Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

One of the Great Successes of the American Effort—Operation Market Time

On March 11, 1965, during the Vietnam War, the U.S. Navy established Operation Market Time patrols to prevent North Vietnamese ships from supplying enemy forces in South Vietnam by sea. The Coastal Surveillance Force (Task Force 115) used a system of three barriers to patrol the South Vietnamese coast. Patrol aircraft covered the outermost barrier to identify, photograph, and report suspicious vessels, and U.S. Coast Guard cutters stopped and searched cargo vessels in the middle barrier 40 miles off the coast. The South Vietnamese navy and Junk Force, and U.S. Navy patrol craft cruised the coastal waters of the inner barrier. By 1968, these forces stopped virtually all seaborne infiltration from North Vietnam to South Vietnam. The blockade forced the North Vietnamese to rely on the Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Cambodian port of Sihanoukville to transport supplies to the Viet Cong.

When the 1954 Geneva Accords divided Vietnam into south and north, it provided an opportunity that gave Communist leader Ho Chi Minh's supporters an edge—a period of free movement between the parts of the divided country. Along with thousands of his supporters left in the South, Ho Chi Minh recruited thousands more to bring to the North and train for later operations. As a result, the Communist-led National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) had a ready army in the heavily infiltrated provinces along the Mekong Delta. Since the South Vietnamese army and navy were outnumbered, they rarely patrolled the rivers and coastline to stop the movement of supplies to the guerrillas. When the United States entered the conflict, the U.S. Navy initially patrolled mostly in the deeper waters, with helicopters and patrol planes providing surveillance for American and Vietnamese ground troops. Market Time changed this equation.

Operation Market Time was named as a reference to commercial and marketing ships that would ultimately fall under South Vietnamese and American jurisdiction. All vessels were suspected of transporting contraband to enemy forces. When the Navy crews weren't stopping, boarding, and inspecting ships that ranged from trawlers to fishing boats, they provided naval gunfire support for ground forces ashore, transported troops, evacuated civilians, and provided medical outreach to the local communities. The squadrons used a variety of boats and ships, from destroyers and minesweepers that patrolled in deeper water to shallow-draft vessels such as fast patrol craft (“swift boats”), Coast Guard cutters, gunboats, and later even air-cushioned patrol vehicles. Additional backup came from observation aircraft such as P-2 Neptunes and P-3 Orions. The area of responsibility stretched across approximately 1,200 miles of coastline from Da Nang in the north to Phu Quoc Island in the south, and 40 miles out to international waters.

The success of Market Time forced the North Vietnamese to find other ways of supplying the Viet Cong. After the Tet Offensive in January 1968, when the Viet Cong executed a series of attacks throughout South Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh was desperate to replenish his troops in the South, and so he looked again toward the fastest route of delivering supplies. During the evening of Feb. 29, 1968, four separate attempts were made by Communist ships to slip through the blockades. The confrontation began south of Da Nang when a 100-foot-long trawler ignored warning shots by Coast Guard cutter Androscoggin. The trawler returned fire and the battle began, with the cutter joined by two other cutters and helicopter gunships. Trapped, the trawler’s captain headed for shore, beaching the ship. At 2:35 a.m., the trawler exploded. A second battle was fought at nearly the same time, off the Ca Mau Peninsula, when another enemy trawler tried to breach the inner barrier. Four cutters came to attack, supported by Navy swift boats. Overwhelmed by U.S. gunfire, the trawler burst into flames and exploded. Northeast of Nha Trang, another trawler was caught in the inner barrier by a force of swift boats, Vietnamese junks, Vietnamese navy vessels, fleet command ships, and an AC-47 aircraft. The trawler’s captain ran the ship onto the beach, destroying it. The captain of a fourth trawler decided to cut his losses and returned to North Vietnamese waters after Coast Guard cutter Minnetonka intercepted it in international waters near the border. After the night of engagements and failed missions, no trawler infiltration attempts were detected for the next year and a half.

By the spring of 1968, the U.S. Navy decided that Market Time had achieved a high degree of effectiveness in preventing trawler infiltrations, and by May with the arrival of Capt. Roy Hoffmann (Commander, Coastal Surveillance Force) and Vice Adm. Elmo Zumwalt (Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Vietnam and Chief, Naval Advisory Group Vietnam), TF 115 became more aggressive. Hoffmann felt that TF 115 should go on the offensive more often. A policy was instituted to use offshore patrol ships during daylight hours for offensive coastal operations and to return them to station for surveillance before dark or when visibility was reduced. The gunships, previously limited to surveillance, were given expanded rules of engagement. Enforcement of restricted zones was also emphasized, which covered high Viet Cong threat areas off the coast. Some of the zones merely had curfews, while others were restricted to commercial traffic 24 hours a day. The concept of taking the offensive was expanded in October 1968 with a renewed strategy for the Southeast Asia lakes, oceans, rivers, and the Mekong Delta. The original objectives of the operation were to interdict Viet Cong infiltration routes from Cambodia along canals from the Bassac River to the Gulf of Thailand; pacify selected Delta waterways; pacify and clear the Bassac River Islands; and harass the enemy.

By the end of 1970, there were only 14 trawler infiltration attempts. One trawler may have successfully infiltrated into the Xuyen Province in August 1970, and another was sunk on Nov. 22, 1970, while attempting to land in the Ken Hoa Province. All other trawlers aborted their missions. Vietnamization of Market Time continued throughout 1970, marking the end of the U.S. Coast Guard’s participation in Market Time. On Sept. 1, the South Vietnamese navy assumed command of the inner barrier. However, problems initially arose due to inexperience, a lack of standard operating procedures, and improperly used challenge and reply codes. U.S. Seventh Fleet continued to patrol the outer barrier offshore.

After a trawler was sunk on April 24, 1972, in international waters in the Gulf of Thailand, no other trawler infiltration attempts were detected by Market Time forces. By Aug. 15, land radar sites and one radar ship were operating under South Vietnam’s control. U.S. surface participation in coastal surveillance was officially ended with the discontinuation of TF 115 in December.

In retrospect, life aboard a Market Time vessel consisted primarily of two extremes: hours of boredom under an intensely hot tropical sun or brief periods of tension and life-threatening danger. Duty during Market Time operations, however, were not without certain benefits. For instance, commanders of Market Time ships had one luxury that was the envy of their higher-ranking counterparts on the more powerful warships of Seventh Fleet: Due to direct-link communications difficulties, micromanaging from Washington was near impossible. It was one of the few times in the war where command authority truly rested with the individual on-scene commander. The impact of Market Time in overall operations was one of the great successes of the American effort during the Vietnam War.

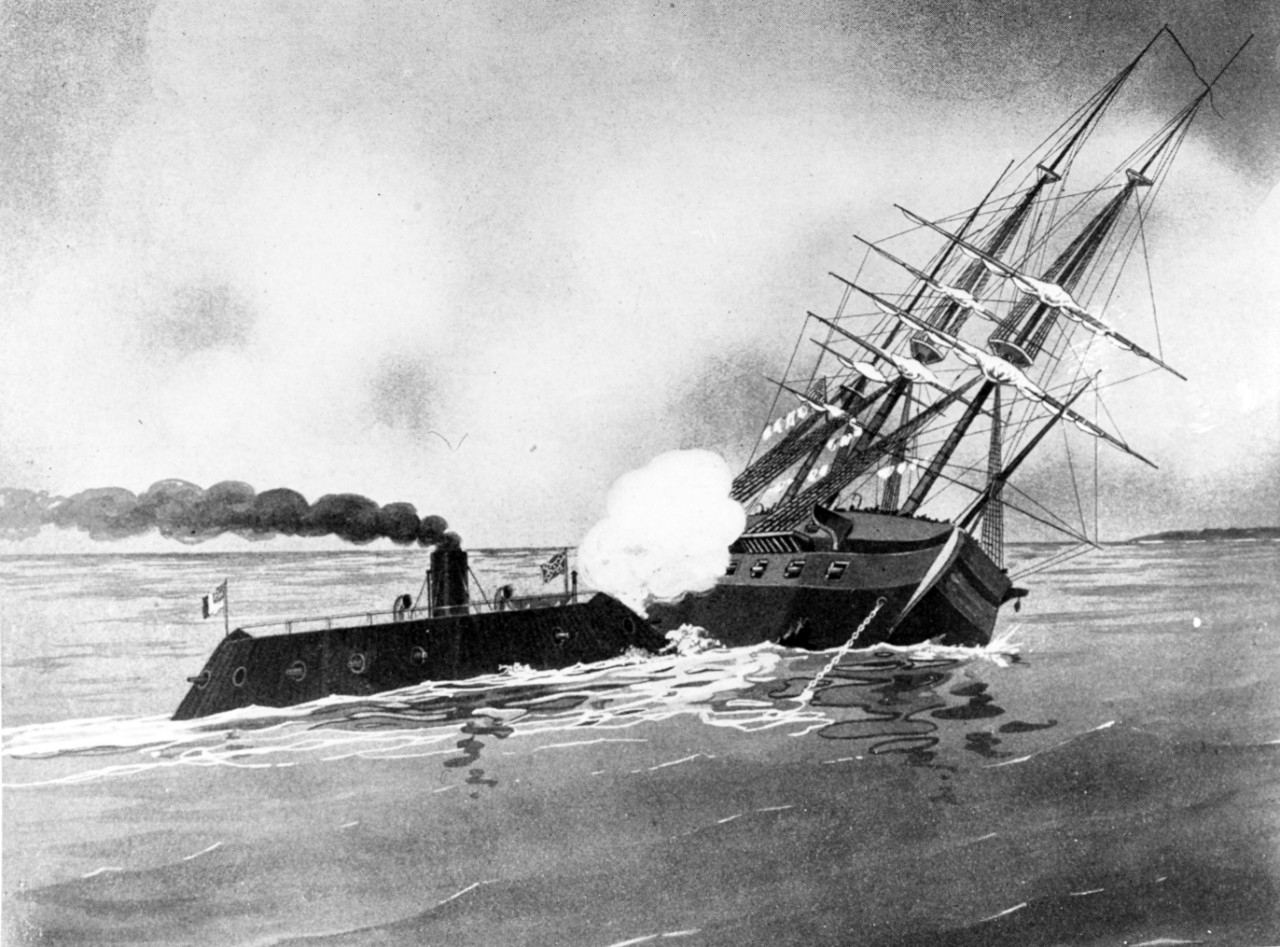

Battle of Hampton Roads—The First Ironclad Battle

In March 1862, during the Civil War, the Battle of Hampton Roads took place at the mouth of the James River in Virginia and featured the first battle between ironclad ships. The U.S. Navy–built Merrimack, a steam frigate that had been salvaged from Norfolk Navy Yard, Virginia, was rebuilt by the Confederates as an ironclad ram. Commissioned on Feb. 17, 1862, and renamed CSS Virginia, its upper hull was cut away and replaced with iron plating. Commanded by Capt. Franklin Buchanan, Virginia was a 263-foot masterpiece of improvisation that was equipped with salvaged 9-inch Dahlgren guns and muzzle-loading Brooke rifled cannon. The ship was also equipped with exterior iron shutters to protect its four gun ports after each broadside, but they were not completely installed by the time the ship departed the yard. Despite an all-out effort to complete the ship, workers were still onboard Virginia when it steamed into Hampton Roads. Regardless of Virginia’s unfinished state, the ironclad was the Confederates’ hope of breaking the Union blockade. On March 8, Virginia lived up to Confederate expectations by destroying the Union blockade ship Cumberland and the 50-gun frigate Congress, while running frigate Minnesota aground. However, Virginia did not emerge from the first day of battle completely unscathed. Buchanan was wounded and taken ashore to the hospital. Executive officer Cmdr. Catesby ap R. Jones assumed command of the ship. Its stack was riddled by shot, causing loss of power, and it was initially underpowered. Two of its large guns were out of order, its armor had loosened, and its ram had been lost.

Union ironclad USS Monitor, commanded by Lt. John L. Worden, arrived in the blockaded harbor later that night. Designed by Swedish engineer and inventor John Ericsson, the 172-foot Monitor was equipped with a water-level deck and a revolving armored gun turret with armor that was eight inches thick. Instead of the large numbers of smaller-caliber guns that characterized warships during that time, Monitor was equipped with two large 11-inch Dahlgren guns, representing an entirely new concept in naval design. Thus, the stage was set for the historic first ironclad battle.

Soon after 8 a.m., Virginia and other Confederate vessels emerged to finish the destruction it had reaped on the wooden-hulled Union ships the previous day. As it was steaming toward Minnesota (still aground), Virginia’s ironclad adversary Monitor suddenly appeared from behind the stranded vessel. Monitor proceeded to open fire, compelling all of the wooden-hulled Confederate vessels to retreat except for ironclad Virginia. For the next four hours, the two ships circled each other without inflicting much damage. Both crews lacked training and firing was ineffective. Monitor could fire only once in seven- or eight-minute spans but was faster and more maneuverable than its larger opponent. After additional action and reloading, Monitor’s pilothouse was hit, driving iron splinters into Worden’s eyes. Temporarily blinded, Worden turned over command to his executive officer, Lt. S. Dana Greene, and Monitor withdrew into the safety of shoal water. Concluding that Monitor was disabled, Virginia quickly turned to attack Minnesota. However, Virginia’s officers reported the ship was low on ammunition, there was a leak in the bow, and that it was having difficulty keeping up steam. At about 12:30 p.m., Virginia steamed to its yard for repairs and the next day was moved into dry dock. During the night, tugboats finally freed Minnesota from the sand bar. When Virginia failed to appear the following day, it was clear that the battle was over.

Although Virginia’s success on March 8 thrilled the Confederacy and gave it false hope that the Union blockade of Hampton Roads might be broken, there was no clear winner in the duel between the ironclads (although both sides claimed victory). Monitor was able to protect the Hampton Roads blockade force and free Minnesota as ordered, whereas Virginia had been able to sink two larger Union combatants.. After the brief battle, ironclad ships were a prototype for new ship construction. By the end of the Civil War, the Confederacy and Union had launched more than 70 ironclads, signaling the end of wooden warships.

The two ironclads would face off once more on April 11, 1862, near Sewell’s Point, but did not engage. Neither was willing to fight on the other’s terms. The Union wanted the encounter to take place in the open sea while Virginia tried unsuccessfully to lure Monitor farther into Hampton Roads. On May 9, 1862, following the Confederate evacuation of Norfolk, Virginia was scuttled by its crew. Monitor—with 16 crewmembers—was lost during a gale off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, on Dec. 31, 1862.

In 1973, the wreck of Monitor was located off the North Carolina coast and more than 200 tons of artifacts were recovered, including its revolving gun turret, Dahlgren guns, and steam engine. The artifacts are on display at the Mariners’ Museum and Park in Newport News, Virginia. The wreck of Virginia was mostly removed after the war and later salvaged for its iron. Pieces of the ship have been preserved in museums: the Hampton Roads Naval Museum holds in its collection Virginia’s brass bell and one of Virginia’s anchors rests in front of the American Civil War Museum in Richmond.

Missouri’s Bombardment Operations in Korea

From March 14–19, 1951, during bombardment operations off Kyojo Wan, Songjin, Chaho, and Wonsan in support of UN forces during the Korean War, USS Missouri (BB-63) was credited with destroying eight railroad and seven highway bridges, thus contributing significantly to the Fast Carrier Task Force (TF-77) campaign against the enemy’s transportation system. Missouri—the first American battleship to reach Korean waters after North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950—arrived in the area of operations on Sept. 14. Shortly thereafter, Missouri bombarded Samchok in a diversionary move coordinated with the Inchon landings. In company with heavy cruiser USS Helena (CA-75) and two destroyers, Missouri helped prepare the way for the historic Eighth Army offensive. Throughout the war, Missouri participated in multiple bombardment and gunfire support missions during its two extended deployments to the Korean Peninsula. Missouri earned five battle stars for its significant service during the conflict.

Constructed in the midst of World War II, Iowa-class battleship Missouri was commissioned on June 11, 1944. It was the last battleship commissioned by the United States Navy. After trials off New York and battle practice in the Chesapeake Bay, Missouri transited the Panama Canal on its way to the Pacific theater. Missouri then steamed with carriers to Iwo Jima, where its 16-inch guns provided direct and continuous support to the amphibious landings. In March 1945, Missouri was assigned to the Yorktown (CV-10) carrier task force for strikes against targets along the coast of the Inland Sea of Japan. Later that month, Missouri joined the fast battleships of TF-58 in the bombardment of the southeast coast of Okinawa, an action intended to draw enemy strength from the west coast beaches, which would be the actual site of the landings. Missouri rejoined the screen of carriers as U.S. Marines and Soldiers landed on the island on the morning of April 1. During the Battle of Okinawa, Missouri shot down five enemy planes and assisted in the destruction of six others. It helped repel 12 daylight attacks of enemy raiders and fought off four night attacks on its carrier task group. Missouri’s shore bombardment destroyed several gun emplacements and many other military, governmental, and industrial structures. For the remainder of the war, Missouri continually struck targets throughout the Japanese Home Islands. On Aug. 15, President Harry S. Truman announced Japan’s acceptance of unconditional surrender. On Sept. 2, high-ranking military officials of all the Allied Powers, to include Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz and General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, came aboard Missouri to meet Japanese representatives for a 23-minute surrender ceremony that was broadcasted around the world. Missouri earned three battle stars for its World War II service.

Although most remember Missouri as the symbolic end of World War II, it was a highly decorated battleship that earned a total of eight battle stars, two Combat Action Ribbons, two Navy Unit Commendations, a Meritorious Unit Commendation, three Navy “E” Ribbons, two Armed Forces Expeditionary Medals, and one Southwest Asia Service Medal during its nearly 50 years of service to the nation. On March 31, 1992, Missouri was decommissioned and remained part of the reserve fleet until Jan. 12, 1995, when it was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register. Missouri was donated as a museum and memorial ship on May 4, 1998, and today is moored near the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor.

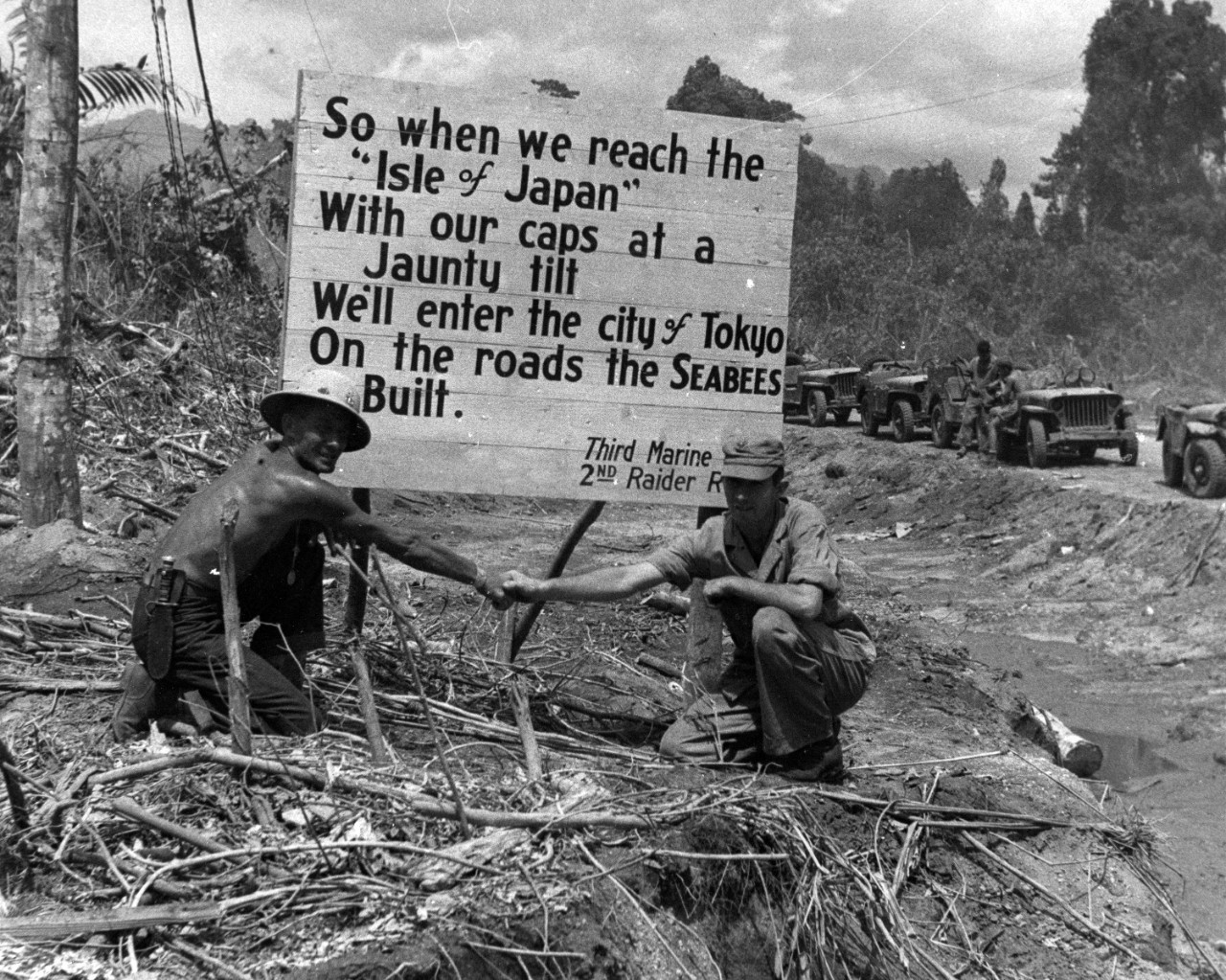

Today in Naval History—Seabees Established

Today, U.S. Navy Seabees celebrate their 82nd birthday. They were founded during the early days of World War II, when Chief of the Bureau of Yards and Docks Rear Adm. Ben Moreell requested specific authority to activate, organize, and staff Navy construction units. The Bureau of Navigation authorized the first Seabee units on Jan. 5, 1942, and official authorization of the Seabees name and insignia occurred on March 5. Rear Adm. Moreell personally furnished the Seabees with their official motto: Construimus, Batuimus— “We Build, We Fight.” Navy construction battalion command was decided on March 19, 1942, when Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox authorized officers from the Civil Engineer Corps authority over construction battalions. The decision constituted a significant morale boost for Civil Engineer Corps officers because it provided a lawful command authority that tied them intimately to combat operations, the primary reason for the existence of any military force.

After the Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States’ subsequent entry into World War II, the use of civilian labor in war zones became impractical. Under international law, civilians were not permitted to resist an enemy military attack. If a civilian resisted, they would be deemed guerrillas and executed. Thus, the need for a militarized naval construction force to build advance bases in war zones was a forgone conclusion. The first Seabees that enlisted were not just recruits off the street. Placing emphasis on experience and skill was essential to adapting their civilian construction skills to the military’s needs. To enlist recruits with the necessary qualifications, physical standards for Seabees were less rigid than in other branches of the armed forces. The age range for enlistment was 18–50, but after the formation of the initial battalions, several recruits over the age of 60 managed to join the Seabees. Thus, during the early days of the war, the average age of a Seabee (37) was much older than that of an average recruit. The first Seabee recruits were construction workers who helped build Boulder Dam (today’s Hoover Dam), national highways, and New York’s skyscrapers. They had worked in mines, quarries, shipyards, docks, and even on ocean liners and aircraft carriers. By the end of the war, 325,000 men had enlisted in the Seabees and mastered more than 60 skilled trades. Nearly 11,400 officers joined the Civil Engineer Corps during the war, with 7,960 serving as Seabees.

During the war, at naval construction training centers and advanced base depots established on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, Seabees were taught military discipline and the use of light arms. Although technically deemed support troops, Seabees, particularly during the early days of base development in the Pacific, frequently found themselves in combat with the enemy while working on a project. After completing three weeks of initial training at Camp Allen, and later at its successor, Camp Peary, both in Virginia, Seabees were formed into construction battalions or other types of construction units. Some of the very first battalions were sent overseas immediately upon completion of boot camp because of the urgent need for naval construction. The usual procedure, however, was to ship a newly formed battalion to an advanced base depot at either Davisville, Rhode Island, or Port Hueneme, California—depending on the theater of operations to which they would be deployed. There, the battalions underwent staging and outfitting. The Seabees received about six weeks of advanced military and technical training, underwent considerable unit training, and then were shipped to an overseas assignment.

As the war progressed and construction projects became larger and more complex, more than one battalion frequently was assigned to a base. For administrative control, Seabee battalions were organized into a regiment; when necessary, two or more regiments were organized into a brigade; and as required, two or more brigades were organized into a naval construction force. For example, 55,000 Seabees were assigned to Okinawa and the battalions were organized into 11 regiments and four brigades, which, in turn, were all under the command of Commander, Construction Troops—led by Navy Civil Engineer Corps officer Commodore Andrew G. Bisset. His command also included 45,000 United States Army engineers, aviation engineers, and a few British engineers. He commanded about 100,000 construction troops in all, the largest such concentration during the entire war.

Seabee operations in the Atlantic theater began in March 1942 with construction projects in Iceland, Newfoundland, and Greenland. Seabees helped develop the installations at Argentia, Newfoundland, used by aircraft and surface ships deployed to protect Allied convoys in the western sector of the North Atlantic. During the invasion of Sicily, Seabee pontoons helped the Allies execute surprise attacks. At Normandy, Seabees worked with U.S. Army engineers to destroy steel and concrete barriers for the amphibious landings. The construction battalions also worked to emplace the huge offshore port area known as Mulberry A to support the D-Day landings.

Using Sailors to build shore-based facilities was not a new idea. From the earliest days of the U.S. Navy, Sailors who were handy with tools occasionally did minor construction chores at land bases. American seamen were first employed in large numbers for major shore construction during the War of 1812. In 1813, the frigate Essex, under the command of Capt. David Porter, rounded Cape Horn and became the first Navy ship to carry the American flag into the Pacific Ocean. While operating in the Pacific, Essex captured a British commerce raider, several British merchantmen, and several large British whaling ships. While sailing near the Galapagos Islands in October 1813, Porter learned that a British naval squadron had entered the Pacific and was searching for Essex. To prepare his squadron for battle, Porter needed a safe harbor to repair and re-equip his ship and some of the captured prizes that had been converted into fighting vessels. In the absence of secure facilities on South America’s west coast, he decided to take his ships to the Marquesas Islands. After sailing through the Marquesas for a few days, he selected Nukuhiva Island as the best site for constructing the Navy’s first advanced base. Under Porter’s direction, nearly 300 skilled craftsmen from his ships undertook the building of the base. Approximately 4,000 natives helped obtain the materials and worked side by side with the American Sailors. As protection against unfriendly tribes and the British, the Sailors built a fort, which was duly christened Fort Madison with the ceremonious raising of the American flag. Upon its completion, the Navy’s first advanced base was named Madison’s Ville.

Since the Seabees were officially established during World War II, they have participated in every major American conflict and numerous humanitarian disaster relief operations around the world since that time. They have been the Navy’s construction force, building bases and airfields, conducting underwater construction, and building roads, bridges, and other support facilities. Their “can do” attitude plays a crucial role in supporting the fleet and combatant commands while carrying out the Navy’s maritime strategy. Happy Birthday, Seabees!

For more on the history of the Seabees, visit Naval History and Heritage Command’s Seabee Museum in Port Hueneme, California. On its website, there is a plethora of information on Seabee unit histories, World War II cruise books, and much more.