Kearsarge III (CV-33)

1946–1973

The third U.S. Navy ship named for the peak that rises in the White Mountains in Merrimack County, N.H.

III

(CV-33: displacement 30,800; length 888'; beam 93'; extreme width 136'; draft 30'8"; speed 33 knots; complement 2,100; armament 12 5-inch, 44 40-millimeter, 36 20-millimeter, 2 3-pounder (saluting); aircraft 90; class Essex)

The third Kearsarge (CV-33) was laid down on 1 March 1944 at Brooklyn, N.Y., by the New York Navy Yard; launched on 5 May 1945; sponsored by Mrs. Gwyneth C. Fitch, née Conger, wife of Vice Adm. Aubrey W. Fitch, Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (Air); and commissioned on 2 March 1946, Capt. Francis J. McKenna in command.

Kearsarge arrived at her homeport of Norfolk, Va., on 21 April 1946, and for the next year trained along the east coast. The ship cleared Norfolk on a midshipman training cruise into the North Atlantic that carried her to the United Kingdom and also into the Caribbean (7 June–11 August 1947). Kearsarge embarked Attack Carrier Air Group (CVAG) 3, consisting of 18 Grumman F8F-1 Bearcats of Fighting Squadron (VF) 4A, 24 Curtiss SB2C-5 Helldivers of Attack Squadron (VA) 3A, and nine Eastern TBM-3E, three TBM-3J, and a trio of TBM-3Q Avengers of VA-4A, along with a single North American SNJ-5C Texan and an SNJ-4. Upon the carrier’s return to the United States, she engaged in maneuvers for ten months.

As she prepared to deploy to the Mediterranean, however, a 50-foot open launch carrying 90 men back to the ship from liberty capsized in heavy surf off Hampton Roads, Va., on 31 May 1948. At 2000 Liberty Call expired and launches began to shuttle men from ashore to the anchored ship, but at about 2045 the pounding swells swamped the boat not far from the carrier. The Officer of the Deck sounded general quarters, and the signalmen used searchlights to illumine the exceptionally dark night. Few of the passengers wore life vests, and although many men bravely attempted to battle the swells and reach the ship’s gangway, the strong current swept some of them away. Rescuers saved 68 men from the tragedy, but altogether 18 sailors and ten marines died.

The ship’s company sadly loaded the aircraft and embarked men of Carrier Air Group (CVG) 3 and Kearsarge stood out of Hampton Roads for duty with the Sixth Fleet on 1 June 1948. During her tour in the Mediterranean the Sixth Fleet stood on alert to insure peace in the midst of the Arab-Israeli War. Kearsarge returned to Naval Air Station (NAS) Quonset Point, R.I., on 2 October. The Navy repeatedly experimented with new concepts and equipment and VA-174 tested new Martin AM-1 Maulers during carrier qualifications on board Kearsarge off Quonset Point later that year (27–28 December 1948). On 7 April 1949, an entourage of distinguished guests boarded Kearsarge and she carried them to sea to observe a Lockheed P2V-3C Neptune dramatically launch from large aircraft carrier Midway (CVB-41) via Jet Assisted Takeoff (JATO). The ship operated along the Atlantic Coast and the Caribbean until 27 January 1950, when she sailed for the west coast without any aircraft embarked. The carrier arrived at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard at Bremerton, Wash., on 23 February. On 16 June 1950, Kearsarge was decommissioned there for an SCB-27A modernization overhaul that would enable her to handle jet aircraft.

Kearsarge was recommissioned on 15 February 1952, Capt. Louis B. French in command. Following shakedown the carrier cleared San Diego on 11 August for intensive flight training off the Hawaiian Islands. Her readiness complete, she sailed for the Far East to engage in combat missions in the Korean War. The ship embarked Carrier Air Group (CVG) 101, comprising the McDonnell F2H-2 (F-2) Banshees of Fighter Squadron (VF) 11, Grumman F9F-2 (F-9) Panthers of VF-721, Vought F4U-4 Corsairs of VF-884, Douglas AD-4/L Skyraiders of VA-702, F2H-2Ps of Fleet Composite Squadron (VC) 61 Detachment F, F4U-5Ns of VC-3 Detachment F, AD-4Ws of VC-11 Detachment F, AD-4N (A-1D)s of VC-35 Detachment F, and a single Sikorsky HO3S-1 (H-5) of Helicopter Utility Squadron (HU) 1 Detachment 15.

Arriving at Naval Operating Base (NOB) Yokosuka, Japan, on 8 September 1952, Kearsarge conducted air refresher operations, twice refueled destroyer Kidd (DD-661), and at 2322 on the 16th joined the fast carrier Task Force 77 off the Korean east coast. Kearsarge summarized her deployment: “The assigned mission of this force, in support of the United Nations conflict with North Korea, was interdiction of supply and transportation facilities and close air support of United Nations troops.” She generally steamed with one to three other carriers: Bon Homme Richard (CV-31), with CVG-7 embarked, Essex (CV-9), with Air Task Group (ATG) 2, and Princeton (CV-37) and CVG-19. All four ships were reclassified to attack aircraft carriers (CVAs) on 1 October. Some of the other ships that screened and worked with the carriers at times included battleship Iowa (BB-61), heavy cruisers Helena (CA-75), Los Angeles (CA-135), and Toledo (CA-133), antiaircraft light cruiser Juneau (CLAA-119), and Frank E. Evans (DD-754), Hopewell (DD-681), and Harry E. Hubbard (DD-748). For the next five months Kearsarge’s aircraft flew nearly 6,000 sorties against communist forces in North Korea, unleashing airborne fury on enemy positions. The ship alternatively launched air raids, trained, especially in antiaircraft gunnery exercises and station keeping, and pulled off the line to refuel.

Kearsarge started her deployment by hurling a series of air strikes against the enemy, who fought back fiercely. Ground fire peppered a Skyraider’s after compartment during a raid on 17 September 1952, struck the plane’s radar scope and splattered metal and glass fragments through the compartment, fracturing the crewman’s skull in his left temporal bone. They recovered on board and x-rays revealed that some of the shards lodged around his left orbit. The man was evacuated for further treatment to Naval Hospital, Yokosuka. The following day a hung rocket broke loose from a Banshee and skidded along the flight deck and struck two men. The first one suffered a fracture of the left femur plus a compound comminuted fracture of the tibia and fibula, which necessitated the medical team amputating his left lower leg. The other man sustained a very severe compound comminuted fracture of the left tibia and fibula which required open reduction with bone plates and screws. Both of the men underwent the above treatment on board and were then also transferred to Yokosuka.

Rear Adm. Robert F. Hickey, Commander, Carrier Division (ComCarDiv) 5, broke his flag in Kearsarge as he relieved Rear Adm. Herbert E. Regan, ComCarDiv 1, who flew his flag in Bon Homme Richard in command of TF 77, on the 21st. On the 24th (0830–1253), 5 October (1110–1404), 8 October (0935–1041 and 1133–1259) helos brought Gen. Mark W. Clark, USA, Commander, UN Forces Far East, Vice Adm. Robert P. Briscoe, Commander, Naval Forces Far East, and Vice Adm. Joseph J. Clark, Commander, Seventh Fleet, from Iowa on board for a conference concerning operations. During this period planners hurled carrier aircraft against communist troops along the front lines in the Korean Peninsula that operated beyond the range of UN artillery. Naval aviators referred to these raids as “Cherokee strikes” in recognition of Clark’s Native American ancestry.

Foul weather sometimes compelled planners to cancel their air strikes and such occurred the following day on the 25th. The fighting continued, however, and Lt. (j.g.) John W. Shook, USNR, of VF-884 launched in an F4U-4 (BuNo 81277) from Kearsarge to strafe and bomb enemy troops near Sŏngjin [Kinchaek] in North Korea on 30 September. Shook flew a strafing run but his wingman observed him suddenly fall into an inverted dive and he crashed in the Corsair in the water not far from Sŏngjin from unknown causes. His wingman sadly reported that he did not see the pilot survive. The following day a helo again transported Adm. Clark from Iowa to Kearsarge for a conference. VF-884 marked another squadron loss when Lt. Eugene F. Johnson, USNR, took off in an F4U-4 Corsair (BuNo 80798), Side No. 412, and attacked enemy supply areas near Yongpo-ri, North Korea. Four Mikoyan-Gurevich (MiG) 15 Fagots pounced on Johnson and shot him down and he crashed in a steep dive into the water near the beach at Wŏnsan, North Korea. The UN forces besieged the North Korean port from the sea, and temporarily developed the area into a sanctuary for aircraft damaged by enemy fire that ditched in the harbor. Helicopters pulled the downed aircrew to safety and thereby saved men from death or imprisonment by the enemy, but in this instance could not rescue Johnson.

The enemy began an enormous artillery and mortar barrage against the UN forces along the front line as they launched a series of attacks on 6 October 1952. The communist offensive led to some of the heaviest fighting along the front in nearly a year. Much of the seesaw clashes centered on two key heights, Hills 281 and 395, northwest of Ch'ŏrwŏn-kun.

Lt. F. C. Anderson, USNR, and his crewman of VC-35 Detachment F launched in a Skyraider (BuNo 125712) but crashed into the water due to a catapult sling failure while taking off on 5 October. Rescuers recovered both men unharmed. A heavy pace of air operations to help the beleaguered allied troops on the ground inevitably led to further mishaps and on the 7th Ens. Lloyd F. Troutman, USNR, of VF-884 experienced a mechanical failure in his Corsair (BuNo 96769) and made a scorching wheels up landing on the flight deck. Lt. C. Q. Murphy, USNR, of VA-702 flew a bombing run in a Skyraider (BuNo 123993) over Yongpo-ri on that busy day. Enemy gunfire hit his plane, the engine caught fire and failed, and Murphy crashed into the water off Wŏnsan but men pulled the pilot from the sea uninjured.

On 8 October 1952, Kearsarge took part in the preliminary phases of Operation Decoy—a combined arms operation that included an amphibious demonstration aimed at Kojo (13–15 October). Allied planners including Vice Adm. Robert P. Briscoe, Commander, Naval Forces, Far East, intended to lure the enemy troops into exposing themselves to attack and destruction by U.S. forces. The stratagem did not include landing troops per se, but giving the illusion of doing so that the communists would rush reserves to the area to contain the apparent landings, only to face air strikes and naval gunfire. Decoy thus consisted of two phases, the first being a feint to draw in the enemy, and the second a series of raids to pound them.

A dozen F-2H2s launched from Kearsarge for Operation Red Cow, one of the work-up plans, on the 8th. The Banshees rendezvoused with ten USAF Boeing B-29s of the 98th Bomb Wing and escorted the Superfortresses on a daylight raid against the enemy rail center at Kowŏn, North Korea. The raid marked the second and final time that Navy jets escorted Air Force bombers into enemy airspace during the war.

In the meanwhile, Joint Amphibious TF 7, Rear Adm. Francis X. McInerney, orchestrated the complex maneuvers of Operation Wrangler, the amphibious feint. At times alerts went out to elements of the XVI Corps, the 40th and 45th Infantry Divisions, 1st Cavalry Division, and 118th Regimental Combat Team for their possible deployment to Decoy. Maj. Gen. Anthony Trudeau, USA, led the troops.

The task force formed for the diversionary phase centered on the Bombardment Group, TF 71.1, comprising Bombardment Element No. 1, TE 71.11, Helena and a pair of destroyers; Bombardment Element No. 2, TE 71.12, Toledo and two destroyers; and Bombardment Element No. 3, TE 71.13, Iowa and Frank E. Evans (DD-754); along with the Tactical Air Direction Group, TE 71.2; Beach Reconnaissance and Underwater Demolition Team Group, TE 71.3; Mine Warfare Group, TE 71.4; and the Screen Group, TE 71.5.

A helo carried Rear Adm. Walter G. Schindler, Commander, TF 77.1 and ComCarDiv 3, to Kearsarge for a planning meeting on the 10th (1130–1340). Heavy weather drove the ship to cancel her strikes on the morning of the 11th, and she sent only eight sorties that afternoon. The day nonetheless became a tragic one for the ship. While men parked her HO3S-1 on a flight deck edge elevator the helicopter’s rotor accidentally engaged and it tipped over. The whirling blades killed three men instantly, and a fourth died from his wounds two hours and 45 minutes later: Walter E. Bailey, Elmer C. Coon Jr., Harley E. Haigh, and Fernando Magri. The mishap also injured seven men on the ship’s flight deck, one of whom sustained eight fractured ribs with hem pneumothorax, bilateral facture of the pelvis and kidney, and kidney and bladder damage, while the other six incurred minor injuries, three of whom required prolonger in-patient care.

Kearsarge continued to operate at the heart of the carrier forces steaming offshore and a helo flew Adm. Arthur W. Radford, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet, Vice Adm. Briscoe, Vice Adm. Clark, and Rear Adm. John E. Gingrich, Commander, UN Blockade and Escort Force, TF 95, on board for a conference on the 12th (0839–1301). Another helo brought Rear Adm. Regan from Bon Homme Richard at 1130. The cross-decking meetings kept on and two days later at 0937 on the 14th Regan assumed tactical command of TF 77. Kearsarge’s HO3S-1 flew Rear Adm. Hickey over to Bon Homme Richard to confer with Regan (0940–1740). Hickey then resumed tactical command of the task force.

Mail issues delayed Frank E. Evans from receiving TF 76 Operation Plan 101(A)-52 in a timely manner, and so she protected Iowa from enemy submarines as they made for the area. The other bombardment ships pounded the enemy positions each day beginning on the 13th, but only on the following night did Iowa and Frank E. Evans finally reach the area. While the ships blasted the enemy soldiers around Kojo, the Americans encountered heavy surf as they rehearsed the landings at Kangnung [Gangneung-si] on South Korea’s east coast, which compelled them to cancel the training.

Attack Force, TF 76, formed to carry out Wrangler. The force comprised the Flagship Element, TE 76.00; Tactical Air Control Element, TE 76.01; Control Element, TE 76.02; Gunfire Support Group, TE 76.1. The latter numbered Fire Support Unit 1, TU 76.1.1, Iowa (the flagship), Toledo, Bausell (DD-845), and Frank E. Evans; Fire Support Unit 2, TU 76.1.2, Helena (flagship), O’Brien (DD-725), and Perkins (DD-877); and Fire Support Unit 3, TU 76.1.3, medium landing ships (rocket) LSM(R)-412 (flagship), LSM(R)-527, and LSM(R)-536. In addition, the Air Support Group, TU 76.2; Minesweeping Group, TU 76.3; Transport Group, TU 76.4; Fast Movement Group, TU 76.5; Screening Group, TU 76.6; and the Anti-Submarine Warfare Group, TU 76.7 rounded out the ships gathered for the endeavor.

Despite the overwhelming firepower arrayed against the communist troops they resolutely engaged the ships, and guns in the northern part of Area No. 13 shot at Frank E. Evans at least 10–15 times, their splashes rising uncomfortably close until the ship turned her own guns on the artillery and silenced them. Enemy shore batteries fired several rounds that narrowly missed Perkins, but killed one man and wounded 17 more. Concrete evidence concerning large scale enemy movements to counter the landings failed to materialize in the following days. Allied planners could not determine whether the lack of activity indicated communist mobility and command, control, communications, and intelligence difficulties, or resolve to await the outcome of the landings and strike at their advantage.

The bitter fighting for Hills 281 and 395 also partially shifted by the 15th when the enemy begrudgingly conceded UN possession of the crucial heights. Allied troops counted an estimated 2,000 Chinese dead in and around the battlefield as they enemy regrouped from the carnage. The Chinese People’s Volunteer Army’s XII and XV Corps undauntedly attacked a forested ridge they named Shangganling, which allied troops dubbed Triangle Hill, a prominence that rose just over a mile north of Gimhwa-eup on the 14th. The fighting raged into November and UN desperately relied upon air and artillery support.

Cmdr. Bruce T. Simonds, VA-702’s commanding officer, died when he crashed while taking off in a Skyraider (BuNo 123962) from the starboard catapult on 16 October 1952. Crewmen saw Simonds float free of the sinking plane along the port side of the ship, his life vest apparently inflated but his parachute still strapped to his chest. Helicopters and a destroyer rushed to the scene but inexplicably failed to locate any trace of the pilot. Investigators surmised that although the catapult otherwise appeared to function normally, a faulty bridle or plane catapult hook caused the bridle to come apart and the Skyraider fatally dropped over the bow. Two days later Regan relieved Hickey in tactical command of TF 77 and Kearsarge came about for NOB Yokosuka. The ship reached that port and completed a shipyard availability and a period of rest for her exhausted men (20–27 October).

The carrier evaluated the morale of the crew and embarked air group, including an average of 2,072 enlisted sailors and marines, as “excellent” during the first several weeks of the line period (14 September–20 October 1952), but noted that an increasing number of men exhibited signs of stress during the final two weeks. Kearsarge attempted to cope with the rigors of the war by a variety of means and showed an average of 21 motion pictures per week. Most of the ship’s company and her embarked air group looked forward to the films as a major form of recreation. In addition, they signed out a daily average of 40 books from the ship’s library, and also took advantage of the provided board games and playing cards. The ship’s office made daily press releases available, as well as a bi-weekly ship’s newspaper that discussed the events around Kearsarge as well as the world at large. Sailors also distributed a monthly average of 323 copies of magazines around the ship. The carrier opened a hobby shop on 1 October, and men built so many of the model airplanes, ships, and boats offered that the store sold out its entire stock in two weeks.

The stress of the Korean War and deployment far from home, however, also led the ship to increase her religious program to a total of 26 divine services held each week. These comprised three Catholic masses, three Protestant services, and a Latter Day Saints meeting each Sunday; Jewish services each Friday; observing Jewish high holidays including special services for New Year and Yom Kippur; a Protestant Bible study each Wednesday and a Latter Day Saints class every Thursday, and daily Catholic masses and Rosaries and Protestant meetings. Many men found spiritual comfort in their gatherings in the midst of the horror of war. Finally, the ship arranged to send 190 officers, principally pilots, and up to 40% of the enlisted men, to Rest and Recreation Camps.

As far as the air operations are concerned, Kearsarge recorded a total of 1,168 catapult shots, 614 aircraft launches from the port catapult and 554 from the starboard, and 2,132 flight deck landings for the line period. Aircraft crashed into the barrier four times, and 22 cross-deck pendants were replaced. Aircraft flew 77 aerial photographic sorties and shot a total of 135 reels of reconnaissance film, primarily target searches, route surveillance, and flak (antiaircraft artillery) studies, along with a limited number of damage assessments and call missions.

The ship’s company and the air group discovered that Skyraiders required a “long deck take off run” under “minimum wind conditions while carrying a large bomb load.” The flight deck handlers thus developed the habit of spotting the planes across the flight deck, and of loading the outward wing stubs before they placed them in the final respot position. They furthermore recommended that carriers that embarked Banshees should equip their tractors and tow-bars for towing aft. The men explained that sailors could accomplish the conversion by turning the towing lugs on the universal tow-bar 90°, and equipping the tractors with a padded “T” frame to keep the tail from injuring the driver. In addition, they counseled that handlers should two Panthers backward, especially under high wind conditions, and Kearsarge manufactured a two-bar for that purpose. The ship could not have controlled the embarked jets without her Mk 10 identification friend or foe (IFF), as the jets failed to show up on radars as often or not.

The ship began her line period with four starter jeeps and VC-11 brought a fifth, but two suffered mechanical issues at one point and their temporary loss seriously curtailed operations. Kearsarge sent a “speed letter” to Commander, Fleet Air Japan requesting two replacement starter jeeps, and reported that Banshees in particular took longer to start than Panthers and that a minimum of four vehicles sufficed to launch a strike package of 20 jets. Kearsarge experienced growing difficulty maintaining a watertight flight deck because of two main issues. Jet blast melted the marine glue and blew loose the oakum permitting water to work below the wooden deck. The more serious problem occurred because of the apparent thinness of the steel decking below the wood. Whenever the leakage on the 02 level overheard became serious enough to justify tearing out the glass insulation to stop leaks by welding, men observed that the wood deck securing studs were shot through or close enough to steel, that whenever heavy aircraft moved the deck the stress caused the studs to work and leaks developed. She underwent limited repairs to these issues at Yokosuka, but ultimately required more extensive work at a U.S. west coast shipyard.

Kearsarge’s Combat Information Center (CIC) experienced a mix of CIC, flag, and air control functions but exhibited fine teamwork because they developed a high degree of cooperation between the ship and flag officers, the type of watches employed for enlisted men, and the effective use of a Radar Control Officer. The enlisted men stood their daily CIC watches in three sections, two of them heavy with 24 men each, and one lighter with 14 men. One heavy section worked two watches (0300–0600 and 1200–1800), the other (0600–1200 and 1800–2100), and the light section (2100–0300). The watch bill worked smoothly by ensuring that the largest number of sailors manned their stations during the busiest flight hours, and that CIC maintained continuity of operations since the watches changed when the fewest aircraft launched or recovered, as well as conformed to meal times. The system meant long hours for the daytime watchstanders but they received a full night’s sleep. Radars and radios from other U.S. and allied ships, especially AN/SPS-6 air search (with limited surface search capability) radar and VHS radios, repeatedly interfered with the ship’s own radar and radios.

One or both of the winches experienced problems that impacted the ship loading ammunition on more than once occasion. The Engineering Force laboriously repaired them but their maintenance issues proved exasperating, especially when the forward winch went down because of blown gaskets on 14 October, and Kearsarge consequently incurred trouble as she attempted to load cargo nets from ammunition ship Paricutin (AE-18). The latter’s winch operator thus held the strain but the carrier’s winch operator hauled against the strain in order to raise the cargo nets high enough to clear the ship’s side. Although the crew eventually repaired the winches they observed that they operated slower than those of replenishment ships.

Kearsarge wrapped up the yard work and turned back to the fighting (28 October–1 November 1952). The ship sailed with 16 operational F2H-2s of VF-11, 15 F9F-2s of VF-721, 13 F4U-4s of VF-884, 16 AD-4/Ls of VA-702, three F2H-2Ps of VC-61 Detachment F, four F4U-5Ns of VC-3 Detachment F, four AD-4Ns of VC-35 Detachment F, three AD-4Ws of VC-11 Detachment F, and a single HO3S-1 of HU-1 Detachment 15.

The ship reached the war zone on the 1st of the month but heavy seas restricted her to launch only 42 sorties. Morning heckler flights attacked the enemy’s main supply routes north and west of Wŏnsan, damaging a locomotive and several rail cars. Panthers, Corsairs, and Skyraiders flew a coordinated strike to support allied soldiers fighting the communist troops along the front line. Lt. O. O. Glisson, USNR, of VF-721 flew one of the Panthers (BuNo 123586) but reported a rough running engine and turned for the Korean east coast. Observers last saw Glisson enter an overcast and his jet crashed about ten miles from the shoreline. Antiaircraft fire hit Lt. Richard G. Rider of VF-884 while he dived in his F4U-4 Corsair (BuNo 97255) on a target near Chun-Chon. Rider failed to recover from his dive.

The communist troops reinforced their front lines with antiaircraft guns throughout this period and the ship’s and air group’s planners unsuccessfully tried several tactics to suppress the flak until they developed a new plan. A division of jets would often precede the strike group into the target area by approximately 15–20 seconds and strafe from high altitude, and strafe and drop fragmentation bombs on gun positions identified by aerial reconnaissance. The remaining aircraft would wait until they sighted the all but inevitable flashes from the enemy guns and then push over in section attacks. In the event that the enemy gunners held their fire or the pilots could not spot them, they would then fly flanking runs. When Kearsarge sent smaller strike groups of eight planes or so, the flak suppressors would recover from their initial runs and tail in behind the last strike bomber to cover the propeller driven aircraft as they pulled up.

The following day the weather improved and Kearsarge hurled 93 sorties against the enemy. Morning hecklers hit trucks and supply buildings along the main supply routes north of Hamhŭng and Wŏnsan. Other bombers struck enemy soldiers fighting the UN troops at the front, and others directed naval gunfire spots in the vicinity of Wŏnsan. The hecklers savaged enemy trucks attempting to slip past them the next morning on the 4th and destroyed numerous trucks near Sŏngjin. Corsairs and Skyraiders attacked supplies and built-up areas behind the front line in the central sector as the ship sent 103 sorties into battle. She launched 102 sorties on the 5th, and morning hecklers pounced on multiple trucks and rail cars, and jets damaged bridges, rail cars, and railroads, while Corsairs and Skyraiders again helped the hard-pressed men at the front. Low ceiling and limited visibility restricted the ship to 63 sorties on the 6th, but jets destroyed or damaged a number of buildings holding enemy supplies. A Banshee (BuNo 125068) of VF-11 attempted to return to the ship but crashed the barrier and broke its port wing tip light.

Kearsarge launched 93 sorties on 8 November 1952. Propeller driven aircraft coordinated with the jets to hit enemy heavy artillery positions along the front line in the central sector, but pilots reported that they flew through the heaviest flak they had encountered in the war to date. Lt. Cmdr. F. W. Bowen, USNR, the commanding officer of VF-884, failed to recover from a dive in his F4U-4 (BuNo 97100) and analysts believed that enemy fire shot down his Corsair. Jets assailed supply areas south of Wŏnsan with what the ship reported as “excellent results,” and night hecklers destroyed trucks and damaged a small ship along the beach in the vicinity of Songjan-Man. Foul weather over the target area hampered operations on the 9th and the carrier only sent 20 sorties into the air. Corsairs and Skyraiders attacked troops and gun positions along the central front on 10 November, and jets destroyed a number of trucks and ox-carts traveling along the main supply route. Heavy weather to the north precluded planned strikes in those areas and aircraft flew 99 sorties from the ship. A weather front impacted operations over the following days but on the 15th Kearsarge sent 86 sorties against the communists. Planes and jets destroyed many ox-carts and a few trucks, supported troops at the front, and spotted naval gunfire salvoes along the coast.

Morning hecklers on the 16th diverted to fly Rescue Combat Air Patrol for a downed pilot, but most of the 100 sorties bombed and strafed enemy troops at the front and supply areas to the west of Wŏnsan. Kearsarge launched 98 sorties on 17 November 1952. Hecklers that flew early that morning scored hits on a number of trucks and made two rail cuts, while other aircraft roared in against communist troops in the Chonjin area, and still others spotted for ships as they fired at the enemy.

Kearsarge worked with Essex (CVA-9) and Oriskany (CVA-34) as they rotated their protective fighters through Combat Air Patrols (CAPs) on 18 November 1952, a day that dawned as any other but marked a swirling clash of dogfights. Corsairs and Skyraiders flying from Kearsarge assailed enemy troops in the Hoeryŏng area as the ship sent 43 sorties into the air. The day’s aerial mêlée meanwhile began for Kearsarge when she received a report of “bogies” (unidentified aircraft on the radar screen) reported at an altitude of 25,000 feet. Some of her strike aircraft flew against targets on the beach between Chonjin and the Soviet border on a course that could potentially render them vulnerable to the enemy fighters.

Kearsarge quickly vectored her CAP of four F2H-2 Banshees of VF-11 to the north at 30,000 to intercept the intruders. The jets flew a formation of sections spaced abeam at 600 feet, and with the wingmen four aircraft lengths to the outside of the section leaders, and well up on the beam. Flying the formation allowed maximum visual coverage of the opposite section, and the carrier reported that the tactics “paid large dividends” during the encounter.

As the Banshees headed toward their interceptions the pilots sighted a pair of MiG-15 Fagots at 12 o’clock down and a range of eight miles, flying a course paralleling the CAP’s vector. The Banshees flew at 0.82 mach and approached the Fagots relatively slowly, but when they closed to two miles the MiGs suddenly accelerated and attempted to move away rapidly. Kearsarge’s controller radioed the CAP to resume their protective flights over the ship and the jets swung around to their port. As the Banshees banked into their turn they spotted eight MiG-15s two o’clock up at eight miles. Some of the Americans involved suspected that the enemy flew the first two Fagots at lower altitude as bait in order to lure the patrol fighters into a trap. The Banshees maneuvered to keep the other eight enemy jets in sight for about five minutes, and then turned from the fray on a northwesterly heading.

The Banshees resumed a southerly sector for station but after flying that course for scarcely a minute, the leader sighted two MiGs making a run on the second section from five o’clock high. The second section flew to starboard of the lead section. The leader ordered the second section to stand by for a break to starboard, and then began a right turn to intercept the enemy jets. The communist pilots immediately broke off their attack to starboard before entering firing range, and climbed away from the Americans rapidly. The ship then ordered the Banshees to return on board. Throughout the incident the CAP jets managed to maintain an up-sun position, which gave them a marked visibility advantage. The pilots explained during their debriefing that the MiGs’ silver finish made sighting them at long range “quite easy under such sun conditions.”

The day proved to be a busy one as another group of Navy pilots flying F9F-5 Panthers of VF-781 from Oriskany tangled with seven enemy aircraft during the afternoon watch. Lt. E. Royce Williams and Lt. (j.g.) John D. Middleton of that squadron claimed to splash at least two of the MiG-15s and damage two more. Williams received the Silver Star for his “outstanding courage by placing himself and his accompanying planes between the Task Force and an attacking group of seven enemy MiG-15 aircraft, thereby protecting the Task Force from attack.” Williams aggressively closed and outmaneuvered the enemy pilots, at least one of whom also shot up Williams’ Panther No. 106 (BuNo 125459). Williams dodged into cloud cover and gamely “returned his almost uncontrollable aircraft on board” Oriskany, where maintainers subsequently repaired the damaged jet.

Middleton also received the Silver Star for “unhesitatingly” carrying out “daring firing runs on two enemy fighters. Attacking alone when mechanical difficulties forced his section leader [Lt. Claire R. Elwood experienced a fuel boost pump failure] to retire, he scored a hit on one jet plane, causing it to burn and spiral into the sea and, continuing his runs, succeeding in inflicting heavy damage upon a second hostile aircraft which immediately retired from further action.” Lt. (j.g.) David M. Rowlands, a pilot involved in the battle who flew as Williams’ wingman, received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Kearsarge hurled 97 sorties against the communist troops on 20 November 1952. Corsairs and Skyraiders flew close air support missions in direct support of UN soldiers locked in brutal combat with the enemy at the front in the central sector, principally the U.S. IX Corps and the South Korean II Corps against the Chinese XII, XV, and XXXVIII Corps. Jets and propeller driven aircraft suppressed flak batteries, and one group of jets bombed a lumber mill north of Hungnam with what the ship reported as “excellent results.” Night hecklers checked out one of the main supply routes north and west of Wŏnsan and discovered a convoy, which they promptly tore into and destroyed seven trucks.

The ship launched 94 sorties on the 21st, some of which spotted naval gunfire salvoes for the bombardment ships steaming off Wŏnsan, and jets and planes coordinated their strikes against communist antiaircraft artillery positions, bunkers, and entrenchments near the front line in the central sector. A strike group of Skyraiders savaged supply buildings west of Wŏnsan. Panthers roared in against a heavily defended highway bridge near Yangdŏk, but flak shot down Lt. Cmdr. Robert C. Hopping, VF-721’s executive officer, in his F9F-2 (BuNo 125145). Night hecklers retaliated when they reconnoitered coastal routes north of Wŏnsan and destroyed several trucks.

The unrelenting fighting continued the following day on 22 November as the ship launched 96 sorties. Corsairs and Skyraiders attempted to take the pressure off the troops locked in battle along the front line in the central and western sectors, and concentrated on blasting enemy antiaircraft guns. Other aircraft spotted for bombardment ships off Wŏnsan, and jets mauled communist trucks and ox-carts supplying their soldiers along the front. Night hecklers destroyed a locomotive and its train north of Hamhung, and (separately) ripped up a number of trucks in a convoy. Aircraft flew 95 sorties from Kearsarge’s flight deck on the 23rd, but a Panther’s (BuNo 127175) engine exploded upon taking off, though rescuers retrieved the pilot. Jets attacked supply nodes in the Pyŏngyang area. Corsairs and Skyraiders hit troop build-up and supply areas west of Wŏnsan in the vicinity of Majon'ni. Night hecklers damaged a locomotive and its train.

Foul weather impacted operations on 25 November and the carrier launched only 60 sorties. Morning hecklers attempted to break through the harsh weather to determine the extent of the front and in the process damaged several enemy trucks. Jets destroyed “numerous buildings” in the Hungnam area, and Corsairs and Skyraiders flew close air support for troops along the front’s central sector. The weather cleared the next day on the 26th and Kearsarge launched 101 sorties. Corsairs and Skyraiders bombed supply areas west of Wŏnsan, and jets and planes coordinated their runs against a supply area near Kilchu.

The weather seriously curtailed flight operations over the following fortnight, though a brief break on the 29th enabled Kearsarge to send 107 sorties into the war. Jets destroyed “numerous” ox-carts, and another strike hit a supply area north of Hamhung. One coordinated jet and propeller driven strike package flew into the teeth of flak over Pyŏngyang to bomb a supply area, Corsairs and Skyraiders supported troops at the front, and night hecklers damaged two locomotives and several trucks. A Skyraider (BuNo 123876) recovered from a bomb run when an antiaircraft shell apparently hit the plane’s propeller blade. The impact nearly severed the blade, and fragments penetrated the wrap cowling, cowl flaps, and wing spar. The pilot nonetheless survived and unscathed and bravely battled to keep his aircraft airborne for nearly 15 minutes until he could locate and land at K-18, an emergency divert airfield ashore. Maintainers counted 105 holes in the Skyraider but determined that the armor plate saved the man from injury and the plane itself, and thus justified the added weight. Another Skyraider (BuNo 123964) crashed the barrier when it returned to the ship, damaging its engine and propeller, as well as the port light and port wing. Morning hecklers destroyed a locomotive, three railroad cars, and eight trucks on the ship’s final day on the line on 4 December as she came about that morning at 0948 for NOB Yokosuka.

Kearsarge’s planners evaluated their success following the line period and noted that their new habit of sending the morning hecklers aloft for predawn raids succeeded in surprising the enemy on a number of occasions and led to finding and destroying more rolling stock. In addition to the losses already listed antiaircraft fire damaged in varying degrees 22 aircraft that flew from the ship during this line period. An unusual accident occurred when a .50 caliber incendiary round exploded in a Corsair’s blast tube and damaged the plane’s wing. Perplexed maintainers examined the aircraft and surmised that a hot barrel or a faulty projectile triggered the explosion, and the muzzle blast caused rivets in a large area of the wing to pop out. A potentially devastating problem affected the Mk. 55 Mod. 1 bomb racks on F4U-5Ns and F9F-2s. On two separate occasions the racks failed to latch properly and a bomb on each of the two aircraft jiggled loose and fell from the racks as the aircraft took off.

Kearsarge accomplished voyage repairs and upkeep at NOB Yokosuka and then steamed to the war zone (16–18 December 1952). The carrier replaced her losses and thus embarked 16 operational F2H-2s of VF-11, 15 F9F-2s of VF-721, 13 F4U-4s of VF-884, 16 AD-4/Ls of VA-702, three F2H-2Ps of VC-61 Detachment F, four F4U-5Ns of VC-3 Detachment F, four AD-4Ns of VC-35 Detachment F, three AD-4Ws of VC-11 Detachment F, and one HO3S-1 of HU-1 Detachment 15. Pilots flew 44 refresher sorties from the ship as she charted a course toward the fighting on the 17th.

Aircraft flew 58 sorties from Kearsarge as she returned to the Korean War on 18 December 1952. Jets attacked enemy supply routes near Wŏnsan, and jet and propeller driven aircraft coordinated their assault against supply areas behind the central sector of the front. The ship pulled off the line to replenish on the 19th, and continued that routine during her deployment so that she did not launch sorties every day, though she and the other carriers took turns relieving each other to accomplish their refueling and reprovisioning. On the 20th some 104 sorties from the ship struck supply and billeting areas west of Wŏnsan, and savaged trucks, ox-carts, and buildings along the main supply routes. Other aircraft spotted for ships that hurled their salvoes against enemy troops, and night hecklers destroyed eight trucks they detected attempting to slip down the coastal road north of Wŏnsan.

Kearsarge launched 90 sorties on the 21st. Corsairs and Skyraiders hit enemy supply areas along the front lines in the western sector, and jets flew flak suppression runs during these missions. Other aircraft spotted for ship’s as they unleashed their salvoes while steaming along the Korean east coast. Pilots reported that they destroyed or damaged “numerous” trucks, and monitored a reported sighting of MiGs flying north and west of Wŏnsan later in the day, though the communist jets did not attack. Propeller driven aircraft attacked enemy supply areas north of Pukchong, North Korea, the following day. Jets struck the main supply routes and both series of strikes destroyed trucks and ox-carts. Night hecklers destroyed a number of trucks and buildings when they assailed the supply lines north and west of Wŏnsan. The ship launched a total of 97 sorties. Kearsarge sent 103 sorties against the enemy two days before Christmas on 23 December. Aircraft spotted for bombardment ships’ naval gunfire support off Wŏnsan, and Corsairs and Skyraiders bombed supply nodes in the Hungnam area. Jets covered the main supply routes and pilots on all the raids claimed to destroy a number of trucks and ox-carts. Night hecklers bombed and shot up seven trucks north and west of Wŏnsan.

Following an all too brief respite on Christmas Eve to replenish, the ship sadly marked the holiday itself by launching 44 sorties. Jets made multiple rail-cuts along the main supply routes in the central sector, and planes hit a railroad marshalling yard and supply areas north of Hongwŏn, North Korea. Ninety-nine sorties flew off Kearsarge’s flight deck on 26 December 1952. Morning heckler pilots attacked railroads along the coastal area north of Wŏnsan but did not spot locomotives or rolling stock. Other aircraft flew close air support runs for soldiers along the central and western sectors of the front lines, and Corsairs and Skyraiders mauled supply areas behind the front. Pilots on multiple instances throughout the day claimed to destroy trucks and ox-carts. Aircraft also spotted for ships’ gunners.

Morning heckler pilots discovered and destroyed a train north of Wŏnsan, and also knocked out a number of trucks on the 27th. A Corsair (BuNo 80996) of VF-884 suffered engine failure, most likely from a hit by antiaircraft fire, and ditched though the pilot survived. The 97 CVG-101 sorties that day furthermore included Skyraiders that savaged a supply area west of the vital port, jets that bombed trucks and ox-carts as they attempted to supply the communist troops at the front, a strike against supply areas north of Hamhung, and missions to spot naval gunfire. Kearsarge launched 100 sorties on 28 December, which included close air support of allied troops along the central sector of the front. A Panther (BuNo 123636) of VF-721 suffered a flame out and the pilot ditched but rescuers retrieved him before he fell into enemy hands. Corsairs and Skyraiders attacked the main enemy supply routes behind the eastern sector, jets struck the northern sector, and aircraft sighted targets for the bombardment group that steamed off Wŏnsan.

Lt. James E. Lee of VF-11 in his Banshee (BuNo 125060) attacked camouflaged enemy supply buildings east of Majon-ni near Yangdŏk, North Korea, on the 30th. Eyewitnesses saw Lee’s jet crash in the target area and burn, most likely hit by antiaircraft fire. Searchers could not reach Lee in time and he was reported missing. Corsairs and Skyraiders hit supply and billeting areas in the vicinity of Unggi [Sonbong], North Korea. Some of their targets lay along the North Korean border and provided an example of the tactical flexibility that Kearsarge offered the UN forces. Jets flew CAP and pounded the main supply routes north of Sŏngjin and in the southern sector. Other aircraft spotted for ships’ gunners that shot into enemy forces near Chongjin in a total of 101 sorties flown from the carrier. Propeller driven aircraft flew close air support runs for troops along the front’s central sector on New Year’s Eve 1952, jets attacked the enemy’s main supply routes behind the front lines, and aircraft spotted naval gunfire at Wŏnsan during the day’s 84 sorties.

Corsairs and Skyraiders kicked off the New Year on 2 January 1953, when they flew some of the ship’s 66 sorties in support of front line troops in the eastern sector. Jets flew a special strike against enemy troops and their lines of communication in the vicinity of Hachon, North Korea. Jets flying from Kearsarge destroyed a number of rail cars and ox-carts. The following day the carrier launched 83 sorties into the fray, and Corsairs and Skyraiders flew flak suppression and close air support runs for UN troops along the front in the western sector. Jets also tore into the main supply routes north and west of Wŏnsan and destroyed or damaged multiple trucks, ox-carts, and supply buildings. Other aircraft spotted for bombardment ships in the Wŏnsan area, and night hecklers surprised and knocked out a number of trucks along the coastal areas and west of the port. Kearsarge swung around the following day on 4 January and steamed to Hong Kong for a much needed port visit, where she moored to Buoy No. 1 (8–16 January). Some 334 men took tours, and a troupe of Chinese entertainers staged a show on board for two nights that the crew thoroughly enjoyed.

In addition to the aircraft the ship lost during the line period, enemy antiaircraft fire damaged 14 more. Pilots and maintainers agreed that their aircraft machine guns performed better than during the previous line period, partially because they devoted time to servicing them while the ship lay at Yokosuka between line periods, and partially because she fought for a shorter time. Aircraft did not launch with many rockets, but some returned with hung rockets because their motors turned out to be duds, or in the case of Corsairs their flying brass while making firing runs cut the weapons’ pigtails. About 75% of the hung bombs occurred because of electrical failures outside the bomb racks.

De Haven (DD-727) and Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729) escorted Kearsarge as she finished the liberty call in the British Crown Colony and steamed back to the fighting, often launching refresher sorties en route (16–29 January 1953). Rear Adm. Hickey, ComCarDiv-5, broke his flag in the ship as the senior officer present afloat. Kearsarge and CVG-101 embarked 15 operational F2H-2s of VF-11, 13 F9F-2s of VF-721, 12 F4U-4s of VF-884, 15 AD-4/Ls of VA-702, three F2H-2Ps of VC-61 Detachment F, three F4U-5Ns of VC-3 Detachment F, three AD-4Ns of VC-35 Detachment F, three AD-4Ws of VC-11 Detachment F, and one HO3S-1 of HU-1 Detachment 15. VF-721, VF-884, and VA-702 became VF-141, VF-144, and VA-145, respectively, on 4 February 1953.

Hickey dismissed De Haven and Lyman K. Swenson on the 17th and the pair detached for additional operations. The seasoned aircraft carrier continued on her way independently until Laws (DD-558) rendezvoused with her on the 19th and they steamed back into the war together. At 1625 the following day they rejoined TF 77 and Rear Adm. Apollo Soucek, ComCarDiv-3, hoisted his flag in command of the task force. Kearsarge reported that she worked with two other “heavies” as she turned into formation with Oriskany and Valley Forge (CVA-45).

CVG-101, which was redesignated CVG-14 on 4 February 1953, defined its primary mission during the ensuing line period as “to fly close air support of ground troops, destruction of enemy military supplies in the North Eastern half of Korea, interdiction of enemy main supply routes, destruction of enemy vehicles and ground troops, air support of NGF [naval gunfire support], and support of East Coast Blockade and Escort Force. Photographic and weather flights were employed in support of these missions as required.”

Morning hecklers initiated the 87 sorties that flew from the ship’s flight deck on 21 January 1953, as they prowled unsuccessfully for enemy vehicles or troops along the coastal areas north of Wŏnsan. Corsairs and Skyraiders followed them aloft and bombed a supply area located in that war-torn port and another about ten miles northeast of Kumsong. Aircraft flew close air support missions for the troops entrenched along the front’s eastern sector, and jets suppressed antiaircraft guns and attacked troop shelters at Majon-ni and Wŏnsan. A group of jets hit a mining area located 15 miles northeast of Yangdŏk. Los Angeles also joined the task force.

Kearsarge launched 81 sorties the following day. A Panther accidentally discharged a single round of 20 millimeter ammunition as the jet made a normal landing but the round struck and killed AB3 Kay S. Platt, a plane director, as he worked on the flight deck. Morning hecklers damaged a locomotive they discovered as they tore into the rail lines east and north of Wŏnsan. Jets suppressed flak batteries for propeller driven planes that attacked the main supply routes east and south of the port, and Corsairs and Skyraiders flew close air support missions for the troops locked in combat along the front line’s western and eastern sectors. Another strike group hit a supply and build-up area as the enemy prepared to renew their assault in the vicinity of the front’s eastern sector. A strike package of jets bombed a supply area near Kumdong-ni.

Aircraft flew 101 sorties from the ship’s flight deck on 23 January 1953. Morning hecklers destroyed a locomotive and a number of trucks along the main supply routes north and west of Wŏnsan. Antiaircraft fire apparently hit Cmdr. Denny P. Phillips, VF-11’s commanding officer, when he flew a reconnaissance mission in his F2H-2 Banshee (BuNo 125668). Phillips spotted some enemy troops and dived on them but the gunfire hit his jet and did not recover from the dive, about five miles west of Wŏnsan near 29°16'N, 127°15'E. Phillips was well liked and his loss dealt a heavy blow to VF-11, but Lt. Cmdr. Lawrence E. Flint assumed command of the squadron. Other aircraft furnished aerial spotting for the ships firing at the enemy from off that port. Corsairs and Skyraiders flew in direct support of UN soldiers fighting along the front’s central and eastern sectors. Other propeller driven planes assailed communist supply areas in the vicinity of Kock-a-ri, Nowam-ni, Obok-tong, and Paktal. One jet strike attacked a supply area near Kanbalgo-ri. A Banshee slammed into the barricade while returning from a raid. The jet careened into the barrier at 70 knots and one of the barrier cables sheared off the port landing gear mere moments before the Banshee hit the barricade. Eight engaging straps contacted the port wing and ten the starboard wing, and the purchase cable ran out nearly 60 feet. The impact severely damaged the jet but the pilot emerged from the crash unharmed. Los Angeles detached from the task force when the ships pulled off the line and replenished on the 24th.

Missouri (BB-63) briefly joined the task force for a few hours on the 25th as 95 sorties hurtled aloft from Kearsarge. Corsairs and Skyraiders attacked enemy supply build-up areas in the vicinity of Chaech-on-ai, Obok-tong, and Wŏnsan. Aircraft supported troops along the front’s central and eastern sectors, and jets acted as flak suppressors for planes. Jets furthermore struck the main supply routes north of Wŏnsan and supply areas near Haksongchon and Songinyong-ni. Night hecklers destroyed two trucks they detected along the coast north of Wŏnsan.

Kearsarge launched 101 sorties on 26 January 1953. Jets hunted for their prey along the main supply routes north and west of Wŏnsan, and propeller driven aircraft flew close air support for allied troops along the front lines in the central and western sectors. Other aircraft struck supply areas in the locality of Hwagye-ri, Sagiri, and Sosang-ni. Pilots claimed that they achieved “excellent results” in a strike against supply build-up areas in the vicinity of Pukchong. Night troublemakers attacked the communist coastal supply routes north of Wŏnsan.

Propeller driven aircraft flew close air support for UN soldiers along the front lines in the western and central sectors as part of the air group’s 98 sorties on the 27th. Aircraft spotted for ships while they shot at the communist troops from off Chongjin, and jets tackled the main supply routes north and west of Wŏnsan. The ship’s strikes hit barracks at Anhung-ni and Hungnam, and supply nodes in the vicinity of Masing-Nyong, Pujon-gang Reservoir, and Pyong-ni. Night hecklers destroyed and damaged a number of trucks north and west of Wŏnsan. Los Angeles rejoined the task force and Toledo briefly steamed with the ships before swinging around for other operations, though not before helicopter UP-30 lifted off from Kearsarge and transferred to the latter cruiser.

Foul weather hampered operations on and the ship only launched 61 sorties on 28 January. Jets suppressed flak and covered propeller driven aircraft that bombed supply areas near Pyongbugun, and other aircraft covered the main supply routes north and west of Wŏnsan. Night hecklers searched for enemy infiltrators along the coastal routes north and south of the port. Lt. Francis C. Anderson, USNR, and AT3 John R. Schmid of VC-35 Detachment F flew an AD-4N Skyraider (BuNo 124748) on one of the night heckler flights but failed to return. Searchers reported the two men’s last known position as crossing the beach outbound on a heading for the ship, and but a search and rescue mission could not find Anderson and Schmid and they were consequently listed as missing, cause unknown. Rochester (CA-124) joined the task force.

The rough weather also interfered with Kearsarge’s replenishment the following day, and although the ship received fuel oil and aviation gasoline she did not load ammunition, a vexing problem as she faced battle. Vice Adm. Clark gamely boarded a helo on Missouri and it flew him over to Kearsarge for a conference. A Skyraider then flew him ashore to K-16 airfield for an additional high level meeting. The plane returned Clark to Kearsarge, from which deck a help returned the busy admiral to the battleship.

On the 30th Kearsarge returned to the line and resumed launching strikes but only sent 42 sorties into the air because of the ongoing inclement weather. Jets nevertheless pounded enemy antiaircraft guns as Corsairs and Skyraiders attacked supply areas in Wŏnsan, and other jets searched for enemy vehicles and troops along the main supply routes north and west of the port. Missouri and Rochester (separately) detached from the task force for other duties.

Kearsarge launched 91 sorties on the final day of the month and morning hecklers covered the coastal routes north and west of Sŏngjin and Wŏnsan. Aircraft spotted naval gunfire salvoes for the bombardment group off the latter city, where Corsairs and Skyraiders also hit supply and billeting areas. Jet’s furthermore attacked military traffic in the northern sectors north of Wŏnsan. Strikes lacerated enemy supply areas at Haosang, Samho, and Tonghung-dong, as well as a billeting area at Wŏnsan. Philippine Sea (CVA-47) joined the task force.

Morning hecklers inaugurated the air group’s strikes on the 1st of the month for February 1953, by seeking the enemy along the main supply routes north and west of Wŏnsan. The first of 90 sorties that day, a strike package of Corsairs and Skyraiders followed that furnished close air support for the troops along the front line’s western and central sectors. Other aircraft bombed supply areas near Pyong-ni, or spotted naval gunfire shoots at Hunghan. Jets bombed supply nodes and stockpiles at Chukkun-ni, Taemok, Tokso-dong, and Yongung-ni.

Aircraft flew 94 sorties from Kearsarge on 2 February. Morning harassment flights damaged a locomotive while they covered the main supply routes north and west of Wŏnsan. Corsairs and Skyraiders pounded the enemy soldiers along the front line’s central and western sectors. Jets protected aircraft that struck supply areas at Pangokch-on and Pungsan. Strikes also targeted logistics areas at Sinpo, Songdong, and Tongyang, and troop and billeting zones in the vicinity of Somy-on and Tanchon. Rochester briefly steamed with TF 77, and Toledo did so the following day as the ships replenished.

Foul weather imposed delays throughout the 4th but the ship’s company and air group persevered and sent 91 sorties into the air. Morning jet and propeller driven aircraft packages struck supply areas in the Hamhung area. Aircraft supported troops along the front in the central sector, and raids assaulted logistics nodes at Hungnam and Kilchu. One division of planes bombed supply and billeting areas near Pokchong. The winter weather halted flight operations the following day on the 5th and the ship only launched two sorties. She sent a single strike group of 35 sorties to attack targets in the Hamhung-Hungnam area on the 6th, and the next day only a trio of sorties took off from the flight deck.

Antiaircraft fire shot down Lt. (j.g.) Donald H. Hagge of VA-145 in his AD-4 Skyraider (BuNo (123871) while he flew a “Cherokee” strike against an enemy supply area near Kuhaksan, 38°23'N, 129°49'E, on 8 February 1953. Hagge failed to return from the raid and although some of the other men in the flight believed they saw his parachute stream from the plane, he apparently did not escape the aircraft in time. The other 91 sorties flown from the ship that day included morning hecklers that destroyed or damaged “numerous” trucks along the main supply routes north and west of Wŏnsan. A division bombed a troop shelter at Soksadong-ni, and Corsairs and Skyraiders supported allied soldiers along the front line’s central sector.

Kearsarge launched another 92 sorties on the 9th and morning heckler destroyed “a few” trucks on the coastal routes north of the embattled port of Wŏnsan. Jets attacked targets on the main supply routes in the northern sectors, and troop and supply shelters at Pukchong and Sambong. Corsairs and Skyraiders flew close air support for frontline soldiers in the eastern sector. A strike also tore into supply buildings at Hungnam and Wapori.

Morning hecklers initiated the 105 sorties on 10 February 1953 when they knocked out or damaged a number of trucks on the coastal supply routes north of Wŏnsan. Propeller-driven aircraft hit supply areas north of Chongjin, and jets struck logistics areas in the vicinity of Hoerhong, Komusan, and Purongdong. On the 12th the carrier directed all of the strike aircraft of her 95 sorties against supply and billeting areas in the vicinity of Wŏnsan. Toledo departed from the task force but Los Angeles rejoined the formation.

Kearsarge sent the enemy a powerful Valentine’s Day warning when she launched no less than 113 sorties into the war on 14 February 1953. Lt. John R. Ralston of VF-141 made the ship’s 30,000th landing in his F9F-2. Meanwhile, jets suppressed flak for Corsairs and Skyraiders, and other jets hit supply areas south of Majon-ni and in the Wŏnsan area. Propeller driven aircraft supported troops along the front line’s eastern sector, and air strikes bombarded supply areas in the vicinity of Changjon and Yongdang-ni. Night heckles covered the coastal routes north of Wŏnsan.

One hundred six sorties flew off the ship on the 16th and morning hecklers destroyed or damaged a number of trucks they discovered along the coast north of Wŏnsan. Jets fulfilled the dangerous role of suppressing flak batteries so that propeller driven aircraft could accomplish their deadly work. One strike hit a supply area west of Majon-ni. Propeller-driven planes flew in direct support of troops along the front’s eastern sector, and other aircraft bombed logistics areas northwest of Muchon and in the vicinity of Taejong-ni.

Kearsarge launched 109 sorties on 17 February including forays by morning hecklers along the main supply routes south of Wŏnsan and the coastal routes north of Hamhung, savaging a number of trucks. Aircraft struck enemy supplies in the Hungnam area and east of Yangdŏk, and Corsairs and Skyraiders bombed supply areas north of Kilchu and in the Wŏnsan area.

Morning hecklers kicked off the 109 sorties on the 18th as they destroyed a locomotive and rail cars on the rail lines along the coast north of Wŏnsan. Jets and planes concentrated their efforts on interdicting railroads and bombing key rail bridges between Puchong and Wŏnsan.

The ship launched 110 sorties on the 20th that began with morning hecklers destroying a locomotive and many box cars on a railroad in the vicinity of Tanchon, and scoured rail lines along the coast north of Wŏnsan for more victims. Other aircraft spotted naval gunfire for the bombardment group off the strategic port of Wŏnsan, and Corsairs and Skyraiders flew close air support for troops along the front line’s central sector. Other strikes hit supply areas south of Andori and near Chang-jin. Jets covered the main supply routes west and north of Wŏnsan. One raid attacked enemy soldiers, supplies, and build-up areas near Kosong.

Despite foul weather Kearsarge launched 47 sorties on 21 February, led by morning hecklers that attacked railroads along the coast north and south of Wŏnsan. Jets and planes bombed rail lines north of Songjin.

A helicopter flew Vice Adm. Clark from Missouri to Kearsarge during the forenoon watch on 22 February 1953. Clark presented awards to men of the ship’s company and the air group, and that afternoon the helo returned the admiral to his flagship. Kidd shepherded Kearsarge as the carrier came about from the Korean War at 1212 and steamed toward Japanese waters. The following morning the ship launched nine jets and 26 propeller driven aircraft to NAS Atsugi, Japan. She refueled Kidd that afternoon and the destroyer then detached and the carrier proceeded independently. Kearsarge completed voyage repairs and upkeep at Yokosuka (25–28 February), turned over to Princeton, and at 1611 on the 28th charted a course for the United States, returning to her home-port of San Diego on 17 March.

“Morale of the officers and men of the Air Group created no serious problems during the entire combat tour,” CVG-14 reported. “The fatigue of long strenuous hours became quite noticeable after a four week period on the line. From 14 September 1952 to 25 February 1953, this Air Group spent two eight (8) day and one 10 day periods in port. However, the results obtained by this Air Group at all times speak for themselves.”

The group further added a cautionary note to their otherwise proud assessment: “During winter months a three (3) week tour on the line should be the maximum under a heavy operating schedule…Extensions of tours should be avoided if at all possible.”

The average on board count of enlisted men numbered 2,015 sailors and 60 marines, and the ship transferred 23 Navy enlisted men and received 52. “In spite of increasing fatigue among members of the crew,” the ship reported, “disciplinary cases did not increase appreciably during this period.” Antiaircraft fire damaged 22 aircraft that flew from the ship during the line period, and 16 of the 846 sorties aborted for one reason or another. While the ship fought in the Korean War during the deployment (16 September 1952–22 February 1953), aircraft flew 7,081 sorties (including 148 refresher) from the carrier, 104 of which aborted. The ship reported a “high” usage of aircraft engines on the deployment, another indicator of the fast-paced tempo. Kearsarge refueled destroyers 36 times, ten of them at night, and also at times transferred 56 passengers plus freight and mail a number of times.

Kearsarge sailed again for the Far East, this time with CVG-11, on 1 July 1953. The ship operated with the Seventh Fleet’s fast carrier force during the uneasy Korean War truce, and also kept watch over the Formosa [Taiwan] Strait to prevent the communists from interfering with the Chinese Nationalists on Taiwan. Kearsarge and her air group returned to San Diego on 18 January 1954, to resume training operations off California.

While Kearsarge trained in home waters later that year she took part in the film adaptation of James Michener’s Korean War novel The Bridges at Toko-Ri. Escort aircraft carrier Savo Island (CVE-78), a carrier in the story, was decommissioned following World War II on 12 December 1946. Savo Island never returned to active service so Oriskany stood in for her during most of the shooting. Oriskany required an overhaul, however, and Kearsarge briefly relieved her for some of the exterior sequences. Sailors painted over her identification number of 33 to 34 in order to maintain the continuity of the previous shots involving Oriskany.

Kearsarge also took part in the filming of the motion picture The Caine Mutiny in the San Diego area in 1954. Fleet Adm. William F. Halsey Jr., flies his flag in the carrier, a point of which the crew exhibited considerable pride, despite the fact that the ship was not commissioned until after World War II ended, and that Halsey generally led his fleet from New Jersey (BB-62) in the latter part of the war. Richard B. Anderson (DD-786) also appears in the film.

Clearing San Diego on 7 October 1954, Kearsarge, with CVG-11 again embarked, steamed toward her third deployment to the Far East. The communist Chinese triggered the First Taiwan Strait Crisis when they assaulted and captured the Yijiangshan Islands, which rise not far from the Chinese mainland, from the Nationalists (18–20 January 1955). The Nationalists had held the islands ever since the communists drove them from the mainland in 1949, and their loss led Congress to pass the Formosa Resolution, a joint resolution that President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed on 29 January, which attempted to keep the two Chinas from lunging at each other, and which enabled President Eisenhower to deploy U.S. forces to help the Nationalists defend themselves if necessary. In addition, the Americans and Nationalists agreed to Operation Pullback—to evacuate the Nationalists from the Tachen [Dachen] Islands, which are located near the Chinese coast off Taizhou in Chekiang [Zhejiang].

Essex, Kearsarge, Midway (CVB-41), Wasp (CV-18), and Yorktown (CV-10) formed a powerful carrier task force that covered the evacuations. The Seventh Fleet, Vice Adm. Alfred M. Pride, used 132 vessels and nearly 400 aircraft to evacuate approximately 10,000 Nationalist regulars and 4,000 guerilla fighters, along with 14,500 civilians (6–13 February 1955). On 9 February the only U.S. casualty occurred when Chinese antiaircraft fire damaged a Douglas AD-5W (EA-1E) of VC-11, Detachment H, while it flew an antisubmarine patrol from Wasp and apparently (unintentionally) overflew Chinese territory. The Skyraider ditched after sustaining damage, and Nationalist Chinese patrol boats rescued the three-man crew. Following the evacuation the communists landed and occupied the abandoned islands. Her cruise ended at San Diego on 12 May 1955.

Kearsarge operated for the next several years on the annual deployment schedule to the Far East and training operations off California. The ship and CVG-5 deployed to the Western Pacific (29 October 1955–17 May 1956). Kearsarge in the meantime underwent substantial improvements in the form of the SCB-125 program. She turned westward again, this time with ATG-3 on board, for another round of patrols and port visits across the Western Pacific (9 August 1957–2 April 1958). The group’s aircraft included the North American AJ-2 (A-2B) Savages of Heavy Attack Squadron (VAH) 16 Detachment J, and the Grumman F9F-8P (RF-9F) Cougars of Light Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron (VFP) 61 Detachment J.

The ship was fitted out as an antisubmarine warfare support carrier during the summer of 1958, a role for which she was reclassified to CVS-33 on 1 October 1958. Following intensive training in her new task, the carrier sailed for Seventh Fleet operations in the Far East on 5 September 1959. Kearsarge embarked the Grumman S2F-1 (S-2A) Trackers of Carrier Air Antisubmarine Squadron (VS) 21, a dozen Sikorsky HSS-1 (SH-34G) Seabats and four HSS-1Ns (SH-34J) of Helicopter Antisubmarine Squadron (HS) 6, and the AD-5Q (EA-1F) Skyraiders of Airborne Early Warning Squadron (VAW) 13 Detachment A.

Typhoon Vera grew into a powerful tempest that devastated the Japanese home islands in the last two weeks of September 1959. Storm surges swamped vessels and overwhelmed seawalls and levees, landslides swept over communities, and multiple buildings collapsed, crushing or trapping the people within. Vera killed and injured tens of thousands of people and rendered more than a million homeless. Kearsarge entered the port of Nagoya in the wake of the typhoon and supported relief operations (29 September–6 October). Her aircraft landed parties of medical staff and supplies, while her crew and air group donated clothing and money to the distressed people. These endeavors included evacuating almost 6,000 persons, delivering 200,000-pounds of relief cargo, and administering more than 17,000 typhoid and antibiotic shots to prevent the spread of disease.

After participating in South East Asian Treaty Organization (SEATO) exercises and Seventh Fleet operations, she cleared Yokosuka for the homeward voyage on 3 March 1960. Three days later in stormy waters about 1,200 miles off Wake Island she rescued four Soviets after they drifted 49 days in a disabled landing craft. They were flown back to their country after Kearsarge arrived at NAS Alameda, Calif., on 15 March. The Soviet Union thanked the carrier for her humanitarian gesture.

A year of training operations witnessed Kearsarge steaming in company with a number of other ships at times including John A. Bole (DD-755), Lofberg (DD-1059), and Taussig (DD-746), and escort ships Bridget (DE-1024), Evans (DE-1023), and Hooper (DE-1026). The training prepared the ship for her next deployment from San Diego on 3 March 1961. The antisubmarine carrier and Antisubmarine Carrier Air Group (CVSG) 53 steamed into trouble as they diverted to Southeast Asian waters. Ongoing attacks by communist Pathet Laotian insurgents threatened the stability of the royalist regime in Laos and the Seventh Fleet dispatched ships to the South China Sea to monitor the fighting on 21 March. Aircraft flew reconnaissance missions over Laos. The insurgents inflicted a defeat on the royalist and neutralist factions within Laos in April, however, and at times the Seventh Fleet also deployed Ranger (CVA-61), with CVG-9 embarked, and Ticonderoga (CVA-14), with CVG-5, to the area. The rival factions signed a cease fire later in the month, which enabled the carriers to come about on 5 May. Following six months in the Far East, Kearsarge arrived at Puget Sound on 1 November for the second phase of her modernization.

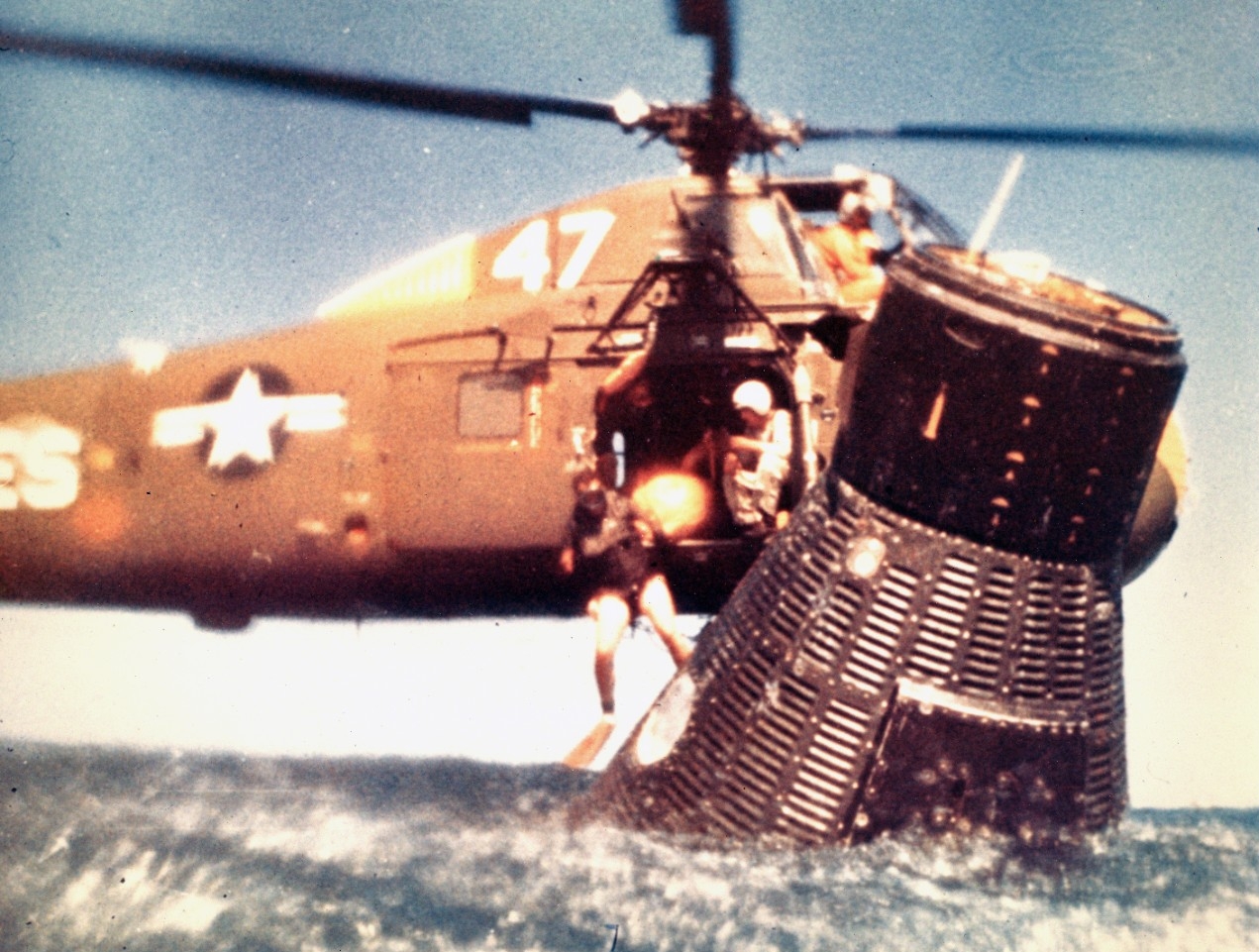

Upon completing that work, voyage repairs, and training, Kearsarge departed Long Beach, Calif., on 1 August 1962 for the Pacific Missile Range as a recovery ship in the space program. Cmdr. Walter M. Schirra piloted space capsule Sigma 7 during the launch of Mercury-Atlas-8 from Cape Canaveral, Fla., on 3 October 1962. Sigma 7 splashed down in the Pacific 275 miles northeast of Midway Island near 32°5'N, 174°28'W, and about 9,000 yards from primary recovery ship Kearsarge. Helicopters dropped swimmers near the capsule and Kearsarge hoisted Sigma 7 and Schirra on board the carrier. Additional vessels that supported the recovery included Lake Champlain (CVA-39) in the Atlantic. Kearsarge returned Schirra to Honolulu, H.I., for a flight back to the United States mainland, and on 16 October he received his astronaut wings.

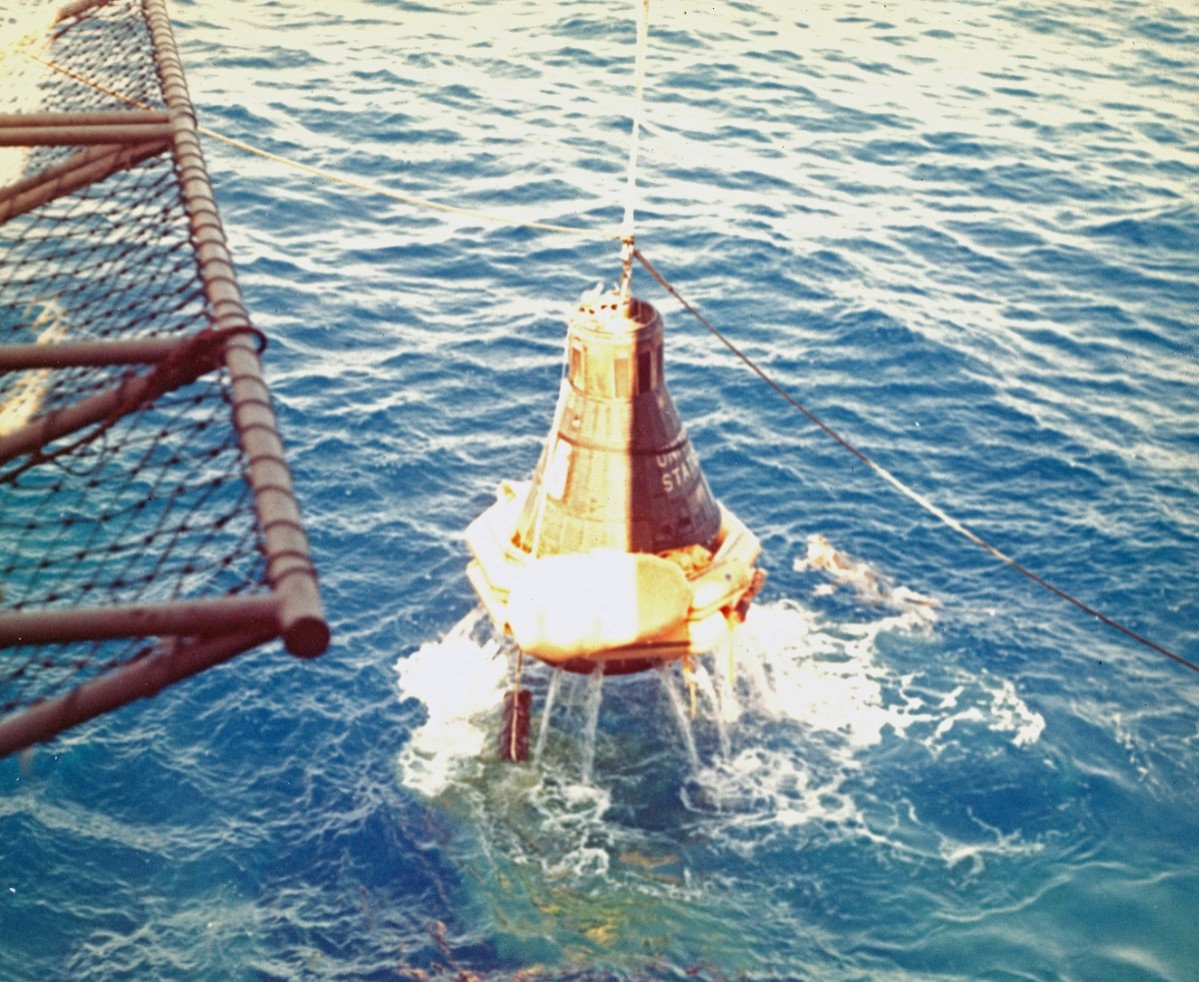

Kearsarge resumed training exercises for six months before loading CVSG-53 and steaming to Pearl Harbor, H.I. (19–29 April 1963) to once again take part in the space program. The ship refueled and provisioned and then turned seaward escorted by Fletcher (DD-445). The carrier’s crew spelling out “Mercury 9” on the flight deck as she made for the recovery area on 15 May. Capt. L. Gordon Cooper, Jr., USAF, piloted space capsule Faith 7 during the launch of Mercury-Atlas-9 from Cape Canaveral, Fla., on 16 May. Faith 7 splashed down in the Pacific about 80 miles southeast of Midway Island near 27°20'N, 176°26'W. The capsule impacted within 7,000 yards of primary recovery ship Kearsarge, which retrieved the spacecraft and the astronaut—swimmers dropped from helicopters to fix the flotation collar and retrieve the antenna fairing. Additional ships that supported the operation included Wasp in the Atlantic. Kearsarge returned Cooper to Pearl Harbor.

The ship departed on 4 June 1963 on her eighth cruise to the Far East, and while operating with the Seventh Fleet she kept watch on the fighting in Southeast Asia. Kearsarge returned to Long Beach on 3 December and took part in training exercises off California. Six months later, on 19 June 1964, the antisubmarine carrier deployed on her ninth Far Eastern cruise. Arriving at Yokosuka on 30 July, Kearsarge received orders dispatching her to the South China Sea in response to the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. Following the initial clashes President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered retaliatory air strikes and the U.S. launched Operation Pierce Arrow on 5 August. Constellation (CVA-64) and CVW-14, and Ticonderoga and CVW-5, launched 64 attack sorties against North Vietnamese vessels and facilities at five locations along that country’s coast at Bai Chay, Cua Hoi, Gianh River, and Lach Truong, and petroleum-oil-lubricants storage areas at Vinh. The attacks sank or damaged a number of vessels and destroyed petroleum stores and storage facilities. Antiaircraft fire shot down two aircraft over Hon Gai. While the two carriers and their consorts hurled their strikes against the North Vietnamese, Kearsarge helped fill the void they left in the Seventh Fleet’s deployed ships and provided antisubmarine patrols in the Western Pacific. Kearsarge returned to Long Beach on 16 December 1964, and after an overhaul during the first half of 1965, operated off the west coast.

Kearsarge, with CVSG-53 embarked, Rear Adm. Eli T. Reich in command, led a Hunter-Killer Group to the Western Pacific again (9 June–21 December 1966). The carrier joined Frank E. Evans in mid-day, and they sailed with Everett F. Larson (DD-830) and James E. Kyes (DD-787). They also operated with the aircraft from the carrier’s air group, which initially numbered 20 S-2E Trackers of VS-21 and VS-29, five E-1B Tracers of VAW-11 Detachment R, 21 Sikorsky SH-3A Sea Kings of HS-6, and a single C-1A Trader (BuNo 146023). The ships and aircraft worked up during multiple anti-air and anti-submarine drills along the way, including gun shoots at target drones, and again during an operational readiness evaluation in Hawaiian waters (15–17 June, and 20–25 June).

The ships sailed for anti-submarine exercise Crossed T III with U.S., Japanese, and South Korean vessels and aircraft as part of TG 70.4. Kearsarge led the group, which also comprised guided missile destroyer Cochrane (DDG-21), Everett F. Larson, Frank E. Evans, James E. Kyes, Radford (DD-446), Walker (DD-517), submarine Bonefish (SS-582), and Guadalupe (AO-32). The group sailed through the Tsugaru Strait into the Sea of Japan, and rendezvoused with Japanese ships Amatsukaze (DDG-163), Ayanami (DD-103), Isonami (DD-104), Shikinami (DD-106), and Uranami (DD-105).

The allies operated brazenly in proximity to waters the Soviets considered their own. As the ships came about they encountered dense fog as they worked their way on southerly courses through the Gulf of Tartary, a strait that separates the island of Sakhalin from the Asian mainland, on 27 July 1966. The visibility dropped and they manned fog details and repeatedly sounded fog signals. The Soviets showed interest in the proceedings and during the forenoon watch Soviet destroyer Veskiy (DD-022) suddenly emerged from the murk and shadowed the allied vessels. The latter moved into a circular formation, and Frank E. Evans and some of the other ships of the screen took turns steering various courses and speeds to work between the snooper, whom they dubbed “Mama Bear,” and the carrier.

The fog dissipated and with it the Kotlin class Soviet ship, but that afternoon the destroyer earned the appellation of Mama Bear when she returned with a pair of Komar class missile boats, which the Americans nicknamed “Baby Bears.” The trio closed and observed the allies before the Russians turned from the area on a northwesterly course at ten knots. Bonefish rejoined the formation on the afternoon of the 28th and the submarine also kept an eye on the intrusive Soviets. A pair of Soviet aircraft flew over Frank E. Evans’ bow from starboard to port at 1708, and shortly thereafter, their eavesdropping friend Veskiy returned and shadowed them throughout the night. Frank E. Evans and Walker took turns conducting “shouldering tactics” against their Cold War adversary. In the midst of these confrontations, a helo flew over from Kearsarge and hoisted Ens. Ray M. Messinger, the destroyer’s electronics material officer, aloft and to the carrier for a briefing on the Soviets, and then returned him to the ship. The Japanese in the meantime broke off and returned to their ports.

The Americans continued to churn southward and on the 29th rendezvoused with South Korean destroyer Chungmu (DD-91), ex-Erbin (DD-631), Chungnam (DE-73) ex-Holt (DE-706), Kang Won (DE-72), ex-Sutton (DE-771), and Kyong Ki (DE-71), ex-Muir (DE-770), and frigates Duman (PF-61), ex-Muskogee (PF-49), Imchin (PF-66), ex-Sausalito (PF-4), and Naktong (PF-65), ex-Hoquiam (PF-5). The two navies carried out a number of exercises, and two of the ship’s crewmen embarked on board a South Korean ship for three days. The men returned complimenting their hard working allies but complained about the food, which consisted largely of a repetitive menu of cabbage and rice. As they began the exchange on the afternoon of the 29th, Frank E. Evans’ sonar operators detected a Russian submarine and lost her again in the “baffles,” only to reacquire the contact. The slippery boat played a cat-and-mouse game with the ship, turning and diving to break contact, and then inadvertently revealing herself again until she maneuvered out of detection. The Americans and South Koreans concluded their training and detached, the latter turning for home, and the former for Japanese waters.

Kearsarge subsequently turned for the Vietnam War. At times Kearsarge and ships of DesDiv 231: Cochrane, Frank E. Evans, James E. Kyes, Radford, and Walke (DD-723) operated in the Gulf of Tonkin in the South China Sea, beginning on 8 August 1966. Stores issue ship Castor (AKS-1) also joined them for some of their deployment.