H-057-3: The Saga of the Saginaw Gig

H-057.3

Samuel J. Cox, Director, Naval History and Heritage Command

January 2021

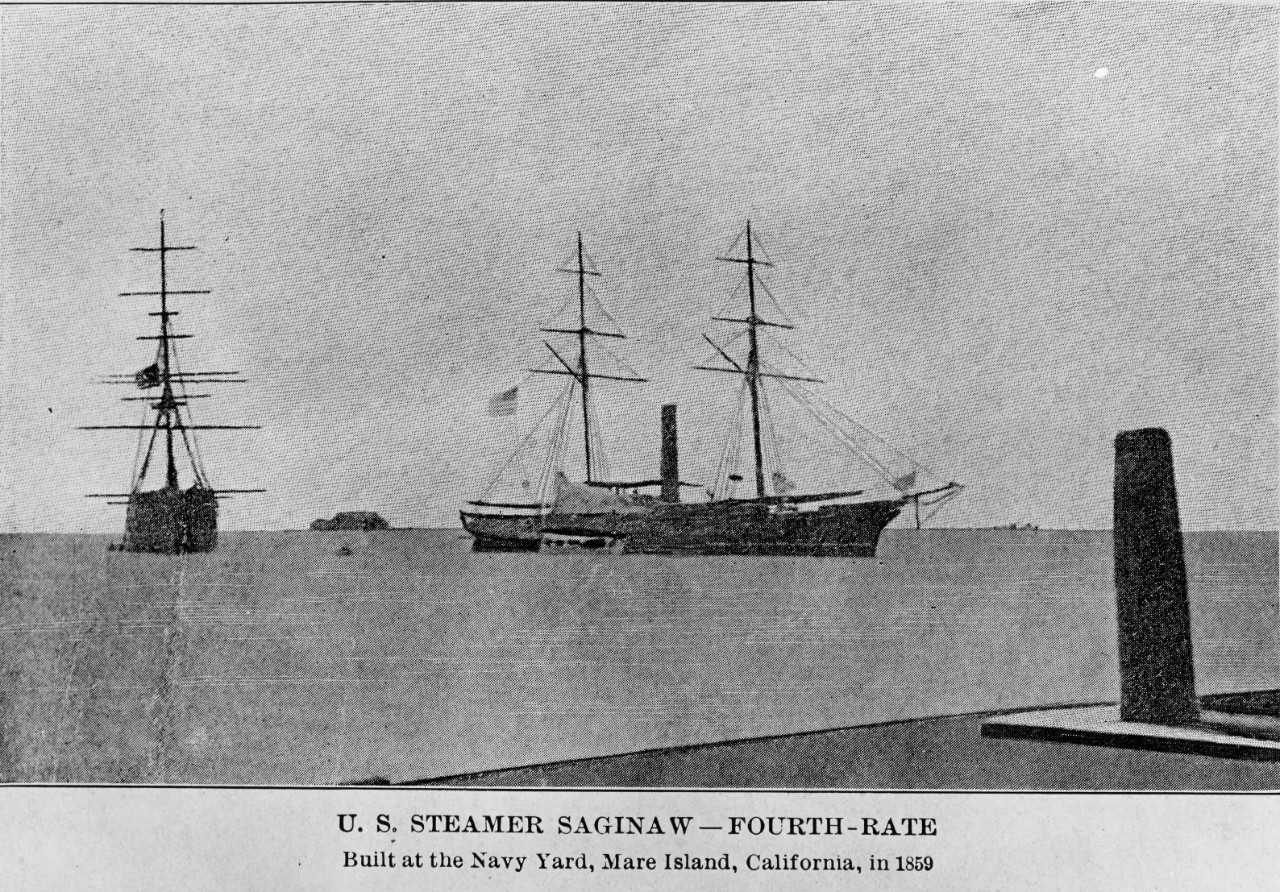

The steam sidewheel sloop-of-war Saginaw was the first ship built at the Mare Island Navy Yard, California, and was commissioned on 5 January 1860. She first served with the U.S. Navy East India Squadron. While searching for the crew of the missing American bark Myrtle on 31 July 1861, Saginaw was fired on by a battery at the entrance to Qui Nhon Bay, Cochin, China (now Vietnam). At the time, French and Spanish expeditionary forces were engaged in a punitive action due to Vietnamese killing of French and Spanish missionaries (the Vietnamese actually put up a really good fight against the Europeans). Despite Saginaw flying a white flag of neutrality, the Vietnamese fort continued to fire on Saginaw with three near misses. Saginaw subsequently returned fire and in a 40-minute bombardment destroyed the fort. Lacking enough manpower for a landing party, Saginaw then withdrew.

During the Civil War, Saginaw served in the Pacific Squadron and patrolled the west coasts of the U.S., Mexico, and Central America to guard against Confederate and European interference, spending most of 1865 at Guyamas, Mexico, protecting U.S. citizens during the fighting between Emperor Maximilian I (installed by the French in 1864 and executed by the Mexicans in 1867) and Mexican President Benito Jaurez (who was fighting to kick the French invaders out). In 1868, Saginaw bombarded and burned three Alaskan Native villages near Sitka, Alaska, in what was known as the Kake War (after the Alaskan tribe involved, which had killed two white trappers in retaliation for the killing of two Kake men at Sitka). Although the villages were deserted at the time except for one old woman, the destruction of stores and shelter for the winter resulted in an undetermined number of Kake deaths due to deprivation, in addition to the elder woman. Although U.S. Navy personnel provided support to Andrew Jackson’s campaign against the Seminole Indians in Florida (1835-1842), this is the only case of a U.S. Navy ship firing on Native American targets that I am aware of. The whole story of the “Kake War” is one of a long list of examples of Native Americans being treated badly and unfairly. (Someday I will write an H-Gram on “Battles You’ve Never Heard Of” about all the battles around the world that the U.S. Navy was involved in during the 1800s and early 1900s)

On 24 March 1870, Saginaw arrived at Midway Atoll at the far northwestern end of the Hawaiian Islands (then known by Americans and Europeans as the Sandwich Islands, named by British Captain James Cook in 1778 after the then-First Lord of the Admiralty, John Montague, the 4th Earl of Sandwich, who supposedly invented the sandwich so as to be able to eat while he gambled). Under the command of Commander (promoted 2 March 1870) Montgomery Sicard, Saginaw was assisting with efforts by civilian contractors to widen the channel into the lagoon in order to establish a U.S. Navy coaling station. By October 1870, this effort was deemed infeasible with the resources of the time, and on 27 October, Saginaw brought all contractors on board to return to San Francisco and departed the next day. However, CDR Sicard decided to check at Kure Atoll (then known at Ocean Island), about 50 miles northwest of Midway, for any possible stranded shipwreck survivors.

Despite proceeding with extreme caution at very slow speed, with extra lookouts posted, currents caused Saginaw to reach Kure several hours before anticipated, and in predawn darkness of 29 October 1870, Saginaw ran hard aground on an outlying reef. Quickly determining that the ship could not be saved, CDR Sicard directed the crew in a valiant effort to get as many supplies and gear off the ship and onto boats before she began to break up in heavy surf. Somewhat miraculously all 93 aboard (about half the ship’s crew and half contractors) reached shore in the boats and by wading to the main part of the island, although there were a number of significant injuries, mostly from cuts on the sharp reef coral. Although food and water were in short supply, seals and albatross supplemented the remaining rations. A boiler belonging to the contractors was saved intact from the wreck─it was used to make steam, which then condensed, providing distilled fresh water. Nevertheless, dysentery quickly affected most of the crew. Within three days, CDR Sicard determined that passively waiting for rescue was not the best option.

The captain’s 22-foot gig, which had survived the grounding, was extensively modified to help it withstand a 1,400-mile trip to Oahu. An extra eight inches of freeboard was added to the open whaleboat, the bow was strengthened with iron, the boat decked over, and two masts were added to handle modified sails recovered from Saginaw.

The five-man volunteer crew for the voyage was led by the executive officer, Lieutenant John Talbot, and included two ship’s crew, Quartermaster Peter Francis and Coxswain William Halford, and two contractors (both hardhat divers), James Muir and John Andrews. Sicard enlisted the two civilians into the Navy. There were other volunteers, but CDR Sicard selected those deemed most healthy and physically fit to withstand what was expected to be an arduous journey. With provisions intended to last 35 days and a rudimentary sextant, the boat left Kure on 18 November to the prayers of those left behind.

Due to prevailing winds and currents, LT Talbot would have to navigate the boat well north of the Hawaiian Islands, turning south only when reaching the longitude of Oahu. Things quickly went south on the boat, however. Within a few days the lamp and heater were out and all tinder waterlogged. The boat required constant bailing to remain afloat. Coffee, tea, and sugar were ruined by salt water. The bread spoiled and molasses in the rice and beans fermented. Quickly running short of food, Halford managed to grab an unlucky albatross, which got its posthumous revenge after the men ate it raw, causing Talbot and two men to become extremely sick for the rest of the trip. Despairing that they would survive, the five men etched their names near the after hatch.

Land was finally sighted after 28 days, which turned out to be the rough north shore of Kauai near Hanalei Bay. Approaching shore before sunset on 18 December, LT Talbot intended to wait until daybreak to attempt a landing. However, during the night the boat was carried into the heavy surf. As the boat tumbled in the breakers, Francis and Andrews were washed overboard and in their weakened state quickly drowned. Halford tried to pull LT Talbot (who was also debilitated by sickness) out of the water, but another wave washed Talbot away. Halford succeeded in getting Muir out from below and assisted to him to shore, but Muir had apparently suffered a severe head injury in the tumbling boat, and by the next morning Muir had died, leaving Halford as the only survivor.

Helped by local islanders, Halford found a ship captain who willingly left his load behind on Kauai to immediately take Halford to Honolulu on the schooner Wainona, arriving on Christmas Eve. The U.S. Consul’s Office chartered a fast schooner Kona Packet, and King Kamehameha (ruler of the still independent Kingdom of Hawaii) sent the wooden screw steamer SS Kilauea. On 3 January Kilauea arrived at Kure and Kona Packet shortly afterwards. Saginaw’s crew was in the process of constructing a 40-ton schooner from the remains of Saginaw, named the Deliverance. (CDR Sicard was aware that in 1837 the British whaler Geldstanes wrecked on Kure, and her crew constructed a boat out of her remains and named it Deliverence, which reached Honolulu, and all of Geldstanes crew were rescued after many months on the atoll). CDR Siccard’s joy turned to sorrow when he learned the fate of the volunteers on the gig. As it turned out, the four men lost in the surf of Kauai were the only deaths; all those on Kure survived the 68 days of deprivation on the small atoll.

Coxswain William Halford was awarded a Medal of Honor (which at the time could be awarded for peacetime valor):

“War Department, General Orders No. 169 (February 8, 1872). The President of the United States, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Coxswain William Halford, United States Navy, for gallant and heroic conduct in line of his profession as Coxswain serving on USS Saginaw. Coxswain Halford was sole survivor of the boat’s crew sent to the Sandwich Islands for assistance after the wreck of the Saginaw, 1 October 1870. Promoted to Acting Gunner.”

Halford continued to serve in the U.S. Navy until he reached mandatory retirement age of 62 in 1903. However, during World War I, the need for experienced men in the rapidly expanded Navy resulted in him being recalled to active duty, at age 77, on 1 July 1918, with a rank of Acting Lieutenant. He was still serving when he died on 7 February 1919 and was buried at Mare Island Navy Yard. The destroyer USS Halford (DD-480) was named in his honor. Commissioned in April 1943, Halford earned 13 battle stars in Pacific combat, and had the distinction of being one of only three Fletcher-class destroyers to be built with a cruiser catapult (and scout plane) in lieu of the after torpedo bank and No. 3 5-inch gun, although this was quickly determined to be impractical and was removed. Halford was decommissioned in May 1946.

CDR Sicard (USNA 1855) continued to serve in the U.S. Navy, having seen extensive combat on the Mississippi River at New Orleans, Vicksburg, and other locations during the Civil War. He was promoted to captain in 1881 and served as the Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance from 1881 to 1890. He was promoted to commodore in 1894 and rear admiral in 1897 in command of the North Atlantic Squadron. Illness forced him ashore at the outbreak of the Spanish American War, but as the director of the Board of Strategy he played a significant part in the planning and conduct of the war. He retired in September 1898 and died in September 1900. The destroyer USS Sicard (DD-346) was named in his honor, serving from 1920 to 1945, with an eventful career in the Far East (Great Japanese earthquake of 1923 and the onset of the Chinese Civil War) and served as a minelayer during World War II, before being decommissioned in November 1945.

The Saginaw’s gig survived the fatal landing on Kauai. It was transported to Honolulu where it was auctioned off to benefit the crew of Saginaw. The purchasers immediately donated it back to the Navy. In 1889 it arrived at the U.S. Naval Academy via service at Mare Island and the Sloop-of-War Jamestown. In the 1930s, the superintendent of the Naval Academy, Rear Admiral David F. Sellers (who had reverted to his permanent two-star rank after concluding his tour as the four-star Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet) sought to have the gig preserved as a permanent memorial to inspire midshipmen by its legacy of survival and heroism. Everything was in place when Sellers retired, but his successors chose not to follow up, and it wound up crammed in a stairwell of the natatorium. In 1946, the head of the Department of Physical Training wanted it out of his building and in 1947 it was given to the Curator of the Navy (which today is me). After a period in storage, in 1954 it was loaned to the City of Saginaw, Michigan, where it was displayed in various locations over the years (including the water treatment plant) before the Saginaw County Historical Museum asked to return it to the Navy in 2015, where it is now in the custody of the Naval History and Heritage Command, where it is being conserved and will be displayed in a suitable location befitting its record of “devotion and gallantry,” as CDR Sicard said.

In 2003, an underwater archaeology expedition by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA) located the wreck sites of both Saginaw and Geldtanes in what is now Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument.

(Sources: “The Loss of USS Saginaw” by Jeffery Bowdoin, NHHC Curator Branch Head, in The Sextant blog at usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.mil, posted December 2020. NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS) entry for Saginaw at history.navy.mil).

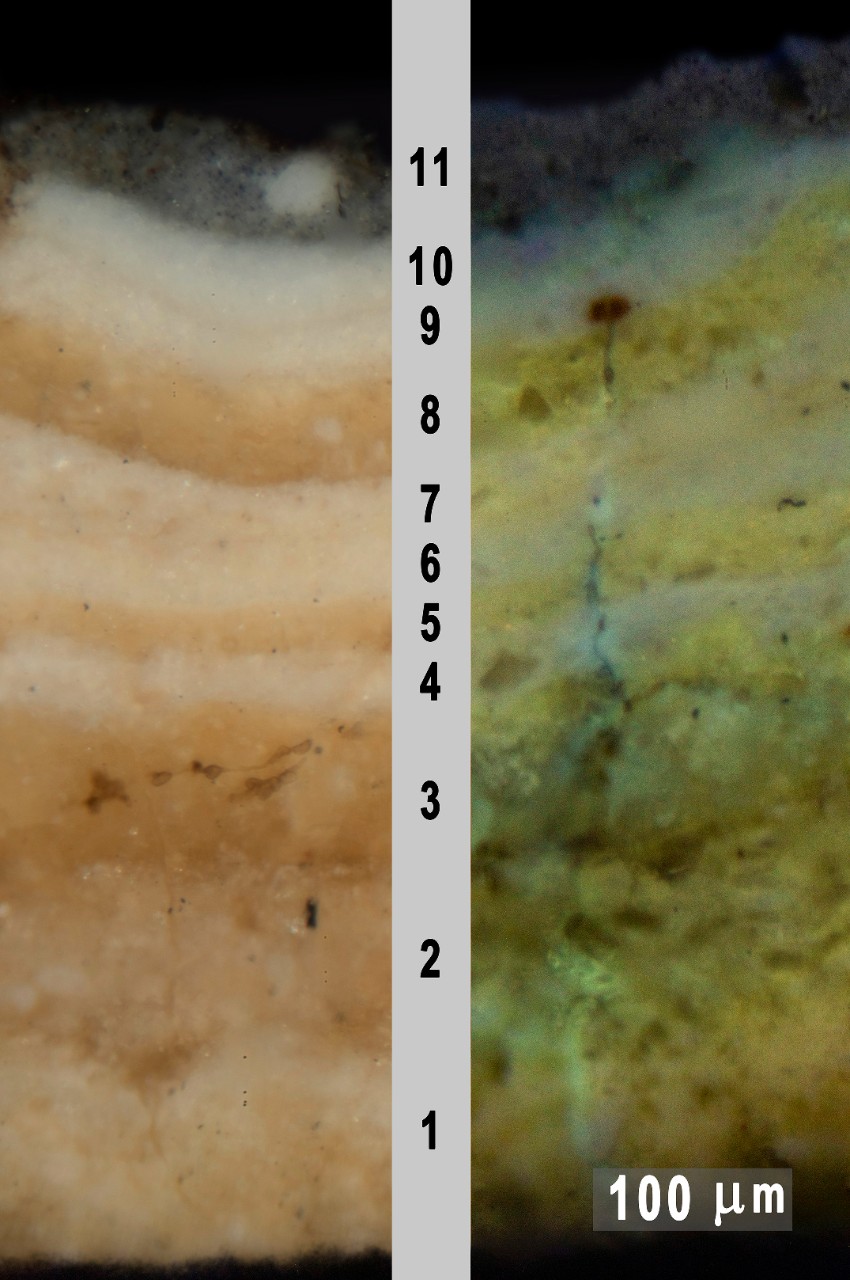

Paint cross-section from the Saginaw gig, viewed with visible light (left) and UV fluorescence (right). The nearly dozen layers the gig received during its service are being analyzed by conservators to determine the best course of conservation treatment.