Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

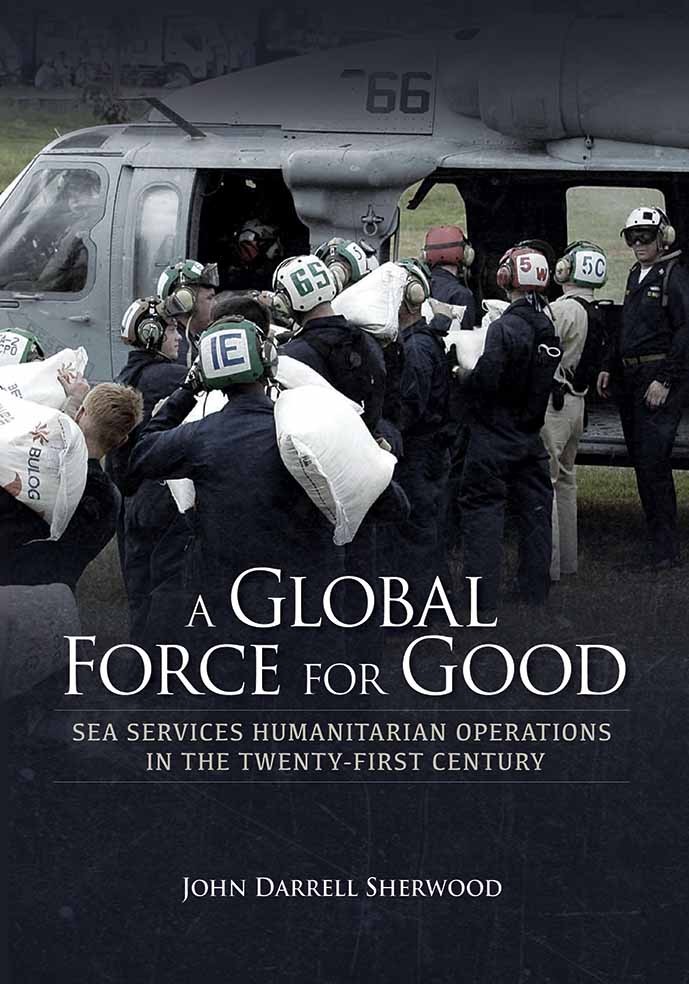

A Global Force for Good

Since 1900, it is estimated that more than 32 million people worldwide have lost their lives due to natural disasters. In response, the U.S. military is usually one of the first to be called upon to help deal with these tragedies. In his book, A Global Force for Good, Naval History and Heritage Command’s John Sherwood examines the response of the U.S. Navy and its partners to three of the most destructive disasters in recent history: the 2004 earthquake and tsunami in Indonesia; Category 5 Hurricane Katrina in 2005; and Japan’s triple disaster in 2011, which included a 9.0 magnitude earthquake followed by a tsunami and nuclear incidents in the Tōhoku region. Based on original sources and numerous interviews, Sherwood not only explores a topic rarely examined by historians, but crafts a vivid and compelling narrative. His book was recently published and is available for free as a 508-compliant PDF on NHHC’s website.

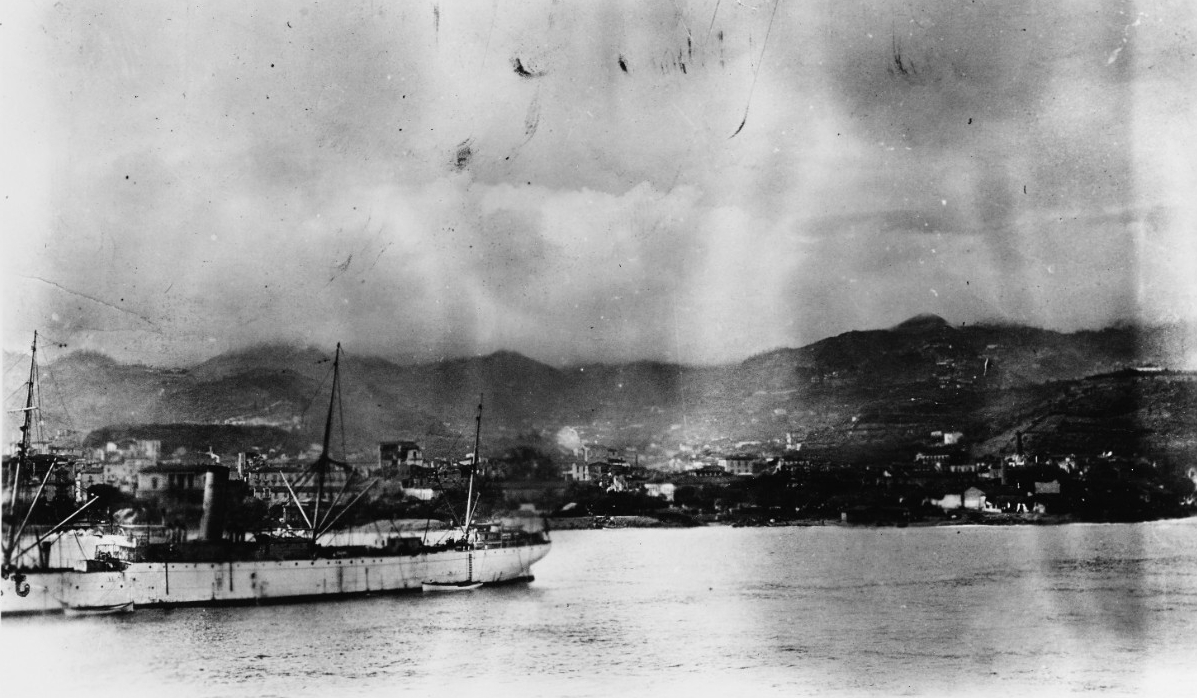

The Navy has actively responded around the world to natural disasters since the beginning of the 20th century in its humanitarian efforts. On Dec. 28, 1908, a magnitude 7.1 earthquake hit the Strait of Messina. The massive tremor leveled the Sicilian city, destroying more than 90 percent of its buildings and killing more than 75,000 people. Ten minutes later, a nearly 40-foot tsunami struck the coasts on both sides of the strait, killing an additional 2,000 people. It was the most destructive natural disaster in terms of casualties to strike Europe in modern history. That same day, a fleet of 16 U.S. battleships and accompanying escorts, known as the Great White Fleet, was coaling in Port Said, Egypt, after transiting the Suez Canal. It was preparing to make port calls at various European destinations before completing its historic cruise around the globe. After hearing of the tragedy, Rear Adm. Charles S. Sperry, the fleet’s commander, deployed his 2nd Division to Italy to provide assistance. Battleships Connecticut (BB-18) and Illinois (BB-7) and three support ships arrived on Jan. 10, 1909. They soon began delivering supplies to towns on both coasts and sending parties of Sailors ashore to help rebuild structures, clear rubble, and provide general assistance. Cumulatively, the efforts of the Great White Fleet during the 10-day operation saved thousands of Italian lives and created goodwill between the U.S. Navy and the Italian people. King Victor Emmanuel met with Rear Adm. Sperry in Rome to thank him for the American assistance, and the Marquis del Carretto, who was also the mayor of Naples, commended him for the efforts of his fleet in helping the Italian people in wake of the tragedy. The Great White Fleet’s response to the Messina earthquake and tsunami was the first major U.S. Navy foreign natural disaster response operation.

In the aftermath of the Messina incidents, the worst natural disasters in terms of human loss were the 1931 Yangtze-Huai River floods in China, which killed more than 3.7 million, and the 1928 drought in China, which caused an estimated 3 million deaths. In the 21st century, two disasters alone have together claimed close to 400,000 lives—the 2004 earthquake and tsunami in Southeast Asia, and the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Wherever a large-scale natural disaster occurs, it is inevitable that foreign governments and international organizations will request help from the U.S. armed forces. No matter how developed a country might be, there will always be a gap between the disaster response needs of an affected region and the local resources available to meet those needs. Neither local communities nor international organizations and non-governmental organizations have the logistical means to rapidly deliver water, food, and emergency medicine to areas affected by a large-scale natural disaster. The U.S. armed forces (in particular its air and sea services) are often one of the first to be called upon because of their ability to respond in a timely and meaningful way. The U.S. Navy has significant disaster response capabilities forward deployed in most of the world’s most disaster-prone regions. Above all, the Navy has the logistical means to deliver extensive amounts of aid nearly anywhere on earth and operate for long periods of time in areas completely lacking infrastructure. This is a central premise of Sherwood’s book. Check out this very informative book today!

9/11 Terrorist Attacks

On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, 19 terrorists from the extremist Islamist group al Qaeda hijacked four commercial aircraft and crashed two of them (American Airlines Flight 11 and United Airlines Flight 175) into the North and South Towers of the World Trade Center complex in New York. A third plane (American Airlines Flight 77) crashed into the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia. After learning about the other attacks, passengers on the fourth hijacked plane (United Airlines Flight 93) fought back against the hijackers and the plane was ultimately crashed into an empty field in western Pennsylvania about 20 minutes by air from Washington, DC. The Twin Towers subsequently collapsed due to the damage from the impacts and ensuing fires. Nearly 3,000 people from 93 different countries lost their lives in the attacks, with most of the fatalities from the attacks on the World Trade Center. The Pentagon lost 184 civilians and service members. It was the worst attack on American soil since the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

In the aftermath of the attacks, rescue operations began almost immediately. More than 400 police officers and firefighters lost their lives on that fateful day as they rushed into the Twin Towers in an attempt to rescue people trapped inside. On that morning, President George W. Bush was visiting a second grade class in Sarasota, Florida, when his chief of staff, Andrew Card, whispered in his right ear, “A second plane hit the second tower. America is under attack.” To keep the President safe, he was hopscotched across the country on Air Force One, landing in Washington, DC, that evening. At 8:30 p.m., he addressed the nation: “We will make no distinction between the terrorists who committed these acts and those who harbor them.”

Soon after the attacks, evidence gathered by the United States intelligence community soon convinced most other governments that al-Qaeda was responsible for the attacks. The group’s leader, Osama bin Laden, had made numerous anti-American statements and had been implicated in previous terrorist strikes against American citizens. Al-Qaeda was headquartered in Afghanistan and had a close relationship with the country’s rulers, the Islamic Taliban group. After the Taliban refused to extradite bin Laden and terminate all al-Qaeda activity, NATO Article 5 was invoked, allowing the alliance’s members to respond collectively in self-defense. On Oct. 7, the U.S. and allied military forces launched an attack against Afghanistan—Operation Enduring Freedom. Within months, thousands of militants were killed or captured and Taliban and al-Qaeda leaders were driven into hiding. In addition, the U.S. government exerted great effort to track down al-Qaeda agents and sympathizers throughout the world and made combating terrorism the focus of U.S. foreign policy. Meanwhile, security measures in the United States were tightened considerably at places such as airports, government buildings, and sports venues. To help facilitate the domestic response, Congress passed the Patriot Act, which temporarily expanded the search and surveillance powers of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other law enforcement agencies. In addition, the Department of Homeland Security was established.

Meanwhile, on the battlefield in Afghanistan, military operations devastated the Taliban regime and undermined bin Laden’s al-Qaeda network. By December 2001, most initial campaign goals had been achieved and combat operations shifted to the mountains of eastern Afghanistan, where isolated al-Qaeda and associated Taliban militants had fled. Several months later, U.S. forces launched Operation Anaconda, the largest ground battle of the war. Hundreds of Taliban and al-Qaeda fighters fled into Pakistan, with bin Laden likely among them. It would not be until May 2, 2011, when U.S. Navy SEALS launched a nighttime raid on bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, that the al Qaeda leader was killed. Operation Enduring Freedom officially ended on Dec. 28, 2014, although coalition forces remained on the ground to assist with training Afghan security forces until the departure of U.S. forces in August 2021. Thirteen service members and more than 100 Afghan civilians were killed outside the Kabul Airport on Aug. 26, 2021, by a terrorist attack during the chaotic withdrawal. Among those killed were 11 Marines, one Soldier, and Navy Petty Officer Third Class Maxton W. Soviak.

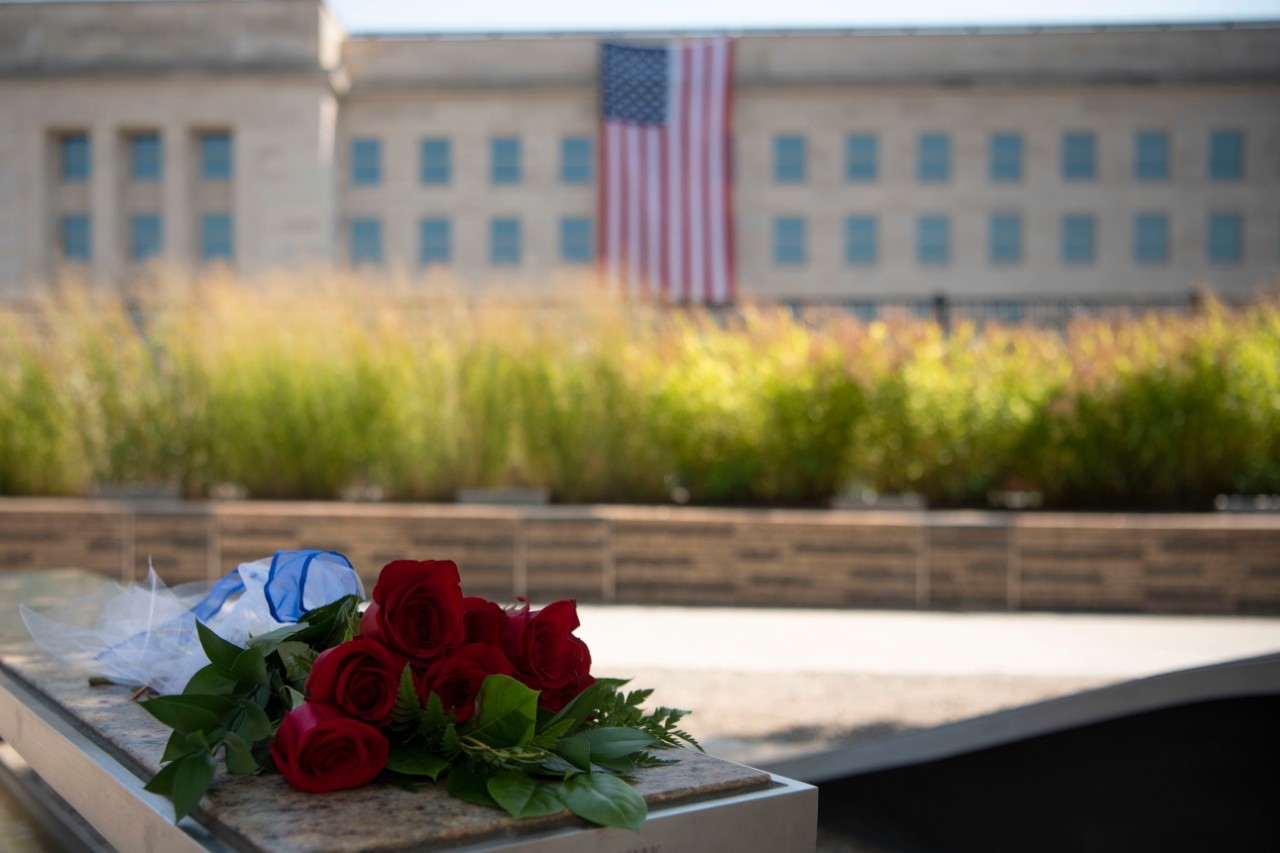

Since the 9/11 attacks, several monuments have been constructed around the United States and in other countries such as England, Italy, and Israel. The National September 11 Memorial and Museum in New York opened in May 2014. It pays tribute to those killed in the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11 and during a previous terrorist attack on Feb. 26, 1993. The memorial consists of two reflecting pools in the footprints of the Twin Towers. The 9/11 Pentagon Memorial in Arlington is a permanent outdoor memorial that pays tribute to the 184 who were killed in the terrorist attack, and the Flight 93 National Memorial in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, pays tribute to the 40 passengers and crew who gave their lives so that the terrorists that hijacked their plane couldn’t harm anyone else.

Inchon Landing

On Sept. 15, 1950, during the Korean War, after several days of preliminary naval gunfire and air bombardment, U.S. Marines landed at Inchon, 100 miles south of the 38th parallel and just 25 miles from Seoul. Code-named Operation Chromite, the location of the invasion had been criticized as too risky. However, General of the Army Douglas A. MacArthur, the U.S. commander-in-chief, Far East, and commander-in-chief, United Nations Command, persuaded his superiors in Washington, DC, to approve his plan for an amphibious assault at Inchon behind enemy lines. By the early evening, Marines had overcome moderate resistance and secured Inchon. The landings cut North Korean forces in two, and the U.S.-led UN force pushed inland to recapture Seoul, the South Korean capital that had fallen to the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) in June. Allied forces then converged from the north and the south, devastating the NKPA and taking 125,000 enemy troops prisoner. Although Seoul was retaken in wake of the Inchon invasion, it would change hands six more times before an armistice was signed on July 27, 1953, in the first major conflict of the Cold War.

The Korean War began on June 25, 1950, when 90,000 Communist soldiers stormed across the 38th parallel, catching Republic of Korea forces and the U.S. Eighth Army troops completely off guard and propelling them into a retreat down the Korean peninsula. Two days later, President Harry S. Truman announced the United States would intervene, and on June 28, the UN approved the use of force against North Korea. On June 30, President Truman agreed to send U.S. ground forces to Korea, and on July 7, the Security Council recommended that all UN forces sent to Korea be put under U.S. command. The next day, Gen. MacArthur was named commander of all UN forces in Korea. In the opening months of the war, U.S.-led UN forces rapidly advanced against the North Koreans, but the Chinese intervened in the war, throwing the allies into another southern retreat. In April 1951, President Truman relieved MacArthur because of his public comments that went against Truman’s stated war policy. Truman feared MacArthur’s comments would draw the Soviet Union into the war. By May 1951, the North Koreans were pushed back to the 38th parallel and the battle lines remained mostly stagnant for the remainder of the war.

Forty-two U.S. Marines and seven Sailors were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions during the Korean War. Approximately 150,000 troops from South Korea, the United States, and participating UN nations were killed in the conflict, and as many as 1 million South Korean civilians perished. An estimated 800,000 Communist soldiers were killed, and more than 200,000 North Korean civilians died.

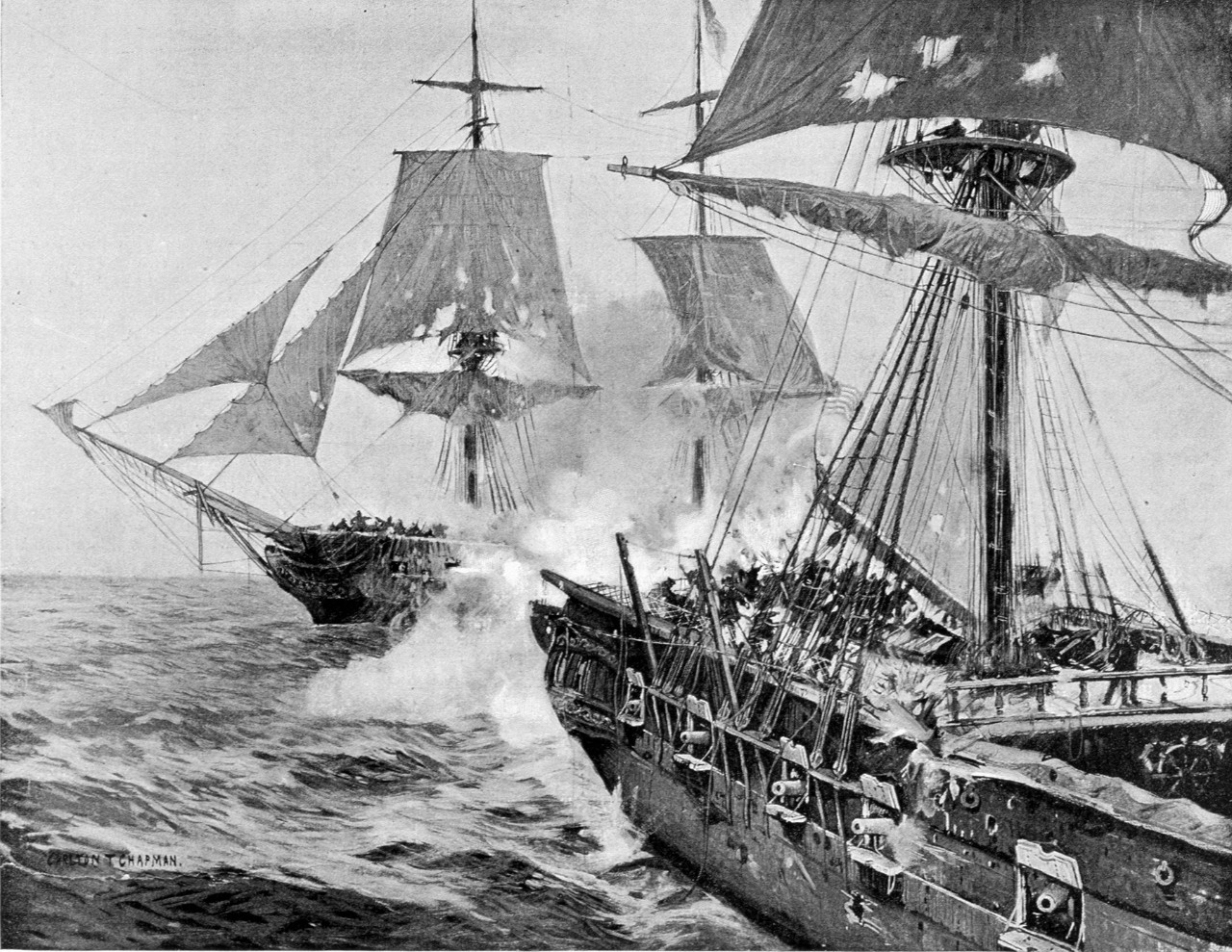

Today in Naval History—The Lesser-Known Enterprise

On Sept. 5, 1813, during the War of 1812, brig-rigged schooner Enterprise, commanded by Lt. William Burrows, sighted and chased British brig Boxer that was commanded by Capt. Samuel Blyth. After nearly six hours of maneuvering, the ships opened fire on each other and in a closely fought, fierce, and gallant 30-minute engagement that took the lives of both commanding officers, Enterprise captured Boxer. During the fight and after both skippers were lost, command of Enterprise devolved to Lt. Edward McCall. Lt. David McGrery assumed command of Boxer. McGrery would later describe his ship as a complete wreck with three feet of water in the hold. After the British ship surrendered, Enterprise set sail for nearby Portland, Maine, with the prize, the captured British crew, and casualties from the clash. Upon their arrival, newspapers in the United States reported on “another brilliant naval victory” for the reestablished Navy. Then, after two days of planning, authorities conducted a state funeral to honor the two dead commanding officers. They were respectively buried side-by-side in Portland’s Eastern Cemetery.

After making repairs, Enterprise hoisted its sails for the Caribbean in company with brig Rattlesnake. The two ships took three prizes before being forced to separate by a heavily armed enemy ship on Feb. 25, 1814. Enterprise was forced to jettison most of its guns in order to outrun the superior adversary. Enterprise reached Wilmington, North Carolina, on March 9, 1814, then spent the remainder of the war as a guard ship off Charleston, South Carolina. Enterprise served one more short tour in the Mediterranean (July–November 1815), then cruised the northeastern seaboard until November 1817. From that time, it patrolled the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, suppressing pirates, smugglers, and slave traders. During that duty, Enterprise took 13 prizes.

The lesser-known namesake ship of the famous Enterprise (CV-6) and Enterprise (CVN-65) was first put to sea on Dec. 17, 1799. It departed the Delaware Capes for the Caribbean to protect American merchant ships from French privateers during the Quasi-War with France. Within the following year, Enterprise captured eight privateers and liberated 11 American vessels from the French. Enterprise next sailed to the Mediterranean, raising Gibraltar on June 26, 1801, where it joined other U.S. warships. Its first action came on Aug. 1, 1801, when, just west of Malta, it defeated 14-gun Tripolitan corsair Tripoli after a fierce but one-sided American victory. Its next triumphs came in 1803 after an extended period of carrying dispatches, convoying merchant ships, and patrolling the Mediterranean. On Jan. 17, Enterprise captured Paulina, a Tunisian ship under charter to the Bashaw of Tripoli, and on May 22, it ran a 30-ton craft ashore on the coast of Tripoli. For the next month, Enterprise and other ships of the squadron cruised inshore, bombarding the coast and sending landing parties to destroy enemy small craft.

On Dec. 23, 1803, after a quiet interval of cruising, Enterprise joined frigate Constitution in the capture of the Tripolitan ketch Mastico. Refitted and renamed Intrepid, the vessel was assigned to Enterprise’s commanding officer, Lt. Stephen Decatur, Jr., for use in a daring expedition to burn frigate Philadelphia, which had been captured by the Tripolitans and was anchored in the harbor of Tripoli. Decatur and his crew destroyed the frigate, depriving Tripoli of a powerful warship. Enterprise continued to patrol the Barbary Coast until July 1804, when it joined the other ships of the squadron in general attacks on the city of Tripoli over a period of several weeks.

Enterprise spent the winter in Venice, Italy, where it was practically rebuilt by May 1805. It rejoined its squadron in July and resumed patrols and convoy duty until August 1807. During that period, it fought a brief engagement (Aug. 15, 1806) off Gibraltar with a group of Spanish gunboats which attacked Enterprise but were driven off by the more powerful ship. Enterprise returned to the United States in late 1807 and cruised coastal waters until June 1809. After a brief tour in the Mediterranean, it sailed to New York where it was laid up for nearly a year. It was ultimately repaired at the Washington Navy Yard before it was recommissioned there in April 1811. It then raised sail for operations out of Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina. Enterprise returned to Washington, DC, on Oct. 2 and was hauled out of the water for extensive repairs and modifications. When Enterprise was once again at sea on May 20, 1812, war was declared on Great Britain. During the first year of America’s second war with Great Britain, it cruised along the U.S. eastern seaboard. After the epic battle with Boxer and subsequent patrols in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, its long career ended on July 9, 1823, when, without injury to its crew, Enterprise was stranded and broke up on Little Curacao Island in the West Indies.