H. L. Hunley

(Length 43'; beam 3'7"; draft 6'; speed 4 knots; complement 9; class H. L. Hunley)

Horace Lawson Hunley was born on 29 December 1823, in Sumner County, Tenn. He early moved to New Orleans, La., where he practiced law and represented Orleans Parish in the Louisiana State Legislature. On the outbreak of the Civil War, he joined James R. McClintock and Baxter Watson in sponsoring the building of Confederate privateer submarine Pioneer, later scuttled to prevent her capture when New Orleans fell. The three men built a second submarine at Mobile, Ala., but she sank in Mobile Bay. Hunley then provided the entire means for building a third submarine, named H. L. Hunley in his honor. The boat was privately built in the spring of 1863 in the machine shop of Park and Lyons, Mobile, Ala., under the direction of Confederate Army Engineers, Lt. W. A. Alexander and Lt. G. E. Dixon, 21st Alabama Volunteer Regiment, from plans that Hunley, James R. McClintock, and Baxter Watson furnished.

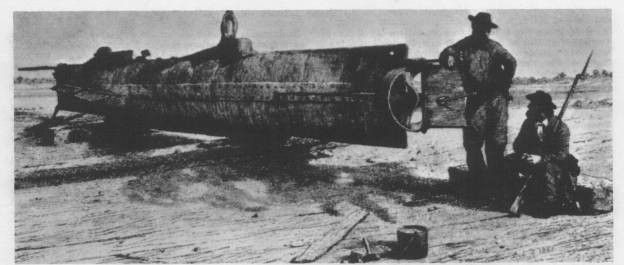

H. L. Hunley was fashioned from a cylindrical iron steam boiler as the main center section, with tapered ends added, and expressly built for hand-power. She was designed for a crew of 9 men - eight to turn the hand-cranked propeller and one to steer and direct the boat. A true submarine, she had ballast tanks at each tapered end which could be flooded by valves or pumped dry by hand pumps. Iron weights were bolted as extra ballast to the underside of her hull; these could be dropped off by unscrewing the heads of the bolts from inside the submarine if she needed additional buoyancy to rise in an emergency. H. L. Hunley was equipped with a mercury depth gage, was steered by a compass when submerged, and a candle provided light - and its dying flame would also warn the crewmen of their dwindling air supply. When near the surface, two hollow pipes equipped with stop cocks could be raised above the surface to admit air. Glass portholes in the combings of her two manholes were used to sight from when operating near the surface with only the manholes protruding above the water. Her original armament was a floating copper cylinder torpedo with flaring triggers which was towed some 200 feet astern, the submarine to dive beneath the target ship, surface on the other side, and continue on course until the torpedo struck the ship and exploded.

Lt. Dixon carried out H. L. Hunley’s trials in Mobile Bay, and on 7 August 1863, Gen. Pierre G.T. Beauregard, CSA, ordered railway agents to expedite the transportation of H. L. Hunley to Charleston, S.C., in order to help defend that city. She arrived in Charleston on two flat-cars and under the management of part-owners, B. A. Whitney, J. R. McClintock, B. Watson, and others unknown. Whitney served as a member of the Secret Service Corps of the Confederate States Army, his compensation to be half the value of any Union property destroyed by torpedoes or submarine devices.

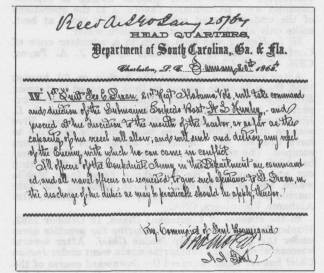

Finding the intended target, Union blockader New Ironsides, in too shallow water for the submarine to pass beneath her keel, the Confederates abandoned the torpedo-on-a-towline in favor of a spar torpedo, consisting of a copper cylinder holding 90 pounds of powder and equipped with a barbed spike. The submarine would drive the torpedo into the target by ramming, back away, and by a line attached to the trigger, explode the charge from a safe distance. H. L. Hunley operated from Battery Marshall, Beach Inlet, Sullivan's Island, in Charleston Harbor, where the smooth waters of the interior channels proved particularly favorable to the operations of the under-powered submarine which could at best, make only about four knots in smooth water. Lt. J. A. Payne, CSN, of Confederate ironclad ram Chicora, soon commanded a volunteer crew.

After several dives about the harbor on 29 August 1863, the submarine moored by lines fastened to steamer Etiwan at the dock at Fort Johnson. The steamer unexpectedly moved away from the dock, drawing H. L. Hunley on her side and she filled and went down. Five of Chicora’s crewmen drowned but Payne and two other men escaped. The Confederates raised the submarine, and on 21 September 1863, turned her over to Hunley for fitting out and manning. He brought from Mobile men with previous experience in handling the submarine, to be commanded by Dixon.

In Dixon’s absence on 15 October 1863, however, Hunley took charge of the submarine for practice dives under receiving ship Indian Chief. Following several successful dives, the submarine again went under Indian Chief but air bubbles traced H. L. Hunley’s downward course, and she failed to surface. Hunley and his entire crew of seven men died, as the water was nine fathoms deep, preventing anyone from immediately aiding them.

The Confederates raised H. L. Hunley and Dixon and Alexander reconditioned the submarine, but Beauregard refused to permit her to dive again. She was fitted with a “Lee spar-torpedo” and adjusted to float on the surface, being ballasted down so that only her manholes showed above the water. For more than three months the submarine went out an average of four nights a week from Battery Marshall, Beach Inlet, Sullivan's Island. Steering compass bearings taken from the beach on Federal ships taking anchor for the night, she failed time and time again because of circumstances: the distance of the closest blockader often measured six or seven miles away, and the conditions of tide, wind and sea, or physical exhaustion of her crew, who sometimes found themselves in danger of being swept out to sea in their underpowered craft.

Then on the night of 17 February 1864, she attacked Union steam sloop-of-war Housatonic, which lay anchored in about 27 feet of water, some two miles from Battery Marshall in the north channel entrance to Charleston Harbor. Approaching silently through calm waters, H. L. Hunley made a daring attack in bright moonlight, approaching within a hundred yards of the blockader before Housatonic’s lookouts spied the Confederate submarine. By the time observers determined she was not a log or other harmless object, H. L. Hunley closed the range and the Northern sailors could not depress their heavy guns sufficiently to come to bear. The submarine approached the keel of her victim at right angles, and came under small arms fire from the watch officers and men of the Housatonic.

Housatonic slipped her cable in great haste to try to back away, but H. L. Hunley’s torpedo struck home under water just abaft the mizzenmast. A stunning crash of timbers and a muffled explosion like the report of a 12-pound howitzer erupted, and some of Housatonic’s crewmen reported pieces of timber hurtling to the top of the mizzenmast, while a dark column of smoke rose high in the sky. Housatonic settled rapidly to the bottom in the shallow water, five of her men dying in the explosion or by drowning, the survivors scrambling to the safety of the rigging, which remained above the water’s surface.

H. L. Hunley failed to return from her mission. The exact cause of her loss is not known; she may have gone down beneath Housatonic, or in backing away, been swamped by waves caused by her sinking victim; or she may have been swept out to sea. Her heroic crew wrote a new page in history as the first submarine to sink a warship in combat.

For additional information concerning the discovery and salvage of H. L. Hunley see: http://www.history.navy.mil/research/underwater-archaeology/sites-and-projects/ship-wrecksites/h-l-hunley.html

Detailed history under construction.

Updated by Mark L. Evans