Kitkun Bay (CVE-71)

1943–1946

A bay on the southeast coast of Prince of Wales Island in the Alexander Archipelago of Alaska.

(CVE-70: displacement 7,800; length 512'3"; beam 65'2"; extreme width 108'1"; draft 22'6"; speed 19 knots; complement 860; armament 1 5-inch, 16 40-millimeter, 20 20-millimeter; aircraft 27; class Casablanca, type S4-S2-BB3)

Kitkun Bay was authorized under a Maritime Commission contract (M.C. Hull 1108); subsequently classified as an aircraft escort vessel (AVG-71); and reclassified to an auxiliary aircraft carrier (ACV-71) on 20 August 1942. The ship was laid down on 3 May 1943, by Kaiser Shipbuilding Co., at Vancouver, Wash.; named Kitkun Bay on 28 June 1943; reclassified to an escort aircraft carrier (CVE-70) on 15 July 1943; launched on 8 November 1943; sponsored by Mrs. Francis E. Cruise, née Crane, wife of Capt. Edgar A. Cruise, Chief of Staff, Commandant, Fleet Air, Naval Air Station (NAS) Seattle, Wash., and a recipient of the Navy Cross for his valor against the Japanese during the fighting off Guadalcanal in the Solomons in August 1942; and commissioned on 15 December 1943 at NAS Astoria, Ore., Capt. John P. Whitney in command.

Japanese submarine I-25 had shelled the Army’s Fort Stevens, located at the mouth of the Columbia River, Ore., on the night of 21–22 June 1942. The enemy raid caused minimal damage but alarums continued for some time. While Kitkun Bay fitted out moored to Pier 1 at NAS Astoria at 0420 on the morning of 3 January 1944, an unidentified aircraft flew over the area. The ship sounded general quarters for the first time in earnest, only to discover a U.S. plane that evidently failed to acknowledge recognition protocol.

Kitkun Bay then carried out a shakedown cruise in the Puget Sound area, a voyage which included loading bombs and ammunition, fueling, compass calibration, and deperming—reducing the magnetism of iron to help protect vessels from magnetic mines. The carrier stood out of Seattle harbor on 13 January 1944, briefly stopped at Port Townsend, rounded the Olympic Peninsula and turned southward. Kitkun Bay loaded fuel, ammunition, and aircraft equipment at NAS Alameda, Calif. (17–20 January), and then resumed her southward voyage, carrying out gunnery practice until she slipped into San Diego, Calif., on the 22nd. Through the 27th, the ship stood down the channel, rounded NAS San Diego on North Island, and headed back to sea for torpedo and additional gunnery exercises. While she did so, Composite Squadron (VC) 5, the squadron earmarked to operate from her, trained with 12 Eastern FM-2 Wildcats, seven Eastern TBM-1 Avengers, and a pair of Grumman TBF-1 Avengers at Naval Auxiliary Air Station (NAAS) Ream Field in Imperial Beach, Calif.

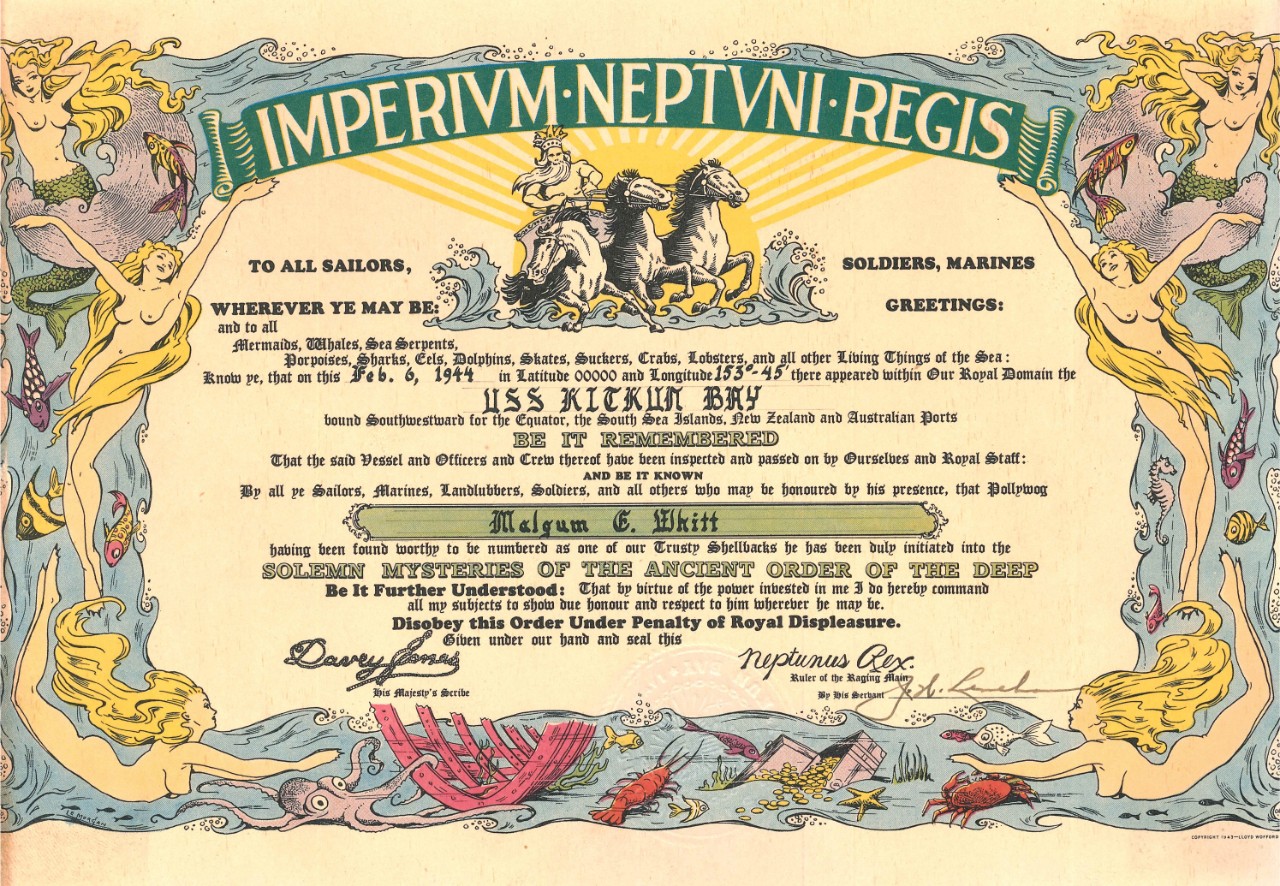

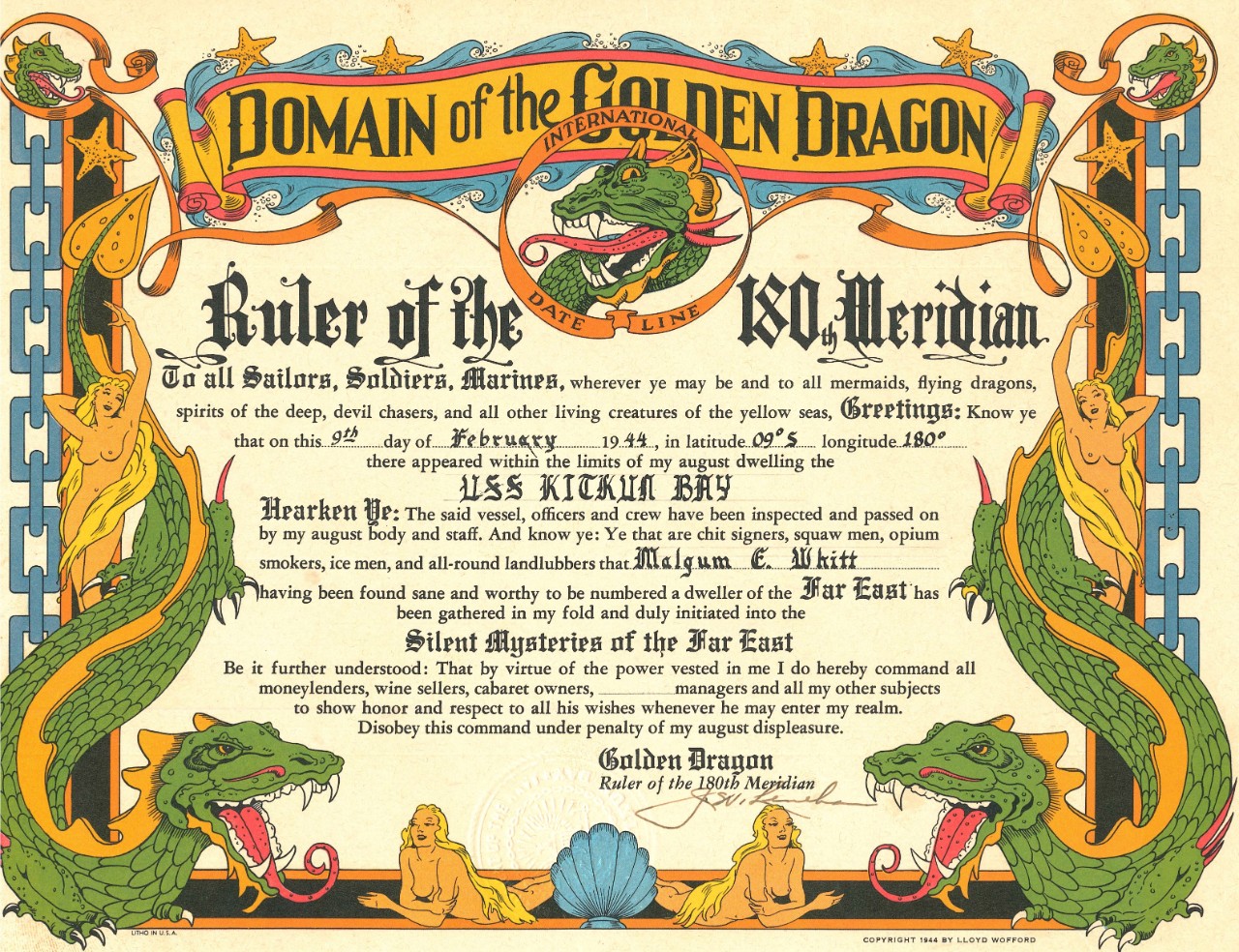

The ship embarked 13 naval officers destined for other commands, and loaded 17 TBF-1s and their marine crews and maintainers of Marine Torpedo Bomber Squadron (VMTB) 242 (27–28 January 1944), and stood out of San Diego on a replenishment voyage to the Allied garrison on Espíritu Santo in the New Hebrides [Vanuatu]. Kitkun Bay steamed independently, and carried out drills and instruction periods, as well as almost daily antiaircraft practice. The escort carrier crossed the equator at 153°45'W on 6 February, and three days later sighted some of the Samoan islands and crossed the 18th meridian. The ship neared waters in which the Allies believed Japanese submarines still prowled, and so escort ship Loeser (DE-680), Lt. Cmdr. Chester A. Kunz in command, rendezvoused with the carrier that day and shepherded her the rest of the way to the New Hebrides. Lookouts sighted Lopevi and Pentecost Islands on 14 February, and that evening the two ships entered Pallikula Bay, Espíritu Santo.

During the next two days, the 13 officer passengers and the marines disembarked, and the ship unloaded spare parts for that squadron and others deployed to the islands. Kitkun Bay shifted to Segond Channel on the 17th, where she took on fuel, mail, passengers, and miscellaneous gear, and the following day turned for Havannah harbor on nearby Efate, conducting firing exercises en route. High speed minesweeper Southard (DMS-10) escorted the carrier as the two ships charted a course for home via Ford Island at Pearl Harbor, T.H. (19–28 February), where they disembarked passengers and unloaded gear. From Hawaiian waters Kitkun Bay set sail to the eastward in company with Gambier Bay (CVE-73), which had delivered 84 replacement planes to aircraft carrier Enterprise (CV-6) and shore establishments, and was ferrying aircraft for repairs and qualified carrier pilots to the west coast, and the two escort carriers returned to San Diego on 6 March.

Upon her return, the ship loaded planes and men of VC-5 for training and assignment on 8 March 1944, and then (9–17 March) the pilots qualified on board her in southern Californian waters. Destroyer seaplane tender Ballard (AVG-10) acted as a plane guard during the exercises. Upon Kitkun Bay’s return to port, VC-5 went ashore for further training, while the carrier returned to sea and facilitated carrier qualifications for pilots from other squadrons through the end of the month. The ship then (1–27 April) accomplished repairs and upkeep at Naval Repair Base San Diego. While she lay there on the 21st, Rear Adm. Harold B. Sallada, Commander, Carrier Division (CarDiv) 26 broke his flag in the carrier.

Kitkun Bay spent the last days of the month back at sea checking her navigation instruments and conducting drills, before returning to port and loading aircraft, weapons, provisions, and passengers for further transfer to Pearl Harbor. Kitkun Bay sailed with 12 FM-2 Wildcats and nine TBM-1C Avengers of VC-5, and, in company with the rest of the carrier division, Gambier Bay and Nehenta Bay (CVE-74), screened by destroyers Heyward L. Edwards (DD-663) and Monssen (DD-798) on either side of the formation, turned westward (1–8 May) and again moored at Ford Island.

Kitkun Bay and VC-5 completed more carrier qualifications off Oahu, interrupted by upkeep at Ford Island, and followed by further training at sea in company with battleship Maryland (BB-46) (10–11, 12–15, and 16–19 May, respectively). Another upkeep period gave the ship a chance to prepare for Operation Forager—amphibious landings in the Japanese-held Marianas Islands.

Benham (DD-796), Laws (DD-558), and Morrison (DD-560) escorted Gambier Bay and Kitkun Bay as they cleared Pearl Harbor on 31 May 1944. They spent most of the day holding flight operations and that afternoon joined a bombardment group comprising California (BB-44), Colorado (BB-45), Maryland, and Tennessee (BB-43), screened by another dozen destroyers, and steaming with the vessels of Transport Division 16. The carriers launched Wildcats that flew daily combat air patrol (CAP) to protect their charges, and sent Avengers aloft that hunted for enemy submarines as the task unit chartered westerly courses into contested waters.

Lt. Robert E. Curtis of VC-5 flew a Wildcat (BuNo 16277) from Kitkun Bay but crashed on 1 June 1944, and a destroyer rescued the shaken pilot. Lt. (j.g.) Malcolm Lawty, USNR, piloted an Avenger (BuNo 45458) from the squadron on 4 June. Lawty approached the carrier to land but the landing signal officer (LSO) waved him off because the ship was still swinging into the wind. The torpedo bomber lost flying speed and side slipped into the water about 25 yards off Kitkun Bay’s starboard quarter. The gunner escaped from the plane but Lawty and his radioman went down with the aircraft. Morrison picked up the gunner and returned him to the carrier the following day. Kitkun Bay crossed the International Date Line (5–6 June) and dropped anchor in Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands on the 8th. The following day, the ship sounded general quarters three times because of U.S. planes that failed to properly identify themselves.

On 10 June 1944, she sortied from that atoll as part of Fire Support Group 1, Task Group (TG) 52.17, Rear Adm. Jesse B. Oldendorf, Commander Cruiser Squadron 4 and Bombardment Group 1, who wore his flag in heavy cruiser Louisville (CA-28). Once again, Kitkun Bay launched Wildcats and Avengers that flew CAP and antisubmarine patrols, respectively, at intervals, on their voyage toward the Marianas. The ship reported 12 FM-2s and eight TBM-1Cs of VC-5 on board on the 13th.

An Avenger flying from Kitkun Bay spotted an apparent periscope and dropped two bombs, at 0853 on 13 June. The ship made an emergency turn, the plane dropped a smoke bomb to mark its prey, and a pair of destroyers and another torpedo bomber attacked the area, but to no effect. The morning passed eventfully for the harried ship’s company and she vectored the CAP to a “bogey” (unidentified aircraft) about 20 miles to the east at 1048. At 1105, the four Wildcats intercepted the snooper, which turned out to be a Japanese Mitsubishi G4M1 Type 1 land attack plane, and splashed the Betty. The ship’s historian observed that news of the ship’s victory caused “justified jubilation” among her crew. The busy day finished as Melvin (DD-680) fired at an unknown surface contact at 2225—with the only known result that it did not reappear.

Gambier Bay and Kitkun Bay and a trio of destroyers detached just before midnight and during the mid watch at 0245 on 14 June, sighted flashes of gunfire and white flares on the horizon ahead, signifying the first evidence to the ship of the action on Saipan. At daybreak, the five ships rendezvoused with Coral Sea (CVE-57) and Corregidor (CVE-58) and their screening destroyers as part of Bombardment Group 2. As Kitkun Bay prepared to launch her early morning group, a rocket attached to the wing of a torpedo bomber discharged unexpectedly and hurtled past S2c Joseph V. Perry, USNR, one of the plane handlers, as he pushed the aircraft into position, injuring him about the head, shoulders, and chest. Perry died from his wounds (“multiple, extreme”) the following day. The ship nevertheless launched a dozen Wildcats and a pair of Avengers beginning at 0518, and they flew over the western beaches and observed surf conditions for the landings. Kitkun Bay sent additional aircraft aloft that morning and afternoon, and they flew CAP and provided smoke over some of the transports.

Kitkun Bay steamed off the eastward side of Saipan as part of Task Unit (TU) 52.11.1 while she launched ten Wildcats and seven Avengers that flew close air support for marines as they landed on Saipan on 15 June 1944. Throughout the day, the planes fired rockets and strafed the Japanese gun emplacements and troop positions on the beaches. The enemy shot down Lt. Joe F. Richardson Jr., USNR, of VC-5 as he flew a Wildcat (BuNo 16295) from Kitkun Bay, but Richardson escaped without serious injuries and Morrison picked him up.

Forager penetrated the inner defensive perimeter of the Japanese Empire and triggered A-Go—a Japanese counterattack that led to the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Their First Mobile Fleet, Vice Adm. Ozawa Jisaburō in command, included carriers Taihō, Shōkaku, Zuikaku, Chitose, Chiyōda, Hiyō, Junyō, Ryūhō, and Zuihō. The Japanese intended for their shore-based planes to cripple the air power of Task Force (TF) 58, Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher, in order to facilitate Ozawa’s strikes—which were to refuel and rearm on Guam. Japanese fuel shortages and inadequate training bedeviled A-Go, however, and U.S. signal decryption breakthroughs enabled attacks on Japanese submarines that deprived the enemy of intelligence. Raids on the Bonin and Volcano Islands furthermore disrupted Japanese aerial staging en route to the Marianas, and their main attacks passed through U.S. antiaircraft fire to reach the carriers.

Bogeys continued to appear on ship’s radar screens on 16 June 1944, and at 0307 a Japanese plane approached Kitkun Bay from seven miles out and the ship’s company manned their battle stations. The intruder came about and escaped, and so the crew secured from general quarters at 0341, but 18 minutes later more enemy planes threatened the task unit and Kitkun Bay’s weary men raced to their battle stations again. The ship launched Wildcats as CAP and Avengers to hunt for submarines, a pattern that she continued throughout the day. Morrison detected a submarine contact at 1345 that afternoon and dropped depth charges without results. Japanese aircraft made what the ship’s historian described as “their usual evening appearance” at 1850, and she sounded general quarters again until the threat passed.

Kitkun Bay operated about 30 miles east of Saipan with TU 52.11.1 as the sun rose on 17 June 1944. At 0518, the warship began launching the first of her planes for the day’s fighting, and as the watches progressed through the day, her Wildcats and Avengers bombed and strafed the enemy ashore, and flew CAP and antisubmarine patrols. Japanese fire damaged the wing flaps of a TBM-1C (BuNo 16804) flying from Kitkun Bay, and the Avenger splashed down into the water but Bryant (DD-665) retrieved the crew. Ens. Jack L. Krouse, USNR, crashed in a fighter (BuNo 16296) he piloted from the ship but was rescued.

The vessels of the task unit joined up and went to general quarters to repel an aerial attack which they expected to develop from bogeys on the radar screens flying at an altitude of 18,000 feet and at a range of about 50 miles from the formation. The carriers launched fighters to intercept the Japanese planes and the ships formed an antiaircraft cruising disposition. The sun began to set and the action around Kitkun Bay became too intense for the watchstanders to focus on the interceptors. Two Japanese dive bombers emerged from the clouds from about 3,000 feet and Kitkun Bay’s antiaircraft guns opened fire at them. One of the planes dropped a bomb that splashed close aboard Gambier Bay’s port bow, near No. 44 gun, and water from the attack rose up over the mount and onto the flight deck, but the defenders shot down both of the attackers.

“They are coming in high and dead ahead,” Gambier Bay logged ominously at 1849 as other aircraft roared past Gambier Bay’s port side and released two bombs that splashed just astern as she heeled over in turbulent turns zig-zagging, guns blazing. Four Japanese torpedo bombers approached Kitkun Bay from her port bow at 1850. The planes flew through the withering antiaircraft fire and close to the water as they bore in on the ship, and one of the assailants dropped a torpedo that passed astern of the formation. Gunfire splashed all four bombers, though the spotters could not discern which ship claimed which plane through the confusion. An all too brief lull ensued, and then Wildcats pursued and shot down two more enemy planes that attacked the ships. Another pair of dive bombers dived on the group at 1905, but intense antiaircraft fire compelled them to turn away.

All but one of the CAP fighters landed on board Kitkun Bay by 2026 on the 17th. Lt. Harry L. Cole Jr., USNR, of VC-5 flew the last Wildcat (BuNo 46913) but approached too low, and his tail hook caught on the handrail on the after ramp. The plane careened up the flight deck and over the starboard side, just abaft the island. A destroyer searched unsuccessfully throughout the night for the pilot.

Enemy planes sent the ships to general quarters at 0421 on 18 June 1944, but they turned out to be snoopers and did not press their attack. Kitkun Bay launched her planes for additional runs against Japanese troops on Saipan and nearby Tinian throughout the day. Radar detected a force of about 30 enemy aircraft approaching from 40 miles to the southward at 1603. As the attackers closed the range rapidly, the crew manned their battle stations, but the enemy kept off at a distance. Wildcats intercepted and splashed two planes at 1755, which fell burning into the sea about five miles from the ship.

Six Japanese planes suddenly approached the formation from the south at about 10,000 feet and all the ships opened fire as soon as they flew within range. An enemy plane, tentatively (and possibly erroneously) identified as a Nakajima J1N1 Gekko made a run on Kitkun Bay on her starboard bow. The Irving delayed releasing its torpedo and the ship’s forward starboard guns poured fire into the plane, and at 100 yards one of its engines began smoking. The attacker dropped the torpedo but it missed the carrier by about 25 feet since the captain had her in a sharp turn. As the Irving crossed the bow its tail gunner attempted to strafe the ship but several 20 millimeter shells sliced into him. Additional 40 millimeter rounds hit the plane and it burst into flames, rose vertically for about 1,000 feet, nosed over and plunged into the sea in a “spectacular” splash.

At the same time another plane attacked from Kitkun Bay’s starboard beam and passed just astern of the ship. The entire midship and after starboard batteries opened up on the aircraft and possibly killed all of the crew, since it failed to drop a torpedo. As the torpedo bomber cleared the stern, the port guns shot into it and the bomber splashed into the water about 300 yards off the port quarter. Another torpedo plane thrust at either Coral Sea or Gambier Bay, which appeared to bear the brunt of the assault, as they steamed astern of Kitkun Bay. A 5-inch round from Kitkun Bay hit it squarely and a ball of flame erupted from the assailant as it just cleared the bow of the other carrier and crashed into the Pacific.

Lt. William H. Johnson, USNR, and Ens. Krouse flew a pair of Wildcats (BuNos 16180 and 46959) that went down during the chaotic aerial maneuvering on the 18th. Destroyers rescued both men, Krouse after having survived his second fighter loss in as many days.

Throughout the day on 19 June 1944, TF 58 repelled Japanese air attacks and slaughtered their aircraft in what Navy pilots dubbed the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.” Kitkun Bay operated with her cohorts to the eastward of Saipan when American radar detected multiple Japanese strike groups about ten miles out and heading toward the fleet early that morning, and at 0624, Kitkun Bay launched a pair of Wildcats for CAP, joined a minute later by the first of five from Gambier Bay. The enemy closed the range rapidly and within five minutes a trio of dive bombers attacked the formation from an altitude of about 5,000 feet. The Japanese planes dropped two bombs that splashed close aboard Gambier Bay and then winged off, but a minute later two torpedo bombers approached the ships from the east. The vessels of the formation shot a heavy concentration of antiaircraft fire at the pair and they broke off and withdrew without making their runs.

The escort carriers continued flight operations throughout the busy day and that afternoon launched a bomb strike that included six Avengers from Kitkun Bay that attacked the Japanese ashore on Saipan. The usual late afternoon bogey alarms sent the ship’s company scrambling to their battle stations at 1618, but the vessels of the formation blazed away with every available gun and the enemy planes came about without attacking.

The following day, Kitkun Bay sent her Avengers aloft for early morning antisubmarine patrols. The ship then worked with Gambier Bay and their screening vessels in providing a triple defense of antiaircraft, antisurface, and antisubmarine cover for the transports of the Joint Expeditionary Force, TF 51, Vice Adm. Richmond K. Turner, as they operated about 60 miles to the east of Saipan. Ens. James C. Lucas, USNR, flew a TBM-1C (BuNo 17055) from the ship that crashed, but a destroyer rescued Lucas and his crew.

Kitkun Bay celebrated her 1,000th landing with cake on 21 June 1944. At noon, Laws slipped alongside Kitkun Bay as the two ships rolled in the swells and transferred a Japanese prisoner to the carrier. The destroyer had picked-up the 19-year-old Sumatran when she discovered him floating in a raft two days before. The man served with the Japanese and flew a patrol from Yap [Wa’ab] in the Caroline Islands to Rota in the Marianas, and unsuccessfully attacked Gambier Bay on the 17th. Kitkun Bay’s security detachment temporarily incarcerated the prisoner in the ship’s brig.

A torpedo passed beneath Benham’s stern while the ships of the formation covered Turner’s transports on the 22nd. Benham attacked the submarine and dropped five depth charges, but the destroyer lost contact and the enemy boat eluded destruction. The task unit joined TU 52.14.2, consisting of Idaho (BB-41), New Mexico (BB-40), Pennsylvania (BB-38), Honolulu (CL-48), St. Louis (CL-49), and their screen of destroyers, on 24 June. Two days later, Kitkun Bay sighted Saipan and a plane flew the prisoner to Aslito Airfield on the island. The ship launched daily ground support missions, and early on the 29th sounded general quarters when she detected unidentified planes on her radar, though they did not approach.

Kitkun Bay hurled her aircraft against enemy troops on both Saipan and Tinian, and later that day lookouts on a number of vessels sighted several torpedoes thrusting through the water toward the group, but the escorting destroyers proved unable to obtain good attack runs on the enemy submarine or submarines. Bogeys sent the crew to their battle stations again the following day, only to see the enemy wing off without attacking. Early July brought a brief respite at Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands as Kitkun Bay and her companions swung around on the 2nd of the month and made for the atoll.

“Schedule of support aircraft maintained today much appreciated by troops,” Rear Adm. Harold B. Sallada, Commander Support Aircraft, messaged Kitkun Bay as she came about. “Supporting aircraft executed close support expertly. Not only the troops like what you are doing but we do.”

“At Saipan we became a fighting ship because the crew, “Lt. Robert E. Thomlinson, USNR, who served on the staff of Rear Adm. Ralph A. Ofstie (see below), reflected, “which had been full of the usual Navy gripe up to that time, suddenly found itself…From that time on, the Kitkun Bay was in the thick of the fight and did her share…Of the ships I was on during the war, she was my favorite and always will be.”

Kitkun Bay took on stores, ammunition, and fuel while at Eniwetok (5–10 July 1944). The warship then turned her prow back to the fighting and, in company with Gambier Bay, Laws, and Morrison, set course for Saipan and arrived in the area on the 15th. Through the end of the month, planes flying from Kitkun Bay performed almost every type of potential carrier assignment against the Japanese forces defending Saipan and Tinian including CAP, hunting for submarines, bombing and strafing attacks, observing for artillery fire, and making smoke to assist minesweepers as they swept the channels for mines.

The ship lost three fighters during these battles. Lt. Cmdr. Richard L. Fowler went down in a Wildcat (BuNo 16346) he flew off the flight deck of the carrier on 15 July but survived. Two days later, it was the turn of Lt. Paul B. Garrison, USNR, in an FM-2 (BuNo 47330). Ships picked-up both men and subsequently returned them to the carrier. Lt. Robert C. White of VC-5 went down in a Wildcat (BuNo 55281) while flying a mission from Kitkun Bay on 18 July. At 1321, Morrison rescued White and at 1345 went alongside Kitkun Bay to transfer the pilot, before the destroyer resumed her screening duties.

Gambier Bay, Kitkun Bay, Cassin Young (DD-793), Callaghan (DD-792), Irwin (DD-794), and Porterfield (DD-682) formed a new task unit on 1 August 1944, and charted a course for an operating area east of Guam. The carriers launched planes that provided air cover over the soldiers and marines battling the Japanese for control of the island (2–4 August). At 1704 on the 3rd, an Avenger of VC-10 flying an antisubmarine patrol from Gambier Bay sighted a periscope and attacked with depth charges, causing oil and debris to rise to the surface. The enemy submarine escaped.

The ships then came about and anchored at Eniwetok (7–11 August). On the 8th, Rear Adm. Ofstie relieved Rear Adm. Sallada in command of CarDiv 26 and broke his flag in Kitkun Bay. Late on the afternoon of 11 August, Kitkun Bay stood out to sea for Espíritu Santo, where she completed voyage repairs, took on fuel, provisions, and ordnance, and sailors repainted much of the ship. Following that work, the vessels of the task unit got underway for a brief (24–26 August) sail to Purvis Bay in the Florida Islands [Nggela] of the Solomons. Kitkun Bay received orders to anchor at times in the harbor at Gavutu [Ghuvatu Harbour], which afforded the carrier a temporary base of operations while she girded herself for future operations by practicing attacks in support of amphibious landings in an area to the southwest of nearby Guadalcanal, and in New Georgia Sound (27 August–8 September).

Heading westward on 8 September 1944, Kitkun Bay and the ships of the task unit escorted an assault force of transports and dock landing ships for Operation Stalemate II—the landings of the 1st Marine Division on Peleliu and Angaur Islands in the Palaus. The convoy passed around the west end of Florida Island, between Santa Isabel and Malaita Islands, and proceeded at 12.5 knots. The carriers launched daily CAP and antisubmarine patrols to protect the marines during the passage. Kitkun Bay struck a heavy log at 0142 on the 13th and it lodged in her bow, reducing the ship’s speed by almost a knot. The log stayed jammed into the hull for nearly 45 minutes in spite of changes of course to dislodge it, but it finally broke free without significantly damaging the ship and she resumed her voyage at the convoy’s speed.

The Japanese had prepared their main line of resistance on Peleliu inland from the beaches to escape naval bombardment, and three days of preliminary carrier air attacks in combination with intense naval gunfire failed to suppress the tenacious defenders. The ship hurled her planes against the enemy each day of her deployment to the battle (15–25 September 1944) as they flew photographic reconnaissance flights, and bombing and strafing runs, along with the usual CAP and antisubmarine barrier patrols to protect the ships operating offshore.

Lt. Johnson flew a mission from Kitkun Bay on the 20th that included dropping a message to attack transport Fremont (APA-44). He then joined a strike against the Japanese ashore but one of the aircraft released a bomb that touched off an enemy ammunition dump. The explosion damaged his Wildcat and forced him to land on the war-torn island. The ship later sent a plane that landed on Peleliu Airfield, and picked the pilot up and returned him to the carrier. The following day on 21 September, Japanese antiaircraft fire damaged two of the Avengers flying from the ship over Babelthuap [Babeldaob] Island. Both torpedo bombers landed on the airfield on Peleliu, the first with a couple of wounded crewmen. The second plane managed to lift off again and fly back to the ship.

After recovering aircraft that afternoon, the carriers and their escorts steamed to positions astern of some of the transports and dock landing ships, and the combined group then came about for Ulithi Atoll in the Carolines. The Army’s 81st Infantry Division later reinforced the marines and the final Japanese on Peleliu only surrendered on 1 February 1945. Stopping briefly at Ulithi, the escort carriers and their escorts stood down the channel on the afternoon of 25 September 1944, for the three-day trip to New Guinea, and then continued on to Seeadler Harbor on Manus in the Admiralty Islands. Kitkun Bay loaded fuel, ammunition, and stores while at the anchorage (1–11 October), and prepared to take part in the invasion of Leyte in the Philippines.

Screened by four destroyers, Gambier Bay and Kitkun Bay turned their prows seaward on 12 October 1944, and on the following day rendezvoused with a group of cruisers, destroyers, and landing craft. The force steamed toward Philippine waters in the vicinity of Mindanao, where the carriers and their screen detached on the 19th to join other carriers, and the invasion vessels continued on to Leyte Gulf.

Adm. William F. Halsey Jr., Commander, Third Fleet, led nine fleet and eight light carriers in those troubled waters. Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid, Commander, Seventh Fleet, led a force that included TG 77.4, Rear Adm. Thomas L. Sprague—consisting of 18 escort carriers organized in Task Units (TUs) 77.4.1, 77.4.2, and 77.4.3, and known by their voice radio calls as Taffys 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Chenango (CVE-28), Petrof Bay (CVE-80), Saginaw Bay (CVE-82), Sangamon (CVE-26), Santee (CVE-29), and Suwanee (CVE-27) and their screens formed Taffy 1, Rear Adm. Thomas Sprague, and fought off northern Mindanao. Chenango and Saginaw Bay swung around on the 24th to carry planes to Morotai in the Netherlands East Indies [Indonesia] for repairs and overhaul. Kadashan Bay (CVE-76), Manila Bay (CVE-61), Marcus Island (CVE-77), Natoma Bay (CVE-62), Ommaney Bay (CVE-79), and Savo Island (CVE-78) of Taffy 2, Rear Adm. Felix B. Stump, operated off the entrance to Leyte Gulf.

Two CarDivs formed Taffy 3, Rear Adm. Clifton A. F. Sprague, off Samar. Fanshaw Bay (CVE-70), Kalinin Bay (CVE-68), St. Lo (CVE-63), and White Plains (CVE-66) formed CarDiv 25, Rear Adm. Clifton Sprague, while Gambier Bay and Kitkun Bay comprised CarDiv 26, Rear Adm. Ofstie. Heermann (DD-523), Hoel (DD-533), and Johnston (DD-557), together with escort ships Dennis (DE-405), John C. Butler (DE-339), Raymond (DE-341), and Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413), screened Taffy 3.

The Army’s 6th Ranger Battalion landed on Dinagat and Suluan Islands at the entrance to Leyte Gulf to destroy Japanese installations capable of providing early warning of a U.S. attack, on 17 October 1944. The garrison on Suluan transmitted an alert that prompted Adm. Toyoda Soemu, the Japanese Commander in Chief of the Combined Fleet to order Shō-Gō 1—an operation to defend the Philippines. The raid thus helped to bring about the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

While the enemy gathered his naval and air forces, the Allies landed on Leyte. Kitkun Bay operated from a position east of Samar and launched multiple air strikes to support the troops as they fought their way ashore and then inland (20–25 October). Planes bombed and strafed the Japanese troops and their positions, flew reconnaissance missions, and maintained CAP over the ship and her consorts. In addition, the carrier provided fighters to protect transports and the invasion beaches. Lt. (j.g.) Donald W. Hyde, USNR, of VC-5 flew a Wildcat (BuNo 16274) from the ship that went down on the 20th, but the pilot survived.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf, a succession of distinct fleet engagements, began on 22 October 1944, when Shō-Gō 1 attempted to disrupt the U.S. landings in Leyte Gulf. Japanese fuel shortages compelled them to disperse their fleet into the Northern (decoy), Central, and Southern Forces and converge separately on Leyte Gulf. Attrition had reduced the Northern Force’s 1st Mobile Force, their principal naval aviation command and led by Vice Adm. Ozawa Jisaburō, to carrier Zuikaku and light carriers Chitose, Chiyōda, and Zuihō. Submarine Darter (SS-227) detected a group of Japanese warships northwest of Borneo on the 22nd and into the following day shadowed them. Bream (SS-243) meanwhile torpedoed heavy cruiser Aoba off Manila Bay, and Darter and Dace (SS-247) unflinchingly attacked what turned out to be the Japanese Center Force, Vice Adm. Kurita Takeo in command. Dace sank heavy cruiser Maya, and Darter sank heavy cruiser Atago and damaged her sistership Takao, which came about for at Brunei.

The planes of TG 38.2, TG 38.3, and TG 38.4 attacked Kurita as his ships crossed the Sibuyan Sea. Enterprise, Intrepid (CV-11), Franklin (CV-13), and Cabot launched strikes that sank battleship Musashi south of Luzon. Aircraft from the three task groups also damaged battleships Yamato and Nagato, heavy cruiser Tone, and destroyers Fujinami, Kiyoshimo, and Uranami. Planes furthermore attacked the Southern Force as it proceeded through the Sulu Sea, and sank destroyer Wakaba and damaged battleships Fusō and Yamashiro. Ozawa in the meanwhile decoyed Halsey’s Third Fleet northward, and aircraft subsequently sank all four Japanese carriers, Chitose with the assistance of cruiser gunfire, off Cape Engaño. Halsey’s rapid thrust, however, carried his ships beyond range to protect the escort carriers of Taffy 3.

Occasional rain squalls swept through the area as the sun dawned on Wednesday, 25 October 1944. The visibility gradually opened to approximately 40,000 yards with a low overcast, and the wind was from the north-northwest. Kitkun Bay and the other ships of Taffy 3 greeted the day preparing to launch strikes to support the troops fighting ashore. The carriers thus armed their planes with light bombs and rockets to attack Japanese soldiers and positions, or depth charges for those intended to fly antisubmarine patrols, armament not well suited for attacking ships.

Unbeknownst to Kitkun Bay and her consorts, however, the surviving ships of the Japanese Center Force, which included battleships Yamato, Haruna, Kongō, and Nagato, heavy cruisers Chikuma, Chōkai, Haguro, Kumano, Suzuya, and Tone, light cruisers Noshiro and Yahagi, and 11 destroyers, made a night passage through San Bernardino Strait into the Philippine Sea.

Ens. William C. Brooks, Jr., USNR, of Pasadena, Calif., flew a TBM-1C of VC-65 from St. Lo and sighted the pagoda masts of some of the Japanese ships at 0637 on 25 October 1944. Brooks initially surmised that they might be Allied reinforcements but followed established procedure and radioed a sighting report. His superiors demanded confirmation so he closed the range and positively identified some of the enemy vessels. Undaunted by the overwhelming enemy firepower, Brooks and his Avenger crew pressed home two attacks against a Japanese heavy cruiser, dropping depth charges that bounced off the ship, and then joined a pair of Avengers that dived on one of the battleships, feats of extraordinary heroism for which the pilot later received the Navy Cross.

Lookouts on board the ships of Taffy 3 could see bursts of Japanese antiaircraft fire on the northern horizon as the enemy vessels fired at the Avengers, and within minutes, ships began to detect the approaching Japanese vessels on their radar, and to intercept enemy message traffic. The Japanese surprised the Americans and caught Taffy 3 unprepared to face such a powerful onslaught, and the battle almost immediately became a precipitate flight in the face of the overwhelming enemy force. Sprague ordered his ships to come about to 090° at 0650, and flee to the eastward, hoping that a rain squall would mask their escape. Taffy 3 urgently called for help, the carriers scrambled to launch their planes, and the escorts steamed to what quickly became the rear of the formation to lay protective smoke screens.

Kitkun Bay’s crew raced to man their battle stations and the ship sounded flight quarters as the enemy opened fire. She rang up flank speed for 18½ knots, and swung around to 070° to head partly into the wind for launching planes and yet to keep away as much as possible from the more heavily armed Japanese ships. The carrier launched eight Wildcats that were already warming up for the day’s action (0656–0703). At 0702 ships began making smoke, and the heavy pall of smoke and the general murkiness of the weather often prevented men from seeing the entire picture. Beginning at 0710, Kitkun Bay launched six Avengers to engage the enemy. The ship changed course to 110°, but briefly turned back into the wind to launch a ninth fighter at 0711.

A heavy rain squall blotted the action from view for a few minutes that morning and Kitkun Bay continued to zig-zag. The formation turned to 190° but enemy shells hurtled toward the American ships and splashed near White Plains and off Kitkun Bay’s port beam. In the forefront of the circular formation, Kitkun Bay escaped any direct hits as the shells splashed ever closer astern, but several salvoes bracketed the carrier and the near misses held little hope that her good fortune could continue.

Sprague ordered the escorts to make a torpedo run at the Japanese ships at 0740, but by this time, the enemy vessels reached a point bearing 355° from Kitkun Bay at 25,000 yards. Men watched with trepidation as the flashes of the enemy guns announced more salvoes that tore through the air and fell only about 1,500 yards astern of the ship. Kitkun Bay began to jettison her gasoline bombs and smoke tanks at 0755, and Sprague directed all of the carriers to make as much smoke as possible. Maintainers meanwhile scrambled to load the remaining Avengers in the hangar deck with torpedoes, while the ship swung to 195° at 0756 to permit the other vessels to get behind the smoke screen. Three destroyers appeared off the port bow at a range of approximately ten miles and in the confusion, lookouts initially identified them as Japanese, only to discover some of the U.S. ships fighting faithfully to protect their vulnerable charges.

“The enemy is now within range,” the captain instructed Lt. Edward L. Kuhn, USNR, Kitkun Bay’s gunnery officer, “Mr. Kuhn, you may fire the 5-inch at will.” His gunners opened fire and altogether shot 120 of the 180 rounds stored on board, a telling tribute to their frantic defense of the ship, with Kuhn’s “cool courage under fire” contributing to the gun crew’s efficiency (and resulting in his later receiving a Bronze Star). One of their 5-inch shells plunged into a Japanese ship, tentatively identified as a cruiser, at 0759 on 25 October 1944, and started a fire forward. Kitkun Bay swung over five degrees to the westward to keep away from the enemy ships, two of which in sight, Chikuma and Tone, changed course to south-southeast to pursue the carriers. Kitkun Bay changed course to 240° at 0803, and launched a trio of Wildcats.

The crew’s hope for survival dropped when an enemy submarine’s periscope was reported off the port bow. Japanese submarines aggressively penetrated Allied defensive screens and torpedoed carriers more than once during the war, and the enemy boat, if such she was, maneuvered in a perfect position to pick of a carrier as one passed on its enforced course. Kitkun Bay swung over to 205° to present as small a target as possible and enable the escorts to attack the submarine. One of the Avengers claimed to sight the periscope and dived on it, the pilot later expressing his belief that his depth charges sank the submarine. A puff of reddish smoke and the green dye marker that the plane dropped revealed the only evidence of the submarine, and Kitkun Bay passed almost over the spot where the lookout first sighted the periscope. The elusive submarine, if one indeed ever prowled the area, vanished without a trace.

Japanese shells slammed into Gambier Bay and set the ship ablaze, and some of the enemy vessels, evidently believing they had finished her off, shifted their fire to Kitkun Bay as she briefly emerged from the smoke. A salvo splashed scarcely 1,000 yards astern at 0828, and the captain furiously zig-zagged the ship and attempted to slip back within the cover of the smokescreen to escape the enemy gunfire as they dropped the range. Another salvo erupted in the water 1,000 yards off the port beam at 0830, and a minute later a third salvo splashed 700 yards astern. The next salvo tore into the sea 500 yards off the starboard beam as the Japanese found the range.

Kitkun Bay experienced a ray of hope at 0834 when she received news that the planes of the strike group had refueled ashore and were returning to protect their ship. The other carriers sent their aircraft aloft and a flight of 24 planes passed over Kitkun Bay a few minutes later and dived on the enemy cruisers, which opened fire at them. Kitkun Bay’s 5-inch gun continued the unequal contest and hurled shot after shot at the enemy cruisers, but they, in turn, fired another salvo that splashed off the port beam. The ship’s radar picked up unidentified aircraft ten miles to the northwest at 0858, and worried watchstanders anticipated adding Japanese planes to the threat facing them.

White Plains also fired her single 5-inch gun at one of the enemy heavy cruisers, most likely Chokai. Samuel B. Roberts fought Chokai as well, and at 0859 a secondary explosion erupted from the enemy vessel, possibly as some of her torpedoes cooked off. The blast knocked out her engines and rudder, and she sheered out of line. The other enemy cruisers continued firing and a salvo splashed barely 200 yards astern of Kitkun Bay. Haguro, which took Chikuma’s place in position, and Tone appeared to outdistance the rest of the Japanese ships and drew up toward Kitkun Bay. The enemy ships dropped the range until they closed on Kitkun Bay’s port beam at 12,000 yards, and their next salvo straddled the carrier as their shells splashed on both sides.

The embattled carrier’s 5-inch had fired almost all of the ammunition at hand, and the captain ordered the gunners to cease fire and conserve the remaining rounds because he expected that the enemy destroyers would attack. A Japanese salvo splashed a mere 20 yards astern and the alarmed gun crew believed that the following salvo would slice into the ship. Capt. Whitney thus swung the warship between 200° and 270° in an effort to forestall the apparently inevitable. Cmdr. Fowler also attempted to save Kitkun Bay and led four Avengers flying from the ship that assailed Chokai at 0905. One of the planes dropped a 500-pound bomb that tore into the Japanese vessel’s stern, and smoke emerged from the cruiser and she slowed.

Just as the situation looked very bleak for Kitkun Bay and the other ships, the enemy suddenly broke off the engagement at 0925 and retired. As a relieved Capt. Whitney watched them continue to do so at 0931, he ordered the vessel to slow down to 15 knots and to cease making smoke. Four ships, valiantly fighting to the end, went down: Gambier Bay, Hoel, Johnston, and Samuel B. Roberts. In addition, Japanese gunfire damaged Kalinin Bay, Dennis, and Heermann, and straddled Kitkun Bay, St. Lo, and White Plains but scored no direct hits.

During the course of the next hour, Fanshaw Bay, Kitkun Bay, St. Lo, White Plains, Dennis, Heermann, John C. Butler, and Raymond formed disposition Charlie. The carriers turned into the wind to launch and recover planes, and Kitkun Bay controlled 14 fighters and six torpedo bombers in the air at 0950.

Kurita ordered Fujinami to escort Chokai at 1006, and as more aircraft attacked the pair, they shot down an Avenger. Kitkun Bay began launching five Avengers, four armed with torpedoes and the fifth with bombs, at 1013. At 1035, these five planes joined a sixth flying from St. Lo and attacked Yamato, the largest and most heavily armed battleship in the Japanese armada. The aircraft dived through intense antiaircraft fire and assailed the behemoth but failed to score any confirmed hits.

The final phase of the Battle off Samar included retaliatory air strikes by both sides. As many as eight enemy aircraft, at least five of them Mitsubishi A6M2 Navy Type 0 carrier fighter Model 21s of the Tokkōtai suicide squadron Shikishima, suddenly appeared over the formation at 1049, and singled out the carriers for their fury.

“A few minutes later,” Lt. Thomlinson recalled, “another kamikaze came in and landed upon our flight deck, killing and injuring some of our gunners. The sky was full of planes, [Japanese] and ours. Ours were from the 18 escort carriers which were ranged within 75 miles of our position.”

The Zeke that Thomlinson described turned and dived on Kitkun Bay from the starboard side. Fanshaw Bay added her guns to those of her fellow carrier, but the kamikaze absorbed the heavy concentration of fire, cleared Kitkun Bay’s flight deck, and crashed into the port walkway netting. The shock carried away about 15 feet of the netting and its braces, the port aerial, and the life raft suspended from the netting frame. The 550-pound bomb exploded on impact, bursting evidently on a level with the walkway, and showering fragments into the nearby gun sponsons and the ship’s side from the forecastle to No. 6 sponson. The kamikaze assault punctured more than 100 holes in the bulkheads, doors, and gasoline lines. The broken gasoline lines permitted the fuel to flow into a gun sponson but a fire did not start and men washed the gasoline overboard. The attack killed AMM3c Graham C. Hatfield, seriously wounded four more, and slightly wounded another 12. In addition, the kamikaze destroyed two Avengers (BuNos 46201 and 46202) on board the ship.

One enemy plane crashed into the sea and another flew directly into the flight deck of St. Lo. Dennis “took a position as close as we dared on account of the violent explosions occurring and commenced picking up survivors,” who were by then abandoning ship from St. Lo. At 1108, another enemy plane crashed into White Plains. Dennis continued picking up survivors for the next several hours, eventually bringing 425 of them on board from St. Lo, six from White Plains, and three from Petrof Bay. Finally, at 1432, Dennis “secured from general quarters.” Two kamikazes also damaged Kalinin Bay.

Lookouts sighted 15 more Japanese planes at 1100, and Kitkun Bay hurriedly launched two Wildcats to join the other fighters of the CAP. The enemy aircraft attacked the ship by approaching her from nearly dead astern. A Yokosuka D4Y Type 2 carrier bomber Suisei seemingly intent on destroying the radar mast and island flew toward the ship, but gunfire set the Judy aflame and the kamikaze passed over the bridge and exploded when opposite the forward end of the flight deck. Parts of the plane, including the starboard horizontal stabilizer from its tail, and the pilot, fell onto the flight deck and the forecastle. The bomb, estimated to be a 1,100-pound weapon, dropped into the water near the bow and exploded, inflicting only inconsequential damage to the light metal parts of the ship and throwing a heavy column of water into the air. The carrier’s starboard side passed through this column of water, drenching hands on the rope bridge and forward gun sponsons. None of the other aircraft attacked Kitkun Bay and the survivors disappeared a few minutes later as they returned to their field.

Five Avengers from Kitkun Bay meanwhile at 1105 attacked Chikuma. The Japanese heavy cruiser had already fired most of her antiaircraft ammunition against the U.S. planes that attacked her while crossing the Sibuyan Sea—some of her guns expended all of their live rounds and the gun crews resorted to shooting training rounds. Two torpedoes sliced into the cruiser’s port side amidships and water poured into her engine room, causing the ship to lose power. Chikuma drifted to a stop and began listing to port. Nowaki swung around at 1110 to render assistance to her stricken cohort Chikuma.

The men of Kitkun Bay steeled themselves for another aerial assault when the radar identified a flight of planes, but breathed a sigh of relief when the intruders turned out to be a strike group from Hornet (CV-12) and Wasp (CV-18) en route to attack the retreating the Japanese, at that point about 38 miles to the northward on a heading for San Bernardino Strait. Some of the aircraft from the ship joined the strike.

The enemy franticly battled the damage to Chikuma and attempted to save their ship, but Lt. Allen W. Smith Jr., the commanding officer of VC-75, led a trio of that squadron’s TBM-1Cs from Ommaney Bay that dropped three more torpedoes that ripped into her port side at 1415. Within 15 minutes, the battered warship rolled over and sank by the stern. Nowaki pulled about 120 survivors from the water.

In the Battle off Samar and the Japanese retirement, the Americans damaged Yamato, Kongō, Chikuma, Chōkai, Haguro, Kumano, Suzuya, and Tone. Chikuma Chōkai, and Suzuya suffered repeated explosions and fires and destroyers Nowaki, Fujinami, and Okinami, respectively, scuttled the cruisers with torpedoes—though Nowaki may have reached the area after U.S. aircraft delivered the coup de grâce to Chikuma. About 60 planes from TGs 38.2 and 38.4 tore into the retiring Japanese and sank Noshiro on the 26th. That day U.S. cruisers also crippled Nowaki with gunfire, and Owen (DD-536) sank her about 65 miles south-southeast of Legaspi, Luzon. The casualties the Japanese surface fleet sustained and its virtual withdrawal to anchorages because of a lack of fuel finished it as an effective fighting force.

Hale (DD-642), Picking (DD-685), and Coolbaugh (DE-217) joined the formation that evening. Kitkun Bay secured from general quarters at 1840 on 25 October 1944, having been at battle stations for 11 hours and 47 minutes. The weary crew enjoyed little time for a respite when, at 2002, an unidentified surface contact and believed to be a surfaced submarine, trailed the formation for some time at a range of 19,400 yards. Coolbaugh dropped several depth charges on the contact, though without noticeable results. Kitkun Bay’s busy radar plot detected bogeys seven miles to the north at 2135. For an hour and 34 minutes the planes circled the formation suspiciously at a distance of two to five miles but never attacked, and then just as mysteriously winged off into the night.

Kitkun Bay’s losses for the day included two torpedo planes and both of their pilots and two of their crewmen: Ens. James C. Lucas and ARM3c William B. Latimer (BuNo 46343), and Ens. Allen A. Pollard and AOM2 Frank L. Orcutt. One of the Avengers fell into the sea about five miles off Kitkun Bay’s port bow—though identifying which proved difficult in the heat of battle. The Japanese furthermore shot down four Wildcats: Lt. (j.g.) Robert T. Sell (BuNo 47393), Ens. Paul Hopfner (BuNo 16386), Ens. Geofrey B. King (BuNo 47247), and Ens Murphy (BuNo 47304). The four fighter pilots flew with VC-3 but in the confusion of the fighting landed on board Kitkun Bay, which, in those tumultuous moments, became the closest carrier in sight and not aflame, and then returned to the fray. All four men survived the harrowing experience.

The following day, Kitkun Bay worked with the other vessels of Taffy 3 as they patrolled to the eastward of Leyte until they received orders to return to Seeadler for replenishment and repairs. Fanshaw Bay, Kalinin Bay, Kitkun Bay, White Plains, Dennis, Hale, Halligan (DD-584), Haraden (DD-585), Hutchins (DD-476), Raymond, and Twiggs (DD-591) came about and shaped a course to the eastward, though Hale presently detached from the convoy. Planes from Kitkun Bay flew patrols for the formation all the way to Manus via Mios Woendi in the Padaido Islands of Netherlands New Guinea [Indonesia]. While en route at 1400 on the 27th, Halligan made an underwater sound contact and dropped 11 depth charges with inconclusive results. The damaged carriers required escorts and so she rejoined the formation without regaining contact.

The ships reached Woendi harbor on 29 October 1944, refueled, and set course for Manus the next morning, and on the afternoon of 1 November slipped into Seeadler Harbor. The port authorities welcomed the returning veterans by sending out a band in a re-arming barge. Fanshaw Bay, Kalinin Bay, Kitkun Bay, White Plains, Dennis, Hutchins, and Raymond cleared the harbor on the 7th and set a course for Hawaiian waters. The carriers flew off their flyable planes to Ford Island on the morning of the 18th, and that afternoon entered Pearl Harbor. While the ship lay there at 1100 the following morning, VC-5 went ashore for a much needed period of rest and training. The ship’s company gave the aviators a “big send-off and regretted parting with such a fine squadron.” That same afternoon the warship began a ten-day (19–29 November) availability in dry dock at the navy yard.

Kitkun Bay wrapped-up her work on 29 November 1944, and that afternoon and evening VC-91 moved on board as her new squadron. Established in February 1944, VC-91 also flew FM-2 Wildcats, as well as TBM-3 Avengers. The ship then (30 November–3 December) trained in the waters south of Oahu, enabling her new pilots to attain their carrier qualifications. A trio of escorts screened the ship as she turned her prow back to the fighting on 5 December. The following day, Ens. Claggett H. Hawkins of VC-91, embarked on board the ship, fatally crashed in a TBM-3 Avenger (BuNo 22880). John C. Butler rescued one survivor, ARM3c T.J. Szpont.

On the 11th, Edmonds (DE-406), one of the carrier’s escorts, detected an apparent submarine and made a number of depth charges attacks without noticeable effect. That afternoon, all doubts about the accuracy of her discovery vanished when lookouts sighted two torpedo wakes rushing toward Edmonds, one of which passed beneath her as it evidently ran too deep, and the other swished by just ahead of her. All three escorts fell back and searched for their prey while Kitkun Bay proceeded on a westerly course using evasive tactics. After several hours of fruitless search, the escorts rejoined the ship and they all dropped anchor in Seeadler Harbor on 17 December 1944. Rear Adm. Ofstie returned to Kitkun Bay and broke his flag in command of CarDiv 26 as the ship took on stores, ammunition, fuel, and replacement planes for her next battle.

In spite of almost continuous harsh weather during January 1945, the Allies invaded Lingayen Gulf on western Luzon in the Philippines. Kitkun Bay, Shamrock Bay (CVE-84), and their escorts cleared Seeadler Harbor at 0941 on New Year’s Eve 1944, and set a course to rendezvous with the rest of the invasion fleet. They joined two transport groups at 1600 that afternoon, and the combined forces continued on their voyage. Lt. Cmdr. Bernard D. Mack, VC-91’s commanding officer, wrecked in a Wildcat (BuNo 73569) on 4 January 1945. Mack survived the crash but in a pre-dawn take-off from Kitkun Bay the next morning, disappeared in another Wildcat (BuNo 73551). A thorough search of the area failed to locate either Mack or his plane.

The Japanese reacted vigorously to the landings and their planes attacked the invasion forces during the transit from Leyte Gulf. TF 38, Vice Adm. John S. McCain in command, including seven heavy and four light carriers, a night group of one heavy and one light carrier, and a replenishment group with one hunter-killer and seven escort carriers, nonetheless concentrated on destroying enemy air power and air installations. On 3 January 1945 carrier planes bombed Japanese airfields and ships at Formosa [Taiwan]. Three days later Ofstie’s Lingayen Protective Group, TF 77.4.3, part of the vast assemblage and consisting of Kitkun Bay, Shamrock Bay, John C. Butler, and O’Flaherty (DE-340), entered Surigao Strait. An air alert sent men scrambling to man their battle stations but the enemy failed to attack.

The following morning on 7 January 1945, however, a kamikaze aimed his death dive at Kadashan Bay, which steamed about 50 miles to the north of Kitkun Bay. Despite repeated hits the enemy plane plunged into the carrier amidships directly below the bridge. After an hour and a half of feverish damage control effort, the crew checked the fires and flooding. The battered ship returned to Leyte for temporary repairs on 12 January, and on 13 February set out for a complete overhaul at San Francisco, Calif.

The enemy attack served as a heads-up for Kitkun Bay, and she received a report of more unidentified aircraft closing from the north at 15 miles. Lookouts sighted antiaircraft bursts on the horizon scarcely ten miles away as Japanese planes attacked other vessels of the invasion forces. The ship steamed at general quarters several minutes later at 0910, when a lone enemy bomber appeared close to the water and closing the formation just four miles off the starboard quarter. Multiple escorts opened fire and the enemy pilot maneuvered erratically to avoid the gunfire and escaped. The Wildcats of the warship’s CAP claimed to splash three other intruders and by 1115 the radar seemed clear of enemy aircraft and the ship secured from battle stations.

Vice Adm. Theodore S. Wilkinson, Commander, TF 79, sent a “Flash Red” at 1806 that evening as additional bogeys approached from a range of 20 miles. The ship’s fighters pounced on the attackers and claimed to splash four to six planes. The enemy determinedly pressed home their attack nevertheless, and cruisers and destroyers closed Kitkun Bay and blasted away at the attackers to protect her. The carriers headed into the wind to conduct flight operations in order to recover aircraft from Kadashan Bay, and two of the latter’s FM-2s from VC-20 landed on board Kitkun Bay. Lt. (j.g.) William F. Jordan, USNR, of VC-91 went down in a Wildcat (BuNo 73617) but a destroyer rescued Jordan.

Lookouts sighted enemy planes circling about three miles off the ship’s port bow at about 6,000 feet at 1848 on 7 January 1945, near 16°N, 119°10'E. The rumble of antiaircraft fire from the cruisers and destroyers increased in crescendo; however, in a few minutes two Japanese Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa Army Type 1 fighter planes detached from their formation and flew toward the carriers. One of the Oscars turned at 1857 and dived on Kitkun Bay from a relative bearing of 330°.

All available guns including Montpelier (CL-57) and Phoenix (CL-46) opened up on the Oscar and shot off parts of the plane, but the pilot continued his dive through what the ship’s historian described as “murderous fire,” levelled off close to the water at 3,000 yards, and crashed the suicide plane through the port side at the waterline amidships. An explosion and large fire flared up simultaneously with a hit by a 5-inch round from one of the other ships, which burst close to the carrier’s bow below a gun sponson, killing and wounding several men—the attack killed 16 men altogether and wounded another 37. The Oscar tore a hole in the ship’s side approximately 20 feet long and nine feet high between frames 113 and 121, extending three feet below the waterline.

Kitkun Bay lost power and began listing to port rapidly as her after engine room, machine shop, and gyro spaces flooded. The list increased to 13° with the trim down by the stern four feet at 1904. Maintainers shifted planes to the starboard side of the flight deck to help correct the list. Firefighters valiantly battled the blaze and extinguished the flames by 1910, but the flooding continued as seawater poured into the ship in spite of the efforts of the engineers and repair party to contain the damage. Rear Adm. Ofstie prudently ordered all secret and confidential publications destroyed to prevent them from falling into enemy hands. The Medical Department tended to the wounded, and then the captain passed the orders to transfer all “unnecessary” crewmen off the ship; wounded first. Destroyers took off 724 men, leaving less than 200 on board—the rescue party supplemented by volunteers. “We stayed upon the flight deck,” Lt. Thomlinson reflected, “ready to scramble into the sea, except when we had urgent business below decks. At 19 degrees list there’s no comfort on a carrier.”

Despite the risk of a fire touching off ammunition and fuel on board Kitkun Bay, fleet ocean tug Chowanac (ATF-100) closed the carrier and secured a tow line to her at 2042, and they proceeded toward Santiago Island in the vicinity of Lingayen Gulf. The engineers got steam up in the forward engine room and the damage control teams reduced the list to four degrees. Hopewell (DD-681) and Taylor (DD-468) left the formation to guide and escort Shamrock Bay (CVE-84), which operated a distance away, back into the group, and the carrier joined them during the mid watch. Ofstie then transferred his flag to Shamrock Bay.

Unidentified aircraft were reported nearby at 1430 on 9 January 1945, and the gun crews resignedly manned their weapons, though no attack developed. VC-91 counted 15 FM-2s, one FM-2P, a photographic variant, ten TBM-3s, and a single TBM-3P on board Kitkun Bay. The kamikaze claimed at least two Wildcats (BuNos 73589 and 74027) parked on board the ship. The situation nonetheless looked more hopeful as the morning progressed. The forward engine room had a head of steam and at 0815 eight fighters appeared overhead and protectively flew CAP over the ships. As the vessels approached Lingayen Gulf, crewmen sighted gunfire from both sides as the fighting continued ashore. Kitkun Bay gradually restored power and communications, and the tug cast off at 1030 and the carrier proceeded under her own steam, with speed limited to eight knots because of salt water steaming. Kitkun Bay lowered her colors to half mast at 1130 while the ship’s company committed their fallen shipmates to the deep.

Kitkun Bay proceeded on a westerly course to rendezvous with TG 77.4, but at 1822 received a report of enemy aircraft closing on the formation from the east. The warship sounded general quarters, and, although she could only make ten knots, a brisk breeze from the north enabled her to head into the wind and launch five Wildcats. The Japanese planes swung around and retired to the south without pressing an attack. The wind dropped to barely 15 knots and it was nearly dark by 1907 when the ship recovered her last fighters.

The ship operated in the vicinity of the task group throughout the 10th, a day punctuated by two air alerts, though the enemy did not attack. Increasingly heavy seas that evening made the battered carrier’s seaworthiness doubtful and maneuvering difficult. Capt. Albert Handly, the commanding officer, requested permission to join the first slow convoy to Leyte that passed in the area, and at 2200 Kitkun Bay received a message to join some tank landing ships of TU 79.14.3 and make for that island.

Kitkun Bay held the course and station by using the magnetic compass while she limped nearly 500 miles to Leyte Gulf during the next several days. On the 11th, Lt. (j.g.) James A. Jones, USNR, of VC-91 crashed in a Wildcat (BuNo 73623) flying from the ship but a plane guard destroyer rescued him.

On the 14th, the ship launched her own CAP, and later sent the fighters on to Tacloban Airfield on Leyte. Sighting Leyte that afternoon, Kitkun Bay entered Surigao Strait at 2336, and the following morning anchored in Leyte Gulf. Work on the ship progressed despite an enemy air raid on the night of the 18th. Smoke screens mostly obscured the Allied ships anchored in the roadstead, so the Japanese planes bombed some of the searchlights positioned on the beaches that they could spot.

Additional air alerts sent the crew to their battle stations more than once, but they placed a patch over the hole in the side and pumped the water out of the flooded compartments. Men discovered a Japanese 550-pound armor-piercing bomb wedged into the No. 3 boiler on the 20th. The deadly device had torn through Kitkun Bay and stopped there without exploding, but ordnance disposal sailors from Leyte boarded the ship and cut through the boiler to remove the bomb—while all hands stayed clear of the area. The bomb experts discovered a second unexploded 550-pounder in the previously flooded machine shop, and de-armed and jettisoned over the side both bombs, the first one at 2306 and the second at 1510 the following day.

“Experiment with converging or diverging boresight patterns on AA [antiaircraft] weapons,” Capt. Handly subsequently recommended to the fleet. “Make similar research with range setting and deflection devices. Try the elimination of all tracer and all 5-inch except Mark 32 or similar marks to deny pilot the knowledge of where the AA is and relieve gunners of the confusion of many bursts which tend to hide the plane, particularly at twilight. Tracers did not appear to assist our own gunners, and many guns apparently fired at 5-inch bursts.”

The Navy consistently evaluated the results of these battles and evaluators noted that the optimum pattern of antiaircraft guns and their systems varied greatly with the control, weapon, ammunition—and the action of the target. The fleet made tracerless 20-millimeter and 40-millimeter rounds available, and VT (proximity) fuzes did not have tracers. “If the control is adequate,” investigators responded, “the suggestion has considerable merit, although there is an undeniable psychological effect of tracers, both on the gunner and the attacking pilot.”

Handly’s dearly bought experience inspired him to make a number of other suggestions: “Test the value of a very tight screen, possibly with escort vessels closing to 200 yards upon Red alerts, to concentrate firepower, bolster morale, reduce deflection and reduce the masking of fire when low attacks fly between ships.....Place OBB’s [old battleships] in the center of CVE formations.”

“The best attempt to train was a number of simulated surprise attacks conducted by our embarked planes which afforded our gunners, lookouts and CIC [Combat Information Center] personnel an opportunity to improve their alertness making dry runs. These drills were effective, but did not enable us to stop the last attack...It is suggested that immediate research be pursued along the following lines by appropriate activities:

Develop a target for realistic gunnery exercises. This could be a water fillable bomb with a target sleeve attached, and containing a radio controlled device to explode the bomb harmlessly before it could strike the firing ship after being launched by a dive bomber. Radio-controlled gliders or drones, similarly equipped, would be still better.”

In addition, the captain expressed his concern about how close Japanese aircraft approached ships before the latter opened fire, in part because of the gunners’ fears of hitting their own returning planes. Handly thus proposed what, at first glance, seems a harsh yet practical solution:

“Enforce with a shoot - regardless policy, a doctrine prohibiting friendly pilots from making any but the prescribed approach to a formation of ships. Time cannot be wasted on positive identification.” The captain’s recommendation seemed merited in light of the horrific casualties the kamikazes caused.

Kitkun Bay stood out for home on 24 January 1945, her temporary repairs completed and 95 percent of the flooded compartments pumped out. A kamikaze had crashed Salamaua (CVE-96) on the 13th, and the damaged carrier and a screen accompanied Kitkun Bay, which sailed in tactical command of the group. The ships dropped anchor in Seeadler Harbor on 30 January, and the following day her men continued work on repairing their vessel. VC-91 detached on 4 February with orders to embark on board Savo Island, and Kitkun Bay’s historian observed that “with them went the gratitude and best wishes of the ship’s company.”

The ship loaded some aviation gasoline and ordnance, and the convoy resumed their voyage and steamed uneventfully to Pearl Harbor (5–17 February), where Kitkun Bay moored to Ford Island. The warship discharged her remaining aviation gasoline and considerable ammunition, and then turned further eastward and sailed to Naval Dry Docks, an activity on Terminal Island near San Pedro, Calif. (20–28 February). Kitkun Bay granted leave to the ship’s company in two periods of 20 days each. The welcome news marked the first leave for most of the crew following an extended tour of combat duty.

While the ship completed repairs on 26 February 1945, VC-7 received orders to report to her no later than 10 April. The squadron increased its tempo of training at Naval Air Auxiliary Station (NAAS) Monterey, Calif., but on the following day also participated in simulated close support attacks on the Army’s nearby Camp Hunter Liggett. The squadron granted pre-embarkation leave of ten days to all hands on 6 March. On the 19th, Ens. Jack Edwards, successfully landed an FM-2 in the water when his engine failed about 34 miles off Point Pinos. Attack transport Cullman (APA-78) steamed in the area and rescued Edwards after he spent only 16 minutes in his life raft. The Navy cancelled VC-7’s orders to Kitkun Bay on 13 April, however, and the men and planes of the squadron subsequently served on board other ships and stations.

Kitkun Bay wrapped-up the yard work and stood out of San Pedro with a full load of planes and carried them to Hawaiian waters (27 April–3 May 1945). The ship delivered her cargo to Pearl Harbor and into the following week cleaned-up from the repairs. In the process, yard workers at Pearl Harbor discovered that she required more work on the engines and the radar gear, which delayed her departure. Kitkun Bay returned to sea for a post-trial run on 3 June, during which she also carried our drills and gunnery exercises. The veteran ship slipped back into the harbor that evening to enable the navy yard to complete some engineering work. She loaded provisions and ammunition, along with the FM-2s, TBM-3s, and a single TBM-1C of VC-63, which had flown from NAS Hilo on Hawaii. The carrier then (8–13 June) took part in training exercises in the operating area west of Oahu.

On the 9th, Ens. Max I. Polkowski of VC-63 wrecked in a TBM-3E (BuNo 85735) he flew from the ship, but a destroyer rescued the pilot. The string of ill fortune continued as just the very next day, Lt. (j.g.) Richard C. Bunten, USNR, of VC-63 crashed in a Wildcat (BuNo 74781), but a destroyer retrieved Bunten from the water as well.

Kitkun Bay returned to Pearl Harbor and at 0800 on 15 June 1945, stood down the channel and steamed independently to Guam, holding frequent gunnery drills en route (15–27 June). The ship anchored in the harbor at Apra, and the next day unloaded her squadron and took fuel on board. Kitkun Bay proceeded to Ulithi, but while en route on the 28th, Ens. Walter R. Winiecki, USNR, of VC-63 went down in an FM-2 Wildcat (BuNo 74798), but a destroyer pulled the pilot from the sea and later returned him to the ship. Kitkun Bay reported to Third Fleet Logistic Support Group, TF 30.8, Rear Adm. Donald B. Beary, on the 29th, and loaded provisions and topped off fuel while at the atoll.

The ship joined Steamer Bay (CVE-87) and some other vessels and cleared Ulithi on 3 July 1945, and about three hours later, they formed Carrier Cover Unit, TU 30.8.23, to take part in raids against the Japanese home islands. The Allies planned to invade Japan through two principal plans: Operation Olympic—landings on Kyushu scheduled for 1 November 1945; and Coronet—landings on Honshū scheduled for 1 March 1946. Olympic included a diversion against Shikoku to precede the main landings, and the enemy prepared to defend the islands ferociously. “The sooner [the Americans] come, the better…One hundred million die proudly,” a Japanese slogan exhorted their people. The enemy deployed massed formations of kamikazes, as well as kaiten manned suicide torpedoes, shinyo suicide motorboats, and human mines—soldiers were to strap explosives to their bodies and crawl beneath Allied tanks and vehicles.

The preparations to support these landings included a series of carrier and surface raids by Halsey’s Third Fleet against Japanese airfields, ships, and installations from Kyūshū to Hokkaido. Flt. Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet, defined Halsey’s mission as to: “attack Japanese naval and air forces, shipping, shipyards, and coastal objectives,” and to “cover and support Ryukyus forces.” As part of this massive undertaking, McCain sailed with TF 38 from Leyte on 1 July 1945. The three task groups under McCain’s command, Rear Adm. Thomas Sprague’s TG 38.1, Rear Adm. Gerald F. Bogan’s TG 38.3, and Rear Adm. Arthur W. Radford’s TG 38.4, each comprised an average of three Essex (CV-9)-class carriers and two small carriers. A replenishment group and an antisubmarine group each included escort carriers.

Kitkun Bay and Steamer Bay shared launching daily CAP and antisubmarine patrols, and rendezvoused with other ships of TF 38 on 8 July. That night the reinforced task force fueled and turned toward the first battles of the voyage, when, on 10 July, they hurled strikes against Japanese airfields in the Tōkyō plains area. The enemy camouflaged and dispersed most of their planes, reducing the aerial opposition encountered but also diminishing the results obtained. Lt. Herbert Tonry, USNR, of VC-63 went down in an FM-2 Wildcat (BuNo 74923) he flew from Kitkun Bay on the 12th, but a destroyer rescued the pilot. Harsh weather compelled the Americans to shift their attacks to airfields, vessels, and railroads in northern Honshū and Hokkaido (14–15 July), and these two days of raids wrought havoc with the vital shipment of Japanese coal across the Tsugaru Strait.

Allied carrier planes bombed targets around Tōkyō on 17 July, and night CAP of planes flying from Bon Homme Richard (CV-31) protected U.S. and British ships that shelled six major industrial plants in the Mito-Hitachi area of Honshū. The following day, the carriers launched aircraft against the naval station at Yokosuka and airfields near Tōkyō. The raiders sank training cruiser Kasuga, incomplete escort destroyer Yaezakura, submarine I-372, submarine chaser Harushima, auxiliary patrol vessels Pa No. 37, Pa No. 110, and Pa No. 122, and motor torpedo boat Gyoraitei No. 28, and damaged Nagato, target ship Yakaze, motor torpedo boat Gyoraitei No. 256, landing ship T.110, and auxiliary submarine chaser Cha 225. Carrier raids damaged battleship Haruna and carriers Amagi and Katsuragi on 19 July. Kitkun Bay and Steamer Bay sent their planes aloft daily to protect the other ships from enemy aircraft or submarines.

Kitkun Bay and her consorts protected the group until they rendezvoused with the heavy carriers of the task force and replenished on 20 July 1945. Two days later, McCain set out for more raids and on 24 July attacked Japanese airfields and shipping along the Inland Sea and northern Kyūshū, supported by long-range strikes by USAAF bombers. Carrier planes flew 1,747 sorties and sank 21 ships including battleship Hyūga, Tone, training cruiser Iwate, and target ship Settsu, and damaged 17 vessels. The carriers repeated their sweep the following day. Carrier planes struck targets between Nagoya and northern Kyūshū on 28 July, sinking a number of ships including Haruna, Ise, training ship Izumo, Aoba, light cruiser Ōyodo, escort destroyer Nashi, submarine I-404, and submarine depot ship Komahashi. Aircraft damaged additional vessels.

The ship’s planes and escort ships often sighted and sank mines. Despite their maneuvering at times 400–500 miles from the Japanese home islands, the Carrier Cover Unit never encountered opposition. Kitkun Bay operated about 450 miles to the southeast of Honshū, in the vicinity of the Third Fleet rendezvous, as part of the Logistics Support Group, and took part in the third replenishment rendezvous on the last day of the month A typhoon approached the Third Fleet but Halsey brought the ships about on 31 July and 1 August southward to a position near 25°N, 137°E, to evade the tempest. On the evening of the 3rd, the task force departed for another series of strikes. The following day, Kitkun Bay, Nehenta Bay, Carlson (DE-9), and Dionne (DE-261) formed TU 30.18.27 and came about for Eniwetok.

A forge in Kitkun Bay’s shipfitter’s shop exploded at 1034 on 4 August 1945. The blast caused a fire and burned several men, and two sailors trapped by the fire in that area jumped overboard to avoid the flames. Dionne swung around and rescued both men, and later returned them to the carrier. The conflagration fatally burned one of the victims, but firefighters quickly extinguished the blaze. Kitkun Bay sighted Eniwetok at daybreak on the 9th, and the task unit was dissolved as the ships proceeded individually and anchored at the atoll. Capt. John S. Greenslade relieved Capt. Handly two days later, and Handly proudly announced that he turned over a “fighting crew and a fighting ship.”

While the ship prepared to rejoin the carrier sweeps against the Japanese home islands, she received news of the enemy’s willingness to surrender. Kitkun Bay then loaded foul weather gear because she received orders to turn northward and serve under Vice Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher, Commander, Ninth Fleet, and Alaskan Sea Frontier. Fanshaw Bay, Kitkun Bay, and their escorts formed TU 49.5.2 and set out at 0700 on 16 August for their northern journey. The two carriers operated as the duty carrier on alternate days during the voyage, but foul weather pummeled the ships and prevented flight operations.

The seasoned warships steamed through Amutka Pass and entered the Bering Sea on 23 August, and the next morning Kitkun Bay moored to a buoy in Kulak Bay on the Bering (northwestern) side of Adak Island in the Aleutians. The vessels anchored in the shadow of show-capped peaks surmounting the treeless green tundra, and refueled and loaded supplies. Kitkun Bay shifted to Sweeper’s Cove at Adak, where nearly 6,000 soldiers toured the ship the following day. That evening she cast off from the pier and returned to Kulak Bay.

From there, Fanshaw Bay, Hoggatt Bay (CVE-75), Kitkun Bay, Manila Bay, Nehenta Bay, Savo Island, and their screen including Chester (CA-27), Pensacola (CA-24), and Salt Lake City (CA-25), sailed in TF 49, Rear Adm. Harold M. Martin, Commander, CarDiv 23, who broke his flag in Hoggatt Bay, and participated in the occupation of the northern Japanese home islands (31 August–9 September 1945). Later that day, the task force was redesignated TF 44, and operated within range of Vice Adm. Fletcher, who hoisted his flag in amphibious force flagship Panamint (AGC-13). Fletcher set out to receive the formal Japanese surrender of their forces in northern Honshū and Hokkaido.

The carriers launched daily CAP and antisubmarine patrols, and the aircraft and ships sighted and destroyed frequent mines en route. An Avenger flying from Kitkun Bay became unable to maintain altitude while attempting an emergency landing on 5 September. The torpedo bomber crashed into the sea as the pilot turned to clear the ship’s stern, and Fullam (DD-474) raced over and rescued all three men, and returned the shaken but uninjured crew to the carrier within the hour. Before dawn on the 7th, Kitkun Bay detected a small Japanese patrol craft 3,000 yards on the beam. One of the destroyers intercepted and investigated the vessel, and the convoy continued the voyage.