Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

With the signing of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty on Aug. 9, 1842, the United States and Great Britain formally agreed to combat slave trade on the high seas. The treaty’s anti-slavery provision called for each nation to “prepare, equip, and maintain in service, on the coast of Africa, a sufficient and adequate squadron, or naval force of vessels … for the suppression of the slave trade.” The agreement resulted in the formation of the African Squadron that came equipped with warships and cutters. In 1843, the United States sent a total of four ships carrying 88 guns to West Africa. The flotilla accounted for roughly nine percent of the entire U.S. Navy at that time. The African Squadron participated in anti-slave patrols with the British until the start of the U.S. Civil War in April 1861. While on the anti-slave patrols, the squadron captured about 100 slave ships, and they represented the first international naval coalition established to combat human trafficking.

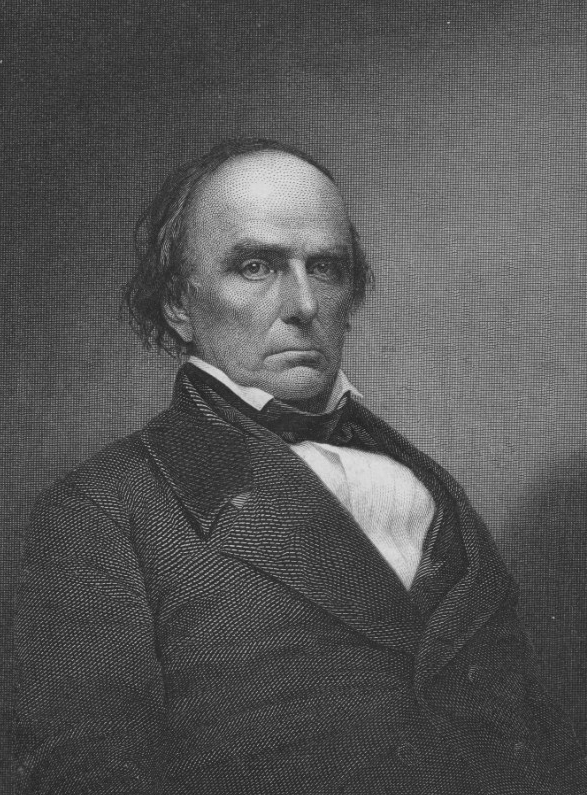

During Daniel Webster’s first term as the secretary of state, the primary foreign policy issues the United States had were with Great Britain. They included the northeastern borders of the United States, the involvement of American citizens in the Canadian Rebellion of 1837, and the suppression of international slave trade. The treaty ultimately resolved these issues. On April 4, 1842, British diplomat Lord Ashburton arrived in Washington, DC, as the head of a special mission to the United States. His first order of business was settling the border dispute between the United States and Canada. Other issues were added to the treaty to include the anti-slavery provision.

The treaty was a long time in the making. Several disputes had arisen from differing interpretations of the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolution. When these differences led New Brunswick officials to arrest some Americans in disputed areas, the state of Maine called out their militia and seized the territory in question—the Aroostock War. The incident dramatized the need for a border settlement. Webster and Ashburton agreed on a division of disputed territory, giving 7,015 square miles to the United States and 5,012 to Great Britain; agreed on the boundary line through the Great Lakes; and agreed on provisions for open navigation in various bodies of water. After the suppression of the rebellion in Canada, several participants fled to the United States where some Americans joined them. They occupied a Canadian island in the Niagara River and engaged a U.S. ship, Caroline, to resupply them. Canadian troops seized Caroline in a New York port, killing one crewman in the process, and set the ship free to drift over Niagara Falls. Later, Alexander McLeod, a sheriff who served in Ontario, crossed into New York and bragged that he had participated in the seizure of Caroline, and had killed the American Sailor. McLeod was later arrested. Great Britain maintained that McLeod had acted as a member of the British forces and that it would take responsibility for his actions. Should he be executed, it would mean another war with Great Britain.

The U.S. government agreed that McLeod could not be tried for actions committed under orders of the British government, but it was not capable of compelling the state of New York to release him. New York would not back down and tried McLeod. He was ultimately acquitted. Webster and Ashburton agreed on the principles of international law involved and exchanged conciliatory statements. The United States enacted a law allowing federal judges to discharge any person proved to have acted under instruction of a foreign power. The United States and Canada later agreed on an extradition treaty. However, Webster would not agree to British inspection of U.S. ships suspected of carrying slaves, but did agree that U.S. warships would be maintained off the coast of Africa to search suspected slavers flying the American flag.

Constitution Defeats Guerriere

On Aug. 19, 1812, while sailing off the coast of Nova Scotia, frigate Constitution, commanded by Capt. Isaac Hull, captured the powerful, 49-gun British frigate Guerriere. It was a dramatic victory for the young American Navy and Constitution. In only half an hour, the United States “rose to the rank of a first-class power.” Constitution’s victory provided confidence and fresh courage that ultimately strengthened a young nation during the War of 1812. It was during this engagement, Constitution earned her nickname “Old Ironsides” as Sailors reported seeing cannonballs bounce off her hull.

The engagement began with Guerriere about a month earlier when (after Hull read to his crew the declaration of war between the United States and Great Britain) Constitution set sail to rejoin the North Atlantic Squadron. A few days after she was underway, Constitution sighted five ships on the horizon that the crew believed to be the American squadron, but ultimately was identified as a powerful British squadron that included Guerriere and another frigate Shannon. As Constitution came to within range, the British squadron opened fire. Hull cleverly towed, wetted sails, and kedged to draw the ship slowly ahead of her pursuers. For two days, all hands were on deck in a desperate attempt that ultimately led to their escape. Then, on Aug. 19, Constitution again sighted Guerriere. As the ships drew nearer, Guerriere opened fire on Constitution, however, the rounds either fell harmlessly into the ocean or glanced off the ship. Hull subsequently gave the order to fire on the British ship that ultimately destroyed Guerriere's mizzen mast, damaged her foremast, and cut away most of her rigging. Both crews tried to board each other’s ships, but heavy seas prevented it. As the ships began to separate, Guerriere desperately fired point blank into the cabin of Constitution, but the fires were quickly extinguished. Guerriere was dead in the water. The British ship struck her flag and the crew of Constitution boarded the enemy ship, but it was in such bad condition that it was ultimately burned and the crew were taken as prisoners.

During the war, Constitution captured, burned, or sent in as prizes nine merchantmen and five ships of war. Another notable conquest for Constitution occurred about six months after her victory over Guerriere when she encountered 38-gun frigate Java off the coast of Brazil. Despite the loss of her wheel early in the fighting, Constitution’s superior gunnery shattered the enemy's rigging, eventually dismasting Java, and mortally wounding her captain. Java was so badly damaged that she, too, had to be burned.

After the war, Constitution underwent extensive repairs for the next six years in Boston. In May 1821, she returned to commission and served as flagship of the Mediterranean Squadron, where she continued to guard American shipping lanes through July 1828. In 1830, Constitution was found to be unseaworthy and Congress considered selling or scraping the ship, but public sentiment elicited instead an appropriation of money for reconstruction that began at Boston in 1833. Two years later, Constitution returned to commissioned status and she served in a variety of missions for the next two decades. In March 1845, Constitution began a memorable 30-month circumnavigation of the globe. In the fall of 1848, Constitution returned as flagship of the Mediterranean Squadron, and after being decommissioned briefly in 1851, patrolled the west coast of Africa for slavers until June 1855. Constitution was then decommissioned again for another five years.

In August 1860, Constitution was assigned to train midshipmen at Annapolis, Maryland, and in 1871, underwent rebuilding at Philadelphia before she was recommissioned again in July 1877 to transport goods to the Paris Exposition. Once she returned, Constitution returned to duty as a training ship before she was decommissioned and towed to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to serve as a receiving ship. In 1897, she made way to Boston to celebrate her centennial, but remained in decommissioned status. Public sentiment once again saved the ship from destruction in 1905, and she was partially restored as a museum ship. Twenty years later, she was completely renovated with the financial assistance of numerous donors.

On July 1, 1931, Constitution returned to commissioned status. The following day, Constitution hoisted her sails for a tour of 90 U.S. ports along the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coasts, where thousands of Americans saw at first hand one of history's greatest fighting ships. On July 23, 1954, Congress authorized the Secretary of the Navy to restore Constitution “as far as may be practicable” back to her original condition, but not for active service. She was later named a National Historic Landmark in 1960 due to her extraordinary history. On July 21, 1997, she set sail for the first time in 116 years to commemorate her 200th birthday, and again in August 2012 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812. Constitution was designated America’s Ship of State in 2009. From 2015–2017, Constitution was renovated by Naval History and Heritage Command’s Detachment Boston, which included new copper sheathing on her lower hull and other important upgrades.

Today, the Sailors of Constitution, in partnership with the NHHC’s Detachment Boston, the USS Constitution Museum, and the National Park Service, work to preserve, protect, and promote Constitution for the people of the United States and the world as a living link to the Sailors and Marines of the past, present, and future. Annually, more than 500,000 people walk across Constitution’s decks. She remains the world’s oldest commissioned warship afloat, and the world’s oldest vessel that can still sail under its own power.

Operation Dragoon

After weeks of Allied naval and air force bombardment, Operation Dragoon began on Aug. 15, 1944, which was the Allied invasion of southern France. U.S. Eighth Fleet, commanded by Vice Adm. Henry K. Hewitt, and the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet provided the amphibious lift, bombardment/fire support, mine warfare, naval air support, and special operations forces designated as the Western Task Force. By the time the operation kicked off, the Germans were already demoralized and disorganized by weeks of bombardment, and except for one strongpoint that was eventually neutralized by a B-24 Liberator air strike, put up little resistance. By the evening of Aug. 17, the surviving German forces were in full retreat up the Rhône Valley, continually harassed by French resistance fighters. German air attacks on the landing forces were mostly ineffective, although an air-launched Henschel Hs-293 guided bomb sank LST-282 on Aug 15. On Aug. 19, U.S. Navy F6F Hellcats and Royal Navy Seafires, on an armed reconnaissance mission, shot down five enemy bombers near Toulouse, to the west of the Dragoon landing areas.

Likewise, the response by already weak German naval forces in the Mediterranean was negligible. A German torpedo boat flotilla based at Genoa, which could have sortied against the Western Task Force, remained in port and out of the fight. However, two German patrol vessels that engaged the Allies were sunk by USS Somers (DD-381) on Aug. 15 off the island of Port-Cros. On Aug. 17, to the northeast of the landing area off La Ciotat, USS Endicott (DD-495), PT boats, and gunboats of the U.S. Navy and British special operations forces were staging diversion operations when they were attacked by a German corvette and a patrol vessel. Although the Germans concentrated their fire on Endicott, and despite being outgunned, Endicott, commanded by Medal of Honor recipient Lt. Cmdr. John D. Bulkeley, emerged victorious.

Following consolidation of the beachhead, French forces headed southwest to capture Toulon and Marseille. In Toulon, they encountered heavy German resistance, but it was overcome by Aug. 26. In Marseille, German forces were hassled by the French resistance that undercut the enemy’s command and control operations. By Aug. 29, the city was in Allied hands. Western Task Force ships provided gunfire support, targeting the old, but very solid, port fortifications. In both cities, the Germans were able to destroy or mine portions of the port facilities. At Marseille, Marine detachments of USS Augusta (CL-31) and USS Philadelphia (CL-41) accepted the surrender of the German units defending the Frioul islands outside of the city’s harbor.

Operation Dragoon (originally dubbed Anvil) was first discussed at the Allied conference in Tehran in December 1943. The conference was the first time President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin met in person. At the conference, the three leaders and their staffs debated the operational roster for 1944. All approved of Operation Overlord: Invasion of Normandy. Stalin also promised a summer offensive on the Eastern Front (Operation Bagration) and Churchill wanted to advance in the Mediterranean, preferably the Balkans. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, with Roosevelt’s backing, pushed for the invasion of southern France. Although Churchill was doubtful and Stalin supported the operation, the three agreed the best way to support Overlord was the invasion of southern France. However, the consensus surrounding Anvil quickly vanished. Churchill argued that the invading force would get bogged down on the beach, and due to the need to supply the beachhead at Anzio, Anvil was dropped. Still, the American general in charge of planning for Anvil, Army Gen. Jacob Devers, continued to prepare despite the cancellation of the operation. However, when the landings on Normandy were deemed a success, the Allies had enough shipping capacity to undertake another amphibious operation and the plan for Anvil was nearly complete. It called for the American and French armies to land just east of Marseille and Toulon and capture them. The two important port cities would increase Allied supply capacity on the French mainland. Although Churchill still opposed the operation, the Americans prevailed and the operation was a go. It was renamed Dragoon on Aug. 1 for security reasons.

First Naval Aviation Medal of Honor Recipient

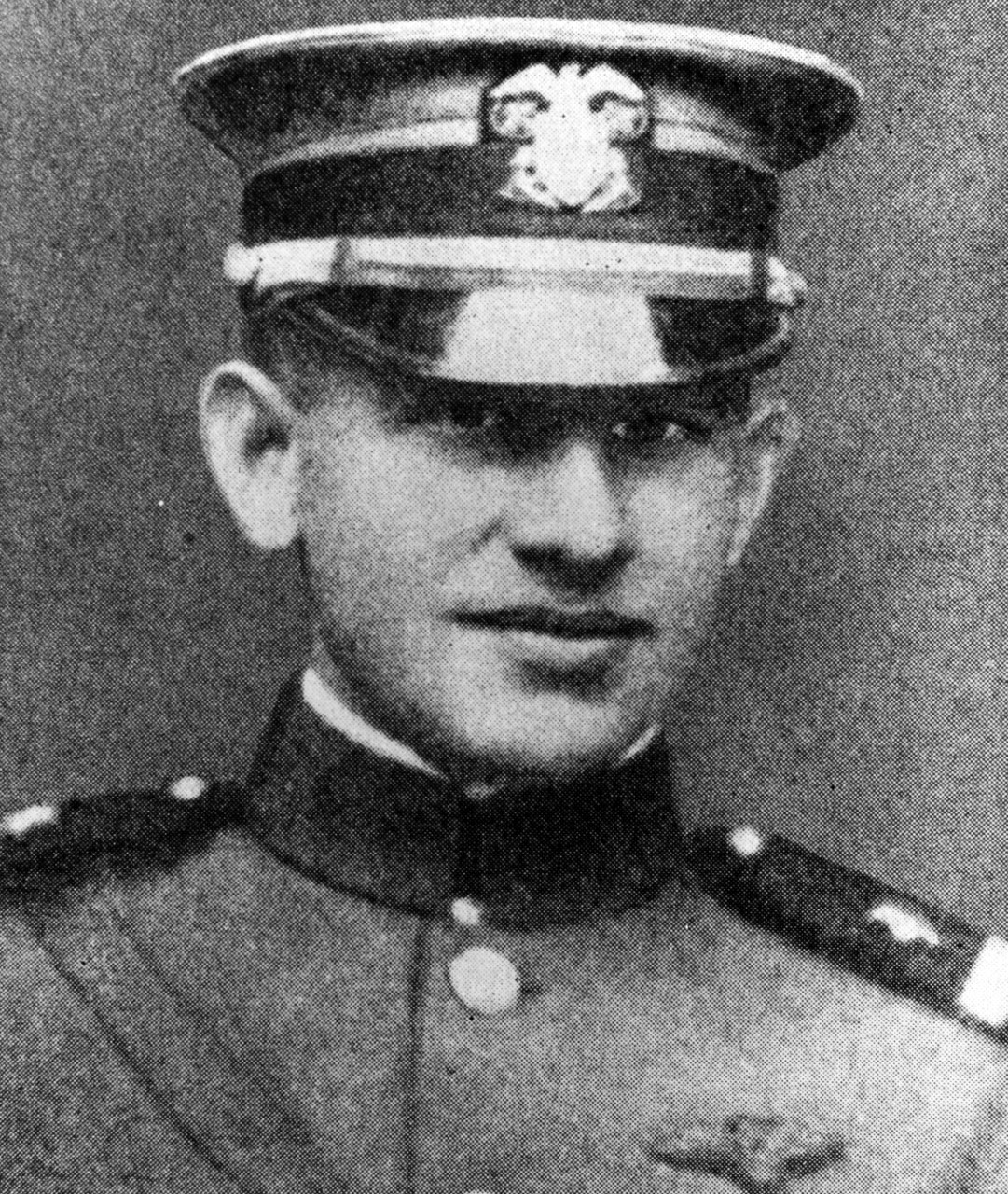

On Aug. 21, 1918, during World War I, enlisted pilot Charles H. Hammann landed his Navy seaplane in the Adriatic Sea about three miles off the coast of Pola and rescued Ensign George H. Ludlow, whose aircraft was shot down by Austro-Hungarian forces (now Croatia). At the time, Austro-Hungarian forces were allies of Germany and had threatened to execute any downed aviators flying missions over their territory. On that day, five U.S. Navy Macchi M.5 seaplanes were flying their first combat mission over a heavily-defended port and a naval base at Pola. They were escorting two Italian seaplanes on a leaflet drop mission. Five enemy fighters and two seaplanes engaged the Americans and Italians. During a dogfight, Ludlow’s aircraft was hit and his aircraft was so damaged that he had no choice but to land it in the ocean where he was at great risk of capture. As Ludlow prepared to destroy his aircraft, Hammann landed right next to Ludlow. Although Hammann’s aircraft was also damaged in the dogfight and his plane was designed to only carry one person, he managed to get airborne as Ludlow’s aircraft sank. Avoiding additional Austro-Hungarian search planes, Hammann managed to make his way to safety at Porto Corsini, Italy.

Hammann, a native of Baltimore, Maryland, later became the first U.S. aviator—of any service—to receive the Medal of Honor for his actions on that day. Ludlow was awarded the Navy Cross. Hammann was also commissioned an ensign in October 1918. Unfortunately, Hammann was killed on June 14, 1919, when he crashed his aircraft at Langley, Virginia. A destroyer, USS Hammann (DD-412), and a destroyer escort, USS Hammann (DE-131), were named in his honor. His namesake destroyer was sunk by a Japanese submarine on June 6, 1942, while she was rendering aid to the damaged USS Yorktown (CV-5) following the Battle of Midway. His namesake destroyer escort was commissioned about a year later and served for the remainder of World War II. For more naval aviation firsts, visit NHHC’s website.