America II (Id.No. 3006)

1917-1919

The second America retained the anglicized form of the name she carried at the time of her acquisition.

II

(Id.No. 3006: displacement 41,500; 1ength 687'; beam 75'5"; draft 39'51/4"; speed 17.5 knots; complement 994; armament 4 6-inch, 2 1-pounders, 2 .30-caliber Colt machine guns, 1 .30-caliber Lewis machine gun, 9 depth charges)

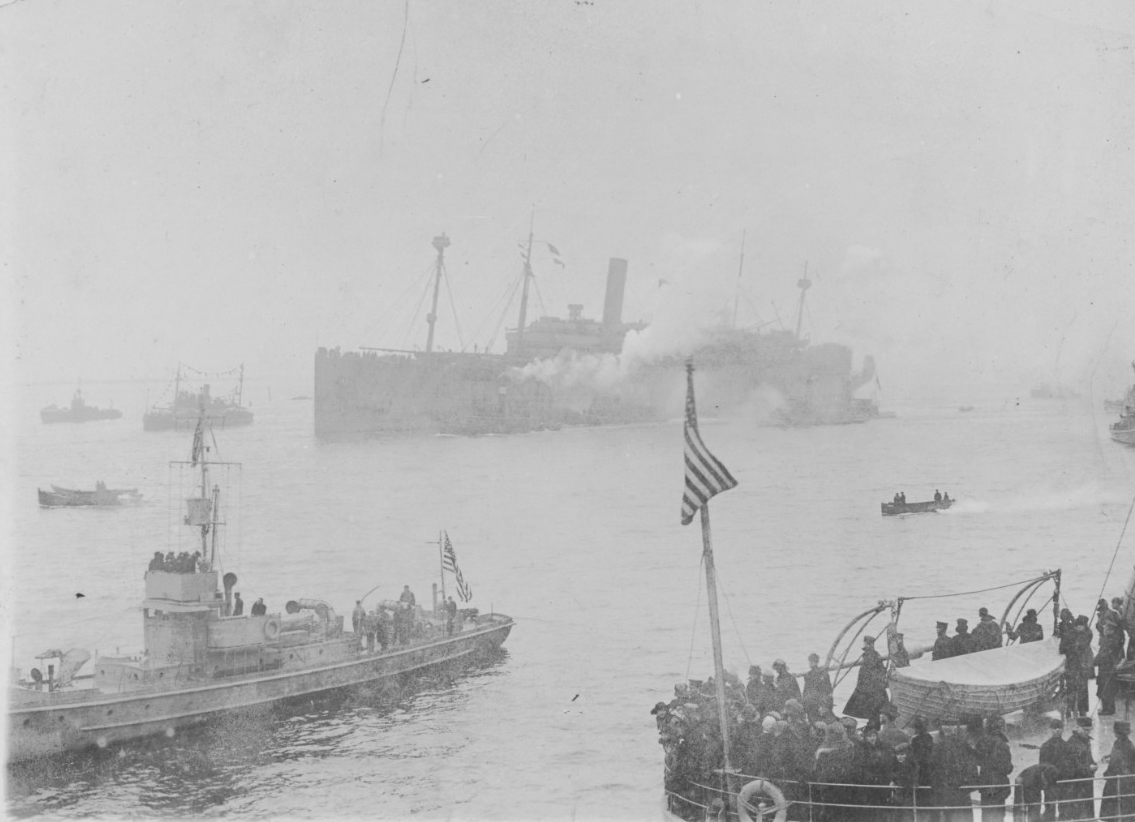

Amerika, a steel-hulled, twin-screw, steam passenger liner, was launched on 20 April 1905 at Belfast, Ireland, by the noted shipbuilding firm of Harland and Wolff, Ltd. Built for the Hamburg-America Line, the steamer entered transatlantic service in the autumn of 1905, when she departed Hamburg on 11 October, bound for the United States. The largest ship of her kind in the world, and easily one of the most luxurious passenger vessels to sail the seas, Amerika entered upper New York Bay on 20 October, reaching the Hamburg-America piers at Hoboken, N.J., in mid-afternoon. Some 2,000 people turned out to watch her as she was moored near her consorts at the Hamburg-America Line which were bedecked in colorful bunting in nearby slips.

Lavishly decorated throughout, Amerika boasted of a couple of unique shipboard features; an electric passenger elevator, and an a-la-carte restaurant which, from early morning to midnight, offered a variety of dishes to delight the discriminating gourmet.

From 1905 to 1914, Amerika plied the North Atlantic trade routes touching at Cherbourg, France, while steaming between Hamburg and New York. Toward the end of that period, her itinerary was altered so that the ship also called at Boulougne, France, and Southhampton, England.

However, during the summer of 1914, events in the Balkans triggered a conflict that soon spread through Europe like wildfire across a dry prairie, pitting nations against nations in a World War. The eruption of fighting caught Amerika at Boston, Mass., where she was preparing to sail for home. Although due to leave port on 1 August 1914, Amerika stayed at Boston lest she fall prey to the warships of the Royal Navy. She would remain there through almost three years of U.S. neutrality.

Meanwhile, the loss of life caused by German submarine operations turned opinion in the United States against the Central Powers; and American intervention in the conflict drew inexorably closer. Finally, on 6 April 1917, soon after Germany's resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare on 1 February 1917, the United States declared war.

Laid up at Boston, Amerika remained inactive until seized by deputies under the orders of John A. Donald, the Commissioner of the United States Shipping Board (USSB), on 25 July 1917. Upon inspecting the liner, U.S. agents found her filthy and discovered that her crew had sabotaged certain elements of the ship's engineering plant. Nevertheless, with her officers and men detained on Deer Island, Amerika was earmarked by the Navy for service in the Cruiser-Transport Force as a troop transport. Given the identification number (Id.No.) 3006, Amerika was placed in commission at 0800 on 6 August 1917, at the Boston Navy Yard, Lt. Cmdr. Frederick L. Oliver in temporary command. Ten days later, Capt. George Calvin Day arrived on board and assumed command.

Over the ensuing weeks, the ship's force and a veritable army of workmen swarmed over the erstwhile luxury liner, converting her into a troopship. While this work was in progress, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels promulgated General Order No. 320, changing the names of several ex-German ships on 1 September 1917. Amerika became the less-teutonic America.

The major part of her conversion and repair work having been completed by late September, America ran a six-hour trial outside of Boston harbor on the morning of 29 September 1917. The results of the test reflected "great credit upon the machinery division" of the Boston Navy Yard, for the ship managed to make three more revolutions than she had ever made before. The completion of these trials proved to be a milestone in the reconditioning of the former German ships, for America was the last to be readied for service in the American Navy.

On 18 October 1917, America departed the Boston Navy Yard and, on the 20th, arrived at Hoboken which would be the port of embarkation for all of her wartime voyages carrying doughboys to Europe. There, she loaded coal and cargo; received a brief visit from Rear Admiral Albert Cleaves, the commander of the Cruiser-Transport Force; and took on board her first contingent of troops. Completing the embarkation on the afternoon of the 29th, America sailed for France on the morning of the 31st, in company with the transports Mount Vernon, Von Steuben (Id.No. 3017), Agamemnon (Id.No. 3004), North Carolina (Armored Cruiser No. 12), Terry (Destroyer No. 25), and Duncan (Destroyer No. 46).

For more than a week, the passage was uneventful. Then, on the 7th, Von Steuben struck Agamemnon while zig-zagging. As America's war history states: "The excitement caused by the collision of these great ships was greatly increased when the Von Steuben sent out a signal that a submarine was sighted." The ships in the convoy dispersed as if on signal, only to draw together in formation once more when the "enemy" failed to materialize. All vessels resumed their stations, all, that is, except Von Steuben whose bow as open to the sea from the damage suffered in the collision. Even the crippled transport rejoined the convoy the following afternoon. Met on the 12th off the coast of France by an escort consisting of converted American yachts and French airplanes and destroyers, the convoy reached safe haven at Brest, America's only wartime port of debarkation. She dropped her anchor at 1115 and began discharging the soldiers who would fight "to make the world safe for democracy."

Underway again on 29 November 1917, the ship returned to the United States, in convoy, reaching Hoboken on 10 December. She then remained pierside through Christmas and New Year's Day and headed for France again on 4 January 1918, carrying 3,838 troops and 4,100 tons of cargo. The following day, she fell in with the transport Mercury (Id. No. 3012) and Seattle (Armored Cruiser No. 11), her escort for the crossing. Except for the after control station personnel reporting a torpedo track crossing in the ship's wake on 17 January-shortly before the transport reached Brest-this voyage was uneventful.

America arrived at Hampton Roads, Va., on 6 February and the next day entered the Norfolk Navy Yard for repairs and alterations. At this time, the ship received an additional pair of 6-inch guns to augment her main battery.

Shifting up the eastern seaboard to Hoboken where she again loaded doughboys bound "over there," America, carrying 3,877 troops, got underway on 27 February in company with her old consorts Agamemnon and Mount Vernon, and reached Brest on 10 March. After disembarking the troops, she took on board passengers who included French naval personnel, 4 officers, 10 petty officers, and 77 men, perhaps crews to man some of the submarine chasers then being built in the United States for the French Navy. Underway on 17 March, America reached home after a 10-day crossing.

The "trooping" continued as America embarked a further 3,877 troops before sailing for France on 6 April 1918. Joining Great Northern, on the 8th and Agamemnon on the 12th, America made port on 15 April. A week later, after disembarking her charges, the transport took on board the survivors from the American munitions ship, Florence H, which had exploded at Quiberon Bay five days before, and sailed for the United States.

Entering the Hudson River on 1 May 1918, America remained in port a week, embarking troops and undergoing routine voyage repairs, before sailing for France in company with George Washington (Id No. 3018). De Kalb (Id. No. 3010), coming from Newport News, Va., joined the two ships on the 10th; and the three continued on their voyage together. Shortly after 0300 on 18 May, De Kalb's quartermaster sighted what appeared to be a periscope some 50 yards from the ship. Two lookouts and an Army sentry reported seeing the same thing; and, a few moments later, the transport sounded the general quarters. However, as all hands manned their battle stations as ships turned to port, the "periscope" vanished-perhaps the product of overactive imaginations. In any event, later that day, the three transports reached Brest and began discharging cargo and disembarking the valuable troops she had carried.

After only a three-day turnaround period, America sailed for the United States, at 1550 on 21 May 1918, again in company with George Washington and De Kalb, and an escort of destroyers to shepherd them through the dangerous coastal waters. Trouble was not long in coming. Four hours out, one of the escorts, on the right flank, let a round fly at an object supposed to be a "submarine." Three of the destroyers fell back, opened fire, and dropped depth charges. Apparently, whatever had triggered the destroyers' alarm soon vanished; and the convoy proceeded on, unmolested. The destroyer escort left the convoy to its own devices after 2200 on 22 May, and the transports themselves parted company on the 23d, De Kalb dropping back and George Washington remaining slightly in the lead, until, on the 25th, America found herself steaming alone. On the afternoon of the 29th, she reached Hoboken without incident.

America commenced her sixth voyage on 10 June, clearing the port of embarkation with 5,305 troops on board, and in company with her old consorts Mount Vernon and Agamemnon, as well as Orizaba (Id No. 1536). Joined in European waters by their coastal escort eight days later, the transports safely reached Brest on 19 June and began to disembark and unload. America sailed for the United States in company with Orizaba, on the 23d, parted company with that ship three days later, and arrived at Hoboken on 1 July.

During the brief respite that followed, America briefly received Rear Adm. Gleaves on board and was painted in a "dazzle" camouflage pattern designed to obscure the ship's lines, a pattern that she would wear for the remainder of her days as a wartime transport.

Late on 9 July 1918, America sailed on the seventh of her voyages to Europe for the Navy. Just before midnight on the 14th, while the convoy steamed through a storm that limited visibility severely, a stranger, the steamship Instructor, unwittingly wandered into the formation and ran afoul of America. In spite of attempts at radical course changes by both ships, America struck the intruder near the break of her poop and sheared off her stern which sank almost immediately. America's swing threw the wreck of Instructor clear, allowing it to pass down the transport's port side without touching before it sank less than 10 minutes later. America stopped briefly to search for survivors, but the danger of lurking U-boats limited the pause to the most abbreviated of durations, and the storm added other obstacles. As a result, America succeeded in rescuing only the 11 Instructor crewmen who managed to man a lifeboat. Tragically, the exigencies of war forced America to abandon the other 31 to their fate. A court of inquiry held at Brest on 18 July, soon after America arrived there, exonerated her captain from any blame with regard to the sad incident.

Fortunately, since the brush with Instructor had caused but "trifling" damage to America, the transport was still able to carry out her mission. After embarking passengers for the return trip, she got underway on 25 July 1918 in company with Matsonia (Id. No. 1589), Manchuria (Id. No. 1633), Aeolus (Id. No. 3005), Sierra (Id. No. 1634), Martha Washington (Id. No. 3019), Powhatan (Id. No. 3013), and SS Patria. Upon parting from these ships three days later, America raced on alone and reached Hoboken on the evening of 3 August.

Her eighth voyage began on 18 August 1918 with America's sailing in company with George Washington and Von Steuben. She reached Brest on the 27th, discharged her troops, and embarked the usual mix of passengers. On this trip, she took on board 171 army officers, 165 army enlisted men, 18 French nuns, 10 YMCA secretaries, a Red Cross official and two nurses, two civilians and two sailors before sailing on 30 August. One of the civilians was the distinguished conductor, Dr. Walter Damrosch (1862-1950) who, at the request of General John J. Pershing, commanding general of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) was entrusted the mission of reorganizing the bands of the Army and had founded a school for bandmasters at the general headquarters of the AEF at Chaumont, France.

America parted from George Washington and Von Steuben on 2 September 1918 and reached the Boston Navy Yard on the 7th. Following drydocking, voyage repairs, and the embarkation of another contingent of troops, she arrived at Hoboken on the morning of the 17th. Three days later, she cleared the port, in company with Agamemnon, bound for France on her ninth transatlantic voyage cycle.

By this time, an influenza epidemic was raging in the United States and Europe and had taken countless lives. From its first appearance, special precautions had been taken on board America to protect both her ship's company and passengers from this scourge. The sanitary measures had succeeded in keeping all in the ship healthy. However, this group of soldiers, who had come on board at Boston where the epidemic had been raging, brought the "flu." As a result, 997 cases of "flu" and pneumonia occurred among the embarked soldiers during the passage to France, while 56 cases broke out among the 940 men in the crew. Before the transport completed the round-trip voyage and arrived back at Hoboken, 53 soldiers and 2 sailors had died on board. This comparatively low death rate (some ships lost considerably more men) can be attributed to the almost super-human efforts of the ship's doctors and corpsmen, as well as the embarked units' medical personnel. Forty-two of the 53 deaths among the troops occurred during the time the ship lay at anchor at Brest from 29 September to 2 October.

The day after reaching home, America commenced coaling and loading stores in preparation for her 10th voyage and completed the task at 0225 on 15 October. In addition, the ship was thoroughly fumigated to rid her of influenza germs. By that time, all troops had been embarked and the ship loaded, ready to sail for France soon thereafter.

At 0445, as the first rays of sunlight began to streak the eastern sky, America, without warning, began listing to port and kept heeling over as water cascaded through the coaling ports, still open although the fueling evolution had been completed over two hours before. Soon after the ship began listing, the general alarm was sounded throughout the ship. In the troop spaces, the urgent sound of that alarm awakened the sleeping soldiers who, though scantily clad, tumbled from their bunks and sought egress from their compartments. Soldiers and sailors both streamed up ladders topside; others jumped for safety on the coal barges, still alongside, or down cargo nets to the dock. Sentries on deck fired their rifles in the air to add to the din as they, in that fashion, sought to warn their comrades on board.

Cmdr. Edward C. S. Baker, the executive officer, in the absence of Capt. Zeno E. Briggs whose wife was seriously ill, directed Lt. John G. M. Stone, the gunnery officer, to clear the lower compartments. Stone performed his duty magnificently, and was credited with leading to safety many soldiers and sailors who had been blindly plunging through various compartments (the flooding of the engine rooms had put the lights out throughout the ship) seeking some means of escape.

Rear Adm. Gleaves arrived at the dock soon after the ship sank, the water covering her main deck, to see personally what had happened to one of the largest transports in the Cruiser-Transport Force. Before the day was out, a court of inquiry began meeting to determine what had happened. Over the ensuing days, salvage efforts continued, including the removal of guns, cargo, and other equipment, as well as the search for the six men unaccounted for at muster. Eventually, the bodies of all, four soldiers and two sailors, were recovered. Divers worked continuously, closing open ports (almost all on "G" deck had been left open to allow the air to be cleared of the smell of disinfectants that had been used to cleanse and fumigate the compartments). She was raised and refloated on 21 November 1918-10 days after the armistice was signed ending World War I. On 16 December, America was towed by 10 tugs to the New York Navy Yard where she remained undergoing the extensive repairs occasioned by her sinking, well into February 1919.

While unable to determine definitely what had caused the sinking, the court of inquiry posited that water had entered the ship through open ports on "G" deck. An "unofficial opinion" held by some officers in the case maintained that the listing of the ship had been caused by mud suction, that the ship, to some extent, had been resting on the bottom, and that, when the tide rose, one side was released before the other.

Foreshadowing the "Magic Carpet" operations which would follow World War II, a massive effort was made after the armistice to return the veterans of the American Expeditionary Force to home. America participated in this gigantic effort which commenced for her on 21 February when the ship sailed for Brest, France, and concluded on 15 September. Between that time, the transport made eight round-trip voyages to Brest. The western terminus was Hoboken for seven voyages and Boston for the other. Among the 46,823 passengers whom she brought back from France in America was Mr. Benedict Crowell, the Assistant Secretary of War who was embarked in the ship during her last voyage as a Navy transport.

On 22 September 1919, shortly after America completed that voyage, the Chief of the Army Transportation Service (ATS), Brigadier General Frank T. Hines, General Staff, U.S. Army, contacted the Navy, expressing the Army's desire to acquire America and Mount Vernon ". . . to transport certain passengers from Europe to the United States." Four days later, America was decommissioned while alongside Pier 2, Hoboken, and transferred to the War Department. Capt. J. Ford, ATS, simultaneously assumed command of the ship.

USAT America conducted two more voyages between Hoboken and Brest. Trouble highlighted her second voyage under the Army colors. An unruly crew at Brest on 4 December 1919 prompted Capt. Ford to appeal to the colonel commanding Base ection Number Five, at Brest, for an armed guard, fearing mutiny. Apparently, the Army matter was resolved, for the ship reached Hoboken five days before Christmas 1919.

On 20 December, the day America was scheduled to arrive at the port of debarkation, arrangements were made to turn America and two other Army transports, USAT President Grant and USAT George Washington, over to the USSB for operation while they were being carried on the roll of the Army Transport Reserve. However, before the year 1919 was out, events in a faraway land caused a temporary change in this plan.

A glance back at developments on the Eastern Front during World War I may clarify the transport's new mission. When it mobilized for war, the Austria-Hungarian Empire conscripted countless Czechs. Upon reaching the front, these men, long restive under Austrian rule, deserted in droves and then were organized by Russian officers to fight their former masters. However, the war sapped away the strength of the Russian government more rapidly than it weakened those of the other belligerents and thus encouraged rebellion. One revolution early in 1917 toppled the Czar and a second in the autumn placed a Bolshevik regime in power. The communist leaders quickly negotiated with Germany the treaty of Brest-Litovsk which took Russia out of the war and allowed the Central Powers to concentrate their resources on the Western Front.

This development left the Czech Legion, some 40,000 strong, stranded in Russia with hostile forces separating it from its still oppressed homeland. Allied leaders hoped to use these dedicated and highly disciplined fighting men to bolster their own embattled troops on the Western Front and encouraged the Czechs to move east on the Trans-Siberian Railroad to Vladivostok where they could be embarked in transports for passage to France.

However, before this could be accomplished, the Czechs, who had tried to remain aloof from Russia's internal struggles, incurred the hostility and opposition of the Bolsheviks and found themselves involuntarily embroiled in the Russian Civil War as something of a rallying point for various counterrevolutionary forces. Moreover, prior to the armistice, some factions within the Allied Powers hoped that the Czechs might be used to reopen the fighting on the Eastern front against the Central Powers. As a result, some two tempestuous years passed before the entire Czech Legion finally assembled at Vladivostok ready for evacuation.

On 30 December 1919, a representative of the War Department contacted the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations stating that USAT America and USAT President Grant "were to go on a long secret trip as soon as possible." He emphasized the urgency of the situation and requested that the New York Navy Yard give the highest priority to repairing the two transports for sea. The Navy carried out the repairs, including dry-docking, at top speed and completed the work by 21 January 1920. Two days later, America shifted to Hoboken and sailed for the Pacific on 30 January.

America reached San Francisco on 16 February and remained there a week before clearing the Golden Gate on the 23d. Sailing via Cavite, in the Philippines (where she tarried from 15 to 23 March), and Nagasaki, Japan, America reached Vladivostok soon thereafter.

While the transport had been on her way to the Russian Far Eastern port, the situation in Russia had deteriorated markedly. Bolshevik armies had driven the White Russian forces back into Siberia, and the collapse of the White government, headed by Admiral Alexander Kolchak, sounded the death knell of the western attempt to intervene in the Civil War. By the time the ship arrived at Vladivostok, the evacuation of the Czech Legion was well underway. Adding to the number of people to be transported were the several hundred wives and children of Czech soldiers, since some 1,600 men had married during the period of the "Czech Anabasis" in Russia. By 20 May, the last of the Czech troops had arrived in Vladivostok. Five days later, the United States consul in that port estimated that some 13,200 remained to be repatriated in the five or six remaining transports, which included America. Ultimately, USAT Thomas and USAT America reached Trieste on 8 August, disembarking their contingents of Czechs without incident.

For America, further service, now in civilian livery, awaited. Reconditioned to resume her place in the transatlantic passenger trade, she commenced her maiden voyage as an American passenger liner on 22 June 1921, sailing for Bremen, Germany, with stops at Plymouth, England, and Cherbourg, France, en route.

For the next 11 years, America plied the Atlantic, ranking third only in size to the United States Lines' ships Leviathan and George Washington, the latter her erstwhile running mate from the Cruiser-Transport Force days. On two occasions, America figured in the headlines. The first occurred on 10 March 1926, as the ship lay moored in the yard of the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co., Newport News, Va., awaiting final trials after being reconditioned. A fire broke out on board only a day before she was to be returned to her owner. The blaze raged for seven hours and eventually consumed most of the passenger cabins as it swept the ship nearly from stem to stern, causing an estimated $2,000,000 worth of damage.

The second newsworthy incident began on 22 January 1929 when America-then commanded by Capt. George Fried, was steaming from France to New York. As she battled her way through a terrific storm, the liner picked up distress signals from the Italian steamship, Florida. Guided by her radio direction finder, the American ship homed in on the Italian and, late the following afternoon, finally sighted the endangered vessel through light snow squalls. Taking a position off Florida's weather beam, America lowered her number one lifeboat, commanded by her Chief Officer, Harry Manning, with a crew of eight men.

After the boat had been rowed to within 50 feet of the listing Florida, Manning had a line thrown across to the eager crew of the distressed freighter, some of whom were nearly naked, dazed, and hysterical from exposure. One by one, the 32 men from the Italian ship came across the rope. By the time the last of them, the ship's captain, had been dragged on board the pitching lifeboat, the winds had reached gale force, with violent snow and rain squalls, with a high, rough, sea running. Then, via ladders, "monkey ropes," cargo nets, and two "prized homemade breeches buoys," sailors on board America brought up Florida's survivors, until all 32 were safe and sound. Finally, they pulled their shipmates from the rescue party back on board. Chief Officer Manning was brought up last. Capt. Fried felt that it was highly dangerous to attempt to hoist the number one lifeboat on board and, rather than risk lives, ordered it cut adrift.

In 1931 and 1932, after two modern ships, Washington and Manhattan, had been added to the fleet of the United States Lines, America was laid up at Point Patience, Md., on the Patuxent River, along with her consorts of days gone by, George Washington, Agamemnon, and Mount Vernon, all veterans of the old Cruiser-Transport Force. For the next eight years, America lay in reserve, riding quietly at her moorings as she awaited the call back to service.

When the United States transferred 50 overage "flush deckers" to the British government in the summer of 1940 in exchange for leases to strategic base sites in the Atlantic, one of the acquisitions was St. John's, Newfoundland. Now bases require garrisons; garrisons require troops; and troops require barracks. But no barracks existed at St. John's, so an interim solution had to be provided.

As a result, in October 1940, America was towed to Baltimore, Md., to undergo rehabilitation in the Bethlehem Steel Company yard. Earmarked for use as a floating barracks, the ship would provide quarters for 1,200 troops, the garrison for the new base at St. John's. Still a coal-burner, the ship could only make a shadow of her formerly magnificent speed, 10 knots.

With the ship's new role came a new name. Possibly to avoid confusion with the liner America, then building at Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Co., the transport's name was changed to Edmund B. Alexander, in keeping with the Army's policy of naming its oceangoing transports for famous general officers. This name honored Edmund Brooke Alexander (1800-1888), who had been brevetted major at Cerro Gordo (18 April 1847) and lieutenant colonel at Contreras and Churubusco (20 August 1847), in the war with Mexico. During the Civil War, he had served as provost marshal in St. Louis, Mo., performing his "delicate and important duties" in a way that merited "the favor of both friend and foe" alike.

Ready for her new duties by January 1941, Edmund B. Alexander sailed for Newfoundland, escorted by USCGC Duane. She remained there, a floating barracks, until quarters to house the troops had been constructed on shore. At that time, June 1941, she returned to New York.

Extensive repairs in the yards of the Atlantic Basin Iron Works followed. The ship operated briefly between New Orleans and the Panama Canal Zone. Subsequently ordered to Baltimore in May 1942, Edmund B. Alexander spent almost a year undergoing a major facelifting, as well as internal work. During the overhaul, she acquired a single funnel, replacing the two, and was converted to burn oil fuel instead of coal. Most importantly, she could now turn up the speed she used to make as one of the premier ocean liners of her day, 17 knots.

Edmund B. Alexander carried troops between New York and the European and Mediterranean theaters for the remainder of World War II. Altered during February and March 1946 to carry military dependents (904 adults, possibly war brides, and 314 children) back from Europe, she performed such duty for the next three years and was placed in reserve at Hawkins' Point, Md., on 26 May 1949. Taken thence on 28 January 1951 to lay-up in the Hudson River, Edmund B. Alexander remained there for almost six more years.

This time the call back to active service never sounded. The venerable ship was sold to the Bethlehem Steel Co., of Baltimore, on 16 January 1957 and was broken up under the scrapper's torch a short time later.