Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Operation Flintlock—80 Years Ago

On Jan. 31, 1944, the assault on the Marshalls Islands—code-named Operation Flintlock—began with a naval bombardment and the subsequent landings of thousands of U.S. Marines and Army troops at Kwajalein Atoll and the Roi-Namur Islands. The overall commander of the operation was Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. The operation was executed by Fifth Fleet’s Vice Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, who was embarked on heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis (CA-35). Rear Adm. Richmond K. Turner commanded the joint expeditionary force, Task Force 51 (TF-51), embarked on USS Rocky Mount (AGC-3) with Marine Major Gen. Holland M. Smith, commander of expeditionary troops. Maj. Gen. Charles H. Corlett led elements of the Army’s 7th Infantry Division for the operation.

On the first day of the assault, the northern attack force landed elements of the 4th Marine Division on Roi-Namur, with the initial landings intended to capture the two small islands to secure the passes into the nearby lagoon. Based on intelligence, Rear Adm. Turner was worried that Roi-Namur would be a tougher fight than Betio was at Tarawa (a lot was learned from the bloody Operation Galvanic months earlier). However, the Japanese were not expecting the landings to come from inside the lagoon and had arrayed their defenses to defend against an assault from the seaward side. Days of air and battleship bombardment had destroyed all 83 of the Japanese aircraft on the islands as well as many of the Japanese fortifications. Battleships had pounded the islands with some 6,000 tons of munitions. Although the seizure of the small islands flanking the entrances to the lagoon was hampered by heavy seas, the initial objectives were accomplished by the end of the first day. Subsequent U.S. artillery emplaced on the islands along with gunboats continued firing on Japanese positions throughout the night. Early the following day, three U.S. destroyers used rapid fire to cover a reconnaissance mission from USS Schley (APD-14). The reconnaissance confirmed that the lagoon-side beaches were cleared for landings. Battleship bombardments continued, but they were lifted long enough for a daybreak reconnaissance by underwater demolition teams for a last- minute check and clearance of beach obstacles. At about noon, the first wave of Marines hit the beaches, assisted by close-in gunfire support from USS Johnston (DD-557). During the initial landings, at 12:45 p.m., a massive Japanese ammunition dump on Namur exploded, killing 20 Marines. Although tough fighting continued throughout the day and into the next, Roi-Namur was declared secure on the afternoon of Feb. 2.

The southern attack force began its attack on the island of Kwajalein and nearby islands on Jan. 30 when battleship USS Washington (BB-56) bombarded one of the islands flanking a key passage into the lagoon. Other warships battered the islands the next day. Although the passes were assumed to be heavily defended, the Japanese did not anticipate that the assault would once again come from the lagoon side, nor did they anticipate that the Navy’s tracked landing vehicles would be able to cross the reefs. The flanking islets did not have artillery, nor were the passes mined or obstructed. In addition, Kwajalein was so narrow that there was no opportunity for the Japanese to form a defense. The initial U.S. Army landings went reasonably well, although in one instance troops were landed on the wrong island. Nevertheless, the Soldiers that landed on the wrong island went aboard a beached Japanese vessel and found a treasure trove of 75 secret charts of lagoons and harbors across the Pacific, which proved extremely valuable during future operations. By Feb. 1, the appropriate islets had been secured.

Heavy battleship bombardment of Kwajalein continued for the next several days. As the bombardment commenced, American destroyers entered the lagoon, covering the arrival of amphibious ships and craft. The subsequent amphibious assault and supporting fires worked so well that within 12 minutes 1,200 7th Infantry Division Soldiers were ashore without a single casualty. However, resistance began to stiffen considerably. Tough fighting continued on Kwajalein until Feb. 6.

By Feb. 7, landings had been completed on 30 different islets around Kwajalein without one U.S. ship being sunk. The entire operation cost the lives of 372 Soldiers and Marines. Of the more than 3,500 Japanese defenders on Kwajalein, only 174 were taken as prisoners of war. The relatively easy capture of Kwajalein demonstrated the superior amphibious capabilities of the U.S. Navy and showed that changes in training and tactics after the costly Battle of Tarawa were effective.

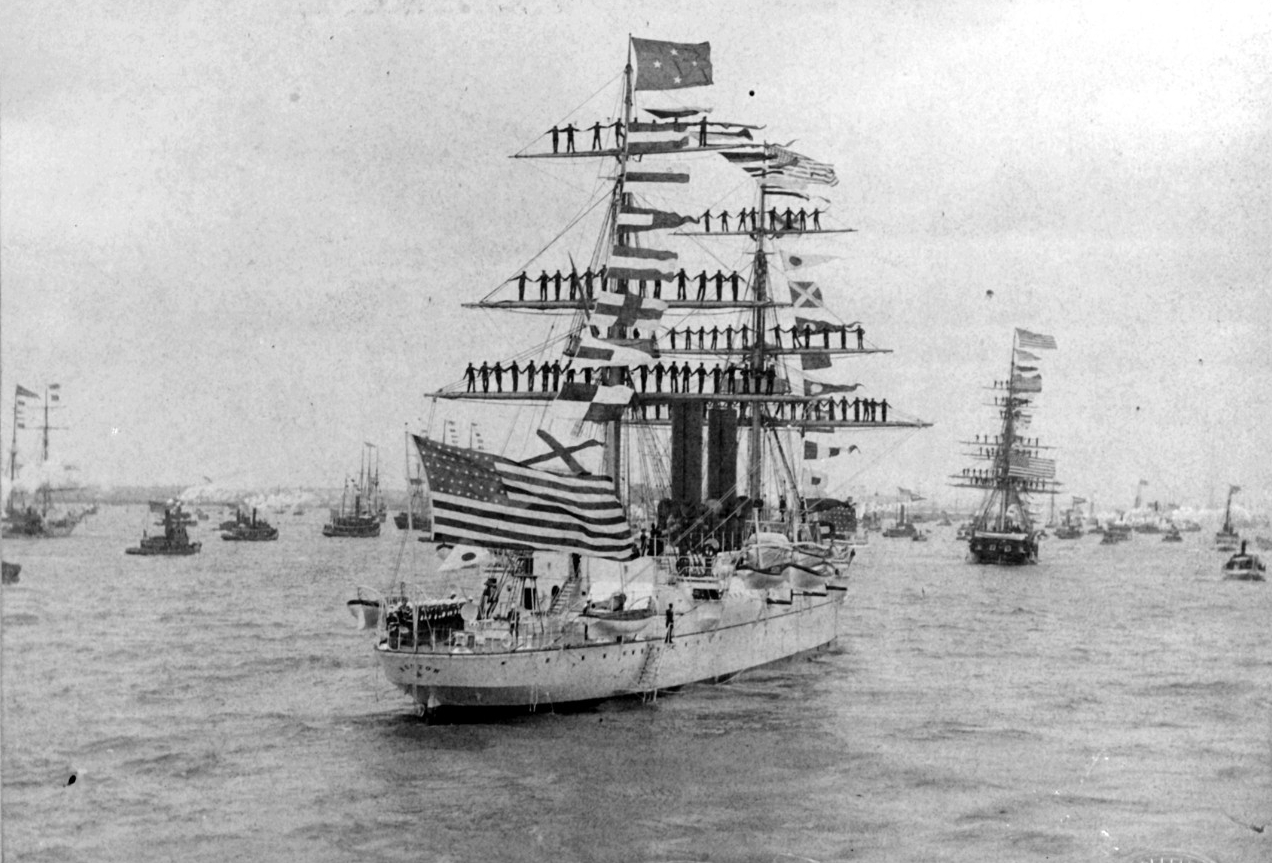

Protected cruiser Boston dressed with flags and manning its yards during the Centennial Naval Parade in New York Harbor, April 29, 1889 (centennial of George Washington's first inauguration). Boston was the third protected cruiser commissioned of the first four ABCD ships in the transition from wood and sail to steel and steam.

The Steel Navy—The Transition from Wood and Sail to Steel and Steam

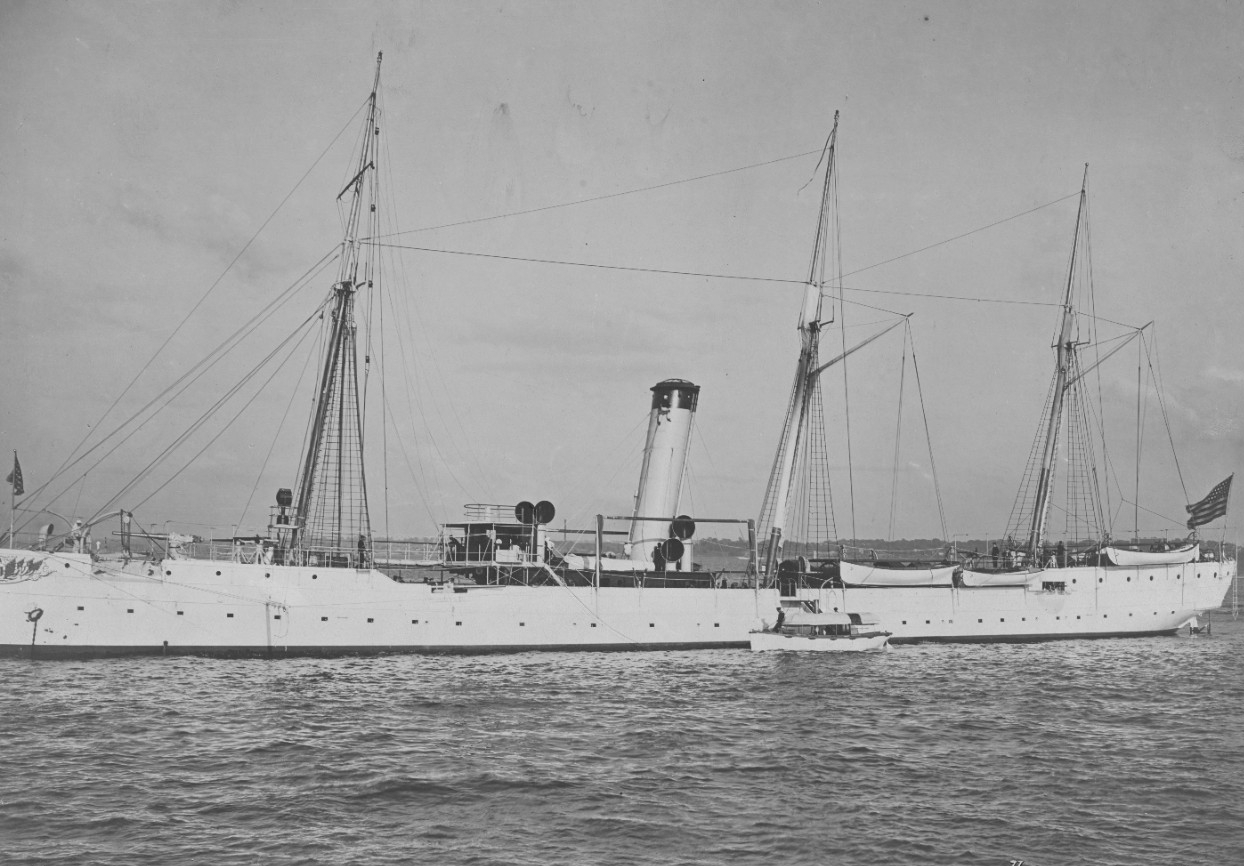

Recently, Naval History and Heritage Command published a new webpage that details the U.S. Navy’s transition from wood and sail to steel and steam ships. The modernization, funded through the “New Navy” initiative, announced to the rest of the world that the United States was intent on once again becoming a modern naval power. On March 3, 1883, after nearly two decades of neglect following the Civil War, the United States began a period of naval modernization when Congress authorized the construction of the country’s first steel-hulled, steam-propelled warships. Known as the “ABCD” ships, Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, and Dolphin (PG-24) were the first built (converted in Dolphin’s case) during the Navy’s transition. The new ships were hybrids of old and new technology that featured hulls constructed of steel with relatively powerful steam engines but were also capable of operating under sail. The first of the ships, Dolphin, commissioned on Dec. 8, 1885, was originally built to be a dispatch vessel, but after it was successfully converted, Dolphin was a stepping stone in the construction of the three larger steel-hulled, steam-powered protected cruisers (Atlanta, Boston, and Chicago). Although the ABCD ships were already deemed obsolete by the time they were commissioned, they paved the way for more modern warships with the construction of second-class battleships such as Maine (commissioned in 1895) that were experimental, yet considered state-of-the-art at the time.

Prior to the commissioning of the ABCD ships, the Navy was in a state of decline, still exhausted by the Civil War and neglected by a country preoccupied with reconstruction and westward expansion. At the time, other countries were experimenting with iron and steel ship hulls and improved steam-propulsion technology. By the 1880s, the U.S. Navy was outclassed by numerous navies from around the world and seemingly content with the undemanding mission of showing the flag in foreign ports with its Civil War fleet of gunboats and ironclads. In 1882, the Navy’s inventory consisted of just 14 ironclads (mostly Civil War–era monitors) and a few wooden sailing vessels. The most powerfully armed vessels in the depleted American fleet were armed with nothing more powerful than five-inch smoothbore guns. The lack of modernization was partly a byproduct of an ongoing debate about what the Navy’s postwar role should be and what types of ships, if any, should be built. Many Americans who had lived through the Civil War wanted nothing more to do with military conflicts, and some felt that strong fortifications would be enough to protect America’s coasts without getting entangled in foreign conflicts.

Beginning in 1881, Secretary of the Navy William H. Hunt assembled a naval advisory board to try to address the state of the Navy. The 15 members of the board felt that the Navy should begin a new construction program, but they disagreed over whether the new ships should be sail- or steam-driven, what kind of armament they should carry, and whether their hulls should be made of iron or steel. Though it never reached a full consensus, the board recommended that Congress set aside $30 million for the construction of 21 new vessels. The House Naval Affairs Committee subsequently rejected the proposal as too costly. Another recommendation was to buy a few steel-hulled ships from Britain, like many other countries were doing at the time. However, national pride and self-reliance led to that proposal being rejected. Also rejected was the idea of purchasing ship plans from another country that an American shipyard would build. In any event, the Sept. 19, 1881, assassination of President James Garfield put all initiatives on hold, and incoming President Chester A. Arthur replaced Hunt with his own pick for Secretary of the Navy, William E. Chandler. Chandler was also a proponent of modernization, and he successfully lobbied Congress to move forward with a drastically scaled-back construction program. On Aug. 5, 1882, Congress authorized the construction of two steel warships without appropriating any funds for them, insisting that funding would come from somewhere else within the existing budget. Although the two ships were never built, the lukewarm response put in motion the appropriations bill that would pass months later for the ABCD ships. For more, check out The Steel Navy page on NHHC’s website. It includes a short history, imagery, and the fate of the ABCD ships.

Vietnam’s Tet Offensive

In the early hours of Jan. 30–31, 1968, during Vietnam’s Lunar New Year celebrations (Tet), the Tet Offensive began when about 85,000 North Vietnamese government troops and Viet Cong guerillas simultaneously attacked major cities, military installations, and scores of towns and villages throughout South Vietnam—an estimated more than 150 South Vietnamese targets in total. It was arguably the turning point of the Vietnam War, at least in terms of public sentiment. The massive assault was an attempt to incite unrest among the South Vietnamese populace and break the war’s prolonged stalemate. The enemy-led offensive ultimately was a crushing tactical defeat for the North Vietnamese, and especially for the Viet Cong, with 45,000–58,000 enemy killed in action (including losses during the “mini-Tets” that occurred over the next eight months). To add to the defeat, the North Vietnamese abandoned the guerilla warfare approach, which was highly successful to that point and had caused American commanders consistent frustrations. Nevertheless, the media heavily publicized the offensive and its effects, dealing a psychological blow to American public and political support for the war. Ultimately, it soured the will of the United States to sustain the war.

In the months preceding the Tet Offensive, the North Vietnamese army (NVA) engaged in extensive intelligence deception operations that were designed to focus attention to the border areas of the country and away from coastal cities. In retrospect, NVA operations at Con Tien and Dak To in the central highlands made little military sense and cost the NVA heavily, but they succeeded in the deception objective. Although U.S. commanders viewed the attacks on the Khe Sanh combat base as an attempt by North Vietnam to replicate its unprecedented victory against the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, the NVA’s real objective was to bog down American and South Vietnamese forces, diverting attention away from preparations for the Tet Offensive. The North Vietnamese government also announced that it would honor a truce between Jan. 27 and Feb. 3 in conjunction with Tet, something that they actually had no intention of upholding. Allied forces accepted the stand-down, and a large number of military troops (mostly South Vietnamese) were on leave when the offensive commenced. Although several premature Viet Cong attacks occurred on Jan. 29, the day before Tet began, allied forces were unable to recall troops in a timely matter and were ill prepared.

Although the North Vietnamese had the element of surprise and there were few South Vietnamese troops initially available, the enemy attacks were beaten back in just a matter of days, with the exception of the old Vietnamese imperial capital of Hue, where two NVA battalions succeeded in occupying the citadel. It wasn’t until Feb. 25, when the South Vietnamese army and U.S. Marines recaptured Hue at the cost of 216 U.S. Marines killed and 1,600 wounded.

As part of the Tet Offensive, Viet Cong forces attacked most of the cities along the Mekong Delta, a strategically vital river of South Vietnam. The Navy’s riverine forces played a critical role in the rapid deployment of troops to repulse the enemy from every city they attempted to occupy. In several cases, naval special warfare forces from five SEAL (Sea, Air, Land) detachments transported by Navy riverine craft, drove off the Viet Cong. In addition, the North Vietnamese attempted to pour supplies into South Vietnam via trawlers and other smaller, inconspicuous-looking vessels. U.S. Navy ships operating as part of Operation Sea Dragon (the bombardment of the North Vietnam coast) interdicted some of the traffic. Most of the seaborne traffic was halted by Task Force 115 (TF-115), the coastal surveillance force executing Operation Market Time. Market Time was mostly a U.S. Navy operation with significant U.S. Coast Guard participation using patrol aircraft and smaller vessels, such as PCF “Swift” boats, to track vessels as they went far into the South China Sea before making a run for the South Vietnamese coast to drop off supplies for the Viet Cong. As much as 90 percent of Communist seaborne resupply and infiltration was estimated to have been interdicted as a result of Market Time. U.S. Navy destroyers also conducted naval gunfire support to U.S. Marine and Army operations along the coastline during the Tet Offensive.

In the end, most of the enemy forces were quickly repelled, except for the Battle of Hue and the siege of Khe Sanh. The North Vietnamese and Viet Cong paid dearly for their deviation from a guerilla warfare strategy. The Tet Offensive also resulted in more rejection among some South Vietnamese for the North Vietnam cause.

Today in Naval History—Bathyscaphe Trieste Descends to Challenger Deep

On Jan. 23, 1960, the bathyscaphe Trieste made history when Lt. Don Walsh and Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard descended seven miles to the deepest known point of the Earth’s oceans. Challenger Deep, in the northern Pacific Ocean within the Mariana Trench, is a valley between two tectonic plates that is greater in depth than the height of Mount Everest. During their nine hours submerged, Walsh and Piccard observed marine life from inside a spherical gondola and spent time exploring the ocean floor with the help of a searchlight. During the expedition, the enormous pressure at the depth of 32,400 feet caused a glass pane in an observation port to crack. The unexpected setback shortened Trieste’s stay at the bottom to just 20 minutes. Wasting no time, the crew watched flatfish and shrimp swim above the sea floor, tested the area for radiation, and called the surface ships to report that, for the first time, humankind had reached Challenger Deep.

Following the historic dive, the bathyscaphe was overhauled and then conducted a number of dives out of the San Diego area supporting Navy research objectives. In April 1963, nuclear submarine USS Thresher (SSN-593) was lost with all hands off the Massachusetts coast. Trieste was subsequently transported across the country to Boston, where it began to search for the lost submarine. After a number of dives, Trieste discovered debris from Thresher 220 miles off Cape Cod that included the submarine’s sail, which clearly showed the boat’s hull number “593.” For its part in the Thresher search, the bathyscaphe’s crew received the Navy Unit Commendation.

Trieste was the development of a concept first studied in 1937 by Swiss physicist and balloonist Auguste Piccard—Jacques’s father. World War II delayed his work on the deep-sea research submarine until 1945, when he worked with the French government on the development of the craft. In 1952, Piccard was invited to Trieste, Italy, to commence construction. Scientific and navigational instruments for the vessel came from Switzerland, Germany, and Italy. In August 1953, the bathyscaphe was first placed in the water, and later that month, Piccard and his son dove to a depth of five fathoms (30 feet). After several years of operations in the Mediterranean, the U.S. Navy acquired the vessel in August 1958 and transported it to San Diego, where it was homeported. Beginning in December of 1958, Trieste was fitted with a stronger sphere, fabricated by the Krupp steelworks of Germany. After the Thresher search mission was complete, Trieste was taken out of service and returned to San Diego. In early 1980, the bathyscaphe was transported to the Washington Navy Yard, where the vessel was on exhibit at the National Museum of the U.S. Navy.

It would be more than 50 years before another attempt would be made to reach Challenger Deep. In 2012, filmmaker James Cameron made a solo descent in Deepsea Challenger, reaching 35,787 feet. In 2019, retired naval officer Victor Vescovo made several descents in Limiting Factor to 35,843 feet, which set the world’s record for deepest dive, 52 feet deeper than Trieste.