-firing guns, from a range of 1,400 yards. The ship’s guns again enveloped her in dense smoke. “As soon as you see a head,” Murphy explained, “hit it for it was impossible to see what ship you were firing at.”

Cristóbal Colón and Almirante Oquendo returned fire. The Spanish forts also fired at the American ships at the beginning of the battle, though their fire slackened as the range opened when the U.S. ships pursued the enemy vessels. A Spanish shell, estimated to be a 6-inch round, struck Iowa’s hull two or three feet above the actual water line and almost directly on the line of the berth deck, piercing the ship’s side between frames 9 and 10. This shell made a large and ragged hole, about seven inches high and 16 wide, but did not penetrate beyond the inner bulkhead of the cofferdam A 41–43. It did not explode, and crewmen subsequently removed it from the cofferdam.

A second round plunged into Iowa and the cofferdam A 105, between frames 18 and 19, punching a hole the upper edge of which lay immediately below the top of the cofferdam on the berth deck in compartment A 104. The hole measured about five feet above the water line, and two to three about the berth deck. The projectile broke off the hatch plate and coaming of the water-tank compartment, exploded, and perforated the bulkheads of the chain locker. The explosion created a small fire, but crewmen promptly extinguished the blaze. One fragment struck a link of the sheet chain wound around the 6-pounder ammunition hoist, cutting the link in two. Another fragment punctured the cofferdam on the port side and slightly dished the outside plating. Two or three other small rounds hit about the upper bridge and smokestacks but inflicted only minimal damage. Four other small shells struck the hammock nettings and the side aft. None of these hits slowed Iowa and she staunchly clung to the Spanish ships.

Repeated U.S. salvoes crashed into Infanta Maria Theresa and Almirante Oquendo. Fires blazed on board Infanta Maria Theresa and threatened to touch off her magazines, so Cervera ran her aground about eight miles to the west of Santiago at 1025. Five minutes later, Almirante Oquendo also drove ashore to avoid a catastrophic explosion. Vizcaya came hard to starboard and ran aground during the forenoon watch. Iowa poured fire into Vizcaya and the Spanish ship struck her colors at 1036. Iowa ceased fire but her crewmen cheered as the cruiser lowered her flag.

The Spanish torpedo boats suffered terribly. A 13-inch shell from Indiana sliced through Plutón’s engine room, cutting down most of the men within and nearly tearing the destroyer in two. Evans afterward described how Indiana, Iowa, and Oregon also turned their rapid-fire guns on “the venturesome little craft,” initially from a range of 4,500 to 4,000 yards. Furor struck her flag to Gloucester and Plutón ran onto the rocks and exploded.

The battleship proved unable to catch Cristóbal Colón, and she therefore hoisted out two steam cutters and three cutters to rescue the Spaniards at about 1100. Iowa’s sailors pulled Capt. Don Antonio Eulate, Vizcaya’s commanding officer, from the water. Eulate surrendered his sword to Evans, who courteously returned it. In addition, Iowa received 23 Spanish officers and 248 petty officers and men—32 of them wounded. The ship buried five Spaniards with honors. Iowa’s crewmen also brought a number of survivors on board Ericsson and auxiliary dispatch vessel Hist. Cristóbal Colón ran aground at the mouth of the Tarquino River during the afternoon watch. Iowa fired a total of 31 12-inch semi-armor-piercing shells, and 35 8-inch, 251 4-inch, 1,056 6-pound, and 100 one-pound common rounds.

The Americans lost one man killed and ten wounded—mostly ear drum damage from the concussion of the guns. The Spaniards lost an estimated 350 men killed in action or drowned, 160 wounded, and 1,670 captured, including Cervera. The Americans detained the officers at Annapolis, Md., and the enlisted men at Camp Long, on Seavey’s Island, Portsmouth, N.H., but released them following the war. The U.S. siege tightened around Santiago, and the Spanish garrison surrendered on 16 July.

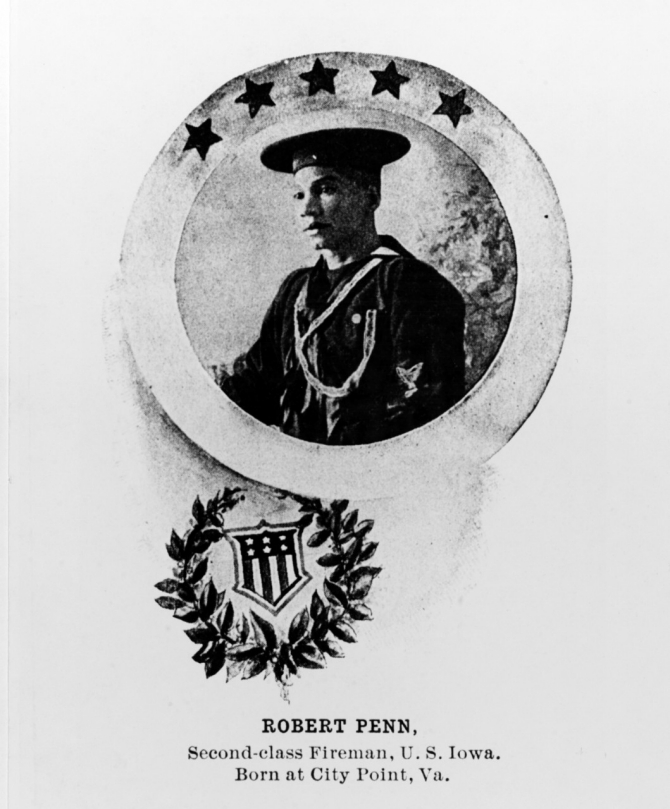

Four days later, an event took place on board Iowa that illustrated how heroic actions occurred outside of combat. The manhole gasket blew out in the battleship’s fireroom while she patrolled off Santiago de Cuba on 20 July 1898. Fireman 2nd Class Robert Penn risked serious scalding from the water that erupted from the boiler, and hauled the fire while standing on a board thrown across a coal bucket, only a foot above the boiling water. Penn subsequently received the Medal of Honor for his heroism.

Following the Spanish surrender, Iowa sailed from Cuban waters, arriving at New York on 20 August 1898. Capt. Silas W. Terry assumed command on 24 September. On 12 October, she departed for duty in the Pacific, and entered dry dock at Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Wash., on 11 June 1899. After her yard period, the ship carried out training while anchored off San Diego, Calif. (20 December 1899–15 January 1900). While there, Iowa also augmented her armament by the addition of two 3-inch field guns and four .30-caliber Colts, for use by her sailors and marines when they fought ashore.

During one of these exercises, Iowa lost a Howell Mark 1, No. 24 torpedo, on 20 December 1899. Lt. Cmdr. John A. Howell had developed the weapon between 1870 and 1889. The type averaged 11 feet long, was made of brass, reached a range of 400 yards and a speed of 25 knots, and carried a warhead filled with 100 pounds of explosive. The practice warhead, which was attached to the midsection by four pins and a single screw, probably detached. Well over a century later, in March 2012, two dolphins in the Navy’s Marine Mammal Program located the mid- and tail- sections of the torpedo and the Underwater Archeology Branch of the Naval History & Heritage Command subsequently desalinized and conserved the weapon for preservation.

After refit, Iowa served in the Pacific Squadron for two and a half years, conducting training cruises, drills, and target practice. Capt. Philip H. Cooper relieved Capt. Terry as commanding officer on 9 June 1900. Capt. Thomas Perry relieved Capt. Cooper on 1 April 1901. Iowa left the Pacific to serve as the flagship of the South Atlantic Squadron (early February 1902). She visited Montevideo, Uruguay (late July–2 August, 22–28 September, and 22 October–6 November); Brazilian ports comprising Santos (6–7 August), Bahia (11 August–8 September and 11–14 September), Trade Island (8–14 September), and Rio de Janeiro (10–18 November); and Puerto Militar (subsequently renamed Puerto Belgrano), Argentina (28 September–19 October).

The battleship put in to the Gulf of Paria, West Indies (29 November–4 December 1902), and from there carried out a search problem off Mayaguez, P.R. (9–10 December), and visited and then maneuvered off Culebra Island, P.R. (11–15 and 15–19 December, respectively). Iowa visited St. Lucia (21 December) and celebrated Christmas at Port of Spain, Trinidad (22–28 December), before returning to Culebra (30 December 1902–1 February 1903).

She visited St. Kitts (2–6 February 1903) and Ponce, P.R. (6–11 February), and then sailed for New York on 12 February. Iowa visited Galveston, Texas (18–26 February), and Pensacola, Fla. (28 February–1 April), conducted target practice off Pensacola (1–9 April), and completed repairs at Pensacola Navy Yard (9–23 April). The ship reached Cape Henry, Va. (28–30 April), Tompkinsville, N.Y. (1–7 May), and New York Navy Yard on 7 May. Capt. Henry B. Mansfield relieved Capt. Thomas Perry as the commanding officer on 11 May. Iowa was decommissioned at New York Navy Yard on 30 June.

Iowa was recommissioned on 23 December 1903. The Bureau of Construction and Repair reported replacing the ship’s two 4-inch guns on the after bridge with two 6-pounders on 8 January 1904. The ship subsequently joined the North Atlantic Squadron and made for European waters. She celebrated Independence Day at the Piraeus, Greece (30 June–6 July 1904), and visited Corfu (8–9 July); Trieste and Fiume, Austria-Hungary (12–24 and 25–30 July, respectively); and Palermo, Italy (2–4 August). She visited Gibraltar (9–13 August), and then returned to the United States, stopping at Horta, Fayal, Azores (18–20 August) en route. Iowa stayed at Menemsha Bight, Mass. (29 August–5 September) while she awaited her turn to use Target Range No. 3 off Martha’s Vineyard. The ship carried out target practice at the range (5–19 September), and visited Tompkinsville (30 September–5 October) and lay to off Sixty-fifth Street, North [Hudson] River, N.Y. (5–20 October) while she awaited orders to undergo repairs. Iowa put into Old Point Comfort, Va. (22–24 October), and then completed repairs and painting at Norfolk Navy Yard, Va. (24 October–24 December) and in dry dock at Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co. (24–30 December).

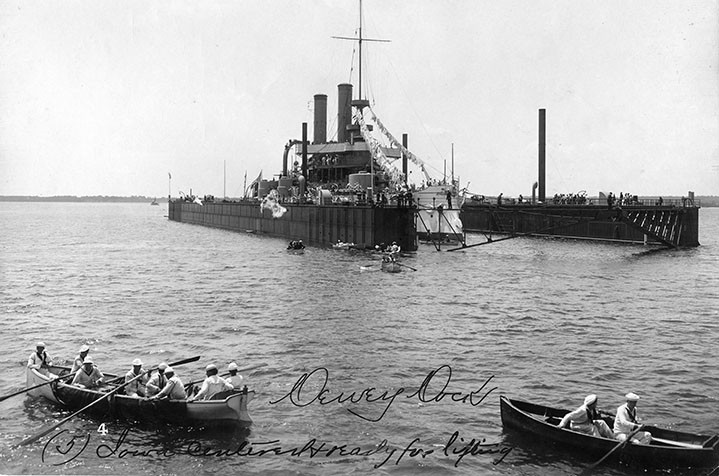

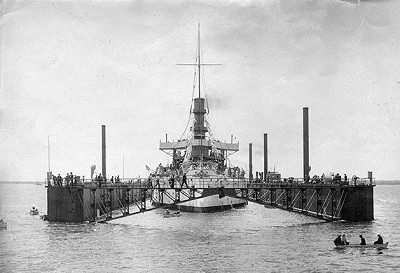

She rejoined the fleet at Hampton Roads, Va. (3–9 January 1905). Capt. Benjamin F. Tilley relieved Capt. Mansfield as the commanding officer on 14 January. Iowa cruised with other ships for a series of training exercises off Culebra (15–17 January), Guantánamo Bay (19 February–22 March), and Pensacola, Fla. (27 March–2 May). Iowa returned to Hampton Roads (7–9 May), carried out repairs at Norfolk Navy Yard (9 May–24 June), tested Dewey self-docking steel floating dry dock at Solomons Island, Md. (25–30 June), and completed upkeep at Newport News (30 June–3 July).

The ship sailed to New England waters and visited Provincetown, Mass. (5–12 July 1905) and Newport (13–19 July) before she came about and visited Annapolis (23–24 July). Iowa put in to Hampton Roads (25–26 July), and then made another northerly cruise and visited New York (27 July–1 August and 1–12 October); Bar Harbor, Maine (3–10 August); Boston (11–15 August); Provincetown (15–17 August and 29–30 September); Newport (19–25 August); and Watch Hill, R.I. (25–28 August); and carried out gunnery practice on the target range in Cape Cod Bay (12–29 September). She returned to Hampton Roads (13–30 October), then visited Annapolis (30 October–7 November).

Iowa made another northward voyage and visited North River, N.Y. (8–20 November 1905), and came about for Hampton Roads (21–22 November), and for work at Norfolk Navy Yard (22 November–23 December) and repairs while in dry dock at New York Navy Yard (26–28 December). The battleship returned to Hampton Roads (31 December 1905–17 January 1906).

She then made for Caribbean waters and visited Culebra (22 January–6 February 1906); Barbados (8–15 February); and Guantánamo Bay (19 February–31 March); and carried out gunnery practice at the range off Cape Cruz, Cuba (1–10 April). Iowa steamed with the Atlantic Fleet’s Second Division off Guantánamo Bay (11–13 April). The ship returned to Annapolis and participated in the ceremony commemorating the exhumation of John Paul Jones from his original grave in Paris, France, for interment at the U.S. Naval Academy (17–27 April).

The ship visited Hampton Roads (27–29 April and 1–4 May 1906), Newport News (29 April–1 May), and New York (5–13 May). The Bureau of Construction and Repair reported the removal of her two Howell 14-inch torpedo tubes on 7 May. She then completed an overhaul at Norfolk Navy Yard (14 May–30 June).

Iowa celebrated Independence Day at Tompkinsville (1–6 July 1906), and coaled and underwent repairs while in dry dock at New York Navy Yard (6–15 July). She then sailed with ships of the Second Division on a voyage through New England waters. Iowa coaled at Newport (31 July–8 August) and East Lamoine, Maine (26–29 August). In addition, she visited Provincetown (16–18 July); Rockport, Mass. (with the First Squadron – 18–30 July); Newport (31 July–8 August); Rockport (9–17 August); Boston (17–18 August); and Portland, Maine (in company with Indiana -- 18–26 August). Iowa visited Camden, Maine (she temporarily rejoined the First Squadron -- 29–30 August), and took part in ceremonies in connection with the unveiling of a monument to Quartermaster William Conway that honored his “sturdy loyalty” in refusing to haul down the Stars and Stripes when Confederate forces seized the Pensacola Navy Yard on 12 January 1861.

Iowa made for Smithtown Bay, Long Island Sound, N.Y., where she prepared for a Naval Review (1–2 September 1906). President Theodore Roosevelt reviewed a number of ships including Florida (Monitor No. 9), Indiana, Truxtun (Destroyer No. 14), and transport Yankee at Oyster Bay, N.Y. (2–4 September). Iowa then coaled at Bar Harbor (6–23 September), visited Provincetown (24–27 September), and carried out gunnery shoots at the target range in Cape Cod Bay (27 September–14 October). The ship returned to Hampton Roads (16–17 October), and underwent repairs at the Norfolk Navy Yard (17 October–17 December).

Capt. Henry McCrea relieved Capt. Tilley as commanding officer on 12 December 1906. Iowa tested a coaling-at-sea apparatus at Hampton Roads and Lynnhaven Bay, Va. (17 and 18–19 December, respectively). She returned to Hampton Roads (19–20 December), underwent repairs in dry dock at New York Navy Yard (21–27 December), and rejoined other ships of the Atlantic Fleet at Tompkinsville (27–28 December) and off Cape Charles, Va. (29–31 December), before returning to Hampton Roads (31 December 1906–2 January 1907).

Iowa made for Caribbean waters and conducted maneuvers and exercises off Guantánamo Bay (7 January–10 February 1907). She visited Cienfuegos, Cuba (11–16 February), and Guantánamo (17 February–15 March). The battleship accomplished gunnery training at the nearby target range (16 March–6 April), and rejoined the fleet at Guantánamo (7–10 April).

She participated in a portion of the Jamestown Exposition, commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown Colony, held at Sewell’s Point, Hampton Roads (15 April–15 May 1907). Iowa then sailed with other ships of the Atlantic Fleet and visited North River (16 May–5 June). She rendezvoused with the Fourth Division and maneuvered and obtained tactical data while off Cape Charles (6–7 June), on the Southern Drill Grounds (19–21 and 26–28 June), and at Hampton Roads (7–19 and 21–26 June). At the end of that period of work in the Tidewater area, the ship returned to Hampton Roads on 28 June.

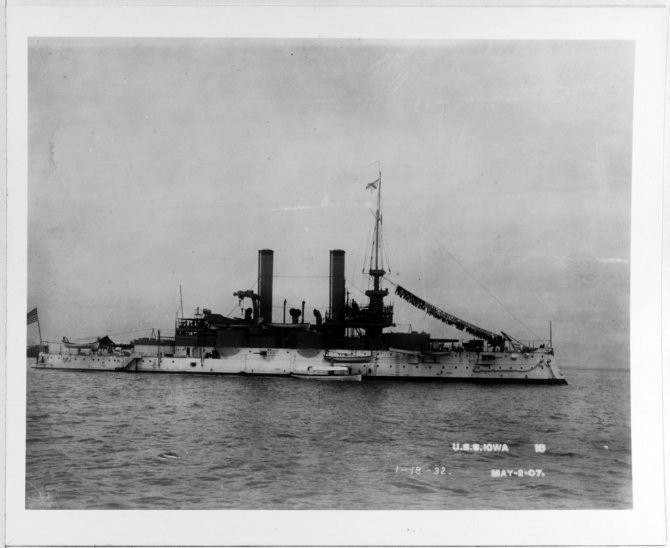

Iowa served along the East Coast until she was placed in reserve at Norfolk Navy Yard on 6 July 1907. On that date, Lt. Cmdr. Clarence S. Williams also relieved Capt. McCrea as the commanding officer. Lt. Cmdr. Albert L. Norton relieved Lt. Cmdr. Williams on 25 October 1907. Iowa was decommissioned at Philadelphia on 23 July 1908. By that point, the Bureau of Construction and Repair noted that her armament comprised four 12-inch, eight 8-inch, ten 4-inch (the additional 4-inch guns to enable her to better deal with the threat of torpedo boats), four 6-pounders, two 1-pounders, two 3-inch field guns, and four Colts. During her time in reserve, she also received a cage mainmast and modifications to her 4-inch magazines and shell hoists, and electric machinery replaced the hydraulic equipment in her main battery turrets.

Recommissioned at the New York Navy Yard on 2 May 1910, Cmdr. William H.G. Bullard in command, Iowa completed fitting out, and on 23 May sailed for Annapolis, where she joined the Naval Academy Practice Squadron (24 May–6 June). They carried out a brief training cruise to Hampton Roads (7–9 June). The squadron embarked midshipmen, sailed to European waters, and visited Plymouth, England (23–30 June); Marseille, France (8–15 July); Gibraltar (19–24 July); Funchal, Madeira (27 July–2 August); and Horta, Azores (5–12 August). The ships returned to the United States at Solomons Island, Md. (22–28 August) and then disembarked the midshipmen at the Naval Academy (28 August–3 September). Capt. George B. Clark relieved Cmdr. Bullard as the commanding officer on 30 August.

After workmen at the New York Navy Yard installed a coaling-at-sea apparatus on board Iowa (6–19 September 1910), Iowa carried out coaling tests in company with collier Vestal at Lynnhaven Roads on 22 September. Four days later, the ship was placed in first reserve at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 26 September. Lt. William O. Spears relieved Capt. Clark on 19 April 1911. Cmdr. Benjamin F. Hutchinson relieved Lt. Spears on 1 May.

Iowa was recommissioned at Philadelphia on 3 May 1911, and soon again cruised with the Naval Academy Practice Squadron (13 May–5 June), making another midshipman summer voyage to European waters, visiting Queenstown, Ireland (18–27 June); Kiel, Germany (2–12 July); Bergen, Norway (14–24 July); and Gibraltar (2–8 August). The squadron returned to Solomons Island (22–28 August) and disembarked the midshipmen at Annapolis (28–29 August). The ship was placed in reserve at Philadelphia on 1 September. Lt. Cmdr. George C. Sweet relieved Cmdr. Hutchinson as the commanding officer on 30 September. Iowa took part in a brief mobilization of the Atlantic Fleet at New York and returned to Philadelphia (28 October–2 November).

Cmdr. William W. Phelps relieved Lt. Cmdr. Sweet on 23 May 1912. Iowa sailed on a Naval Militia cruise and visited Newport (2–5 July); Tangier Sound, Chesapeake Bay (7–9 and 15–17 July); Baltimore, Md. (10 July); New York (12–13 and 21 July); and Annapolis (18–19 July). The ship served with the Atlantic Reserve Fleet at Philadelphia (22 July–8 October). Iowa then participated in a Naval Review at Philadelphia (10–15 October 1912). Cmdr. Gilbert P. Chase relieved Cmdr. Phelps as the commanding officer on 30 October 1912. Cmdr. Phelps returned to the ship when he relieved Cmdr. Chase as the commanding officer on 18 January 1913. The battleship was placed in ordinary at Philadelphia on 30 April. Lt. Cmdr. William P. Scott relieved Cmdr. Phelps as the commanding officer on 13 May 1913.

She was decommissioned at Philadelphia Navy Yard on 23 May 1914. At the outbreak of World War I, Iowa was placed in limited commission as a receiving ship on 23 April 1917. After serving as Receiving Ship at Philadelphia for six months, she was sent to Hampton Roads, Va., and remained there for the duration of hostilities, training men for other ships of the Fleet, and doing guard duty at the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. She was decommissioned for the final time on 31 March 1919. Her complement upon decommissioning consisted of 420 sailors (including 107 in her engineering force), 26 officers, and 60 marines. Iowa was redesignated and renamed Coast Battleship No. 4, in order to make her name available for Iowa (Battleship No. 53), on 30 April 1919.

The Navy assigned the ship for use in gunnery exercises, engineering performances, and certain radio-control experiments, on 4 January 1920. During her final years she also served as a radio controlled target ship. Coast Battleship No. 4 was stricken from the Navy List on 4 February 1920, but on 10 February the Navy revoked the strike order. Coast Battleship No. 4 was turned over to the commanding officer of Ohio (BB-12) on 2 August 1920.

The services began a series of bombing tests off the Virginia capes on 21 June 1921. The Navy planned the evaluations to provide detailed technical and tactical data on the effectiveness of aerial bombing against ships, and of the value of compartmentation to enable vessels to survive such damage. The Army participated, subject to the Navy’s proviso of the bombing accomplished as a series of controlled tests, and that inspectors boarded the target vessels following each attack to assess the effects of the sizes and types of ordnance used.

Navy planes located the radio-controlled Coast Battleship No. 4 in one hour, fifty-seven minutes, after being alerted to her approach somewhere within a 25,000 square mile area, and attacked Coast Battleship No. 4 with dummy bombs, on 29 June 1921. The Navy opposed an Army plan to launch additional attacks, because Coast Battleship No. 4 provided an unfair advantage by maneuvering under radio control. The rudimentary aerial navigation equipment available hindered testing, however, and many of the participants could not have found the ships unaided.

The annual fleet problems concentrated the Navy’s power to conduct maneuvers on the largest scale and under the most realistic conditions attainable. The primary phase of Fleet Problem I (18–22 February 1923) included a test of the defenses of the Panama Canal against aerial attacks. Additional exercises followed.

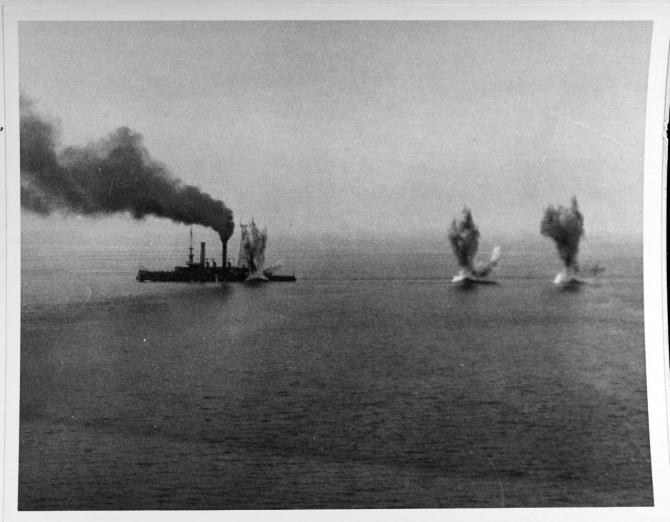

Battleship Mississippi (BB-41) fired her 5-inch guns during a number of practice runs at Coast Battleship No. 4, in Panama Bay, Canal Zone, as the latter steamed at a range of 11,000 yards, closed the range to about 8,000 yards, and then sank Coast Battleship No. 4 with a salvo of 14-inch shells that struck her amidships. A number of vessels including aircraft carrier Langley (CV-1) – that arrived with a congressional delegation embarked to view her air operations after the Fleet Problem concluded -- operated in the area and observed her final moments, and battleship Maryland (BB-46) piped all hands to the rail and fired a 21-gun salute as Coast Battleship No. 4 slid beneath the waves. The veteran of Santiago was stricken on 27 March 1923, and sold for salvage and scrap on 8 November.

Iowa (Battleship No. 53) was laid down on 17 May 1920 at Newport News, Va., by Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co., but, on 8 February 1922, work was suspended when the ship (redesignated BB-53 on 17 July 1920) was 31.8% complete. Construction was cancelled altogether on 17 August 1923 in accordance with the terms of the Washington Treaty Limiting Naval Armaments. Her materials were sold for scrap on 8 November 1923.

Mark L. Evans

1 October 2015