Wasp VIII (CV-7)

1940–1942

Any of numerous winged hymenopterus insects possessing smooth, slender bodies, and an abdomen attached by a narrow stalk. They have well developed wings, biting mouthparts, and often administer painful stings.

VIII

(CV-7: displacement 14,700; length 741'4"; beam 80'8"; extreme width 109'0"; draft 19'11" (mean); speed 29.5 knots; complement 2,367; armament 8 5-inch, 16 1.1-inch, 16 .50-caliber machine guns; aircraft 80; class Wasp)

The eighth Wasp (CV-7) was laid down on 1 April 1936 at Quincy, Mass., by the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Co.; launched on 4 April 1939; sponsored by Mrs. Charles Edison, the wife of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Charles Edison; and commissioned on 25 April 1940 at the Army Quartermaster Base, South Boston, Mass., Capt. John W. Reeves, Jr., in command.

Wasp remained at Boston through May, fitting out, before she got underway on 5 June 1940 for calibration tests on her radio direction finder gear. After further fitting out while anchored in Boston harbor, the new aircraft carrier steamed independently to Hampton Roads, Va., anchoring there on 24 June. Four days later, she sailed for the Caribbean in company with Morris (DD-417).

En route, she conducted the first of many carrier qualifications. Among the earliest of the qualifiers was Lt. (j.g.) David T. McCampbell, who later became the Navy's top-scoring "ace" in World War II. Wasp arrived at Guantanamo Bay in time to "dress ship" in honor of Independence Day.

Tragedy marred the carrier's shakedown. On 9 July 1940, one of her Vought SB2U-2 Vindicators crashed two miles from the ship. Wasp bent on flank speed to close, as did the planeguarding destroyer Morris. The latter's boats recovered items from the plane's baggage compartment, but the plane itself had gone down with its crew of two.

Wasp departed Guantanamo Bay on 11 July 1940 and arrived at Hampton Roads four days later. There, she embarked planes from the First Marine Aircraft Group and took them to sea for qualification trials. Operating off the southern drill grounds, the ship and her planes honed their skills for a week before the Marines and their planes were disembarked at Norfolk; and the carrier moved north to Boston for post-shakedown repairs.

While civilian workmen from the Bethlehem Steel Co. came on board the ship to check their workmanship and to learn how it had stood up under the rigors of shakedown, Wasp lay alongside the same pier at which she had been commissioned. While at Boston, she fired a 21-gun salute and rendered honors to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose yacht, Potomac (AG-25), stopped briefly at the Boston Navy Yard on 10 August 1940.

Wasp departed the Army Quartermaster Base on the 21st to conduct steering drills and full-power trials. Late the following morning, she got underway for Norfolk. For the next few days, while Ellis (DD-154) operated as plane guard, Wasp launched and recovered her aircraft: fighters from Fighting Squadron (VF) 7, and scout-bombers from Scouting Squadron (VS) 72. The carrier put into the Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Va., on 28 August for repair work on her turbines -- alterations which kept the ship in dockyard hands into the following month. Drydocked during the period from 12 to 18 September, Wasp ran her final sea trials in Hampton Roads on 26 September 1940.

Ready now to join the fleet and assigned to Carrier Division (CarDiv) 3, Patrol Force, Wasp shifted to Naval Operating Base (NOB), Norfolk, from the Norfolk Navy Yard on 11 October 1940. There, she loaded 24 P-40's from the 8th Army Pursuit Group and eight O-47A's from the 2nd Observation Squadron, as well as her own spares and utility unit Grumman J2Fs on the 12th. Proceeding to sea for maneuvering room, Wasp flew off the U.S. Army Air Corps planes in a test designed to compare the take-off runs of standard Navy and Army aircraft. That experiment marked the first time that U.S. Army planes had flown from a U.S. Navy carrier.

Wasp then proceeded on toward Cuba in company with Plunkett (DD-431) and Niblack (DD-424). The carrier's planes flew routine training flights, including dive-bombing and machine gun practices, over the ensuing four days. Upon arrival at Guantanamo, Wasp's saluting batteries barked out a 13-gun salute to Rear Adm. Hayne Ellis, Commander Atlantic Squadron, embarked in the battleship Texas (BB-35), on 19 October.

For the remainder of October and into November 1940, Wasp trained in the Guantanamo Bay area. Her planes flew carrier qualification and refresher training flights while her gunners sharpened up their skills in short-range battle practices at targets towed by the new fleet tug Seminole (AT-65). While operating in the Culebra, Virgin Islands, area, Wasp again teamed with the aviators of the First Marine Aircraft Wing, giving the flying leathernecks practice in carrier take-offs and landings.

Her work in the Caribbean finished, Wasp sailed for Norfolk and arrived shortly after noon on 26 November 1940. She remained at the Norfolk Navy Yard through Christmas. Then, after first conducting degaussing experiments with Hannibal (AG-1), she steamed independently to Cuba.

Arriving at Guantanamo Bay on 27 January 1941, Wasp conducted a regular routine of flight operations into February. With Walke (DD-416) as her plane guard, Wasp operated out of Guantanamo and Culebra, conducting her maneuvers with an impressive array of warships: Texas, carrier Ranger (CV-4), heavy cruisers Tuscaloosa (CA-37) and Wichita (CA-45) and a host of destroyers. Wasp ran gunnery drills and exercises, as well as routine flight training evolutions, into March. Underway for Hampton Roads on 4 March, the aircraft carrier conducted a night battle practice into the early morning hours of the 5th.

During the passage to Norfolk, heavy weather sprang up on the evening of 7 March 1941. Wasp was steaming at standard speed, 17 knots, a pace that she had been maintaining all day. Off Cape Hatteras, a lookout spotted a red flare arcing into the stormy black night skies at 2245. The big ship swung around to head in the direction of the distress signal while a messenger notified the captain, who reached the bridge in an instant. Capt. Reeves himself took the conn, as a second set of flares was seen at 2259. Finally, at 2329, with the aid of her searchlights probing the wet night, Wasp located the stranger in trouble. She proved to be the lumber schooner George E. Klinck, bound from Jacksonville, Fla., to Southwest Harbor, Maine.

The sea, in the meantime, worsened from a state 5 to a state 7. Wasp lay to, maneuvering alongside at seven minutes into the mid watch on 8 March 1941. At that time, four men from the schooner clambered up a swaying Jacob's ladder buffetted by gusts of wind. Then, despite the raging tempest, Wasp lowered a boat at 0016, and brought the remaining four men aboard from the foundering 152-foot schooner soon thereafter.

Later that day, Wasp disembarked her rescued mariners and immediately went into dry dock at the Norfolk Navy Yard. The ship received vital repairs to her turbines. Port holes on the third deck were welded over to provide better watertight integrity, and steel splinter shielding around her 5-inch and 1.1-inch batteries was added. After those repairs and alterations were finished, Wasp got underway for the Virgin Islands on 22 March 1941, the carrier arriving at St. Thomas three days later. She soon shifted to Guantanamo Bay and loaded marine stores for transportation to Norfolk.

Returning to Norfolk on 30 March 1941, Wasp conducted routine flight operations out of Hampton Roads over the ensuing days, into April. In company with Sampson (DD-394), the carrier conducted an abortive search for a downed patrol plane in her vicinity on 8 April. For the remainder of the month, Wasp operated off the eastern seaboard between Newport, R.I., and Norfolk, conducting extensive flight and patrol operations with her embarked air group. She shifted to Bermuda in mid-May, anchoring at Grassy Bay on the 12th. Eight days later, the ship got underway in company with Quincy (CA-39), Livermore (DD-429), and Kearny (DD-432) for exercises at sea before returning to Grassy Bay on 3 June. Wasp sailed for Norfolk three days later with Edison (DD-439) as her antisubmarine screen.

After a brief stay in the Tidewater area, Wasp headed back toward Bermuda on 20 June 1941. Wasp and her escorts patrolled the stretch of the Atlantic between Bermuda and Hampton Roads until 5 July, as the Atlantic Fleet's neutrality patrol zones were extended eastward. Reaching Grassy Bay on that day, she remained in port a week before returning to Norfolk, sailing on 12 July in company with Tuscaloosa, Grayson (DD-435), Anderson (DD-411), and Rowan (DD-405).

Following her return to Norfolk on the 13th, Wasp and her embarked air group conducted refresher training off the Virginia capes. Meanwhile, the situation in the Atlantic had taken on a new complexion, with American participation in the Battle of the Atlantic only a matter of time, when the United States took another step toward involvement on the side of the British. To protect American security and to free British forces needed elsewhere, the United States made plans to occupy Iceland. Wasp played an important role in the move.

Late on the afternoon of 23 July 1941, while the carrier lay alongside Pier 7, NOB Norfolk, 32 Army Air Force (AAF) pilots reported on board "for temporary duty." At 0630 the following day, Wasp's crew watched an interesting cargo come on board, hoisted on deck by the ship's cranes: 30 Curtiss P-40C's and three Stearman PT-17 trainers from the AAF 33rd Pursuit Squadron, 8th Air Group, Air Force Combat Command, home-based at Mitchell Field, N.Y. Three days later, four newspaper correspondents, including the noted journalist Fletcher Pratt, came on board.

The carrier had drawn the assignment of ferrying those vital army planes to Iceland because of a lack of British aircraft to cover the American landings. The U.S. P-40's would provide the defensive fighter cover necessary to watch over the initial increment of American occupying forces. Wasp consequently cast off from Pier 7 and slipped out to sea through the swept channel at 0932 on 28 July 1941, with O'Brien (DD-415) and Walke as plane guards. Heavy cruiser Vincennes (CA-44) later joined the formation at sea.

Within a few days, Wasp's group joined the larger Task Force (TF) 16-consisting of battleship Mississippi (BB-41), heavy cruisers Quincy and Wichita, five destroyers, auxiliary vessel [converted destroyer] Semmes (AG-24), transport American Legion (AP-35), storeship Mizar (AF-12), and cargo ship Almaack (AK-27). Those ships, too, were bound for Iceland with the first occupation troops embarked. On the morning of 6 August 1941, Wasp, Vincennes, Walke, and O'Brien parted company from TF 16. Soon thereafter, the carrier turned into the wind and commenced launching the planes from the 33rd Pursuit Squadron. As the P-40's and the trio of trainers droned on to Iceland, Wasp headed home for Norfolk, her three escorts in company. After another week at sea, the group arrived back at Norfolk on 14 August.

Underway again on 22 August 1941, however, Wasp put to sea for carrier qualifications and refresher landings off the Virginia capes. Two days later, Rear Adm. H. Kent Hewitt, Commander Cruisers, Atlantic Fleet, shifted his flag from light cruiser Savannah (CL-42) to Wasp, while the ships lay anchored in Hampton Roads. Underway on the 25th, in company with Savannah, Monssen (DD-436) and Kearny, the aircraft carrier conducted flight operations over the ensuing days. Scuttlebutt on board had her steaming out in search of a German heavy cruiser, Admiral Hipper, which was reportedly roaming the western Atlantic in search of prey. Suspicions were confirmed for many on the 30th when the British battleship HMS Rodney was sighted some 20 miles away, on the same course as the Americans.

In any event, if they had been in search of a German raider, they did not make contact with her. Wasp and her escorts anchored in the Gulf of Paria, Trinidad, on 2 September 1941, where Rear Adm. Hewitt shifted his flag back to Savannah. The carrier remained in port until 6 September, when she again put to sea on patrol "to enforce the neutrality of the United States in the Atlantic."

While at sea, the ship received the news of a German U-boat unsuccessfully attempting to attack the destroyer Greer (DD-145). The United States had been getting more and more involved in the war; American warships were now convoying British merchantmen halfway across the Atlantic to the "mid-ocean meeting point" (MOMP).

Lieutenant David McCampbell, USN, Landing Signal Officer, bringing in planes, circa late 1941 or early 1942. Behind him is George E. Doc Savage, USN, Assistant Landing Signal Officer. In catwalk, foreground, are Len Ford (an enlisted man), USN, and Lieutenant Hawley Russell, USN. Note F4F Wildcats in background, overhead. Caption information provided by Captain David McCampbell, USN (Retired) in 1982. Official U.S. Navy photograph now in the collections of the National Archives, 80-G-K-688.

Wasp's crew looked forward to returning to Bermuda on 18 September 1941, but the new situation in the Atlantic meant a change in plans. Shifted to the colder climes of Newfoundland, the carrier arrived at Placentia Bay on 22 September and fueled from the oiler Salinas (AO-19) the following day. The respite in port was a brief one, however, as the ship got underway again, late on the 23d, for Iceland. In company with Wichita, four destroyers, and the repair ship Vulcan (AR-5), Wasp arrived at Hvalfjordur, Iceland, on the 28th. Two days earlier, Adm. Harold R. Stark, the Chief of Naval Operations, had ordered U.S. warships to do their utmost to destroy whatever German or Italian warships they found. The "short-of-war" operations were drawing frightfully close to the real thing.

With the accelerated activity entailed in the U.S. Navy's conducting convoy escort missions, Wasp put to sea on 6 October 1941 in company with Vincennes and four destroyers. Those ships patrolled the foggy, cold, North Atlantic until returning to Little Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, on the 11th, anchoring during a fierce gale that lashed the bay with high winds and stinging spray. On 17 October, Wasp set out for home (Norfolk) patrolling en route, and arrived at her destination on the 20th. The carrier soon sailed for Bermuda and conducted qualifications and refresher training flights en route. Anchoring in Grassy Bay on 1 November, Wasp operated on patrols out of Bermuda for the remainder of the month.

October had seen the incidents involving American and German warships multiplying on the high seas. Kearny was torpedoed on 17 October 1941; Salinas took a "fish" on the 28th; and in the most tragic incident that autumn, Reuben James (DD-245) was torpedoed and sunk with heavy loss of life on 30 October. Meanwhile, in the Pacific, tension between the United States and Japan increased almost daily.

Wasp slipped out of Grassy Bay on 3 December 1941 and rendezvoused with Wilson (DD-408). While the destroyer operated as plane guard, Wasp's air group flew day and night refresher training missions. In addition, the two ships conducted gunnery drills before returning to Grassy Bay two days later.

Wasp lay at anchor on 7 December 1941, observing "holiday routine," it being a Sunday. In the Pacific, the Japanese broke the Sunday morning peace in a devastating surprise attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor and nearby naval and military installations on Oahu. Their daring attack plunged the United States into World War II in both oceans. On 11 December, Germany and Italy followed Japan into war against the United States.

Meanwhile, U.S. naval authorities felt considerable anxiety that the Vichy French warships in the Caribbean and West Indies were prepared to make a breakout and attempt to get back to France. Accordingly, Wasp, light cruiser Brooklyn (CL-40), and two destroyers, Sterett (DD-407) and Wilson, departed Grassy Bay and headed for Martinique. Faulty intelligence gave American planners in Washington the impression that the Vichy French armed merchant cruiser Barfleur had gotten underway for sea. The French were accordingly warned that the auxiliary cruiser would be sunk or captured unless she returned to port and resumed her internment. As it turned out, Barfleur had not departed after all, but had remained in harbor. The tense situation at Martinique eventually dissipated, and the crisis abated.

With tensions in the West Indies lessened considerably, Wasp departed Grassy Bay and headed for Hampton Roads three days before Christmas of 1941, in company with the aircraft escort vessel Long Island (AVG-1), and escorted by Stack (DD-406) and Sterett. Two days later, the carrier moored at the Norfolk Navy Yard to commence an overhaul that would last into 1942.

After departing Norfolk on 14 January 1942, Wasp headed north and touched at Argentia, Newfoundland, and Casco Bay, Maine, while operating in those northern climes. On 16 March, as part of Task Group (TG) 22.6, she headed back toward Norfolk. During the morning watch the next day, visibility lessened considerably, however, and, at 0550, Wasp's bow plunged into Stack's starboard side, punching a hole and completely flooding the destroyer's number one fire room. Stack was detached and proceeded to the Philadelphia Navy Yard, where her damage was repaired.

Wasp, meanwhile, made port at Norfolk on the 21st without further incident. Shifting back to Casco Bay three days later, she sailed for the British Isles on 26 March 1942, with Task Force (TF) 39 under the command of Rear Adm. John W. Wilcox, Jr., in Washington (BB-56). That force was to reinforce the Home Fleet of the Royal Navy. While en route, however, Rear Adm. Wilcox was swept overboard from the battleship and drowned. Although hampered by poor visibility conditions, Wasp planes took part in the search. Wilcox' body was spotted an hour later, face down in the raging seas, but it was not recovered.

Rear Adm. Robert C. Giffen, who flew his flag in Wichita, assumed command of TF-39. The U.S. ships were met by a force based around the light cruiser HMS Edinburgh on 3 April. Those ships escorted them to Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

While the majority of TF 39 joined the British Home Fleet, being renumbered to TF 99 in the process, to cover convoys routed to North Russia, Wasp departed Scapa Flow on 9 April 1942, bound for the Clyde estuary and Greenock, Scotland. On the following day, the carrier steamed up the Clyde, past the John Brown Clydebank shipbuilding facilities. There, workers paused long enough from their labors to accord Wasp a tumultuous reception as she passed. Wasp's impending mission was an important one, one upon which the fate of the island bastion of Malta hung. That key isle was then being pounded daily by German and Italian planes. The British, faced with the loss of air superiority over the island, requested the use of a carrier to transport planes that could wrest air superiority from the Axis aircraft. Wasp drew ferry duty once again.

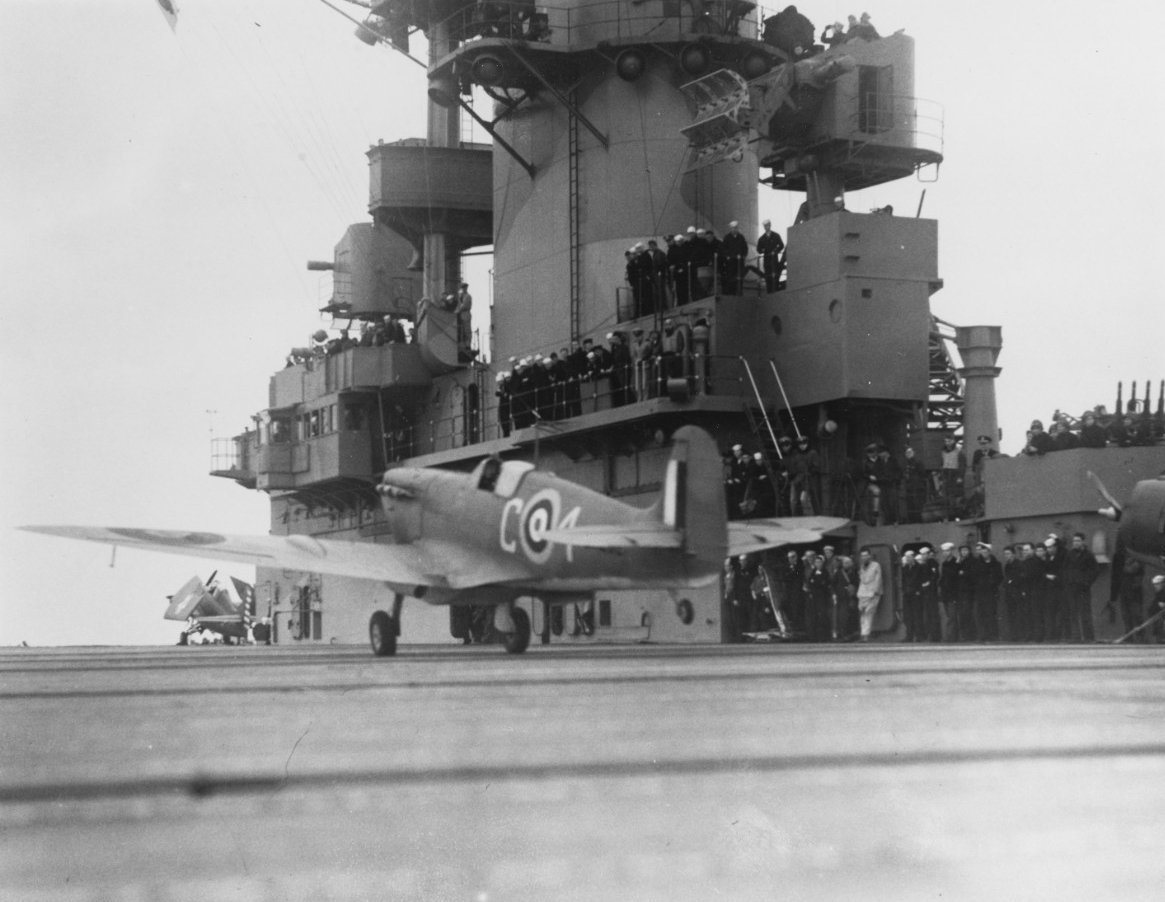

Having landed her torpedo planes and dive bombers, Wasp loaded 47 Supermarine Spitfire Mk. V fighter planes at the King George V Dock, Glasgow, on 13 April, before she departed the Clyde estuary on the 14th. Her screen consisted of Force "W" of the Home Fleet -- a group that included the battlecruiser HMS Renown and antiaircraft cruisers HMS Cairo and HMS Charbydis. Madison (DD-425) and Lang (DD-399) also served in Wasp's screen.

Wasp and her consorts passed through the Straits of Gibraltar under cover of the pre-dawn darkness on 19 April 1942, avoiding the possibility of being discovered by Spanish or Axis agents. At 0400 on 20 April, Wasp spotted 11 Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat fighters on her deck and quickly launched them to form a combat air partol (CAP) over Force "W". Meanwhile, the Spitfires were warming up their engines in the hangar deck spaces below. With the Wildcats patrolling overhead, the Spitfires were brought up singly on the after elevator, spotted for launch, and then given the go-ahead to take off. One by one, they roared down the deck and over the forward rounddown, until each Spitfire was aloft and winging toward Malta.

When the launch was complete, Wasp retired toward England, having safely delivered her charges. Unfortunately, those Spitfires, which flew in to augment the dwindling numbers of Gloster Gladiator and Hawker Hurricane fighters, were tracked by efficient Axis intelligence and their arrival pinpointed. The unfortunate Spitfires were decimated by heavy German air raids which caught many planes on the ground.

As a result, it looked as if the acute situation required a second ferry run to Malta. Accordingly, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, fearing that Malta would be "pounded to bits," asked President Roosevelt to allow Wasp to have "another good sting." Roosevelt responded in the affirmative. Rising to the occasion, Wasp loaded another contingent of Spitfire V's and sailed for the Mediterranean on 3 May. Again, especially vigilant for submarines, Wasp proceeded unmolested. This time, the British aircraft carrier HMS Eagle accompanied Wasp; and she, too, carried a contingent of Spitfires bound for Malta.

The two Allied flattops reached their launching points early on Saturday, 9 May 1942, with Wasp steaming in column ahead of Eagle at a distance of 1,000 yards. At 0630, Wasp commenced launching planes, 11 F4F-4's of VF-71 to serve as CAP over the task force. The first Spitfire roared down the deck at 0638, and 22 of the Spitfires took off with no difficulties. The twenty-third, however, piloted by Sergeant R. D. Sherrington, RAFVR, lost power soon after takeoff and plunged into the sea. Both pilot and plane were lost.

Misfortune again seemed to dog the mission when Pilot Officer (PO) Jerrold A. Smith discovered his long-range tank to be defective. Wasp – which had launched the last British aircraft at 0738 – bent on full speed and recovered Smith’s Spitfire Vc, X-3 (BR-126) at 0743. The Spitfire came to a stop just 15 feet from the forward edge of the flight deck, making what one Wasp sailor observed to be a "one wire" landing. “The pilot landed with considerable skill,” Commodore C. S. Daniel, Royal Navy, Commodore Commanding Force “W” later reported, “and immediately asked permission to fit a new tank, take off and proceed independently, but this was not allowed.” Wasp launched Smith the following day [10 May] to fly to Gibraltar; he ultimately reached embattled Malta in X-3 on 18 May, flying in from Eagle.

With Operation Bowery having been completed – Wasp having launched 47 Spitfires and Eagle 17 – Wasp set sail for the British Isles while a German radio station broadcast the startling news that the U.S. carrier had been sunk! Most in the Allied camp knew better, however, and, on 11 May 1942, Prime Minister Churchill sent a witty message to the captain and ship's company of Wasp: "Many thanks to you all for the timely help. Who said a Wasp couldn't sting twice?"

While Wasp was conducting those two important missions to Malta, a train of events far to the westward beckoned the carrier to the Pacific theater. Early in May, almost simultaneously with Wasp's second Malta run, Operation Bowery, the Battle of the Coral Sea had been fought. That action turned back the Japanese thrust at Port Moresby. One month later, from 4 to 6 June, an American carrier force smashed its Japanese counterpart in the pivotal Battle of Midway.

These two victories, however, cost the United States two precious carriers: Lexington (CV-2) at Coral Sea and Yorktown (CV-5) at Midway. While the Japanese had suffered the loss of a small carrier and the damaging of one fleet carrier at Coral Sea and the loss of four fleet carriers at Midway, the United States could scarcely afford to be left with only two operational carriers in the western and central Pacific -- Enterprise (CV-6) and Hornet (CV-8). Saratoga (CV-3) was still undergoing repairs and modernization after being torpedoed off Oahu in early January 1942.

To prepare to strengthen the U.S. Navy in the Pacific, Wasp was hurried back to the United States for alterations and repairs at the Norfolk Navy Yard. During the carrier's stay in the Tidewater region, Capt. Reeves, who had been promoted to flag rank, was relieved by Capt. Forrest P. Sherman on 31 May 1942. Departing Norfolk on 6 June, the last day of the critical Battle of Midway, Wasp sailed with TF 37 which was built around the carrier and the new battleship North Carolina (BB-55) and escorted by Quincy (CA-39) and San Juan (CL-54) and six destroyers. The group transited the Panama Canal on 10 June, at which time Wasp and her consorts became TF 18, the carrier flying the two-starred flag of Rear Adm. Leigh Noyes.

Arriving at San Diego on 19 June 1942, Wasp embarked the remainder of her complement of aircraft, Grumman TBF-l's and Douglas SBD-3's. 10 of the former and 12 of the latter conducting their carrier qualification on 22 and 23 June, respectively, the latter replacing the old Vindicators. On 1 July, she sailed for the Tonga Islands as part of the convoy for the five transports that had embarked the Second Marine Regiment.

While TF 18 and the transports were en route to Tongatabu, Wasp received another congratulatory message, this time from Adm. Noyes, embarked in the ship. "During the two weeks my flag has been in Wasp I have been very favorably impressed by the fine spirit of her ship's company and the way that all hands have handled their many problems. Since we have been at sea, every day has shown marked improvement in operations. I am sure that when our opportunity comes to strike the enemy in this ocean, Wasp and her squadrons will add more glory to the name she bears."

Four days out of Nukualofa harbor, however, Wasp developed serious engine trouble. The ship's "black gang" worked diligently to do the preliminary work in lifting, repairing, and replacing the ship's starboard high-pressure turbine. The work done en route substantially helped enough to allow speedy completion of the repairs after the ship dropped her hook at Tongatabu on 18 July 1942.

Meanwhile, preparations to invade the Solomon Islands were proceeding apace. Up to that point, the Japanese had been on the offensive, establishing their defensive perimeter of the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere." On 4 July 1942, while Wasp was en route to the South Pacific, the Japanese landed on Guadalcanal. Allied planners realized that if the enemy operated land-based aircraft from that key island, then it immediately imperiled Allied control of the New Hebrides and New Caledonia area. Rather than wait until the Japanese were firmly entrenched, they proposed to evict the Japanese before they got too deeply settled. Vice Adm. Robert L. Ghormley -- who had achieved a sterling record in London as Special Naval Observer -- was detailed to take command of the operation; and he established his headquarters at Auckland, New Zealand. Since the Japanese had gotten a foothold on Guadalcanal, time was of the essence. Preparations for the invasion proceeded apace with the utmost secrecy and speed.

Wasp, together with the carriers Saratoga and Enterprise, was assigned to the Support Force under Vice Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher, victor of Coral Sea and Midway. Under the tactical command of Rear Adm. Noyes, embarked in Wasp, the carriers were to provide air support for the invasion.

Wasp and her airmen worked intensively practicing day and night operations to hone their skills to a high degree. Pilot qualification and training, necessitated by the ship's recent operations in the Atlantic and by the re-equipment of her air group and newer types of planes, proceeded at an intensive pace and, by the time the operations against Guadalcanal were pushed into high gear, Capt. Sherman was confident that his airmen could perform their mission. "D-day" had originally been set for 1 August 1942, but the late arrival of some of the transports carrying marines pushed the date to 7 August.

Wasp, screened by heavy cruisers San Francisco (CA-38) and Salt Lake City (CA-25), and four destroyers, steamed westward toward Guadalcanal on the evening of 6 August 1942 until midnight. Then, she changed course to the eastward to reach her launch position 84 miles from Tulagi one hour before the first rays of sunlight crept over the horizon. A fresh breeze whipped across the carrier's darkened flight deck as the first planes were brought up to prepare for launch. The night offshore was bright, but clouds hung heavily over the assigned objective. So far, so good. No Japanese patrols had been spotted.

At 0530, the first planes from Wasp's air group barreled down the deck: 16 F4F-4's under Lt. Cmdr. Courtney Shands. Then, 15 SBD-3's under Lt. Cmdr. John Eldridge, Jr. and, the Avenger having been fitted with a larger gasoline tank in its bomb bay to lengthen its time in the air, the Grumman TBF-1 flown by Lt. Cmdr. Wallace M. Beakley, the air group commander, followed seven minutes later. At 0557, the first combat air patrol fighter took off.

The early flights of F4F's and SBD's were assigned specific targets: Tulagi, Gavutu, Tanambogo, Halayo, Port Purvis, Haleta, Bungana, and the radio station dubbed "Asses' Ears." After taking off, the 16 Wildcats split up into sections and raced off to their respective hunting areas. At about 0600, the planes passed over the transport area off Lunga Point, as the ships were preparing to disembark their troops. In the pre-dawn darkness, the ships were almost invisible until the fighters passed directly over them. Soon, the fourth division of Shands' flight climbed to 5,000 feet above Tulagi to serve as CAP for the strafers. The third division broke off and headed for their target -- Haleta -- before Shands took three planes around the northwest tip of Tulagi.

Shands and his wingman, Ens. S. W. Forrer, then swung down the north coast toward Gavatu. The other two headed for Tanambogo, to work over the seaplane facilities there. The Japanese appeared to be caught flat-footed, and the Grummans, arriving simultaneously at daybreak, shot up all of the patrol planes and fighter-seaplanes that were in the area. Fifteen Kawanishi flying boats and seven Nakajima floatplane fighters, the seaplane derivative of the Mitsubishi Zero, were destroyed by Shands' fighters that flew almost "on the deck." Shands himself bagged at least four Nakajima single-float fighter seaplanes and one four-engined flying boat. His wingman, Forrer, bagged three floatplane fighters and one patrol plane; Lt. Wright and Ens. Kenton bagged three patrol planes apiece and destroyed a motorboat apparently attempting to tend the flying boats; Ensigns Reeves and Conklin each bagged two and shared a fifth patrol plane between them. In addition, the strafing F4Fs destroyed an aviation fuel truck and a truck loaded with spare parts.

The SBD's, too, laid their bombs "on the money." Post-attack assessment estimated that the antiaircraft and shore battery sites pinpointed by intelligence had been destroyed by the dive bombers in their first attack. So complete was the enemy's unpreparedness that none of Wasp's planes was shot down. Only one plane from the 16 Grummans failed to return; and, in that case, its pilot, Ensign Reeves, put her down on board Enterprise after having run low on fuel.

That was not all, however. At 0704, 12 Grumman TBF-ls, led by Lt. Henry A. Romberg, rolled ponderously down the deck, loaded with bombs for use against land targets. Having encountered resistance, the initial landing forces called for help. Romberg's dozen Avengers blasted enemy troop concentrations east of the nob of land known as Hill 281, in the Makambo-Sasapi sector, and the prison on Tulagi Island. "All enemy resistance," the official report later stated, was "apparently effectively silenced by this flight."

The first day's operations against Guadalcanal had proved successful. Some 10,000 men had been put ashore there and met only slight resistance. On Tulagi, however, the Japanese resisted stoutly, retaining about one-fifth of the island by nightfall. Wasp, Saratoga, and Enterprise, with their screens, retired to the southward at nightfall.

Wasp returned the next morning, 8 August 1942, to maintain a continuous CAP over the transport area until noon. These fighters were led by Lt. Charles S. Moffett. Meanwhile, she also launched a scouting flight of 12 SBD-3s led by Lt. Cmdr. E. M. Snowden. The Dauntlesses searched a sector to a radius of 220 miles from their carrier, extending it to include all of the Santa Isabel Island and the New Georgia group.

The Dauntless pilots sighted nothing that morning and made no contact with the enemy during their two hours in the air. But that was soon to change for the flight leader. At 0815, Snowden sighted a floatplane fighter some 40 miles from Rekata Bay and gave chase. The Japanese pilot, seeing that he had been spotted, pulled up and attempted to use the clouds for cover. Each time the dogged dive bomber pilot gunned the SBD-3 after him: twice the Japanese headed for the clouds. Snowden finally pulled within close range, and, using his two fixed .50-caliber guns, fired a short burst that hit home, causing the floatplane to spin into the Solomon Sea.

Meanwhile, a large group of Japanese planes approached from Bougainville, apparently bent upon attacking the transports off Lunga Point. Upon learning of their approach, Rear Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner ordered all transports to get underway and to assume cruising disposition. The Americans accordingly cleared the decks for action. Wasp's planes took part in the melee that followed -- some planes almost by accident.

Lt. Cmdr. Eldridge. again leading a formation of SDB-3s from VS-71, had led his planes against Mbangi Island, off Tulagi, the site of some still fierce Japanese resistance. Eldridge's rear seat gunner, ACR L. A. Powers, suddenly spotted a formation of planes coming in from the northeast, but, thinking them to be a relief flight, Eldridge continued on his present course. The Americans did a double take, however, and discovered that the planes were, in fact, enemy. At that instant, six Zeroes showed up and bounced the first section, but showed remarkably little skill in the attack, for they made 12 firing passes but could not down any of the Dauntlesses.

Meanwhile, the leader of the last section of VS-71, Lt. (j.g.) Robert L. Howard, spotted a cluster of twin-engined Mitsubishi G4M1 Type 1 land attack planes (later nicknamed Betty) heading for the American transports. Howard dove to the attack; but, in his excitement, failed to flip his armament switch to "on." After two runs during which his guns had failed to fire, thinking that the guns needed to be recharged, he discovered his error, but too late to do anything about the Mitsubishis. At that moment, four Zeroes, escorts for the bombers, attacked the single SBD.

Howard's radio gunner, Sea2c Lawrence P. Lupo, handled his twin 30-caliber mount magnificently and kept the enemy fighters at arm's length, his bullets scoring several hits on them as well. After about eight passes, one Zero veered up sharply and made a head-on run that Howard met with simultaneous fire from his fixed .50's. The Zero caught fire like a flying tinder box, passed close aboard the Dauntless' left wing, and crashed in flames amidst the American landing craft far below. At the same time Howard was downing the Zero ahead, Sea2c Lupo was firing on another Zero making an attack from the stern. Lupo kept the enemy away, but he had to shoot through his own plane's vertical stabilizer to do it. Eventually, the enemy tired of sporting with the SBD and retired to leave Howard and his squadron mates in VS-71 to return safely to their carrier.

At 1807 on 8 August 1942, Vice Adm. Fletcher recommended to Ghormley, at Noumea, that the air support force be withdrawn. Fletcher, concerned by the large numbers of enemy planes that had attacked on the 8th, reported that he had only 78 fighters left (he had started with 99) and that fuel for the carriers was running low. Ghormley approved the recommendation, and Wasp joined Enterprise and Saratoga in retiring from Guadalcanal. By midnight on 8 August, the landing had been a success, having attained the immediate objectives of the landing. All Japanese resistance, but a few snipers, on Gavutu and Tanombogo had been overcome.

Scene on Wasp's (CV-7) port bridge wing during operations off Guadalcanal on 7 August 1942. Among those present are (from left to right, in the right center) Commander D.F. Smith (hatless); Captain Forrest P. Sherman, Commanding Officer (wearing helmet); Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes, Commander Task Group 61.1 (facing camera); and Lieutenant Commander Wallace M. Beakley, Commander Wasp Air Group, who is making his report to Rear Admiral Noyes. Official U.S. Navy photograph now in the collections of the National Archives, 80-G-16864.

Early on 9 August 1942, however a Japanese surface force, under Vice Adm. Mikawa Gunichi, engaged an American one off Savo Island and retired at very little cost to themselves. The Allied force suffered loss of four heavy cruisers off Savo Island, including two that had served with Wasp in the Atlantic: Vincennes and Quincy. The early and unexpected withdrawal of the support force, including Wasp, when coupled with Allied losses in the Battle of Savo Island, jeopardized the success of the operation in the Solomons.

After the initial day's action in the Solomons campaign, the carrier spent the next month engaged in patrol and covering operations for convoys and resupply units headed for Guadalcanal. The Japanese, while reacting sluggishly to the initial thrust at Guadalcanal, soon began pouring reinforcements down to contest the Allied forces.

Wasp was ordered south by Vice Adm. Fletcher to refuel and thus did not participate in the Battle of Eastern Solomons on 24 August 1942. That engagement cost the U.S. force the use of Enterprise. Saratoga was torpedoed a week later and departed the South Pacific war zone for repairs as well. That left only two carriers in the southwest Pacific: Hornet, which had been in commission for only a year, and Wasp.

On Tuesday, 15 September 1942, those two carriers and North Carolina, with ten other warships, were escorting the transports carrying the Seventh Marine Regiment to Guadalcanal as reinforcements. Wasp had drawn the job of ready-duty carrier and was operating some 150 miles southeast of San Cristobal Island. Her gasoline system was in use, as planes were being refueled and rearmed for antisubmarine patrol missions; and Wasp had been at general quarters from an hour before sunrise until the time when the morning search returned to the ship at 1000. Thereafter, the ship was in condition 2, with the air department at flight quarters. There was no contact with the enemy during the day, with the exception of a Japanese four-engined flying boat downed by a Wasp Wildcat at 1215.

About 1420, the carrier turned into the wind to launch eight fighters and 18 SBD-3s and to recover eight F4F-3s and three SBDs that had been airborne since before noon. The ship rapidly completed the recovery of the 11 planes; she then turned easily to starboard, the ship heeling slightly as the course change was made. The air department at flight quarters, as they had done in earlier operations, worked coolly at refueling and respotting the ship's planes for the afternoon mission. Suddenly, at 1444, a lookout called out, "three torpedoes . . . three points forward of the starboard beam!"

A spread of four torpedoes, fired from the tubes of the Japanese submarine I-19, churned inexorably closer. Wasp put over her rudder hard-a-starboard, but it was too late. Two torpedoes smashed home in quick succession while a fourth passed ahead. Both hit in the vicinity of gasoline tanks and magazines.

In quick succession, fiery blasts ripped through the forward part of the ship. Aircraft on the flight and hangar decks were thrown about as if they were toys and dropped on the deck with such force that landing gears snapped. Planes triced up in the hangar overheads fell and landed upon those on the hangar deck; fires broke out almost simultaneously in the hangar and below decks. Soon, the heat of the intense gasoline fires detonated the ready ammunition at the forward antiaircraft guns on the starboard side; and fragments showered the forward part of the ship. The number two 1.1-inch mount was blown overboard and the corpse of the gun captain was thrown onto the bridge where it landed next to Capt. Sherman.

Water mains in the forward part of the ship proved useless, since they had been broken by the force of the explosions. There was no water available to fight the conflagration forward; and the fires continued to set off ammunition, bombs, and gasoline. As the ship listed to starboard between 10 and 15 degrees, oil and gasoline, released from the tanks by the torpedo hit, caught fire on the water.

Sherman slowed to 10 knots, ordering the rudder put to port to try to get the wind on the starboard bow; he then went astern with right rudder until the wind was on the starboard quarter, in an attempt to keep the fire forward. At that point, some flames made central station untenable, and communication circuits went dead. Soon, a serious gasoline fire broke out in the forward portion of the hangar; within 24 minutes of the initial attack, three additional major gasoline vapor explosions occurred. Ten minutes later, Capt. Sherman consulted with his executive officer, Cmdr. Fred C. Dickey. The two men saw no course but to abandon, as all fire-fighting was proving ineffectual. The survivors would have to be gotten off quickly if unnecessary loss of life was not to be incurred.

Reluctantly, after consulting with Rear Adm. Noyes, Capt. Sherman ordered "abandon ship" at 1520. All badly injured men were lowered into rafts or rubber boats. Many unwounded men had to abandon from aft because the forward fires were burning with such intensity. The departure, as Capt. Sherman observed it, looked "orderly," and there was no panic. The only delays occurred when many men showed reluctance to leave until all the wounded had been taken off. The abandonment took nearly 40 minutes; and, at 1600, satisfied that no one was left on deck, in the galleries, or in the hangar aft, Capt. Sherman swung over the lifeline on the fantail and slid into the sea.

Although the submarine hazard caused the accompanying destroyers to lie well clear or to shift position, Laffey (DD-459), Lansdowne (DD-486), Farenholt (DD-491), Lardner (DD-487), and Duncan (DD-485) carried out the rescue efforts with persistence and determination. The abandoned carrier drifted with her dead. The fires worked their way aft; four more violent explosions boomed as night began to fall. Of her ship's company, marine detachment, and embarked air group, the dead numbered 25 officers and 150 men; in addition, Jack Singer, an International News Service correspondent, died in the disaster.

Lansdowne drew the duty of destruction, and she fired five torpedoes into the dying ship's gutted hull. Three hit, but she remained afloat. By now, the orange flames had enveloped the stern. The carrier literally floated in a burning pool of gasoline and oil. She sank at 2100 by the bow.

In the wake of Wasp's loss, Capt. Sherman praised the commanding officers of the five destroyers that rescued his men. "Their task," Sherman wrote, "required the nicest judgment in seamanship and required that their ships be stopped for considerable periods while many seriously wounded casualties were laboriously taken aboard [sic]. The limited facilities of the Duncan and Lansdowne in particular were stretched almost to the breaking point in an attempt to support life in the gravely wounded and to make all others as comfortable as possible during the passage to port."

Wasp received two battle stars for her World War II service.

Commanding Officers |

Dates of Command |

Capt. John W. Reeves, Jr. |

25 April 1940–31 May 1942 |

Capt. Forrest P. Sherman |

31 May 1942–15 September 1942 |

Robert J. Cressman

Updated 20 April 2018