Frigate Chesapeake

As one of the first six frigates constructed specifically for the U.S. Navy, the frigate Chesapeake was launched in 1799. During a battle with HMS Shannon during the War of 1812, Captain James Lawrence uttered the immortal words, “Don’t give up the ship.” Painting, oil on canvas; by Frank Muller; circa, 1910; framed dimensions 32H X 49W. Accession #: 44-006-F.

The frigate Chesapeake was launched on 2 December 1799 at the Gosport Navy Yard, Virginia, and commissioned on 22 May 1800 with Captain Samuel Barron in command. The ship was one of six frigates authorized by Congress with passage of the Naval Act of 1794. During the Quasi-War with France, French privateers regularly ransacked American ships, claiming their goods as prizes and then would scuttle or sail the captured ships to French ports. As early as 28 May 1798, more than a year before Chesapeake was launched, President John Adams issued instructions to his Navy commanders, stating they “are hereby authorized, instructed and directed to subdue, seize, and take any armed vessels of the French Republic.” On 6 June 1800, Chesapeake set sail from Norfolk, Virginia, to patrol for enemy cruisers and privateers around the islands of St. Kitts, St. Thomas, and St. Bartholomew, but Chesapeake did not have any interaction, initially, with any privateers. In early January 1801, Chesapeake gave chase for more than 50 hours on French privateer La Jeune Creole. The French ship had jettisoned six of her sixteen guns in an attempt to outrun the American frigate, but she was eventually captured. Barron placed one of his ship’s lieutenants and a small crew on board La Jeune Creole, and they sailed her to Norfolk, arriving on 15 January 1801. The next month, a peace treaty with France was ratified, thus Chesapeake set sail for Norfolk where she was placed in ordinary for most of the remainder of the year.

On 27 April 1802, Chesapeake was readied for departure after Barbary powers continued to prey on merchantmen. During the spring of 1802, Commodore Thomas Truxtun was placed in command of Chesapeake. His squadron consisted of the 32-gun light frigate Essex and the 36-gun Philadelphia, who were in the Mediterranean at the time. He also had at his disposal the 36-gun Constellation, 28-gun Adams, 36-gun New York, 28-gun John Adams, and the 12-gun Enterprise. Truxtun demanded a captain for his flagship, but Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith refused to comply, and ultimately replaced Truxtun as commander of Chesapeake with Captain Richard V. Morris. Four days after Chesapeake set sail for Gibraltar, she was met with foul weather that damaged the ship’s mast spars and rigging. It took until 26 May for Chesapeake to reach Gibraltar, and after further inspection, it was discovered her mast was rotting and needed to be replaced. The repairs were completed the following month, and for the next year, Chesapeake led the blockade of Tripoli and protected American merchantmen. On 6 April 1803, Chesapeake departed Gibraltar for the U.S, where she was laid up in ordinary. Later, the Secretary of the Navy ordered Commodore James Barron to command the U.S. squadron in the Mediterranean, commissioning Chesapeake as his flag ship.

Tensions began to rise over the violation of American neutrality, and the impressments of Sailors by the Royal Navy. The problem stemmed from British sailors deserting their ships once they hit land, and British commanders, subsequently, replaced the deserters—in most cases by force—with reluctant American Sailors. In June 1807, HMS Melampus was seeking supplies when at least four of her sailors deserted. The sailors went ashore and signed up for duty with American ships, including Chesapeake. Also during the summer of 1807, Chesapeake prepared for patrol duty while at anchor off Hampton Roads. On 22 June, Chesapeake hoisted her sails to look for French ships. The American frigate was tasked with double-duty as a supply ship, of sorts, as she was stocked with provisions that filled every vacant corner of the gallant ship. During the afternoon on the first day of the voyage, HMS Leopard overtook Chesapeake. Leopard sent an officer over to Chesapeake with a message from her commanding officer, Captain Salusbury Humphreys, to muster Chesapeake’s Sailors, so the British could inspect the ranks for deserters. Chesapeake’s commander, Barron, refused on the grounds that only he and his officers had the right to muster American Sailors. After 45 minutes of trading insults back and forth, Leopard fired on Chesapeake. Barron was completely caught off guard, and after a barrage of attacks on his ship, struck her colors, but not before he ordered at least one cannon fired as a symbolic gesture. Three of Chesapeake’s Sailors were killed and another 18 wounded, including Barron. Ultimately, four “supposed” deserters were carted off the American ship before Leopard sailed away.

In wake of the Leopard-Chesapeake incident, Barron received a five-year suspension from the Navy based on court martial findings. The group of fellow officers found Barron showed negligence by not putting the ship in perfect order before they had set sail, failed to see the suspicious movements of Leopard, and showed indecision in his orders. Barron, a lifelong seaman with a family of six, turned to the merchant service to support himself and his loved ones in wake of the findings and ensuing punishment. The command of Chesapeake's squadron was turned over to Commodore Stephen Decatur.

In October 1812, frigate United States and brigantine Argus departed Boston as part of a three-ship squadron as hostilities with Great Britain, once again, came to fruition. Chesapeake, the third ship of the squadron, which was commanded by Captain Samuel Evans, was unable to launch until 17 December due to refitting. While en route to join the squadron, Chesapeake captured two British merchantmen that had left their convoy in South America. Later, on 12 January 1813, the British ship Volunteer was captured bound from Liverpool to Bahia with a considerable amount of dry goods on the ship. Evans placed a crew on the British ship and gave them orders to sail for the United States. The next day, another sail was spotted around 11 a.m. on the horizon. Chesapeake hoisted British colors and boarded the brig Liverpool Hero in an attempt to collect information regarding the remainder of the convoy. Although there was little of value on the ship, Evans decided to use her main mast to replace one of Chesapeake's main top masts that had been destroyed days prior in a storm. After deciding to forgo joining the squadron in an attempt to capture more merchantmen, Evans captured British brig Earl Percy on 5 February bound from Bonavista to Brazil with a cargo of salt. He subsequently decided to assign the British ship as a prize. After two weeks of heavy seas and no enemy contact, Chesapeake sailed for Surinam, where on 7 April, she recaptured the American schooner Valerius that had been taken previously as a prize by the British Navy. After the leaders of Volunteer and Liverpool Hero were paroled and placed on Earl Percy, Chesapeake set sail on 10 April for the United States with about 40 to 50 prisoners arriving in Boston later that month.

After making port in Boston, Secretary of the Navy William Jones sent correspondence to Evans advising him to prepare Chesapeake as soon as possible with little or no cost to the Navy. Evans, who was exhausted from the previous four-month cruise and had a nagging eye injury, requested shore duty. Captain James Lawrence, who had just been placed in command of the New York Navy Yard, was ordered to command Chesapeake. On 18 May 1813, Lawrence arrived in Boston and reluctantly reported for duty to Commodore William Bainbridge. He officially took command of Chesapeake on 20 May 1813. Lawrence assigned Augustus C. Ludlow, who was just 20 years old, as first lieutenant and Midshipmen William S. Cox and Edward J. Ballard as acting lieutenants.

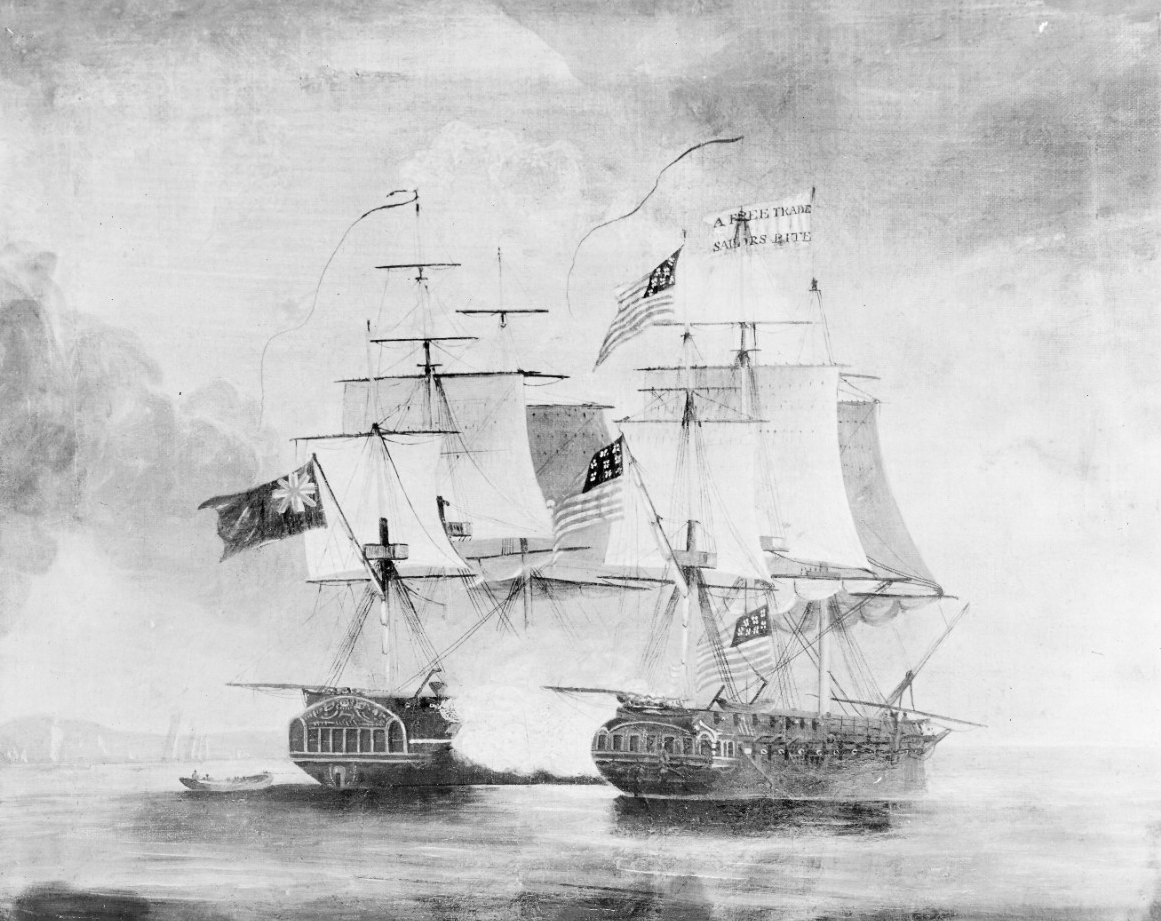

At the end of May 1813, while outside Boston Harbor, British Captain Phillip B.V. Broke, commander of the 38-gun Royal Navy frigate Shannon, climbed on the main rigging of his ship to get a good look at Chesapeake that had not yet set sail. After noting that she was still in preparation, Broke wrote a pointed letter to Lawrence issuing the challenge of a ship duel. Although at the time ship duels were somewhat common, they were clearly against American naval strategic interests. The American Navy was more focused on breaking up and preying on British shipping. Ship duels could lay a ship up for months with repairs, and resulted in a significant reduction of power for the fledging U.S. Navy. Lawrence actually never received the letter before Chesapeake set sail on 1 June. Lawrence, with half of his officers and around one quarter of the crew new to the ship and many of which had not even practiced firing the cannons or small arms, ordered his ship to sail in Shannon’s wake hoisting a banner with the motto, “Free Trade and Sailors Rights.” Broke, who had commanded Shannon for seven years, was a careful and skillful seaman. He was determined to fight Chesapeake outside of Boston Harbor, so they could not receive assistance from the shore. Shannon’s crew were highly experienced and were much more familiar with their ship than the crew of Chesapeake.

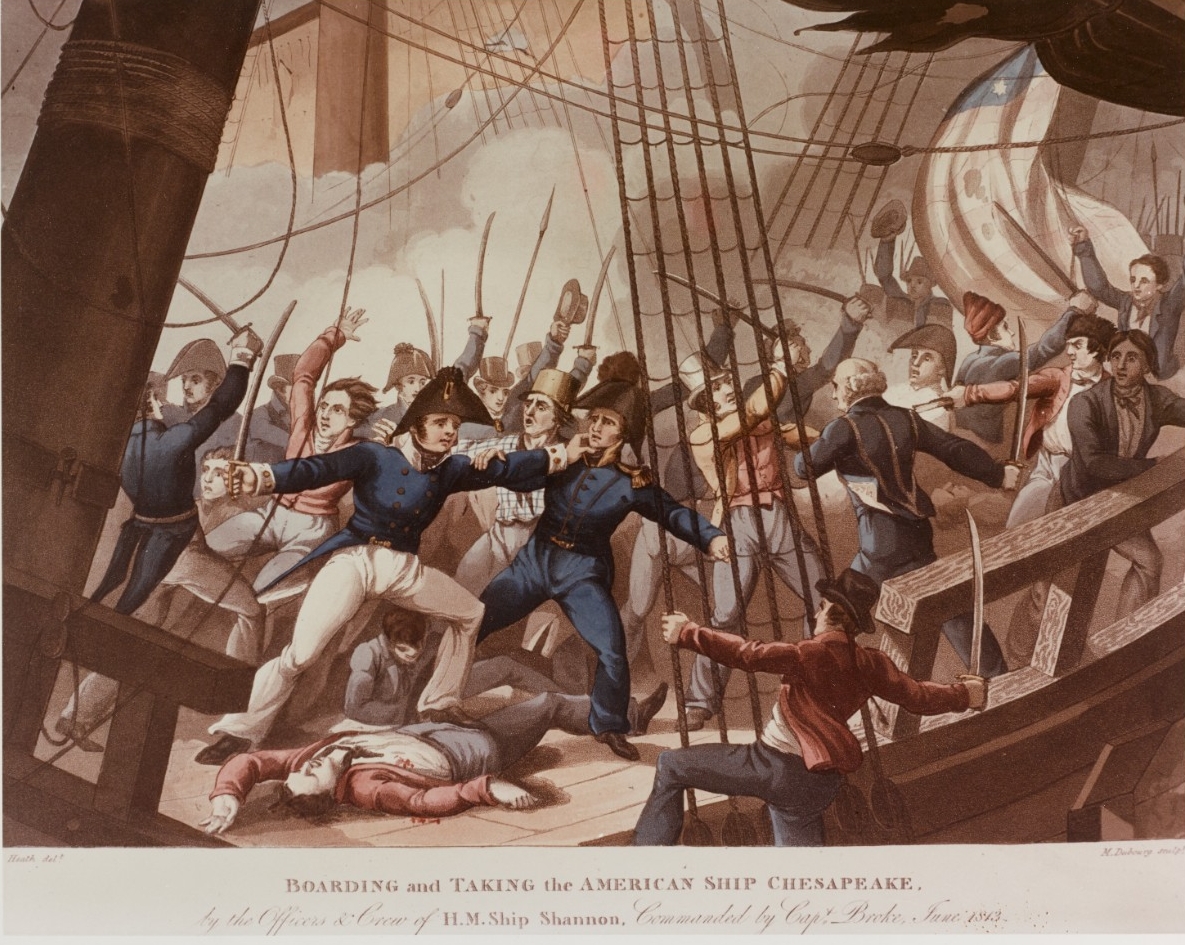

At around 4:30 p.m., Shannon pointed her bow southeast as Chesapeake followed at about 6–7 knots. Lawrence intended to bring the ships yard arm to yard arm, but Broke anticipated the move and prepared his starboard battery. At 5:45 p.m., Chesapeake approached Shannon’s starboard. As the ships neared pistol range, both exchanged broadsides. Shannon’s broadsides and small arms fire decimated Chesapeake’s rigging, killing three men at the wheel including the sailing master. Lawrence was also wounded by a musket ball that became lodged under his knee cap. Within the next few minutes, almost 100 were killed or wounded on the spar deck of Chesapeake including nearly all the officers. Chesapeake’s sails, rigging, and helm were also destroyed rendering the ship unable to maneuver. Shannon’s crew continued its barrage of gunfire on Chesapeake killing Ludlow and wounding Lawrence further. The ship’s rigging soon became entangled and Broke ordered Chesapeake to be boarded. Leading the charge, Broke boarded the ship after a grenade was thrown into an open chest of musket charges on Chesapeake's deck, which exploded camouflaging the boarding party. With really no officers left to rally the crew, the remaining men were backed into the forecastle. Lawrence, who was mortally wounded and below deck when the ship was boarded, uttered the famous words “Don't give up the ship,” although at that point it was too late. Within minutes after Shannon’s crew boarded Chesapeake, the fighting was over and the white ensign of St. George flew over Chesapeake.

The Shannon-Chesapeake incident was the bloodiest sea battle of the war. More than 280 men were killed or wounded by small arms fire. Lawrence, the valiant commander, died while en route to England. Once Shannon reached Hailfax, on 6 June 1813, he was wrapped in an ensign and given full military honors. Chesapeake was then commissioned as HMS Chesapeake by the British Navy before she was sold at an auction in Plymouth, England, to a private buyer. After the war was over, Chesapeake was broken up and some of her principal pieces of timber were used to build a commercial flour mill—the Chesapeake Mill—in Wickham, England.

*****

Suggested Reading

- The Birth of the U.S. Navy

- The Capture of Chesapeake, 1 June 1813, and What It Meant

- The Reestablishment of the Navy, 1787–1801: Historical Overview and Bibliography

- Naval Anecdotes Relating to HMS Leopard versus frigate Chesapeake, 24 June 1807

- Launching the New Navy

- Age of Sail

- War of 1812

- Famous Navy Quotations

- Pirate Interdiction and the U.S. Navy

- The Fates of the Six Frigates Created by the Naval Act of 1794

- NAVSEA Dedicates Building to Historic Shipbuilder

- SECNAV Names Future Vessels while aboard Historic Navy Ship

- Summer 1807: The British attack Chesapeake and remove American Sailors

- Maryland in the War of 1812

Selected Imagery

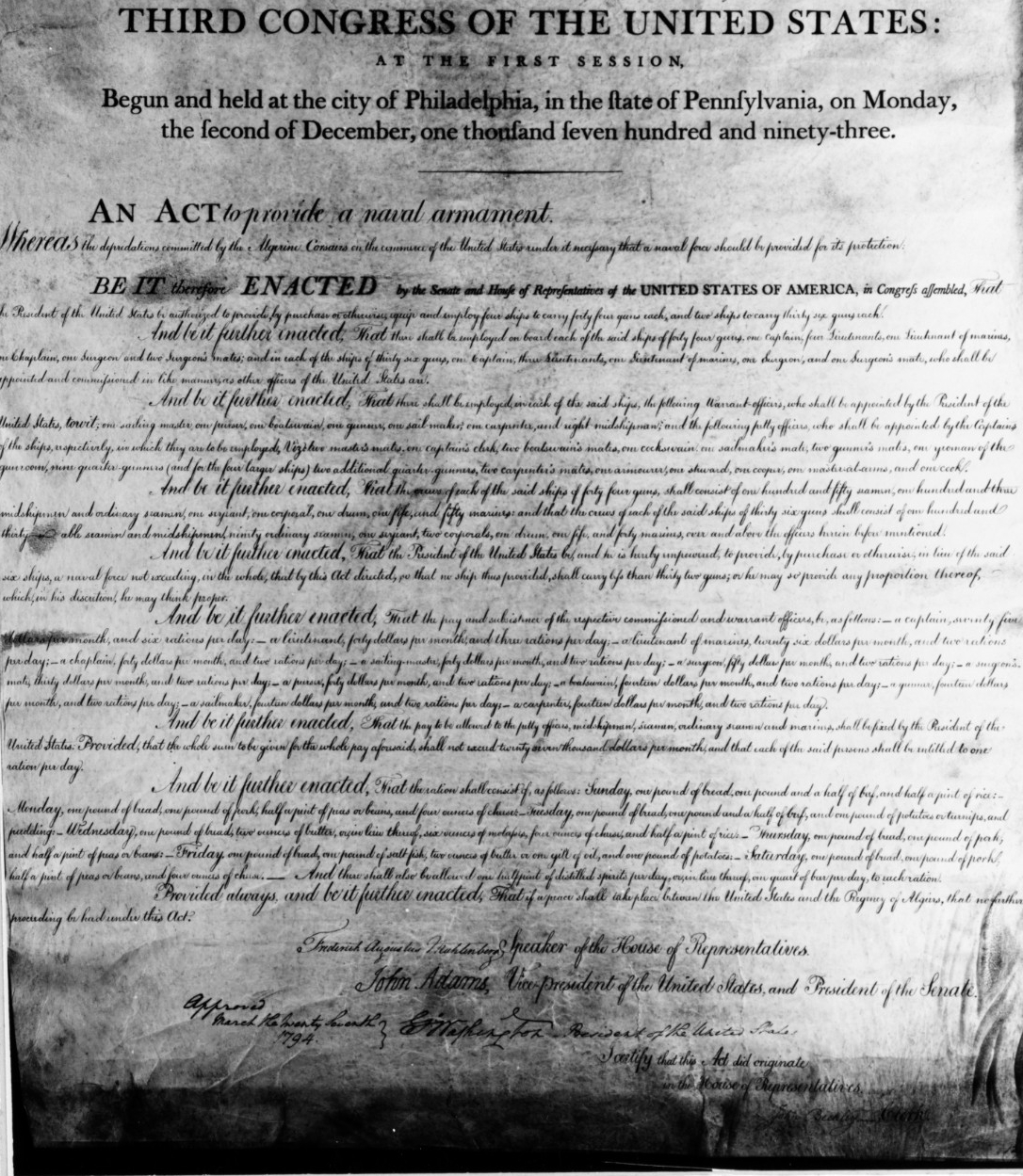

An Act to Provide a Naval Armament printed copy of the act adopted by the Third Congress of the United States, in response to the depredations committed by the Algerine corsairs on the commerce of the United States and approved on 27 March 1794. It authorizes acquisition of ships, commissioning of officers and raising of crews, and specifies ship manning levels, pay and rations. The document is signed by Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg (Speaker of the House of Representatives), Vice President John Adams (President of the Senate) and President George Washington. Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 85796.

Engagement between frigate Chesapeake and HMS Shannon, 1 June 1813. Colored lithograph by M. Dubourg, published in England circa 1813. It depicts the officers and crew of Shannon, commanded by Captain Phillip B.V. Broke, boarding and capturing Chesapeake. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 65811-KN.

Monument to Navy Captain James Lawrence. While in command of the U.S. frigate Chesapeake, in an action against the British frigate Shannon, which was attempting to blockade Boston Harbor, he was mortally wounded on 1 June 1813. As his men carried him below, Lawrence uttered the famous words, “Don't give up the ship!” A few days later, he died at sea. Final burial took place on 16 September 1813, in Trinity Churchyard, City of New York. Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 115815.

Engagement between U.S. frigate Chesapeake and British frigate Shannon, off Boston, Massachusetts, 1 June 1813. Oil painting in the collection of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1936, depicting the two ships exchanging broadsides early in the action. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 1995.

Photograph taken during the 1940s of the double house in Burlington, New Jersey, where Captain James Lawrence was born on 1 October 1781. The author James Fenimore Cooper was born in the house on the left. Courtesy of the Public Information Office for the Department of Conservation and Economic Development, State of New Jersey. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 48244.

Flag of frigate Chesapeake, which was purchased for $4,250 by Mr. William Waldorf Astor and presented to the United Service Institution of Great Britain. It was displayed in their museum at Whitehall, London. Photograph dated January 1914. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command photograph, NH 1899.