Note: NHHC will not publish Navy History Matters on Dec. 26, 2023. We will resume our biweekly compilation of naval history on Jan. 9, 2024. Happy Holidays!

Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

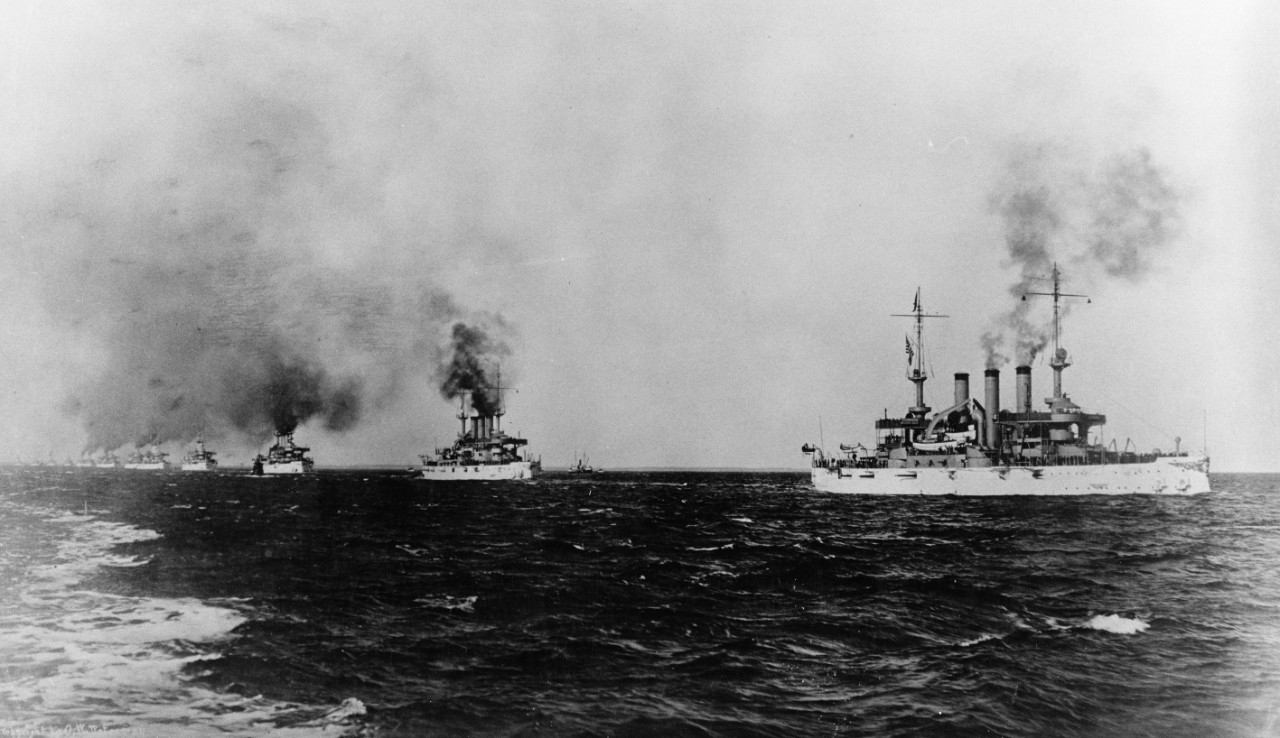

Great White Fleet Began Global Cruise

On an unseasonably warm, cloudy morning on Dec. 16, 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet—a force of 16 battleships bristling with guns and painted sparkling white— departed Hampton Roads, Virginia, to begin what would become a 43,000-mile, 14-month circumnavigation of the globe. The four-mile-long armada’s world tour included 20 port calls on six continents. Fourteen thousand Sailors and Marines participated in the three-leg voyage, leaving a lasting legacy at home and abroad. It was widely considered one of the greatest peacetime achievements of the U.S. Navy, and it made Roosevelt’s message clear: “America is a respected world power, with a strong Navy leading the way.”

The Great White Fleet cruise had dual origins—a diplomatic crisis with Japan and a need to test new U.S. battleships. On June 27, 1907, at the height of tensions in Japanese-American relations, Roosevelt decided to send the Atlantic battleship fleet to the Pacific in the fall. With nearly all U.S. battleships in the Atlantic Fleet, the U.S. naval force in the Pacific was no match for the Imperial Japanese Navy. Aware of this situation, residents on the U.S. West Coast felt vulnerable to an attack. Coinciding with tensions with Japan, the Atlantic Fleet possessed a sufficient number of new first-class battleships available for sustained operations. Roosevelt seized the opportunity and ordered these ships to the Pacific. The exercise would test the new battleships’ mechanical systems and their ability to reach the Pacific in good condition to engage an enemy, as well as bolster the security of the West Coast. On July 2, Secretary of the Navy Victor Metcalf announced that the fleet would steam around Cape Horn on a practice cruise and would later make its way to the San Francisco Bay. He mentioned nothing about the fleet’s route back to the Atlantic because he wanted to remain flexible in case a circumnavigation of the globe proved impractical. The administration would wait with an announcement of intent until the fleet reached the west coast of Mexico. If it had no major mechanical difficulties, the U.S. government would officially state that the fleet would return to the Atlantic by way of Australia, the Philippines, the Suez Canal, and the Mediterranean.

When the first leg of the trip began, the battleships departed Hampton Roads for their first stop at Port of Spain, Trinidad, where they anchored on Dec. 23 to coal. The fleet crossed the line on Jan. 6, 1908, and anchored in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, six days later. From there, it proceeded south to Punta Arenas, Chile, where the ships stopped once again to coal. After passing through the Strait of Magellan without any problems, the fleet paraded through the harbor of Valparaiso, Chile, without stopping, then continued north. On Feb. 20, it arrived at Callao, Peru. During every port call, officers attended formal receptions, and Sailors enjoyed liberty ashore. After pausing a month in Magdalena Bay off Mexico’s Baja California, the fleet reentered U.S. territory and dropped anchor at Coronado, California, on April 14. Four days later, the fleet steamed north to Los Angeles. On the way to San Francisco, the fleet visited the California ports of Santa Barbara, Monterey, and Santa Cruz. Over the course of nearly three months, elements of the fleet visited cities up and down the West Coast. The entire fleet visited Seattle. Some of its ships went into dry dock at Bellingham, Washington, to have their hulls cleaned, while others returned to San Francisco.

On July 7, the entire fleet departed San Francisco for the second leg of the cruise across the Pacific. On July 16, the ships arrived at Honolulu, Hawaii, where the officers enjoyed luaus and sailing regattas. The ships departed six days later, reaching Auckland, New Zealand, on Aug. 9. After six days of festivities there, the fleet proceeded to Australia, spending nearly a month down under visiting the ports of Sydney, Melbourne, and Albany. On their way to Japan, the fleet made a stop at Manila in the Philippines, where a cholera epidemic prevented Sailors from taking liberty in the city. Yokohama, Japan, extended its hospitality to the fleet for a week, beginning Oct. 18. Following a visit to Amoy (present-day Xiamen), China, the fleet practiced gunnery in Manila Bay.

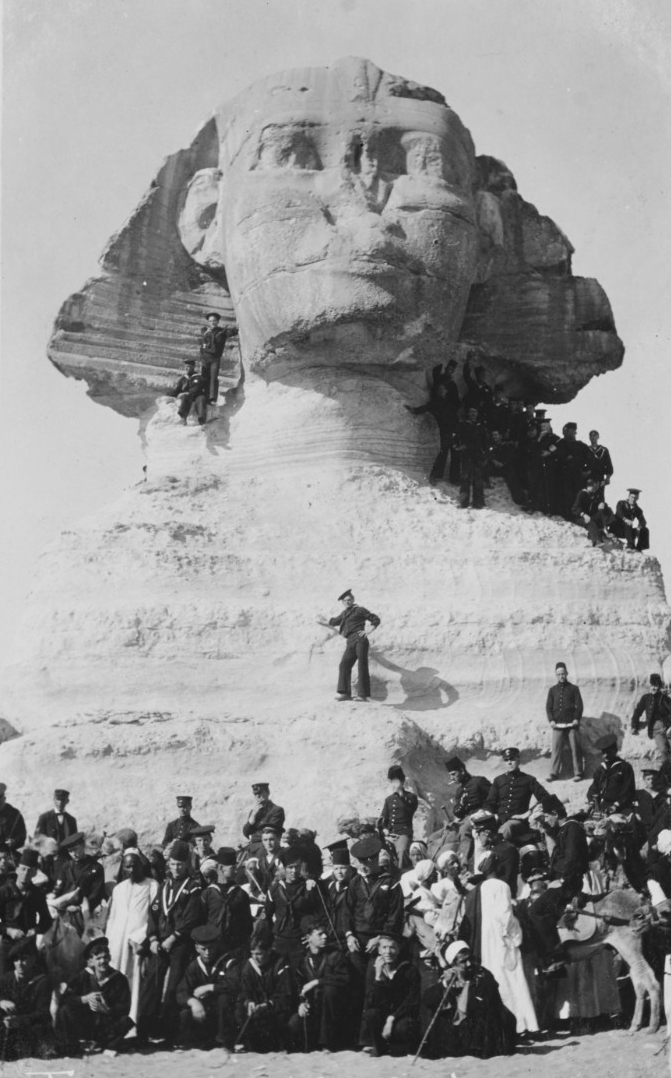

On Dec. 1, the Great White Fleet departed Manila for the third and final leg of the cruise. It made way through the South China Sea, the Strait of Malacca, and the Indian Ocean to Colombo, Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), where it remained for a week. After traversing the Arabian Sea, Gulf of Aden, and the Red Sea, the fleet arrived at Suez, Egypt, on Jan. 3, 1909. It then passed through the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean Sea. During that month, the fleet split up to make several port calls, including Algiers, Tripoli, Naples, Marseille, Athens, and Malta, while several ships were detached on an international humanitarian mission to aid victims of a devastating earthquake and subsequent tsunami that hit the southern Italian towns of Sicily and Messina. By Feb. 6, the fleet had rejoined at Gibraltar. On Feb. 22, the Great White Fleet arrived back home in Hampton Roads, completing a circumnavigation of the globe just two weeks before Roosevelt left office.

The world cruise of the Great White Fleet was a resounding diplomatic victory for the United States. Besides demonstrating that the U.S. Navy could project power globally, the cruise improved relations with many countries, notably Australia and Japan. The cruise also fulfilled Roosevelt’s expectation that the Great White Fleet would help educate the American public about naval operations and stimulate widespread support for the U.S. Navy. Moreover, it provided Navy personnel with practical experience in sea duty and ship handling, leading to improved formation steaming, fuel economy, and morale.

Shortly after their arrival back home, the ships underwent major changes to their appearance. New cage masts with fire-control tops replaced old-style masts with fighting tops, and the ships were repainted battleship gray. All too soon, though, they would become obsolete with the launching of the Royal Navy’s HMS Dreadnought, which revolutionized naval power with its steam turbines and all-big-gun armament. Nonetheless, the world cruise of the Great White Fleet invigorated a national commitment to naval power and solidified the United States as a respected world power with a Navy second to none.

The Saga of Saginaw

On Dec. 19, 1870, Coxswain William Halford, the lone survivor of a rescue mission, reached the Hawaiian Islands after a month at sea in a makeshift 25-foot boat. Halford, along with four others, were seeking help for the crew of side-wheel steamer Saginaw that was wrecked on a deserted island about 50 miles away from Midway. Saginaw was at Midway to support dredging operations to deepen the entrance to the harbor, completing its portion of the mission on Oct. 21. A week later, Saginaw steamed for San Francisco intending to stop at Ocean Island (now called Kure Atoll) to possibly rescue any shipwrecked Sailors who might be stranded there (it was a known location for ships to be grounded on the reef). The next day, on Oct. 29, as Saginaw neared the rarely visited island, the ship struck an outlying reef and was ultimately grounded. Before the surf battered the ship to pieces, its crew managed to transfer much of its gear and provisions to the island. Miraculously, none of the crew died during the ship’s grounding. Many were wounded with foot and skin lacerations from the sharp reef. One member of the crew broke his clavicle as the waves pushed him against the coral.

Over the next several days, the crew set up camp, scavenged for wreckage and other supplies that may have been pushed to shore, and began to adapt to life as castaways. Food and water were in short supply, the latter being more of a concern. As luck would have it, the diving contractors that were on Saginaw had with them an auxiliary boiler that was recovered intact. The crew was able to use the boiler to produce steam, which was then condensed and distilled, providing freshwater. The crew was reduced to rations while fishing, and the culling of the local seal and albatross population helped supplement the food stores from Saginaw. Medical issues became more prevalent as time went on. An outbreak of dysentery from the high-fat, high-oil, and low-carb diet ravaged the crew. Lt. Cmdr. Montgomery Sicard, Saginaw’s commanding officer, very quickly realized that given their location, and the lack of vessel traffic in the area, they could not wait for the unlikely coincidence of a passing ship. After being stranded for only three days, Sicard gathered the crew and informed them that he would assemble a team to sail to Honolulu to obtain assistance.

Of the boats available, only the captain’s gig (currently in the collections of NHHC) was deemed worthy for the lengthy journey. The crew brought the whaleboat onto shore and began the process of getting it ready for the rescue attempt. It was decked over with wood salvaged from Saginaw, then canvassed. Metal was used to reinforce the gig’s bow, and the boat was stepped for two masts, with appropriate-sized sails fashioned from Saginaw. All of the modifications were repurposed wood, nails, copper, and sails from the wreck of their former vessel. As preparations were underway, Sicard had to make the decision which crewmembers would take on the dangerous mission. The executive officer, Lt. John G. Talbot, enthusiastically volunteered to lead the effort. Others chosen were a mix of experienced Sailors and men from the contractor dredging crew. In part, the decision was made due to who was in the best health, as many of Saginaw’s Sailors were simply no longer physically fit to make the hazardous voyage. Quartermaster Peter Francis and Halford from the ship’s regular crew volunteered. James Muir and John Andrews, both contract divers from Boston, were also selected to round out the rescue crew. The boat was provisioned with food for 35 days—the estimated time it would take to reach Hawaii—and it was outfitted with a small heating apparatus and lamp. Sufficient oil and water was also placed inside the boat’s hold. An engineer from the crew was able to construct a rudimentary sextant from spare parts from Saginaw’s steam engines, a shaving mirror, and various other metals salvaged from the ship.

In the late afternoon of Nov. 18, the crew of Saginaw gathered on the shore, recited a prayer, and launched the small gig into the water. Instead of a direct route, which was impossible due to prevailing winds and currents, Talbot steered the boat to the north, then east to the appropriate longitude of Honolulu. The adjusted course ultimately extended the journey by hundreds of miles. After only five days, the lamp was extinguished and all their tinder was waterlogged. The boat constantly leaked, which meant the men had to continually bail water from the boat. Their bread spoiled; the coffee, tea, and sugar were ruined by the seawater; and someone had mistakenly placed molasses in the rice and beans, causing it to ferment. They lost all their ability to heat food, and at one point they desperately grabbed an albatross and ate it raw. Muir and Andrews were sick for most of the voyage. Talbot was struck by severe diarrhea and was ill for more than a week. Only Halford and Francis were able to stay relatively healthy, though both suffered from extreme malnourishment. After 28 days at sea, land was finally sighted. It was Kaula Rock, a small uninhabited rock formation southwest of Kauai, the nearest of the Hawaiian Islands that could hopefully rescue Saginaw’s crew. At this point in the journey, all five men were so exhausted that Talbot knew they would never make it to Honolulu. The crew spent the next several days tacking into the wind to make landfall on the north shore of Kauai. As they approached Hanalei Bay on the evening of Dec. 18, they decided to wait until morning to make their approach, as the rough seas close to shore made this part of their journey the most perilous. Halford had come off watch, relieved by Talbot, when he went to rest. Shortly afterward, he was awakened by the motion of the boat capsizing. He woke Muir, who was also resting, and told him they needed all hands on deck. Muir stayed and once Halford was awake, a wave washed the men overboard. Talbot ordered the boat to change course, but another breaker overtook the small gig and capsized the boat. Francis and Andrews were washed away with that wave and drowned. Muir was still trapped below deck while Talbot was in the water. Halford, still on the gig, tried to help Talbot get back on the gig, but another breaker rolled the boat again. Talbot tragically drowned without muttering a sound.

As the ordeal continued, the small boat was tossed about in the breakers, but finally rolled upright again, allowing Muir to get on deck. His wounds were not apparent at the time, but he was incoherent and unable to assist Halford. The gig rolled two more times before moving past the breakers and into calmer water. They later arrived on the western side of Kalihikai, 4–5 miles east of Hanalei Bay, 31 days from when they left Ocean Island. Halford assisted Muir to shore, who groaned constantly in pain, then made several trips from the boat to shore to ferry letters, supplies, and equipment. Wounded himself with a piece of mast buried in his leg, Halford passed out after removing it. He woke several hours later to find a local man leaning over and looking at him. Halford immediately went looking for Muir, who was no longer on the beach. Muir’s body was later located some distance away, his head and face severely blackened. He likely experienced head trauma when the gig rolled in the surf. After being clothed and fed by the locals, Halford went in search of someone who could help rescue his shipmates. He found a ship captain who was willing to travel to Oahu, landing there on Christmas Eve. Halford immediately went to the U.S. Consul’s Office and reported the dire situation to Minister Henry Peirce, who in turn chartered the 85-ton fast-sailing schooner Kona Packet to sail to Ocean Island. While in the process of chartering a second vessel as back up, Halford was informed that his petition to King Kamehameha V was received and the Hawaiian kingdom dispatched the 399-ton wood screw steamer Kilauea to assist with the rescue.

Meanwhile, back on Ocean Island, the crew was in the process of building a schooner from Saginaw’s wreckage. The ship, named Deliverance by the crew, would be a backup in case Talbot’s rescue crew did not make it to Hawaii. On Jan. 3, 1871, much to the crew’s elation, they sighted Kilauea with Kona Packet arriving shortly afterwards. Hoping to see their shipmates, Sicard was informed of the gig’s voyage and the ultimate sacrifice made by four of the crew. Celebration turned to sorrow when the crew learned of their shipmates’ fates. Two days later, the crew was loaded on Kilauea, the larger of the two vessels, and started their journey to Honolulu, arriving on Jan. 14. Remarkably, the crew that stayed on Ocean Island survived the ordeal, and the only casualties suffered were those that sailed to Hawaii on the captain’s gig. The sole survivor of the rescue mission, Halford, was awarded the Medal of Honor, promoted to acting gunner’s mate, and continued to serve in the Navy, eventually retiring as a lieutenant. For a more detailed account of the Saginaw saga, read H-Gram 057-3 by NHHC Director Sam Cox at NHHC’s website.

River Patrol Force Established

On Dec. 18, 1965, the River Patrol Force (Task Force 116) was established during the Vietnam War. The establishment of the task force was in response to the guerilla warfare that required operators to fight inland on the country’s maze of rivers. The mission was to keep shipping channels open, search river craft, disrupt enemy troop movements, and support special operations and ground forces. Dubbed Operation Game Warden, the task force performed harassment and interdiction operations, river patrols, and minesweeping operations, especially along the main Saigon shipping channels. They were authorized to board and search all river craft—except foreign-flagged steel-hull merchant ships; warships and military vessels; and police or customs craft, unless specifically authorized by the task force commander. Shortly after the force was established, a new kind of small craft arrived at Cat Lo, a major U.S. naval base on the northern shore of Cape Vung Tau. The craft was designated patrol boat, river (PBR). It was a high-speed, diesel-powered freshwater patrol craft with a fiberglass hull and water jet propulsion. It became an integral part of the “Brown Water Navy.”

Over the next few years, hundreds of PBRs were delivered to U.S. and South Vietnamese forces. PBRs were armed with twin .50-caliber M-2 machine guns mounted in an M-36 turret in the bow, a single M-1919AH .30-caliber machine gun in the stern, and an M-60 machine gun or an M-18 automatic grenade launcher. Four enlisted Sailors manned the vessels, which consisted of a boat captain, an engineman, a gunner’s mate, and a seaman. A fifth person, such as a South Vietnamese police officer or customs officer, would sometimes accompany the boats on patrol.

When riverine operations commenced, the Navy faced a task it hadn’t handled since the Union Navy took control of the Mississippi River and its tributaries from the Confederacy. The most daunting freshwater patrol area was the outlet of the Mekong River, the Mekong Delta, comprising of about one-quarter of the total land area of South Vietnam and containing up to half the country’s population. The Mekong Delta held more than 4,000 miles of waterways. Many of the banks were lined with dense vegetation that provided the perfect cover for the enemy. In 1968, it was estimated that 80,000 Viet Cong operated in the Mekong Delta region. The delta was divided into three regions: the Plain of Reeds, an immense, vegetated marsh with water 1 to 6 feet deep; the rice paddies, where most of the population lived and where most riverine patrols occurred; and the mangrove swamps, which included the Rung Sat Special Zone around the ship channel to the ports at Saigon. The standard for patrols was two boats that cruised within radar range of each other, up to 1,000 yards. Patrols usually lasted about 12 hours. One of the main tasks for PBR units was curfew enforcement, generally from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m.

Initially, PBRs played limited roles in offensive operations, although they did set ambushes at suspected Viet Cong river crossings. During a March 1967 search-and-destroy mission designated Overlord II, six PBRs provided gunfire support and waterway blockade to prevent the escape of North Vietnamese guerrillas pursued by U.S. Army units on shore. Eventually, the Army fielded their own amphibious unit—the 458th Transportation Company. The crews were trained by the Navy and operated “J-Boats” to distinguish themselves from the Navy boats. Before the Tet Offensive in early 1968, PBRs that were attacked by shore fire returned fire and immediately departed the area while calling for support. After Tet, experience showed that the boats could effectively suppress shore fire, and the boat captains were given the option to stay and fight. As the war wound down, Army and Navy PBRs were turned over to the South Vietnamese. In Dec. 1970, the Navy transferred its PBR resources to the Vietnamese navy, and the 458th deactivated about a year later.

Today in Naval History—Last Apollo Mission to the Moon

On Dec. 12, 1972, Capt. Eugene A. Cernan, commander of Apollo 17, set foot on the moon and raised the American flag to mark the monumental moment. In his company for Apollo’s final mission, Cmdr. Ronald E. Evans was the command module pilot, and geologist Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt was the lunar module pilot. It was Cernan’s third and final spaceflight, and it was Evans’s and Schmitt’s first. In fact, Schmitt was the first and only geologist to set foot on the moon. Notably, Cernan and Evan’s were both naval aviators.

While Evans remained in orbit in the command module America, Cernan and Schmitt spent 75 hours on the moon and performed three extra-vehicular activities (EVAs, or “moonwalks”), totaling 22 hours and 4 minutes. Both the total EVA time and the total time on the lunar surface were the longest of the Apollo program. The first EVA began just 4 hours after landing and lasted for more than 7 hours. The crew began by deploying the lunar rover and then set up the Apollo lunar surface experiment package about 180 meters west of the lunar module. During the EVA, a heat flow experiment, a mass spectrometer to measure the composition of the fragile lunar atmosphere, an experiment to measure the size and velocity of micrometeorites striking the moon, and an attempt to measure gravity waves predicted by the Theory of Relativity were conducted. Then, the astronauts made a short 3.3-kilometer roundtrip drive to the Steno crater, south of the landing site, to sample basalts in the central part of the Taurus-Littrow Valley. On all three EVAs, the crew measured how the strength of the moon’s gravity varied in different locations and deployed eight small explosive charges as part of a lunar seismic profiling experiment. The explosives were activated after the crew left the moon, and both experiments provided data on the structure of the crust across the valley floor.

The second EVA was the longest of the Apollo program both by duration, 7 hours and 37 minutes, and by distance—more than 20-kilometers round trip. Cernan and Schmitt began the EVA by repairing the right rear fender of the lunar rover using laminated maps and small clamps. The fender had been damaged when it was snagged by a rock hammer during the first EVA. After the repair, they made their way to the base of the South Massif landslide and to the Camelot Crater, where they took more samples that included boulders, basalt, and orange soil. The orange soil turned out to be 3.6 billion-year-old pyroclastic glass from an ancient volcanic eruption. On the third EVA, lasting 7 hours and 15 minutes, Cernan and Schmitt made a 12-kilometer round-trip drive, making three stops along the North Massif and the Sculptured Hills, northeast of the landing site. At the first stop, they reached an elevation of about 80 meters above the plains where they landed. Although the rover handled the climb easily, the crew found it difficult to work on the steep 20-degree slope on the flank of the North Massif. A large boulder was discovered that was split into several pieces totaling 25 meters across. Its downward track showed it had originated about one-third of the way up the North Massif and rolled about 500 meters down slope, allowing the crew to sample material from high above the valley floor that they could not have otherwise reached. The boulder was a complex, vesicular breccia, varying in composition from one end of the boulder to the other. Additional boulder samples were obtained further east along the base of the North Massif and at the base of the Sculptured Hills. Finally, they made their way to the Van Serg Crater on the valley floor. Pre-mission analysis projected the crater to be a possible volcanic vent, but it turned out to be an impact crater with a very rocky rim. During the three EVAs combined, Cernan and Schmitt collected 110.5 kilograms of lunar samples. They drove the lunar rover for a total distance of more than 35 kilometers.

While Cernan and Schmitt were on the moon, Evans remained in lunar orbit in the command module where he took images and conducted a set of orbital experiments. As on Apollos 15 and 16, he used high-resolution mapping cameras and a laser altimeter to chart the moon’s surface. Evan’s also conducted the lunar sounder experiment, which was a subsurface sounding radar that imaged structures in the lunar crust more than a kilometer below the lunar surface. In addition, the ultraviolet spectrometer experiment measured the composition of the lunar atmosphere, and the infrared radiometer experiment measured how the temperature of the lunar surface changed during the lunar day and night. Evans also made visual observations, guided by detailed cue cards created prior to launch. Apollo 17 spent a total of 6 days and 3 hours in lunar orbit, circling the moon 75 times. While on the return voyage to Earth, Evans made a 1-hour spacewalk to collect the film cassettes from the mapping cameras and the sounding radar, which were located in the scientific instrument module. The crew landed in the Pacific Ocean on Dec. 19 after a flight of 12 days and 13 hours. Aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga (CV-14) recovered the spacecraft and the astronauts about 350 nautical miles southeast of American Samoa. For more on the Navy’s role in space exploration, visit NHHC’s website.