Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

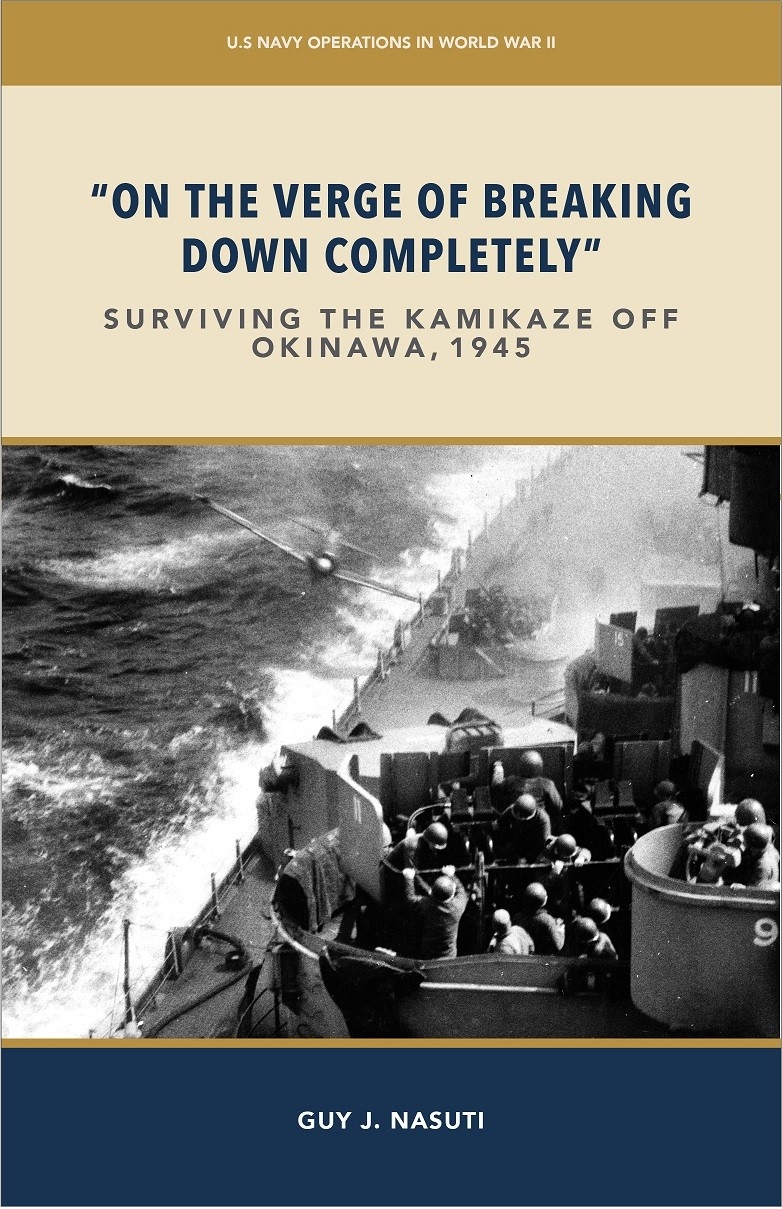

Surviving the Kamikaze off Okinawa

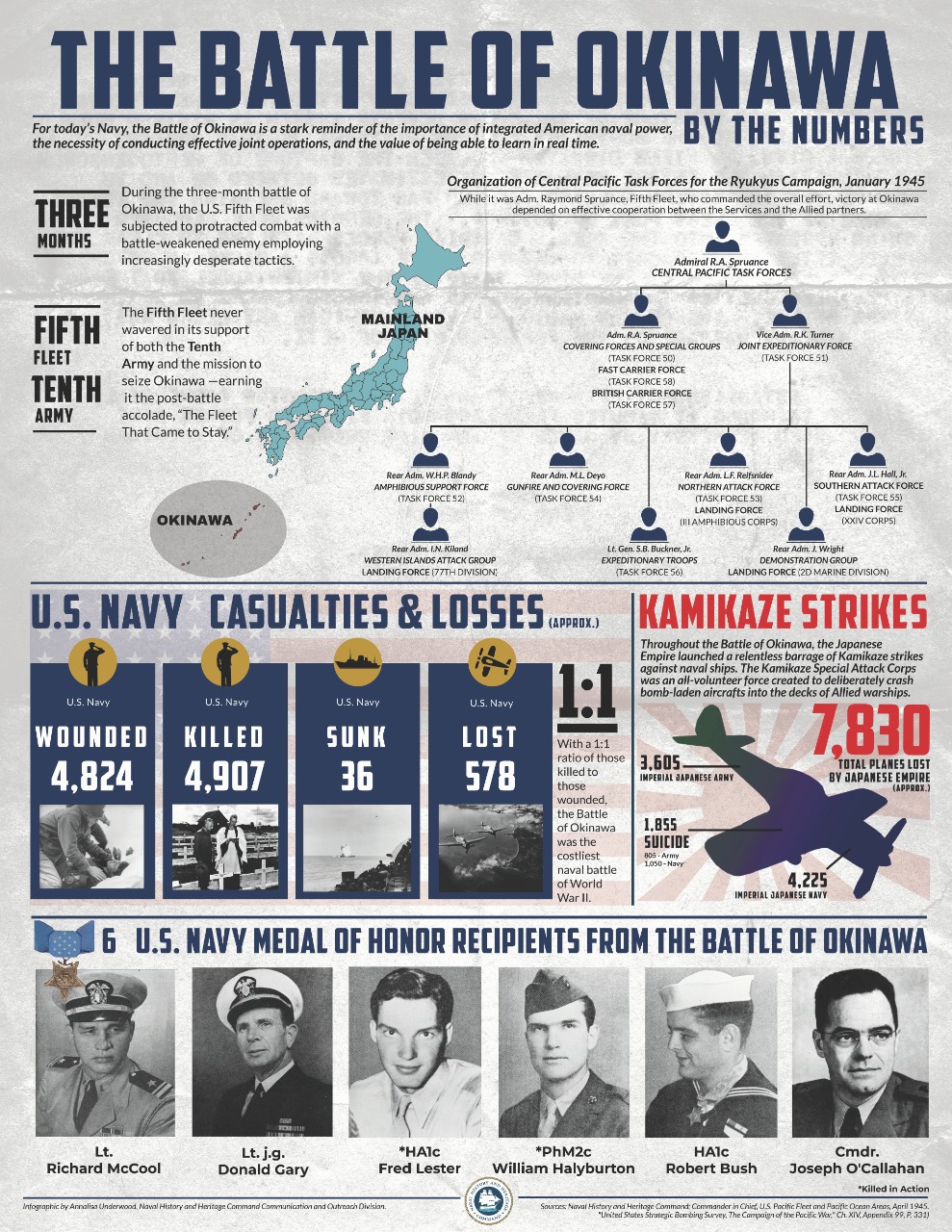

During the Battle of Okinawa, American Sailors confronted their most destructive enemy of the Pacific War—the kamikazes of the Imperial Japanese Special Attack Corps. Over the course of what quickly became the deadliest fight ever fought by the U.S. Navy, American naval officers and their crews developed new tactics to counter the brutal onslaught of a suicidal enemy whose sole purpose was to demoralize the U.S. fleet and inflict as many casualties as possible. With hopes for a negotiated peace diminishing, Japan’s leaders viewed kamikaze attacks as their last hope of preventing U.S. forces from reaching the home islands and compelling Japan’s unconditional surrender. For the first time in World War II, the number of U.S. Sailors killed in action was greater than the number of American Soldiers or Marines who died fighting during a sustained engagement.

Recently, Naval History and Heritage Command published a new book, “On the Verge of Breaking Down Completely”: Surviving the Kamikaze off Okinawa, 1945. Written by NHHC Historian Guy J. Nasuti, it is available for free as a 508-compliant PDF on NHHC’s website. The publication is part of the U.S. Navy Operations in World War II commemorative series. It draws on the accounts of enlisted Sailors and sheds new light on the desperate struggle off Okinawa. The book provides fresh insight into the terrifying ordeal American Sailors underwent during the relentless assault of suicide attacks. Ultimately, their tenacity and ability to adapt in order to survive and win should serve as enduring inspiration to those serving in the U.S. Navy today.

On Oct. 25, 1944, during the Battle off Samar in the Philippines, a Japanese Mitsubishi fighter plane purposely crashed onto the flight deck of escort carrier St. Lo (CVE-63), which subsequently was lost. It was the first major Allied warship sunk by a kamikaze during the war. The attack ripped St. Lo apart, and it sank in less than 20 minutes, killing 114 of its crew. It also marked a new milestone in an already brutal war. A more organized series of kamikaze attacks would come. As the Allies closed in on Japan, the enemy desperately sought a strategy to prevent the Allies from invading the home islands and force a negotiated settlement on their terms rather than unconditional surrender. To pursue their goals, Japanese officers began to discuss launching suicide attacks against Allied ships as early as June 1944. By year’s end, the early stages of massed kamikaze attacks began to take shape. Japanese leadership embraced the strategy to delay a deteriorating combat situation and began to convert all armament production to special attack weapons.

Just prior to securing the volcanic island of Iwo Jima, the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet began steaming for Okinawa to stage for the eventual invasion of Japan. In response, Japanese strategists hurriedly planned to counter the American fleet. The overall plan at the onset of the Okinawa battle (termed Operation Kikusui, or “Floating Chrysanthemums”) involved 10 massed kamikaze attacks between the end of March and June 1945. In the attacks, about 9,400 aircraft headed toward the U.S. fleet, although not all were kamikazes. Over the course of the nearly three-month battle for Okinawa, 1,840 Japanese sorties were suicide missions, in which 960 participating aircraft were destroyed, either by antiaircraft fire, combat air patrols, or striking their targets.

In an effort to protect the larger ships of the task force, the U.S. Navy established a ring of 15 radar picket stations around Okinawa. Manned by a destroyer and smaller supporting craft, the picket stations quickly bore the brunt of mass air attacks, with no fewer than 10 destroyer and escort vessels sunk and another 32 damaged to varying degrees by the end of the Okinawa battle. Although defensive measures created by radar pickets proved valuable in the early stages of the battle, the Japanese were soon able to exploit the situation. Their attacks became an effort to knock out radar coverage and allow successive waves of kamikazes to engage the larger ships (mostly aircraft carriers) of the U.S. fleet undetected. Sailors on picket stations were forced to remain at their battle stations for long hours and were often recalled to general quarters several times throughout the day and night. Enduring daily suicidal attacks took a tremendous toll on crew morale and their ability to make quick decisions. Frequently, combat-fatigued Sailors made decisions that led to accidents and a breakdown of combat readiness. In addition, the psychological trauma inflicted on American Sailors would haunt them for years to come.

Operation Dragoon: The Invasion of Southern France

On Aug. 15, 1944, Operation Dragoon (formally code-named Anvil), the Allied invasion of southern France, began. Originally, the operation was planned to run concurrently with Operation Overlord. However, it was viewed skeptically by the British, primarily by Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who maintained a cautious attitude toward any landing operations in German-occupied France and also felt that any Allied effort in the Mediterranean theater should be applied to operations in Italy or the Balkans. The first time the operation was discussed was when President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill, and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin met in Tehran in 1943. At the conference, all agreed to support the concurrent Overlord and Anvil operations; however, Anvil was then postponed due to Churchill’s objections. Although the consensus surrounding Anvil quickly vanished, Army Gen. Jacob Devers, who was in charge of planning the operation, continued to prepare despite its postponement. After the successful landings on Normandy, the Allies assessed that they had enough shipping capacity to undertake another amphibious operation in France. Hence, Anvil was reborn. It was renamed Dragoon due to security concerns. The operation was set to commence on Aug. 15. It called for the American and French armies to land just east of Marseille and Toulon and capture them. The capture of the cities would ultimately increase Allied supply capacity on the French mainland.

On D-Day, the landings of the Western Naval Task Force, led by U.S. Eighth Fleet’s Vice Adm. Henry K. Hewitt and the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet, went well for the Allies. The task force also included a number of French and Polish combatants. To soften the battlefield, and in conjunction with naval shore bombardment, Allied air forces had begun bombing port facilities, coastal fortifications, bridges, and communications nodes in proximity of the projected landing areas beginning at the end of June. When the Allies initially landed about 94,000 troops, they were barely opposed. The Germans were already demoralized and disorganized by aerial and naval bombardment and, except for one particular strongpoint that was eventually neutralized by B-24 Liberator air strikes, put up little resistance. By the evening of Aug. 17, the surviving German forces were in full retreat up the Rhone Valley, continually harassed by the French resistance. The First French Army subsequently surrounded Marseille and Toulon. Both cities fell to the French on Aug. 28, a month earlier than was originally planned. The U.S. Seventh Army attempted to cut off the German Nineteenth Army near Montélimar, but they failed to encircle the retreating Germans. However, the battle left the Germans badly damaged and in full retreat toward the Franco-German border. The operation formally ended in mid-September after the Seventh Army made contact with Gen. George Patton’s Third Army advancing from the west.

Although Operation Dragoon was deemed a success, Churchill continued to ridicule the operation throughout the war and even in his postwar memoirs. He cited it as the reason Stalin was able to amass influence in the Balkans and Eastern Europe. However, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower noted, “There was no development of that period which added more decisively to our advantages . . . than did this secondary attack coming up the Rhone Valley.” Despite disagreements about the operation, it was soundly conceived based on previous amphibious operations. Although British concerns about the Italian theater limited the number of Allied ground troops, the operation achieved all of its tactical and strategic objectives in a minimum amount of time.

Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

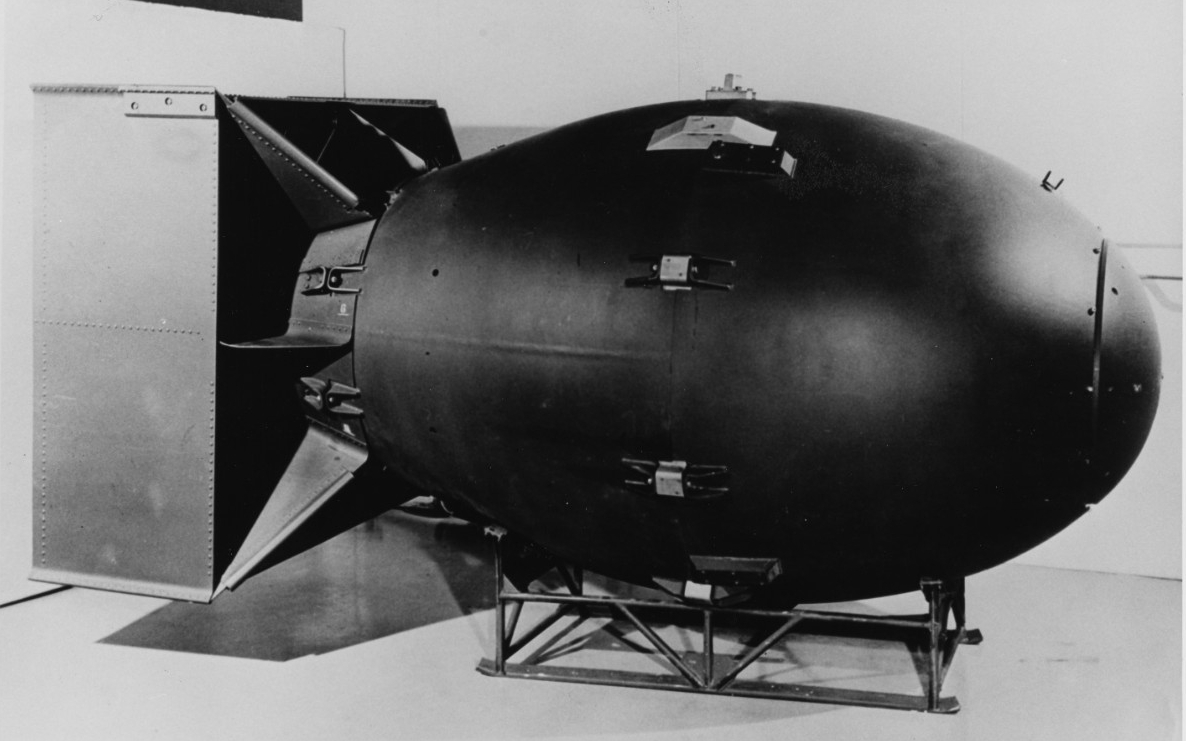

On Aug. 9, 1945, an American B-29 bomber dropped a second atomic bomb, “Fat Man,” on Nagasaki, Japan. The first atomic bomb, “Little Boy,” had been dropped on Hiroshima on Aug. 6. It was the first time atomic bombs were used in warfare. In both cases, Navy personnel participated in the missions as weaponeers. In the aftermath, Japan’s Emperor Hirohito called an imperial conference of all high-level advisers to discuss an unconditional surrender. Although there were disagreements, Emperor Hirohito made the decision to surrender on Aug. 10. On Aug. 14, Hirohito’s surrender announcement to the Japanese nation was recorded. Despite an attempted last-minute coup by radical militarists, the message was broadcasted, and Japan agreed to surrender unconditionally. The instrument of surrender was signed by representatives of the Allied and Japanese governments on Sept. 2 onboard USS Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay, ending World War II.

The development of the atomic bomb was a long time in the making. Even before the outbreak of the war in 1939, a group of American scientists (many of them refugees from fascist regimes in Europe) became concerned with nuclear weapons research being conducted in Germany. In 1940—fearing that Adolph Hitler had the atomic bomb and was prepared to use it—the U.S. government began funding its own atomic weapons development program. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was tasked with spearheading the construction of the vast facilities necessary for the top-secret program (code-named Manhattan Project). Over the next several years, the program’s scientists worked on producing the key materials for nuclear fission (uranium and plutonium). They sent the materials to Los Alamos, New Mexico, where a team led by J. Robert Oppenheimer worked to turn the materials into an atomic bomb. On the morning of July 16, 1945, the Manhattan Project held its first successful test of an atomic device (a plutonium bomb) at the Trinity test site at Alamogordo, New Mexico.

By the time the Trinity test was completed, Germany had already surrendered; however, Japan had vowed to fight to the bitter end. By the time of the ferocious battles at Iwo Jima and Okinawa that cost the lives of thousands of U.S. service members, the American public had grown weary of the war and wanted it to end. When President Harry S. Truman asked his top advisors what they believed the cost of Allied and Japanese lives would be in the invasion of Japan (code-named Operation Downfall), some estimated it could be up to 1 million. In order to avoid such a high number of American casualties, President Truman decided to make the tough decision and drop the atomic bomb. For more on the U.S. Navy and the atomic bomb, read H-Gram 079 by Director Sam Cox at NHHC’s website.

Today in Naval History—Fort McHenry Commissioned

On Aug. 8, 1987, USS Fort McHenry (LSD-43) was commissioned at Lockheed Shipyard in Seattle. The Whidbey Island–class dock landing ship was named for Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Maryland. It’s the 1814 defense of the fort during the War of 1812 that inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem that later became the lyrics for the Star Spangled Banner. After it was commissioned, Fort McHenry was homeported in San Diego until 1995, when it replaced USS San Bernardino (LST-1189) as a forward-deployed ship based in Sasebo, Japan.

During its maiden voyage in 1988 to the Western Pacific, Fort McHenry was part of an amphibious ready group that participated in exercises Cobra Gold-88, Valiant Usher 88-6, and Valiant Blitz 89-1. The following year, Fort McHenry assisted the Coast Guard in the cleanup of the Exxon Valdez oil spill off Alaska. In recognition of that service, the ship received the Meritorious Unit Commendation and the Coast Guard Special Operations Service Ribbon. Over the next few decades, Fort McHenry would shift its homeport and deploy several more times, supporting Operations Desert Shield/Desert Storm, Vigilant Warrior, and Enduring Freedom. Its crews provided humanitarian assistance domestically, such as oil spill cleanup in the Prince William Sound, and internationally, supporting disaster relief efforts in East Timor in 2001 and in the Philippines and Indonesia in 2004. The ship also participated in activities marking the 60th Anniversary of the Battle of Iwo Jima on March 12, 2005, before returning to Sasebo about two weeks later.

Fort McHenry, as part of the Bataan (LHD-5) amphibious relief mission, participated in Operation Unified Response, providing humanitarian support to civil authorities in order to stabilize and improve the situation in Haiti following an epic 7.0 magnitude earthquake on Jan. 12, 2010. The ship continually stayed on station during the crisis before it departed Haitian waters on March 11.

In conjunction with the Emerald Isle Classic football game between the University of Notre Dame and the U.S. Naval Academy played in Dublin, Ireland, Fort McHenry made a port call at the Irish capital from Aug. 31—Sept. 3, 2012. While in port, the ship was visited by Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan Greenert; U.S. Army Gen. Martin E. Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; Ireland's Prime Minister Enda Kenny; Daniel Rooney, U.S. ambassador to Ireland; and Irish navy Commodore Mark Mellett.

In January 2015, the Iwo Jima Amphibious Readiness Group, consisting of Iwo Jima (LHD-7) and Fort McHenry with embarked units of the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit, were on station in the Red Sea in order to respond to any non-combatant evacuation operation contingencies for U.S. citizens resulting from the civil war between Yemeni government forces and Shiite Houthi rebels.

The ship’s final deployment was part of the USS Kearsarge (LHD-3) amphibious ready group and concluded in July 2019. While deployed to the European, African, and the Middle Eastern areas of operations, Fort McHenry, along with embarked Marines, conducted maritime security operations and provided a forward naval presence in the critical regions. During the deployment, Fort McHenry Sailors conducted a burial at sea for the remains of 34 veterans and two military spouses, a passing exercise with Egyptian navy ships in the northern Arabian Sea, and more than 15 strait transits and port visits to Romania, the United Arab Emirates, Germany, and Latvia. The ship capped off the deployment by participating in exercise Baltic Operations 2019. Fort McHenry decommissioned at Naval Station Mayport, Florida, on March 27, 2021.