Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

V-J Day

On Sept. 2, 1945, more than two weeks after accepting the Allies’ terms, Japan formally and unconditionally surrendered, marking the end of World War II. During the brief 20-minute ceremony, the instrument of surrender was signed by representatives of the Allied and Japanese governments onboard USS Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay. Japanese Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signed on behalf of the Japanese government, and Gen. Yoshijiro Umezu signed for the Japanese armed forces. For the Allies, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur signed next, followed by signatures of senior officers from the United States, China, Britain, the Soviet Union, Australia, Canada, France, the Netherlands, and New Zealand. Fleet Adm. Chester W. Nimitz signed for the United States. Afterward, millions around the world erupted in celebration. The bloodiest conflict in human history was finally over.

Leading up to Japan’s surrender, the Japanese navy and air force were completely devastated, and with the successful campaigns on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, the Allies were just steps away from Japan’s home islands. In addition, shortages of food, fuel, and strategic materials left both the Japanese military and civilian populace in dire straits. The Imperial Japanese Navy no longer had enough fuel in their reserves to go to sea. Strict conservation of aviation fuel grounded most of Japan’s aircraft. Moreover, the Soviet Union refused to renew its neutrality pact with Japan. The defeat of Japan was a foregone conclusion.

During the previous months, as the Allies prepared for an invasion of Japan (codenamed Operation Downfall), President Harry S. Truman had asked his top advisors what they believed the cost of lives would be in the invasion. Some estimated it could be up to one million Allied and Japanese lives lost. On July 16, a new option became available when the United States detonated the first atomic bomb at the Trinity test site at Alamogordo, New Mexico. Ten days later, the Allies issued the Potsdam Declaration, demanding the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces. Terms included complete disarmament, occupation of certain areas, and the creation of a “responsible government.” It also promised that Japan would not be enslaved as a race or destroyed as a nation. The declaration ended by warning of “prompt and utter destruction” if Japan failed to unconditionally surrender. In late July, Japanese Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki responded by telling the press that the Japanese government was “paying no attention” to the Allied ultimatum. At that point, President Truman made the tough decision and ordered an atomic bomb to be dropped on Japan. On Aug. 6, U.S. B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped “Little Boy” on Hiroshima, killing an estimated 90,000 to 120,000 Japanese. To further complicate matters for Japan, the Soviet Union declared war on that nation the next day.

After the devastation of the Hiroshima attack, a faction in Japan’s supreme war council favored the acceptance of the Allies’ terms. However, believing the United States only had one atomic bomb, the majority of the council resisted an unconditional surrender. On Aug. 9, a second atomic bomb, “Fat Man,” was dropped on the large port city of Nagasaki, killing an estimated 129,000 to 226,000 Japanese. In the aftermath, Emperor Hirohito called an imperial conference of all high-level advisers to discuss an unconditional surrender. Although there were disagreements, on Aug. 10, Emperor Hirohito relayed a message to the United States that Japan would surrender unconditionally. On Aug. 14, Hirohito’s surrender announcement to the Japanese nation was recorded. Despite an attempted last-minute coup by radical militarists, the message was broadcasted the next day. Of note, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and the United Kingdom celebrate V-J Day on Aug. 15—the day Emperor Hirohito’s surrender message was broadcasted to the Japanese people on Radio Tokyo.

Tidal Waves Slam Memphis

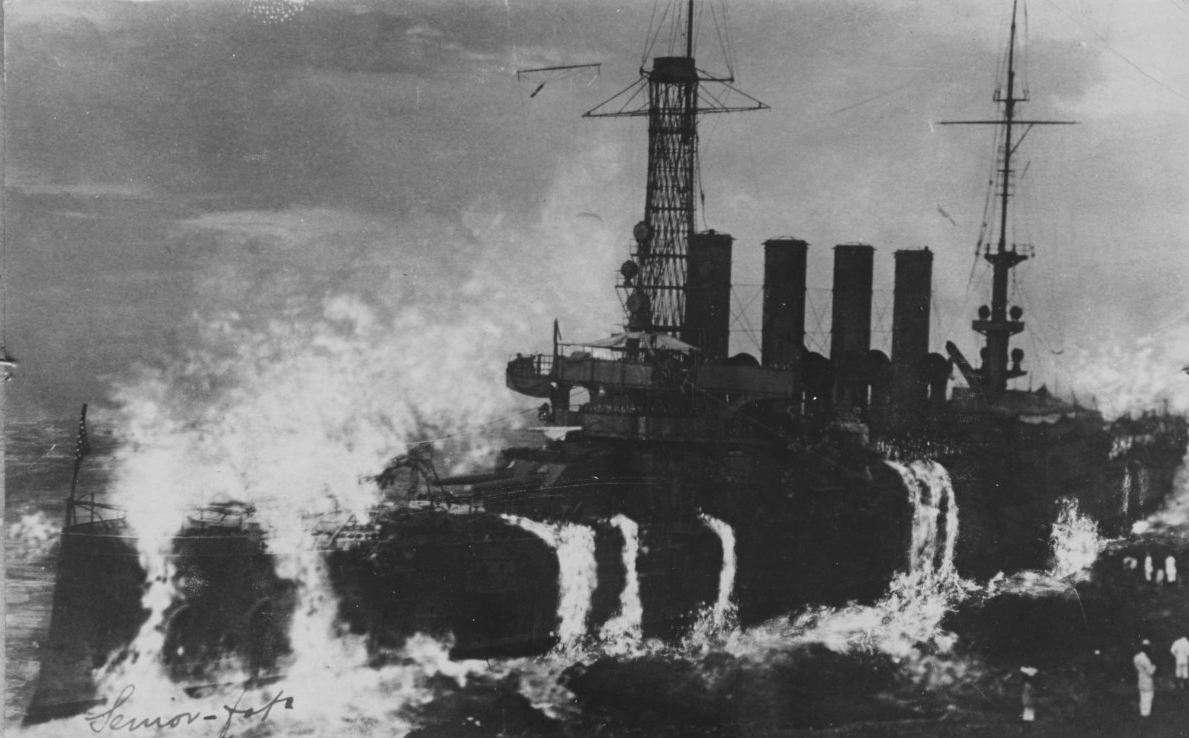

On the afternoon of Aug. 29, 1916, in the harbor of Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, armored cruiser Memphis and gunboat Castine were at anchor. At approximately 3:30 p.m. a series of tidal waves inundated the port, driving Memphis ashore and almost wrecking Castine. The waves were so steep, reportedly 75 feet high, that they flowed over the armored cruiser, including the bridge and even the stacks, and repeatedly battered the warship into the bottom of the harbor. The massive waves swamped Memphis as Sailors in the engine and fire rooms tried in vain to power up the steam engines to get the ship underway. Castine survived the storm by steaming out to sea. In less than two hours, Memphis was wrecked. Above the waterline the ship didn’t appear to be damaged, but below the surface, the ship’s hull was crushed, conforming to rocks and coral on the bottom. The lower decks were flooded almost to the waterline, leaving Memphis stranded in shallow water. The crew battled to save the ship, but the sea’s abrupt destructive power proved to be too much. Along with the loss of the ship, 43 Sailors were killed and many more wounded. Three Sailors were later awarded the Medal of Honor for their heroic actions on that day—Commander Claud Ashton Jones, Chief Machinist’s Mate George William Rud (posthumously), and Machinist Charles H. Willey. The wreck of Memphis remained on the shore of Santo Domingo until 1937, 21 years later, when sufficient ship-breaking capability became available to safely salvage it.

Originally commissioned at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on July 17, 1906, as Tennessee, the ship served as an escort on its maiden voyage for Louisiana (Battleship No. 19), which had President Theodore Roosevelt onboard for a tour of ongoing work on the Panama Canal. After the cruise was complete, both ships made way to Hampton Roads, Virginia, and after repairs, Tennessee was present at the Jamestown Exposition, held off Sewell’s Point, Norfolk, to commemorate the tricentennial of the founding of the first permanent English settlement in America. After several cruises in the Atlantic, Tennessee was reassigned to the Pacific Fleet in late 1907. The ship operated in Pacific waters for several years before it was reassigned again, this time as the flagship for the 5th Division of the Atlantic Fleet. Tennessee operated in the Atlantic until joining the Reserve Fleet in Philadelphia in October 1913, where it remained inactive until the outbreak of World War I. Over the course of the war, Tennessee, among other missions, was instrumental in evacuating thousands of refugees from Jaffa, Palestine, and helped quell ongoing violence in Haiti.

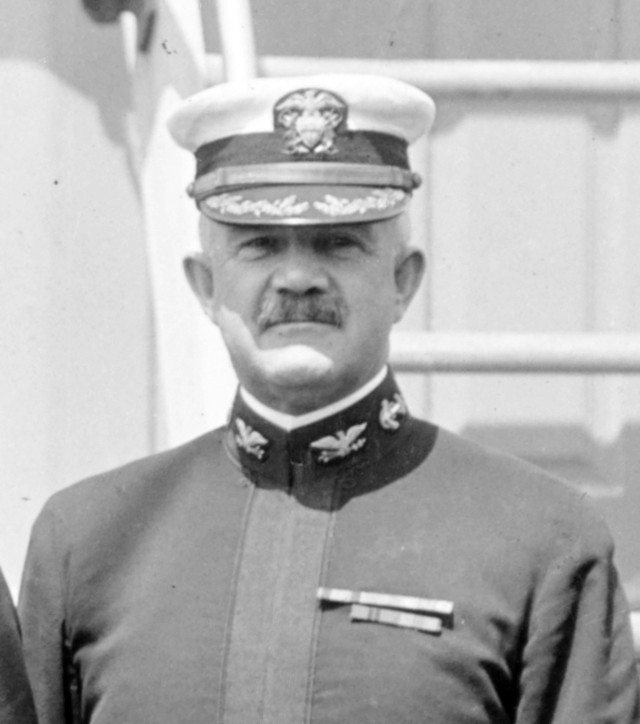

After the Naval Act of 1916 was passed, President Woodrow Wilson’s request to “build a navy equal to any other in the world,” included ten additional battleships, one of which (Battleship No. 43) was slated to be named Tennessee. Consequently, on May 25, Tennessee was renamed Memphis, honoring the city in western Tennessee. About a month later, Capt. Edward L. Beach, Sr., took command of Memphis and was underway for the West Indies, arriving at Santa Domingo on July 23 for a peacekeeping patrol off the rebellion torn republic.

In the month after Memphis was wrecked by the storm, the Navy held three inquiries into the incident. All three investigations were conducted in the first few weeks of September 1916. The significant findings included the following: 1. between 4:20–4:30 p.m., the heavy rolling of Memphis caused water spray to enter the stacks, hampering attempts to power up the engines to get underway; 2. there had been a tropical disturbance, which passed south of Santo Domingo during the night before the tragedy. The disturbance produced no wind or other markers of severe weather, but “produced the heavy swells, which coming in from the deep water to the shallow water of Santo Domingo City anchorage, caused heavy seas that eventually dragged and wrecked Memphis”; and 3. the captain of the ship should have given the order to raise steam to power the engines earlier, anchored Memphis in a safer anchorage, and taken steps to save the ship and recognize the emergency sooner.

Beach was later convicted by court-martial of “not having enough steam available to get under way on short notice,” but the charge was widely regarded as unwarranted and he continued to serve in various assignments for the remainder of his naval career. Before he retired from the Navy in September 1921, he was commandant of the Naval Torpedo Station at Newport, Rhode Island; in 1917 and 1918, commanded New York (Battleship No. 34) during the final months of the “Great War;” and ended his active career as commandant of the Mare Island Navy Yard in California. Subsequently, his son, Capt. Edward L. Beach, Jr., carried on the family tradition of high-profile naval careers. He was a decorated submarine officer during World War II, and as commander of USS Triton (SSR(N)-586), completed the first submerged circumnavigation of the earth in 1960.

Last Navy Airship Flight

On Aug. 31, 1962, the last flight of a Navy airship was made at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey. The ceremonial flight was attended by many former airship crewmembers from around the country, and they participated in docking the airship after the final journey. The Secretary of the Navy had announced he was going to terminate the lighter-than-air program about a year earlier, and by the end of October 1961, ZP-1 and ZP-3, the last operating units of the Navy’s lighter-than-air branch, were disestablished.

The Navy launched its lighter-than-air program when it awarded its first contract for an airship, DN-1, to the Connecticut Aircraft Company in June 1915. During construction of the craft, the Navy also authorized the manufacture of a hangar to house the new airship, which was completed in early 1916. DN-1 arrived in Pensacola, Florida, in December 1916, but the airship was not ready for flight until April 1917. Once test flights began, multiple problems were revealed. Ultimately, the airship was severely damaged during one of its test flights, and the project was abandoned.

Even before DN-1 was built, studies were ongoing at the Bureau of Construction and Repair for a future class of airships. In April 1916, the General Board endorsed the development of zeppelins and other mobile lighter-than-air craft. At Akron, Ohio, the Navy’s program tested non-rigid airships, free balloons, and kite balloons. During testing, the balloons were found to be an easy target for enemy aircraft, and they restricted maneuverability when moored to a ship. During World War I, airships and kite balloons were used in conjunction with seaplanes and flying boats to help protect shipping. They were also used to detect submarines and warn vessels of mines. Most of the airship patrols were carried out off the U.S. East Coast and in Europe, where they were deemed successful because they were a deterrent to the threat of German U-boats.

After the Great War, the development of non-rigid airships became more advanced to include additional capabilities. The Navy contracted Goodyear to build airships, and hangers were built to accommodate them. The airship Shenandoah (ZR-1) was the first rigid airship to be inflated with helium and was first to fly across the United States. On Sept. 3, 1925, while flying over Ohio, Shenandoah ran into a severe storm that broke the airship in two, killing almost half the crew. The most successful airship of the time was USS Los Angeles (ZR-3). The airship was originally built by Germany and handed over to the United States as compensation for two U.S. airships that were lost during the war. Los Angeles was in operation more than seven years and made more than 330 flights.

Probably the most prolific period in the Navy’s construction of rigid airships was during the era of Akron and Macon. They were viewed as an improvement over the Shenandoah design, having the ability to house and carry small fixed-wing aircraft. However, they were to be the first and last flying aircraft carriers. Akron was lost in 1933 off the coast of New Jersey during a storm with the loss of 73, and Macon was lost with 83 of its crew off the Santa Barbara Islands.

During World War II, there were five different airship classes/types in the Navy’s inventory. Airship operations and expansion was unprecedented. The airship fleet conducted operations in the Pacific, Mediterranean, and south Atlantic. When the war was over and the military drew down, the Navy still retained two squadrons that conducted mostly training, search and rescue, observation, and photography missions. For more on airships and dirigibles, visit NHHC’s website.

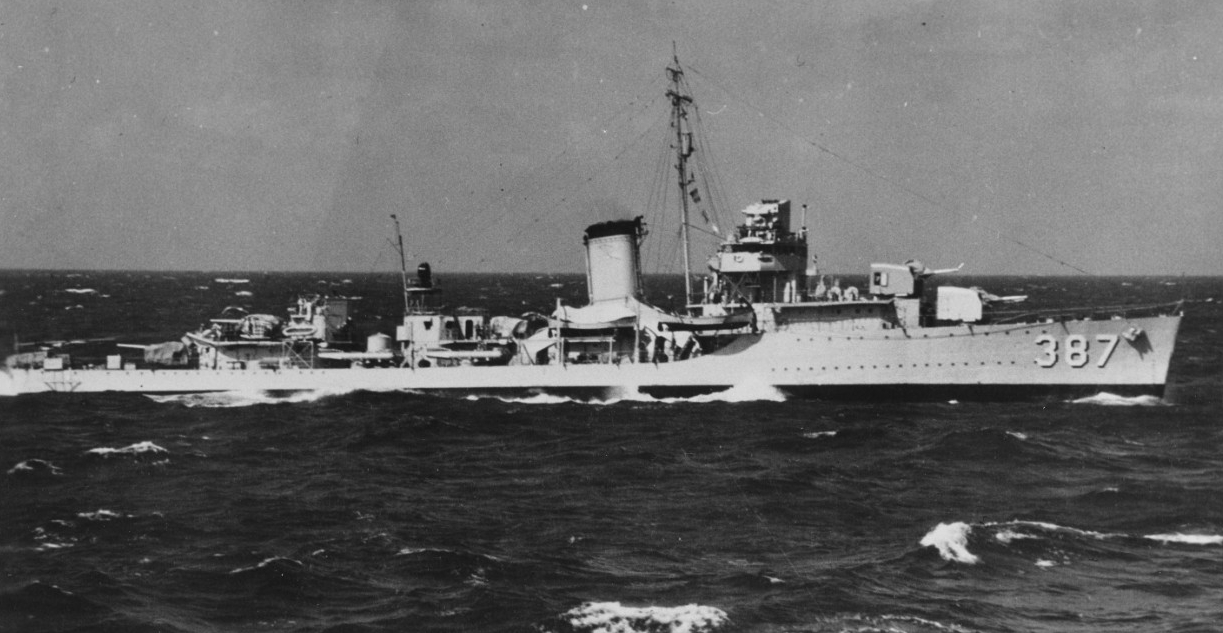

Today in Naval History—Blue Torpedoed, Scuttled

On Aug. 22, 1942, USS Blue (DD-387) was torpedoed by Japanese destroyer Kawakaze off Guadalcanal. The torpedo penetrated 10 feet into the ship before exploding. It threw members of the crew and equipment as high as 50 feet in the air and sent flaming objects flying over the bridge. Blue was able to recover one man blown overboard, but nine were killed and 21 wounded. The ship’s mangled stern was mostly blown off, barely hanging off of the keel, and several compartments flooded or buckled. The explosion also broke the propeller shafts, leaving Blue dead in the water until it was taken under tow by USS Henley (DD-391). The damage to Blue could be isolated, therefore the rest of the ship continued to function and remained watertight. The commanding officer of Blue, Lt. Cmdr. Harold Williams, transferred to Henley to bring the ship closer to shore and safety. Unfortunately, the mangled stern dragged in the water, limiting the ships to just 3.5 knots. Even worse, Henley’s 10-inch manila towline parted just over an hour after being attached. Blue was ordered to proceed to Tulagi for repairs, and Henley reattached a new towline. Still limited to just 3.5 knots, the new line lasted only five hours, snapping in the early evening. Henley then tried a thick steel cable; however, this had to be dropped in the evening due to the sighting of a possible enemy submarine. Henley patrolled for submarines while six landing craft from Tulagi tried, unsuccessfully, to tow Blue. Sailors from Blue, high-speed transport Manley (APD-1), and assorted smaller craft attempted to tow the destroyer to Tulagi the following day, but towlines repeatedly parted or had to be dropped for fear of submarines.

While attempting to tow the ship could have continued somewhat indefinitely, it was drifting and the Japanese were expected to return that night. Henley resumed towing Blue, but was unable to go fast enough to tow it out of Iron Bottom Sound before the Japanese were projected to return. At 8:30 p.m., permission to scuttle the ship was requested, and 20 minutes later, Henley dropped its towline. Blue’s crew opened all watertight doors and prepared the ship for scuttling. The ship was abandoned about an hour later but remained stubbornly afloat. Henley fired a torpedo at Blue, but missed, before opening up with its 5-inch guns. Henley fired nine 5-inch rounds into Blue, which sank quickly, stern first. The bow disappeared under the waves shortly afterward. Today, Blue still rests in 340 fathoms of water in Iron Bottom Sound, 10 miles north of Lunga Point, Guadalcanal. Although Blue’s service during World War II was short—just nine months—it earned five battle stars.

Commissioned on Aug. 14, 1937, it was the first ship named for Rear Adm. Victor Blue, who conducted intelligence reconnaissance missions during the Spanish-American War and later in his career served as chief of the Bureau of Navigation. After commissioning, Blue participated in a number of fleet exercises before being transferred to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, as part of the Pacific Fleet’s buildup. On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, most of Blue’s crew was ashore as the ship was moored about a mile away from Battleship Row. Although Blue had just a skeleton crew aboard, they fought magnificently, shooting down two Japanese planes and possibly attaining depth charge hits on two enemy midget subs. Blue was not seriously damaged during the attack, although four Japanese planes did attack the ship.

On Aug. 7, 1942, Blue, as part of Task Force 62 (TF 62), spotted Guadalcanal Island. TF 62’s mission was to transport components of the 1st and 2nd Marine Divisions to Guadalcanal. Blue screened the fleet as the landing went forward with minimal problems. It continued the following day. At approximately 11:30 a.m., Blue received intelligence that 40 twin-engine Japanese bombers were on their way to the area of operations. As the enemy aircraft began to approach, Blue moved to bring its anti-aircraft guns to bear and opened fire. Blue’s flak crews were somewhat restricted by HMAS Canberra and had to shift fire three times to avoid hitting the Australian cruiser. In the engagement, Blue expended 135 rounds of 5-inch and 200 rounds of 20-millimeter. Blue also rescued four downed Japanese airmen during the battle. The ship’s crew claimed that two planes fired upon “were seen to falter and turn away from the vicinity of bursts” and that five additional crashes occurred after Blue ceased fire.

During the night of 8–9 Aug., a Japanese force of five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and one destroyer, commanded by Vice Adm. Mikawa, were heading past Savo Island with the intent of sinking the Allied force landing supplies at Guadalcanal. Early on 9 Aug., a lookout on one of the cruisers spotted Blue. The Japanese warships slowed, turned slightly away, and trained their weapons on Blue, waiting to see if the destroyer had spotted them. Blue steamed within 11,000 yards of the Japanese cruisers before turning around on its patrol route. Once past Blue and Ralph Talbot (DD-390), Mikawa’s warships proceeded to sink heavy cruisers Vincennes (CA-44), Quincy (CA-39), Astoria (CA-34), and HMAS Canberra, killing over a thousand Allied sailors during the Battle of Savo Island. Blue rescued 343 of Canberra’s surviving crew. The destroyer continued to screen the Marines on the ground and to escort ships until it was sunk about two weeks later.