Welcome to Navy History Matters—our biweekly compilation of articles, commentaries, and blogs related to history and heritage. Every other week, we’ll gather the top-interest items from a variety of media and social media sources that link to related content at NHHC’s website, your authoritative source for Navy history.

Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Victory in Europe

On May 8, 1945, millions across the world celebrated Germany’s unconditional surrender to the Allies and rejoiced in the defeat of the German war machine. Designated by the United States and Great Britain as Victory in Europe (V-E) Day, it was the day that German troops throughout Europe finally laid down their arms, ending six years of unprecedented bloodshed. Leading up to the surrender, in the spring of 1945, Germany’s situation was dire, and they appeared on the verge of defeat, but exactly when German leaders would admit it remained unknown. Furthermore, on April 30, 1945, the Führer, Adolf Hitler, who had touted a thousand-year Greater Germany, killed himself in his command bunker in Berlin. Hitler’s mistress, Eva Braun, and a number of close followers also joined him in death. Before Hitler took his own life, he named Grossadmiral Karl Doenitz, commander in chief of the German Kriegsmarine (navy), as his successor.

Facing overwhelming odds, Doenitz’s main goal in the waning days of the European war was to ensure maritime evacuation—from the Baltic provinces to western Germany—of as many German troops and civilians as possible before the last remaining German-held ports fell into the hands of the Soviets. On May 5, a day after German troops surrendered to the British army in the Netherlands, Denmark, and northwestern Germany, Doenitz contacted Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, in France to negotiate Germany’s surrender. From his headquarters in the northern German port city of Flensburg, Doenitz tried to draw out negotiations as long as possible in order to continue the withdrawal in the east, but Eisenhower would not tolerate the Germans stalling their inevitable surrender. On May 7, German armed forces Chief of Operations Generaloberst Alfred Jodl signed the instrument of unconditional surrender in Rheims. The surrender ceremony was repeated the following day with the Soviets in Berlin by Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel as the German signatory.

As during World War I, the U.S. Navy’s contribution to the war effort in the European theater of operations was significant. Its main mission was to ensure that sufficient personnel and material reached European and northern African shores. From early 1942 through May 1943, the Battle of the Atlantic had mixed success for the Allies. Enormous quantities of supplies helped sustain Great Britain and the Soviets, and a combined U.S.-Anglo force successfully completed an amphibious assault that secured North Africa between November 1942 and the spring of 1943. However, thousands of ships and millions of tons of supplies and raw materials were sent to the bottom of the ocean as German U-boats sank more shipping tonnage than the Americans and British could manufacture. Increasing industrial capacity, new technologies, improved intelligence, better training, and updated organizational approaches helped turn the tide of the European war. Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Ernest J. King’s creation of Tenth Fleet, dedicated to antisubmarine warfare, also was a major contributor. In addition, air attacks on German infrastructure and the Allies’ recapture of French ports in 1944 further reduced the U-boat threat. For example, during the first four months of 1945, Germany lost 153 submarines, compared to only 85 in all of 1942. However, U-boats remained a danger until the very end of the war. Just before surrendering, Germany made a last-ditch effort to attack shipping off the eastern seaboard of the United States. On the evening of May 5, German submarine U-853 sank American merchant ship/collier Black Point just four miles from Block Island, Rhode Island. However, the enemy submarine failed to make it out of the area quickly enough and was sunk several hours later.

Although V-E Day had arrived, the war in the Pacific still raged on. Planners envisioned sending a steady flow of personnel from the European to the Pacific theater during the second half of 1945 to force a Japanese surrender in, hopefully, 1946. Some 400,000 Soldiers were projected to leave Europe and the Mediterranean, with most expected to arrive by late September. Another 800,000 were set to deploy from the United States. Fortunately, only about a third of them reached the Pacific. Operation Downfall, the planned invasion, occupation, and unconditional surrender of Japan, would have required at least an estimated 1.7 million U.S. troops. It was projected that the entire operation could lead to 400,000 to 800,000 U.S. killed. Japan would have potentially suffered 5 to 10 million deaths, wiping out most of its population. After President Harry S. Truman made the decision to drop two atomic bombs—on Hiroshima on Aug. 6 and on Nagasaki on Aug. 9—Emperor Michinomiya Hirohito announced to the Japanese people on Aug. 14 that Japan had agreed to surrender unconditionally. On Sept. 2, the instrument of surrender was signed by representatives of the Allied and Japanese governments onboard USS Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay. World War II was finally over.

In the aftermath of the war, celebrations erupted across the United States, Europe, and Asia; however, it was just the beginning of even more complex problems throughout the world. Hugh swaths of Europe and Asia and been reduced to ruins, borders were redrawn, and the massive effort to rebuild had just begun. Allied forces now were the occupiers, taking control of Germany, Japan, and much of the territory they had formally occupied. In addition, efforts were made to permanently dismantle the future war-making capabilities of those countries. Former leadership was removed or prosecuted. War crimes’ trials took place in Europe and Asia, leading to executions or lengthy prison sentences. Millions of German and Japanese citizens were forcibly expelled from territories they had previously called home. Allied occupations and United Nations (UN) decisions led to long-lasting problems, including the tensions created with the formation of East and West Germany, and the creation of North and South Korea that ultimately led to the Korean War. The UN partition plan for Palestine paved the way for Israel to declare its independence in 1948, marking the beginning of continuing Arab-Israeli conflicts. Growing tensions between Western powers and the Soviet Union developed into the decades-long Cold War. The development and proliferation of nuclear weapons raised the very real specter of an unimaginable World War III if common ground could not be found on the nuclear option. Although World War II was the biggest event of the 20th century, its aftermath continues to affect the world as we know it to this day.

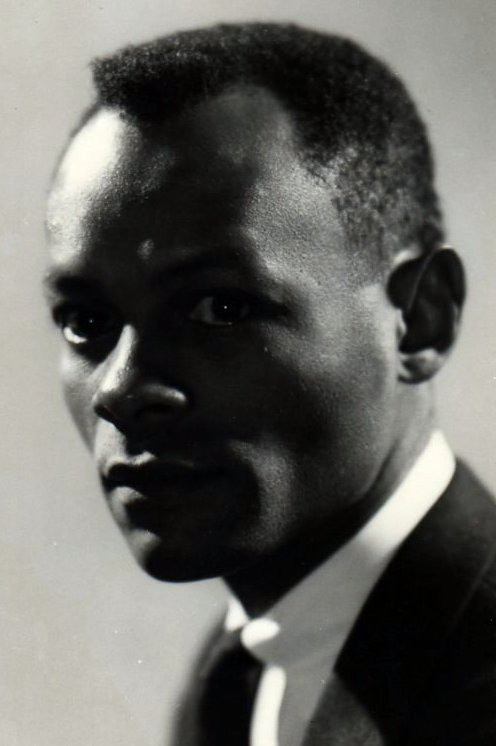

Remembering Artist Hughie Lee-Smith

Throughout the history of the U.S. Navy, African Americans have distinguished themselves ashore, on ships, in aircraft, and on submarines through times of peace and conflict. One such individual was artist Hughie Lee-Smith. Drafted into the Navy during World War II, Lee-Smith reported for active duty on Jan. 20, 1944, and spent the next 19 months serving as an official painter at Camp Robert Smalls, an isolated camp within the perimeter of Naval Station Great Lakes, Illinois, that trained Black recruits. Educated at the Cleveland Institute of Art, Lee-Smith often worked on art pieces for the recreation building with two other African American seamen, Edsel Cramer and Isaiah Williams, who also received an art education before the war. Lee-Smith’s first solo exhibition was held at Chicago’s South Side Community Art Center in 1945. Among the paintings displayed, the exhibition featured works inspired by Lee-Smith’s time in the Navy, including one titled Machinist Mate, World War I. Following the war, the collection of murals at Camp Robert Smalls were donated to the South Side gallery.

After Lee-Smith was released from active duty, he went back to school utilizing the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (commonly known today as the G.I. Bill), attending Wayne State University in Detroit. He earned a bachelor’s degree in art education in 1953, and the same year, he received an award for painting from the Detroit Institute of Arts. Over the next decade, his artwork reflected themes of isolation and desolation in an urban environment. However, he never forgot his service in the Navy.

In 1971, he began working on commission for the Navy as an artist. His first commission was a portrait of Rear Adm. Samuel L. Gravely, followed by another painting featuring Black Sailors at the prow of George Washington’s boat crossing the Delaware. Both of these works were incorporated into the official Navy art collection held at the Washington Navy Yard. Although he did not work as a full-time artist for the Navy as a civilian, Lee-Smith continued to accept commissions from the Navy while he exhibited his own work at commercial galleries and museums. In 1977, the Navy’s first African American officers organized their first reunion, at which they adopted the name “The Golden Thirteen.” Lee-Smith attended the reunion and later completed artwork for the event to add to the Navy’s collections.

In 1999, Lee-Smith passed away at the age of 83. For more on the life of Hughie Lee-Smith by Communications and Outreach Division’s Katie Engel, visit NHHC’s website.

Oldest Carrier in Active Service: USS Nimitz (CVN-68)

On May 3, 1975, USS Nimitz (CVN-68) was commissioned at Naval Station Norfolk, Virginia. “Only America can make a machine like this,” said President Gerald R. Ford at its commissioning ceremony. “There is nothing like it in the world.” The supercarrier is 1,092 feet in length and can accommodate a crew of 428 officers and more than 4,000 crewmembers. Nimitz is capable of supporting 85–100 aircraft. The ship, first in class, is named to honor Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who as commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas led American forces to victory over the Japanese Empire during World War II. He was one of only four flag officers to attain the rank of five-star fleet admiral and served as Chief of Naval Operations after the war (1945–47).

After Nimitz was commissioned, it deployed to the Mediterranean twice, in 1976 and 1977. On Sept. 10, 1979, it was dispatched to the Indian Ocean as tensions heightened when Iran took 52 Americans hostage at the U.S. embassy in Tehran. Four months later, Operation Evening Light (also known as Operation Eagle Claw) was launched from Nimitz in an attempt to rescue the hostages. However, the rescue attempt was aborted in the Iranian desert when the number of operational helicopters fell below the minimum needed to complete the rescue.

In October 1988, Nimitz began operating in the North Arabian Sea in support of Operation Earnest Will, and in February 1991, it relieved USS Ranger (CV-61) in support of Operation Desert Storm. Two years later, it returned to the Arabian Gulf as part of Operation Southern Watch. On Sept. 1, 1997, Nimitz set course for an around-the-world cruise, where it again was called upon to support Operation Southern Watch and various UN initiatives. In 2003, 2005, 2009, and 2013, Nimitz deployed in support of Operations Enduring and Iraqi Freedom. In 2014, after participating in a multi-national exercise, the first experimental F-35C Lightning II to land on an aircraft carrier was recovered aboard Nimitz to begin two-weeks of testing. After the deployment, Nimitz underwent a 16-month maintenance cycle. In June 2017, Nimitz was underway for its next scheduled deployment. During the deployment, F/A-18s from Nimitz played an important role in the Battle of Tal Afar, providing precision air support for advancing Iraqi soldiers against ISIS in Iraq and Syria. Afterwards, Nimitz spent 10 months in overhaul. After several months of inactivity due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Nimitz conducted several deployments to Somalia, the Arabian Gulf, Singapore, Guam, and South Korea. On April 22, 2023, Nimitz logged its 350,000th arrested landing.

In popular culture, the 1980s film The Final Countdown, an alternate history science fiction film about an aircraft carrier that travels through time to the day before the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, was set and filmed aboard Nimitz. The aircraft carrier and the crew onboard have also been the subject of several television shows that were oriented toward teaching children about the ship and life aboard it. In 2005, PBS aired a 10-part series documenting its deployment to the Arabian Gulf.

Nimitz, which is homeported at Naval Base Kitsap, Washington, is the oldest American aircraft carrier in active service. It is scheduled to be decommissioned sometime next year as part of the approximate 50-year lifespan for Nimitz-class carriers.

Today in Naval History—Fall of Saigon

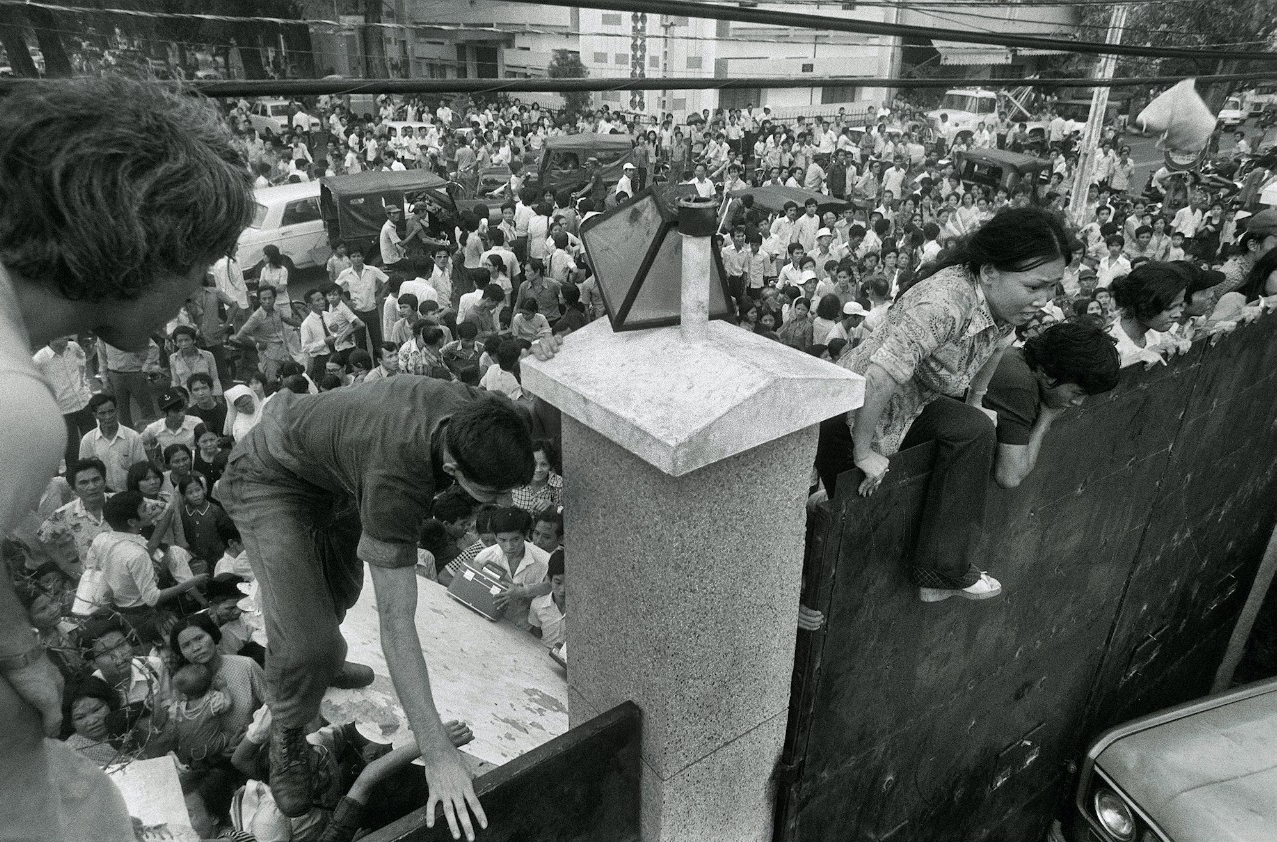

On April 30, 1975, the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese army, effectively ending the Vietnam War. In anticipation of the fall of Saigon, Task Force 76 (TF-76) received the order the previous day to execute Operation Frequent Wind—the evacuation of U.S. personnel and Vietnamese who might suffer as a result of their past affiliation to the allied effort. Just after noon on April 29, from the Vung Tau Peninsula, USS Hancock (CV-19) launched the first helicopter wave, and over the next two hours, helicopters landed at the primary landing zone at the U.S. Defense Attaché Office compound in Saigon. Once the ground security force (2nd Battalion, 4th Marines) had established a defensive cordon, TF-76 helicopters began lifting out thousands of American, Vietnamese, and third-country nationals. The process was fairly orderly, and by 9 p.m., the entire group of 5,000 evacuees had been cleared from the site. The Marines holding the perimeter soon followed.

The situation was much less stable at the U.S. embassy. There, several hundred prospective evacuees were joined by thousands more who climbed fences and pressed the Marine guard in their desperate attempt to flee the city. Marine and Air Force helicopters, flying at night through ground fire over Saigon and the surrounding area, had to pick up evacuees from dangerously constricted landing zones at the embassy, one atop the building itself. Despite the challenges, by 5 a.m. on April 30, U.S. Ambassador Graham Martin and 2,100 evacuees had been rescued from the approaching Communist forces. Only two hours after the last Marine security force element was extracted from the embassy, North Vietnamese tanks crashed through the gates of the nearby Presidential Palace. At the cost of two Marines killed in an earlier shelling of the Defense Attaché Office and two helicopter crews lost at sea, TF-76 rescued more than 7,000 Americans and Vietnamese.

Meanwhile, out at sea, the initial trickle of evacuees from Saigon soon became a flood of desperate refugees. Vietnamese air force aircraft, loaded with air crews and their families, made up part of the last remnants of the South Vietnamese military. These incoming helicopters (mostly low on fuel) complicated the landing and takeoff of U.S. Marine and Air Force helicopters shuttling evacuees. Ships of the American task force recovered 41 Vietnamese aircraft; however, another 54 were pushed over the side to make room on the deck or ditched by their frantic crews. Naval small craft rescued many Vietnamese from sinking helicopters, but some did not survive the ordeal. The aerial exodus was paralleled by an outgoing tide of junks, sampans, and small craft of all types bearing a large number of the fleeing population. Military Sealift Command (MSC) tugs Harumi, Chitose Maru, Osceola, Shibaura Maru, and Asiatic Stamina pulled barges filled with people from the Saigon port out to the MSC flotilla. There, the refugees were embarked, registered, inspected for weapons, and given a medical exam. Having learned from the earlier operations, the MSC crews and Marine security personnel processed the new arrivals with relative efficiency. The Navy eventually transferred all Vietnamese refugees taken on board naval vessels to the MSC ships. Another large contingent of Vietnamese was carried to safety by a flotilla of 26 Vietnamese navy and other vessels. These ships concentrated off Son Island southwest of Vung Tau with 30,000 sailors, their families, and other civilians on board.

On the afternoon of April 30, TF-76 and the MSC group moved away from the coast, all the while picking up more seaborne refugees. This effort continued the following day. Finally, when the tide of refugees ceased on the evening of May 2, TF-76 carrying 6,000 passengers, the MSC flotilla with 44,000 refugees, and the Vietnamese navy group steamed for reception centers in the Philippines and Guam. Thus ended the U.S. Navy’s role in the decades-long American effort to aid the Republic of Vietnam in its desperate fight for survival.