Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On Aug. 23, 1819, Oliver Hazard Perry died of yellow fever while on board schooner Nonsuch. Considered a hero of the Battle of Lake Erie during the War of 1812, Perry was on a diplomatic mission to negotiate an antipiracy agreement with Venezuelan President Simon Bolivar. After he came to a successful agreement with the Latin American government on Aug. 11, his ship set sail, but during the talks, 20 of the crew came down with yellow fever and five died. Perry had hoped that he had escaped the fever and was anxious for a quick passage to the fresh breezes of Port of Spain, Trinidad. However, he did not escape the disease. In the early morning of Aug. 17, Perry woke with chills and a fever. Always susceptible to illness, Perry’s condition rapidly deteriorated. Although the crew frantically pushed themselves and their vessel in an effort to reach Port of Spain, their efforts fell short by only a few miles. He was just 34 years old.

Born on Aug. 20, 1785, at South Kingstown, near the village of Wakefield, Rhode Island, Perry was the oldest of five brothers and three sisters. At the age of 13, the strong-willed youth decided on a naval career. Before the U.S. Naval Academy was founded, an aspiring naval officer was required to obtain a midshipman’s warrant from the Secretary of the Navy. It was much easier to obtain the warrant if the candidate possessed “influence.” During the early months of 1799, frigate General Greene was in the process of fitting out and her captain, Perry’s father Christopher, recommended his son for one of the coveted midshipman appointments. Over the course of the next six years, Perry participated in the Quasi-War with France and the Tripolitan War against the Barbary pirates. He also served on memorable ships such as Adams, Constellation, Nautilus, Essex, and Constitution. In April 1809, he received his first seagoing command, 14-gun schooner Revenge.

During the summer and winter of 1809, Revenge served as part of Commodore John Rodgers’ New York flotilla. In the spring of 1810, Perry’s ship was ordered to the Washington Navy Yard to prepare for duty in southern waters. In June of that year, while sailing to Charleston, South Carolina, Revenge lost several spars and suffered considerable damage while battling heavy seas. To make matters worse, Perry was plagued by health issues. His fragile health also made him very susceptible to the extreme heat and humidity of southern summers. Perry’s unfortunate tour of duty on Revenge ended on Jan. 8, 1811, when the ship, in heavy fog, struck a reef and sank. A subsequent court-martial exonerated Perry. The findings of the court-martial blamed the pilot of ship, who had assured Perry that he would have no problem navigating through the fog.

After commanding Revenge, Perry got married and spent some time as an unassigned naval officer. In May 1812, the threat of war with Great Britain spurred him to the sea again. Unfortunately for Perry, he was assigned to command a squadron of tiny gunboats at Newport, Rhode Island, which angered him. Dissatisfied with the assignment, Perry petitioned the Navy for a posting at sea. After several failed attempts, he petitioned his friend, Isaac Chauncey, who then commanded naval operations on the Great Lakes. His timing was perfect since Chauncey was in need of an experienced naval officer for the flotilla that was under construction at Lake Erie. Finally, on Feb. 8, 1813, Perry received orders to report to Chauncey. By early autumn, the assembly of the flotilla was complete and it was ready to battle the enemy.

During the Battle of Lake Erie that took place on Sept. 10, 1813, Perry’s fleet of nine ships engaged six enemy warships under the command of British Capt. Robert Heriot Barclay. After Perry’s flagship, Lawrence, suffered heavy casualties and was reduced to a defenseless wreck, he transferred to a sister ship, Niagara, and sailed directly into the British line. Within 15 minutes, while firing broadsides, he forced all of Barclay’s ships to surrender. The destruction of the British squadron on Lake Erie reversed the course of the British campaign and forced them to abandon Detroit. Perry’s victory raised him to a position of national prominence and earned him the rank of captain. During the early hours of the engagement with the British squadron, Perry famously flew the “Don’t Give up the Ship” battle ensign, which is displayed at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

Japan Formally Surrendered

On Sept. 2, 1945, more than two weeks after Japan agreed to surrender unconditionally, the instrument of surrender was signed by representatives of the Allied and Japanese governments on board battleship USS Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay. It marked the end of World War II.

By the summer of 1945, the defeat of Japan was a foregone conclusion. It was more of a matter of how the Allies would bring the Japanese to the table. Their navy and air force were essentially destroyed and intensive bombing of Japanese cities left the country and its economy devastated. Near the end of June, the Americans’ successful capture of the Japanese island of Okinawa put the Allies within distance of Japan to launch an invasion. Code-named “Operation Olympic,” was scheduled for November 1945 under Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s command. However, the invasion was assured to be the bloodiest amphibious assault of all time. Some estimated it could be 10 times as costly in casualties as the Normandy invasion.

On July 16, a new option became available when the United States secretly detonated the world’s first atomic bomb in the New Mexico desert. Ten days later, the Allies issued the Potsdam Declaration, demanding the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces. On July 28, Japanese Prime Minister Kantaro Suzuki responded that his government was “paying no attention.” President Harry S. Truman decided to use the weapon against Japan rather than lose more American lives in an invasion. On Aug. 6, B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, an industrial center in western Honshu. An estimated 90,000 to 120,000 Japanese were killed. Despite recognizing the weapon’s destructive potential, the Japanese leadership estimated that the United States had only one or two additional bombs ready and decided to continue hostilities.

On Aug. 8, Japan’s situation got much worse when Russia declared war and Japanese-held Manchuria was invaded the following day. On the same day, a second atomic bomb was dropped on the port city of Nagasaki, in Kyushu. An estimated 129,000 to 226,000 Japanese were killed. Just before midnight on Aug. 9, Japanese Emperor Hirohito convened his supreme war council. After a long debate, he backed the proposal by Prime Minister Suzuki in which Japan would surrender “with the understanding that the declaration does not compromise any demand that prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as the sovereign ruler.” The council obeyed the emperor’s ruling, and on Aug. 10, relayed a message to the United States that they would accept the terms of peace. On Aug. 14, Hirohito’s surrender announcement to the Japanese nation was recorded. Despite an attempted last-minute coup by radical militarists, the message was broadcasted. Japan agreed to surrender unconditionally and World War II was finally over.

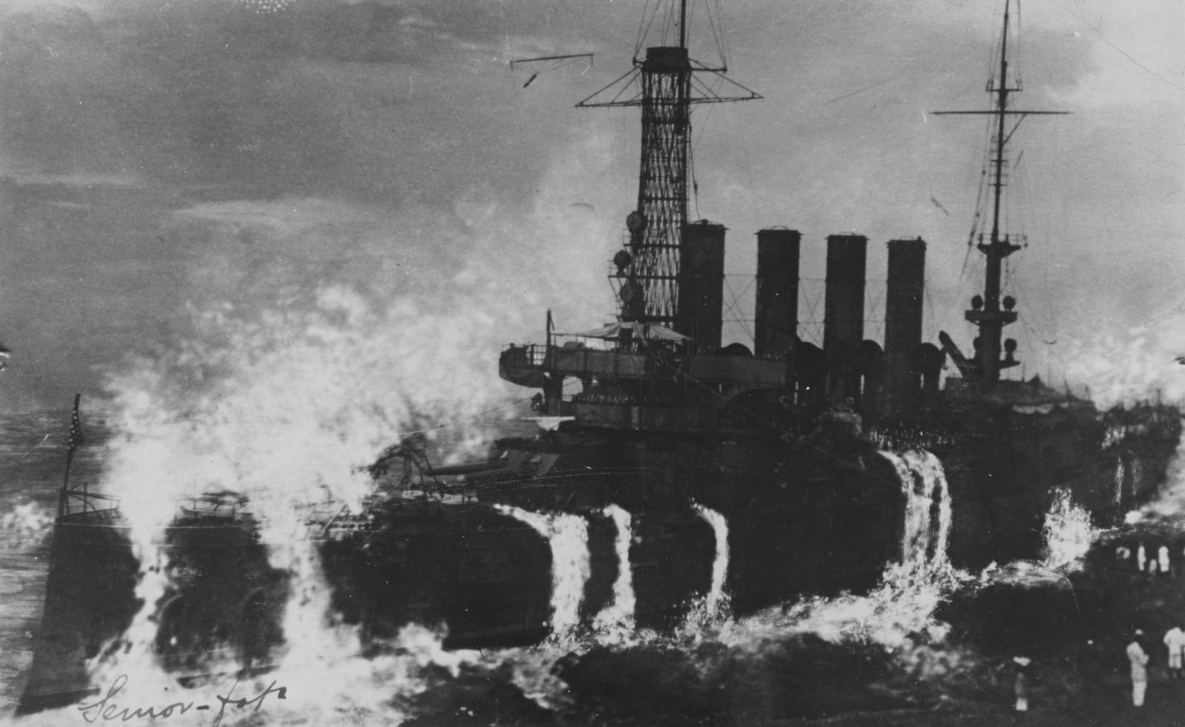

Memphis Driven Ashore

On the afternoon of Aug. 29, 1916, armored cruiser Memphis (Armored Cruiser No. 10) and gunboat Castine were at anchor at Santa Domingo harbor, Dominican Republic, when a series of tsunami type waves inundated the harbor, driving Memphis ashore and almost wrecking Castine. The waves were so steep, reportedly 75 feet high, that they flowed over the cruiser, including the bridge and even the stacks, and repeatedly battered the warship into the harbor bottom. The massive waves swamped Memphis as Sailors in the engine rooms and fire rooms tried in vain to power up the steam engines to get the ship underway. Castine survived the storm by steaming out to sea. In less than two hours, Memphis was wrecked. Above the waterline, the ship didn’t appear to be damaged, but below the surface of the water the ship’s hull was crushed, conforming to the rocks and coral on which she lay on the shore of Santo Domingo. The lower decks were flooded almost to the waterline, leaving Memphis stranded in shallow water.

The crew of Memphis heroically battled to save the ship, but the sea’s abrupt destructive action proved to be too much. Along with the loss of the ship, 43 Sailors lost their lives and many more were injured. Three Sailors received the Medal of Honor for their heroic actions on that day—Commander Claud Ashton Jones, Chief Machinist’s Mate George William Rud (posthumously), and Machinist Charles H. Willey.

Naval and civilian experts soon carefully examined Memphis and determined that while it would have been possible to salvage the wreck, they considered it impracticable because of the cost, and because delivering Memphis to a port with the facilities capable of repairing her would prove difficult and dangerous. The salvage, if successful, and repairs, if undertaken, would have taken two to three years and cost close to the value of the ship. In addition, the aging vessel was of a type no longer constructed by any naval power. All articles of a portable nature, whose value was commensurate with the cost of removal, were therefore recovered, and Memphis was stricken from the Navy list on Dec. 17, 1917. The wreck of Memphis remained on the shore of Santo Domingo for 21 years until sufficient ship-breaking capability became available to salvage the ship.

The U.S. Navy conducted three inquires to investigate the tragedy. All three were conducted in the first weeks of September 1916. Among the significant findings was thatthe heavy rolling of Memphis had caused water spray to enter the stacks, hampering attempts to power up the engines to get underway. Moreover,there had been a tropical disturbance, which passed south of Santo Domingo during the night before the tragedy. The disturbance produced no wind or other markers of severe weather, but “produced the heavy swells, which coming in from the deep water to the shallow water of Santo Domingo City anchorage, caused heavy seas that eventually dragged and wrecked Memphis.” Finally,the commanding officer of the ship, Capt. Edward L. Beach, should have given the order to raise steam to power the engines earlier, anchored Memphis in a safer anchorage, and taken steps to save the ship and recognize the emergency sooner. Beach was subsequently convicted by cour-t martial of “not having enough steam available to get under way on short notice;” however, the charge was widely regarded as unwarranted.

Memphis began her service to the Navy as armored cruiser Tennessee and was commissioned at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on June 20, 1903. On her maiden cruise, she served as escort for Louisiana (Battleship No. 19), which had embarked President Theodore Roosevelt for a cruise to inspect the status of work on the Panama Canal. After both ships returned, and after repairs, Tennessee made way for the Jamestown Exposition, held off Sewell’s Point in Norfolk, Virginia, to commemorate the tricentennial of the founding of the first English settlement in America. After several cruises in the Atlantic, Tennessee was reassigned to the Pacific Fleet in late 1907. Tennessee operated in Pacific waters for several years before she was reassigned again as flagship for the Fifth Division of the Atlantic Fleet. Tennessee operated in the Atlantic until joining the Reserve Fleet in Philadelphia on Oct. 23, 1913, where she remained inactive until the outbreak of World War I. Over the course of the “Great War,” Tennessee, among other missions, was instrumental in evacuating thousands of refugees from Jaffa, Palestine, and helped quell ongoing violence in Haiti.

After the Naval Act of 1916 was passed, President Woodrow Wilson’s request to “build a Navy equal to any other in the world,” included ten additional battleships, one of which (Battleship No. 43) was slated to be named Tennessee. Consequently, on May 25, Tennessee was renamed Memphis, honoring the city in Tennessee, so that the name of the state could be reassigned to one of the new ships. About a month later, Beach took command of Memphis, and was underway for the West Indies, arriving at Santa Domingo on July 23 for a peacekeeping patrol off the rebellion-torn republic.

End of an Era: Last Navy Airship Flight

On Aug. 31, 1962, the last flight of a Navy airship was made at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey. The Secretary of the Navy had announced about a year earlier that he was going to terminate the Navy’s lighter-than-air program. The Navy had launched the program when it awarded its first contract for an airship, DN-1, to the Connecticut Aircraft Company in June 1915. (The designation stems from D for dirigible, N for non-rigid and “1” as the Navy’s first airship.) During construction of DN-1, the Navy authorized construction of a hangar to house the new airship, which was completed in early 1916. DN-1 arrived in Pensacola, Florida, in December 1916, but was not ready for flight until April 1917. Once test flights began, multiple problems were revealed. The airship was severely damaged during one of the test flights and it was never repaired.

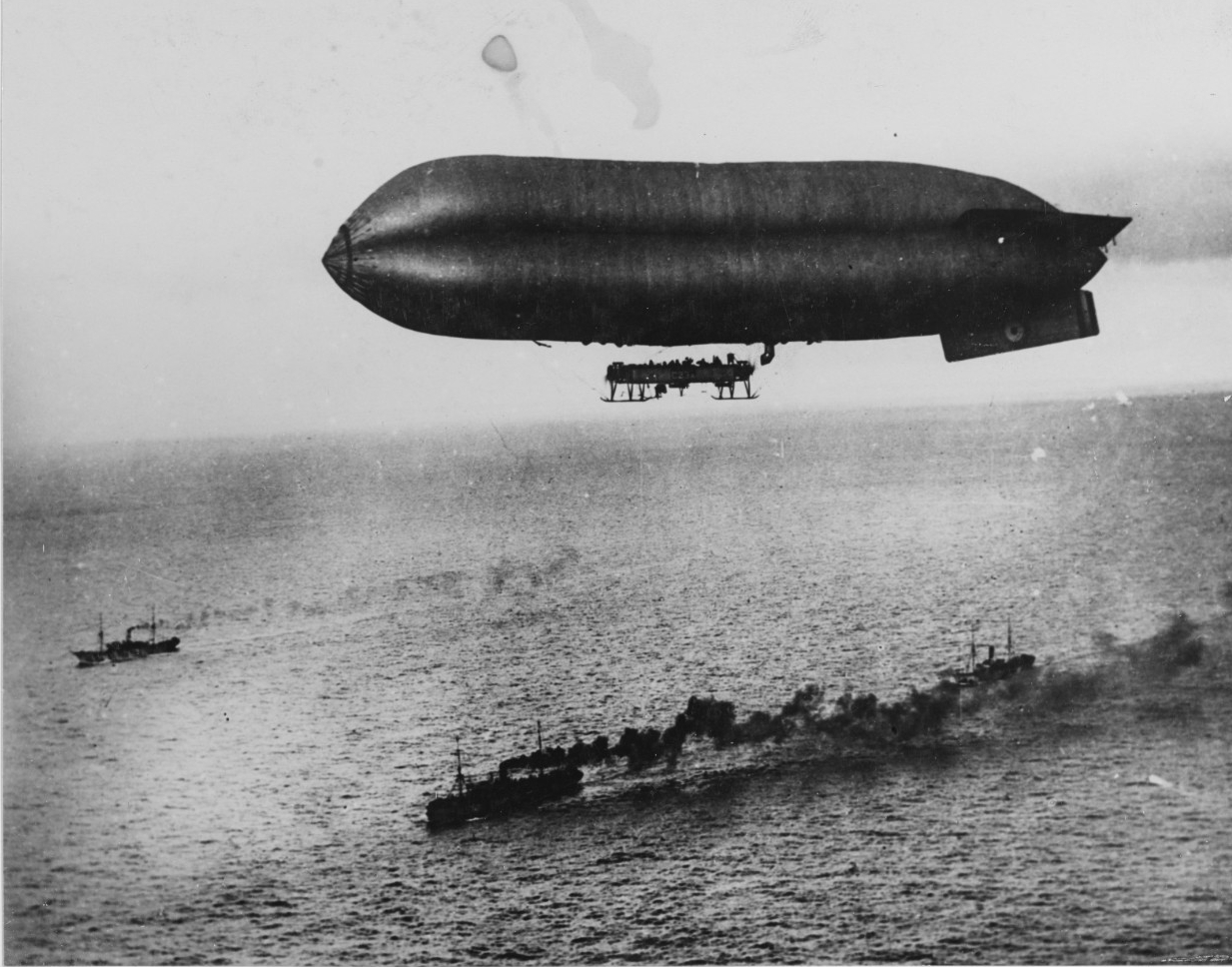

Even before DN-1 was built, studies were ongoing at the Bureau of Construction and Repair for a future class of dirigibles. In April 1916, the General Board endorsed the development of zeppelins and other mobile lighter-than-air craft. At Akron, Ohio, the Navy’s program tested non-rigid airships, free balloons, and kite balloons. During testing, the balloons were found to be an easy target for enemy aircraft and restricted maneuverability when moored to a ship. During World War I, airships and kite balloons were used in conjunction with seaplanes and flying boats to help protect shipping. They were also used to detect submarines and warn vessels of mines. Most of the airship patrols were carried out off the U.S. East Coast and in European waters, where they were deemed successful because they were a deterrent to German submarines.

After World War I was over, the development of non-rigid airships became more advanced as new capabilities were developed. The Navy contracted Goodyear to build airships and hangers were built to accommodate them. The airship Shenandoah (ZR-1) was the first rigid airship to be inflated with helium and the first to fly across the United States. On Sept. 3 1925, while flying over Ohio, Shenandoah ran into a severe storm that broke the airship in two, killing about half the crew. The most successful airship of the time was Los Angeles (ZR-3). The airship had been built by Germany and was given to the United States as compensation for two U.S. airships that were lost during the war. Los Angeles was in operation more than seven years and made more than 330 flights.

Probably the most prolific period in the Navy’s construction of rigid airships was during the era of Akron (ZRS-4) and Macon (ZRS-5). They were viewed as an improvement from the Shenandoah design having the ability to house and carry other aircraft, although they ended up being the first and last flying carriers. Akron was lost in 1933 off the coast of New Jersey during a storm that killed 73 crewmembers and Macon was lost off the Santa Barbara Islands off California, killing 83.

During World War II, there were five different airship classes/types in the Navy’s inventory. Airship operations and their expansion were unprecedented. The airship fleet conducted operations in the Pacific, Mediterranean, the north Atlantic, and south Atlantic. When the war was over and the military drew down, the Navy still retained two squadrons that conducted mostly training, search and rescue, observation, and photography missions.