Kentucky I (Battleship No. 6)

1900–1922

The first U.S. Navy ship named in honor of the 15th state of the Union admitted on 1 June 1792.

I

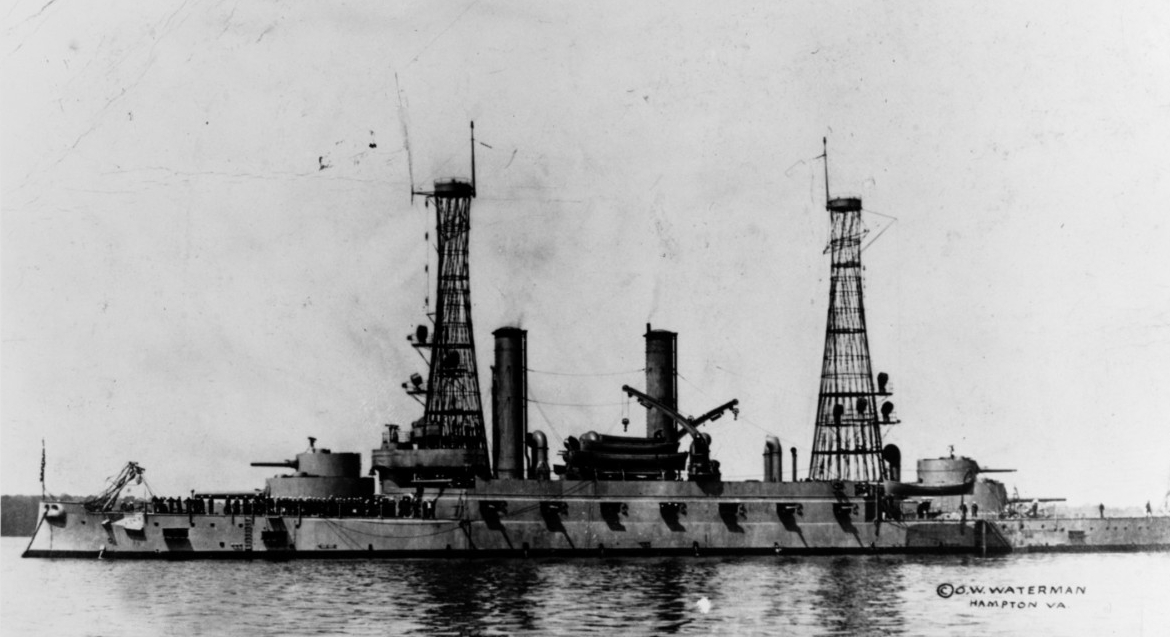

(Battleship No. 6: displacement 11,540; length 375'; beam 72'; draft 23'6"; speed 17 knots; complement 554; armament 4 13-inch, 4 8-inch, 14 5-inch, 20 6-pounder rapid-fire, 4 1-pounder rapid-fire, 4 Maxim-Nordenfelt semi-automatic 1 pounders, 8 M1895 Colt-Browning machine guns, 2 3-inch rapid-fire field guns [landing force], 4 18-inch torpedo tubes; class Kearsarge)

In December 1894, President Glover Cleveland asked the Congress to authorize three new battleships. Politicians debated the ships’ cost and dropped one of the vessels from the program. On 2 March 1895, the Congress authorized two “seagoing coast line battleships designed to carry the heaviest armor and most powerful ordnance upon a displacement of about ten thousand tons” — which were subsequently named Kearsarge (Battleship No. 5) and Kentucky (Battleship No. 6).

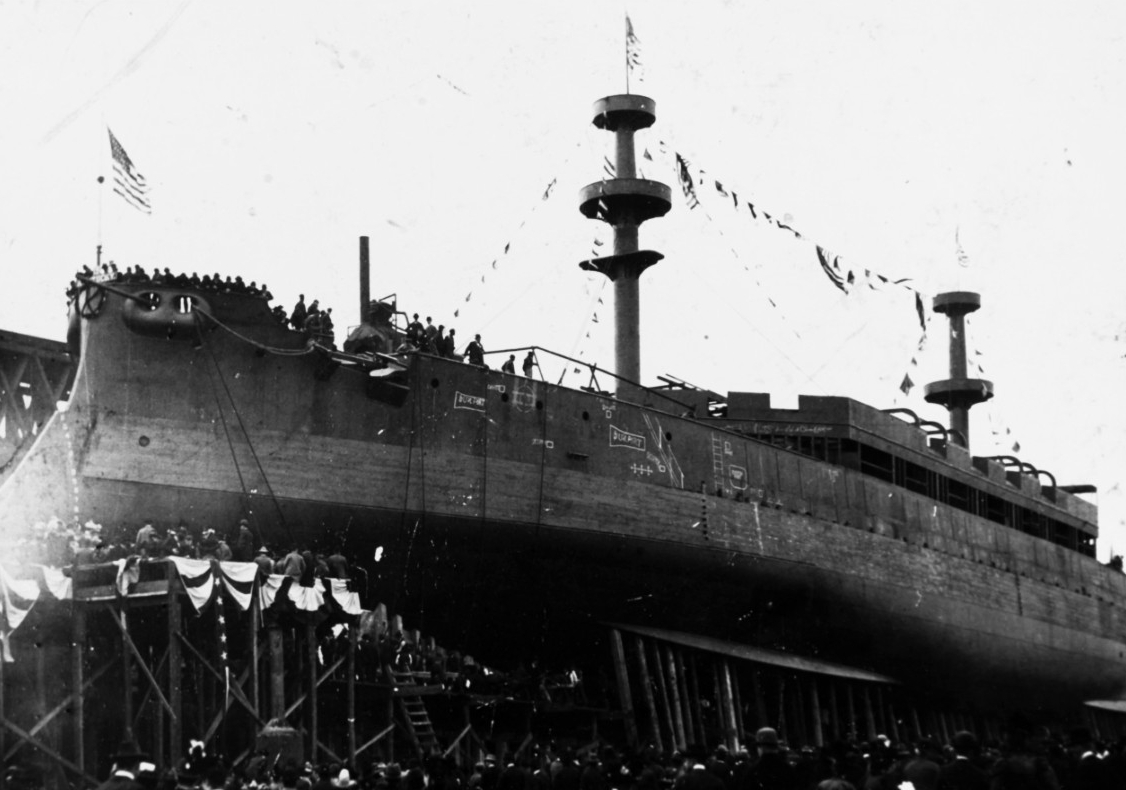

The second Kentucky (Battleship No. 6) was laid down on 30 June 1896 at Newport News, Va. by Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co.; and sponsored by Miss Christine S. Bradley, daughter of Governor William O’Connell Bradley of Kentucky.

Both Kearsarge class ships displayed very distinctive silhouettes, in large part because of their main batteries. “The two battleships have been designed,” Rear Adm. Frank M. Bennett wrote in The Steam Navy of the United States: A History of the Growth of the Steam Vessel of War in the U.S. Navy, and of the Naval Engineer Corps in 1896, “for 11,500 tons displacement, and will be in general very much like the Iowa (Battleship No. 4) in build and design and arrangement of machinery. A decidedly new feature has been adopted for these big ships in locating the turrets for the 8-inch guns on top of the 13-inch gun turrets.”

Well-armed and rugged for their size, the ships nonetheless encountered problems. The designers claimed -- and later gunnery tests proved -- that the guns’ muzzle blast would not interfere with the two different batteries, but their arrangement prevented the 8-inch guns from firing separately. In addition, an enemy shell striking one of the 13-inch turrets or a mechanical failure could knock out half of the main battery in a single stroke. The 13-inch turrets furthermore had large ports to enable the guns to train to their full vertical elevation (15° elevation and 5° depression), which critics claimed marked a potentially fatal design flaw. Lt. William S. Sims served in Kentucky (7 November 1900–4 March 1901), and went on to command U.S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters during World War I. Sims observed that a hit on one of Kentucky’s 13-inch gun ports could knock out the guns, and possibly ignite the powder bags in the turret and in the open shell hoist, triggering a catastrophic explosion. In addition, their low freeboard generally rendered the 5-inch broadside guns unusable in heavy seas.

Kentucky was launched on 24 March 1898, alongside Kearsarge during a surge of patriotism following the sinking of second-class armored battleship Maine in Havana, Cuba, on 15 February 1898. An estimated 20,000 people converged on Newport News for the launching, taxing the area’s accommodations and communications. The Chesapeake & Ohio Railway ran several excursion trains to help alleviate the crush, and chartered Chesapeake Bay steamers carried additional people from Baltimore, Md., and Washington, D.C. Crewmen on board Brooklyn (Cruiser No. 3) and monitor Puritan viewed the ceremony from their ships when they anchored nearby, and people packed the shipyard piers and spilled over onto the river bluffs to watch the proceedings.

Governor Bradley and his family were teetotalers and the governor felt that water from a Kentucky spring would better represent the state than champagne, the latter most likely from another country. Christine Bradley thus christened the ship with a cut-glass bottle of water from Sinking Spring Farm, President Abraham Lincoln’s birthplace. Disappointed Kentuckians in the crowd countered by breaking bottles of bourbon upon Kentucky’s hull as well as water from the spring of the late President of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis’ farm. The Kentucky Women’s Christian Temperance Union subsequently presented Ms. Bradley with an engraved silver water set, though the governor’s daughter later remarked that she felt “very guilty” about accepting, since her father recommended the controversial use of the water. The two battleships slid down the ways into the James River, Kearsarge first at 10:02 a.m., followed by her sister a little over an hour later at 11:35. People in the crowd repeatedly cheered as the ships entered the water, and the shrill whistles of the vessels in the harbor welcomed the battleships to the briny deep. Steamer Newport News then took 600 guests to a banquet held at Old Point. Kentucky subsequently reached a flank speed of 16.9 knots on her trials, just under her designed speed, and was commissioned on 15 May 1900, Capt. Colby M. Chester in command.

After fitting out at New York Navy Yard that summer, Kentucky sailed on 25 October 1900 for the Far East via Gibraltar and the Suez Canal. She joined the other American ships on the Asiatic Station at Manila in the Philippines on 3 February 1901, and six days later sailed for Hong Kong, where she became the flagship of the Southern Squadron under Rear Adm. Louis Kempff on 23 March. While Kentucky steamed on the Asiatic Station her ship’s company included an additional member — Nanny de Goat. The crew good naturedly prepared a rating report of their goat mascot:

‘Appointed from civil life, from Kentucky.

Attained present grade; 15 May, 1900.

Previous sea service: none. First cruise.

Proficiency in rating: 5. Obedience: 3. Sobriety: 2.5.

Rating best qualified to fill: Compartment cleaner.

Recommended for Good Conduct medal: No.’

Throughout the following year the battleship led her squadron as she watched over American interests in the Far East, and initially ventured into Chinese waters. Rear Adm. Frank F. Wildes selected Kentucky as his flagship upon relieving Kempff on 1 March 1902, but on 1 April he transferred his flag to Rainbow (Submarine Tender No. 7). Kentucky celebrated Independence Day 1902 in company with protected cruiser New Orleans at Kiauchau [Jiaozhou], China, and joined New Orleans and Vicksburg (Gunboat No. 11) for small arms target practice, torpedo practice, sea target practice, and an admiral’s inspection at Chefoo [Yantai] (6–23 July). Accompanied by New Orleans and sidewheel gunboat Monocacy she next (24–25 July) lay to off the Taku Forts [Tanggu District], which international troops had stormed just two years before during the Boxer Rebellion. From there, the battleship and the cruiser crossed the Gulf of Chihli [Bohai Sea] to the Russian fortress of Port Arthur [Lüshunkou District] (26–28 July), where Helena (Gunboat No. 9) rendezvoused with them, and the trio then returned to Chefoo (28 July–6 August). Whenever Kentucky lay to in tropical waters crewmen often opened the fore and aft 6-pounder casemates to gain at least some relief from the sweltering heat.

Kentucky turned her prow toward unfamiliar waters and in company with New Orleans, Helena, and Vicksburg carried out squadron evolutions off Chemulpo [Incheon], Korea (7–10 August). The four increasingly seasoned ships shaped courses for Japanese waters and reached Nagasaki, Kyūshū (13–15 August), where auxiliary cruiser Buffalo rendezvoused with the squadron. Kentucky and Yorktown (Gunboat No. 1) carried out a rare visit to the Russian port of Vladivostok, Siberia (17–23 August), and the battleship returned to Japanese waters and put in to Hakodate on Hokkaido (24–27 August), and passed through the Tsugaru Strait and followed Honshū southward, and in company with New Orleans, Vicksburg, and Yorktown visited Yokohama (29 August–19 September). Kentucky set out from that port, rounded Honshū, and crossed the East China Sea to call at Woosung [Wusong], China (23 September–18 October). While there, the ship carried out a full speed and forced draft trial, and coaled from torpedo flotilla tender Pompey, and some of her men visited the bustling city of Shanghai.

The battlewagon doubled back to Yokohama (22 October–14 November), where Rear Adm. Robley D. Evans, Commander in Chief, Asiatic Fleet, broke his flag in Kentucky on 4 November; and he continued to direct American naval operations in the Far East from her until she sailed from Manila for home (see 13 March 1904). Kentucky came about again for Chinese waters to take part in a fleet drill with both the Northern and Southern Squadrons off Amoy [Xiamen] (19 November–3 December). She then coaled from Pompey at Hong Kong (4–15 December), along with New Orleans, monitor Monterey, and Helena, Vicksburg, and Yorktown. Kentucky wrapped-up the year by spending the holidays in the Philippines, where she held small arms practice at Cavite Island (18–24 December), spent Christmas at Manila, and then visited Olongapo at Subic Bay over New Year’s Eve (26 December 1902–6 January 1903).

Through the winter the ship carried out target practice, fleet drills, night target shooting, small arms practice, and coaled, alternatively between Manila and Cavite. Kentucky joined New Orleans and colliers Nanshan and Zafiro for a unique visit to Labuan on North Borneo (22–26 February 1903), and then (1–7 March) slid into the crowded harbor at Singapore. The ship returned to Hong Kong, where she joined Oregon (Battleship No. 3), New Orleans, Helena and Isla de Cuba, and Pompey (13 March–4 April). Kentucky, New Orleans, and Helena swung northward and visited Amoy (5–7 April) and next (9–12 April) lay to off the mouth of the Yangtze River. Kentucky, New Orleans, Helena, and Vicksburg visited Nagasaki (14–17 April), and next (20 April–15 May) joined Oregon, gunboats Don Juan de Austria, Princeton, and Yorktown, and Supply (a fittingly named supply ship) at Yokohama. The voyages wore heavily on Kentucky and she completed work in dry dock at Yokosuka (16–25 May) and then worked-up in Japanese waters, which included a forced draft trial off Rokuren Light (2–3 June).

Kentucky returned to China that summer and visited Chefoo (5–9 June 1903) followed by Taku (10–17 June). In company with Oregon, New Orleans, monitor Monadnock, Don Juan de Austria, Helena, Monterey, Vicksburg, Wilmington (Gunboat No. 8), Nanshan, and Pompey, and screw tug Wompatuck she returned to Chefoo for a variety of training evolutions on 18 June. The battleship continued to ply those trade routes, charting courses between multiple ports while protecting Americans until she sailed from Manila for home on 13 March 1904. After retracing her passage through the Suez Canal and the Strait of Gibraltar, she accomplished repairs in dry dock at New York Navy Yard (23 May–26 October). Kentucky alternatively coaled and provisioned, carried out her post-yard full-power trials, and trained with the North Atlantic Fleet off Sandy Hook, N.J., and Tompkinsville, on Staten Island, N.Y., into the winter, culminating with a naval review and fleet training exercises off Hampton Roads (29 December 1904–9 January 1905).

The battleship shaped a course for warmer waters when (15 January–7 May 1905) she took part in fleet maneuvers in the Caribbean. Kentucky trained off Culebra Island, P.R. (15 January–17 February) and then (19 February–18 March) Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. The ship followed those operations with a visit to Havana (20–25 March), and turned northward and carried out full-power trials, and forced and natural draft tests off Pensacola, Fla. (27 March–2 May) before returning home. Kentucky participated in fleet evolutions with Division 1 off the Southern Drill Grounds (15–19 and 23–26 May and 31 May–3 June), returning in between each exercise to Hampton Roads, after which she stood into the North River at New York, at times in company with her sister ship Kearsarge (8–11 June).

Kentucky conducted repairs in dry dock at New York Navy Yard (11–27 June), and then (29 June–12 July) held a forced draft trial off Provincetown, Mass. The ship continued her summer sojourn into those waters and took part in a search problem with Division 3 off Newport, R.I. (13–19 July). The fleet stood into the North River so that the ships’ liberty parties could venture into the teeming metropolis (27 July–1 August), and then operated off New England and visited Bar Harbor and Portland, Maine (3–11 and 11–15 August, respectively). She came about and moored to Narragansett Pier, R.I. (18–19 August), visited Provincetown (29 August–11 September), then (11–28 September) fired her guns on the range in Cape Cod Bay. The ship concluded the cruise by standardizing her screws on the 29th, and conducting a survey for likely repairs once she returned to Hampton Roads on the 1st of the month. Despite any potential maintenance issues, the vessel resumed her operations and cruised with the North Atlantic Fleet (4–12 October), which included a visit to 79th Street at New York.

British Adm. Prince Louis Alexander of Battenberg, who broke his flag in armored cruiser Drake, led five other armored cruisers of the Royal Navy’s Atlantic Fleet, Second Cruiser Squadron -- Bedford, Berwick, Cornwall, Cumberland, and Essex -- on a goodwill voyage along the east coast. Kentucky sailed as one of the ships that welcomed the Prince during his visit to the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md. (30 October–7 November), and then (8–20 November) continued with the British ships to the now familiar 79th Street. Kentucky next completed repairs at the navy yards at Norfolk and New York (21–28 November and 29 December 1905–7 January 1906, respectively).

The New Year opened inauspiciously for Kentucky when Rear Adm. Evans took five battleships of the North Atlantic Fleet from New York to sea, bound for Hampton Roads, at 11:15 a.m. on 7 January 1906. Evans led the column in his flagship, Maine (Battleship No. 10), displaying the signal “Follow the flag,” and followed (in order) by Kentucky, Kearsarge, Alabama (Battleship No. 8), and Illinois (Battleship No. 7). Rear Adm. Charles H. Davis, the divisional commander, flew his flag in Alabama. The fleet proceeded at a speed of seven to eight knots but battled strong wind and high tide eddies that swung Kentucky nearly a half mile off the main channel, and Kearsarge, which followed at a 400 yard interval, to the westward. Kentucky lowered her speed and struggled for a few minutes, but at about noon went aground in nearly ten feet of mud off the northwest point of the East Bank, approximately a mile and a half south of Norton’s Island and two miles east of West Bank Light.

Kearsarge attempted to veer to the eastward to avoid her sister but vainly fought the heavy wind and tide and ran aground in order to avoid colliding with Kentucky. Alabama steamed about 800 yards from Kentucky but had way on and slammed into Kentucky on her starboard quarter, seriously damaging Kentucky and tearing a large hole in her own bow. The impact tore away Kentucky’s starboard quarter rail and heavy steel davits, and sliced the captain’s gig (boat) in two. Alabama’s collision buckled a number of Kentucky’s plates from the waterline to the superstructure, and most likely damaged her steering gear. The shock ripped open a 15-foot gash in Alabama’s port bow above the waterline, dented plates, and tore off most of the port rail and some davits. The ships did not report serious casualties.

Illinois overcame the tide, turned into the main channel, and avoided her companions. Alabama continued to the Southwest Split, where she came about and drew alongside Kentucky to render assistance. The distressed ships sent a plea for help by wireless telegraph to Rear Adm. Joseph B. Coghlan, the commandant of the nearby navy yard, who dispatched tugs Apache, Powhatan, and Uncas. The trio reached the scene by about 2 p.m., but Kearsarge and Kentucky freed themselves without the tugs’ help and rendezvoused with Maine, which had reached the area off Sandy Hook. Evans ordered Kentucky to detach from the fleet and return to the navy yard for repairs, Alabama made temporary repairs, and at 5:25 p.m. Alabama, Illinois, Kearsarge, and Maine resumed their voyage.

“These conditions explain the whole situation,” Rear Adm. Davis explained concerning the weather to journalists on board Alabama shortly after the accident, “There is hardly any comment to be made. Such accidents always are likely under conditions such as we had today in a narrow channel.”

Kentucky returned first to Tompkinsville, where a diver examined her hull and ascertained the extent of the damage, and then (8–21 January 1906) completed repairs at New York Navy Yard. The newly repaired battleship devoted the rest of the year for tactics and maneuvers off the Atlantic coast and in the Caribbean with the North Atlantic Fleet. The ship turned her prow southward for a cruise that carried her to the waters off Culebra Island (26 January–6 February), followed (8–14 February) by a fleet scouting problem off Port of Spain, Trinidad. Kentucky standardized her propellers, carried out tactical evolutions, small arms target practice, and mining operations off Guantánamo Bay (19 February–31 March), and next (1–14 April) shot at targets and standardized her screws off Cape Cruz, Cuba. The ship returned to Guantánamo Bay to coal and then (24–26 April) qualified her 5-inch gun pointers while firing at the range off Cape Cruz. Kentucky conducted full-power trials off Guantánamo Bay and on the 28th set out with the fleet for home, reaching Tompkinsville on 3 May. The ship joined some of the other vessels for a visit to 79th Street (4 May–1 June), and after briefly putting in to Provincetown, returned to Hampton Roads on 5 June.

The veteran battleship set out for another voyage to New England waters that summer when she sailed on 16 July, and two days later (18–26 July) completed work in dry dock at Boston Navy Yard, Mass. Kentucky attempted to return to sea to rendezvous with the fleet but dense fog bound the ship at President Roads off that harbor overnight. The fog finally cleared and she rejoined the fleet off Rockport, Mass. (27–30 July), and next (31 July–1 August) coaled at Bradford, R.I. Kentucky took part in tactical evolutions with the fleet along the New England coast, and followed that by a visit to North River for coal and liberty (19–25 August), and then (27–29 August) stood back out to sea and cruised with the fleet off Rockland.

The ship broke her operations and took part (29–30 August) in ceremonies in connection with the unveiling of a monument to Quartermaster William Conway at Camden, Maine. The memorial honored Conway’s “sturdy loyalty” for refusing to haul down the Stars and Stripes when the Confederates seized Pensacola Navy Yard on 12 January 1861.

Kentucky hove to off Smithtown Bay on Long Island Sound, N.Y., while she prepared (1–2 September) for President Theodore Roosevelt to review the fleet off Oyster Bay on the sound (2–4 September). Following the chief executive’s review, the ship turned northward and operated off Bar Harbor and Provincetown (6–23 and 24–25 September, respectively), and on the 18th took part in Bar Harbor’s Water Festival.

The crew prepared for the festival by converting Kentucky’s first steamer into a model of their ship, which they named Baby Kentucky. Men removed the steamer’s canopy and covered her with false wood work. The carpenter and his staff wrought guns and turrets to scale, and the electrical staff installed a complete set of ship’s illuminating gear, together with the ship’s name in letters of the right proportion and an Ardois signaling system, using standard 5 candle power 80 volt lamps with miniature bases. The radio team removed a 1 ¼ K.W. Slaby Arco mercury turbine interrupter transmitter from their battle station and installed it in Baby Kentucky. They used two pieces of annunciator wire for an antenna, and small pieces of wood about 8-inches long for the spreaders. A 3 H.P. motor from a 5-inch ammunition hoist powered the lighting and radio transmitter, and they uncoupled the launch’s propeller and by means of pulleys and a belt plus racing the engine generated 80 volts while using the motor as a generator — they operated the vessel under tow. The men considered using the call letters “KY” as appropriate to the occasion, and operated their scale battleship as an entry in the festival. The chief radio electrician lay on his stomach in the crowded quarters and stifling heat to work the key, but did so successfully and Baby Kentucky responded well to her orders. The “Devil’s Tongue” type of boiler, under forced draft for most of the carnival, burnt the paint off the forward funnel of the miniature vessel. Other ships entered their own entries in the festival and Indiana (Battleship No. 1) converted one of her sailing launches to resemble Santa María, Christopher Columbus’ flagship. Following the festival the men dismantled their prized Baby Kentucky and restored her to the ship’s steamer.

Cuban liberals led a revolt against that country’s President T. Estrada Palma in August 1906. Both sides requested U.S. support, and President Roosevelt directed the War Department and the Navy Department to dispatch ships and troops to protect Americans caught in the conflict, actions that gave rise to the second U.S. occupation of Cuba. Three marine battalions sailed on board Minneapolis (Cruiser No. 13), Newark (Cruiser No. 1), and Tacoma (Cruiser No. 18) on 18, 17, and 16 September, respectively. Kentucky lay off Provincetown on 25 September while the ship prepared for target practice when she received orders to embark marine guards from Kearsarge, Maine, and Missouri, join Indiana, and make speed for Cuban waters. Indiana and Kentucky brought a total of 804 marines on board, steamed southward, and reached Havana on 1 October.

The crisis continued and two additional marine battalions set out for Cuba on board battleship Texas, Brooklyn, and transport Prairie on 1, 2, and 1 October, respectively. Their arrival raised the number of marines available for the landing force to 2,892 men (97 officers and 2,795 enlisted marines), which formed the 1st Provisional Brigade, Col. Littleton W.T. Waller, USMC, in command. The marines served under naval jurisdiction, but the confrontation gradually lessened and some of them returned to their various ships and stations. Kentucky stood by and supported the landing force, first off Havana, and then at Matanzas (1–6 October), and back to Havana until the 9th, when she came about for the United States. The Navy disbanded the brigade on 1 November, and formed the 1st Provisional Regiment to continue operations as part of the Army of Cuban Pacification, which the regiment did until it returned to the United States on 23 January 1909.

“It was owing in large part to the General Board,” President Roosevelt wrote in a message to the Congress on 3 December 1906, “that the Navy was able at the outset to meet the Cuban crisis with such instant efficiency; ship after ship appearing on the shortest notice at any threatened point, while the Marine Corps in particular performed indispensable service.”

Kentucky resumed battle practice and tactics in the North Atlantic and shot at targets on the range in Cape Cod Bay (13–23 October), following which she took part in mining practice off Provincetown through the 26th. Two days later she took on board “certain ordnance gear” for Norfolk Navy Yard, and then completed repairs there and in dry dock at New York Navy Yard (29 October–16 December and 17–28 December 1906, respectively).

The battleship rejoined her consorts at Hampton Roads just before the New Year, and soon (2 January–15 April 1907) set her bow southward for fleet maneuvers in the Caribbean. Kentucky worked in the waters off Guantánamo Bay through 10 February, called at Ponce, P.R. (12–15 February), and shot at targets off Guantánamo Bay before returning to Hampton Roads. There she participated (15 April–13 June) in a portion of the Jamestown Exposition, commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown Colony, held at Sewell’s Point, Hampton Roads. Her part included a Presidential Naval Review off the roads (7–10 June), after which (14 June–15 July and 17 July–2 August, respectively) she completed repairs at Norfolk Navy Yard and in dry dock at Boston Navy Yard. Kentucky’s four broadside torpedo tubes were removed at around this time, and wireless antennae added.

Kentucky visited the North River (4–9 August) and trained in New England waters, a voyage that included attempting to fend off torpedo boats during an exercise off Newport (12–15 August). The ship then (16–21 August) took part in a problem off Cape Cod and visited Provincetown, where President Roosevelt officiated at the laying of the Pilgrim Monument’s cornerstone on the 20th. The memorial, the completion of which President William H. Taft dedicated on 5 August 1910, commemorated the Pilgrims’ first landfall and their signing of the Mayflower Compact in 1620.

The ship swung around and returned to Hampton Roads to prepare for a voyage that would carry her around the world. Kentucky participated with the Second Squadron in Battle Plan No. 1 off Hampton Roads (23–26 August and 30 August–3 September) and the Southern Drill Grounds (26–29 August), thrust northward to Rockport (7–13 September), and shot at targets in Cape Cod Bay (13 September–4 October), and then (4–5 October) coaled at Provincetown. While maneuvering off Lambert Point near Hampton Roads the ship ran aground, and floated off by the next day (7–8 October). The grounding necessitated that she complete some last minute repairs at Norfolk and in dry dock at Boston (9 October–1 December and 3–7 December, respectively). The ship then called at Newport for additional crewmen and returned to Hampton Roads.

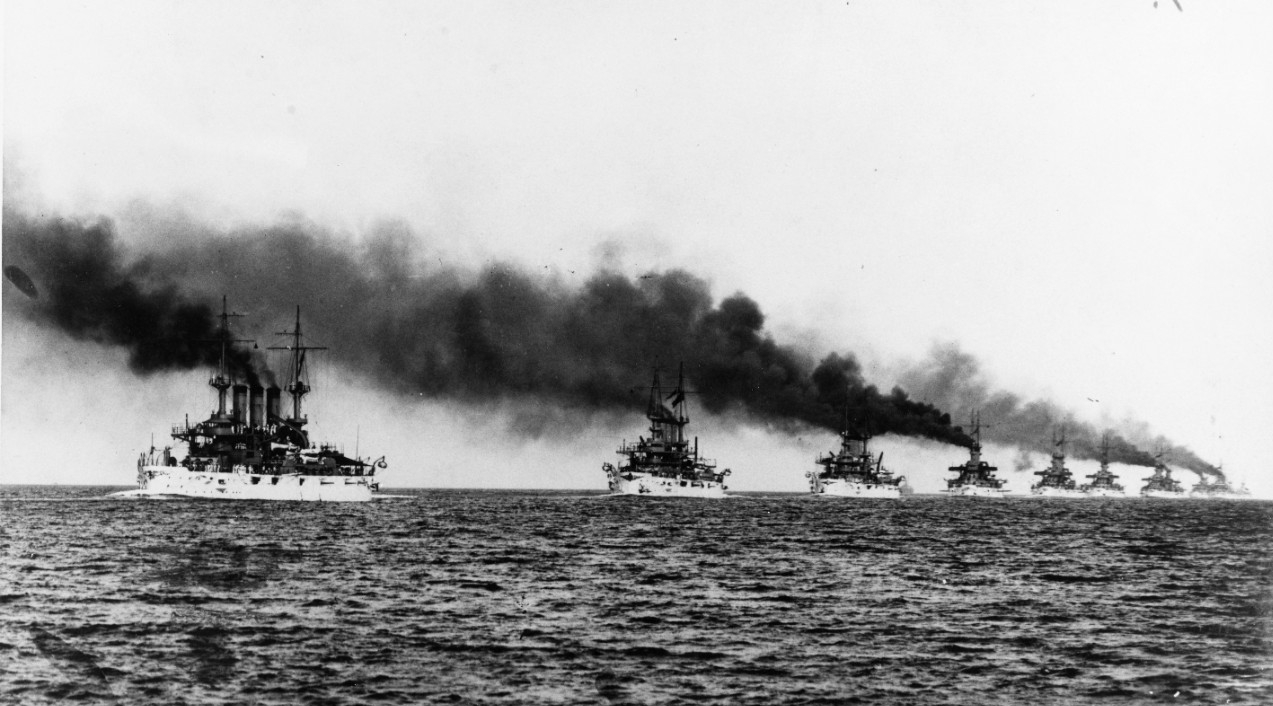

Kentucky sailed in the Second Squadron as one of the 16 battleships of the “Great White Fleet.” President Theodore Roosevelt dispatched the fleet on a global circumnavigation to serve as a deterrent to possible war in the Pacific; to raise U.S. prestige as a global naval power; and, most importantly, to impress upon Congress the need for a strong navy and a thriving merchant fleet to keep pace with the United States’ expanding international interests and far flung possessions. In addition, the President wanted to discover what condition the fleet would be in after such a transit, noting before the fleet sailed: “I want all failures, blunders and shortcomings to be made apparent in time of peace and not in time of war.” Rear Adm. Evans stated earlier that his ships put to sea “ready at the drop of a hat for a feast, a frolic or a fight.”

President Roosevelt reviewed the fleet on 16 December 1907, as Kentucky and Alabama, Connecticut (Battleship No. 18), Georgia (Battleship No. 15), Illinois, Kansas (Battleship No. 21), Kearsarge, Louisiana (Battleship No. 19), Maine, Minnesota (Battleship No. 22), Missouri (Battleship No. 11), New Jersey (Battleship No. 16), Ohio (Battleship No. 12), Rhode Island (Battleship No. 17), Vermont (Battleship No. 20), and Virginia (Battleship No. 13) steamed past presidential yacht Mayflower off Hampton Roads. Hopkins (Destroyer No. 6), Hull (Destroyer No. 7), Lawrence (Destroyer No. 8), Stewart (Destroyer No. 13), Truxtun (Destroyer No. 14), and Whipple (Destroyer No. 15) screened the battleships during the first leg of their journey to the west coast. The train vessels included gunboat Yankton -- a converted yacht -- repair ship Panther, supply vessel Culgoa, and refrigerator ship Glacier.

“Our ship held about 2,000 tons of the stuff,” a member of the ship’s company in Connecticut (Battleship No. 18) described coaling day. “All the deckhands would go down into the collier (coal supply ship) and fill these big bags with about 500 pounds. Then they'd hoist ‘em over to us down in the coal bunkers and we'd spread out the coal with shovels until all the bunkers -- about 20 -- were full to the top.”

The ships charted southerly courses and visited Port of Spain, Trinidad (23–29 December), crossed the equator on 6 January 1908, and anchored at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where a brawl between sailors from Louisiana (Battleship No. 19) and longshoremen marred the visit (12–22 January). Kentucky battled heavy wind and navigated through dense fog while passing through the Strait of Magellan, and visited Possession Bay (31 January–1 February) and Punta Arenas, Chile (1–7 February), and Callao, Peru (20–29 February). The Great White Fleet then carried out gunnery practice at Magdalena Bay, Baja California, Mexico (12 March–11 April).

Kentucky steamed with the fleet along the west coast and visited Californian ports: San Diego (14–18 April 1908); San Pedro (18–19 April); Redondo Beach (19–25 April); Santa Barbara (25–30 April); Monterey (1–4 May); Santa Cruz (4–5 May); and San Francisco (6–18 May). Rear Adm. Charles M. Thomas relieved Evans while the fleet put into San Francisco, and Rear Adm. Charles S. Sperry subsequently relieved Thomas. Kentucky meanwhile sailed in company with some of the ships and visited two ports in the State of Washington: Bremerton (21 May–3 June and 4–25 June) and Port Townsend (3–4 June). Kentucky returned to San Francisco on 28 June, where she celebrated Independence Day.

The voyage to the Pacific illustrated the tendency for Alabama and Maine to consume large quantities of coal, and consequently, when the bulk of the Fleet headed north to visit the Pacific Northwest, both ships remained behind while Alabama underwent repairs at Mare Island Navy Yard. Nebraska (Battleship No. 14) relieved Alabama, and Wisconsin (Battleship No. 9) relieved Maine. Alabama and Maine sailed from San Francisco on 8 June to complete their own, more direct, circumnavigation of the globe.

The Great White Fleet set out across the Pacific (7–16 July 1908). Kentucky visited Honolulu in the Hawaiian Islands (16–22 July), Auckland, New Zealand (9–15 August), and three Australian ports: Sydney (20–27 August); Melbourne (29 August–5 September); and Albany (11–18 September). A cholera epidemic prevented crewmen from going ashore when Kentucky and her consorts reached Manila, Philippines (2–10 October), but the sailors and marines received some consolation when their mail caught up with them.

The fleet made for Japanese waters but a typhoon slammed into the ships while they crossed the South China Sea. “The typhoon happened right off Formosa [Taiwan],” a sailor from one of the ships afterward recalled. “All you could see, when a ship was in trough, was the trunk of its mast above the wave tops. That was all you could see of an entire battleship. Then our turn would come to go into a trough, and we couldn't see anything for a while.”

Kentucky visited Yokohama (18–24 October 1908). She joined seven of the other battleships and visited Amoy (29 October–5 November), following which they returned to Philippine waters and called briefly (8–12 November) at Olongapo on Subic Bay. Kentucky and a number of the ships carried out target practice on the range in Manila Bay (12 November–1 December). The battleships finished shooting and rendezvoused with the rest of the fleet to continue the voyage across the Indian Ocean, and put into Colombo, Ceylon [Sri Lanka], where tea merchant and yachtsman Sir Thomas J. Lipton hosted the men with complimentary tea (13–20 December).

The ships turned northward into the Red Sea and made for the Suez Canal, and Kentucky reached Suez, Egypt (3–5 January 1909), passed through the canal, and visited Port Said (6–8 January). They then divided into different groups to visit ports across the Mediterranean. Kentucky cruised independently to Tripoli, the chief city of the Ottoman Turkish province of the same name [Libya] (12–14 January). Kentucky rendezvoused with Division 4 and they visited Algiers (18–30 January), and then Gibraltar while the ships assembled and reformed the fleet (1–6 February). The Great White Fleet crossed the Atlantic from Gibraltar and returned to the United States (6–22 February), where President Roosevelt reviewed the ships at Hampton Roads (22–26 February). Kentucky remained there until 8 March, when she entered Norfolk Navy Yard for a survey through 2 April. On 12 April Kentucky was placed in reserve at Philadelphia Navy Yard, and placed out of commission at Norfolk Navy Yard on 28 August 1909.

Three years later, Navy planners decided to recommission Kentucky in order to train Naval Militia. The ship correspondingly underwent a number of modifications, and was fitted with distinguishing cage masts, along with new water-tube boilers. Yard workers cut down her tophamper and installed simplified forebridges, and added shields to the 13-inch guns just inboard of their ports. By this point, the casemate 6-pounders had been removed, and further changes in her armament included mounting four additional 5-inch guns at the angles of the superstructure deck, so as to enable her to expand the arc of fire when fighting destroyers and lighter craft. Sixteen of the 20 6-pounder rapid-fire guns and all four of the 1-pounders were also removed. The changes in the ship’s batteries required the reconfiguration of their magazines. In an effort to reduce weight, the two forward boat cranes were also taken off. The battleship emerged from the yard painted grey in lieu of her previous white-and-buff scheme, and in combination with the other work presented a dramatically altered silhouette.

Kentucky was placed in commission in the 2nd Reserve at Norfolk on 4 June 1912, and on 1 July of that year in the 1st Reserve. The ship joined the Atlantic Reserve Fleet (3 August–8 October) and briefly (10–17 October 1912) steamed to the North River for a naval review by President Taft and Secretary of the Navy George von L. Meyer on the 14th, a voyage that included full-power and endurance runs. Kentucky did not otherwise operate at sea before being placed in ordinary at Philadelphia Navy Yard on 31 May 1913.

The battleship was re-commissioned at Philadelphia on 23 June 1915, and on 3 July set out to train New York Naval Militia and civilian volunteers on a cruise from Long Island to ports in New England and Chesapeake Bay. She disembarked the militiamen at New York and sailed to Portland to embark Maine militia for a training cruise, returning to Philadelphia on 31 August.

Revolution tore Mexico apart as disparate groups lunged vengefully at each other and Gen. Victoriano Huerta, one of the strongmen, ruthlessly eliminated rivals and ambitiously amassed power among the Federales (government troops). The chaos endangered Americans caught in the midst of the war and President Woodrow Wilson called on U.S. warships to protect, and if necessary, evacuate them.

Kentucky consequently sailed on 11 September for Mexican waters to protect Americans ashore in that country during the fighting. The ship reached Vera Cruz, Mexico, on 28 September 1915, and except for an opportunity to celebrate Mardi Gras at New Orleans, La., in March 1916, she patrolled off the Mexican coast until 2 June 1916. Afterward, Kentucky called at Guantánamo Bay and Santa Domingo en-route to Philadelphia, where she arrived on 18 June. Following maneuvers and tactics ranging north to Newport during the summer, Kentucky arrived in New York on 2 October and remained in the North River until the end of the year. She entered New York Navy Yard for repairs and an overhaul on 1 January 1917, and trained men of the New York and New Jersey Naval Militias.

Kentucky lay at New York when the United States entered World War I on 6 April 1917. The ship’s company numbered 21 officers and 207 enlisted men, augmented by five officers and six men of the Naval Coast Defense Reserve. In addition to their other duties, the officers served as inspector-instructors of New York and New Jersey Naval Militias. In addition, two officers were also detailed to duty in examining and enrolling applicants in the Naval Coast Defense Reserve. The Navy Department began to expand for the war and ordered all of the crew to receive intensive 5-inch gun drill preparatory to (possibly) assigning them as Navy Armed Guards for merchant vessels crossing the Atlantic in the face of deadly German U-boats. In addition, workers removed six of the 18 5-inch guns for installation in other ships. Kentucky wrapped-up her yard work, loaded provisions, and at 3:00 p.m. on 29 April left the navy yard and anchored off Tompkinsville.

At 5:00 p.m. on 1 May 1917, the battleship set out for Yorktown, Va., escorted by Monaghan (Destroyer No. 32) and Walke (Destroyer No. 34). The ships sailed under orders to stop at Hampton Roads for a 40-foot steamer to be delivered from Norfolk Navy Yard, which they received the following day, and resumed their voyage, anchoring off the York River at 6:00 p.m. on the 4th. Kentucky there learned that she was to work with other ships of Squadron 1 for training recruits for engineering duty and for Navy Armed Guard service. The ship’s deck compliment was reduced in order to accommodate 280 men for training, and 90 men of the ship’s company formed the nucleus for duty as instructors. The instructors underwent six weeks of intensive training. One half of the trainees were routinely transferred every three weeks, after which a new contingent of recruits reported on board, a cycle that the ship continued through the summer (6 May–12 August). Kentucky usually steamed during daylight for six days in the week for two weeks, and spent the third week coaling, completing repairs, and transferring the trainees.

These training cruises did not pass without incidents, however, and while the ship practiced firing on the quarterdeck on 24 May 1917, a Hotchkiss M1909 Benét-Mercié machine gun’s muzzle dropped, causing bullets to strike the water way. The rebound of the splinters from the rounds and pieces of steel of the water way wounded a number of men, who were then transferred to hospital ship Solace for treatment. As sailors hoisted the second steamer on 12 August, the falls carried away, allowing the steamer to drop into the water. The impact damaged the boat to such an extent that she sank, with all of the equipment on board, in barely three minutes. In addition, two more of her 5-inch guns were removed in July.

Kentucky sometimes broke-up the rigorous training schedule and she joined other battleships for maneuvers and battle practice (13–19 August 1917). The ship detached and anchored at Port Jefferson, N.Y., and there continued training men in engineering duties and in Long Island Sound until 30 September. She stood out to sea again for maneuvers with the fleet (1–6 October), anchored at York River, and then resumed training recruits while steaming in Chesapeake Bay through the end of the year, and two more 5-inch guns were removed in December 1917.

Early in the New Year in January 1918, the Fuel Administration of New England informed the Navy that the region’s ability to continue industries essential to the war effort hinged upon keeping the channel clear of ice from Baltimore, from which the principal shipments of coal would be made. Kentucky thus broke up the ice and released ships trapped in Baltimore’s harbor, enabling the coal shipments to New England to resume. Collier Achilles, a 19,585 ton civilian ship originally built to service ships operating in the Panama Canal Zone, became one of the first such vessels to reach Boston when she brought an emergency cargo of coal into that port on 17 January. The battleship returned to training men in February and March, and on 18 April completed an overhaul at Boston Navy Yard.

Kentucky continued to train recruits and at about 1:20 p.m. on 29 April 1918, Achilles collided with her while the two ships maneuvered in dense fog. The collier struck the battleship on her starboard side whale boat, which was rigged as a life boat, and also alongside the muzzle of No. 13 5-inch gun, damaging both the boat and the gun. The ships opened the range and neither reported casualties. Kentucky stood out of Hampton Roads in company with the battleships of Divisions 1 and 9 and a squadron of submarine chasers for southern waters (11 June–11 July 1918). The ships called at Charleston Navy Yard, S.C., on 13 June, on the 17th at Key West, Fla., and reached Pensacola on the 20th. Kentucky embarked a draft of 145 engineers, eight steersmen, and 23 2nd class seamen and turned her prow back to sea on 3 July. Two days later the submarine chasers detached for supplies at Key West, while Kentucky and continued the voyage, stopping again at Charleston (8–9 July) before returning with Division 1 and some submarine chasers to Hampton Roads. The ships present included Alabama, Illinois, Kearsarge, Maine, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin, Argentinean battleship Rivadavia, Columbia (Cruiser No. 12), Des Moines (Cruiser No. 15), and Neptune (Fuel Ship No. 8). British light cruiser Isis (N.61) and destroyer Sylph (F.68) were also present, having arrived from Halifax, Nova Scotia, on the 3rd, in time to help the Americans celebrate Independence Day. The increased aerial threat concerned naval planners and during the war Kentucky received two 3-inch antiaircraft guns.

Kentucky sailed with her consorts of Division 1 as they carried out gunnery training at Tangier Sound (16–20 July 1918) and then lay to in the York River. A diver went over the side and inspected a propeller, and discovered that the inboard propeller shaft had fractured and that only the coupling at the strut held the screw and the balance of the shaft. The ship nonetheless continued training in Chesapeake Bay until the 26th, when (26 July–1 August) she completed repairs in dry dock at Norfolk Navy Yard. The ship returned to her engineering training regimen in Chesapeake Bay, but again accomplished work in dry dock at Norfolk Navy Yard (26 October–5 November). Kentucky trained several thousand men for service in ships of the war-expanded Navy and was training her 15th group of recruits when she anchored in the York River on 8 November, and when, three days later, the rival powers signed the Armistice. The ship operated in Chesapeake Bay until 15 December, when she stood down the York River and shaped northerly courses for Boston Navy Yard, where she completed an overhaul (20 December 1918–18 March 1919).

Following that work, the aging ship rejoined the fleet and participated in maneuvers and exercises ranging north from Norfolk to New England waters. The voyage included celebrating the fifth bond issue supporting the Allied war effort during World War I, popularly known as the Victory Liberty Loan, which was released on 21 April 1919.

Kentucky then (7 June–27 August 1919) set out for the Naval Academy, where she embarked several hundred midshipmen for training in the West Indies. On 9 June the battlewagon took station in a column with Alabama, Illinois, Kearsarge, Maine, and Wisconsin as they charted courses into warmer climes. The squadron carried out refresher training out of Guantánamo Bay (16–22 June) and St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands (25 June–1 July). They turned westward, celebrated Independence Day at sea, and reached Colón at the Panama Canal on 5 July, and into the 7th passed through the canal to Balboa. Following the ships’ brief sojourn into the Pacific, they came about and returned through the Panama Canal into the Caribbean, and arrived back at Guantánamo Bay for another fleeing stop (12–17 July).

The battleships next sailed for New York, which they reached on the 26th, and some of the vessels continued on to Provincetown and then swung around for New York (28 July–8 August). On the 11th, Kentucky and her cohorts stood out of that bustling port for the Southern Drill Grounds, where she trained the midshipmen in gunnery practice, and the battlewagons wrapped-up their shooting and returned the midshipmen to the Naval Academy, where the men disembarked two days later. Kentucky proceeded to Philadelphia Navy Yard, and she was there placed out of commission on 29 May 1920. Workers removed five of her remaining eight 5-inch guns during this period.

While also at Philadelphia Kearsarge was converted to a crane ship and on 5 August 1920, renamed Crane Ship No. 1 (AB-1). The battlewagon received a large revolving crane with a rated lifting capacity of 250 tons, as well as ten foot wide hull blisters which gave her more stability. Navy planners also briefly considered converting Kentucky into such an auxiliary. On 22 May 1922, however, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels issued a directive to the Bureaus of Construction and Repair, Engineering, and Ordnance, stating that the “desirability of retaining the U.S.S. KENTUCKY for possible use for conversion into a crane ship similar to Crane Ship No. 1 (KEARSARGE) no longer existing, this vessel will be scrapped and disposed of in accordance with the rules for scrapping vessels now being formulated by the Board of which Admiral Taylor [Rear Adm. David W. Taylor, Chief, Bureau of Construction and Repair] is Senior Member.”

Kentucky was therefore stricken from the Navy Vessel Register and placed on the Sale List on 27 May 1922, and on 24 March 1923, sold to Dravo Construction Co., of Pittsburgh, Pa., for the sum of $103,500 in accordance with the Washington Naval Treaty limiting naval armaments. The Navy delivered the ship to the purchaser at 0025 on 25 April 1923, and at 0940 she left the yard for the breakers.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Capt. Colby M. Chester | 15 May 1900 |

| Capt. Charles H. Stockton | 3 March 1901 |

| Capt. Robert M. Berry | 13 March 1903 |

| Capt. William J. Barnette | 14 June 1904 |

| Capt. Edward B. Barry | 31 December 1905 |

| Capt. Walter C. Cowles | 1 November 1907 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Henry A. Wiley | 30 April 1909 |

| Capt. Benjamin Tappan | 9 June 1909 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Walter G. Roper | 4 June 1912 |

| Cmdr. Julian L. Latimer | 1 January 1914 |

| Cmdr. Douglas E. Dismukes | 22 July 1915 |

| Capt. Hilary H. Royall | 9 September 1917 |

| Capt. James P. Morton | 21 February 1918 |

| Cmdr. Bert B. Taylor | 11 December 1918 |

| Capt. William B. Wells | February 1919 |

Mark L. Evans and Paul J. Marcello

21 December 2017