Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Battle of Tarawa—80 Years Ago

On Nov. 20, 1943, during the Battle of Tarawa, Vice Adm. Raymond A. Spruance’s Fifth Fleet landed approximately 35,000 troops from the 2nd Marine Division and the Army’s 27th Infantry Division on Tarawa’s Betio Island and Makin Atoll in the Gilbert Islands. At the time, it was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific during World War II. Codenamed Operation Galvanic, the assault was part of the Allied “island hopping” campaign to take control of Japanese outposts on enemy-held Pacific islands. The strategy would allow Allied forces to eventually establish air supremacy and a series of bases throughout the Pacific, providing stepping stones to the strategically located Marshall and Marianas island chains in the central Pacific and ultimately Japan’s mainland. While a light Japanese defense on Makin led to less resistance and fewer casualties, the heavily fortified and concentrated defenses on Betio Island led to a long and costly fight. On the morning of D-Day, following naval bombardment, the first wave of Marines approached Betio’s northern shore in transport boats. The Marines encountered lower tides than expected and were forced to abandon their landing craft on the reef that surrounded Betio and wade hundreds of yards to shore under intense enemy fire. When the Marines finally reached the beach, they struggled to move past the seawalls and establish a secure beachhead. By the end of the day of bloody fighting, the Marines held the extreme western tip of the island, as well as a small beachhead in the center of the northern beach. In total, it amounted to less than a quarter of a mile.

The following day, U.S. forces pushed inland toward the airstrip positioned in the island’s center and continued to work to secure the beaches. Marines had the greatest success on the western beach, where naval gunfire enabled the Marines to quickly secure a beachhead. When the Marines began to advance eastward the next day, supported by two borrowed Sherman tanks, Japanese machine gun nests impeded their advance. However, on Nov. 22, continued American pressure from the north and west pushed most of the remaining Japanese defenders into a small area east of the central airstrip. That night, in desperation, the Japanese consolidated for a banzai-style counterattack against the Marines. The American line wavered, and every last reserve, including cooks and administrative staff, was thrown in but the line held.

In the early morning hours of Nov. 23, the Japanese launched a second, third, and then a fourth banzai attack. Again, the Marines fought to hold the line, and again they pushed the Japanese back. These attacks were the last organized Japanese effort to expel the Americans off the island. By then, the only remaining Japanese resistance on Betio consisted of small pockets on the island’s eastern side. The Marines, with support from tanks, aircraft, artillery, and a handful of bulldozers, methodically destroyed these remaining defensive positions. By early afternoon, American lines reached the eastern tip of Betio, and the island was declared secure. Isolated groups of Japanese continued to appear in the weeks following the battle, but except for 147 prisoners—most of them Korean laborers—the entire Japanese garrison was wiped out.

The original plan for Tarawa assumed that tens of thousands of assault troops would be able to quickly overrun the island, but it took four days of heavy fighting that cost the lives of 1,009 Marines with 2,101 wounded, for an island of only a few acres. Most of the Marines were killed during the first day of fighting by enemy artillery or machine gun fire while still in the transport boats or while wading to shore. The U.S. Navy’s primary loss was the escort carrier USS Liscome Bay (CVE-56), which was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine while supporting Galvanic; 646 officers and enlisted personnel were killed. Two submarines, USS Corvina (SS-226) and USS Sculpin (SS-191), were also lost. Out of the Japanese garrison, 4,690 were killed. On Nov. 24, the Marines departed Betio for Hawaii to recuperate until their next assignment. Once they left, U.S. Navy construction battalions, Seabees, began work to improve the island’s airstrip and turn the island into a military base. For a more detailed account of the Battle of Tarawa, read H-Gram 025-1 by NHHC Director Sam Cox on NHHC’s website.

Battleship Maine Launched, Always Remembered

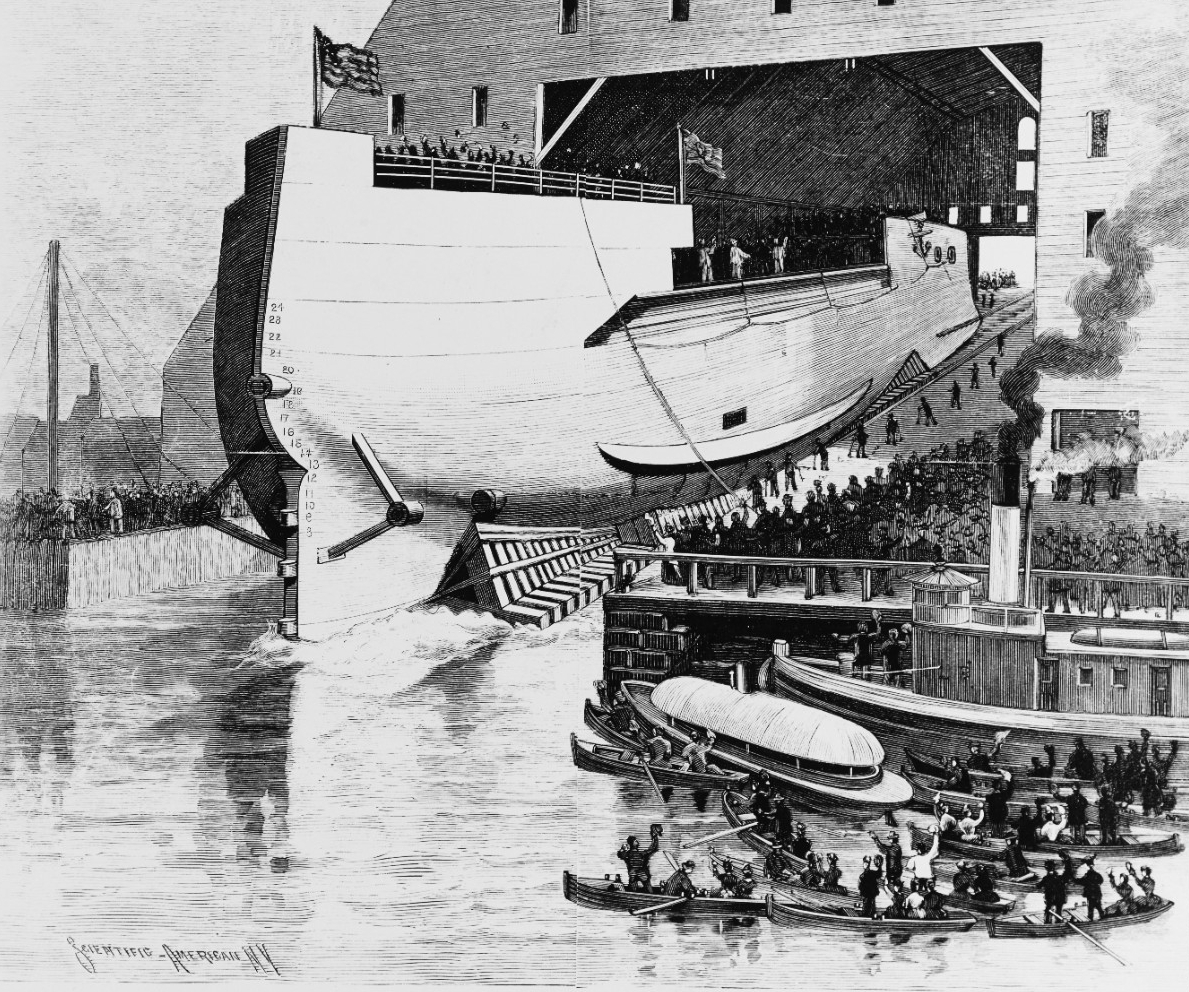

On Nov. 18, 1889, battleship Maine, named for the 23rd state admitted to the Union, was launched at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. More than 20,000 people attended the ceremony that was overseen by Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Tracy. At the time of launch, the ship was the largest ever built in a U.S. Navy shipyard. It took almost five years to construct Maine. As one of the first ships to be built as part of the new “Steel Navy,” it was constructed in partial response to the growth of South American navies, especially the British-built Brazilian armored cruiser Riachuelo, which was considered the most powerful ship in the western hemisphere in the mid-1880s. Steam power, though previously a part of U.S. Navy ship propulsion, was new enough that Maine was initially designed to employ sails and rigging in addition to coal-powered engines. However, the sails were ultimately dropped midway through the design stage. The armor alone required three years due to the difficulties in procuring nickel and steel. Some of Maine’s fittings utilized the latest technology and thus were particularly hard to acquire. For example, the ship needed 400 light fixtures, just over a decade after Thomas Edison had built the first incandescent lightbulb. The ship also needed an enormous number of accoutrements to include side ladders, stowage of torpedoes, ordnance and electrical storerooms, ventilation, voice tubes, magazines, shell rooms, ammunition trolleys and hoists, and much more.

When the ship was finally commissioned as a second-class battleship on Sept. 17, 1895, Capt. Arent S. Crowninshield, a New Yorker and Civil War veteran, took command of the ship. As the Navy’s newest and largest ship, duty on board Maine was considered a prestigious assignment, given to rising naval stars such as Lt. Cmdr. Adolph Marix, the executive officer and the first Jewish graduate of the Naval Academy, and Navigator Lt. George Holman. Chaplain John Chidwick, one of the first Roman Catholic chaplains in the Navy, was also assigned to Maine at its commissioning. Maine was ultimately staffed by 31 officers and 346 Sailors and Marines recruited from across the United States. Although the ship was commissioned and staffed, it still needed a lot of work. It would not be until Nov. 4 when Maine finally left the Brooklyn Navy Yard and anchored at Sandy Hook Bay in New York Harbor later that day. During the next three years, Maine conducted operations mostly off the U.S. eastern seaboard. Capt. Charles D. Sigsbee took command of Maine on April 10, 1897.

During the late 1800s, tensions between Spain and the United States rose out of the attempts by Cubans to liberate their island from Spanish control. The first Cuban insurrection was unsuccessful and ended in 1878. American sympathies were with the revolutionaries, and war with Spain nearly erupted when the filibuster ship Virginius was captured and most of the crew (including many American citizens) were executed. The Cuban revolutionaries continued to plan and raise support in the United States. The second bid for independence by Cuban revolutionaries began in April 1895. The Spanish government reacted by sending Gen. Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau with orders to pacify the island. The “Butcher,” as he became known in the U.S., was determined to deprive the rebels of support by forcibly reconcentrating the civilian population in the troublesome districts to areas near military headquarters. This policy resulted in the starvation and death of more than 100,000 Cubans. Outrage in many sectors of the American public, fueled by stories in the “Yellow Press,” put pressure on Presidents Grover Cleveland and William McKinley to end the fighting in Cuba. American diplomacy, along with the return of the Liberal Party to power in Spain, led to the recall of the Spanish general. However, beset by political divisions at home, the new Spanish government was too weak to enact meaningful reforms in Cuba. Limited autonomy was promised late in 1897, but the U.S. government was mistrustful, and the revolutionaries refused to accept anything short of total independence.

When pro-Valeriano Weyler forces in Havana instigated riots in January 1898, Washington became greatly concerned for the safety of Americans in the country. The administration believed that some means of protecting U.S. citizens should be put in place. On Jan. 24, President McKinley sent Maine from Key West, Florida, to Havana, after clearing the visit with a reluctant government in Madrid. The battleship arrived the next day. Spanish authorities in Havana were wary of American intentions, but they afforded Sigsbee and the officers of Maine every courtesy. In order to avoid the possibility of trouble, Maine’s commanding officer did not allow his enlisted men to go on shore. Sigsbee and the consul at Havana, Fitzhugh Lee, reported that the Navy’s presence appeared to have a calming effect on the situation, and both recommended that the Navy Department send another battleship to Havana when it came time to relieve Maine.

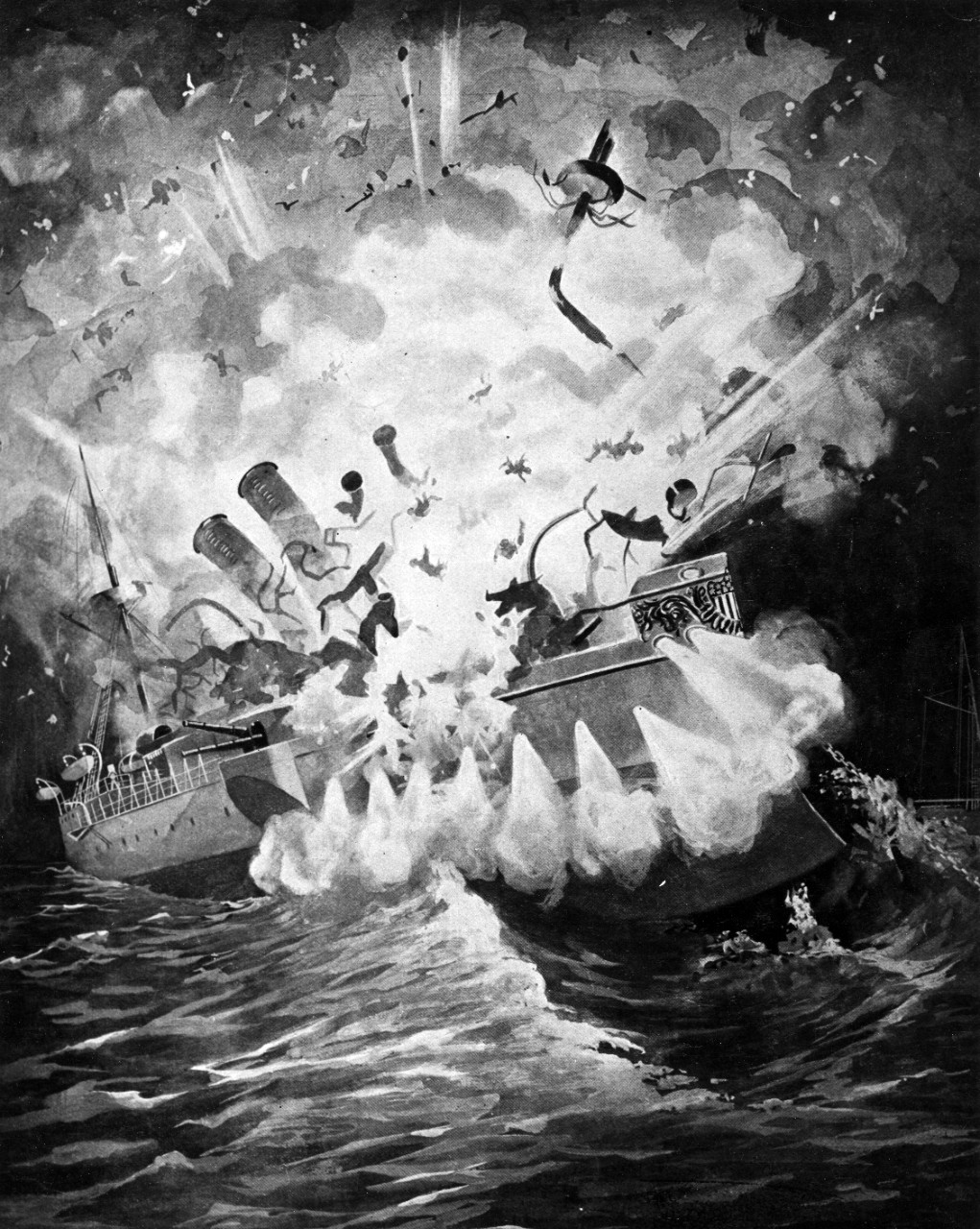

At 9:40 p.m. on Feb. 15, a massive explosion on board Maine rocked the stillness of Havana Harbor. Later investigations revealed that more than five tons of powder charges for the vessel’s six- and ten-inch guns ignited, virtually obliterating the forward third of the ship. The remaining wreckage rapidly settled to the bottom of the harbor. Most of Maine's crew were sleeping or resting in the enlisted quarters in the forward part of the ship when the explosion occurred. Two hundred and sixty-six men lost their lives because of the disaster—260 died in the explosion or shortly thereafter, and six more died later from injuries. Sigsbee and most of the officers survived because their quarters were in the aft portion of the ship. Spanish officials and the crew of the civilian steamer City of Washington acted quickly in rescuing survivors and caring for the wounded. The attitude and actions of the Spanish alleviated initial suspicions that hostile action caused the explosion and led Sigsbee to include at the bottom of his initial telegram that “public opinion should be suspended until further report.” The U.S. Navy Department immediately formed a board of inquiry to determine the reason for Maine’s destruction. The inquiry, conducted in Havana, lasted four weeks. The condition of the submerged wreck and the lack of technical expertise prevented the board from being as thorough as later investigations. In the end, they concluded that a mine had detonated under the ship. The board did not attempt to fix blame for the placement of the device.

When the Navy’s verdict was announced, the American public reacted with predictable outrage. Fed by inflammatory articles by the American press that blamed Spain for the disaster, the public was coerced to place guilt on the Spanish government. “Remember the Maine!” became the American battle cry. Although he continued to press for a diplomatic solution to the Cuban problem, President McKinley accelerated military preparations. The Spanish position on Cuban independence hardened, and McKinley asked Congress on April 11 for permission to intervene. On April 21, the president ordered the Navy to begin a blockade of Cuba, and Spain followed with a declaration of war two days later. Congress responded with a formal declaration of war on April 25, made retroactive to the start of the blockade. The Spanish-American War had begun.

In 1911, the Navy Department ordered a second board of inquiry after Congress voted funds for the removal of the wreck of Maine from Havana Harbor. U.S. Army engineers built a cofferdam around the sunken battleship, thus exposing it and giving naval investigators an opportunity to examine and photograph the wreckage in detail. Finding the bottom hull plates in the area of the reserve six-inch magazine bent inward and back, the 1911 board concluded that a mine had detonated under the magazine, causing the explosion that destroyed the ship. Technical experts at the time disagreed with the findings, believing that spontaneous combustion of coal in the bunker adjacent to the reserve six-inch magazine was the most likely cause of the explosion on board the ship. In 1976, Adm. Hyman G. Rickover published his book How the Battleship Maine Was Destroyed. Rickover became interested in the disaster and wondered if the application of modern scientific knowledge could determine the cause. He called on two experts on explosions and their effects on ship hulls. Using documentation gathered from the two official inquiries, as well as information on the construction and ammunition of Maine, the experts concluded that the damage caused to the ship was inconsistent with the external explosion of a mine. The most likely cause, they speculated, was spontaneous combustion of coal in the bunker next to the magazine.

Some historians have disputed the findings in Rickover’s book, maintaining that failure to detect spontaneous combustion in the coalbunker was highly unlikely. Yet, evidence of a mine remains thin, and such theories are based primarily on conjecture. Despite the best efforts of experts and historians in investigating this complex and technical subject, a definitive explanation for the sinking of Maine remains elusive.

JFK Witnessed Launch of Polaris A-2 Missile

On Nov. 16, 1963, President John F. Kennedy, on board USS Observation Island (EAG-154) off Cape Canaveral, Florida, witnessed the launch of a Polaris A-2 missile by Lafayette-class submarine USS Andrew Jackson (SSBN-619). The president congratulated Cmdr. James B. Wilson and his Gold crew for “impressive teamwork.” The launch was just six days before Kennedy’s assassination on Nov. 22, 1963. Previously, Andrew Jackson, during shakedown training on Oct. 1 and 11, 1963, successfully launched A-2 Polaris missiles. On Oct. 26, it sent A-3X Polaris missiles into space in the first submerged launch of its type. It repeated the feat on Nov. 11. From 1963–67, the Navy built 19 Lafayette and James Madison–class and 12 Benjamin Franklin-class ballistic-missile submarines. Later, all of them were converted to Poseidon missile capability. The Poseidon (C-3) weighed nearly twice as much as the Polaris A-3, but carried four times the payload while increasing accuracy to a circular error probability of a quarter mile. Moreover, it was capable of a longer range and could incorporate multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicles, or MIRV technology, meaning one missile could deliver multiple warheads to multiple targets.

The goal of strategic deterrence is to discourage adversaries from launching a nuclear attack. The U.S. Navy’s submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) play a key role in the strategic deterrence mission by providing the U.S. with second-strike capability. Hidden at sea on nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), SLBMs can survive an initial nuclear attack and launch missiles in retaliation. This guaranteed retaliation is a powerful deterrent to opponents considering a first strike. In fact, the Navy’s SSBNs have long been recognized by the Department of Defense as the most survivable leg of the United States’ nuclear triad, also composed of strategic bombers and land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles.

After the successor to Polaris, Poseidon, was introduced in March 1971, the introduction of two new SLBMs with considerably longer ranges and payloads—the Trident I (C4) in 1979 and Trident II (D5) in 1990—transitioned the Navy through the end of the Cold War and into the era of modern strategic deterrence. Eighteen Ohio-class SSBNs, commissioned between 1981 and 1997, replaced the original 41 for Freedom SSBNs and became the largest submarines built by the U.S. Navy. However, in the 2000s the Navy converted the first four Ohio-class SSBNs to guided missile submarines (SSGNs) after the 1994 Nuclear Posture Review recommended the U.S. only needed 14 SSBNs to meet strategic deterrence needs. In addition, the DoD has permanently reduced the Ohio-class submarines’ SLBM capacity from 24 SLBMs to 20 in compliance with U.S.-Russia strategic nuclear arms control limits.

As adversaries expand their nuclear capabilities, the Navy is now prioritizing the Columbia-class program: a minimum of 12 new SSBNs to replace the aging Ohio-class SSBNs. Columbia (SSBN-826), the first Columbia-class SSBN, was laid down on Oct. 1, 2020, and is expected to become operational in 2031.

Today in Naval History—Naval Aviation Was Born

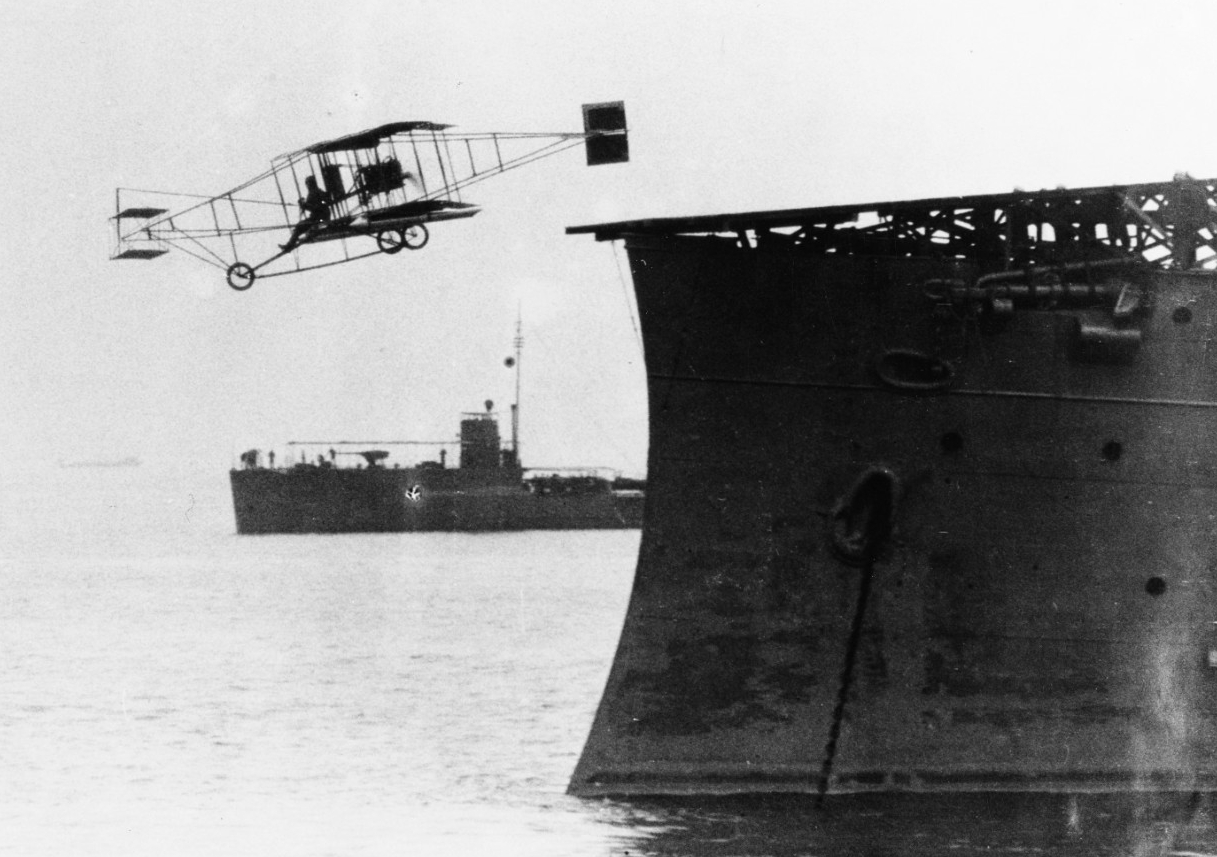

On Nov. 14, 1910, light cruiser USS Birmingham (CL-2) was readied at Hampton Roads, Virginia, with a slanted wooden platform, approximately 80 feet long, built onto the bow. Civilian stunt pilot Eugene Ely’s 50-hp Curtiss plane, equipped with floats under the wings, was hoisted aboard the ship and moved offshore. Despite light rain and fog, Ely elected to continue with the historic flight. As he left the platform, the plane settled slowly and touched the water, but it rose again and landed about two and a half miles away on Willoughby Spit. During the flight, the aircraft sustained slight splinter damage to the propeller tips.

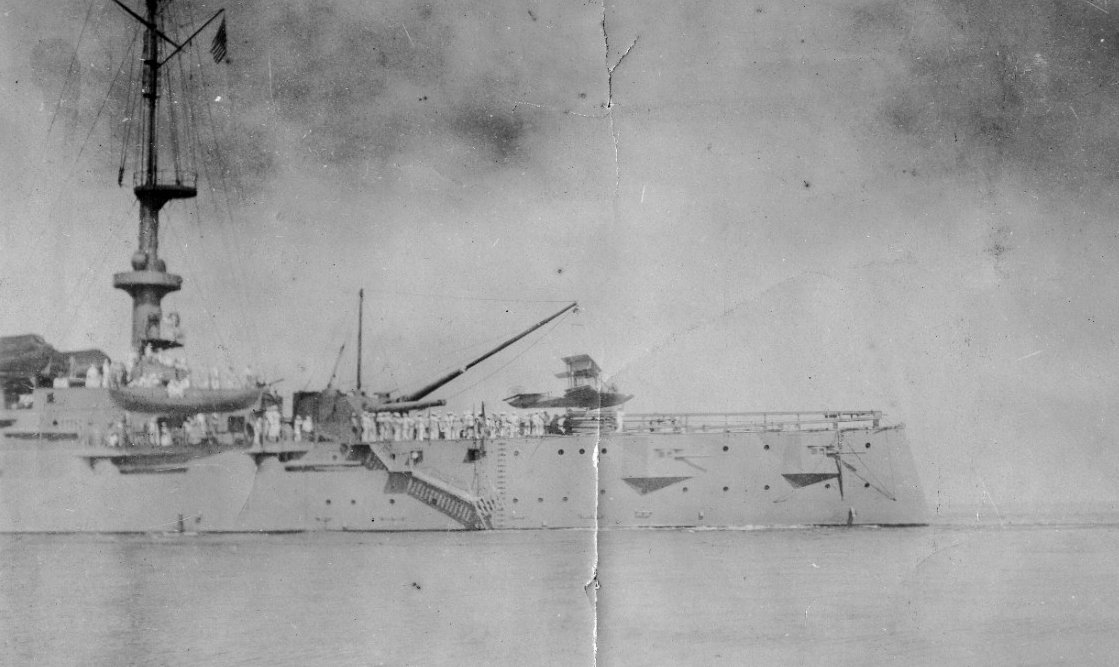

Although taking off from a ship was a tremendous feat, landing on one was quite another. Regardless of the somewhat harrowing flight off Birmingham, Ely was ready to give it a shot. With Ely and the Curtiss team scheduled to fly in San Francisco in January 1911, Navy Capt. Washington I. Chambers made arrangements for the attempt on the West Coast. Armored cruiser USS Pennsylvania (ACR-4) was prepared and anchored in San Francisco Bay. This time a longer platform was put in place, 120 feet, along with ropes and sandbags stretched across the deck to serve as a crude arresting system for landing. There was also a canvas awning at the end of the makeshift runway to catch the airplane if the ropes and sandbags did not hold. With longer wings and hooks on the landing gear and Ely wearing a padded football helmet and bicycle tubes around his body, all was ready on the morning of Jan. 18. Crowds were lined up on shore and boats collected in the harbor to witness the daring flight. At 11 a.m., Ely took off from nearby Tanforan Race Track and headed towards Pennsylvania. To the delight of the crowd, Ely made a safe landing and the arresting equipment worked perfectly. After lunch with the ship’s captain and a few photographs, the platform was cleared, and Pennsylvania was pointed into the wind. Ely took off, flew by the cheering crowd, and safely landed back at Tanforan. Naval aviation was born!

The U.S. Navy’s official interest in airplanes emerged as early as 1898. That year, the Navy assigned officers to sit on an interservice board to investigate the military possibilities of Samuel P. Langley’s flying machine. In subsequent years, naval observers attended air meets in the United States and abroad, and public demonstrations staged by Orville and Wilbur Wright in 1908 and 1909. These naval observers became enthusiastic about the potential of airplanes as fleet scouts, and by 1909 many naval officers, including a bureau chief, urged the purchase of aircraft. The next year, the Navy made a place for aviation in its organizational structure when Chambers was designated as the officer to whom all aviation matters were to be referred. Before the Navy had either planes or pilots, he arranged a series of tests in which civilian aircraft designer Glenn H. Curtiss and Ely dramatized the airplane’s capability for shipboard operations and showed the world and a skeptical fleet that aviation could go to sea. Early in 1911, the first naval officer reported for flight training. By mid-year, the Navy appropriated the first funds, purchased the first aircraft, qualified the initial pilot, and selected the site of the first aviation camp.

Recognizing the need for science, Chambers collected the writings and scientific papers of leaders in the new field, pushed for a national aerodynamics laboratory, and encouraged naval constructors to work on aerodynamic and hydrodynamic problems. The Navy built a wind tunnel, and the nation established the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. A board under Chambers’ leadership conducted the first real study of what was needed in aviation and included in its recommendations the establishment of a ground and flight training center at Pensacola, Florida, the expansion of research, and the assignment of an airplane to every major combatant ship of the Navy.

Naval aviation’s progress in these early years included setting an endurance record of six hours in the air; the first successful catapult launch of an airplane from a ship; exercises with the fleet during winter maneuvers at Naval Station Guantánamo Bay, Cuba; and combat sorties at Veracruz, Mexico. In 1914, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels announced that the Navy had reached the point “where aircraft must form a large part of our naval forces for offensive and defensive operations.” For more on naval aviation, visit NHHC’s website.