Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On May 2, 1945, Hospital Apprentice First Class Robert E. Bush was serving with a rifle company in 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division, when it was met with heavy enemy resistance during the Battle of Okinawa. While the company was on the offensive, a Marine officer was seriously wounded in a fire-swept location. Bush, who had been assisting other wounded Marines, rushed to the officer’s exposed position and administered plasma. As the Japanese counterattacked, he courageously remained with the injured Marine, firing back with one hand while holding a plasma bottle in the other. Despite suffering several serious injuries, including the loss of his right eye, Bush continued to provide aid until his patient was evacuated. After the battle, Bush was treated for his wounds on board USS Relief (AH-1) and at several military hospitals. During one of his extended hospital stays in Hawaii, he continuously played ping pong to regain hand-eye coordination. He was ultimately honorably discharged from the Navy at Naval Hospital Oakland, California, on July 26, 1945. After his discharge, Bush and his new wife, Wanda, traveled on their honeymoon to Washington, DC, for the formal award presentation of the Medal of Honor. It was presented to Bush by President Harry S. Truman at a White House ceremony two days before he turned 19. At just 18 years old, he was the youngest Sailor to receive the Medal of Honor during World War II.

Born a logger’s son in Tacoma, Washington, Bush’s parents divorced when he was four years old, and he was raised in the coastal town of Raymond, Washington. He lived with his mother, a nurse, in basement rooms of the hospital where she worked. On Jan. 5, 1944, at 17, he dropped out of high school (he completed his high school education after the war) and enlisted as a seaman apprentice in the U.S. Naval Reserve at Navy Recruiting Station Seattle. Bush trained at Naval Training Station Farragut, Idaho, and at the Naval Hospital Corps School, also in Farragut. He served at Naval Hospital Seattle before further training and service with the training detachment in the Field Medical School Battalion, Fleet Marine Force Training Center, Camp Pendleton, California. During his training, he was promoted to seaman second class, and then to hospital apprentice second class. On Feb. 10, 1945, Bush transferred to the 1st Marine Division. He was advanced to hospital apprentice first class a few weeks later.

After the war, Bush became a successful businessman, buying a small lumber company in South Bend, Washington, for several hundred dollars. With a partner, he turned it into a multi-million-dollar enterprise over the next 50 years. He also was involved in several building material businesses before retiring in the mid-1980s. He served as president of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society from October 1971 to November 1973 as well. Bush passed away at an assisted living facility in Tumwater, Washington, on Nov. 8, 2005, due to kidney cancer. He was 79. His beloved wife had predeceased him in 1999.

In addition to the Medal of Honor, Bush’s awards included the Purple Heart, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal. Also, Branch Medical Clinic Bush on Okinawa and the Robert E. Bush Naval Hospital at Twentynine Palms, California, were named in his honor in July 1988 and May 2000, respectively.

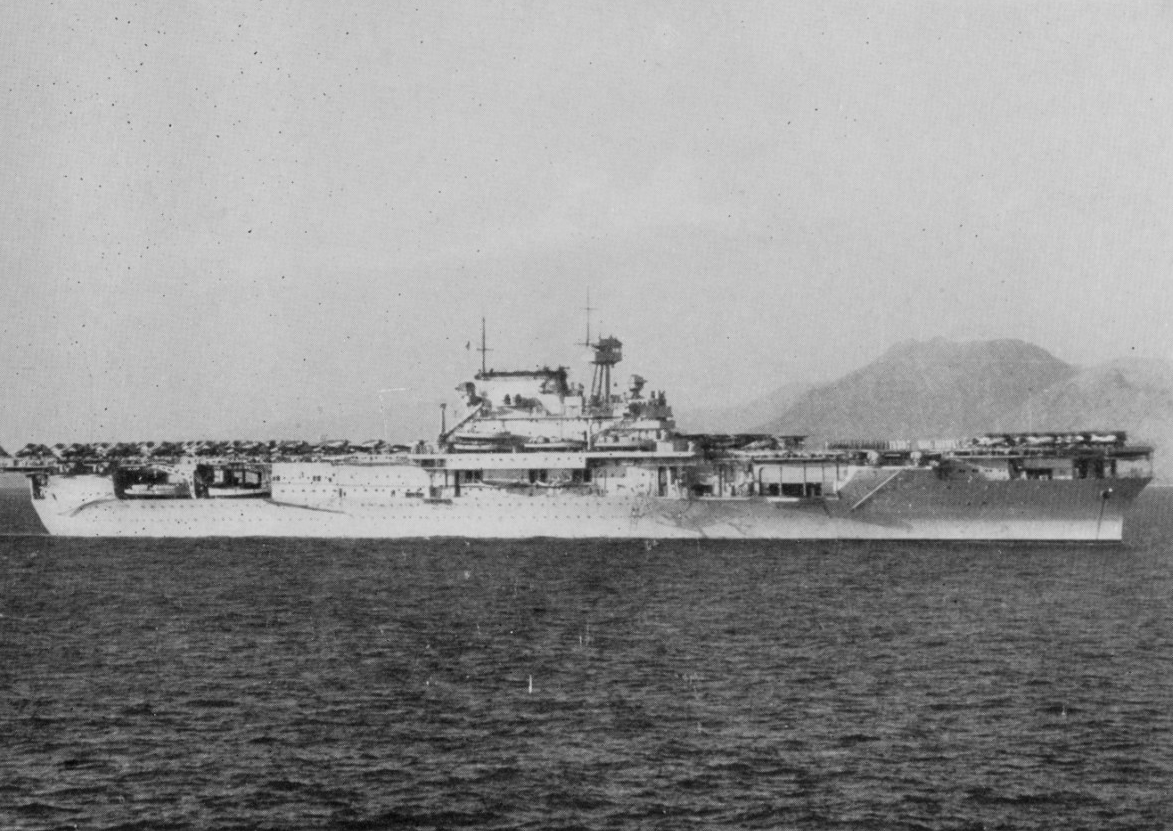

Enterprise Commissioned

On May 12, 1938, USS Enterprise (CV-6) was commissioned at Naval Operating Base Norfolk, Virginia. The ship was the seventh U.S. Navy vessel named Enterprise. Then–Rear Adm. Ernest J. King, who was chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics at the time, recommended the name Enterprise to Secretary of the Navy Claude A. Swanson. “This is one of the most famous names of the Navy through its association in the French Revolutionary and Tripolitan wars,” said King. “It dates back to the Revolutionary War, when it was borne by one of [Benedict] Arnold’s vessels on Lake Champlain.” Enterprise was built under the terms of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, which called for two aircraft carriers to be constructed. The other carrier was USS Yorktown (CV-5).

At the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Enterprise was out at sea about 200 miles west of Oahu. The carrier would go on to become the most decorated warship of World War II, earning 20 battle stars—three more than any other ship. In addition, Enterprise was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation and the Navy Unit Commendation, becoming the only carrier to receive both awards for service in World War II. In addition, on Nov. 23, 1945, Enterprise was awarded the British Admiralty Pennant, making it the only ship awarded this prestigious decoration outside of the British Royal Navy. Some of “Big E’s” most notable engagements were the battles of Eastern Solomons, Santa Cruz Islands, Guadalcanal, Midway, Leyte Gulf, Philippine Sea, and Okinawa. Of the more than 20 major actions of the Pacific War, Enterprise engaged in all but two. Its planes and guns downed 911 enemy planes; its bombers sank 71 ships and damaged or destroyed 192 more.

After the war, the story of Enterprise became public knowledge, and the ship’s name was emblazoned across newspaper headlines throughout the country. On Oct. 17, 1945, Enterprise rejoined the fleet in New York Harbor for Navy Day celebrations on Oct. 27. Moored to Pier 26 on the Hudson River, it welcomed more than a quarter million visitors and rendered passing honors to President Harry S. Truman when he inspected the ships at anchor. That night, Night Air Group 55 flew in formation to salute the valiant ship.

On its last active missions, Enterprise took part in multiple Operation Magic Carpet voyages, reuniting thousands of Sailors, Marines, and Soldiers with their families. It was moored at Bayonne, New Jersey, on Jan. 18, 1946, and would never steam under its own power again. Enterprise was decommissioned on Feb. 17, 1947.

Nearly 1,400 veterans who had served onboard the carrier formed the Enterprise Association to save the ship. Multiple flag officers supported the project, and Fleet Adm. William F. Halsey led the association for a while. The group developed a plan to preserve Enterprise and move it to Washington, DC. Public Law 85-218, passed by the 85th Congress on Aug. 29, 1957, authorized its establishment as a national memorial. National Park Service officials indicated that they would be willing to provide a berth, but only if they could overcome logistic and engineering issues, which hinged upon the association raising enough money to support the project. At one point, Superintendent of National Capital Parks Edward J. Kelly announced that three problems impacted the development of the project. “Number one is parking,” Kelly explained. “Secondly, the ship would have to be towed up the channel, but its draft precludes most berth options without extensive dredging from the channel to shore. Finally, workers would have to strengthen seawalls extensively, since the dredging would have undermined the barriers. Engineers can work it out,” Kelly concluded, “but it will be expensive.” In the end, the money issue doomed the project, as it would have cost an estimated $1 million (estimated at more than $10 million today) to repair the ship, construct a suitable berth, and tow it to Washington. Ultimately, Enterprise was stricken from the List of Naval Vessels on Oct. 2, 1956, and was subsequently sold for scrap. However, parts of the ship were saved. One of the ship’s anchors is on display at Leutze Park on the Washington Navy Yard, and its stern plate is on display in River Vale, New Jersey. In addition, Gene Roddenberry, creator of the American science fiction television series Star Trek, named the fictional starship in honor of CV-6.

War Declared on Mexico

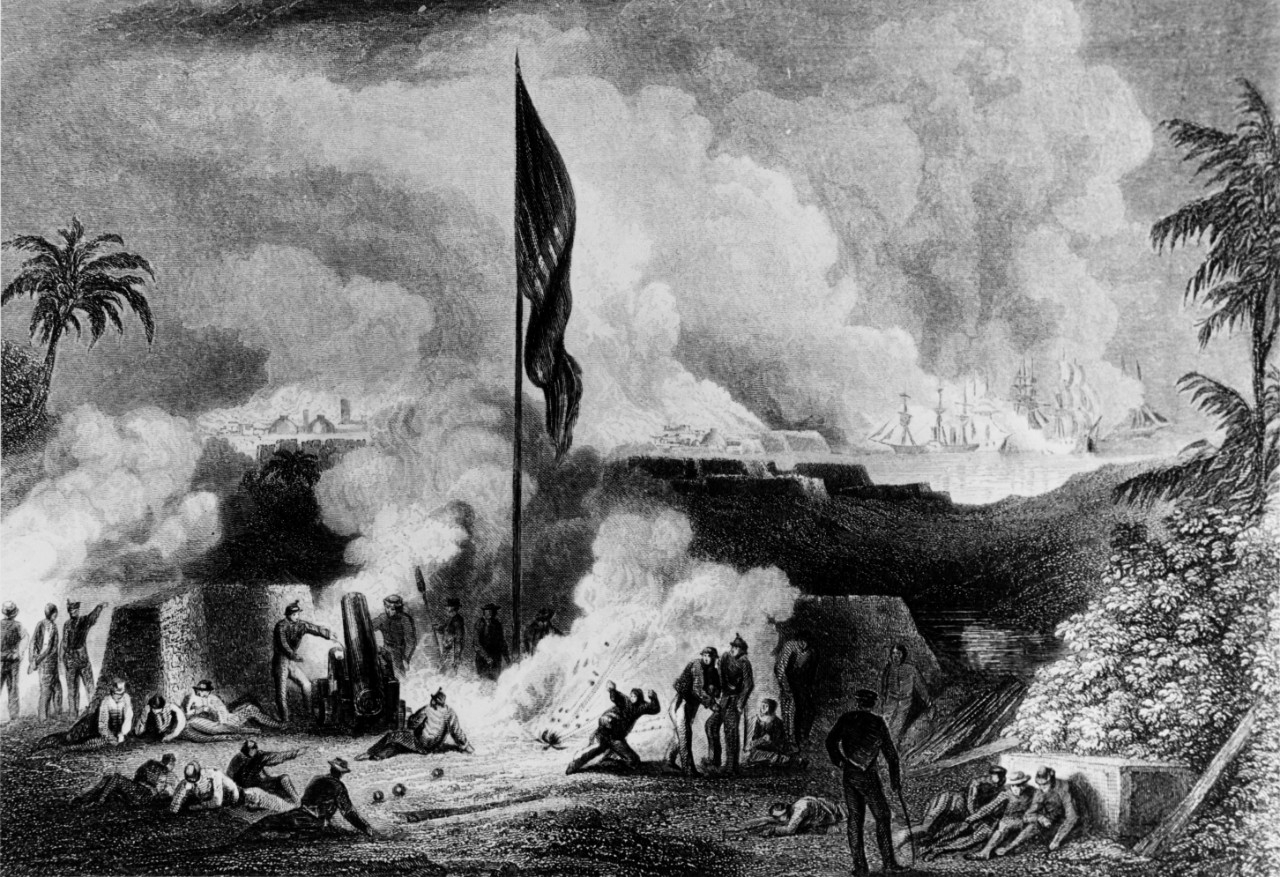

On May 13, 1846, Congress, despite widespread unpopularity of the issue among the American public, declared war on Mexico. The catalyst for the dispute stemmed from the U.S. annexation of Texas in December 1845 and whether Texas territory bordered on the Nueces River (Mexican claim) or on the Rio Grande (American claim). Expansionist-minded President James K. Polk believed that the United States had a “manifest destiny,” which was to expand the nation across the continent all the way to the Pacific Ocean. Opposition to the war stemmed from the belief that more land acquired by the United States would just create more states in which slavery would be legal. When war broke out, former Mexican president Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna contacted Polk in attempt to broker a peace agreement. However, instead of working toward peace, Santa Anna, who at the time was in exile in Cuba, deceived Polk and took charge of Mexican forces.

After all negotiations had failed, Polk ordered U.S. Army forces in the Rio Grande area, under Gen. Zachary Taylor, to invade Mexico while a second force, under Col. Stephen Kearny, was to occupy New Mexico and California. Kearny’s troops met little resistance while Taylor’s troops fought several battles south of the Rio Grande and defeated a major Mexican force during the Battle of Buena Vista. However, Taylor showed little interest in moving deeper into Mexico, and a frustrated Polk had to revise his war plans. He ordered Gen. Winfield Scott to take his army by sea to Veracruz, capture that key seaport, and march to Mexico City. Despite Mexican resistance, Scott’s campaign was marked by a series of victories, and he entered Mexico City on Sept. 14, 1847. The fall of the Mexican capital ended the fighting on land and at sea.

Navy involvement in the Mexican-American War included blockades and operations on the Pacific coast and Gulf of Mexico. Under the command of Commodore John Sloat and Commodore Robert Stockton, the Pacific Squadron ensured success in the California campaign with the capture of San Francisco and San Diego. From the Gulf of Mexico, Commodore Matthew Perry navigated his force through small rivers and waterways to capture enemy strongholds and block supply routes. Commodore David Conner was instrumental in the landing of 22,000 troops in Veracruz, which was, at the time, the largest amphibious operation in American history.

On Feb. 2, 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, formally ending the war. Mexico agreed to an extension of Texas’s southern border to the Rio Grande and ceded present-day California, New Mexico, Utah, and Nevada, as well as parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming, to the United States.

Infection and disease made up most of the U.S. casualties during the Mexican-American War. At least 10,000 troops died of illness, whereas some 1,500 were killed in action. Poor sanitation was mostly to blame for the deaths. Yellow fever was rampant, but other diseases such as measles, mumps, and smallpox also took their toll.

After the war, Taylor emerged a national hero and would succeed Polk as president in 1849. The acquisition of more land did open the issue of the legality of slavery in the newly acquired territory. After coming dangerously close to a civil war, the status of slavery in the new region was resolved in part by the Compromise of 1850, which admitted California to the Union as a free state and left the issue of slavery in the other territories up to the courts. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, many of the most noteworthy generals on both sides credited their battle experience to the Mexican-American War. However, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant later called the Mexican War “one of the most unjust ever waged against a weaker nation.”

Triton’s Circumnavigation of the Earth

Dubbed Operation Sandblast, USS Triton (SSR[N]-586), commanded by Capt. Edward L. Beach, completed the first submerged circumnavigation of the earth on May 10, 1960. During the voyage, Beach followed many of the same routes taken by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan’s 16th-century circumnavigation. The submarine did have to surface once during the voyage when it transferred a sick Sailor to USS Macon (CA-132) off Montevideo, Uruguay, on March 6. The historic trip began when Triton was put to sea for its shakedown cruise on Feb. 15, bound for the South Atlantic. It arrived in the mid-Atlantic off St. Peter and St. Paul Rocks on Feb. 24 to commence the voyage. Having remained submerged since its departure from the U.S. East Coast, Triton continued south toward Cape Horn, rounded the tip of South America, and headed west across the Pacific. After transiting the Philippine and Indonesian archipelagoes and crossing the Indian Ocean, Triton rounded the Cape of Good Hope and arrived off the St. Peter and St. Paul Rocks again on April 10, 60 days and 21 hours after departing the mid-ocean landmark. It arrived back at Groton, Connecticut, a month later, having completed the historic voyage.

Triton’s underwater globe-trotting cruise proved politically invaluable to the United States during the Cold War. From an operational standpoint, the cruise demonstrated the great submerged endurance and sustained high-speed transit capabilities of the first generation of nuclear-powered submarines. Moreover, during the voyage, the submarine collected reams of oceanographic data. At the cruise’s conclusion, Triton received the Presidential Unit Citation, and Beach was awarded the Legion of Merit by President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Triton, originally a radar picket submarine and the only member of its class, had the distinction of being the only U.S. Navy submarine with two nuclear reactors. It was part of the Navy’s first generation of nuclear submarines, along with Nautilus (SSN-571), Seawolf (SSN-575), Halibut (SSG[N]-587), and the Skate-class boats. Nautilus introduced the use of nuclear power for propulsion purposes. Seawolf utilized a pressurized water cooled reactor. Halibut was the first nuclear-powered submarine to conduct a strategic nuclear deterrence patrol armed with Regulus cruise missiles. The Skate-class submarines were the first nuclear-powered submarine class with more than one boat built. When Triton was commissioned on Nov. 10, 1959, it was the largest, most powerful, and most expensive submarine ever constructed ($109 million), excluding the cost of nuclear fuel and the reactors. Developed after World War II, radar picket submarines were designed to provide intelligence, electronic surveillance, and fighter aircraft interception control. Unlike destroyers that performed radar picket duties during the war, submarines could just submerge if detected. Triton was ideal for picket duty due to its speed and endurance.

After Triton’s historic first deployment, its next voyage took it to European waters to participate in NATO exercises geared toward detecting Soviet bombers flying over the Arctic. The following year, it continued to take part in exercises with the Atlantic Fleet, conducting operations to counter the increasing Russian submarine threat. Triton was redesignated SSN-586 on March 1, 1961, and entered Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Maine, for conversion to an attack submarine in June 1962. Upon completion in March 1964, Triton changed homeport from New London, Connecticut, to Norfolk, Virginia. Beginning in April 1964, the submarine served as flagship for Submarine Force, Atlantic Fleet, and remained in that role until June 1967.

Due to budget cuts in defense spending, Triton’s scheduled 1967 overhaul was cancelled indefinitely, and the submarine, along with 50 other vessels, was inactivated. Triton was decommissioned on May 3, 1969, making it the first nuclear submarine to be withdrawn from service. It remained in the inactive fleet until mid-2007 before scrapping commenced.

The USS Triton Sail Park in Richland, Washington, is open to the public and displays a well-preserved conning tower and the groundbreaking submarine’s command center. For more on the Submarine Force, visit NHHC’s website.

![USS Triton (SSR[N]-586) underway USS Triton (SSR[N]-586) underway](/content/history/nhhc/news-and-events/news/2023/nhm-050223/_jcr_content/articleParbody/media_asset_1443007125/image.img.jpg/1683031377409.jpg)