Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

McMullen Naval History Symposium

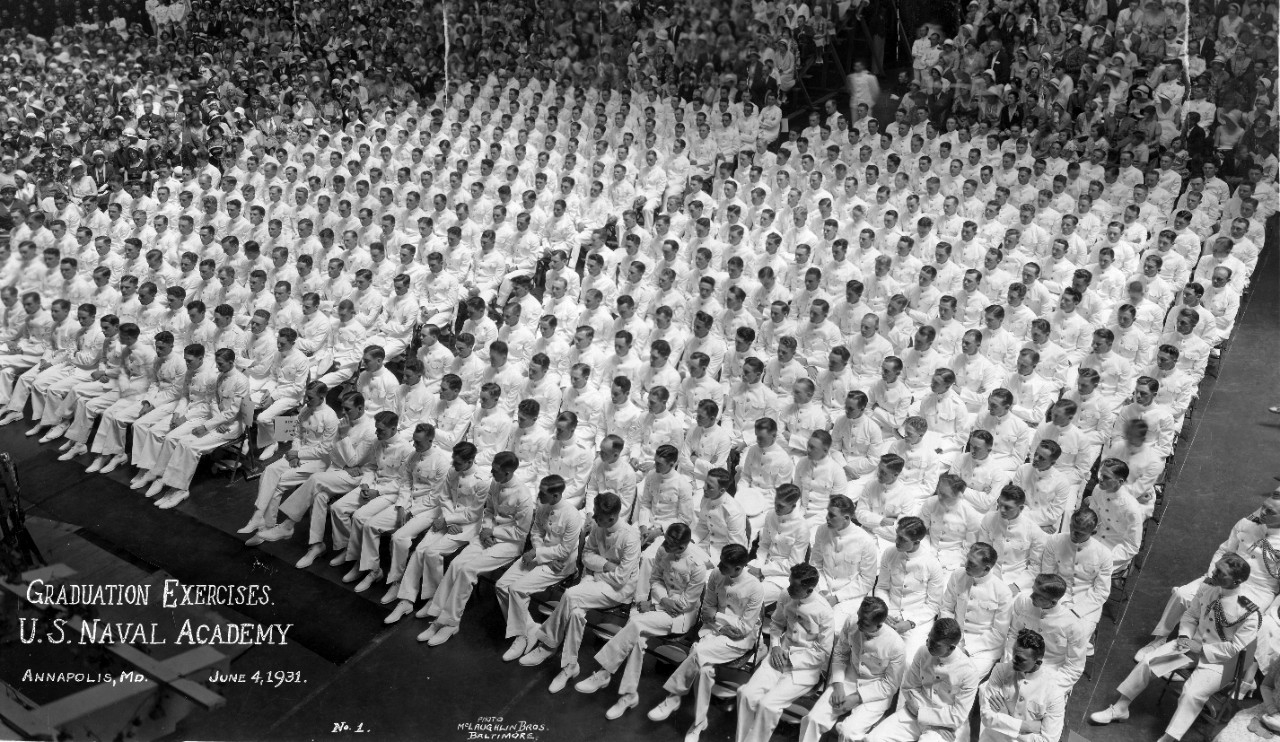

The McMullen Naval History Symposium is scheduled for Sept. 21–22, 2023, at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. Registration is free and remains open, but you must register to attend this event. Representatives from the Naval History and Heritage Command will be presenting at multiple sessions as part of the conference program. The symposium, hosted by the academies history department, is held biennially to highlight the latest research on naval and maritime history from academics and practitioners from all over the globe. Since 1973, the annual symposium has been described as the “largest regular meeting of naval historians in the world,” and as the U.S. Navy’s “single most important interaction with an academic historical audience.”

The two-day event will cover a wide variety of topics from privateers and prisoners of war during the age of sail to remembering the Maine to talks on the nuclear Navy. NHHC personnel will be participating in the sessions on both days. To view the complete list of sessions, click here. To register for the event, click here.

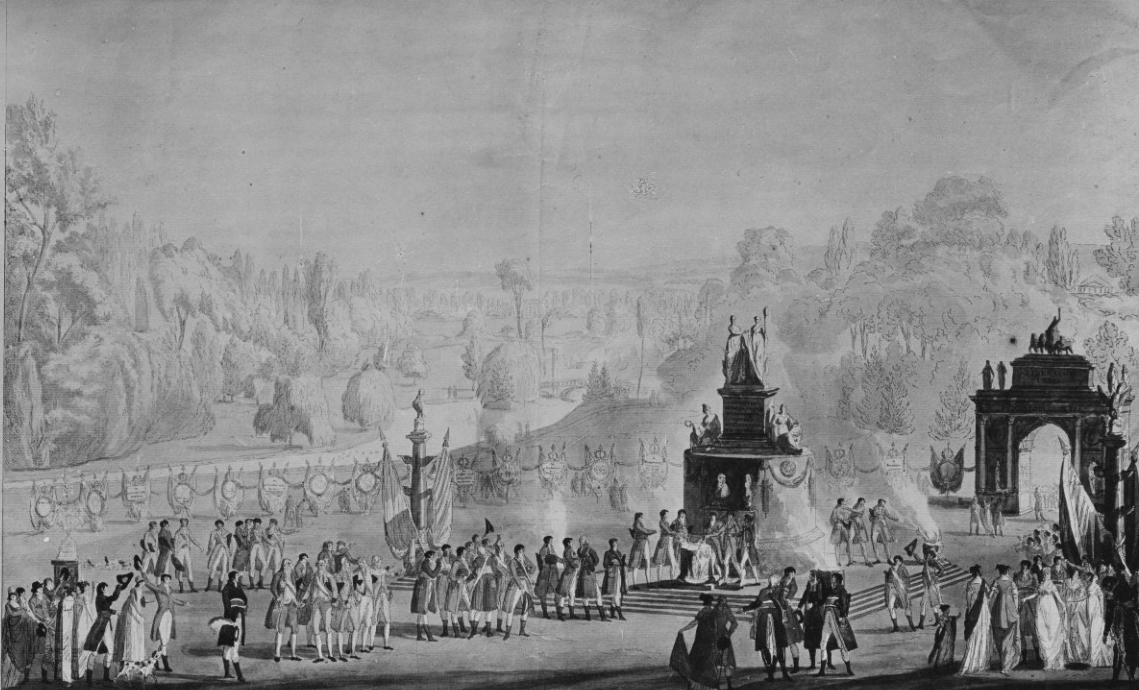

Quasi-War with France Formally Ends

On Sept. 30, 1800, French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, along with representatives from the United States, signed the Treaty of Mortefontaine, which released the United States from its American Revolution alliance with France and ended the so-called maritime Quasi-War with mostly French privateers. The agreement negated the Treaty of Alliance, signed on Feb. 6, 1778, and reasserted the United States’ right to free trade on the open seas. Leading up to the Quasi-War with France and after gaining independence from Great Britain, the newly formed U.S. government had its first real test on the global stage with its former ally. The Quasi-War centered on American trading rights as a neutral nation. The conflict was an offshoot of the ongoing conflict between Britain and France, and it was primarily a limited naval engagement against the French, who were seizing U.S. shipping. The Quasi-War was significant as it was the first seaborne conflict for the reestablished U.S. Navy and the first actions to protect U.S. shipping abroad. Although American ships did clash with French naval warships on several occasions, these were rare and war was never formally declared on the French government.

The French monarchy that had forged the alliance with the United States was overthrown during the French Revolution. For about a decade, France swung dramatically from a traditional monarchy to a country that seemed prepared to overthrow every other empire in Europe. In 1792, war broke out between France and Great Britain. The British viewed revolutionary France as a threat, and subsequently the relationship between the United States and France also soured. When France declared war on Britain and the European coalition, the United States declared its neutrality. During this time, the United States was trying to establish itself as a neutral international trading partner. When peace with Britain had been declared through the Treaty of Paris in 1783, America enjoyed some prosperity, but the treaty still left many issues unresolved. American merchants were still unable to trade with Britain’s remaining colonies in the Caribbean, which had been a major market for American merchants. To resolve the outstanding issues with Britain, the United States began negotiating a new agreement, known as the Jay Treaty. After the treaty was signed on Nov. 19, 1794, relations with Britain improved, and the United States viewed itself a neutral country. However, France viewed the Jay Treaty as a negation of America’s earlier treaties with France. If American merchants were going to trade with France’s enemies, France was going to treat them like enemies. French privateers began seizing U.S. merchant ships trading with Britain and its colonies, even taking ships off of the U.S. East Coast. Between October 1796 and July 1797, more than 300 American merchant ships and their cargos were seized in the greater Caribbean. In response, the United States suspended payments of war debts to France, thus moving the two nations closer to a conflict.

In an effort to resolve the dispute diplomatically, President John Adams established a commission of three American diplomats that were to meet with France’s minister of foreign affairs, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord. Over the course of several months between 1797 and 1798, the American commission struggled to even meet with the French foreign minister. Instead, it was diverted toward a group of mid-level officials who demanded excessive bribes, loans, and other concessions. The members of the American commission disagreed with each other on how to proceed, and they eventually came home without being able to meet President Adams’ goals. Adams feared the diplomatic failure would push the United States to war, but he recognized the need for defensive measures. While reporting to Congress, Adams initially refused to turn over the original dispatches from the commission. When he eventually did, he redacted the names of the French officials, instead labeling them “W,” “X,” “Y,” and “Z.” As a result, the failed diplomatic mission became known as the XYZ Affair.

News of the XYZ Affair provoked the United States to act. Although highly disputed in earlier debates, support grew for funding an American navy to protect free trade and defend U.S. merchants against French privateers. In 1794, an act to provide a naval armament was signed that included the authorization for the construction of the U.S. Navy’s six original frigates. When the Quasi-War with France began, the frigates were in various stages of construction and outfitting. To meet the interim need, merchant ships and revenue cutters were converted to warships to confront the French. The converted ships initially patrolled the American coastline, where privateers were known to seize merchant vessels. Beginning in 1798, frigates Constellation, Constitution, and United States were deployed to the Caribbean and took up stations off the main trading ports and in the heavily travelled passages among the islands. Chesapeake joined the effort in 1800.

Overall, the mission in the Caribbean was successful. With only about 16 ships in its fleet, the Navy captured 86 French privateers between 1799 and 1800. The U.S. vessels were unofficially assisted by the presence of the British Royal Navy in the region. Although the British did not capture as many privateers as the Americans, they posed a threat to French naval forces and guarded convoys of British ships in and out of the region. Despite its successes, however, the U.S. Navy did suffer from failures of organization and management during the Quasi-War. With no infrastructure in place for supplying the new ships, deployments were often delayed due to lack of personnel and materials. Ship captains frequently struggled to negotiate the complex laws regarding which ships could be legally seized. Although the Treaty of Mortefontaine reopened the door to better American trade opportunities with both France and Great Britain in the Caribbean, the central issues of neutral American trade with warring European countries would come to the forefront again during the War of 1812.

Nautilus Commissioned

On Sept. 30, 1954, the world's first nuclear-powered submarine, USS Nautilus (SSN-571), was commissioned at Groton, Connecticut. The construction of Nautilus was made possible by the successful development of a nuclear propulsion plant by a group of scientists and engineers under the leadership of then-Capt. Hyman G. Rickover. Following commissioning, Nautilus remained dockside for further construction and testing for the next several months. On Jan. 17, 1955, it was underway. After sea trials and preliminary acceptance by the Navy, Nautilus headed south for shakedown. While en route to Puerto Rico, it remained submerged, traveling 1,381 miles in 89.8 hours, the longest submerged cruise to that date by a submarine and at the highest sustained submerged speed ever recorded for a period of more than one hour’s duration. In July–August 1955, Nautilus conducted rigorous exercises with hunter-killer groups in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, and off Bermuda. It rounded out the year visiting several U.S. East Coast bases. The following year, Nautilus operated out of Naval Submarine Base New London, Connecticut, where the effects of a submarine with increased speed and endurance were tested on contemporary anti-submarine warfare practices. The study found that anti-submarine practices, such as were used during World War II, were ineffective against a submarine that did not need to surface, dived deeper, and cleared search areas in record time.

On Feb. 4, 1957, Nautilus logged 60,000 nautical miles. It also marked another first for the boat, as the submarine was put into the Electric Boat Company Division of General Dynamics Corporation at Groton to replace the nuclear fuel core in its Westinghouse Electric submarine thermal reactor. In early April, Nautilus operated off Bermuda with USS Seawolf (SSN-575)—the second nuclear-powered submarine—before departing for the U.S. West Coast in May. While there, Nautilus participated in multiple exercises designed to acquaint the units of the Pacific Fleet with the capabilities of nuclear submarines. On Aug. 19, Nautilus departed its homeport for its first voyage under the Arctic polar ice pack. The 1,383-mile journey was significant, because previous U.S. diesel-electric submarines did not travel to the frozen northern oceans as they could not travel freely under ice. The opening of the Arctic to Navy submarines allowed access to the previously protected waters of the Soviet Union. From the Arctic, Nautilus steamed to the eastern Atlantic to participate in NATO exercises off Norway and to visit various British and French ports. Nautilus returned to New London in late October where it underwent upkeep.

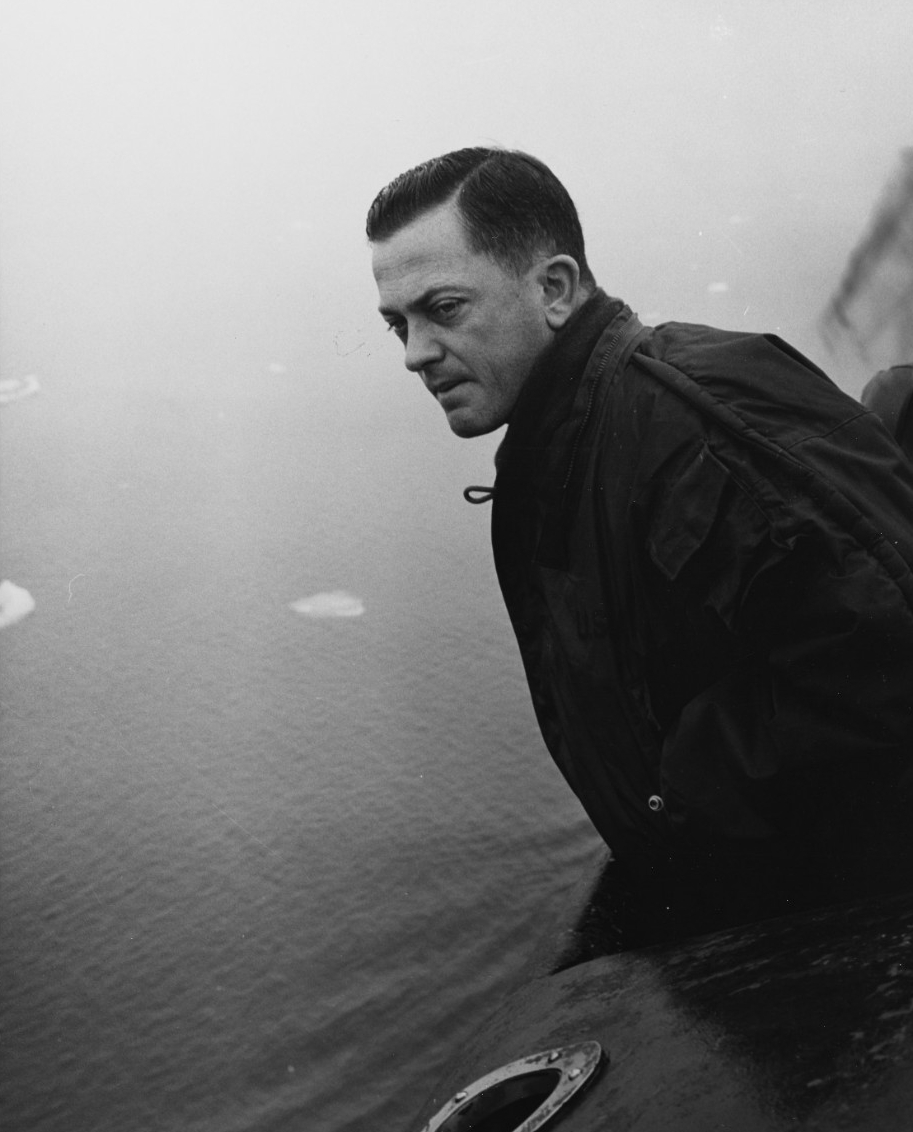

On April 25, 1958, Nautilus was once again headed for the U.S. West Coast, where it made stops in San Diego, San Francisco, and Seattle. On June 9, Nautilus departed the Pacific Northwest to conduct the highly secret “Operation Sunshine,” a fully submerged transit under the North Pole. However, the first attempt was blocked by drift ice in the relatively shallow waters of the Chukchi Sea, and the submarine made way to Pearl Harbor. Its second attempt in late July proved successful. Nautilus submerged in the Barrow Sea on Aug. 1, transited the geographic North Pole on Aug. 3, and, after running submerged an additional 96 hours, surfaced off Greenland on Aug. 7. The commanding officer, Commander William R. Anderson, and the crew were subsequently personally congratulated by President Dwight D. Eisenhower and awarded the Presidential Unit Citation.

By 1961, the Navy had about a dozen nuclear-powered submarines in service. Nautilus continued to focus on evaluation tests for anti-submarine warfare improvements and various NATO exercises in the Atlantic. The pattern was broken in the fall of 1962, when Nautilus participated in the quarantine of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis. In August 1963, Nautilus headed east again for a two-month Mediterranean tour before heading to Portsmouth for an extensive overhaul. The overhaul took 27 months to complete. The submarine returned to homeport in May 1966. Over the next six years, Nautilus participated in several fleet exercises while steaming more than 200,000 miles. In the spring of 1966, it again entered the record books when it logged 300,000 miles underway. During the following 12 years, Nautilus was involved in a variety of developmental testing programs while continuing to serve alongside many of the more modern nuclear-powered submarines it had preceded.

On April 9, 1979, Nautilus departed Groton on its final underway, steaming south to the Panama Canal via Guantanamo Bay and Cartagena, Columbia. From there, it cruised north and reached Mare Island Naval Shipyard, Vallejo, California, on May 26, to begin inactivation procedures. The ground-breaking submarine decommissioned on March 30, 1980. In recognition of its pioneering role in the practical use of nuclear power, Nautilus was designated a National Historic Landmark by the Secretary of the Interior on May 20, 1982. Following an extensive historic ship conversion at Mare Island, the submarine was towed to Groton, arriving on July 6, 1985. There, on April 11, 1986, 86 years to the day after the establishment of the U.S. submarine force, historic ship Nautilus and the Submarine Force Museum opened to the public as the first exhibit of its kind in the world. The unique museum ship continues to serve as a dramatic link in both Cold War-era history and the birth of the nuclear age.

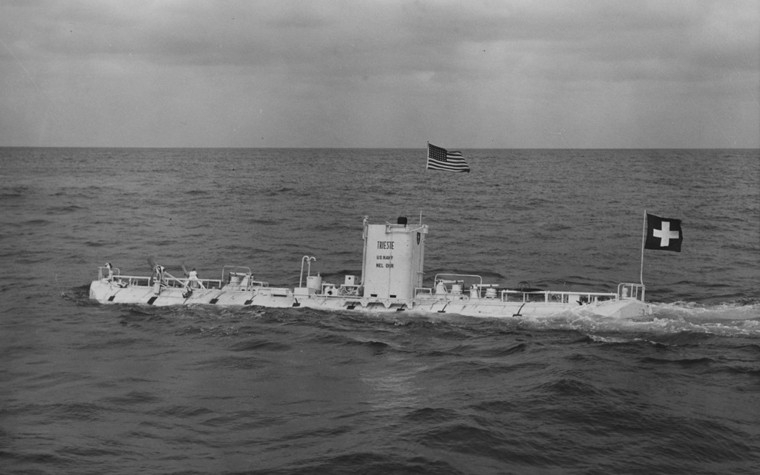

Today in Naval History—Bathyscaphe Trieste

On Sept. 19, 1957, bathyscaphe Trieste, in a dive sponsored by the Office of Naval Research, reached a record depth of two miles in the Pacific. After the descent and a series of tests and examinations, a group of American oceanographers and underwater sound specialists recommended that the craft be acquired by the United States government. They thought that the submersible was the ideal vessel for Project Nekton, an inspection of the deepest point in the world's oceans, the Challenger Deep in the Pacific off the Marianas. Thus, in the fall of 1958, Trieste was acquired and transported to San Diego, its new homeport. Starting in December of that year, Trieste made several dives off the southern California coast. Fitted with a stronger sphere, fabricated by the Krupp Iron Works of Germany, Trieste was taken to Guam for Project Nekton. On Jan. 23, 1960, with Lt. Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard, son of the bathyscaphe’s designer, at the helm, Trieste descended seven miles to the bottom of the Challenger Deep. The world-record descent took nine hours.

Following the historic dive, the bathyscaphe was overhauled and then conducted a number of dives out of the San Diego area supporting Navy research objectives. In April 1963, nuclear submarine Thresher (SSN-593) was lost with all hands off the Massachusetts coast. Trieste was subsequently transported across the country to Boston where it began to search for the lost submarine. After a number of dives, Trieste discovered debris from Thresher 220 miles off Cape Cod that included the submarine’s sail, which clearly showed Thresher’s hull number “593.” For its part in the Thresher search, the bathyscaphe and its commander received the Navy Unit Commendation. After the search mission was complete, Trieste was taken out of service and returned to San Diego. In early 1980, the bathyscaphe was transported to the Washington Navy Yard, where the vessel was placed on exhibit at the National Museum of the U.S. Navy.