YP-72

1940-1943

(YP-72: displacement 115; length 93'; beam 23'9"; draft 14'; speed 11 knots; complement 18; armament 1 3-inch – gradually increased to ultimately include 2 .50 caliber machine guns, 2 20 millimeter machine guns, 2 .30 caliber Lewis machine guns; 2 depth charge tracks)

The wooden-hull diesel-engine purse seiner Cavalcade -- completed in 1940 at Tacoma, Wash., by the J. M. Martinac Shipbuilding Corp. -- was acquired by the Navy from W. D. Suryan, of Anacortes, Wash., on 6 November 1940; received by the Navy that same day at Seattle, Wash.; and immediately taken in hand for conversion at the Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Wash. Classified as a district patrol vessel (YP) and earmarked as a “group leader,” the former fishing craft was commissioned at her conversion yard as YP-72 on 28 November 1940, 53-year old Swedish-born [naturalized] Lt. Cmdr. Carl E. “Squeaky” Anderson, D-V(S), USNR, a colorful master mariner widely “recognized for his knowledge of the Alaska coast and his wizardry with docks,” in command.

YP-72, with Lt. Cmdr. Anderson as Commander, Aleutian Patrol, departed Bremerton on 12 December 1940, and reached Dutch Harbor, Territory of Alaska, on the day before Christmas [24 December]. Soon thereafter, on the last day of the year, YP-72 towed YP-73 to the Pacific American Fisheries’ yard for repairs to the latter’s tail shaft.

Based at the Naval Air Station (NAS), Dutch Harbor, YP-72 occasionally served as a transport, such as providing passage for U.S. Army Staff Sgt. B. M. Bates and Cpl. C. J. Janus from Dutch Harbor to Kodiak (26-30 March 1941) and carried out extensive cruising in all kinds of weather. During one severe storm, a typewriter (a rust-proof Underwood Model 11) broke loose from its fastenings and received irreparable damage when thrown to the deck on 10 April. The harsh weather also exacted a toll on the ship’s allotment of colors, fraying and tearing ensigns, jacks, and commissioning pennants. Towing work caused wear-and-tear on Manila rope, and while mooring a target to be used by the U.S. Army’s Coast Artillery guns at Fort Mears, Dutch Harbor, YP-72 lost an anchor on 17 August.

In the wake of the Japanese onslaught in the Pacific in December 1941, YP-72, Ens. Harvey D. Stackpole, D-V(S), USNR, Alaskan-born and an Oregon native, in command by the end of the year, received a pair of .50 caliber machine guns, the Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) considering that to be “a reasonable battery for this size craft.” Given weight and stability considerations, BuOrd recommended that “ready-service ammunition be held to a minimum and that the cooling system and splinter protection be omitted…”

Less than six months after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese brought the war to the Alaskan territory on 3 June 1942, when the Second Strike Force (Rear Adm. Kakuta Kikuji), centered around the aircraft carriers Ryūjō and Junyō, bombed Dutch Harbor. The same force reprised the attack on 5 June, and occupied the island of Attu the same day without opposition. Two days later, on 7 June, a Japanese force carried out an unopposed occupation of the island of Kiska.

On 10 July 1942, as Lt. William N. Thies, A-V(N), USNR, of Patrol Squadron (VP) 41, flew his PBY Catalina past the southwest side of Akutan Island while returning from a routine tactical patrol, one of his crew “sighted a small crashed Japanese plane on its back. From its size…a zero type Navy fighter.” What had been seen by the crewman on board Thies’s Catalina was indeed a Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 0 Model 21 kanjō sentōki (abbreviated kansen) [carrier fighter], that had been flown during the strike on Dutch Harbor on 3 June by Petty Officer Koga Tadayoshi of the Ryūjō’s hikōkitai [air unit]. His kansen damaged by antiaircraft fire, Koga had spotted level ground on Akutan Island. Unaware of the nature of the treacherous terrain ahead of him, however, he “apparently attempted to make a normal wheels-down, flaps-down stall landing in the soft ground, skidded along for a short distance carrying away the landing struts, damaging flaps, and belly tank and going over on its back, in which position he skidded somewhat further damaging the wing tips, vertical stabilizer and trailing edge of the rudder.”

Lt. Thies hastened back to Dutch Harbor and made his report, after which Lt. Cmdr. Paul Foley, Jr., VP-41’s commanding officer, put him in charge of a party “to investigate and salvage such parts of the plane as were of intelligence value.” The district patrol vessel YP-151 transported Thies and his men to the island, where “after considerable struggle” in the terrain, they found the object of their search “in a high valley about a mile and a half from the beach in a soft marshy land.” The kansen rested “with the fuselage and engine half-buried in the knee-deep mud and water,” Petty Officer Koga’s head and shoulders submerged. He had suffered a broken neck in the crash. The first order of business for the salvage party lay in removing the pilot’s decayed body that was held firmly in place by two safety belts. Once the salvagers finally extracted Koga’s remains, they “buried [them] with simple military honors and Christian ceremony near the scene of the accident.”

The salvagers removed the two 20-millimeter wing guns, the optical reflector sight, and “certain small articles…for immediate attention,” finding, in so doing, “that the condition of the plane warranted attempts to recondition and flight test it.” They had also discovered, however, that the plane’s construction – wings integral with the fuselage – complicated the recovery process. With the “press of other operations” militating against further work that day, the salvage party returned in YP-151 to Dutch Harbor.

A second salvage attempt (12-14 July 1942), under Lt. Robert C. Kirmse, A-V(N), USNR, having encountered considerable difficulties and proved unsuccessful, YP-72 set out from Dutch Harbor on 15 July, towing a barge loaded with a medium-sized bulldozer fitted with a winch, a heavier pre-fabricated sled (the one employed on 12 July having proved inadequate) and “considerable gear and lumber.” Jerry Lund, an “experienced rigger…attached to the Siems Drake Construction Company,” having proven himself “invaluable” during the second salvage operation, had been placed in charge of the work.

While YP-72 (assigned to the Northwestern Sea Frontier the day after she had left Dutch Harbor, on 16 July), lay off Akutan Island, the little expedition’s ’dozer chugged through the surf and bulldozed “a sort of road” up a small river bed the mile and a half distance to the crash site. The salvagers dragged all of their gear up to where the plane lay and assembled the large sled. They first hoisted the 950-horsepower Sakae-12 14-cylinder twin-row radial engine off of the plane -- the tripods used for the work sinking three to four feet into the mud in the process -- and secured it onto a small sled. Next, the men hoisted the engine-less plane, still upside-down, onto the large sled. Fording two three-foot streams en route, the salvage party dragged the plane and its detached power plant down to the beach, through the surf, and onto the barge. Quite remarkably, in view of the rough terrain, that “difficult feat” had resulted in no further damage to the plane.

YP-72, the barge, and its priceless cargo, arrived back at Dutch Harbor on 18 July 1942. There, workers righted the aircraft and guards were posted to oversee the cleaning process, although as Cmdr. Foley later wrote, the cleaning had to be kept to a minimum since it had been impossible “to anticipate every whim of souvenir hunters.”

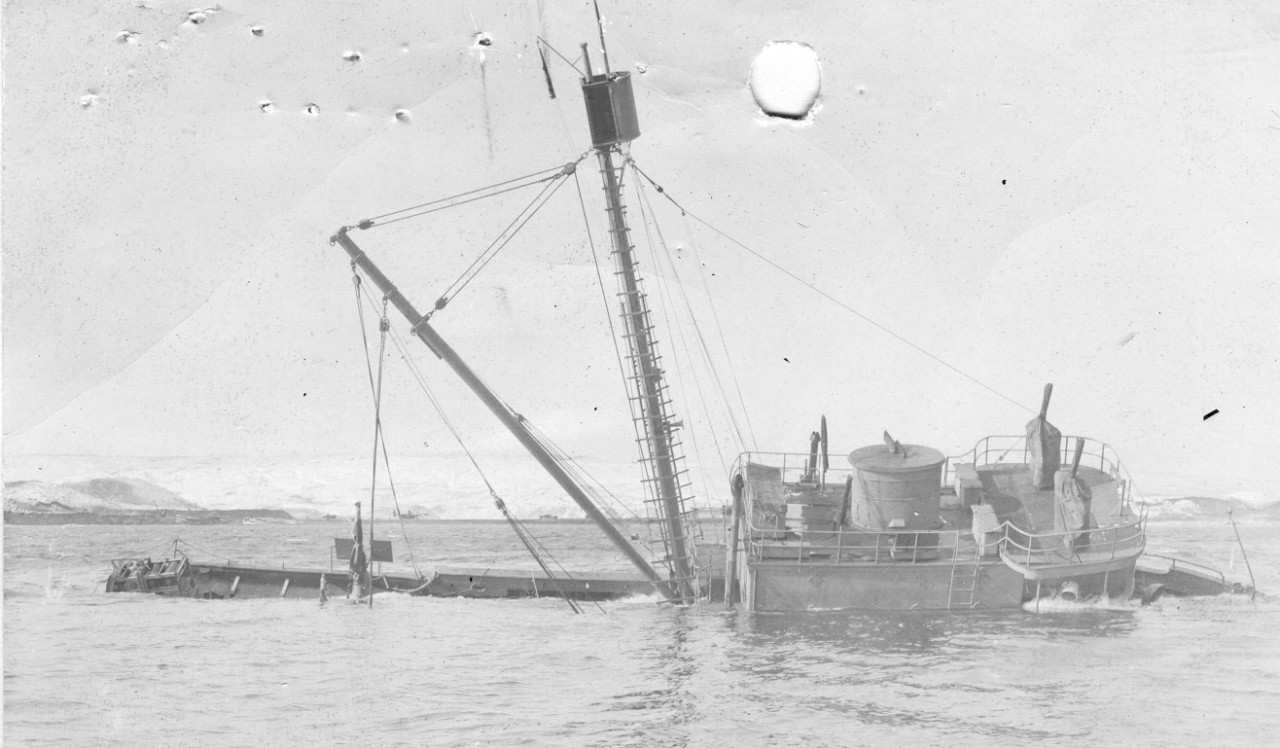

![Two .50-caliber machine guns having been added atop her pilot house, YP-72 rests from her labors (L), while operations unfold to right the Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 0 Model 21 kanjō sentōki (abbreviated kansen) [carrier fighter], tail code DI-108, on ... Two .50-caliber machine guns having been added atop her pilot house, YP-72 rests from her labors (L), while operations unfold to right the Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 0 Model 21 kanjō sentōki (abbreviated kansen) [carrier fighter], tail code DI-108, on ...](/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/y/yp-72/_jcr_content/body/media_asset_1635450338/image.img.jpg/1489514876080.jpg)

YP-72 resumed her duties out of Dutch Harbor, and after almost two years of “hard duty,” she returned to the Puget Sound Navy Yard for an overhaul, arriving at her destination on 19 October 1942. Over the ensuing weeks, the ship underwent repairs and alterations that included a dry-docking, recaulking of the hull and deck, renewal of the galley range, an extension of her upper deck house, work on her heating and refrigeration systems, installation of a permanent degaussing system and recognition lights, JK9 and QBE-1 sound equipment, depth charge tracks, and two 20 millimeter Oerlikon machine guns. Thus prepared to return to Alaskan waters, she departed the yard on 5 January 1943.

Ultimately, YP-72, 29-year old Lt. Robert O. Sylvester, D-V(G) USNR, a Seattle native, in command, reached Adak on 16 February 1943. The next day, during a full northeasterly gale, the ship received orders from the Port Captain to get underway to locate and retrieve barges that had come adrift in the storm. YP-72 weighed anchor immediately and stood out amidst the swirling snow squalls, Sylvester posting himself and one of his experienced sailors on the bridge wings and an officer and a seaman on the flying bridge.

A quick search of Sweeper’s Cove in the severely restricted visibility conditions having proved fruitless, YP-72 stood into Kuluk Bay, came left, skirting Gannet Rocks, then steered various courses to keep a mile from land, circling around the western and northern shores toward Zeto Point. Lt. Sylvester ordered two-thirds ahead, giving his ship, whose boxy superstructure lay all forward, a five-knot speed, just enough to swing her bow into the wind. In the white fury of the tempest, however, neither Sylvester nor his lookouts could discern any identifiable landmarks. Reasoning that the set from the wind would take any barges adrift into Kuluk Bay, YP-72 came right and crossed that body of water, passing Finger Shoal about 500 yards distant, off the ship’s starboard side.

A circuit of Finger Bay having yielded the sight of no barges, Sylvester opted to make another search of the western shores of Kuluk Bay, in hopes of finding improved visibility conditions. Passing the outermost of Gannet Rocks about 400 yards to port, YP-72 set course north, to reconnoiter the western shore of Kuluk Bay. If the patrol vessel spotted a barge inshore, Sylvester believed that he could safely float a line down to it in one of the ship’s dories, experience – during a snowstorm, at night, and with a heavy sea running – having proved it could be done safely.

At 0930, however, YP-72 struck a submerged reef -- not shown thus on her chart -- amidships. Sylvester ordered the engines stopped, a distress call sent out by radio, the four dories launched, and the bilge pumps started. With all hands having donned life jackets, the commanding officer ordered the executive officer to gather the mens’ service and health records, pay accounts and the ship’s log and deposit them in a sack for the exec to take off the ship in the event of her having to be abandoned. “It was hard to tell,” Sylvester recounted later, “just how long she would hang on the reef as heavy seas were breaking over her and she was pounding and rolling quite severely.”

YP-72’s crew experienced “considerable difficulty” launching the four dories that had been nested on the ship’s windward side. The ship’s cook busily bailed out one until the sea painter parted and the boat began drifting inexorably toward the breakers. The boatswain’s mate, going to the aid of the cook, tried to bring a dory around to the lee side but soon found his boat in the grip of the strong current, too, heading toward the inhospitable shore. Neither man could return to the ship in the teeth of the fierce winds and seas. The surf tossed both dories ashore, demolishing one, but both sailors survived the experience and were given shelter in an Army dugout ashore.

While large quantities of splintered wood drifted up from the smashed hull, the pumps appeared to be holding their own. Having been informed that a tug was proceeding to her assistance, YP-72’s crew meanwhile broke out their largest line (6-inch) (having previously given 1,200 feet of 8-inch Manila hawser to YP-400) and made one fast to the towing bitt, then bent on a smaller line to the other end, and coiled it in one of the two surviving dories to be floated down to the tug upon her arrival.

Once help arrived in the form of the tug Port of Bandon, YP-72 signaled for her to lie down wind, at which time Lt. Sylvester ordered his two best seamen into one of the dories. They paid out the small line until they reached the tug. YP-72, however, had begun making water “very fast” and the action of the sea had ground away much of the keel and hull that the former purse seiner hung firmly on the reef. Abandoning any further attempt to save the ship, Sylvester put four men in the last dory and floated it down to the tug. Making the sea painter fast in the middle of the line, the boat then shuttled the remaining men to safety, all hands from the vessel mustering on board the tug at 1120. Counting the two men who had already reached shore, YP-72 had suffered neither loss of life nor injuries, and all 18 souls reached safety. Naval Air Facility, Adak, provided dry clothing and a place to sleep, thus allowing the crew to remain together in the wake of the disaster that had befallen their ship.

The next morning [18 February 1943], all “officers available [and] familiar with salvage work,” including Lt. Cmdr. Andreas S. Einmo, D-V(S), USNR, a naturalized Norwegian and a Seattle native, visited and inspected the ship with an eye toward freeing her from her predicament. Sadly, all concluded that “salvage of the vessel seemed impossible.” Consequently, the ship’s crew, utilizing a motor launch, brought off “all gear possible,” stripping the ship of all useful items.

“While abandoning ship and during salvage operations, the behavior of the officers and crew was most commendable,” wrote Lt. (j.g.) Sylvester later, “there being no hysteria, breakdown of morale of discipline, or laxity of duty. All hands were eager to salvage the ship and now wish to be put back together on another ship.” He also commended the tugmaster of Port of Bandon for his “fine work during rescue operations.”

The former purse seiner that had participated in the salvage of a priceless intelligence asset in the wake of the Aleutian phase of the Battle of Midway was stricken from the Navy List on 30 March 1943.

Robert J. Cressman

December 2014