Tennessee IV (Armored Cruiser No. 10)

1906-1917

The fourth U.S. Navy ship named for the 16th State of the Union.

IV

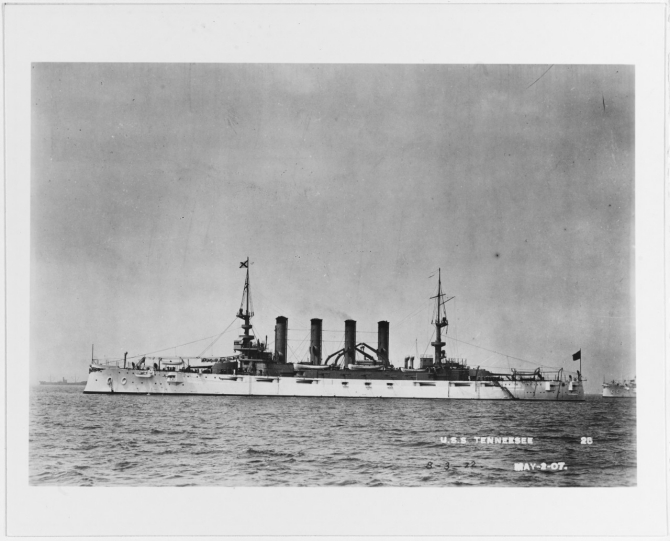

(Armored Cruiser No. 10: displacement 14,500; length 504'5"; beam 72'10½"; draft 25'; speed 22 knots; complement 829; armament 4 10-inch guns, 16 6-inch guns, 22 3-inch guns, 4 3pounder (saluting) 2 18-inch torpedo tubes (submerged); class Tennessee)

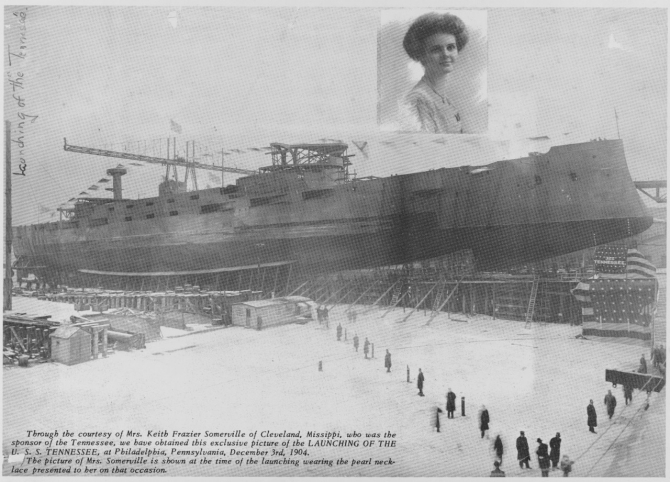

The fourth Tennessee (Armored Cruiser No. 10) was laid down on 20 June 1903 at Philadelphia, Pa., by the Cramp Shipbuilding Co.; launched on 3 December 1904; sponsored by Miss Annie K. Frazier, daughter of Governor James B. Frazier of Tennessee and subsequently the foundress of the Society of Sponsors of the United States Navy; and commissioned at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 17 July 1906, Capt. Albert G. Berry in command.

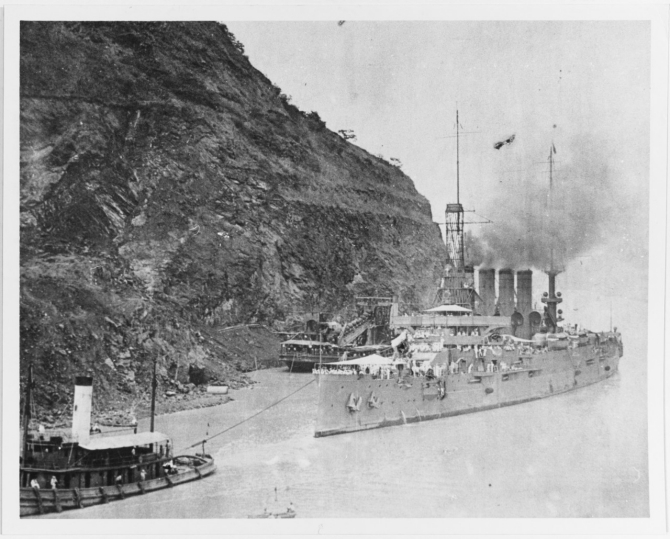

The new armored cruiser departed Hampton Roads, Va., on 8 November 1906 as escort for Louisiana (Battleship No. 19), in which President Theodore Roosevelt had embarked for a cruise to Panama to check on the progress of work constructing the isthmian canal. Tennessee briefly stopped at Piney Point, Md., visited Colón, at the Panama Canal (14–15 November), and Chiriqui Lagoon (16–17 November). After a brief visit to Puerto Rico on the return voyage (21–22 November), where the President studied the administrative structure of the Commonwealth’s government, the warships returned to Hampton Roads on 26 November.

Following repairs at League Island [Philadelphia] (18 December 1906–12 April 1907), Tennessee cleared Hampton Roads on 16 April 1907 for the Jamestown Exposition, held off Sewell’s Point, to commemorate the tri-centennial of the founding of the first English settlement in America. The ship participated in the fair (16 April–16 May), and then came about for New England waters, visiting Provincetown, Mass. (18–24 May), and undergoing repairs in dry dock at the Boston (Mass.) Navy Yard (25 May–5 June). Tennessee returned to the Jamestown Exposition (7–11 June), then sailed for Europe on 14 June in company with Washington (Armored Cruiser No. 11), reaching Royan, France, on 23 June for duty with the Special Service Squadron. She coaled at Ile D’Aix (2–3 July), then visited La Rochelle (3–11 July) and Brest (12–25 July) before returning home, carrying out speed trials off Tompkinsville, N.Y. (6–16 August). After visiting Newport, R.I., (18–19 August), Boston (20 August–30 September), and Newport (1–4 October), Tennessee lay to at Hampton Roads (5–12 October).

Assigned to the Pacific Fleet, Tennessee set sail from Hampton Roads on 12 October 1907, and visited Port of Spain, Trinidad, British West Indies (18–24 October), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (4–10 November), Montevideo, Uruguay (13–19 November), and Punta Arenas, Chile (23–27 November) en route. She called at Callao, Peru (5–12 December), where she served as the flagship of the Special Service Squadron, and rounded out her voyage by visiting Acapulco (19-22 December) and spending Christmas at Pichilinque, Mexico (25–28 December, respectively), before rendezvousing with Washington at Magdalena Bay, Mexico (29 December 1907–15 February 1908), and standing in to San Francisco, Calif., on 20 February 1908, where she became flagship for the Second Division of the Pacific Fleet.

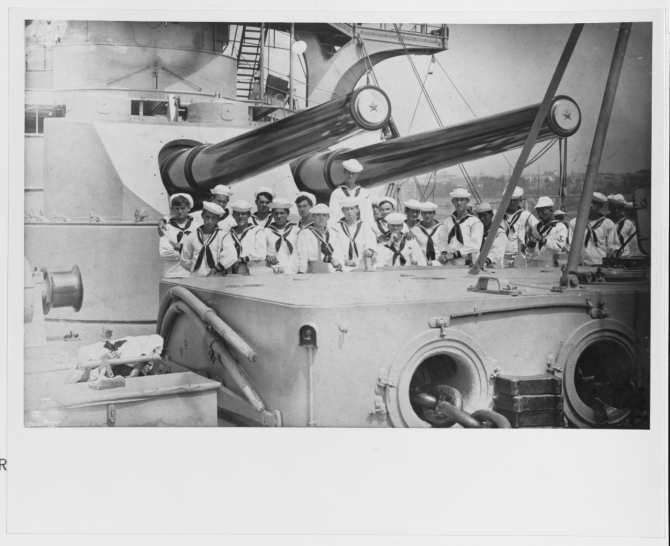

Tennessee conducted towing experiments with Preble (Destroyer No. 12) off San Francisco on 1 July 1908, and with Farragut (Torpedo Boat No. 11) off San Diego (3–7 July), then paused at San Francisco on 9 July, before coaling ship at California City, Calif. (9–10 July). She then cleared San Francisco on 12 July for Bremerton, Wash., in company with Washington. Following repairs and alterations at the Puget Sound Navy Yard, including the installation of electrical range finders and other fire control gear (14 July–16 August), the warship returned to San Francisco on 19 August to join the fleet, then sailed for Samoa on 24 August, with the eight heavy ships of the first and second divisions each towing a destroyer, with Tennessee towing Whipple (Destroyer No. 15). Pausing at Honolulu, Hi., en route (2–10 September), Tennessee, Washington, Hopkins (Destroyer No. 6), and Whipple ultimately reached Apia on 20 September, then shifted to Pago Pago, making port on 23 September, the Second Division conducting range finder experiments and other fire control training in between port visits. Underway for the Hawaiian Islands on 7 October, Tennessee returned to Honolulu on 17 October for a five-day visit, after which she towed Whipple to Magdalena Bay, Mexico (22 October–2 November).

Tennessee carried out target practice at Magdalena Bay (2 November–1 December 1908), after which the warships continued south, paying a visit to Amapala, Honduras (8–10 December) before continuing on and stopping at Colon, Panama, to observe progress on the trans-isthmus canal (13–22 December). After spending Christmas at sea, Tennessee anchored at Talcahuano, Chile, with the Pacific Fleet (3–14 January 1909), after which the Second Division put in to Coquimbo, Chile, in late January 1909. While there (16–22 January), the armored cruiser contributed a fire-brigade to help put out a major fire in the city. From Coquimbo, the division continued north, making stops at Callao (27 January–10 February), Stephen’s Bay, Chatham Island (14–18 February), Panama (22 February), coaling at Taboga, Panama (22–24 February), visiting Panama again with the Pacific Fleet (24 February–4 March), then pausing at Puntarenas, Costa Rica (6-10 March), before returning to Magdalena Bay for a month of target practice (17 March–17 April). After coaling ship at California City, Tennessee rejoined the Pacific Fleet at San Francisco on 22 April.

Tennessee departed San Francisco on 17 May 1909, and then visited Port Townsend, Wash. (20–21 May). She steamed thence to Tacoma, Wash., (21–29 May) and Seattle, Wash. (29 May–10 June), where she participated in receptions for a visiting Japanese Squadron. Following another trip to the Puget Sound Navy Yard for repairs and alterations (10 June–18 August), the armored cruiser participated in a fall cruise with other armored cruisers of the Pacific Fleet. After coaling and provisioning at San Francisco (31 August–5 September), the ships departed the west coast on 5 September. After a period in Hawaiian waters at Honolulu (10–20 September), Maalea Bay (20–22 September), Hilo (23–24 September), and Honolulu again (25 September–5 October), Tennessee steamed to the Admiralty Islands, coaling at Nares Harbor (17–25 October) before proceeding to the Philippine Islands.

Tennessee visited Manila (30 October–4 November 1909), to provide liberty for her crew, then coaled ship at Cavite (4–7 November), after which she conducted calibration practice off Olongapo (7–10 November). The armored cruiser returned to Manila, and there prepared for target practice (10–20 November), after which she conducted those evolutions, continuing that training off Olongapo (21 November–2 December), Cavite (2–5 December), and Olongapo again (5–6 December), compensating her compasses at Manila (6–10 December).

Cruising in company with Washington to Nimrod Sound, China (13–14 December 1909), to Woosung (Wusong), China (14–30 December), and to Heigun Island, in the Japanese Inland Sea (1–2 January 1910), Tennessee joined the Pacific Fleet at Yokohama, Japan (3–20 January). Steaming thence with the fleet, the ship paid a return call to Honolulu (31 January–8 February), then put in to Bremerton on 15 February for repairs and alterations at the Puget Sound Navy Yard.

Clearing Puget Sound on 19 March 1910, Tennessee and Washington proceeded to Panama, arriving there on 2 April. Steaming thence with South Dakota (Armored Cruiser No. 9) on 12 April, Tennessee set course for Maldonado, Uruguay, there to join the Special Service Squadron. Pausing en route at Punta Arenas, Chile (25 April–1 May), the two armored cruisers continued on, reaching Maldonado on 5 May, there joining Montana (Armored Cruiser No. 13) and North Carolina (Armored Cruiser No. 12). The four ships then steamed to Bahia Blanca to represent the United States at the centenary celebration of Argentine independence. While there (15 May–5 June), Tennessee hosted a luncheon for the Argentine Minister of Marine and the U.S., Japanese, and Cuban Consuls. The ships then steamed north to Montevideo, Uruguay (7–14 June), then to Rio de Janeiro, arriving on 17 June where they anchored near Brazilian battleship Minas Geraes. Proceeding to Hampton Roads, the squadron paused briefly at Culebra in the West Indies (12–18 July) before steaming into Hampton Roads on 22 July in company with Montana and North Carolina. With the disbanding of the Special Service Squadron, Tennessee became flagship for the fifth division of the Atlantic Fleet.

After coaling ship at Lambert Point, Va., the armored cruiser continued to serve as division flagship into mid-August 1910, conducting target practice on the Southern Drill Grounds (1–8 August), then coaling ship again at Lambert Point. On detached duty, Tennessee, again accompanied by Montana and North Carolina, visited a succession of ports in Maine -- Bar Harbor (16–22 August), Rockland (22–25 August), and Portland (25–26 August) -- before undergoing repairs at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, N.H. (27 August–31 October). Subsequently, Tennessee proceeded via Hampton Roads (2–6 November) to Charleston, S.C., where she embarked President William H. Taft (8–10 November) for a round-trip voyage to Panama to inspect progress on the canal, reaching Cristóbal with the presidential party on 14 November. Coaling ship at Porto Bello, she then re-embarked the Chief Executive at Cristóbal on 17 November. Pausing briefly at Guantánamo Bay (19 November), Tennessee then returned to Hampton Roads, disembarking President Taft and his entourage during that time (22 November–2 December).

Tennessee then prepared for battle practice, first at Lynnhaven Bay (2–5 December 1910), then on the Southern Drill Grounds (5–9 December), after which time she bore-sighted her guns in Hampton Roads (9–12 December). Putting to sea soon thereafter, she returned to the Southern Drill Grounds, holding battle practice between 12 and 20 December. She then stood in to Hampton Roads on 20 December to coal ship and take on stores, and to give her crew holiday liberty that lasted three days into the new year 1911.

Tennessee conducted a scouting problem upon clearing Hampton Roads on 3 January 1911, and set course for Cuban waters. She then operated from Guantánamo Bay (13 January–17 February), carrying out trials and battle exercises. Following a Mardi Gras visit to New Orleans, La. (21 February–1 March), and a call at New York City for liberty (6–9 March), the warship steamed to Cuban waters for special service with the Atlantic Fleet’s fifth division, three more months of operations out of Guantánamo Bay (13 March–10 June). On 10 June, Tennessee sailed north to Portsmouth where, after testing a submarine signal set off Nantucket Shoals Lightship, she was placed in reserve on 26 June 1911.

The armored cruiser remained at Portsmouth Navy Yard until 19 April 1912 when she got underway for the Boston Navy Yard, where she loaded 6-inch powder (19–21 April). Steaming thence to Newport, she took on board torpedoes and associated equipment (22–23 April). Tennessee reached the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 24 April, where she became flagship for the Commander in Chief of the Atlantic Reserve Fleet.

Departing Philadelphia on 1 August 1912, Tennessee set course for Newport, and there embarked a draft of apprentice seamen (3–10 August) for transport to Philadelphia, disembarking her passengers there on 12 August and returning to the Reserve Fleet, where she remained until 8 October. Clearing Philadelphia on that day, Tennessee participated in a naval review at New York City (10–15 October), after which time she returned to Philadelphia to resume her time in reserve (17 October–12 November).

Placed in full commission on 11 November 1912, Capt. Harry A. Field in command, Tennessee departed Philadelphia the next day for special service in the Mediterranean. Following a stop at Gibraltar to coal (21–24 November), the armored cruiser steamed to the port of Smyrna (Izmir) in the Ottoman Empire, arriving there on 1 December to protect Americans during the ongoing fighting between the Turks and Bulgarians during the Second Balkan War. Tennessee departed Anatolia on 3 May 1913 after the crisis had passed, proceeding back to the U.S. via Algiers, Algeria (8–13 May) and standing in to Hampton Roads on 25 May. In a familiar routing, the warship proceeded to the Portsmouth Navy Yard for repairs (8 June–21 October), going into reserve during that period, on 2 September, and then rejoining the Reserve Fleet at Philadelphia on 23 October 1913.

Detached from the Atlantic Reserve Fleet on 1 May 1914, Tennessee became the receiving ship at the New York Navy Yard the following day, serving as such until 29 May, when she got underway for the North River. There, she fired salutes off [Gen. Ulysses S.] Grant’s Tomb and the Soldiers and Sailors Monument on Memorial Day (29–31 May), after which she returned to the New York Navy Yard on 31 May.

Tennessee remained inactive until the outbreak of World War I in Europe during the summer of 1914. The war surprised thousands of Americans in Europe, some without access to money or credit, and all hampered by the disrupted steamship service in making their way home. In response, Tennessee embarked U.S. Treasury and banking officials, as well as nearly $3 million in relief aid for transport to Europe. Underway on 6 August 1914, the armored cruiser began a rapid transit across the Atlantic, arriving in Falmouth, England, on 16 August. Some of the gold and officials were then sent by special train to London. Putting to sea on 20 August, the warship picked her way through the English Channel, where she spotted numerous Royal Navy battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, before anchoring off the Hook of Holland, near Rotterdam, the following day. More funds for the American Relief Expedition were sent thence to The Hague before Tennessee returned to Falmouth eight days later.

As German troops advanced on Paris, Tennessee made two runs to Le Havre, France, from which she evacuated 400 Americans to Weymouth, England (1–6 September 1914). She remained there until 29 September, when reports of German submarines in proximity forced her to move to Falmouth. The next day, the ship received orders to proceed to Italy. Tennessee got underway on 3 October and arrived at Brindisi on 12 October. A week later, the armored cruiser steamed into the eastern Mediterranean, where she visited Beirut, Lebanon, a number of Greek Islands, and several ports in Anatolia, before reaching Alexandria, Egypt, on 16 December. The warship took on money and stores for distribution at Jaffa, Palestine, as well as mail for North Carolina, then at Beirut. She then made four trips carrying a total of 3,600 refugees from Jaffa to Alexandria, the last leg putting into Egypt on 30 January 1915. After a delay caused by Turkish officials denying permission for refugees to leave, Tennessee made a fifth evacuation run to Jaffa, carrying another 657 refugees (15–17 February). The warship remained in the region throughout the spring, steaming between Jaffa, Beirut, and Alexandria in support of refugee relief efforts, a task made more difficult since the war had embroiled the Turks. After transporting a final 124 passengers from Jaffa to Alexandria on 28 June, Tennessee sailed for home, proceeding via Barcelona, Spain, and Horta, Fayal, in the Azores, and reached New York on 30 July.

While the situation in Europe had deteriorated into war, closer to the U.S. in 1914 and 1915, Gen. Jean V. G. Sam of Haiti led a revolt and on 25 February 1915 was “elected” president of that island republic. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Rosalvo Bobo, increasingly frustrated with the country’s growing ties to the U.S., rebelled against Sam. The U.S. dispatched Rear Adm. William B. Caperton, Commander Cruiser Squadron, Atlantic Fleet -- his flag in Washington -- to Cap Haitien, where he arrived on 1 July with orders to keep the peace. Caperton landed a detachment of marines that established radio communication between his flagship and the U.S. consulate.

The violence ashore continued, however, largely as a result of bandit bands called cacos from the mountainous north, and Sam imposed harsh measures against his opponents. When firing erupted near the Presidential Palace on 27 July 1915, Sam ordered Gen. Charles O. Etienne, the Chief of Police of Port-au-Prince, to hang 167 prominent political hostages held in the National Penitentiary. The executions outraged many Haitians and a mob rampaged through the city. Sam and Etienne sought refuge in the French Embassy but the rioters dragged the men out and hacked them to pieces. Caperton landed two companies of marines and three of bluejackets under the command of Capt. George Van Orden, USMC, to secure the Haitian navy yard at Bizoton, three miles west of the capital, and to restore order, but the admiral requested reinforcements as the fighting spread. Additional forces reached the island during the following days, but Caperton requested more men.

After a short repair period at New York, Tennessee received orders to embark the Headquarters, 1st Marine Brigade (Col. Littleton W. T. Waller, USMC, in command), with eight companies of the 1st Marine Regiment, Marine Expeditionary Force (Col. Eli K. Cole, USMC, in command), and on 10 August sailed for Haiti. The ship there disembarked her marines and swung ‘round and returned to the United States to embark the Marine Artillery Battalion (Maj. Robert H. Dunlap, USMC, in command) and on 24 August sailed again for Haitian waters. By the end of the month, Waller led 2,029 men against the cacos and rioters. Prompted by Caperton, the Haitian Congress meanwhile elected Philippe S. Dartiguenave president on 12 August, and subsequently created the Gendarmerie d’Haïti, a constabulary led by U.S. marines.

Tennessee steamed to Philadelphia for repairs in dry dock, work that lasted through the end of the year 1915. The armored cruiser then returned to Haiti, where she served as flagship of a squadron off Port-au-Prince (28 January–24 February 1916). In March, she embarked a group of dignitaries at Hampton Roads for a two-month, round-trip cruise to Montevideo, returning to Hampton Roads on 4 May.

The Naval Act of 1916, President Woodrow Wilson’s request to build a navy equal to any other, included ten additional battleships, one of which (Battleship No. 43) was slated to be named Tennessee. Consequently, on 25 May, Tennessee was renamed Memphis, honoring the city in Tennessee, so that the name of the state could be reassigned to one of those new capital ships.

When a civil war erupted in the Dominican Republic in April 1916, local strongman Gen. Desiderio A. Álvarez staging a coup against President Juan I. J. Pereyra, artillery fire from one or both of the warring parties struck the U.S. Legation more than once. Consequently, U.S. Minister to the Dominican Republic William W. Russell, requested marines to land and protect the legation and Americans trapped by the fighting. Caperton dispatched the Sixth and Ninth Marine Companies (Capt. Frederick M. Wise, USMC, in command) on board transport Prairie from Haiti, who landed at Santo Domingo on 5 May. Castine (Gunboat No. 6) then landed 130 bluejackets to augment the marines, and additional reinforcements supplemented those men, compelling Álvarez to retreat from the city. The government forces failed to crush the rebellion, however, and U.S. marines and sailors fought sharp actions against the rebels.

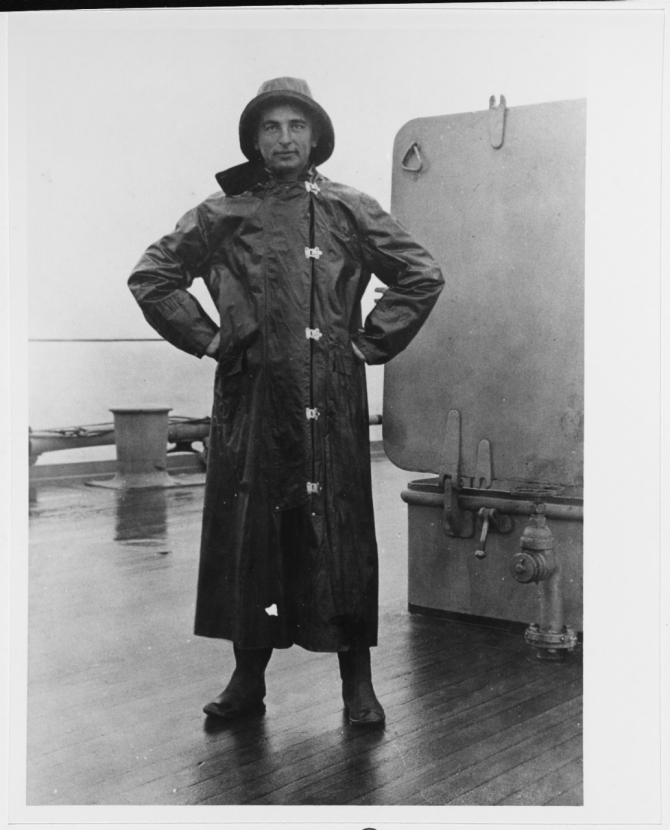

In July 1916, Memphis, Capt. Edward L. Beach in command, therefore got underway for the West Indies, arriving at Santo Domingo on 23 July for peace-keeping patrol off the rebellion-torn republic. Rear Adm. Charles F. Pond, who had relieved Caperton on 18 July, broke his flag in the armored cruiser.

During the afternoon watch on 29 August 1916, Memphis rode at anchor near Castine in the open roadstead off Santo Domingo. The sea was smooth, and the ship had not received any storm warnings. Capt. Beach and many of the ship’s company carried out their normal in-port routine, and Rear Adm. Pond and a liberty party were ashore.

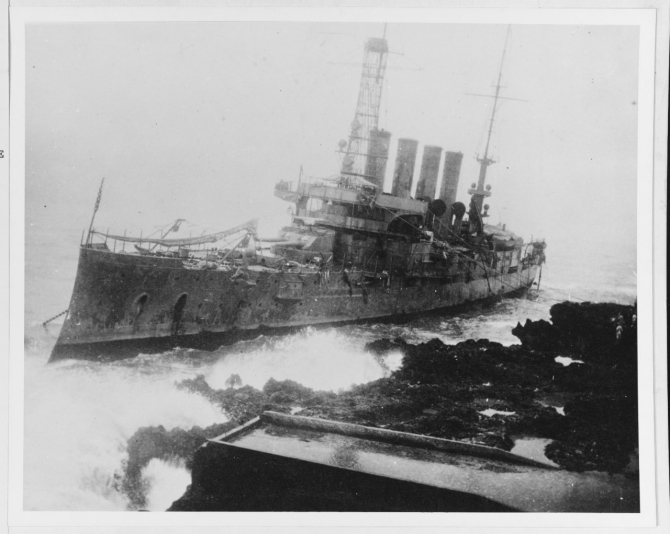

A seismic event within the depths of the Atlantic Ocean or Caribbean, however, triggered an apparent tsunami, or tidal wave, and the swells suddenly increased. Both ships began to roll noticeably. At about 1530, Capt. Beach ordered steam increased enough to allow the ship to leave the anchorage, previous experience having demonstrated that she could get up steam in about 40 minutes. Waves began breaking ashore, however, and Memphis rolled too much to recover her boats, so she sent two out to sea, soon to be followed by one of Castine’s. The swells grew in size and both ships began to prepare for heavy weather.

The heavy seas pounded Memphis and Castine, the ships’ violent rolling and pitching greatly hindering the laborious work. The waves rapidly mounted so steeply that they flowed over the armored cruiser’s decks and entered through ventilators, incompletely closed gun ports, and even her four tall smokestacks, impeding her crew’s efforts to raise steam and washing three men overboard. As a result, when the main tsunami reached the anchorage at about 1630, Memphis did not have enough steam available to run her engines properly. The waters smashed into the ship, reaching even the bridge and stacks, and lifting the ship by successive steps. Memphis dragged her anchor, all the while battering her keel and bottom against the roadstead’s floor, and at about 1700 she grounded on the rugged bottom in from 12 to 19 feet of water — and only 40 feet from precipitous rocky coastal cliffs.

A coral pinnacle crushed two of the boilers, bursting a steam pipe, and escaping steam scalded seven men to death in a fire room. In addition, 25 men drowned while on board small boats en route from the shore to the ship, including Fireman 1st Class Lawrence L. Crosier, in charge of one of the craft. A further five men died from two of the boats which put out to sea for safety when waves drove them ashore while they attempted to reach safety the following night. The total casualties numbered 43 dead and 204 injured. Sailors, marines, and local Dominicans hastily rigged shore lines and helped the ship’s remaining officers and men, many of them badly injured, reach shore. Castine, meanwhile, cleared the anchorage following a heroic effort that left her battered and barely seaworthy.

The embattled sailors fought heroically to save their ship and shipmates: three received the Medal of Honor. Lt. Claud A. Jones, the ship’s engineer officer, did everything possible to get the engines and boilers ready, and amidst clouds of scalding steam, thousands of tons of water pouring down upon him, and in almost complete darkness, Jones nobly remained at his station as long as the engines would turn over, exhibiting unselfish heroism which inspired the officers and men who were with him. When the boilers exploded, Jones and two sailors rushed into the fire room and drove the men there out, dragging some and carrying others to the engine room, where they could breathe fresh air again. Chief Machinist’s Mate George W. Rud bravely took his post in the engine room, but suffered serious burns in so doing, from which he immediately died, subsequently receiving the Medal of Honor posthumously. Machinist Charles H. Willey manned his position in the engineer’s department despite scalding steam and inrushing water, leaving only when ordered to do so. When the boilers exploded, Willey assisted in getting the men out of the fire room and carrying them into the engine room, saving some from almost certain death. All three men’s conduct went “above and beyond the call of duty.”

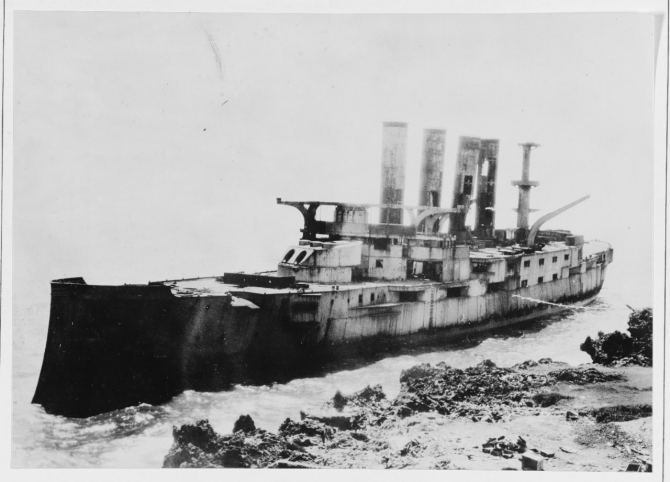

Naval and civilian experts soon carefully examined Memphis and determined that while it would have been possible to salvage the wreck, as a whole, they considered it impracticable because of the cost, and because delivering Memphis to a port with the facilities capable of repairing her would prove difficult and dangerous. The salvage, if successful, and repairs, if undertaken, would have taken two to three years and cost close to the value of the ship. In addition, the aging vessel was of a type no longer constructed by any naval power. All articles of a portable nature, whose value was commensurate with the cost of removal, were therefore recovered, and Memphis stricken from the Navy list on 17 December 1917.

The wreck remained just off Santo Domingo’s shoreline for many years, mute testimony to one of nature’s most powerful forces, until sold to A. H. Radetsky Iron & Metal Co., Denver, Colo., on 17 January 1922 for scrapping.

Mark L. Evans and Robert J. Cressman

29 August 2016

For additional material, including forecastle logs, artifacts, and memorabilia, see Tragedy of USS Memphis.