USS Washington (BB-56)

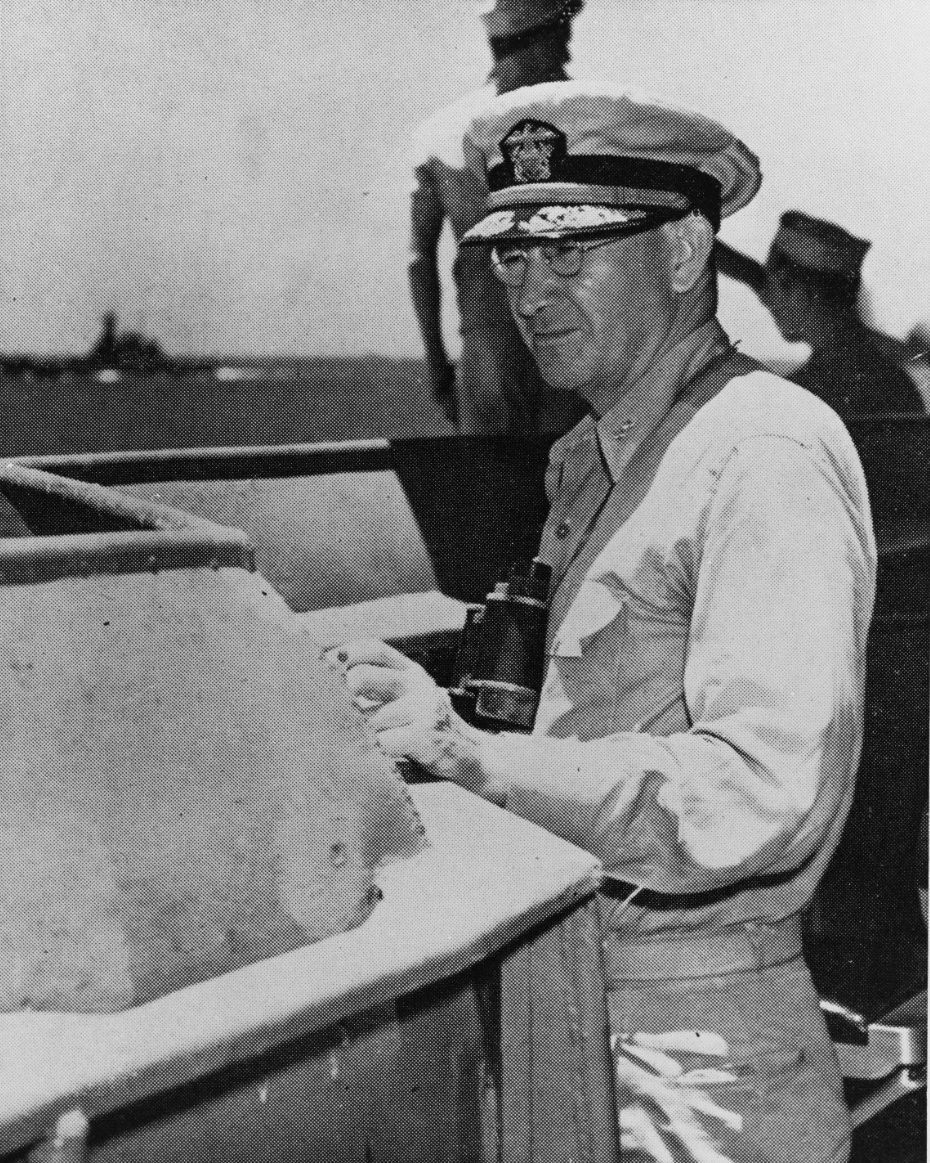

Battleship USS Washington (BB-56), named to honor the 42nd state, was commissioned at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 15 May 1941 with Captain Howard H. J. Benson in command. After shakedown and underway training, Washington continued underway operations along the eastern seaboard and into the Gulf of Mexico until the United States entry into World War II following the Pearl Harbor attack on 7 December 1941. On 26 March 1942, Washington was assigned as flagship of Task Force 39 under the flag of Rear Admiral John W. Wilcox as she sailed for the British Isles to reinforce the British Home Fleet. While steaming through relatively heavy seas the following day with USS Wasp (CV-7), USS Wichita (CA-45), USS Tuscaloosa (CA-37), and two destroyers, the “man overboard” alarm sounded onboard Washington and a quick muster revealed Wilcox was missing. Tuscaloosa maneuvered and dropped life buoys while the two destroyers began to search in Washington’s wake. Despite the foul weather, aircraft from Wasp also launched to join the search for the missing flag officer. Lookouts briefly spotted Wilcox’ body in the water some distance away, face down, but were unable to pick him up due to the weather. One of the aircraft launched from Wasp to assist in the search crashed killing its two-man crew. The admiral’s body was never recovered. Shortly after noon, the search was abandoned and the next senior officer, Rear Admiral Robert C. Geffen, took command of the task force as they continued to England. On 4 April, the task force joined the British Home Fleet at Scapa Flow under the command of Sir John Tovey. Washington engaged in maneuvers with units of the Home Squadron into late April before the task force was redesignated Task Force 99 with Washington as the flagship. On 28 April, the task force was underway to protect convoys running lend-lease supplies to Murmansk in the Soviet Union. Washington continued to operate with the Home Squadron until late July before she set sail for the New York Navy Yard for a thorough overhaul.

After work on Washington was complete, she set sail on 23 August for Pacific waters where she would join Task Force 17 arriving 15 September. Washington then proceeded to Noumea, New Caledonia, where she supported the ongoing Solomons Campaign, providing escort services for various reinforcement convoys proceeding to and from Guadalcanal. By mid-November, the situation for the Allies was becoming dire, who were now down to one aircraft carrier, USS Enterprise (CV-6), after the loss of Wasp in September and USS Hornet (CV-8) in October. In addition, Japanese surface ships pounded Henderson Field on Guadalcanal with regularity. However, the Japanese usually made their moves at night, because Allied aircraft ruled the sky during the day. That meant the Allies had to transport their replenishment and reinforcement convoys during daylight hours. Washington provided protection for those convoys into mid-November 1942.

On 13 November, Washington learned that three large groups of Japanese ships were headed towards Guadalcanal. At sunset—led by Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee, Jr.—Washington, USS South Dakota (BB-57), and four destroyers steamed for Savo Island to be in position to intercept the Japanese convoy and its protection force. The American ships, designated Task Force 64, reached a point about 50 miles south-by-west from Guadalcanal late in the forenoon of 14 November and spent much of the remainder of the day trying, unsuccessfully, to avoid being spotted by Japanese reconnaissance planes. At midnight on 15 November, Washington’s radar picked up a contact bearing to the east of Savo Island. Approximately 15-minutes later, Washington opened fire with her 16-inch main battery. The fourth Battle of Savo Island was underway.

For the next few minutes, Washington hurled 42 rounds aimed at Japanese light cruiser Sendai. Simultaneously, the battleship's 5-inch battery engaged another enemy ship that was attacking South Dakota. Later, during the course of the battle, Washington engaged battleship Kirishima in the first head-to-head confrontation of battleships during the Pacific War. In just seven minutes, Washington, using radar-directed gunfire, sent 75 rounds of 16-inch and 107 rounds of 5-inch scoring at least nine hits with her main battery and about 40 with her 5-inch battery. The enemy battleship was left burning and exploding. Subsequently, Washington's 5-inch battery went to work on other targets spotted by her radar “eyes.”

The battle was not, however, one-sided. Japanese gunfire proved devastating to the four destroyers of the task force as did the dreaded and effective “long lance” torpedoes. USS Walke (DD-416) and USS Preston (DD-379) both took numerous hits of all calibers and sank. USS Benham (DD-397) sustained heavy damage to her bow, and USS Gwin (DD-433) sustained shell hits aft. South Dakota had maneuvered to avoid the burning destroyers, but soon found herself the target of the entire Japanese bombardment group. South Dakota deployed salvos at the enemy, as did Washington, however, South Dakota suffered several hits and withdrew. Washington steamed north to draw fire away from her crippled sister battleship and the two heavily damaged destroyers, Benham and Gwin. Initially, the remaining ships of the Japanese bombardment group gave chase to Washington, but broke off contact when discouraged by Washington’s heavy guns. Accordingly, the enemy withdrew under cover of a smokescreen. Washington emerged from the battle unscathed, however, South Dakota sustained heavy damage to her superstructure. She lost 38 men and another 60 were wounded as well. The Japanese lost a battleship and the destroyer Ayanami. After the pivotal battle, Washington remained in South Pacific waters until late April 1943 protecting carrier groups and task forces engaged in the ongoing Solomons Campaign. She returned to Hawaiian waters in May 1943 for a well-deserved overhaul at Pearl Harbor.

After alterations and repairs were complete, Washington joined a convoy on 27 July to form Task Group 56.14 bound for the South Pacific. Detached on 5 August, Washington reached Havannah Harbor, at Efate, in the New Hebrides two days later. She then operated out of Efate until late October. On 15 November, Washington joined Rear Admiral Charles A. Pownall's Task Group 50.1 that proceeded to the Gilbert Islands to join in the daily bombardment of Japanese positions in the Gilberts and Marshalls. From 19–20 November, the task group attacked Mili and Jaluit in the Marshalls. On 20 November, Army, Navy, and Marine forces landed on Tarawa and Makin in the Gilberts. For the remainder of the year and into the next year, Washington continued to provide bombardment support for several operations with several task forces. On 1 February 1944, however, inevitable misfortune reared its head as Washington, while maneuvering in pitch black darkness, rammed USS Indiana (DD-58). She cut across Washington's bow while dropping out of formation to fuel escorting destroyers. Washington sustained 60 feet of crumpled bow plating. Subsequently, after temporarily reinforcing the damaged bow at Majuro, Washington set sail for the Hawaiian Islands, and continued on to the Puget Sound Navy Yard in Bremerton, Washington, for a new bow.

On 30 May, Washington arrived back at Majuro as once again Lee’s flagship. On 7 June, Washington joined Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher’s Task Force 58. Washington supported the air strikes that pounded enemy defenses in the Marianas on the islands of Saipan, Tinian, Guam, Rota, and Pagan. Later that month, Washington, six other battleships, four heavy cruisers, and 14 destroyers steamed to cover the aircraft carriers as the Battle of the Philippine Sea had commenced. The tremendous fire power of the American force caused heavy loss of Japanese aircraft—commonly referred to as the Marianas Turkey Shoot. During the massive battle, the Japanese launched 373 aircraft, but only 130 returned. In addition, 50 land-based bombers from Guam were shot out of the sky. More than 300 American carrier planes were involved in the aerial action. Their losses amounted to comparatively few with only 23 shot down, and six lost operationally. Not a single ship from Mitscher’s Task Force 58 was lost. Comparatively, the Japanese lost two carriers, Taiho and Shokaku.

After the Japanese suffered defeat at the Battle of the Philippine Sea, Washington continued screening duties to the south and west of Saipan. On 6 August, Washington detached, along with other ships in the task force, to refuel and replenish at Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshalls where they would remain until the end of the month. On 30 August, they departed headed for, first, the Admiralty Islands, and ultimately, the Palaus.

Washington’s heavy guns supported the invasion of Peleliu and Angaur in the Palaus. In addition, she supported the carrier strikes on Okinawa on 10 October, on northern Luzon and Formosa from 11–14 October, as well as the Visayan air strikes on 21 October. From 5 November–17 February 1945, Washington served as a vital part of the fast carrier striking forces, supporting raids on Okinawa, China, and even Tokyo. From 19–22 February, Washington’s big guns supported the landings on Iwo Jima, and on 24 March, and again on 19 April, Washington provided her support to the shellings of Japanese positions on the island of Okinawa.

On 23 June, Washington arrived at the Puget Sound Navy Yard for refit. Washington would never see combat action again. On 2 September, the instrument of surrender was signed by representatives of the Allied and Japanese governments onboard USS Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay. After serving as part of the “Magic Carpet” operation and participating in Navy Day celebrations, the battleship was placed out of commission, in reserve, on 27 June 1947. She remained inactive until 1 June 1960 when she was struck from the Navy list and sold for scrap.

Washington earned 13 battle stars for her gallant service during World War II in operations that carried her from the Arctic Circle to the western Pacific.

*****

Suggested Reading

- Surface Navy

- Radar and Sonar

- H-Gram 012-4: Guadalcanal, 1942—The Battle of Saturday the 14th

- Guadalcanal Proved Experimentation Works

- H-Gram 013-1: The Battle of Tassafaronga—Night of the Long Lances

- H-Gram 020-2: Central Solomon Islands Campaign: Kula Gulf, Kolombangara, Vella Gulf, PT-109, and Battles with No Names

- H-026-1: Operation Flintlock—The Invasion of Kwajalein, 31 January 1944

- H-Gram 032-1: Operation Forager and the Battle of the Philippine Sea

- H-Gram 044-1: Operation Iceberg—Background to the Battle for Okinawa

- U.S. Navy Vessels in the Battle of the Philippine Sea and Marianas Operational Area

- Naval Battle of Guadalcanal: Historical Summary

Selected Imagery

Task Group 38.3 enters Ulithi anchorage after strikes in the Philippines Islands, 12 December 1944. Ships include USS Langley (CVL-27), USS Ticonderoga (CV-14), USS Washington (BB-56), USS North Carolina (BB-55), USS South Dakota (BB-57), USS Santa Fe (CL-60), USS Biloxi (CL-80), USS Mobile (CL-63), and USS Oakland (CL-95). National Archives photograph, 80-G-301352.

Rear Admiral John W. Wilcox, pictured as a lieutenant commander, was onboard his flagship, USS Washington (BB-56), on 26 March 1942 as she sailed in heavy seas for the British Isles to reinforce the British Home Fleet. The “man overboard” alarm sounded onboard Washington and a quick muster revealed he was missing. A search by Task Force 39 was unable to recover his body. Two naval aviators also lost their lives in the search for the missing flag officer. Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 119479.