Fanshaw Bay (CVE-70)

1943–1959

A bay indenting the coast on the eastern side of Frederick Sound in the Alexander Archipelago of Alaska.

(CVE-70: displacement 7,800; length 512'3"; beam 65'2"; extreme width 108'1"; draft 22'6"; speed 20 knots; complement 860; armament 1 5-inch, 16 40-millimeter, 20 20-millimeter; aircraft 28; class Casablanca; type S4-S2-BB3)

Fanshaw Bay was authorized under a Maritime Commission contract (M.C. Hull 316); subsequently classified as an aircraft escort vessel (AVG-70); reclassified to an auxiliary aircraft carrier (ACV-70) on 20 August 1942; laid down on 18 May 1943, by Kaiser Shipbuilding Co., at Vancouver, Wash.; reclassified to an escort aircraft carrier (CVE-70) on 15 July 1943; launched on 1 November 1943; and was sponsored by Mrs. Lorna V. Kenworthy, wife of Capt. Jesse L. Kenworthy Jr., an aviation pioneer and former executive officer of battleship Oklahoma (BB-37) when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, T.H., on 7 December 1941.

Fanshaw Bay was commissioned on 9 December 1943, at Astoria, Ore., Capt. Douglass P. Johnson in command, then loaded ammunition at Port Townsend, Wash., on 31 December, and worked up as she prepared for war, touching at various locations as she did so, including Port Angeles, Wash. (6–8 January 1944), and San Francisco, Calif. (11–16 January). Rear Adm. Gerald F. Bogan, Commander, Carrier Division (CarDiv) 25, broke his flag in the new warship during this period.

Planes jammed Fanshaw Bay’s crowded flight deck and hangar deck as she ferried Republic P-47 Thunderbolts, Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, and Douglas A-20 Havocs for the USAAF and slid beneath the Golden Gate Bridge on 16 January 1944. The escort carrier ferried the special cargo on what amounted to her shakedown cruise to Gladstone [Townsville], Australia, on 2 February 1944. She then came about for the return voyage to the U.S. via Brisbane, Australia (8–12 February), and Nouméa, New Caledonia (15–16 February).

While Fanshaw Bay completed voyage repairs and underwent maintenance at San Diego, Calif. (4 March—6 April 1944), Composite Squadron (VC) 4 trained nearby with 12 Eastern FM-2 Wildcats and nine Eastern TBM-1C Avengers as the squadron prepared to deploy with the ship—until orders switched the squadrons. Rear Adm. Bogan hoisted his flag in Fanshaw Bay as the carrier loaded 16 FM-2s and ten TBM-1C’s of VC-68, the squadron that deployed with her, and sailed from San Diego for Majuro in the Marshall Islands (6–20 April 1944), accompanied by the small seaplane tender Orca (AVP-49).

Flight operations, however, in every circumstance, always pose risks; Ens. Joseph J. Hennessy, USNR, of VC-68 crashed while flying a TBM-1C (BuNo 16858) on takeoff in 11 April, one day out of Pearl Harbor. The Avenger sank in about 90 seconds, but Ens. Hennessy and his two-man crew escaped and Orca picked them up, transferring them back to their own ship by breeches buoy. An hour before noon the next day [12 April], Fanshaw Bay launched her remaining planes to fly in to NAS Ford Island, then conducted gunnery practice. Fanshaw Bay recovered her aircraft and resumed the voyage, screened by escort ships John C. Butler (DE-339), Raymond (DE-341), and Richard M. Rowell (DE-403). Ten days of hunting Japanese submarines proved fruitless, and the ship returned to Pearl Harbor for replenishment and training.

Fanshaw Bay sailed on 29 May 1944 to join a vast assemblage of shipping at Eniwetok in the Marshalls staging for Operation Forager—landings in the Marianas Islands. During flight operations an FM-2 (BuNo 16093) of VC-68 crashed while taking off from the carrier on 30 May, and at 1000 on 8 June the ship lost another Wildcat (BuNo 46996), piloted by Ens. Lane, when it went over the side during carrier qualifications. The plane guard destroyer recovered Lane. A few minutes later on the busy day, another Wildcat (BuNo 16122) crashed into the barrier on landing. The pilot emerged from the fighter uninjured but the impact slightly damaged the plane. The warship set out with her consorts on 11 June, and operated initially about 30 miles east of Saipan. Fanshaw Bay launched Wildcats that flew combat air patrol (CAP), and fighters and bombers that flew antisubmarine patrols and photographic reconnaissance flights, as well as raids on Japanese positions to pave the way for the invasion on 15 June.

Forager penetrated the inner defensive perimeter of the Japanese “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” and triggered A-Go—an enemy counterattack that led to the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The Japanese intended for their shore-based planes to cripple U.S. air power in order to facilitate their carrier strikes—the ships were to refuel and rearm at Guam. Their fuel shortages and inadequate training, however, bedeviled A-Go, while U.S. signal decryption breakthroughs enabled attacks on enemy submarines that deprived the enemy of intelligence. Raids on the Bonin and Volcano Islands furthermore disrupted Japanese aerial staging en route to the Marianas, and their main attacks passed through U.S. antiaircraft fire to reach the carriers.

The Japanese struck back and at 1715 on 15 June 1944, the ship received a report of five planes heading toward her at high speed, 71 miles to the southeast. White Plains (CVE-66) launched four FM-2s of Fanshaw Bay’s old friends VC-4 as CAP, and controllers vectored them to intercept the attackers. The Wildcats intercepted the bombers at a range of 36 miles out from Fanshaw Bay and splashed three of them, and then turned and pursued the fourth, which was shot down within sight of the warship. Meanwhile, at 1809, Fanshaw Bay launched her own Wildcats into the fray, but the fifth attacker eluded all of the interceptors and fired a torpedo at Fanshaw Bay at 1812. Capt. Johnson ordered “full right rudder” and the ship heeled over sharply as the torpedo churned by. Lt. Crissie C. Sanders flew one of the ship’s Wildcats and splashed the determined bomber three minutes later.

The 17th of June 1944 proved a dark day in Fanshaw Bay’s history. Lt. (j.g.) Joseph W. Oberlin, USNR, AOM2c D. Albert Yoakum, USNR, and ARM2c George L. Keopp, USNR, of VC-68 launched in a TBM-1C (BuNo 16858). The Avenger cleared the catapult but climbed rapidly until it stalled and spun to port and crashed into the sea off the port bow, where it sank. Shortly after it sank a violent explosion erupted from the area, most likely because a depth charge detonated, killing the pilot and his two-man crew. Later that day, a TBM-1C (BuNo 45446) attempted a landing but crashed ahead of the ship. The plane guard rescued pilot and gunner, but the radioman sank with the aircraft.

In the late afternoon, Fanshaw Bay’s Combat Information Center (CIC) reported as many as 70 unidentified aircraft approaching from the southeast at a range of 40 miles. The ship sounded general quarters as pilots and crews scrambled to man their planes. In a few minutes, Fanshaw Bay launched 14 aircraft into the ether to join 32 planes from other carriers. Japanese planes fought their way through the CAP and desperately attacked the carriers from all sides, but the Wildcats tangled with the attackers while shipboard 20- and 40-millimeter guns added their firing to the cacophony. Fanshaw Bay’s fighters claimed one of the enemy planes, and her guns splashed as many as three more, and claimed two damaged.

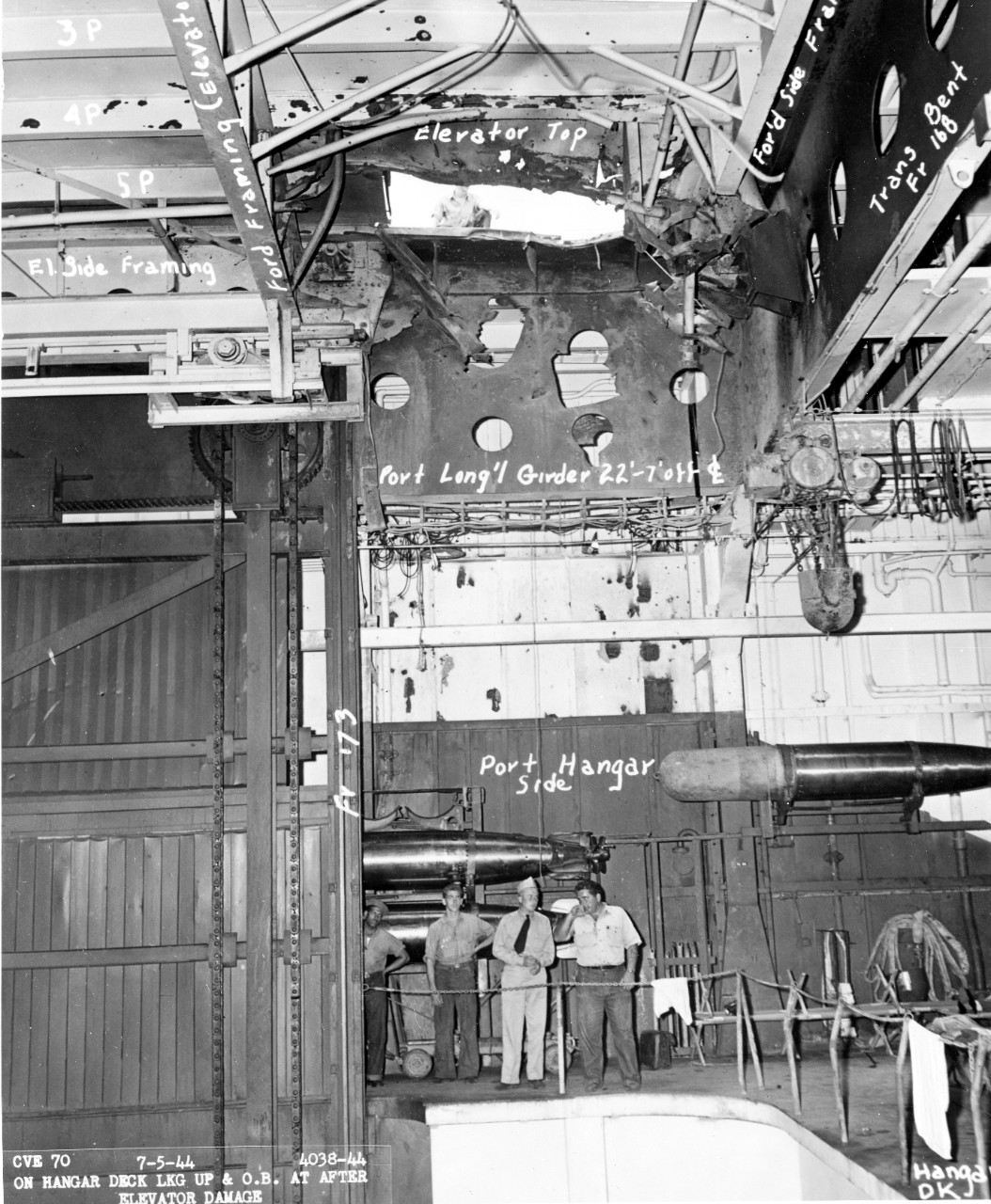

The Japanese persevered, however, with deadly determination, and at 1852 an enemy plane made a run on Fanshaw Bay and dropped a bomb from approximately 1,500 feet, as the carrier steamed near 15°00'N, 145°00'E. The enemy ordnance penetrated into the corner of the after elevator and crashed through the thin decks, showering fragments into shattered compartments, rupturing a fire main, and severing electrical cables. Multiple fires blazed up, the ship took on a severe list to port, and she settled six feet by the stern; to enable him to continue to exercise command, Rear Adm. Bogan, accompanied by his staff, transferred his flag to the destroyer Porterfield (DD-682). The inferno compelled the ship’s planes to attempt to land on board other carriers. Three VC-68 Wildcats (BuNos 16710 and 46858), and one flown by Lt. Daniel H. Stinemetz (BuNo 45446), crashed during the ensuing turmoil or in battle against the Japanese, but nearby destroyers rescued the shaken men from their life rafts.

All hands turned to and damage control teams brought the flames under control in just under an hour. Many of the men nonetheless stood waist deep in the water as they fought through the night to save the ship, and spent many hours laboriously extinguishing the flames, pumping out the water, and repairing the damage to enable Fanshaw Bay to resume operations under her own steam. The attack killed 14 men and wounded 23, however, and at 1130 on the 18th, the ship’s company sadly consigned their fallen shipmates to the deep. The battered ship came about and sailed for Pearl Harbor and battle damage repairs. Flight operations, with their attendant hazards, continued; Lt. Pierce D. Mooney, USNR, died when the Avenger (BuNo 16925) he was piloting from the carrier crashed on 29 June.

Rear Adm. Clifton A.F. Sprague, Commander, CarDiv 25, broke his flag in Fanshaw Bay as the newly repaired ship charted a course for Manus in the Admiralties, where she arrived on 28 August 1944. That day Ens. William J. Johnston, USNR, crashed in a Wildcat (BuNo 46894) while taking off from the carrier. Fanshaw Bay operated alongside five other escort carriers and eight destroyers in Task Group (TG) 77.1, Rear Adm. Thomas L. Sprague in command, as she prepared to take part in Operation Tradewind—landings by the 41st Infantry Regiment (Reinforced), Maj. Gen. John C. Persons, USA, on Morotai, in the Molucca Islands of the Netherlands East Indies [Indonesia]. The men of VC-68 needed a respite from the war and Fanshaw Bay switched squadrons as VC-66 boarded the ship. The increasingly seasoned carrier stood out to sea on 10 September and turned her prow toward Morotai.

The weather was calm and clear on 15 September 1944, the sea smooth, wind light from the south, the moon reached its last quarter just above the eastern horizon, and the visibility was 4,000–5,000 yards. Light cruiser Phoenix (CL-46) served in TG 77.2, Rear Adm. Russell S. Berkey, Commander, Cruiser Division 15, and approached her fire support area in the Galela area by using radar until the sun rose and it became light enough to take bearings and navigation from the open bridge. The target area became clearly discernable, especially the prominent outlines of volcanoes. While Phoenix and the other bombardment ships blasted the Japanese troops, planes from six escort carriers of Rear Adm. Thomas Sprague’s TG 77.1, screened by eight destroyers, also pounded enemy positions.

Later that day, on 16 September 1944 Fanshaw Bay’s pilots provided cover for Ens. Harold A. Thompson, USNR, from VF-26 in Suwanee, who had been shot down in Wasile Bay. Diving low, Fanshaw Bay’s planes bombed and strafed Japanese gun positions, as well as destroyed one Sally and two fighters identified as Mitsubishi A6M3 Hamps or A6M5 Zekes on the ground. Two Morotai-based motor torpedo boats, PT-363 and PT-489, commanded by Lt. Arthur M. Preston, Commander, Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron (MTBRon) 33, dashed in to snatch him out from under enemy gunfire from ashore. While the planes laid smoke, the PTs approached within 50 feet of the Japanese shore and recovered Ens. Thompson. Clifton Sprague later praised those who had taken part in the heroic operation: “The story of rescue of the Suwanee pilot consummated yesterday is one of outstanding heroism on part of PT boats. The pilots engaged deserve high praise, too…” Lt. Preston later received the Medal of Honor.

Tragically, the next day on 17 September 1944, Lt. (j.g.) Francis J. M. McCabe, USNR, AMM2c Robert L. Keough, USNR, and AMM2c Hyrum L. Shaffer, USNR, took off in an Avenger (BuNo 45869), and rendezvoused with a flight echelon of several other Avengers for an antisubmarine patrol about a mile offshore and at an altitude of 2,500 feet. As McCabe eased into the third position in the formation, he pulled up into position where Ens. Robert E. Holley, USNR, ARM2c Roger L. Plouffe, USNR, and ACM3c Manuel V. Calderon, USNR, was flying in BuNo 45959 and the two planes collided. White smoke filled Holley’s cockpit and both of the Avengers crashed. Holley bailed out but his parachute became entangled in the plane’s tail, and of the six men only Plouffe survived—he jumped and the submarine chaser PC-1134 pulled him from the water.

On 19 September 1944, Lt. (j.g.) Reynold Rodriquez, A-V(N), USNR, flying CAP, piloting an FM-2 (BuNo 16349), dove on a Hamp from an altitude of 1,000 feet, but he failed to pull out of his dive and plunged into the water, exploding on contact. Soon thereafter, Lt. (j.g.) George W. Brown, A-V(N), USNR, attacked the same Hamp that had eluded his squadron-mate and shot it down, the Mitsubishi crashing in flames.

The Allies used airfields on Morotai to support their operations against Japanese forces in the Philippines. Two Wildcats (BuNos 16380 and 46933) and an Avenger (BuNo 16947) crashed while Fanshaw Bay steamed toward Manus on 25 September. Two days later, Lt. Nelson R. Charles, USNR, crashed in an Avenger (BuNo 46318) but survived the wreck. The escort carrier replenished there (7–12 October), and then stood out for the invasion of Leyte in the Philippines.

While the ship steamed en route to Leyte Gulf on 16 October 1944, Lt. Jack R. Flint, USNR, of VC-68 manned an Avenger (BuNo 73394) during a patrol but wrecked while landing on board. The pilot, making his approach, overshot the ramp slightly. In trying to line up correctly, he started to settle at the ramp. The landing signal officer (LSO) gave him a low signal, and, as precious seconds ticked by and the aircraft continued to approach off center, a more exaggerated low signal, pounding the flight deck with his paddles. The pilot gave a burst of throttle and the LSO, believing that Flint would not be able to clear the deck waved him off. The pilot sheered slightly to port and the tail hook slipped over three arresting cables and caught the fourth line. The Avenger skidded sharply over the port side of the ship and hung there precariously, until salvage and recovery sailors cleared the deck. Flint sustained minor injuries but survived, and the aircraft incurred damage to the engine, propeller, port wing, bomb bay, and hydraulic lines in the landing gear and flap section.

Adm. William F. Halsey Jr., Commander, Third Fleet, led nine fleet and eight small carriers into those troubled waters. Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid, Commander, Seventh Fleet, led a force that included TG 77.4, Rear Adm. Thomas Sprague—consisting of 18 escort carriers organized in Task Units (TUs) 77.4.1, 77.4.2, and 77.4.3, and known by their voice radio calls as Taffys 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Chenango (CVE-28), Petrof Bay (CVE-80), Saginaw Bay (CVE-82), Sangamon (CVE-26), Santee (CVE-29), and Suwanee (CVE-27) and their screens formed Taffy 1, Rear Adm. Thomas Sprague, and fought off northern Mindanao. Chenango and Saginaw Bay swung around on the 24th to carry planes to Morotai in the Netherlands East Indies for repairs and overhaul. Kadashan Bay (CVE-76), Manila Bay, Marcus Island (CVE-77), Natoma Bay, Ommaney Bay (CVE-79), and Savo Island (CVE-78) of Taffy 2, Rear Adm. Felix B. Stump, operated off the entrance to Leyte Gulf.

Fanshaw Bay steamed with the two CarDivs of Taffy 3, Rear Adm. Clifton A. F. Sprague, off Samar. Kalinin Bay (CVE-68), St. Lo (CVE-63), and White Plains formed CarDiv 25, Rear Adm. Clifton Sprague, while Gambier Bay (CVE-73) and Kitkun Bay (CVE- 71) comprised CarDiv 26, Rear Adm. Ralph A. Ofstie. Destroyers Heermann (DD-523), Hoel (DD-533), and Johnston (DD-557), together with Dennis (DE-405), John C. Butler, Raymond, and Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413), screened Taffy 3.

Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher meanwhile (October 1944) took Task Force (TF) 38 and struck Japanese reinforcement staging areas in the opening blow of the campaign to liberate Leyte. Aircraft from 17 carriers bombed airfields on Okinawa and other islands of the Ryūkyūs and sank 29 vessels on 10 October. The following day, planes pounded airfields on northern Luzon in preparation for raids on the Japanese bastion of Formosa [Taiwan]. From 12 to 14 October 1944 the force attacked ships, aerodromes, and industrial plants on Formosa and the Pescadores [Penghu] Islands and sank 22 vessels. Destroying Japanese air power on Formosa paved the way on 14 and 16 October for USAAF Boeing B-29 Superfortress raids on aircraft plant and airfield facilities on the island. On 14 October, the carriers launched a second raid on northern Luzon, and the following day a sweep over the Manila area. These strikes in total destroyed an estimated 438 Japanese aircraft in the air and 366 on the ground and, in combination with other battles, effectively cleared the skies for the landings on Leyte.

The Army’s Sixth Ranger Battalion landed on Dinagat and Suluan Islands at the entrance to Leyte Gulf to destroy Japanese installations capable of providing early warning of a U.S. attack, on 17 October 1944. The garrison on Suluan, however, managed to transmit an alert that prompted Adm. Toyoda Soemu, the Japanese Commander in Chief Combined Fleet, to order Shō-Gō 1—the defense of the Philippines.

While the Japanese marshalled their naval and air forces, U.S. troops landed on Leyte. Fanshaw Bay and the other escort carriers launched multiple air strikes that claimed 38 Japanese planes and damaged 28 more in the air and on the ground in attacks on Cebu, Negros, and Panay (18–19 October). Fanshaw Bay and her consorts then steamed off Samar (20–25 October) as they hurled their aircraft against the enemy to support the troops while they fought their way ashore and then moved inland. In addition, the ship launched CAP, antisubmarine patrols, observation flights, and drops of psychological warfare material. At 0928 on 22 October, Lt. (j.g.) John R.W. Landry, USNR, crashed into the barrier while landing, the Wildcat (BuNo 56860) turning over, demolishing it. Landry suffered serious, but fortunately not fatal, injuries.

Tension grew daily as rumors circulated as to the whereabouts of the Japanese fleet and on 22 October 1944, a succession of distinct fleet engagements, began when Shō-Gō 1 attempted to disrupt the U.S. landings off Leyte. Japanese fuel shortages compelled them to disperse their fleet into the Northern (a decoy), Central, and Southern Forces and they converged separately on Leyte Gulf. Attrition had reduced the Northern Force’s 1st Mobile Force, their principal naval aviation command and led by Vice Adm. Ozawa Jisaburō, to carrier Zuikaku and small carriers Chitose, Chiyōda, and Zuihō. Submarine Darter (SS-227) detected a group of Japanese warships northwest of Borneo on the 22nd and into the following day shadowed them. Bream (SS-243) meanwhile torpedoed heavy cruiser Aoba off Manila Bay, and Darter and Dace (SS-247) attacked what turned out to be the Japanese Center Force, Vice Adm. Kurita Takeo in command. Dace sank heavy cruiser Maya, and Darter sank heavy cruiser Atago and damaged her sister ship Takao, which came about for Brunei.

Enemy strikes also grew as Japanese planes repeatedly attacked the U.S. ships, however, and Fanshaw Bay often launched Wildcats that flew CAP over the anchored transports. The Japanese counterattacked more than once and on the 24th of October, a formation of bombers escorted by fighters suddenly came out of the sun and winged toward transports off Leyte. Four Wildcats flying from the ship shielded the vulnerable troopships as they intercepted and splashed five of eight Japanese fighters in one of the flights. Fanshaw Bay, however, recorded the loss of two Avengers (BuNos 46429 and 73320) of VC-68 on the 24th.

The planes of TG 38.2, TG 38.3, and TG 38.4 attacked Kurita as his ships crossed the Sibuyan Sea. Aircraft carriers Enterprise (CV-6), Intrepid (CV-11), Franklin (CV-13), and small aircraft carrier Cabot (CVL-28) launched strikes that sank battleship Musashi south of Luzon. Aircraft from the three task groups also damaged battleships Yamato and Nagato, heavy cruiser Tone, and destroyers Fujinami, Kiyoshimo, and Uranami.

U.S. planes furthermore attacked the Southern Force as it proceeded through the Sulu Sea, and sank destroyer Wakaba and damaged battleships Fusō and Yamashiro. Allied planes, motor torpedo boats, and destroyers attacked and turned back the Southern Force as the ships continued through the Sulu Sea into Surigao Strait. Japanese and friendly fire damaged Albert W. Grant (DD-649) but the Allies sank Fusō and Yamashiro, light cruiser Abukuma, and destroyers Asagumo, Michisio, Wakaba, and Yamagumo. Destroyer Akebono later scuttled Mogami. Ozawa in the meanwhile decoyed Halsey’s Third Fleet northward, but Halsey’s aircraft subsequently sank all four Japanese carriers, Chitose with the assistance of cruiser gunfire, off Cape Engaño. Halsey’s rapid thrust, however, carried his ships beyond range to protect the escort carriers of Taffy 3.

Occasional rain squalls swept through the area as Wednesday, 25 October 1944, dawned. The visibility gradually opened to approximately 40,000 yards with a low overcast, with the wind from the north-northwest. Fanshaw Bay and the other ships of Taffy 3 greeted the day preparing to launch strikes against the withdrawing Japanese ships of the Southern Force, or to support the troops fighting ashore. The carriers launched their first planes at dawn to head toward the retiring enemy ships. They armed their remaining aircraft with light bombs and rockets to attack Japanese troops and positions, or depth charges for those intended to fly antisubmarine patrols. Lt. (j.g.) Charles G. Feist, USNR, took off from Fanshaw Bay in a TBM-1C with Capt. Grant F. Cloud, AUS, from the Army’s 44th Tank Battalion, as an airborne observer, to patrol over the battlefields ashore and attack targets of opportunity.

Unbeknownst to the men of Taffy 3, however, the surviving warships of the Japanese Center Force, which included battleships Yamato, Haruna, Kongō, and Nagato, heavy cruisers Chikuma, Chōkai, Haguro, Kumano, Suzuya, and Tone, light cruisers Noshiro and Yahagi, and 11 destroyers, made a night passage through San Bernardino Strait into the Philippine Sea.

Fanshaw Bay finished launching her first strike group, and counted just 12 lightly armed planes still on board, when the CIC reported intercepting Japanese voice radio transmissions, indicating strong enemy forces in the area. Ens. William C. Brooks, Jr., USNR, of Pasadena, Calif., flying a VC-65 TBM-1C from St. Lo, sighted the “pagoda” masts of some of the Japanese ships at 0637 on 25 October 1944. Brooks radioed his sighting and then again and again attacked the enemy vessels, feats of extraordinary heroism for which he later received the Navy Cross.

Lookouts on board the ships of Taffy 3 could see bursts of Japanese antiaircraft fire on the northern horizon as the enemy vessels fired at Brooks’ plane and some additional Avengers, and within minutes, ships began to detect the approaching Japanese vessels on their radar. The Japanese surprised the Americans and caught Taffy 3 unprepared to face such a powerful onslaught, and the battle almost immediately became a precipitate flight in the face of the overwhelming enemy force. Sprague ordered his ships to come about to 090° at 0650, and flee to the eastward, hoping that a rain squall would cloak their escape. Taffy 3 urgently called for help, the carriers scrambled to launch their planes, and the escorts steamed to what quickly became the rear of the formation to lay protective smoke screens.

Fanshaw Bay launched her remaining 12 planes but at 0658, barely six minutes after the last of her planes flew off, the leading Japanese cruisers opened fire from an estimated range of 29,200 yards. The enemy ships scented prey and fired multiple salvoes that began to creep toward Fanshaw Bay’s stern as Capt. Johnson took evasive action. As the Japanese closed the range just after 0703, a providential rain squall reduced the visibility to barely half a mile. The destroyers emerged from the squall in all too brief a time and received orders to make a torpedo attack on the enemy battle line. Despite the escorts’ gallant efforts, the enemy closed the range.

By 0759 on 25 October 1944, the Japanese cruisers began to straddle Fanshaw Bay with their salvoes, and one large caliber shell passed through the carrier’s thin plating without exploding. About this time lookouts sighted what appeared to be a plane drop a 500-pound bomb on the stern of a Kongō class battleship—most likely an Avenger that damaged Kumano or Suzuya. Word spread quickly through Fanshaw Bay and many of the men cheered. The enemy continued to hurl salvo after salvo at the ship, however, and several rounds punched into her. By 0855, when she took the third hit, she was under fire from two cruisers and two destroyers, later joined by a third destroyer, though she maneuvered out of the way from the latter’s torpedo attack. The enemy nonetheless closed the range to 11,000 yards and a cruiser scored another hit on the flight deck. Fanshaw Bay’s damage control party struggled to control the fires as the ship burned from the shell hits.

Japanese gunfire blasted the U.S. ships as the escorts fought courageously against the seemingly hopeless odds, and planes flew repeated runs against the enemy vessels, some of them dummy runs without weapons to distract enemy fire. Ens. Robert B. Evans, USNR, one of the ship’s pilots, had served in the British Royal Air Force before transferring into the U.S. Naval Reserve. Evans repeatedly strafed the Japanese ships until he expended all of his ammunition, and then made dummy runs, and survived to receive the Distinguished Flying Cross for his extraordinary heroism. Lt. (j.g.) Thomas J. Lupo, USNR, of New Orleans, La., piloted an Avenger through heavy Japanese fire and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Lt. Cmdr. Richard S. Rogers and Lt. William J. Sloan of Alexandria, Ind., flew Avengers from the ship and each received a Gold Star in lieu of their second award of the Distinguished Flying Cross. Lt. (j.g.) William A. McCormick, USNR, and Lt. (j.g.) Joseph W. Oberlin, USNR, were also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. The valiant rearguard efforts threw Kurita’s ships into disarray and compelled his retirement despite the Japanese superiority in weight and firepower.

At about that time, Lt. (j.g.) Edwin C. Callan, USNR, of VC-65, returning to St. Lo after what had been a routine ASP over Leyte Gulf, sighted three Nakajima Ki.43 army fighters (Oscars) about 30 miles east of Leyte. Unnoticed by the trio, Callan prepared a message drop and flew toward Fanshaw Bay, only to soon find himself under attack by four Oscars, whose pilots raked the TBM-1C’s fuselage with 7.7-millimeter fire, one bullet grazing the head of AMM2c Floyd B. Wright, USNR, his turret gunner, over one of his eyes. Nevertheless, Wright stayed at his gun and returned the Japanese’ fire while Lt. (j.g.) Callan, despite badly damaged control cables, employed every evasive maneuver he knew as he descended toward the wavetops, skidding and jinking and managing to reach safety under the umbrella of friendly AA fire and safety on board his own ship.

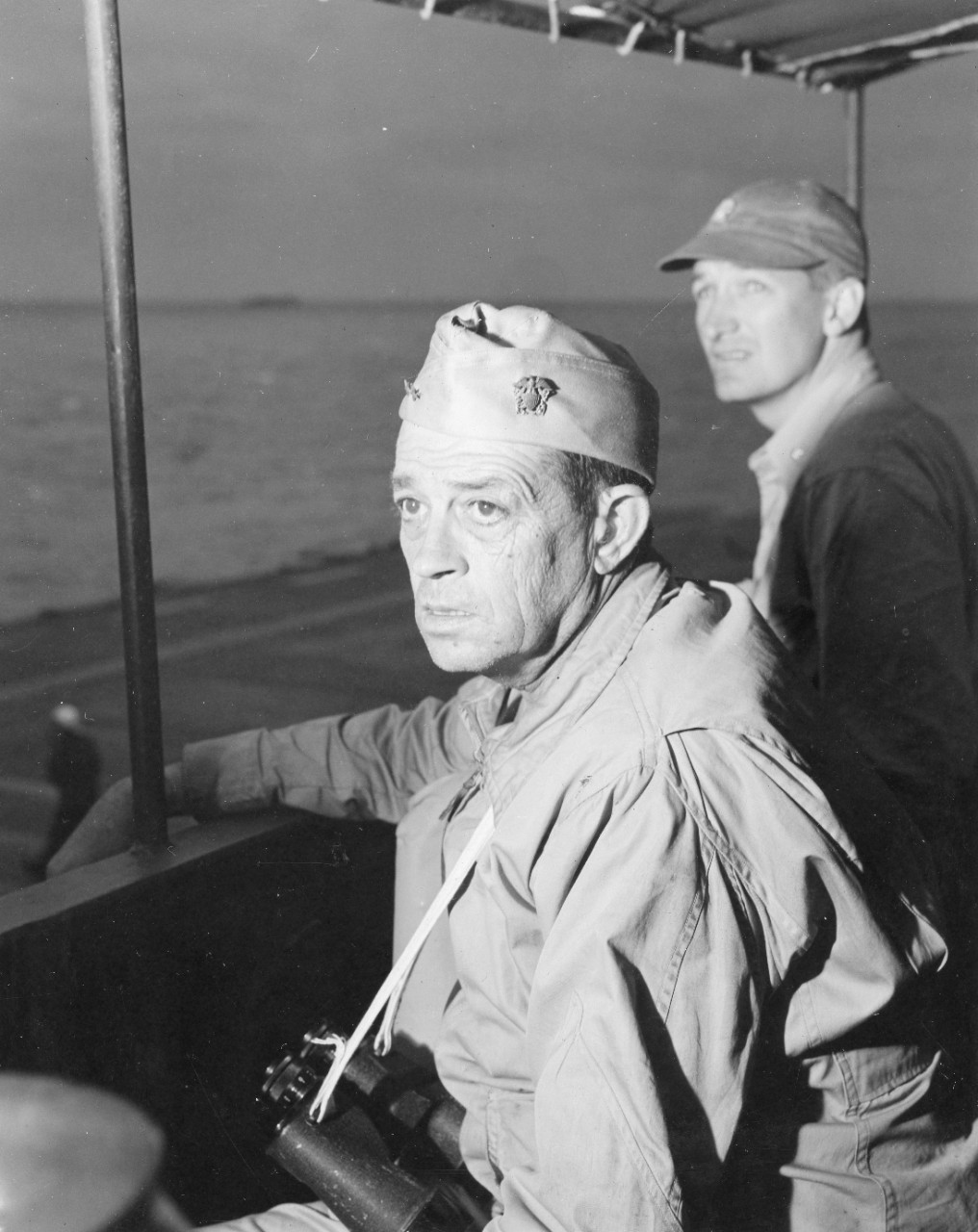

“At 0925 my mind was occupied with dodging torpedoes,” Sprague reflected afterward, “when near the bridge I heard one of the signalmen yell ‘They're getting away!’ I could hardly believe my eyes, but it looked as if the whole Japanese fleet was indeed retiring. However, it took a whole series of reports from circling planes to convince me. And still I could not get the fact to soak into my battle-numbed brain. At best, I had expected to be swimming by this time.”

Sprague received the Navy Cross for his “courage and determination” while in command during the battle in “the face of overwhelming enemy fire power and speed.” The admiral “so skillfully maneuvered his force that only two his carriers were lost. His stubborn defense and damage inflicted on the enemy ships by ships and aircraft of his command was a major factor contributing to the Japanese decision to retire…”

Fanshaw Bay lost Lt. Leonard D. Peterson, USNR, Y2c Gerald G. Doenges, Sea1c Charles A. Ledford, and AMM2c Edward G. Thrasher killed in action, while Lt. Cmdr. Edward W. Nester, Jr., Ens. Edward D. McDonald, USNR, and GM3c Harry A. Eorlatti, USNR, suffered wounds in action (those three wounded being transferred off the ship for further treatment ashore), while Sea1c Kenneth F. Leonhardt, USNR,, had been wounded, too, but the nature of his wounds permitted his retention on board after the battle. In addition, Fanshaw Bay lost four Wildcats (BuNos 55366, 55496, 55508, and 55578) in the air or on board the ship herself, as well as an Avenger (BuNo 73449). Four U.S. ships, valiantly fighting to the end, went down: Gambier Bay, Hoel; Johnston; and Samuel B. Roberts. In addition, Japanese gunfire damaged Kalinin Bay, Heermann, and Dennis, and straddled Kitkun Bay, St. Lo, and White Plains but scored no direct hits.

In the Battle off Samar and the Japanese retirement, U.S. forces damaged Yamato, Kongō, Chikuma, Chōkai, Haguro, Kumano, Suzuya, and Tone. Chikuma, Chōkai, and Suzuya suffered repeated explosions and fires and destroyers Nowaki, Fujinami, and Okinami, respectively, scuttled the cruisers with torpedoes—though Nowaki may have reached the area after U.S. aircraft delivered the coup de grâce to Chikuma. About 60 planes from TGs 38.2 and 38.4 tore into the retiring Japanese and sank Noshiro on the 26th. That day U.S. cruisers also crippled Nowaki with gunfire, and Owen (DD-536) sank her about 65 miles south-southeast of Legaspi, Luzon. The casualties the Japanese surface fleet sustained and its withdrawal to anchorages because of a lack of fuel finished it as an effective fighting force. Following Taffy 3’s ordeal off Samar, however, Japanese kamikazes pressed home suicidal attacks on the CVEs, sinking St. Lo and damaging Kalinin Bay and Kitkun Bay.

With her screen detached to rescue St. Lo’s survivors, Fanshaw Bay shaped a course for Manus, unprotected, and throughout the day landed planes from the other carriers that had fallen victim to the enemy’s sudden onslaught. The ship lost one of her Wildcats (BuNo 55419) the following day on the 26th, along with Ens. Schumann and the Avenger (BuNo 73429) he was flying. The searchers failed to recover Schumann. Fanshaw Bay replenished at Manus (1–7 November 1944), then returned via Pearl Harbor to San Diego for battle damage repairs. Lt. Cmdr. Scott S. Rogers, USNR, went down in a Wildcat (BuNo 56810) while the ship steamed toward Hawaiian waters on 9 November, but was recovered.

The ship next accomplished refresher training and patrol duty in Hawaiian waters. Lt. (j.g.) F.S. Bryant, USNR, and Ens. L.L. Ziegler, USNR, of VC-98 crashed in an Avenger (BuNo 16882) while training with the carrier on 21 February 1945. Both men sustained minor injuries but survived the nearly lethal trial. Lt. (j.g.) Ward J. Taylor of VC-99 wrecked in one of the versatile torpedo bombers (BuNo 23649) two days later but also emerged from the wreck. Fanshaw Bay turned toward Ulithi in the Caroline Islands. Ens. Roderick J. Sutton of VOC-2 crashed in an FM-2 Wildcat (BuNo 74214) while the ship made for Ulithi on 3 March 1945, though he was saved from the wreck. The ship steamed in company with Convoy PB-316T to the atoll (2–9 March).

During the tedious hours deployed across the far-flung reaches of the Pacific, the crew held basketball games in the hangar deck, fought boxing matches, played cards, and competed in pie-eating contests. “Happy Hour” consisted of a series of musical and comedy shows in which crewmen tried their hand at entertaining their homesick audience.

Fanshaw Bay re-embarked Adm. Clifton Sprague, who hoisted his flag as Commander, CarDiv 26. She switched out her squadrons again, and embarked Composite Spotting Squadron (VOC) 2. On 21 March 1945, she sortied for Operation Iceberg—the invasion of Okinawa in the Ryūkyū Islands. Four days later her planes began pre-invasion attacks on the Japanese troops on the island. Ens. Merrill W. Buckner crashed in a Wildcat (BuNo 74209) while flying over Kazan Rettō [the Volcano Islands] that busy day. Three days later on the 28th, another Wildcat (BuNo 74065) flying from the ship went down. Fanshaw Bay supported the landings on 1 April, and her planes flew ground support strikes, blasting enemy tanks, trucks, gun emplacements, and soldiers. Lt. (j.g.) A.W. Jones disappeared while flying a Wildcat (BuNo 73987) over Okinawa on 6 April, but the searchers failed to locate either his plane or the pilot.

The ship fought on the line continuously for 69 grueling days, and the aircraft of VOC-2 flew 2,089 sorties from her flight deck, the pilots averaging 91 hours of combat flying per month. The carrier’s FM-2s claimed to splash five Japanese planes in total, and their close air support missions contributed greatly to reducing the casualties of the U.S. soldiers and marines who fought their bloody way across the island.

The Japanese struck back fiercely, however, and repeatedly launched kamikaze suicide plane attacks against the Allied ships operating offshore. On 6 April 1945, they began the first of a series of ten mass kamikaze raids, interspersed with smaller attacks and named Kikusui (Floating Chrysanthemum) No. 1. These attacks involved an estimated 1,465 aircraft through 28 May.

The veteran warship fought off the kamikazes and continued daily operations in support of the advance of troops on the island. The relentless tempo ground down Fanshaw Bay as she witnessed the loss of plane after plane. Lt. Lewis W. Gaskill, USNR, of VOC-2 crashed in a Wildcat (BuNo 73875) while flying over Okinawa on 7 April 1945, but was saved from the clutches of the enemy. Lt. Clellan B. McAfee, USNR, crashed in a fighter (BuNo 74261) over the embattled island on the 11th but also survived the ordeal.

The ship’s good fortune at recovering her downed aviators did not last, however, and Lt. Warren L. McNett, USNR, disappeared while flying a Wildcat (BuNo 74401) over Okinawa on 28 April. On 4 May, Ens. John C. Hyde, USNR, failed to return while flying a mission in an Eastern FM-2 (BuNo 73884) over the fighting for Okinawa. Lt. (j.g.) Bernard F. McDermott, USNR, survived a crash in a Wildcat (BuNo 74156) on 16 May. Two days later, Lt. Richard F. Fletcher, USNR, disappeared while flying a Wildcat (BuNo 73836) over Okinawa, as did Lt. (j.g.) J. R. Mallard in an Avenger (BuNo 23601). Lt. Irving M. Applebaum crashed in his Wildcat (BuNo 73585) on 23 May but was rescued. Bagley (DD-386) escorted Fanshaw Bay on the 24th as the carrier continued the brisk tempo, but the destroyer’s No. 1 main generator failed and she came about for repairs in the Philippines. Fanshaw Bay finally turned from the strenuous campaign and on 28 May reached San Pedro Bay at the northwest end of Leyte Gulf to replenish. Between 9 June and 27 June, she sailed off Sakishima-Guntō, an archipelago that stretches to the southwest of the Ryūkyūs, to launch air strikes. An Avenger (BuNo 68790) of VOC-2 flying from the ship went down near Miyako-Jima [Miyako Island] on the 14th.

The following month found Fanshaw Bay taking part in a highly secret minesweeping operation that thrust into the heart of the remaining Japanese empire. TF 39, Rear Adm. Alexander Sharp, comprising seven light minelayers, 52 minesweepers, six high speed minesweepers, 49 motor minesweepers, and seven netlayers, began minesweeping operations in the East China Sea on 5 July 1945. On the 13th, TF 95, Rear Adm. Francis S. Low, consisting of large cruisers Alaska (CB-1) and Guam (CB-2), four light cruisers, and nine destroyers, set out from Leyte Gulf and carried out sweeps against Japanese vessels in that sea. Meanwhile, Fanshaw Bay and the other three escort carriers of TF 32, Rear Adm. Jesse B. Oldendorf, covered the minesweeping operations. Japanese planes and submarines harassed the Americans more than once during the foray into the contested waters. The carriers launched planes on strikes on shipping off the mouth of the Yangtze River on the 28th, but failed to find worthwhile targets. Two days later, Sharp completed the minesweeping, after the ships swept nearly 7,300 square miles and destroyed 404 mines—without losing a vessel.

Fanshaw Bay returned to Buckner Bay, Okinawa, but enemy submarines and kamikazes repeatedly attacked the vessels gathered offshore in desperate attempts to break-up the impending invasion of the Japanese home islands. The attackers failed to hit the warship, despite pressing home their assaults to the very mouth of the bay.

The carrier came about to the southeastward and called at Guam and Eniwetok to load aircraft and replenish. Fanshaw Bay also loaded foul weather gear, for she received orders to turn northward and serve under Vice Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher, Commander, Ninth Fleet, and Alaskan Sea Frontier. Her historian observed that many of the ship’s company considered the sojourn into northern waters “a welcome relief from Kamikaze attacks, swimmers burdened with underwater bombs, not to mention the hot tropic climate.” As Fanshaw Bay threaded through the coral reef at Eniwetok out to sea, she heard the electrifying announcement of the Japanese agreement to surrender.

The ship continued the voyage and put in to Kulak Bay on the Bering (northwestern) side of Adak Island in the Aleutians. The carrier anchored amidst her companions in the shadow of show-capped peaks surmounting the treeless green tundra. From there, Fanshaw Bay sailed in TF 44 and participated in the occupation of the northern Japanese home islands (31 August–9 September 1945). Fanshaw Bay took the van station of the escort carriers as she led them through the narrow Tsugaru Strait on the 7th, and then helped cover troops when they landed and occupied Ōminato in northern Hokkaido. The Japanese had used the port as their main naval station in the north, and although rumors circulated that the enemy might oppose the landings, the garrison obeyed their high command’s orders to surrender without resisting, and signed the terms on the 9th. The ship returned to Pearl Harbor on 24 September 1945, where Rear Adm. Ernest W. Litch, who had relieved Sprague during the fighting for Okinawa on 7 April, lowered his flag and went ashore.

Fanshaw Bay’s chronicler recorded that she spent 124 days in action; claimed the destruction of 16 Japanese planes in the air and 42 on the ground; took part in attacks that sank five ships of over 1,000 tons and 51 vessels of under 1,000; damaged 23 ships of more than 1,000 tons and 66 under 1,000; struck 229 shore targets. In addition, she steamed more than 150,000 miles; crossed the equator ten times; and the International Date Line on 14 occasions.

Following the Japanese surrender, debates concerning the point system for discharges punctuated the conversations of the ship’s company, but they then took part in Operation Magic Carpet—the return of veterans from the war zones by ships and aircraft. Fanshaw Bay turned to the new task with her characteristic vigor and in the following months steamed more than 23,500 miles with an average of 1,400 passengers embarked for each voyage.

The carrier accomplished her mission in spite of a cut in her own complement because of discharges, as well as frequent mechanical failures. Fanshaw Bay lay to at San Francisco (20–21 October 1945), Pearl Harbor on the 27th, and the following day at Kahului, Maui, T.H., and returned veterans of the Fourth Marine Division, including men of the 14th Marines, 4th Marine Engineer Battalion, 4th Marine Motor Transport Battalion, and the 4th Marine Assault Signal Company, to the west coast, where they disembarked at San Diego (4–7 November).

The ship made a final voyage to Japanese waters, stopping at Pearl Harbor (14–19 November) en route and reaching Tōkyō Bay (28 November–5 December), to return men of all the services to San Diego. Three of her four boilers broke down during the return trip from Yokosuka (5–18 December), but she safely brought the men home.

Fanshaw Bay steamed northward to San Pedro, Calif., on 19 December 1945, Port Angeles on 26 January 1946, and her final underway watch ended at 1155 on 29 January, when she moored at Tacoma, Wash., and began the lengthy overhaul and inactivation process. The ship was placed out of commission in reserve at Tacoma on 14 August 1946, a status in which she remained. Fanshaw Bay was reclassified to an escort helicopter aircraft carrier (CVHE-70) on 12 June 1955 while she lay inactive.

Stricken from the list of U.S. United States Navy Ships on 1 March 1959, ex-Fanshaw Bay was sold on 29 August 1959 to Hyman-Michaels Co., Chicago, Ill., and was scrapped in Portland, Ore., later that same year.

Fanshaw Bay shared in the award of the Presidential Unit Citation to Taffy 3 for extraordinary heroism in the Battle off Samar and received five battle stars for her World War II service.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Capt. Douglass P. Johnson | 9 December 1943 |

| Capt. Murr E. Arnold | 10 January 1945 |

| Capt. Marshall B. Gurney | 9 September 1945 |

| Cmdr. Harold S. Bottomley Jr. | 29 January 1946 |

Mark L. Evans

22 October 2019