Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Happy 248th Birthday, U.S. Navy!

On Oct. 13, 1775, a resolution by the Continental Congress established the foundation for what is now the United States Navy: “a swift sailing vessel, to carry ten carriage guns, and a proportional number of swivels, with eighty men, be fitted, with all possible dispatch, for a cruise of three months.” Following the American Revolution and after much debate, the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1788, empowered Congress “to provide and maintain a navy.” Acting on this authority, the Department of the Navy was established on April 30, 1798. In 1972, Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Elmo R. Zumwalt, Jr., officially authorized Oct. 13 as the Navy’s birthday. This year’s theme is “248 Years of Power, Presence, and Protection,” which highlights the U.S. Navy’s historical and long-standing commitment to being forward deployed, highly trained, and dedicated to defending American interests at sea, on land, and in the sky.

After the colonies had gained their independence from Great Britain in 1783, the Continental Navy was deemed irrelevant and thought to be too expensive to continue and fund. The 13 former colonies had a loose arrangement of sovereignty, and the federal government did not have the taxation powers to fund the construction of new ships and training sailors. In addition, the newly established peace with England also appeared to make a new American navy unnecessary. Nevertheless, danger remained present on the high seas. In 1785, Barbary pirates seized their first of many American vessels and tried to ransom the passengers and crew. American merchant ships were considered helpless against foreign attacks. In addition, increasingly volatile relations among the United States, Great Britain, and France further complicated the issue of security for free trade among sovereign nations. Over the course of the French Revolutionary Wars, which quickly spilled out into the Atlantic, American neutrality became tenuous. American merchants pressed Congress for a standing naval force that could defend them against ships of war and pirates. Furthermore, when France and Britain began to wage economic war on each other, the British government blocked American ships from the West Indies—a crucial source for sugar and other commodities. To complicate matters further, British ships harassed and attacked American merchants in an effort to choke the economy of France and diminish French war-making capabilities. President George Washington and Secretary of State Edmund Randolph implored Congress to take action for the sake of America’s neutrality status.

Nonetheless, Congress continued to ignore the requests. As the President, his supporters, and many in the Federalist Party saw a navy securing prosperity at home and guaranteeing protection on the high seas, Anti-Federalists had their reservations. Those not in favor of a navy did not want to add to the young country’s debt and believed that the British would be further infuriated. Ultimately, the situation in the Mediterranean began to force the issue. In early 1794, Barbary pirates, having signed a truce with Portugal and been paid off by the British, began to attack any American ship. Finally, on Jan. 2, 1794, Congress decided to create “a naval force, adequate to the protection of the United States against the Algerine corsairs.” A committee was formed, and it recommended a fleet of six frigates be constructed or purchased. Congress approved the recommendations, and on March 27, 1794, President Washington signed “An act to provide a naval armament,” which established the U.S. Navy.

In order to distribute the government’s appropriation fairly and speed up production, the six original frigates were built simultaneously in six different locations along the U.S. Atlantic coast. The following port towns were chosen as the building sites for the frigates: Philadelphia for United States; Baltimore for Constellation; Boston for Constitution; New Hampshire for Congress; New York for President; and Gosport (Norfolk, Virginia) for Chesapeake. By 1797, United States, Constellation, and Constitution had been launched and were ready for sea duty. Congress, Chesapeake, and President were launched over the following two years.

On Oct. 2, 1799, the Washington Navy Yard was established under the direction of Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert and the supervision of Commodore Thomas Tingey, who served as commandant of the District of Columbia navy yard for the next 29 years. As the nation’s first navy yard and homeport, shipbuilding and ship fitting were the dominant activities in the early years. Twenty-two vessels were ultimately constructed at the Washington Navy Yard, ranging from 70-foot gunboats to the 246-foot steam frigate Minnesota, completed in 1855. During the War of 1812, the Washington Navy Yard remained an important support facility and a strategic location in the defense of the nation’s capital city. As the British occupied Washington in 1814, Tingey ordered the yard burned so that the enemy could not utilize the strategic location. Over the years, the Washington Navy Yard has carried out multiple functions ranging from the development and fabrication of ordnance and technology to the production of 14-inch naval railway gun barrels during World War I. The Washington Navy Yard is still in operation today but consists mostly of administrative space.

On the issue of national security, the U.S. Navy continues to be the world’s leading maritime deterrent. During the War of 1812, Constitution’s victory over HMS Guerriere on Aug. 19, 1812, inspired a young nation to challenge the vastly superior Royal Navy. (Constitution—homeported at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston—is the world’s oldest commissioned warship afloat and the world’s oldest sailing vessel still capable of sailing under its own power). During the Civil War, the Navy’s role in amphibious, riverine, and blockading operations contributed greatly in defeating the Confederacy and preserving the nation’s unity. The Navy’s convoy escorts and submarine chasers ensured Allied victory in World War I. During World War II, the American Navy defeated the Japanese Imperial Navy in some of the most decisive victories in naval history. In the Pacific theater, the Battle of Midway changed the course of the war and victories at Saipan, in the Philippine Sea, and at Leyte Gulf, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa led to Japan’s surrender. In the Atlantic, the Navy helped defeat the German U-boat threat. In an as-yet-unparalleled operation, nearly 7,000 U.S. Navy and British vessels landed upward of 160,000 troops on the beaches of Normandy. The sacrifice and unrivaled success of the U.S. submarine force was a significant factor in the defeat of Imperial Japan. During the Korean War, the service supported the Inchon landings, the Chosin Reservoir operation, and the naval blockade of North Korea. In Vietnam, the Navy flew around-the-clock air strikes and close-support missions, blockaded North Vietnamese waters, successfully interdicted North Vietnamese maritime supply, and provided crucial gunfire support. The Navy’s “brown water” riverine forces also made significant contributions during operations on the waterways of Vietnam. In recent years, U.S. Navy ships were among the first to fire Tomahawk missiles into Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria.

Finally, people have always been the most important part of the Navy. From the likes of John Paul Jones and Oliver Hazard Perry to Chester Nimitz and Jesse L. Brown, the Navy’s rich history reflects its people and their commitment to serve this great country. Today’s Sailors are no different. They are 100 percent on watch 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and have been for 248 years. Happy Birthday, U.S. Navy! For resources for your Navy birthday celebration, check out NHHC’s Navy birthday toolkit on NHHC’s website.

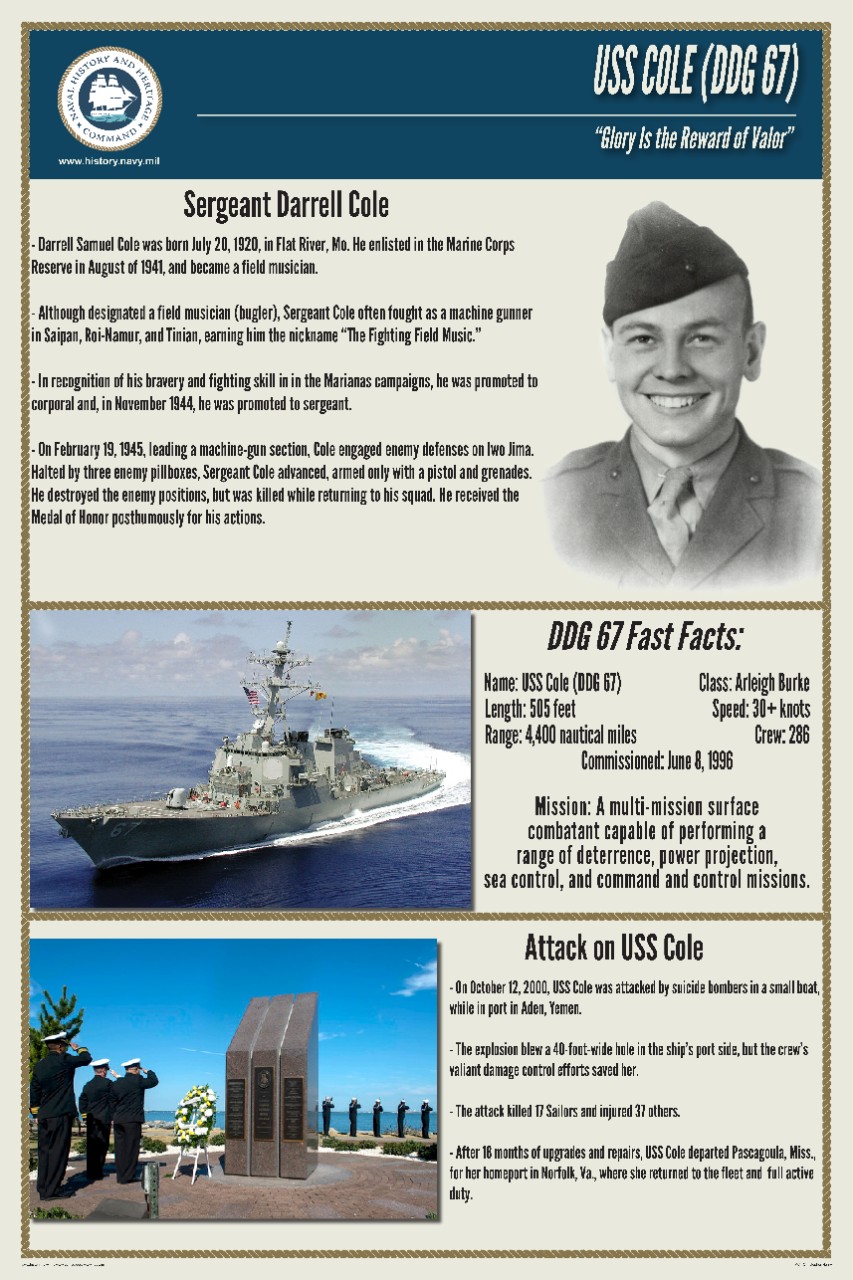

USS Cole Attacked

On the morning of Oct. 12, 2000, USS Cole (DDG-67) was deployed in company with guided-missile frigate USS Sampson (FFG-56) and Military Sealift Command–manned oiler USNS John Lenthall (T-AO-189) to the Mediterranean, Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Indian Ocean. While refueling at Aden, Yemen, two al-Qaeda terrorists detonated an explosive-laden speedboat directly against the port side of Cole. The blast tore a 40-by-60-foot hole in the ship’s hull that killed 17 American Sailors and wounded another 37. In the aftermath of the suicide attack, the crew fought tirelessly for more than 96 hours to free shipmates trapped by the twisted wreckage and limit flooding that threatened to sink the ship. The crew’s prompt actions to isolate damaged electrical systems and contain fuel oil ruptures prevented catastrophic fires that could have engulfed the ship and cost the lives of countless others. Deprived of sleep, food, and shelter, the crew vigilantly battled to preserve a secure perimeter and restore stability to engineering systems that were vital to the ship’s survival. In addition, first aid and advanced medical treatment prevented additional deaths and eased the suffering of others.

In wake of the attack, Operation Determined Response was initiated to recover the crippled ship and secure the area. After completing emergent repairs, heavy lift vessel Blue Marlin loaded the destroyer on board at Aden and carried it to Pascagoula, Mississippi, for extensive repairs, reaching that port on Dec. 13. Cole’s crewmembers, meanwhile, embarked on board USS Tarawa (LHA-1) on Dec. 1. They were then taken to aircraft that flew them to Rhine-Main Air Force Base, Germany, the next day, and from there back to Norfolk, Virginia. The ship returned to the water on Christmas Eve, though repairs and maintenance continued into 2001. It is still active today. The ship’s captain, Cmdr. Kirk S. Lippold, received the Legion of Merit for his “exceptionally meritorious conduct.” Four Sailors received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal and 54 received the Purple Heart. The ship received a Navy Unit Commendation.

One year after the terrorist attack, a memorial was dedicated in Norfolk to remember and honor the 17 Sailors that were killed. The memorial consists of three sections. The main plaza of the memorial contains three 10-foot monoliths that represent the three colors of the American flag. Encircling the monoliths are 17 low-level markers that represent the victims of the bombing. Three plaques are present at the monument. The two outside pillars contain the names of the Sailors killed during the bombing, and the center pillar exhibits the USS Cole emblem and an inscription that reads, “In lasting tribute to their Honor, Courage and Commitment.” Along the path to the memorial are 28 pine trees that represent the 17 victims and the 11 children who lost their parents during the bombing. Also along the path is a plaque that marks the location of the USS Cole Memorial Tree that was planted by the Hampton Roads Council of the Navy League during the dedication ceremony. The tree’s plaque reads, “You will forever be in our thoughts, our memories never forgotten, you will live in our hearts, and may this tree remind every ship rolling by, of your sacrifice.” At the end of the path is a raised plaque that details the events of the bombing and amplifies the heroic efforts to save ship and their shipmates. Part of the inscription reads, “As a permanent symbol of that strength and resolve, steel from the ship’s damaged hull is forged into this plaque. The crew of the USS Cole personified honor, courage, and commitment.” Naval History and Heritage Command has four artifacts in its holding from Cole— a Navy flag, a Marine Corps flag, a mess management specialist t-shirt, and a mess deck tray. For more on the Cole attack, read H-Gram 055 by NHHC Director Sam Cox.

Operation Enduring Freedom

In response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks that killed nearly 3,000 people from 93 different countries, Operation Enduring Freedom officially began on Oct. 7, 2001, with the commencement of military operations in Afghanistan. F-14 Tomcats and F/A-18 Hornets—launched from USS Enterprise (CVN-65) and USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70)—struck preplanned targets in and around Kabul, Herat, Shindand, Shibarghan, Mazar-i-Sharif, and the southern Taliban stronghold of Kandahar with laser-guided bombs, Joint Direct Attack Munitions, the AGM-84 Standoff Land Attack Missiles–Extended Range, and the AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon. Strike aircraft were supported by accompanying F-14 and F/A-18 fighter sweeps and by electronic jamming of Taliban radar and communications transmissions by EA-6B Prowlers. Strike missions from Enterprise and Carl Vinson covered distances to targets of 600 nautical miles or more, with an average sortie length of more than four and a half hours and a minimum of two inflight refuelings each way. USS McFaul (DDG-74), USS John Paul Jones (DDG-53), USS O’Brien (DD-975), USS Philippine Sea (CG-58), and USS Providence (SSN-719), as well as two British submarines, HMS Triumph and HMS Trafalgar, fired 50 Tomahawk missiles against fixed, high-priority targets in Afghanistan. President George W. Bush addressed the nation in a televised address: “On my orders, the United States military has begun strikes against al-Qaeda terrorist training camps and military installations of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. These carefully targeted actions are designed to disrupt the use of Afghanistan as a terrorist base of operations and to attack the military capability of the Taliban regime.”

Initially, the Taliban was removed from power and al-Qaeda was seriously crippled, but allied forces continually dealt with a stubborn Taliban insurgency, infrastructure rebuilding, and endemic corruption in the Afghan National Army, Afghan National Police, and Afghan Border Police—and in the Afghan government itself. On May 2, 2011, U.S. Navy SEALs launched a raid on Osama Bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, killing the al-Qaeda leader and mastermind of the Sept. 11 attacks. Operation Enduring Freedom officially ended on Dec. 28, 2014, although coalition forces remained on the ground to assist with training Afghan security forces. The United States Armed Forces completed its withdrawal from Afghanistan on Aug. 30, 2021, marking the end of the 20-year war.

There were three U.S. Navy Medal of Honor recipients during Operation Enduring Freedom: Lt. (SEAL) Michael P. Murphy, Senior Chief Special Warfare Operator (SEAL) Edward C. Byers, Jr., and Master Chief Petty Officer (SEAL) Britt Slabinski.

Today in Naval History—Mercury-Atlas 8 Mission

On Oct. 3, 1962, Sigma 7 (Mercury-Atlas 8) was launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida. The spacecraft was piloted by Navy Cmdr. Walter M. Schirra, Jr. and lasted 9 hours and 13 minutes. Schirra made six orbits at an altitude up to 175.8 statute miles at 17,558 miles per hour. It was the longest mission NASA had attempted at the time. The mission provided NASA with validation of the spacecraft’s performance over longer flights, while also providing data on longer exposure in space and the effects on the human body. Schirra, who advocated early in the design process for a spacecraft that could be controlled manually as well as automatically, spent more than two hours of the flight drifting in orbit on manual control. When the mission was complete, space capsule Sigma 7 splashed down in the central Pacific Ocean just half a mile from aircraft carrier USS Kearsarge (CVS-33), which carried out Schirra and Sigma 7’s retrieval.

Schirra went on to command Gemini 6A, the first mission to include a rendezvous in space—a maneuver that would be crucial to the success of the Apollo program. Later, Schirra was commander of the highly successful Apollo 7 mission, after which he retired from NASA and the U.S. Navy. Before becoming an astronaut, Schirra was a naval aviator. During the Korean War, he flew 90 combat missions. After the war, he was a test pilot working on the development of the Sidewinder missile at the Naval Ordnance Test Station at China Lake, California. When he was accepted into NASA, Schirra was one of the original seven Mercury astronauts, which also included L. Gordon Cooper, Jr.; Alan B. Shepard, Jr.; Virgil I. Grissom; John H. Glenn, Jr.; Donald K. Slayton; and M. Scott Carpenter

After he retired, Schirra continued his connection with the American space program by covering the subsequent Apollo flights for the CBS network alongside Walter Cronkite. Throughout his career as both an astronaut and naval officer, Schirra logged a total of 3,200 hours in flying. He went on to receive three honorary doctorate degrees in his lifetime, as well as attain more than 10 highly prestigious awards and honors. Schirra was inducted into the International Aviation Hall of Fame in 1970, New Jersey Aviation Hall of Fame in 1977, International Space Hall of Fame in 1981, and the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1986. Schirra passed away on May 2, 2007, at the age of 84. On Feb. 11, 2008, his ashes and those of eight other Navy veterans were committed to the sea during a special burial at sea ceremony on board USS Ronald Reagan (CVN-76). For more on the Navy’s role in space exploration, visit NHHC’s website.