Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

"Date That Will Live In Infamy"

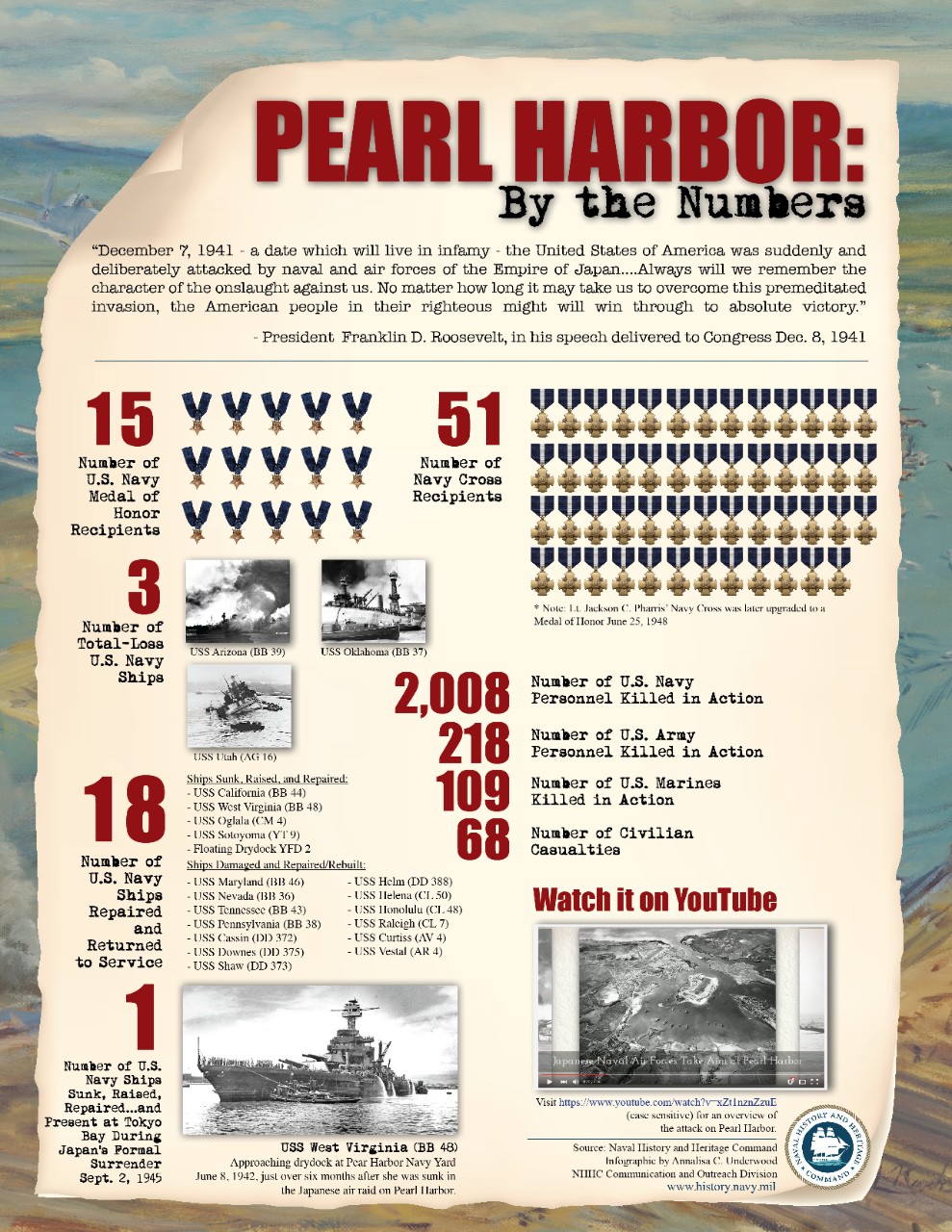

On a quiet Sunday morning on Dec. 7, 1941, in one of the most significant moments in U.S. history, two waves of Japanese Imperial Navy aircraft attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet and nearby military airfields and installations at Pearl Harbor. The first wave—more than 170 dive-bombers, torpedo planes, and fighters—appeared over Pearl Harbor at 7:55 a.m. Within the first 30 minutes, most of the damage had been done. At the airfields on Ford Island and adjoining Wheeler and Hickam Fields, American aircraft were parked closely together, which made them easy targets for Japanese strafing. At Wheeler Field, in particular, of the 126 planes on the ground, 42 were destroyed and 41 were damaged, leaving only 43 fit for service. Only a handful of U.S. aircraft were able to get into the air to repel the first wave of attacks. In all, more than 180 U.S. aircraft were destroyed. As for the ships anchored at Pearl Harbor, Battleship Row was in complete shambles. USS Arizona (BB-39) took two bomb hits, which triggered a catastrophic explosion that ripped through the forward part of ship. USS West Virginia (BB-48) was riddled with bombs and torpedoes, but was not sunk due to extraordinary damage control measures. USS Oklahoma (BB-37) sustained three torpedo hits almost immediately. As it capsized, six more torpedoes struck the ship. USS California (BB-44) was torpedoed and ordered abandoned as it slowly sank in shallow water. USS Utah (AG-16) took a torpedo hit and rolled over.

At 8:50 a.m., the second wave of the attack—with more than 160 enemy aircraft–began. Although less successful than the first, it nonetheless inflicted heavy damage. USS Nevada (BB-36), which had taken a torpedo hit during the first wave of the attack, was struck by seven or eight bombs and was grounded at the head of the Pearl Harbor channel. Dry-docked USS Pennsylvania (BB-38) was set ablaze by bombs, and the two destroyers in dry dock with it were reduced to wrecks. Destroyer USS Shaw (DD-373) took three bomb hits that sparked widespread fires, causing its forward magazine to blow up. Shortly afterward, the Japanese withdrew.

Casualties were staggering—2,008 Navy, 109 Marine Corps, 218 Army, and 68 civilian personnel were killed or missing. More than 1,100 were wounded. Arizona suffered the most casualties, with 1,177 of the 1,512 on board the ship losing their lives. More than 400 were lost on board Oklahoma. Japanese losses amounted to fewer than 100 men, 29 planes, and 5 midget submarines.

Although the attacks were devastating to the Pacific Fleet, none of the American aircraft carriers were at Pearl Harbor at the time. USS Enterprise (CV-6) was on a mission to reinforce the Wake Island garrison, USS Lexington (CV-2) was undertaking a similar mission to ferry dive-bombers to Midway, and USS Saratoga (CV-3) was embarking aircraft in San Diego. These operations also meant that seven heavy cruisers and a division of destroyers were at sea. In addition, the Japanese focus on ships and planes spared fuel tank farms, naval yard repair facilities, and the submarine base, which would be crucial in the upcoming months. Moreover, only three ships, Arizona, Oklahoma, and Utah, were ultimately lost. The rest of the ships damaged during the Pearl Harbor attack were repaired or rebuilt and returned to the fleet. In the aftermath, President Franklin D. Roosevelt unified the American public and dispelled any earlier support for U.S. neutrality. On Dec. 8, Congress declared war on Japan. On Dec. 11, Japan’s allies, Germany and Italy, declared war on the United States. Although the war had begun in 1939 and the United States did not want to be involved in another global conflict, World War II had finally arrived on the shores of the country.

Acts of extraordinary bravery were in abundance on the “date that will live in infamy.” Often at the sacrifice of their own lives, Sailors, Marines, and Soldiers fought back. Those without weapons helped in any way they could. Nurses, doctors, and corpsmen spent countless hours evacuating and tending to the wounded. Pilots took off in their aircraft to fight the Japanese despite overwhelming odds. Fifteen Navy personnel would later receive the Medal of Honor (10 posthumously) for acts of courage above and beyond the call of duty. Among the Sailors recognized with the nation’s highest honor who made the ultimate sacrifice were Chief Water Tender Peter Tomich onboard Utah, who gave his life to prevent the boilers from exploding, enabling boiler room crews to escape before the ship capsized. Another was Chief Boatswain’s Mate Edwin J. Hill, who cast off the lines as Nevada got underway and then swam through burning oil to get back on board his ship, where he was killed by Japanese strafing. He was credited with saving the lives of many junior Sailors. Ensign Francis Flaherty and Seaman First Class James Richard Ward, on board Oklahoma, sacrificed their lives to enable turret crews to escape before the ship capsized. On board California, Chief Radioman Thomas J. Reeves, Machinist's Mate First Class Robert R. Scott, and Ensign Herbert C. Jones stayed at their posts at the cost of their lives to keep power and ammunition flowing to the antiaircraft guns as long as possible. Rear Adm. Isaac C. Kidd and Capt. Franklin Van Valkenburgh on board Arizona and Capt. Mervyn S. Bennion on board West Virginia directed the defense of their ships under heavy fire, until the ships were sunk and they were killed. Fifty-one Navy personnel were also awarded the Navy Cross.

When the American public initially learned of the attack, they reacted with predictable shock and disbelief. The devastation in Hawaii had a widespread impact on life in the United States, both physically and psychologically. Homes and businesses hung blackout curtains in their windows, citizens were issued gas masks, and businesses that were able to continue to operate did so at all times of day and night to ease transport issues. Supplies were limited, but everyone worked together to start the cleanup. Young men started to enlist, and the number of Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines quickly grew to more than 135,000 (twice that of the three services before the attack). In Hawaii and on the U.S. East and West Coasts, more gun batteries were emplaced, beaches were surrounded with barbed wire, and many major buildings were painted in camouflage. At night, citizens turned off all their lights (or had limited lighting) and all major provisions, such as fuel, were rationed.

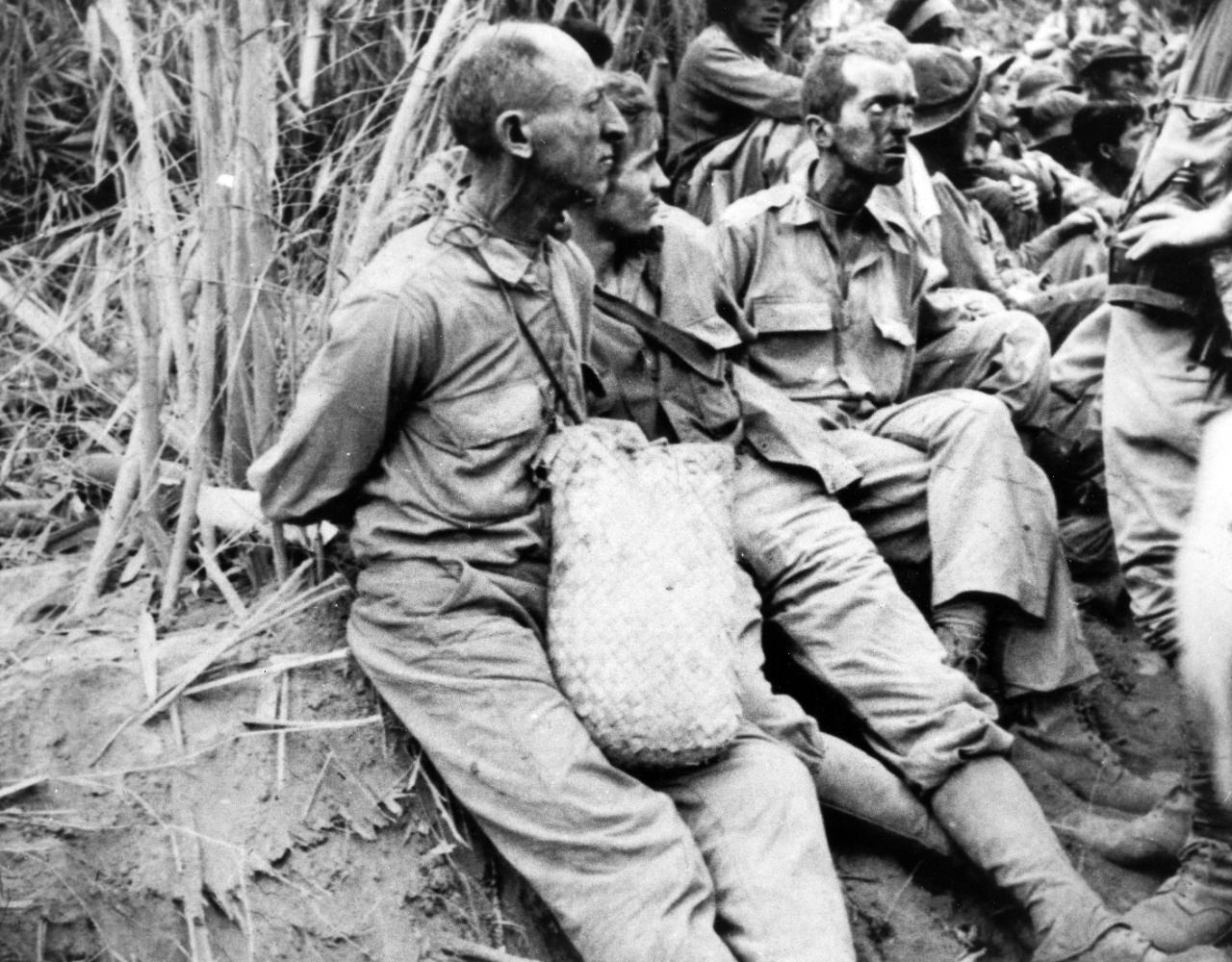

The attack on Pearl Harbor, led by Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, was a huge gamble for Japan and the Imperial Japanese Navy. Japan deployed all six of its fleet carriers across 3,000 miles of open ocean in total secrecy, arriving a few hundred miles north of the Hawaiian Islands, where they launched their attacks. After the attacks, while the U.S. Pacific Fleet was temporarily crippled, a massive Japanese offensive overran European colonial possessions in Asia, including Hong Kong, Malaya, and the Dutch East Indies. U.S. territories also came under attack—the Philippines, Guam, and Wake Island. The Japanese assault seemed unstoppable and led to two mass surrenders. At Singapore, 80,000 British, Indian, and Australian troops went into captivity in February 1942. In the Philippines, Japanese forces outmaneuvered the combined U.S./Philippine force under Gen. Douglas MacArthur, which led to the surrender of 75,000 troops in April 1942. It was the worst military defeat in U.S. history. The prisoners of war were forced to march a brutal 65-mile trek from the Bataan Peninsula to camps at Cabanatuan in central Luzon (known as the Bataan Death March). Over the course of the five-day march, at least 5,000 died, a grim sign of what was to come in what the Japanese called the Great Pacific War.

America’s Game: The Rivalry Continues

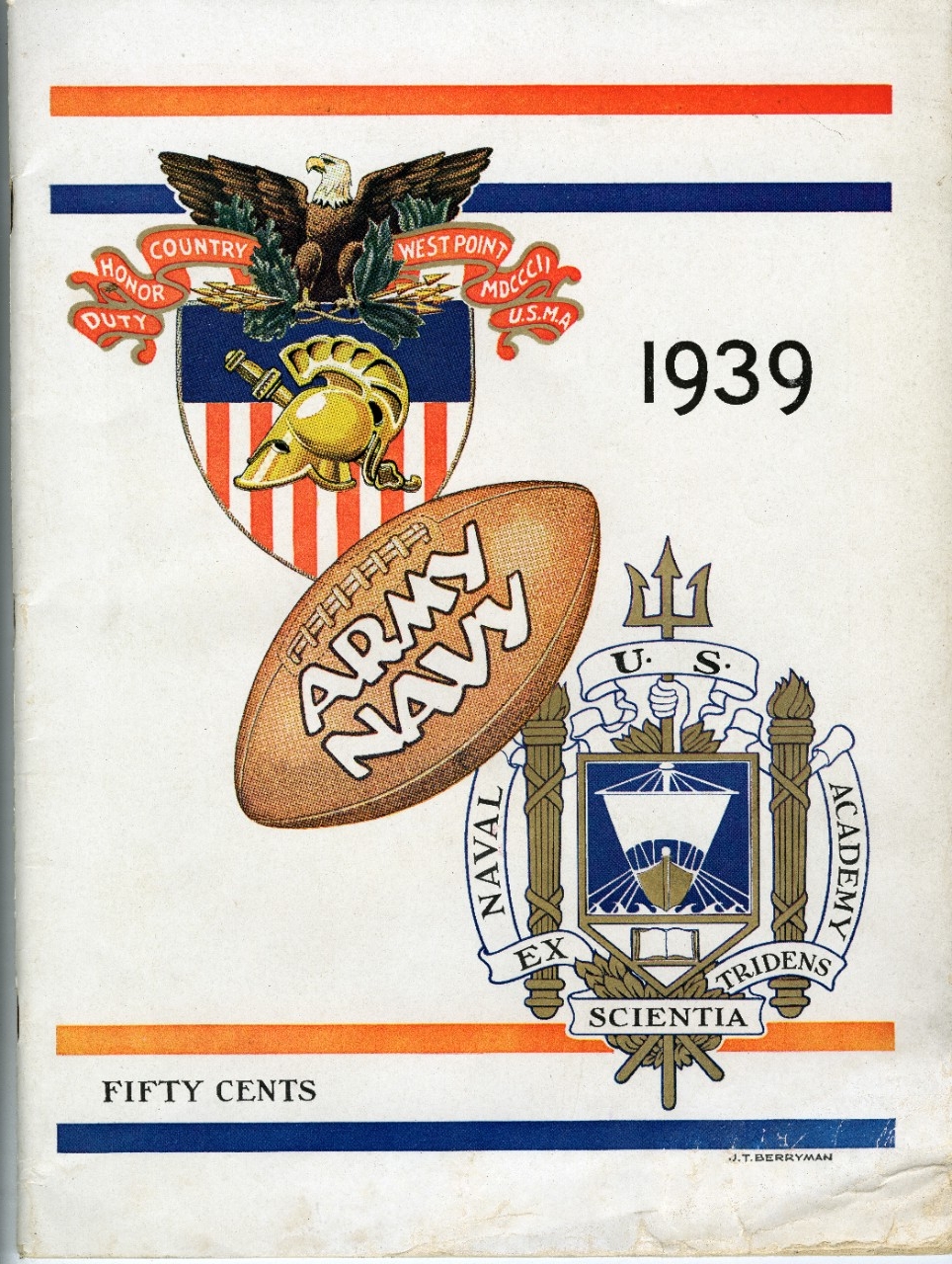

Go Navy! Beat Army! It is one of the most traditional and enduring rivalries in college football. Dubbed “America’s Game,” the 124th Army-Navy football game is scheduled to take place this year on Dec. 9 at 3 p.m. at Gillette Stadium in Foxborough, Massachusetts. It will be the first time the game will be played in the greater Boston area, and only the third time it has been played outside the mid-Atlantic region (the other two were in Chicago in 1916 and Pasadena, California, in 1983). The Navy Midshipmen currently lead the overall series 62–54–7.

In what has become a tradition, both teams will wear alternate uniforms for the big game. This year, Navy will wear uniforms honoring the submarine force. Every element of the Midshipmen uniform, from the helmets down to the gloves, references the “Silent Service” in some form or fashion. For example, the helmets are painted with a Virginia-class submarine on one side, with the other featuring the Navy’s fouled anchor emblem integrated with a submarine warfare pin. As for Army, they will continue the team’s tradition of honoring specific units. This year, the Black Knights are paying homage to the 3rd Infantry Division. The 3rd Infantry Division was activated on Nov. 21, 1917, the same year the United States entered World War I, but Army has chosen a more modern take. The Black Knights will be wearing tan to denote the desert in which the 3rd Infantry Division operated during Operation Iraqi Freedom. The 3rd Infantry Division served as the tip of the spear during the land invasion of Iraq in 2003. Army’s uniform is replete with small details honoring the division. The Black Knights will wear helmets emblazoned with “Rocky the Bulldog,” the division’s official mascot. Each player will wear the number and corresponding callsign of one of the division’s three brigades on the back of his helmet. The uniform also exhibits common divisional armored vehicle markings.

The rivalry game between Army and Navy was first played at West Point, New York, on Nov. 29, 1890. Navy won the contest 24–0. The midshipmen had an advantage for their first game against the cadets because they had been playing football since 1879. Army had just started playing in 1890. In the early years, the game was cancelled a number of times. From 1894 to 1898, it was mandated that the service schools could only play home games, and due to World War I, the game was cancelled in 1917 and 1918. Disagreement about the rules also cancelled the game in 1928 and 1929. The game became an annual event in 1930 and was even played throughout World War II. Recently, victories have been back and forth. Last year, Army won 20–17 in the first overtime game in the rivalry series. From 2002 to 2015, Navy dominated Army with 14 straight wins. Army’s longest winning streak was five games from 1992 to 1996.

Traditions have also become an integral part of the game. Mascots will be present throughout the game. The Navy’s mascot is a goat (Billy) and the Army’s is a mule (Ranger). “March On” opens the game, when both midshipmen and cadets assemble on the field in formation. Another tradition before the game is the “prisoner exchange.” As part of the Service Academy Exchange Program, some midshipmen and cadets spend the fall semester at the other service’s academy. Midshipmen and cadets who participate are sent back to their home team to root for their school. If the President of the United States is in attendance, he changes sides during halftime to show support for both Army and Navy. Once the game is complete, the singing of the alma maters takes place. The team that lost sings first, followed by the players and alumni of the winning team. For more on Navy athletics and scores from all the Army-Navy football games, visit NHHC’s website.

Jacob Jones Sunk, German Commander’s Act of Chivalry

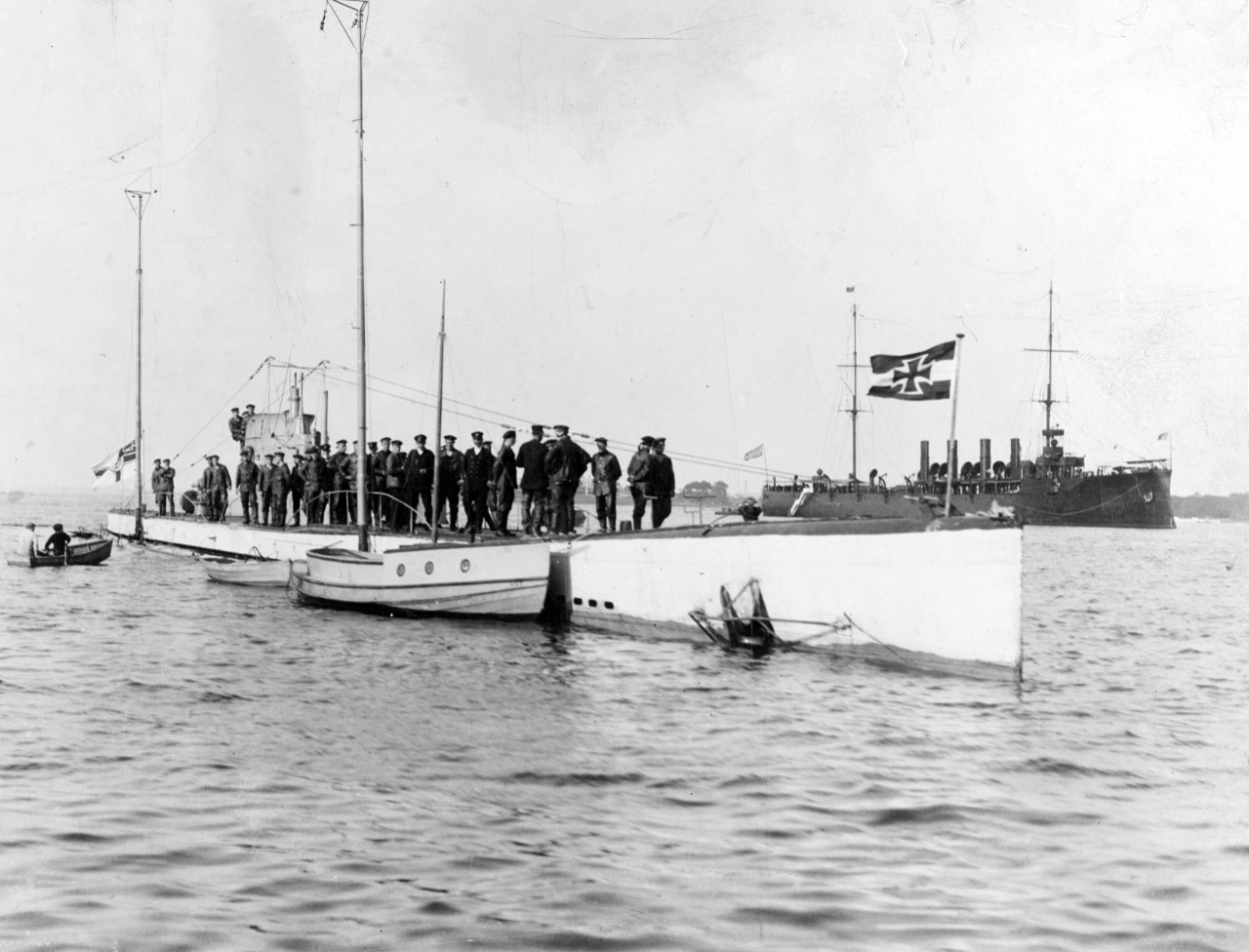

On Dec. 6, 1917, during World War I, USS Jacob Jones (DD-61) had just finished escorting a convoy off Brest, France, and set course for Queenstown, Ireland, holding target practice that afternoon. The gunfire from the exercise attracted the attention of German submarine U-53, which was in the vicinity. Under the command of Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, the U-boat stalked the American destroyer undetected and fired a torpedo from its bow tubes. At 4:21 p.m., the cry of “Torpedo!” pierced the cold air and drew attention to a perfectly straight wake speeding toward the ship off of the starboard beam. The officer of the deck ordered the rudder put hard left, while the ship’s commanding officer, Lt. Cmdr. David W. Bagley, rang up emergency speed as the ship began to turn. The torpedo closed, broaching then plunging beneath the waves approximately 60 feet away from the starboard side. It struck Jacob Jones three feet below the waterline in the fuel oil tank between the auxiliary room and the after crew space. Upon impact, many members of the crew were killed instantly. Compartments immediately took on water from the frigid winter sea. The crew struggled to seal the watertight door between the auxiliary compartment and the engine room against the intense pressure of the encroaching water, but the task proved fruitless. In desperation, Bagley attempted to send an SOS to friendly forces, but the ship’s antenna had been carried away by the explosion and the sea.

Topside, the crew raced against the rising water to cut loose lifebelts, boats, life rafts, and pretty much anything that could float. The gunnery officer attempted to reach the depth charges to set them on safe, but he could not get to them due to the damaged and twisted stern. Meanwhile, Bagley ran along the deck and ordered the crew to abandon ship. The executive officer gave orders to shut off the steam. In a final attempt to draw the attention of any friendly vessels in the area, the No. 4 gun was fired twice. At 4:29 p.m., only eight minutes after being torpedoed, the bow of the destroyer swung upward, twisting 180 degrees in the process, and pausing nearly upright before Jacob Jones plunged into the icy waters stern first.

The survivors’ ordeal continued after escaping the ship. As the ship sank, numerous depth charges exploded, killing several of the crew in the water. In the process of abandoning the ship, many Sailors had been only lightly clad, and they struggled in the frigid ocean. Survivors pulled their shipmates on board the remaining lifeboats, the one motor dory, a few rafts, and a leaky wherry. Others literally took the shirts off their own backs in attempts to keep their shipmates warm and alive. As the survivors endured, U-53 surfaced and subsequently brought two seriously injured American Sailors on board before it submerged. One of the crewmembers, taken below to the cramped confines of the German boat, noticed the wireless operator transmitting a message, turned to Rose, and asked, “Notifying your sister ship of your victory?” Rose responded, “No, I am sending an SOS to Land’s End [England] for the remainder of your shipmates as I have no more room for more of you aboard.” It was a rare gesture of goodwill during the “Great War” and was praised in post-war accounts as an act of chivalry uncommon in modern warfare.

Three and a half hours after the sinking, British steamer Catalina recovered seven of Jacob Jones’ survivors and radioed for additional help. The British sloop HMS Camellia recovered the main group of survivors in three boats at 8:30 a.m. the following day. Earlier, Bagley had led the surviving motor dory toward the Scilly Islands to seek help, and a British patrol boat picked that group up at 1 p.m. The leaky wherry containing five crewmembers also set out for the Scilly Islands but was never seen again and likely sank. Of the 110 crewmembers on board the vessel, 62 died in the attack and its aftermath.

For their actions during the loss of Jacob Jones, the Navy awarded Bagley and Lt. (j.g.) Stanton F. Kalk, the officer of the deck, the Distinguished Service Medal (at that time a higher award than the Navy Cross). Kalk’s was awarded posthumously. Four other members of the crew were awarded the Navy Cross. The Navy later named three destroyers in honor of Bagley and Kalk—USS Bagley (DD-1069), USS Kalk (Destroyer No. 170), and USS Kalk (DD-611). DD-1069 was named for both David Bagley and with his brother Worth, who was the only naval officer killed in action during the Spanish-American War. For more on the ordeal of Jacob Jones, read H-Gram 013-5 by NHHC Director Sam Cox on NHHC’s website.

Of note, after Jacob Jones was lost and stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on Dec. 17, 1917, the ship’s name was quickly given to a new-construction destroyer USS Jacob Jones (DD-130), which was commissioned in 1919. It was also sunk by a German submarine—U-578—on Feb. 28, 1942, during World War II. Only 12 crewmembers survived the sinking. The following year, another Jacob Jones, DE-130, was commissioned. It survived the war and was not stricken from the Naval Vessel Register until 1971.

Today in Naval History—Birth of the Navy’s Chaplain Corps

On Nov. 28, 1775, the U.S. Navy’s Chaplain Corps was established after Congress adopted the first Rules for Regulation of the Navy of the United Colonies of North America. Article II of the regulations stated, “The commanders of the ships of the Thirteen United Colonies are to take care that divine service be performed twice a day on board, and a sermon preached on Sundays, unless bad weather or other extraordinary accidents prevent it.”

The first Navy chaplain is believed to have been Reverend Benjamin Balch. Balch was a Congregational minister who was educated at Harvard. His father served as a chaplain in King George’s War in 1745. Prior to becoming a Navy chaplain, the younger Balch fought at Lexington as a minuteman and served as an Army chaplain during the siege of Boston. On Oct. 28, 1778, Balch reported aboard the frigate Boston and served aboard it until the ship was captured by the British during the siege of Charleston, South Carolina, in May 1780. He then served aboard the frigate Alliance under the command of Commodore John Barry. Due to Balch’s combat service, which included Alliance’s sea battles, he earned the nickname “Fightin’ Parson.” After the American Revolution was won and the Colonies gained their independence, the Continental Navy was dissolved.

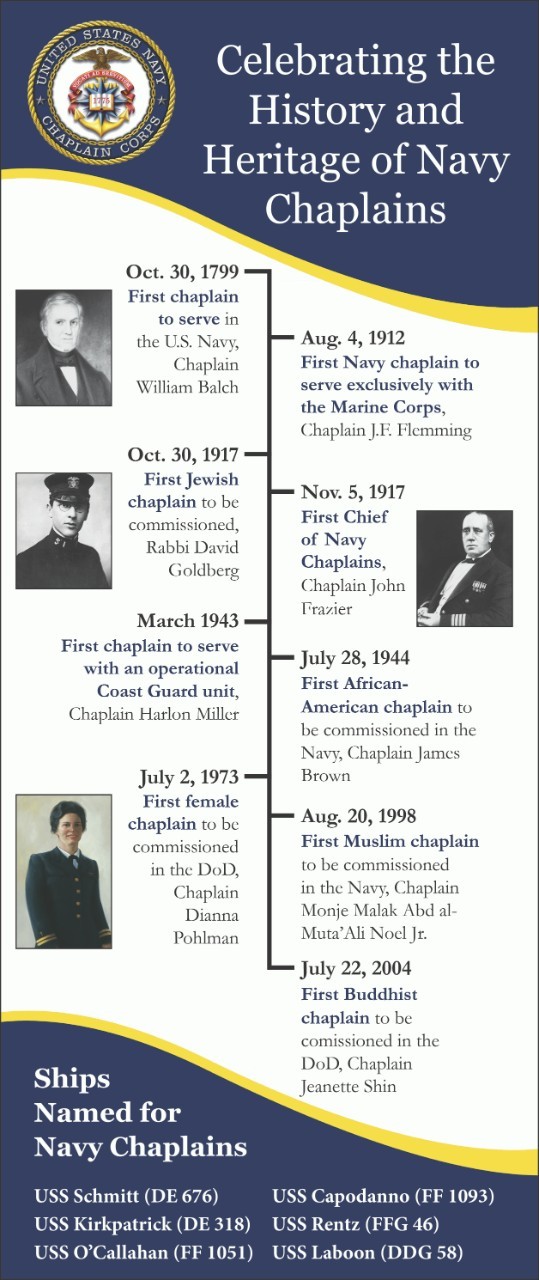

With troubles protecting U.S. interests on the high seas and after years of debate, the U.S. Navy was reestablished in 1794, and Congress authorized the building of six frigates. On Oct. 30, 1799, Reverend William Balch—son of the first Navy chaplain—was commissioned as the first Navy chaplain under the new Department of the Navy. Balch served aboard frigates Congress and Chesapeake. During the Navy’s early days, being an ordained clergyman was not a requirement. Most of the early chaplains were not ordained and were brought into the service more for their teaching abilities than their ecclesiastical accolades. Often, the chaplain was a layman appointed to that position. It was not until 1841 that general regulations mandated ordination and good moral character as requirements for appointment as a Navy chaplain. Most of the early Navy chaplains were Methodists and Episcopalians. These two denominations accounted for more than two-thirds of ordained Navy chaplains during the U.S. Navy’s first 80 years. Over time, other Christian denominations came to be represented, including Presbyterians, Unitarians, Lutherans, and Baptists. Reflecting the growing numbers of Catholics in the service, the Navy began commissioning priests as chaplains starting in 1888 with Father Charles H. Parks. During World War I, the Navy commissioned Rabbi David Goldberg as the first Jewish chaplain.

Not only have chaplains served in time of conflict, they have accompanied the Navy during some of its more notable exploration and scientific expeditions. The first U.S. Navy vessel (sloop-of-war Vincennes) to sail around the world, 1829–30, included a chaplain—Presbyterian Minister Charles Samuel Stewart. When Lt. Charles Wilkes took an expedition into the Pacific and to Antarctica from 1838–41, he was accompanied by Chaplain Jared Elliott. Later, Chaplains George Jones and Edmund Bittinger were part of Commodore Matthew Perry’s diplomatic missions to Japan in 1853 and 1854.

Notable changes have occurred within the Chaplain Corps over time. During the Civil War, chaplains were granted Navy ranks and authorized to wear the Navy uniform with those ranks and the Christian cross as their branch insignia. During the second decade of the 20th century, chaplains began to be regularly assigned to Marine Corps units. During World War I, the Chaplain Corps expanded from 40 chaplains to more than 200 by the time of the armistice in November 1918. In order to accomplish this, the Navy began to rely heavily upon its Naval Reserve force and naval militias. To oversee the expansion, Chaplain John B. Frazier was appointed as the first Chief of Chaplains.

Notable Navy chaplains who have served with distinction include Chaplain John L. Lenhart, who was the first Navy chaplain to die in combat when his ship, frigate Cumberland, was sunk by the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia (formerly USS Merrimack) on March 8, 1862. Chaplain John P.S. Chidwick, a Catholic priest, was one of the few survivors of the explosion and subsequent sinking of second-class battleship Maine. He distinguished himself by ministering to the dying and caring for the wounded. Chaplain Frazier, who later became Chief of Chaplains, stood alongside Commodore George Dewey on the bridge of cruiser Olympia during the Spanish-American War’s Battle of Manila Bay. Navy chaplains served in the trenches with Marines in France and during the pivotal Battle of Belleau Wood. Four chaplains—Albert Park, John J. Brady, H. A. Darche, and James D. MacNair—were awarded the Navy Cross for heroism while ministering in combat with Marines during the “Great War.” During World War II, chaplains who served with distinction included Commander Joseph T. O’Callahan, Commander George S. Rentz, Lt. (j.g.) Aloysius H. Schmitt, and Capt. Francis Lee Albert. Lt. Vincent R. Capodanno was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously during the Vietnam War.

Today, Navy chaplains continue to serve side by side with Sailors and Marines both on land and at sea. Navy chaplains provide a voice of encouragement, reason, and hope to thousands of naval personnel. From morning prayers to Sunday mass services to baptisms at sea, Navy chaplains support and uplift naval personnel who have chosen to serve their country. Currently the Navy Chaplain Corps boasts more than 800 Navy chaplains from more than 100 different faith groups, including Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and many more. Chaplains hold important leadership roles as well, including providing advice on ethical issues as part of the command staffs. Happy 248th Birthday, Navy Chaplain Corps!