Charles Drew (T-AKE-10)

2010-

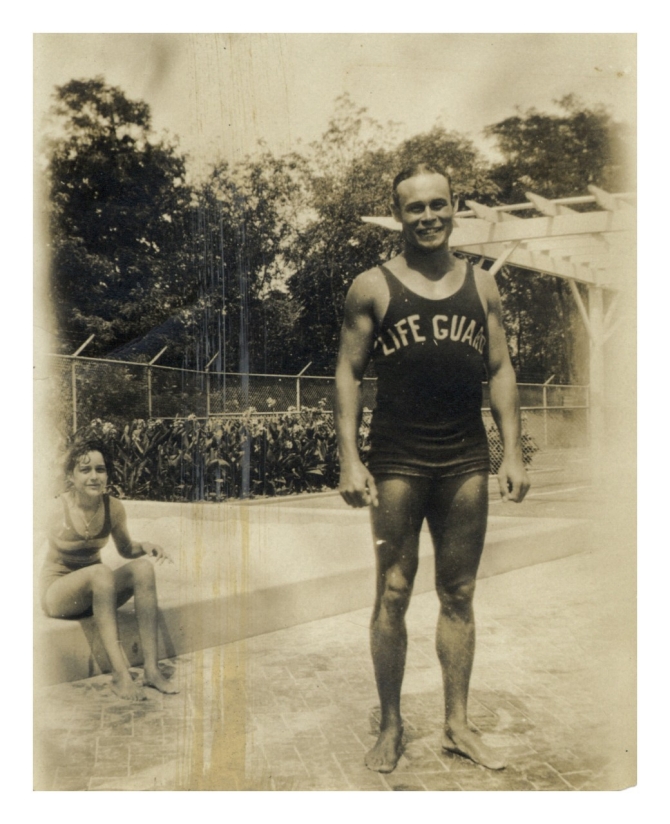

Charles Richard Drew was born in Washington, D.C., on June 3, 1904 to Richard and Nora B. Drew. His father worked as a carpet layer and financial secretary of the Carpet, Linoleum, and Soft-Tile Layers Union, and as its only African American member. His mother graduated from the Miner Normal School, but never worked as a school teacher. Charles and his younger siblings, Joseph, Elsie, and Nora, grew up in the largely middle-class and interracial neighborhood of Foggy Bottom. Their upbringing emphasized academic education and church membership, as well as civic knowledge and personal competence, responsibility, and independence. Charles became a paper boy at the age of twelve, selling several Washington papers from a street corner stand. He subsequently worked after school and during the summers supervising at city playgrounds, lifeguarding at the local swimming pool, and in construction.

Drew attended Stevens Elementary, and then Dunbar High School, a college preparatory school. He excelled at athletics, lettered in four sports, and won the James E. Walker Medal for all-round athletic performance in both his junior and senior years. He also served as captain of Company B in the Third Regiment of the High School Cadet Corps during his senior year. His fellow students voted him: “best athlete,” “most popular student," and “student who has done the most for the school.” Drew did not express any early medical ambitions, his senior yearbook entry noted that he aspired to become an electrical engineer. During that period, Drew’s family moved to Arlington, Virginia, where his third sister, Eva, was born in 1920. That same year, however, his oldest sister, Elsie, died from tuberculosis complicated by influenza.

Drew graduated from Dunbar in 1922 and attended Amherst College, Mass., on an athletic scholarship, excelling in track and football. While Drew did not excel scholastically, Dr. Otto C. Glaser, a member of the medical sciences faculty, inspired the young student-athlete through his biology courses. Drew later reflected that his work with Dr. Glaser, his sister Elsie’s death, and his hospitalization for a college football injury collectively fostered his interest in medicine. Drew received his AB from Amherst in 1926, then earned money for medical school by working as the athletic director and instructor of biology and chemistry at Morgan College (now Morgan State University), in Baltimore, Md. During his two years at Morgan, his coaching transformed its sports teams into serious collegiate competitors.

Racial segregation constrained Drew’s options for medical training. Some prominent medical schools, such as Harvard, accepted a few non-white students each year, but most African Americans aspiring to medical careers trained at black institutions, such as the Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, D.C., or Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tenn. Drew applied to Howard but was rejected because he lacked enough credits in English from Amherst. Harvard accepted him, but wanted to defer his admission to the following year. Drew learned that the McGill University Faculty of Medicine in Montréal, Canada, admitted a diverse range of students, and he attended there. McGill University allowed its graduate and professional students to play on school teams, and Drew once again became a star athlete, though attained several important academic prizes and fellowships, and graduated second in a class of 137, in 1933.

During his internship and surgical residency at Montréal General Hospital (1933–35), he worked with bacteriology Dr. John Beattie of the Royal College of Surgeons. Beattie’s work methods to treat shock with transfusion and other fluid replacement ignited Drew’s interest in transfusion medicine. Drew hoped to extend his training with a surgical residency in the United States, preferably at the Mayo Clinic, but major American medical centers rarely took on African American residents, partly because many white patients in that era would refuse to be treated by black physicians. He therefore joined the faculty at Howard as a pathology instructor in 1935, and then progressed to surgical instructor and to chief surgical resident at Freedmen’s Hospital.

The Rockefeller Foundation’s General Education Board enabled Howard to improve enhance its programs, and some white department chairs consequently established residency programs and fellowships for African Americans. Drew trained with Dr. Edward L. Howes, the Department of Surgery’s chair, for three years. He then attained a fellowship to train with surgeon Dr. Allen O. Whipple at New York’s Presbyterian Hospital, while earning a doctorate in medical science from Columbia University. While at Presbyterian, he also worked with Dr. John Scudder on studies relating to treating shock, fluid balance, blood chemistry and preservation, and transfusion. Drew wrote his dissertation with Scudder on an experimental blood bank at Presbyterian, which opened in August 1939.

While attending a conference in April 1939, Drew met Minnie L. Robbins, a professor of home economics at Spelman College in Atlanta, Ga. They married on 23 September of that year, and had three daughters, Bebe, Charlene, and Rhea, and a son, Charles, Jr. They named their eldest daughter, Bebe, born in 1940, for the blood bank (BB). Drew received his doctorate in medical science from Columbia in June 1940, becoming the first African American to earn the degree there.

Drew returned to Howard as an assistant professor of surgery. The British desperately needed blood and plasma (the fluid, non-cellular portion of blood) to treat casualties during “The Blitz,” the German bombing of their cities. In August 1940, Presbyterian and five other New York hospitals began a collaborative effort to collect and ship plasma to the British. Drew was called back to New York to direct the Blood for Britain project the following month. Other researchers had developed the basic methods for plasma use, but Drew instituted uniform procedures and standards for collecting blood and processing blood plasma at the participating hospitals.

The program ended in January 1941, and Drew began work as the assistant director of a pilot program for a national blood banking system, jointly sponsored by the National Research Council and the American Red Cross. His innovations included mobile blood donation stations, later called “bloodmobiles”, but the armed forces initially stipulated that the Red Cross exclude African Americans from donating; thus preventing Drew from participating in the program he helped establish. The War Department eventually modified the policy to accept blood donations from blacks, but segregated the blood collected. Throughout the war, Drew criticized these policies as unscientific and insulting to African Americans.

Drew passed his American Board of Surgery exams and received certification in April 1941. He returned to Howard, and in October became chair of the Department of Surgery and Chief of Surgery at Freedmen’s Hospital. He also became the first African American to be appointed an examiner for the American Board of Surgery. For the next nine years he trained and mentored medical students and surgical residents, and raised standards in black medical education. He also campaigned against the exclusion of African American physicians from local medical societies, medical specialty organizations, and the American Medical Association.

Drew gained recognition of work: he received the E. S. Jones Award for Research in Medical Science from the John A. Andrew Clinic in Tuskegee, Ala., in 1942; an appointment to the American-Soviet Committee on Science in 1943; the 1944 Spingarn Medal from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), for his work on blood and plasma; honorary doctorates from Virginia State College in 1945 and Amherst College in 1947; and election to the International College of Surgeons in 1946.

He became the Medical Director at Freedmen's Hospital (1946–48), and the following year a consultant with the U.S. Army Surgeon General’s Office, part of a team to assess health care in post-war Europe. Drew died in Burlington, N.C., on 1 April 1950, from injuries sustained in a car accident while en route to a conference. Drew’s tragic death generated a persistent myth that he died because the white hospital denied him admission (or a transfusion), however, the white physicians cared for him promptly and competently, but his injuries proved fatal. Drew left a substantial legacy, embodied in his blood bank work and especially in the graduates of the Howard University College of Medicine.

(T-AKE-10: displacement 42,528; length 689; beam 106'; draft 30'; speed 20 knots; complement 197; armament up to 6 .50 caliber or 7.62 millimeter machine guns, aircraft 2 Sikorsky MH-60S Knighthawks or 2 Eurocopter (Aérospatiale) AS332 Super Pumas; class Lewis and Clark)

Charles Drew (T-AKE-10) was laid down on 13 March 2009 at San Diego, Calif., by General Dynamics National Steel and Shipbuilding Co.; launched on 27 February 2010; sponsored by Mrs. Bebe D. Price, Dr. Drew’s eldest daughter; and was placed in service with the Military Sealift Command on 14 July 2010.

Shield

Dark blue and gold represent the Navy. The scarlet cross symbolizes the medical profession and the American Red Cross, which provided enough blood for more than six million plasma packages by the end of World War II. Dr. Drew served as the director of the Red Cross blood bank and assistant director of the National Research Council in charge of blood collection for the U.S. armed forces. He invented the “Plasma for Britain” process by which blood plasma could be packaged and shipped safely and stored until needed. The lion represents the United Kingdom, the main beneficiary of the program, and also denotes determination and courage. The open book refers to Howard University, where Drew became head of the Department of Surgery, and recalls his contributions as a teacher at Howard and at the Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital in New York. The goutte field of drops represents the processed plasma and numbers ten, a reference to the ship's designation. White denotes vision and integrity.

Crest

The water-bouget, a traditional heraldic charge denoting the carrying of water and other liquids, represents a mission element of the new ship, to transport a variety of materiel and cargoes. With the British Union Jack it also symbolizes the World War II transportation of plasma and associated blood products across the Atlantic to the British Isles, which Drew helped organize and administer. The color scarlet represents blood and plasma technology. The staff of Asclepius symbolizes Drew’s medical expertise and his contributions to the field of blood and transfusion processes. Dark blue and gold represent the Navy.

Typhoon Haiyan/Yolanda cut a wide swath of destruction across the Central Philippines, killing more than 6,000 people (6–9 November 2013). Multiple U.S. ships and aircraft raced to the Philippines during Operation Damayan, humanitarian assistance to the victims of the disaster. Charles Drew took part in Damayan, and MH-60S Seahawks of Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron 25 delivered fresh water and food from the ship to the people of Ormoc City and the surrounding villages on Leyte. “We produced ice by placing water in bags inside of boxes and then we froze it,” Norflis McCullough, Charles Drew’s supply officer, afterward explained. “We started the whole process six days before we started delivering it to areas in the Philippines.” Air Survival Equipment Specialist 2d Class Peter Glatt recalled: “After we delivered the water and supplies, the people were waving their hearts out as we flew away. It felt really good to help.”

Detailed history under construction.

Mark L. Evans