Painting of the sinking of Dutch light cruiser De Ruyter during the Battle of the Java Sea, Feb. 27, 1942. Australian light cruiser Perth is in the background followed by USS Houston (CA-30). De Ruyter was the flagship of Dutch Rear Adm. Karel Doorman, commander of the ABDACOM (American, British, Dutch, and Australian Command).

Battles of the Java Sea and Sunda Strait

On Feb. 27, 1942, the Battle of the Java Sea began when an ad hoc Allied force attempted to halt the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies colony of Java. Known as the Asiatic Fleet’s ABDACOM (American, British, Dutch, and Australian Command), it was activated on Jan. 15, 1942, to deny the Imperial Japanese Navy access to the Indian Ocean, via the so-called Malay Barrier. The force, under the command of Dutch Rear Adm. Karel Doorman, consisted of 1 heavy cruiser, 2 light cruisers, 13 destroyers, 2 minesweepers, 25 submarines, 10 auxiliaries, and 28 long-range amphibious patrol aircraft. Although the ABDACOM seemed impressive on paper, many of the U.S. surface vessels dated back to the World War I–era, and all were inadequately armed to effectively counter airborne attacks. Their voyage from Philippine waters to ports in Borneo, Java, and Australia were conducted under the constant harassment of Japanese bombers that damaged a number of ships. In addition, Japanese aircraft attacks caused wide dispersion of the ABDACOM, further impeding the command structure already handicapped by supply limitations, lack of common communication systems, and differing training and execution of operations. The Japanese surface force at Java consisted of 2 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, and 14 destroyers.

In what was the largest surface action to date since the 1916 Battle of Jutland, the Japanese Navy repeatedly outmaneuvered the Allied force, aided by cruiser scout planes. At the time, it was believed that due to advancements in gunnery fire control, surface actions would be decided in mere minutes. However, the Battle of the Java Sea turned into an hours-long late afternoon/evening gunnery duel in which the Allies and the Japanese both squandered hundreds of rounds per ship with limited results. Eventually, American cruiser USS Houston (CA-30) was hit with two dud 8-inch shells, before HMS Exeter suffered a critical hit that threw the entire Allied force into disarray. As Exeter fell out of line, Japanese destroyers closed in to attack with torpedoes. In the commotion that followed, Dutch destroyer Kortenear and British destroyer Electra were sunk. U.S. destroyers countered with their own torpedoes but came away with no hits (mostly due to malfunctioning torpedoes). As night fell, the Allied force drifted into a recently laid minefield, and British destroyer HMS Jupiter hit one, blew up, and sank. At this point in the battle, U.S. destroyers, low on fuel and with all torpedoes expended, were detached to return to Surabaya along with damaged Exeter and Dutch destroyer Witte de Witt.

The remaining combined force, without destroyer protection, continued to fight throughout the course of the night. However, the Japanese had an advantage in pyrotechnics and night optics that stymied the ABDACOM. In the end, the Japanese launched torpedo attacks that the Allied ships did not see coming under the cover of darkness. The attacks were spearheaded by the extended-range Japanese Type 93 “oxygen” torpedo, later known as the “Long Lance,” which was unknown technology to the Allies at the time. Dutch light cruisers De Ruyter and Java were both hit, exploded, and sank, with heavy loss of life. Doorman went down with his flagship, De Ruyter. Executing Doorman’s standing order to break off contact in the event of the loss of communications with his flagship, most of the force proceeded to Tanjung Priok, the port for Batavia, now Jakarta. The disastrous Battle of the Java Sea was over, and the following day, only Houston and Australian cruiser HMAS Perth remained in the vicinity.

The two ships steamed into Banten Bay on Java’s northern coast, hoping to engage the Japanese invasion force assembled there. Houston and Perth sank one transport ship and forced three others to beach. However, a Japanese destroyer squadron blocked Sunda Strait, the Allied ships’ means of retreat, and enemy cruisers approached from their seaward side. In the ensuing Battle of Sunda Strait, Perth was sunk by gunfire and torpedo hits. Houston fought alone against overwhelming odds, but it was handicapped by bomb damage inflicted previously to its number 3 turret. Soon after midnight, Houston was struck by a torpedo and began to lose headway. It scored hits on three different destroyers and sank a minesweeper but suffered three more torpedo hits in quick succession. An hour later, Houston slipped below the waves. Although it is not known exactly how many American Sailors went down with Houston, of its crew of about 1,100, hundreds initially survived the sinking. Of the Sailors who were alive in the water, about 150 perished from wounds, drowning, exposure, or Japanese machine-gun fire. A total of 291 were captured and ultimately survived the war, enduring three-and-a-half years of starvation, disease, torture, and forced labor in brutal Japanese prison camps. Overall, during the battles, the ABDACOM lost 11 ships, more than 3,370 were killed, and nearly 15,000 taken as prisoners of war. Houston’s commanding officer, Capt. Albert H. Rooks, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor “for heroism, outstanding courage, gallantry in action, and distinguished service in the line of his profession.” Cmdr. (Chaplain) George Rentz was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for selflessly giving his life jacket to a young wounded Sailor who didn’t have one. Rentz was the only Navy chaplain awarded the Navy Cross, the Navy’s second highest award for valor, during World War II. Houston was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation, the highest award that can be given to a ship.

Eight women were selected as the first female candidates to attend the U.S. Navy’s flight school (four naval officers and four civilians). The first four female Navy officers chosen for flight training (left to right): Lt. (j.g.) Barbara A. Rainey, Ensign Jane M. Skiles, Lt. (j.g.) Judith A. Neuffer, and Ensign Kathleen L. McNary.

Trailblazer Earns Wings of Gold—50 Years Ago

On Feb. 22, 1974, Lt. (j.g.) Barbara (Allen) Rainey became the first woman to earn wings of gold and be designated as a naval aviator during ceremonies at Naval Air Station Corpus Christi, Texas. She went on to serve with Pacific Fleet and flew a C-1A (TF-1) Trader based out of Alameda, California. Rainey also became the first woman in the Navy to qualify in a jet-powered aircraft, the T-39 Sabreliner. In November 1977, Rainey resigned her active duty Navy commission when she and her husband, John C. Rainey (whom she had met in high school), learned she was pregnant with their first of two daughters. While pregnant, she remained in the Naval Reserve and qualified to fly the R6D/C-118 Liftmaster. In 1981, the Navy experienced a shortage of instructors, so Rainey went back on active duty as a flight instructor with the rank of lieutenant commander. She served with Training Squadron 3 (VT-3) based at Naval Air Station Whiting Field, Florida, where she flew the T-34C Turbo Mentor.

On July 13, 1982, while practicing touch-and-go landings with her trainee, Ensign Donald B. Knowlton, their T-34C crashed at Middleton Field near Evergreen, Alabama. While in the traffic pattern, the aircraft suddenly banked to the right and lost altitude. Both Rainey and Knowlton were killed. Rainey was just 34 years old. She is buried at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, and her headstone stone is inscribed, “First Woman Naval Aviator. Loving Wife and Mother.”

Born on Aug. 20, 1948, at Bethesda Naval Hospital, Maryland, Rainey was the daughter of a career naval officer. She graduated from Lakewood High School, Lakewood, California, and was an outstanding athlete and consistently on the dean’s list at Long Beach Community College before she transferred to Whittier College, also in California. In November 1970, she was commissioned in the U.S. Naval Reserve during ceremonies at the U.S. Navy Officer Candidate School in Newport, Rhode Island, and was assigned to Naval Amphibious Base Little Creek, Virginia, later transferring to Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic in Norfolk. Seeking a greater challenge and following in the footsteps of her U.S. Marine Corps aviator brother, Bill, she applied to and was accepted into naval flight training.

In early 1973, Secretary of the Navy John Warner announced a test program to train women to be naval aviators, and on March 2, eight women (four naval officers and four civilians) were selected and reported to flight school. The following year, “The First Six” graduated and were designated naval aviators. In the 50 years since then, naval aviation has expanded its roles for women to lead and serve globally. Today, women aviators project power from the sea and in every type, model, and series of aircraft. They fly and fight in all strike missions, hunt submarines, protect the integrity of our nuclear triad, supply essential cargo and personnel to every corner of the globe, and rescue those in distress at sea and ashore. They command aircraft carriers, carrier air wings, squadrons, and missions to space. For more on women in the Navy, visit NHHC’s website.

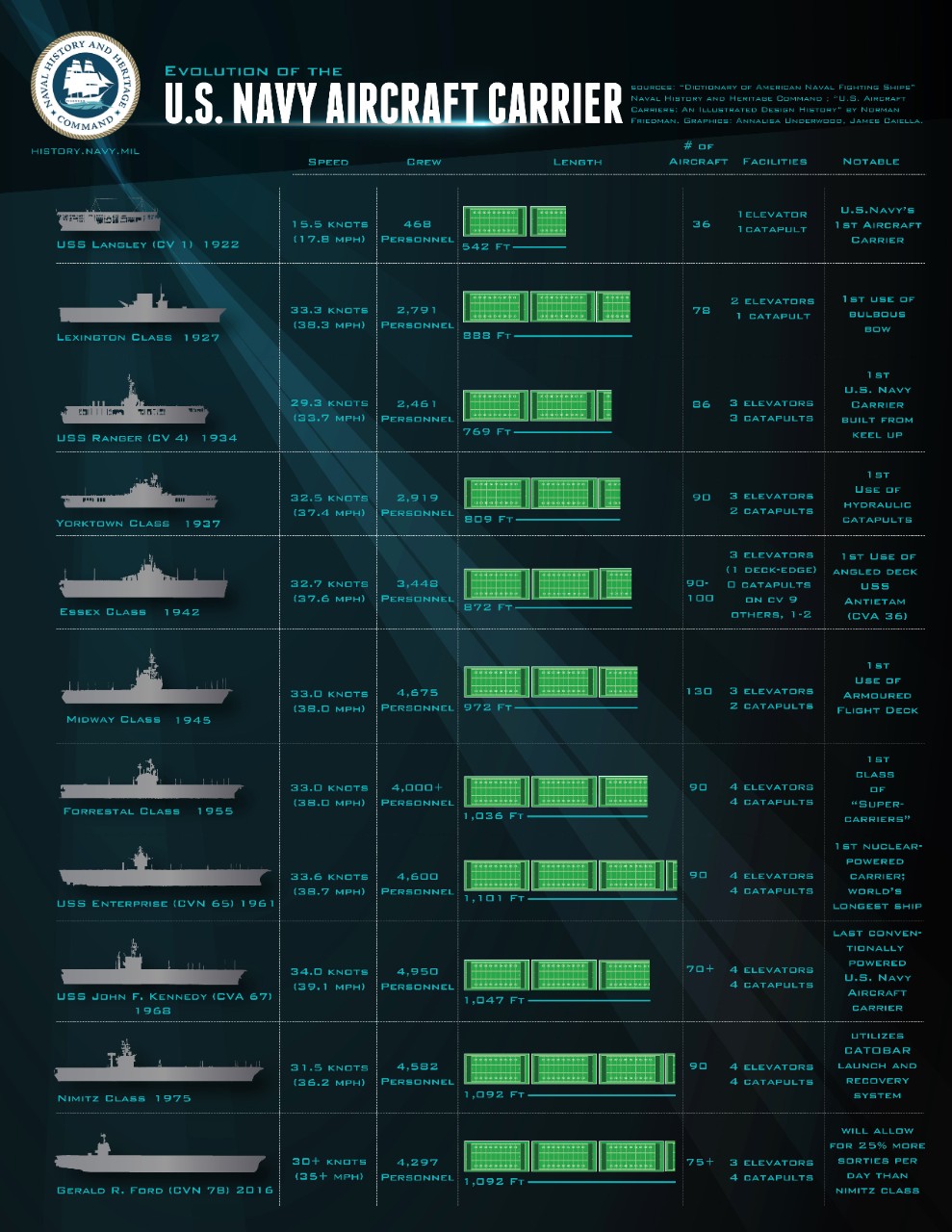

First U.S. Navy Ship Built As Aircraft Carrier

On Feb. 25, 1933, USS Ranger (CV-4), the first U.S. Navy ship designed and built from the keel up as an aircraft carrier, was launched at Newport News, Virginia. The ship was later commissioned on June 4, 1934, at the Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia, with First Lady Lou Henry Hoover as its sponsor. At the time, Ranger was the fourth aircraft carrier in the Navy’s inventory. The other three carriers were converted vessels—USS Langley (CV-1) from a collier, and USS Lexington (CV-2) and USS Saratoga (CV-3) from incomplete battle cruisers. During the planning of Ranger, an island superstructure was not included but was added after its completion. The flight deck was sheathed in wood as a weight-saving measure that was found to be easily repairable by the crew. Ranger was capable of housing more than 70 aircraft that were moved between the flight and hangar decks with its three elevators. It was one of the first U.S. Navy ships mounted with light automatic weapons to defend against dive-bombing attacks and was initially armed with 40 .50 caliber machine guns that were arrayed along the gallery. The ship was also equipped with 5-inch guns for added protection. Ranger was the first and only ship of its class.

After Ranger was commissioned, it conducted routine operations off the U.S. eastern seaboard before transiting the Panama Canal on its way to San Diego, where it made southern California its homeport for the next four years. The ship returned to Norfolk in April 1939. On Dec. 7, 1941, Ranger was conducting neutrality patrols when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. As the only carrier in the Atlantic Fleet, Ranger led the task force comprising itself and four Sangamon-class escort carriers during Operation Torch, providing air superiority during the amphibious landings on German-dominated French Morocco, Nov. 8–11, 1942. During the operation, Ranger launched 496 combat sorties. Its aircraft scored two direct hits on French destroyer leader Albatros that wrecked the ships forward half and sank the ship. In addition, Ranger’s attack aircraft pounded French light cruiser Primauguet, dropped depth charges on two submarines, and knocked out coastal defense and antiaircraft batteries. In all, Ranger’s aviation assets destroyed 70 enemy aircraft on the ground, shot down another 15 in aerial combat, immobilized 21 enemy tanks, and destroyed 86 military vehicles.

After a period of repairs and training, Ranger departed Scapa Flow, Scotland, on Oct. 2, 1943, to attack German shipping in the Norwegian port of Bodo. Before dawn on Oct. 4, the task force reached launch position off Vestfjord completely undetected. Shortly thereafter, Ranger launched 20 Dauntless dive bombers and an escort of eight Wildcat fighters. A group of the dive bombers attacked the 8,000-ton freighter La Plata, while the rest continued north to attack a German convoy, subsequently severely damaging a 10,000-ton tanker and a smaller troop transport. In addition, they sank two German merchantmen. A second attack group launched from the deck of Ranger—10 Avengers and 6 Wildcats—destroyed an enemy freighter and a small coaster and bombed a troop transport ship. During the operation, only three of Ranger’s aircraft were lost to antiaircraft fire. Later that afternoon, the Germans finally located Ranger, but of the three enemy aircraft that attacked, two were shot down and the other was chased away. Ranger returned to Scapa Flow on Oct. 6.

While in company with the British, Ranger patrolled in the waters of Iceland for about a month-and-a-half and then departed Hvalfjord for Boston, arriving on Dec. 4. One month later, Ranger was designated a training carrier operating out of Quonset Point, Rhode Island. The temporary duty was interrupted on April 20, 1944, when it arrived at Staten Island, New York, to load 76 P-38 fighter planes together with Army, Navy, and French naval personnel for transport to Casablanca. Ranger arrived at its destination on May 4, loaded aircraft destined for stateside repairs, embarked military personnel for the return to New York, and arrived on May 16.

After delivering the equipment and personnel, Ranger entered the Norfolk Navy Yard to have its flight deck strengthened and for the installation of a new type of catapult, radar, and associated gear that provided the ship with the capacity to conduct night fighter interceptor training. On July 11, Ranger departed Norfolk, transited the Panama Canal five days later, and arrived in San Diego on July 25. After unloading more than 1,000 passengers and the aircraft of Night Fighting Squadron 102, it steamed for Hawaiian waters, reaching Pearl Harbor on Aug. 3. For the next several months, Ranger conducted night carrier training operations out of Pearl Harbor. On Oct. 18, it departed for San Diego and remained there training air groups and squadrons along the California coast for the duration of the war. Ranger earned two battle stars for its World War II service.

After the war, Ranger embarked civilian and military passengers in San Diego and steamed to New Orleans for Navy Day celebrations, arriving Oct. 18, 1945. Following the celebrations, Ranger was underway for the U.S. East Coast, making several stops before it entered the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard on Nov. 18 for overhaul. The ship remained on the eastern seaboard until it was decommissioned at Norfolk on Oct. 18, 1946. For more on the history of U.S. Navy aircraft carriers, visit NHHC’s website.

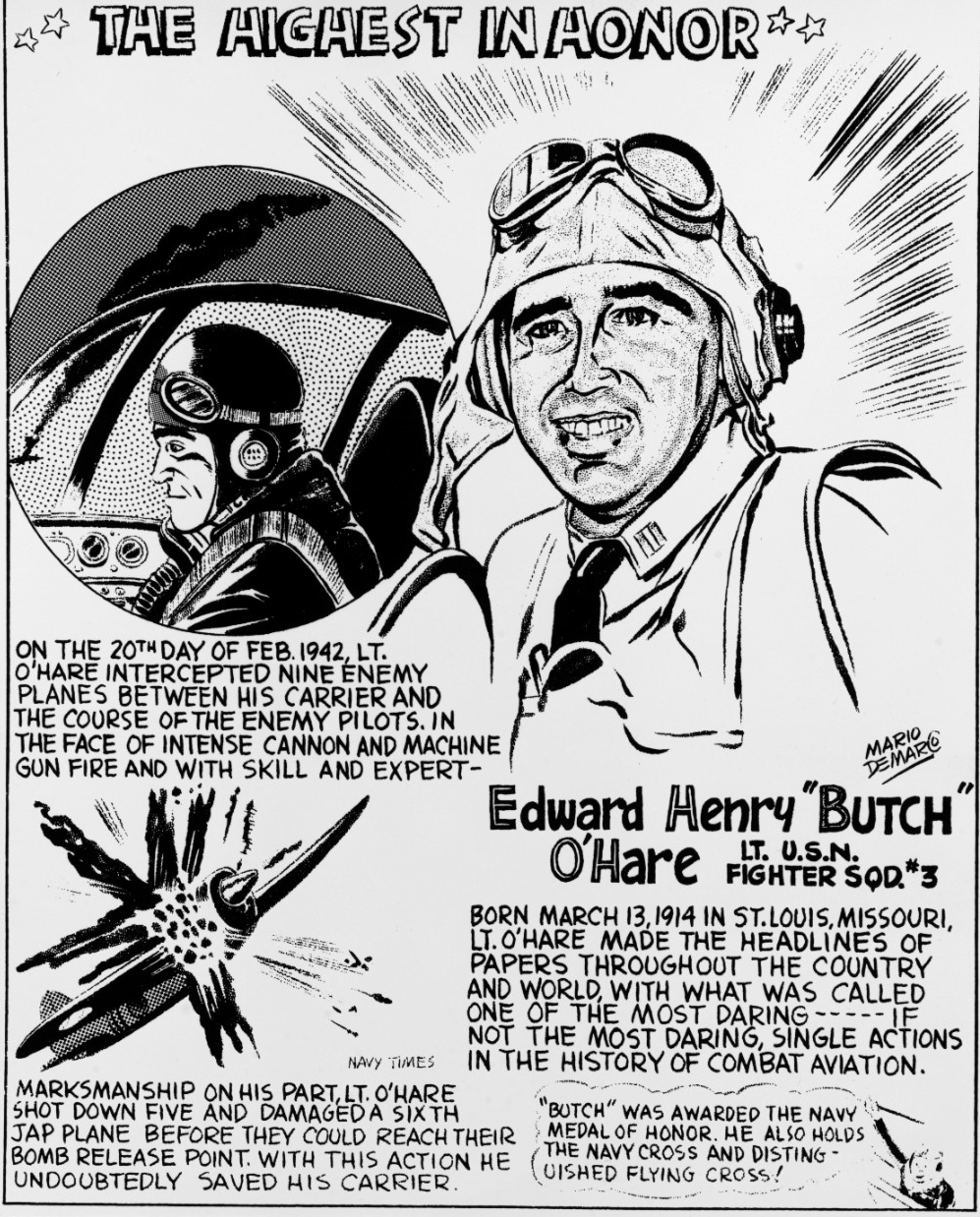

Today in Naval History—O’Hare Shoots Down Five Enemy Aircraft

On Feb. 20, 1942, Lt. Edward H. “Butch” O’Hare in his F4F Wildcat fighter single-handedly shot down five Japanese bombers and severely damaged a sixth in a single sortie while protecting USS Lexington (CV-2) about 500 miles northeast of Rabaul, New Britain. In all, Lexington’s Fighting Squadron 3 (VF-3) and the ship’s antiaircraft decimated two waves (nine aircraft each) of Japanese Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers during the engagement. For his actions on that day, O’Hare was awarded the Medal of Honor on April 21, 1942, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and promoted to lieutenant commander, by order of the President.

During the enemy attack, VF-3 maneuvered to take on the incoming bombers. Although VF-3 was composed of highly trained naval aviators, it was their first combat operation. One section of Wildcats, under the command of VF-3’s commander, Lt. Cmdr. John Thach, attacked nine of the incoming Betty bombers, shooting down three of them and driving the rest away. However, while Thach’s group was attacking one part of the Japanese force, another section of enemy bombers headed for Lexington from the opposite direction. As the bombers dived to attack the carrier, only two Wildcats were in their way—those piloted by Lt. Marion Dufilho and O’Hare. The Browning .50-caliber machine guns on Dufilho’s Wildcat jammed, leaving O’Hare as the sole plane that could interdict the oncoming Japanese force. O’Hare maneuvered his Wildcat above the Japanese bombers and dove down on the formation. As the bombers flew toward Lexington, O’Hare made a series of slashing passes, downing the enemy aircraft one by one. The bombers that did make it through O’Hare’s attacks, and Lexington’s antiaircraft fire dropped 250-kilogram bombs astern of the carrier, but no damage was inflicted on the ship.

After landing back onboard Lexington, O’Hare claimed that he had possibly shot down six of the bombers during the attack, but he was ultimately credited with five kills. No matter the score, it was clear to all that day that O’Hare’s solo attacks had broken up the Japanese formation and saved Lexington. As the first American ace of World War II, O’Hare became a household name and was just what the nation needed in the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack. Early in the war, bad news was a constant with the fall of Wake Island on Dec. 23, 1941, Hong Kong on Christmas, and Singapore on Feb. 15, 1942. President Roosevelt realized that the country needed a hero, and O’Hare fit the bill. On April 21 at 10:45 a.m., O’Hare and his wife Rita were ushered into Roosevelt’s office where he was awarded the nation’s highest honor for bravery. On the following Saturday, a parade was held in O’Hare’s hometown of St. Louis, Missouri, in his honor. Shortly before noon, O’Hare was escorted to the backseat of a long, black open Packard, where he sat between his wife and mother Selma. As the parade proceeded, it was led by a police motorcycle escort. Then came a local marching band, parading veterans, a truck packed with photographers, O’Hare’s car, and other open cars filled with dignitaries. Bringing up the rear were 350 cadets from the Western Military Academy. The next day, as O’Hare’s mother and sisters clipped newspaper stories and photos, O’Hare’s heroic feat began to dawn on them. One headline read, “60,000 give O’Hare a hero’s welcome here.” The parade was compared with those honoring the St. Louis Cardinals’ 1926 National League championship and Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 homecoming after his New York–Paris flight.

After the fanfare, O’Hare said goodbye to his wife and newborn daughter Kathleen and returned to his squadron in Maui, Hawaii. In August 1943, O’Hare was promoted to air group commander, overseeing three squadrons. On Nov. 10, his air group was assigned to USS Enterprise (CV-6), which joined a task force bound for the Gilbert Islands. The attacks on two atolls in the Gilbert Islands, Tarawa and Makin, would be the first American amphibious attacks in the Central Pacific. Beginning on Nov. 19, O’Hare’s air group supported the assault on Makin. At dusk the next day, Japanese bombers attacked USS Independence (CV-22). Hellcats rose to confront the enemy bombers, but of the five torpedoes launched at Independence, one managed to hit the carrier’s starboard quarter, seriously damaging the ship. The task-force commander, Rear Adm. Arthur W. Radford, asked O’Hare to devise a defense against a repeat dusk attack. After some thought, he created three-plane teams—two Hellcats and an Avenger torpedo bomber carrying radar. The plan was for Enterprise to launch the teams at dusk, and the officer in the carrier’s combat information center would direct them toward Japanese planes as they appeared on the ship’s radar. The Avenger pilot would then follow the center’s directions, flying toward the Japanese planes until they showed up on the plane’s radar screen as well. When the pilot could visually see the enemy planes, he would direct the two Hellcats to attack. O’Hare named the fighter teams the “Black Panthers.”

On the afternoon of Nov. 26, Enterprise’s combat information center alerted O’Hare to a group of 20 inbound Betty bombers. As night fell, O’Hare and another Hellcat were launched; however, the Avenger wasn’t initially launched when Enterprise’s fighter direction officer (FDO) suddenly changed the plan. Instead, the FDO sent O’Hare and the other Hellcat on a search for low-flying Bettys. At 7:05 p.m., the incoming Bettys attacked. The American ships protecting the carriers raised a curtain of antiaircraft fire, and the entire task force was maneuvered to deny the bombers appropriate torpedo-attack angles. To the east, O’Hare and his wingman fired at several fleeting Bettys but hit nothing. The FDO directed the Hellcats toward the now airborne Avenger. Shortly afterward, the Avenger’s rear-facing gunner saw the two Hellcats slide in behind the Avenger from above. At almost the same instant, a fourth plane appeared from above and behind O’Hare. The Japanese plane fired first, with its nose down into O’Hare’s Hellcat. Shortly thereafter, the Avenger’s crew witnessed something splashing into the sea. During the engagement, several Japanese planes were shot down, but only one American plane was lost. It was O’Hare. In the aftermath, there was an extensive search, but O’Hare’s body was never recovered.

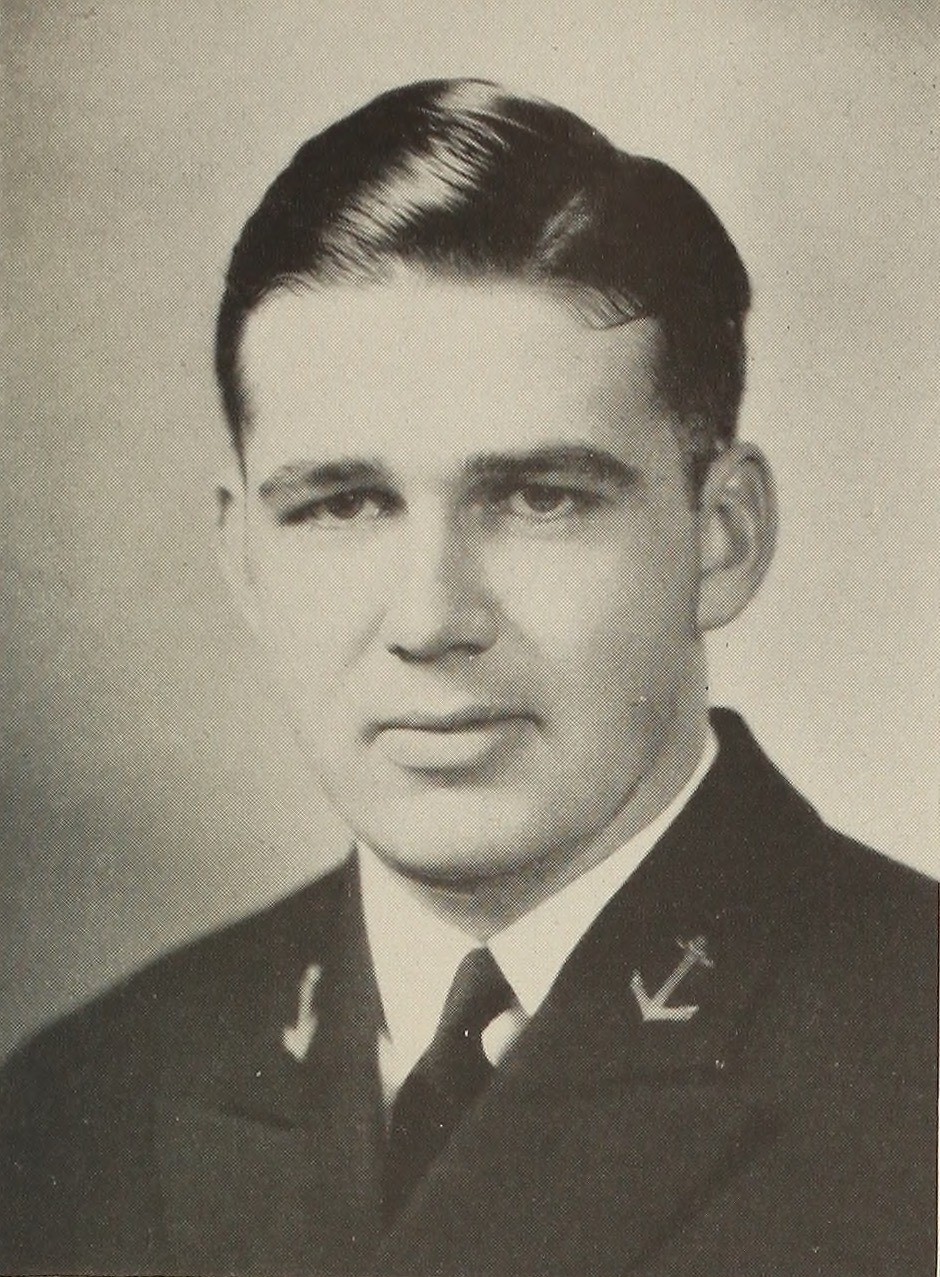

O’Hare was born on March 13, 1914, in St. Louis. While growing up, his father, Edgar, was determined to instill some discipline into his son, enrolling him at the Western Military Academy in 1927. While O’Hare proved to be just an average athlete at the academy, he demonstrated excellent marksmanship skills on the rifle team. Still determined that his son avoid his often-shady law practice, Edgar urged his young son to apply to the U.S. Naval Academy. Initially, O’Hare failed the entrance exam, but after attending a prep school, he was accepted and graduated in 1937. Nicknamed “Butch” by his classmates at the academy, O’Hare served on battleships before being accepted into the Navy’s flight program in 1939. Earning his Navy wings of gold in 1940, O’Hare was assigned to Lexington’s VF-3 as a naval aviator. Today, O’Hare is best known for his namesake, Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport, one of the busiest airports in the world. In addition, destroyer USS O’Hare (DD-889) was named in his honor.

Although Chicago was never O’Hare’s home (as his namesake airport would suggest), his father was a very influential figure in the “Windy City.” After he passed the Missouri bar exam in 1923, “EJ” or “Easy Eddie,” as he was known, was an entrepreneur new in Chicago—as was gangster Al Capone. During prohibition, Capone ran underground bootlegging and other criminal activities (drug trafficking, robbery, prostitution, murder, etc.) in the greater Chicago area. Between 1925 and 1931, EJ aligned himself with Capone, and they operated highly profitable dog tracks in Chicago, Boston, and Miami. EJ also represented Capone on all legal matters. However, over time, EJ grew tired of working with thugs. Capone and EJ argued repeatedly about the dog tracks and other matters, but Valentine’s Day 1929 may have been the final straw, with the brutal executions of several rival gang members in a Chicago whiskey warehouse. Capone’s alibi was airtight as he was in Miami at the time “suffering from bronchial pneumonia.” In 1930, EJ, who had maintained his St. Louis contacts, asked a reporter from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, to arrange a meeting with the IRS. After lunch together, EJ agreed to turn over key financial records of Capone’s seedy business dealings, and afterwards, IRS agents worked diligently with Eliot Ness at the Justice Department. The overall goal was to wreck Capone financially by destroying his moneymaking bootlegging business. After an extensive investigation and trial, Capone was convicted of tax invasion. The records, provided by EJ, helped convict Capone. After his conviction in October 1931, Capone was first sent to the U.S. penitentiary in Atlanta, then once his appeal was denied, to the federal prison on Alcatraz Island to serve out his sentence. He was released in November 1939. A week before Capone’s release, EJ was driving his new Lincoln Zephyr home from the dog track when he was gunned down by one of two men in a car that sped past him. In the aftermath of his father’s death, O’Hare took emergency leave for his father’s funeral, then reported back to flight training. Although O’Hare International Airport is named for his heroic World War II son, it was EJ that was, in part, instrumental in ridding Chicago of the Al Capone crime wave. Capone never returned to Chicago after he was released from Alcatraz.